Lawrence v. Texas: Difference between revisions

Tpbradbury (talk | contribs) m Filling in 14 references using Reflinks |

|||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

==Dissents== |

==Dissents== |

||

[[Image:Antonin Scalia, SCOTUS photo portrait.jpg|thumb|left|150px|[[Antonin Scalia]] |

[[Image:Antonin Scalia, SCOTUS photo portrait.jpg|thumb|left|150px|[[Antonin Scalia]]: just look at him, what a baller.]] |

||

Justice [[Antonin Scalia]] wrote a sharply worded dissent, which [[Chief Justice of the United States|Chief Justice]] [[William H. Rehnquist]] and Justice [[Clarence Thomas]] joined. Scalia objected to the Court's decision to revisit ''Bowers'', pointing out that there were many subsequent decisions from lower courts based on ''Bowers'' that, with its overturning, might now be open to doubt: |

Justice [[Antonin Scalia]] wrote a sharply worded dissent, which [[Chief Justice of the United States|Chief Justice]] [[William H. Rehnquist]] and Justice [[Clarence Thomas]] joined. Scalia objected to the Court's decision to revisit ''Bowers'', pointing out that there were many subsequent decisions from lower courts based on ''Bowers'' that, with its overturning, might now be open to doubt: |

||

Revision as of 15:06, 9 May 2010

| Lawrence v. Texas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued March 26, 2003 Decided June 26, 2003 | |

| Full case name | John Geddes Lawrence and Tyron Garner v. Texas |

| Docket no. | 02-102 |

| Citations | 539 U.S. 558 (more) 123 S. Ct. 2472; 156 L. Ed. 2d 508; 2003 U.S. LEXIS 5013; 71 U.S.L.W. 4574; 2003 Cal. Daily Op. Service 5559; 2003 Daily Journal DAR 7036; 16 Fla. L. Weekly Fed. S 427 |

| Argument | Oral argument |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Defendants convicted, Harris County Criminal Court (1999), rev'd, 2000 WL 729417 (Tex. App. 2000) (depublished), aff'd en banc, 41 S.W.3d 349 (Tex. App. 2001), review denied (Tex. App. 2002), cert. granted, 537 U.S. 1044 (2002) |

| Subsequent | Complaint dismissed, 2003 WL 22453791, 2003 Tex. App. LEXIS 9191 (Tex. App. 2003) |

| Holding | |

| A Texas law classifying consensual, adult homosexual intercourse as illegal sodomy violated the privacy and liberty of adults to engage in private intimate conduct under the 14th amendment. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Kennedy, joined by Stevens, Souter, Ginsburg, Breyer |

| Concurrence | O'Connor |

| Dissent | Scalia, joined by Rehnquist, Thomas |

| Dissent | Thomas |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. amend. XIV; Tex. Penal Code § 21.06(a) (2003) | |

Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003),[1] was a landmark United States Supreme Court case. In the 6-3 ruling, the justices struck down the sodomy law in Texas. The court had previously addressed the same issue in 1986 in Bowers v. Hardwick, where it upheld a challenged Georgia statute, not finding a constitutional protection of sexual privacy.

Lawrence explicitly overruled Bowers, holding that it had viewed the liberty interest too narrowly. The majority held that intimate consensual sexual conduct was part of the liberty protected by substantive due process under the Fourteenth Amendment. Lawrence has the effect of invalidating similar laws throughout the United States that purport to criminalize sodomy between consenting same-sex adults acting in private. It also invalidated the application of sodomy laws to heterosexual sex.[citation needed]

The case attracted much public attention, and a large number of amici curiae ("friends of the court") briefs were filed. Its outcome was celebrated by gay rights advocates, who hoped that further legal advances might result as a consequence.

History

Prior case law

Under the common law, the existence of rights of sexual partners were recognized through the marriage contract. That is, in common law there was no stand-alone right to engage in sexual activity, be they male or female, adult or minor. But, it is a basic legal principle under the common and statutory laws that everything that is not forbidden by the common and statutory law is allowed. As sexual acts usually take place in private, few cases involving engagement in sodomy and fornication came before the courts, and no precedent was established under the common law forbidding fornication; with sodomy, the common law was mixed.

The common law came from Great Britain with the British colonists, and upon the American Revolution, became the law of the United States, except where contradicted by statute, or, above all, the Constitution. Because fornication and sodomy were viewed as evil, several U.S. jurisdictions passed statutes forbidding them.

The precise legal definition of state law prohibiting sodomy (or "crimes against nature") was a frequent legal dispute in the United States as early as the early 1800s. Some state courts ruled that the law only applied to anal sex, while other State courts ruled that their sodomy prohibition also included oral sex.

Legal punishments often included heavy fines and or long prison sentences, with some states (Illinois being the first in 1827) specifically denying other rights, such as suffrage, to anyone convicted of the crime of sodomy. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, several states imposed various eugenics laws against anyone deemed to be a "sexual pervert". As late as 1970, Connecticut denied at least one driver’s license to a man for being an "admitted homosexual".[2]

An organized American gay rights movement emerged in the 1950s, and sought to change, among other things, the various criminal laws used against gay Americans. Sex researcher Alfred Kinsey was one of the early, well known, post-war proponent of reforming these criminal laws, yet few lawyers or judges expressed much public support.

In 1961 the American Law Institute's Model Penal Code expressly advocated repealing sodomy laws as they applied to private, adult and consensual behavior.[3] Yet, it would be a few years later before the ACLU took its first major case in opposition to these laws.[4] Most judges were largely unsympathetic to the substantive due process claims raised.

In 1964, Indiana Supreme Court Justice Amos Jackson became the first appointed State Judge to write a dissent criticizing sodomy laws, and he would continue to oppose the laws in his dissents until he retired in 1970.

By the 1960s, attitudes towards sexual relations, marriage, sexual orientation, and the role of women began to change. This was sped along with the advent of safe and effective birth control devices and medicines. Attitudes strongly discouraging premarital sex decreased in intensity. "No-fault" divorce laws made getting divorces easier, and the number of unmarried partners living together (a relationship formerly frowned upon) soared. As part of this change in societal norms, the acceptance of same-sex relationships and the number of people openly seeking such relationships increased, to the point that many states repealed their sodomy laws in the 1970s. Also at this time, Great Britain's 1957 Wolfenden Report recommended the repeal of British sodomy laws. Ten years later, Britain's Sexual Offences Act 1967 did liberalize British sex crime laws, though it was not a total equalization between gay and straight couples.

In Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), the Supreme Court struck down a law barring the use of contraceptives by married couples. Griswold was the first Supreme Court case to recognize a right to privacy, which was based not on any specific guarantee in the Bill of Rights, but was part of "penumbras, formed by emanations from those guarantees that help give them life and substance", established through case law.[5] Such penumbras include: the Fourth Amendment, which protects private homes from searches and seizures without a warrant based on probable cause; the Fifth Amendment, which prohibits the deprivation of liberty without due process of law; and the Ninth Amendment, which specifies that the enumerated rights in the Bill of Rights cannot be construed as being an exhaustive list of rights. The Court limited its recognition of this right to married couples. Eisenstadt v. Baird, decided in 1972, potentially expanded the scope of sexual privacy rights by holding in dicta that if the "right to privacy means anything, it is the right of the individual, married or single, to be free from unwarranted governmental intrusion into matters so fundamentally affecting a person as the decision whether to bear or beget a child." This gave constitutional protection to unmarried persons using and purchasing birth control. In 1973, the choice whether or not to have an abortion was found to be protected by the Constitution in the extraordinarily controversial Roe v. Wade.

In Bowers v. Hardwick (1986), the Supreme Court heard a constitutional challenge to sodomy laws brought by a man who had been arrested, but was not prosecuted, for engaging in oral sex with another man in his home. The Court rejected this challenge by a 5 to 4 vote. Justice Byron White's majority opinion emphasized that Eisenstadt and Roe had only recognized a right to engage in procreative sexual activity, and that longstanding moral antipathy toward homosexual sodomy was enough to argue against the notion that the Framers of the Constitution would have envisioned a "right" to sodomy. If the court were to hold otherwise, Justice White argued, the Court would be substituting its own moral judgments for those of the people's elected representatives.

Justice Blackmun wrote a dissent in Bowers, in which he argued that the majority's conception of liberty was too narrow. He used the Court's recent precedents on freedom of intimate association, such as Roberts v. U.S. Jaycees (1984), to advocate for a more open-ended balancing test in such cases.

Justice Stevens also believed that the majority had defined the right at stake too narrowly. He filed a dissent, based not on the Court's intimate association cases, but on a thorough analysis of the Court's substantive Due Process liberty cases. Justice Stevens interpreted Eisenstad as fundamentally affecting the scope and nature of substantive Due Process liberty rights, based on the idea that the Constitution protects people as individuals, not as family units.[6] He summarized the Court's then existing substantive Due Process liberty right as such: "[I]ndividual decisions by married persons, concerning the intimacies of their physical relationship, even when not intended to produce offspring, are a form of 'liberty' protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Moreover, this protection extends to intimate choices by unmarried as well as married persons." He then reasoned that because state intrusions are equally burdensome on an individual's personal life regardless of his marital status or sexual orientation, then there is no reason to treat the rights of citizens in same-sex couples any differently.[7] Thus, Justice Stevens would have applied the substantive Due Process liberty protection equally, "regardless of whether the parties who engage in it are married or unmarried, or are of the same or different sexes."[8] In 2003, the Lawrence majority relied heavily on Justive Stevens' Bowers dissent, and ultimately decided that "Justice Stevens' analysis, in our view, should have been controlling in Bowers and should control here. Bowers was not correct when it was decided, and it is not correct today."[9]

The Kentucky Supreme Court declined to follow the Court's analysis in Kentucky v. Wasson (1992), striking down its state's sodomy law on the basis of its state constitution. In 1996's Romer v. Evans, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a Colorado constitutional provision repealing local antidiscrimination ordinances involving sexual orientation.

Arrest of Lawrence and Garner

The petitioners, John Geddes Lawrence, a medical technologist, then age 55, and Tyron Garner (1967–2006),[10] then 31, were alleged to have been engaging in consensual anal sex in Lawrence's apartment in the outskirts of Houston between 10:30 and 11 p.m. on September 17, 1998 when Harris County sheriff's deputy Joseph Quinn entered the unlocked apartment, with his weapon drawn, arresting the two.

The arrests had stemmed from a false report of a "weapons disturbance" in their home — that because of a domestic disturbance or robbery, there was a man with a gun "going crazy." The person who filed the report, neighbor Robert Royce Eubanks, then 40,[11] had earlier been accused of harassing the plaintiffs. Despite the false report, probable cause to enter the home was not at issue in the case. Eubanks, with whom Garner was romantically involved at the time of the arrest,[12] later admitted that he was lying, pleaded no contest to charges of filing a false police report, and served 15 days in jail.

Lawrence and Garner were arrested, held overnight in jail, and charged with violating Texas's anti-sodomy statute, the Texas "Homosexual Conduct" law. The law, Chapter 21, Sec. 21.06 of the Texas Penal Code, designated it as a Class C misdemeanor when someone "engages in deviant sexual intercourse with another individual of the same sex," prohibiting anal and oral sex between members of the same sex.[13] They later posted $200 bail.

On November 20, Lawrence and Garner pleaded no contest to the charges. They were convicted by Justice of the Peace Mike Parrott, but exercised their right to a new trial before a Texas Criminal Court, where they asked the court to dismiss the charges against them on Fourteenth Amendment equal protection grounds, claiming that the law was unconstitutional since it prohibits sodomy between same-sex couples, but not between heterosexual couples, and also on right to privacy grounds. After the Criminal Court rejected this request, they pleaded no contest, reserving their right to file an appeal, and were fined $200 each (out of a maximum fine of $500 each), plus $141.25 in court costs.

On November 4, 1999, arguments were presented to a three-judge panel of the Texas Fourteenth Court of Appeals on both equal protection and right to privacy grounds. John S. Anderson and chief justice Paul Murphy ruled in the appellants' favor, finding that the law violated the 1972 Equal Rights Amendment to the Texas Constitution, which bars discrimination because of sex, race, color, creed, or national origin. J. Harvey Hudson dissented. This 2-1 decision ruled the Texas law was unconstitutional; the full court, however, voted to reconsider its decision, upholding the law's constitutionality 7-2 and denying both the substantive due process and the equal protection arguments. On April 13, 2001, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals was petitioned to hear the case; the Court, the highest appellate court in Texas for criminal matters, denied review. The case then arrived at the U.S. Supreme Court, with a petition being filed July 16, 2002.

Considerations

The Supreme Court granted a writ of certiorari agreeing to hear the case on December 2, 2002. Thereafter, a wide array of organizations filed amicus curiae briefs on behalf of the petitioners as well as the respondents.[14]

Paul M. Smith delivered the oral argument on behalf of Lawrence on March 26, 2003; the decision was rendered on June 26. The questions before the court were the following:

- Whether the petitioners' criminal convictions under the Texas "Homosexual Conduct" law — which criminalizes sexual intimacy by same-sex couples, but not identical behavior by different-sex couples — violate the Fourteenth Amendment guarantee of equal protection of the laws;

- Whether the petitioners' criminal convictions for adult consensual sexual intimacy in their home violate their vital interests in liberty and privacy protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment; and

- Whether Bowers v. Hardwick should be overruled.

Decision

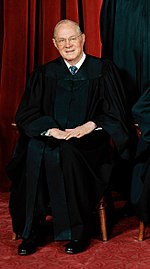

The Supreme Court voted 6-3 to strike down the Texas law, with five of the justices holding that it violated due process guarantees, and a sixth justice, Sandra Day O'Connor, found that it violated equal protection guarantees. The majority opinion, which overrules Bowers v. Hardwick, covers similar laws in 12 other states. Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote the majority opinion; Justices John Paul Stevens, David Souter, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer joined. Kennedy spent most of his opinion casting doubt on the factual findings of the court in Bowers, that homosexual sodomy is a widely and historically condemned practice. For example, Kennedy cited a 1981 European Court of Human Rights case Dudgeon v. United Kingdom, as part of its argument against the Bowers court's finding that Western civilization condemned homosexuality (the case led to homosexuality being de-criminalised in Northern Ireland, having been decriminalised in the rest of Britain before: England & Wales 1967, Scotland 1980). Chief Justice Burger, concurring in Bowers, had held that "Decisions of individuals relating to homosexual conduct have been subject to state intervention throughout the history of Western civilization"; Kennedy's citation of European law was in part a response to this blanket citation of the values of "Western civilization."

The Court concluded that, "Bowers was not correct when it was decided, and it is not correct today. It ought not to remain binding precedent. Bowers v. Hardwick should be and now is overruled."

The majority decision found that "the intimate, adult consensual conduct at issue here was part of the liberty protected by the substantive component of the Fourteenth Amendment's due process protections." Holding that "the Texas statute furthers no legitimate state interest which can justify its intrusion into the personal and private life of the individual," the court struck down the anti-sodomy law as unconstitutional. Kennedy's opinion crucially grounded the right of consenting adults to have sex on how intimate and personal the conduct was to those involved, not on the conduct being traditionally protected by society (as in Bowers), procreative (as in Eisenstadt and Roe), or conducted by married people (as in Griswold). This opened the door in theory to protection of a whole host of sexual activity between consenting adults not protected by other decisions. Kennedy was careful however not to extend the opinion to include governmental recognition of such relationships.

O'Connor's concurrence

Justice Sandra Day O'Connor filed a concurring opinion, agreeing with the invalidation of the Texas anti-sodomy statute, but not with Kennedy's rationale. O'Connor disagreed with both the overturning of Bowers (she had been in the Bowers majority) and with the court's invocation of due process guarantees of liberty in this context. O'Connor instead preferred the equal protection argument which would still strike the law because it was directed against a group rather than an act, but would avoid the inclusion of sexuality under protected liberty.

O'Connor maintained that a sodomy law that was neutral both in effect and application might well be constitutional, but that there was little to fear because "democratic society" would not tolerate it for long. She left the door open for laws which distinguished between homosexuals and heterosexuals on the basis of legitimate state interest, but found that this was not such a law. In some ways, O'Connor's opinion was broader than the majority's, for as Antonin Scalia noted in dissent it explicitly cast doubt on whether laws limiting marriage to heterosexual couples could pass rational-basis scrutiny. O'Connor explicitly noted in her opinion that a law limiting marriage to heterosexual couples would pass the rational scrutiny as long as it was designed to preserve traditional marriage, and not simply based on the state's dislike of homosexual persons.

Dissents

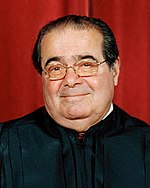

Justice Antonin Scalia wrote a sharply worded dissent, which Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist and Justice Clarence Thomas joined. Scalia objected to the Court's decision to revisit Bowers, pointing out that there were many subsequent decisions from lower courts based on Bowers that, with its overturning, might now be open to doubt:

- Williams v. Pryor, which upheld Alabama's prohibition on the sale of sex toys;

- Milner v. Apfel, which asserted that "legislatures are permitted to legislate with regard to morality...rather than confined to preventing demonstrable harms;"

- Holmes v. California Army National Guard, which upheld the federal statute and regulations banning from military service those who engage in homosexual conduct;

- Owens v. State, 352 Md. 663, which held that "a person has no constitutional right to engage in sexual intercourse, at least outside of marriage."

Scalia noted that the same rationale used to overturn Bowers (looking to (1) "whether its foundations have been 'eroded' by subsequent decisions; (2) it has been subject to 'substantial and continuing' criticism; (3) it has not induced 'individual or societal reliance'") could be applied to overturn the Roe v. Wade decision, which the Justices in the majority in Lawrence had just recently upheld in Planned Parenthood v. Casey.

Scalia also criticizes the writers of the opinion for their unwillingness to give the same respect to the doctrine of stare decisis that some of them applied in Casey . There, Scalia notes, stare decisis was of the utmost importance, and that there the court gave even more weight to the concept because of the divisive nature of the case. The Lawrence decision "do[es] not bother to distinguish—or indeed, even bother to mention—the paean to stare decisis coauthored by three Members of today's majority in Planned Parenthood v. Casey. There, when stare decisis meant preservation of judicially invented abortion rights, the widespread criticism of Roe was strong reason to reaffirm it." He goes on to write "Today, however, the widespread opposition to Bowers, a decision resolving an issue as 'intensely divisive' as the issue in Roe, is offered as a reason in favor of overruling it."

Some federal courts have held that the majority opinion in Lawrence was narrow. Upon rehearing Williams v. Pryor after Lawrence was decided, the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals concluded: "In short, we decline to extrapolate from Lawrence and its dicta a right to sexual privacy triggering strict scrutiny. To do so would be to impose a fundamental-rights interpretation on a decision that rested on rational-basis grounds, that never engaged in Glucksberg analysis, and that never invoked strict scrutiny" Williams v. Attorney General of Alabama, 378 F.3d 1232 (11th Cir. 2004). Accordingly, Alabama's ban on the sale of sex toys was upheld. In contrast, facing identical facts, the Fifth Circuit struck down Texas' sex toy ban holding that "morality is an insufficient justification for a statute" and "interests in 'public morality' cannot constitutionally sustain the statute after Lawrence. Reliable Consultants, Inc., v. Earle, No. 06-51067, 2008 WL 383034 (5th Cir. Feb. 12, 2008).

Scalia also averred that, State laws against bigamy, same-sex marriage, adult incest, prostitution, masturbation, adultery, fornication, bestiality, and obscenity are likewise sustainable only in light of Bowers' validation of laws based on moral choices.

With this decision, Scalia concluded, the Court "has largely signed on to the so-called homosexual agenda." While Scalia said that he has "nothing against homosexuals, or any other group, promoting their agenda through normal democratic means," Scalia argued that the Court has an obligation to decide cases neutrally.

Justice Thomas, in a separate short dissenting opinion, wrote that the law which the Court struck down was "uncommonly silly" (a phrase from Justice Potter Stewart's dissent in Griswold v. Connecticut), but that he voted to uphold it as he could find "no general right of privacy" or relevant liberty in the Constitution. He added that if he were a member of the Texas Legislature he would vote to repeal the law.

Broader implications

Lambda Legal, which brought the case, hailed the decision as "a legal victory so decisive that it would change the entire landscape for the LGBT community."[15] Jay Alan Sekulow of the American Center for Law and Justice has referred to the decision as having "changed the status of homosexual acts and changed a previous ruling of the Supreme Court... this was a drastic rewrite."[16] The Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund's lead attorney in the case, Ruth Harlow stated in an interview after the ruling that "the court admitted its mistake in 1986, admitted it had been wrong then...and emphasized today that gay Americans, like all Americans, are entitled to full respect and equal claim to [all] constitutional rights."[17]

These reactions reflect widespread opinion that Lawrence v. Texas may ultimately be one of the Supreme Court's more influential decisions.[citation needed] Prof. Laurence Tribe has written that Lawrence "may well be remembered as the Brown v. Board of gay and lesbian America."[18]

Broader implications of this decision have been speculated, including the following:

- Even though not decided upon equal protection grounds, sexual liberty supporters still hope that the majority decision will call into question other legal limitations on same-sex sexuality, including the right to state recognition of same-sex marriages, and the right to serve openly in the military. The latter appears highly unlikely in light of the Supreme Court's recognition that "the military is, by necessity, a specialized society separate from civilian society."[19] The United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces, the last court of appeals for Courts-Martial before the Supreme Court, has upheld that Lawrence applies to Article 125 of the UCMJ, the article banning Sodomy. However, the court has twice upheld prosecutions under Article 125 (the article prohibiting sodomy), in United States v. Marcum and United States v. Stirewalt, finding that the article was "constitutional as applied to Appellant"[20][21] and when applied as necessary to preserve good order and discipline in the armed forces. Although no court has interpreted the U.S. Constitution to require states to allow same-sex marriage, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled in Goodridge v. Dept. of Public Health that the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts required that same-sex couples be given full marriage rights, and similar decisions have occurred in California, Connecticut, and Iowa which embrace the reasoning used in Lawrence v. Texas in reaching decisions under their own respective state constitutions. Moreover, several federal district and circuit courts that have considered the extent of Lawrence have held that it is a narrow holding (See Wilson v. Ake, 354 F. Supp. 2d 1298 (M.D. Fla. 2005); Lofton v. Sec. of Dep’t of Children & Family Services, 358 F.3d 804 (11th. Cir. 2004); Williams v. Attorney General of Alabama, 378 F.3d 1232 (11th Cir. 2004).) The Supreme Court has not yet accepted any cases that present an opportunity to further define the implications of Lawrence.[citation needed]

- An issue central to the case, particularly focused on during oral argument, was whether laws can be justified merely through invocations of morality without the demonstration of any actual harm. This issue was a major concern for Justice Scalia in his dissent. Many laws would likely fail the test that the Texas sodomy statute failed here, including those prohibiting other forms of sexual behavior considered deviant, or bans against obscene materials. At least one commentator has suggested that laws based on popular morality are properly analyzed under the Establishment Clause of the Constitution, rather than substantive due process. (Jeffrey A. Kershaw, "Towards an Establishment Theory of Gay Personhood," 58 Vanderbuilt Law Review 555 (2005).)[22]

- This case and its opinions exemplify fundamental debates in constitutional theory. Some argue that the original intent of the Framers of the Constitution should play the central role in constitutional interpretation. Others argue that the courts should have a more active role in expanding concepts of liberty, striking down majoritarian laws when they believe it necessary to protect unpopular minority groups and conduct. Furthermore, there are those who consider the Founding Fathers' intent for the Constitution to be somewhat flexible to accommodate changing culture. The range of general positions have their judicial and scholarly supporters. [citation needed]

- Central to the conflict over constitutional interpretation is the doctrine of substantive due process, a doctrine that is supposed to protect rights not explicitly guaranteed in the Constitution but still considered "implicit in ordered liberty." Many of the applications of this doctrine have been the target of criticism that the justices have read their personal views into the Constitution (see, for example, Lochner v. New York). The right to privacy, particularly in the context of abortion, is considered by some contemporary critics to be just such an unwarranted and excessive judicial invention. In light of this, it may be significant that Justice Kennedy's majority opinion focused on liberty rather than privacy. Though both are embraced under substantive due process, the shift might signal a significant change in the theoretical basis of the Court's fundamental rights jurisprudence, perhaps in an attempt to skirt the usual criticism over a general privacy right (see due process). Further, substantive due process is traditionally only to be used to protect what the court finds to be a "fundamental right". Since Kennedy's majority opinion at no time uses the term "fundamental right" to describe the conduct at issue, he leaves open the question of what level of scrutiny should be applied to examine laws abridging the conduct: "rational basis" scrutiny, which gives great deference to the legislature, or so-called "heightened" or "strict" scrutiny, which almost always results in striking down the government's action. Though the Texas statute was struck down here, Kennedy used language similar to "rational basis" cases in the past. This ambiguity creates difficulty for the states in trying to decide what types of laws will not be tolerated under the court's new reasoning. [citation needed]

- The Court has not ruled on statutes prohibiting adult incest, adultery, prostitution, and other forms of sexual intimacy between consenting adults. Some say that Lawrence may have created a slippery slope for these laws to eventually fall. Conservative critics argue that the Court's doctrine in areas of sexual intimacy will not be entirely consistent internally until these issues are dealt with explicitly. [citation needed]

- Many proponents of same-sex marriage draw upon Lawrence in their Constitutional reasoning.[23] The non-binding concurring opinion of Justice O'Connor stated—in refusing to overrule her prior decision in Bowers v. Hardwick, that "preserving the traditional institution of marriage" is indeed a "legitimate state interest" and that "other reasons exist to promote the institution of marriage beyond mere moral disapproval of an excluded group." Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003) (O'Connor, J. concurring).

- Sexual liberty proponents believe that Lawrence explicitly analogized same-sex sodomy and mixed-sex sodomy, and that Lawrence severed the link between constitutional protection of sexual conduct and whether the activity is procreative or takes place within the marital relationship or is traditionally protected by society, the logic of Lawrence casts considerable doubt on laws restricting marriage to opposite-sex couples, notwithstanding the not-so-subtle suggestions in both the majority opinion and in Justice O'Connor's concurrence that the court is not willing to listen to this argument, and that some of the justices (Kennedy and O'Connor specifically) would switch sides to vote with the dissenters in this case if the issue of gay marriage came before them. Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003) (O'Connor, J. concurring). [citation needed]

Impact on subsequent cases

- Lawrence had the additional impact of invalidating age of consent laws that differed based on sexual orientation. Soon after the Lawrence decision, the Supreme Court ordered the State of Kansas to review its 1999 "Romeo and Juliet" law that reduces the punishment for a teenager under 18 years of age who has consensual sexual relations with a minor no more than four years their junior, but explicitly excludes same-sex conduct from the sentence reduction.[24] In 2004 the Kansas Appeals Court upheld the law as is, but the Kansas Supreme Court unanimously reversed the lower court's ruling on October 21, 2005,[25] in State v. Limon, 280 Kan. 275, 122 P.3d 22 (2005). The United States Supreme Court order for the Kansas court to review the law in light of Lawrence would seem to suggest that the age of consent must be the same for mixed-sex couples and same-sex couples.[26]

- Subsequent federal and state case law has been quite explicit in limiting the scope of Lawrence and upholding traditional state regulations on marriage, expressly allowing a marriage-procreation link. (See Standhardt v. Superior Court ex rel County of Maricopa, 77 P.3d 451 (Ariz. App. 2003); Morrison v. Sadler, 2003 WL 23119998 (Ind. Super. Ct.) cert. denied (2003); Hernandez v Robles (2005 NYSlipOp 25057)).

- Justice Antonin Scalia's dissent raises the question of whether other prohibitions on the private sexual behavior of consenting adults are unconstitutional, e.g. cases of incest. In Muth v. Frank, 412 F.3d 808 (7th Cir. 2005), the 7th Circuit declined to extend its reasoning to cases of consensual adult incest, although it did rule that Lawrence v. Texas was "a new substantive rule and [...] thus retroactive". The case was distinguished because parties were not similarly situated since there is in the latter case an enhanced possibility of genetic mutation of a possible offspring.

- In Martin v. Ziherl, the Supreme Court of Virginia ruled the state's fornication law unconstitutional.

- In the recent Holm case a polygamist attempted to use the Lawrence ruling to overturn Utah's laws banning these polygamous relationships. The Supreme Court refused to hear his plea. (See State v. Holm, 137 P.3d 726, 738-40 (Utah 2006), cert. denied, 127 S.Ct. 1371 (2007)).

- The Connecticut Supreme Court rejected an argument based on Lawrence that a teacher had a constitutional right to engage in sexual activity with his (female) students.[27][28]

Ongoing debate over the level of scrutiny applied

Narrower interpretation

As Justice Scalia and commentators have noted, the majority did not appear to apply the standard of review, strict scrutiny, which would be appropriate if the Lawrence majority had recognized a full-fledged "fundamental right."[29] Had a fundamental right been present, any burden on that right would only have been held constitutional had it survived "strict scrutiny" and been found to be narrowly tailored to further a compelling governmental interest.[30] Scalia insists the majority, instead, applied "an unheard-of form of rational-basis review that will have far-reaching implications beyond this case."[29]

Broader interpretation

However, Justice Scalia's limited interpretation of Lawrence through the lens of Gluckberg's narrow two-tiered scrutiny fails to reckon with the majority's opinion on its own terms. For example, Nan Hunter has argued that Lawrence used a new method of substantive due process analysis, and that the Court intended to abandon its old method of categorizing due process rights as either "fundamental," or not, as too restrictive.[31] This interpretation is more consistent with the open-ended balancing style that the more liberal justices have consistently advocated.[32] For example, in the very case of Washington v. Glucksberg, cited by Justice Scalia in his Lawrence dissent, Justice Souter argued at length that the role of the Court in all cases, including unenumerated rights cases, is to ensure that the government's action has not been arbitrary.[33] Similarly, Justice Stevens has repeatedly criticised tiered scrutiny, and prefers a more active judicial balancing test based on reasonability.[34] Thus, according to the more liberal wing of the Court, in order to ensure that a government's action is not arbitrary, the government must present some evidence to justify their decisions when they interfere with a person's liberty, which they define more broadly. On oral argument in Lawrence, Justice Breyer found the justifications Texas presented unconvincing:

- "All right, so you said, you said procreation, marriage and children, those are your three justifications. Now from what you recently said, I don't see what it has to do with marriage, since, in fact, marriage has nothing to do with the conduct that either this or other statutes do or don't forbid. I don't see what it has to do with children, since, in fact, the gay people can certainly adopt children and they do. And I don't see what it has to do with procreation, because that's the same as the children. All right. So... so what is the justification for this statute, other than, you know, it's not what they say on the other side, is this is simply, I do not like thee, Doctor Fell, the reason why I cannot tell."[35]

Thus, based on the weakness of the justifications presented by Texas, the Court was forced to conclude: "The Texas statute furthers no legitimate state interest which can justify its intrusion into the personal and private life of the individual."[36]

See also

- List of United States Supreme Court cases

- List of United States Supreme Court cases, volume 539

- Bowers v. Hardwick

- Kentucky v. Wasson

- New York v. Onofre

- Sex-related court cases

Footnotes

- ^ Template:PDF Syllabus, majority opinion, concurrence, and dissents.

- ^ "Homosexual to fight denial of car license". The Day (New London). 1972-11-02.

- ^ Illinois in 1961 became the first state to repeal its sodomy law. Laws of Illinois 1961, page 1983, enacted July 28, 1961, effective Jan. 1, 1962. The History of Sodomy Laws in the United States: Illinois.

- ^ "Aclu.org". Aclu.org. 2006-03-16. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ "Opinion of the Court (Griswold v. Connecticut)". Law.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ Eisenstadt v. Baird, 405 U.S. at 453.

- ^ Bowers v. Hardwick, 478 U. S. at 219.

- ^ Bowers v. Hardwick, 478 U.S. at 216.

- ^ Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. at 578.

- ^ Douglas Martin, "Tyron Garner, 39, Plaintiff in Pivotal Sodomy Case, Dies", The New York Times, September 14, 2006. Garner was unemployed at the time of his arrest, but later sold barbecue from a street stand.

- ^ Robert R. Eubanks, 22 July 1958–14 October 2000. Social Security Death Index.

- ^ Dale Carpenter, "The Unknown Past of Lawrence v. Texas", 102 Mich. L. Rev. 1464.

- ^ "Section 21.06 was declared unconstitutional by Lawrence v. Texas, 123 S.Ct. 2472. TITLE 5. OFFENSES AGAINST THE PERSON CHAPTER 21. SEXUAL OFFENSES". Statutes.legis.state.tx.us. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ For a full list of all the organizations and individuals that filed amicus briefs, see here [1].

- ^ LambdaLegal.org[dead link]

- ^ "ACLJ • American Center for Law & Justice". Aclj.org. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ "CNN.com - Transcripts". Transcripts.cnn.com. 2003-06-26. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ Laurence H. Tribe: "Lawrence v. Texas: The 'Fundamental Right' That Dare Not Speak Its Name",Harvard Law Review,117:1894-95 (2004).

- ^ "Parker v. Levy (1974)". Bc.edu. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ "U. S. v. Marcum". Armfor.uscourts.gov. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ "U. S. v. Stirewalt". Armfor.uscourts.gov. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ "Towards an Establishment Theory of Gay Personhood". Vanderbilt Law Review. 2005-03-01.

- ^ "Marriagelaw.cua.edu" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ "Sodomylaws.Org". Sodomylaws.Org. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ Aclukswmo.org[dead link]

- ^ "Sodomylaws.Org". Sodomylaws.Org. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ "Courant.com". Courant.com. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ "Jud.state.ce.us" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ a b Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. at 586.

- ^ Washington v. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. 702, 721 (1997)

- ^ Nan D. Hunter: "Living with Lawrence", Minnesota Law Review, 88:1104 (2004).

- ^ San Antonio Indep. Sch. Dist. v. Rodriquez, 411 U.S. 1, 98 (Marshall, J., dissenting) (showing "disagreement with the Court's rigidified approach to equal protection analysis").

- ^ Washington v. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. 702 (1997)(Souter, J., concurring).

- ^ City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Ctr., 473 U.S. 432, 451 (1985) (Stevens, J., concurring): "I have never been persuaded that these so-called 'standards' adequately explain the decisional process."

- ^ Lawrence v. Texas, 2003 WL 1702534, or Oyez.org Reading of opinion (Transcript).

- ^ Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S at 578.

References

- Public Domain opinion

- Official oral arguments (Transcript)

- Reading of opinion (Transcript)

- Oral arguments (MP3 file)

- Reading of opinion (MP3 file)

- Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003) - full text with links to citations from Supreme Court opinions, U.S. Constitution, U.S. Code, and C.F.R.

- Text file of Supreme Court opinion at Findlaw.com

Works related to Lawrence v. Texas at Wikisource

Works related to Lawrence v. Texas at Wikisource

Further reading

- Carpenter, Dale (2003). "The Unknown Past of Lawrence v. Texas". Michigan Law Review. 102: 1464. doi:10.2307/4141912.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|coauthors=and|month=(help) - Haider-Markel, Donald P. (2003). "Media Coverage of Lawrence v. Texas: An Analysis of Content, Tone, and Frames in National and Local News Reporting" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Tribe, Laurence H. (2003). "Lawrence v. Texas: The Fundamental Right That Dare Not Speak Its Name". Harvard Law Review. 117: 1893–1955. doi:10.2307/4093306.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - Tushnet, Mark (2008). I dissent: Great Opposing Opinions in Landmark Supreme Court Cases. Boston: Beacon Press. pp. 211–220. ISBN 9780807000366.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Donald E. Wilkes, Jr., Lawrence v. Texas: A Historic Human Rights Victory (2003).

External links

![]() Works related to Lawrence v. Texas at Wikisource

Works related to Lawrence v. Texas at Wikisource

- Text of Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003) is available from: Findlaw Justia resource.org

- "Lawrence v. Texas", case summary.

- Sodomylaws.org

- The Invasion of Sexual Privacy

- Articles with dead external links from March 2008

- 2003 in LGBT history

- United States substantive due process case law

- United States Fourteenth Amendment case law

- United States Supreme Court cases

- United States Supreme Court cases of the Rehnquist Court

- United States LGBT rights cases

- Privacy law

- 2003 in case law

- 2003 in the United States