Bronze Age

| Bronze Age |

|---|

| ↑ Chalcolithic |

| ↓ Iron Age |

| History of technology |

|---|

The Bronze Age (c. 3300 – c. 1200 BC) was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of the three-age system, following the Stone Age and preceding the Iron Age.[1] Conceived as a global era, the Bronze Age follows the Neolithic, with a transition period between the two known as the Chalcolithic. The final decades of the Bronze Age in the Mediterranean basin are often characterised as a period of widespread societal collapse known as the Late Bronze Age collapse (c. 1200 – c. 1150 BC), although its severity and scope are debated among scholars.

An ancient civilisation is deemed to be part of the Bronze Age if it either produced bronze by smelting its own copper and alloying it with tin, arsenic, or other metals, or traded other items for bronze from producing areas elsewhere. Bronze Age cultures were the first to develop writing. According to archaeological evidence, cultures in Mesopotamia, which used cuneiform script, and Egypt, which used hieroglyphs, developed the earliest practical writing systems. In the Archaeology of the Americas, a five-period system is conventionally used instead, which does not include a Bronze Age, though some cultures there did smelt copper and bronze. Indigenous metalworking arrived in Australia with European contact.

In many areas bronze continued to be rare and expensive, mainly because of difficulties in obtaining enough tin, which occurs in relatively few places, unlike the very common copper. Some societies appear to have gone through much of the Bronze Age using bronze only for weapons or elite art, such as Chinese ritual bronzes, with ordinary farmers largely still using stone tools. However, this is hard to assess as the rarity of bronze meant it was keenly recycled.

Metal use

[edit]Bronze Age civilisations gained a technological advantage due to bronze's harder and more durable properties than other metals available at the time. While terrestrial iron is naturally abundant, the higher temperature required for smelting, 1,250 °C (2,280 °F), in addition to the greater difficulty of working with it, placed it out of reach of common use until the end of the 2nd millennium BC.[citation needed] Tin's lower melting point of 232 °C (450 °F) and copper's moderate melting point of 1,085 °C (1,985 °F) placed both these metals within the capabilities of Neolithic pottery kilns,[citation needed] which date to 6000 BC and were able to produce temperatures of at least 900 °C (1,650 °F).[2]

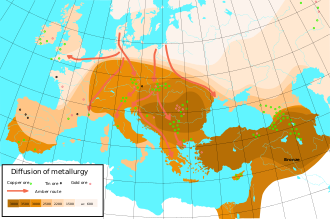

The Bronze Age is characterised by the widespread use of bronze, though the introduction and development of bronze technology were not universally synchronous. Bronze was independently discovered in the Maykop culture of the North Caucasus as early as the mid-4th millennium BC, which makes them the producers of the oldest-known bronze. However, the Maykop culture only had arsenical bronze. Other regions developed bronze and its associated technology at different periods. Tin bronze technology requires systematic techniques: tin must be mined (mainly as the tin ore cassiterite) and smelted separately, then added to hot copper to make bronze alloy. The Bronze Age was a time of extensive use of metals and the development of trade networks.

A 2013 report suggests that the earliest tin-alloy bronze was a foil dated to the mid-5th millennium BC from a Vinča culture site in Pločnik, Serbia, although this culture is not conventionally considered part of the Bronze Age;[3] however, the dating of the foil has been disputed.[4][5]

Near East

[edit]West Asia and the Near East were the first regions to enter the Bronze Age, beginning with the rise of the Mesopotamian civilisation of Sumer in the mid-4th millennium BC. Cultures in the ancient Near East practised intensive year-round agriculture; developed writing systems; invented the potter's wheel, created centralised governments (usually in the form of hereditary monarchies), formulated written law codes, developed city-states, nation-states and empires; embarked on advanced architectural projects; and introduced social stratification, economic and civil administration, slavery, and practised organised warfare, medicine, and religion. Societies in the region laid the foundations for astronomy, mathematics, and astrology.

The following dates are approximate.

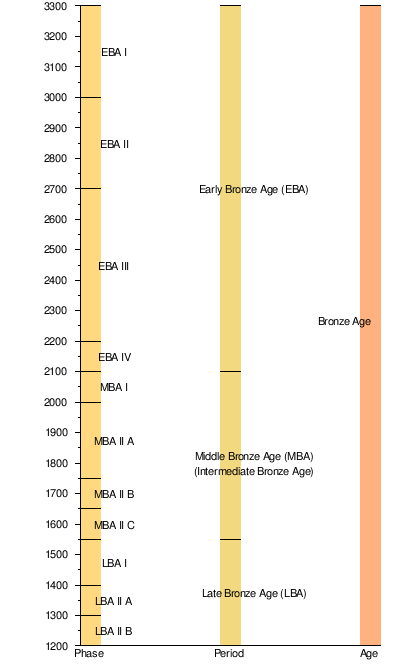

Near East Bronze Age divisions

[edit]The Bronze Age in the Near East can be divided into Early, Middle and Late periods. The dates and phases below apply solely to the Near East, not universally.[6][7][8] However, some archaeologists propose a "high chronology", which extends periods such as the Intermediate Bronze Age by 300 to 500–600 years, based on material analysis of the southern Levant in cities such as Hazor, Jericho, and Beit She'an.[9]

- Early Bronze Age (EBA): 3300–2100 BC

- 3300–3000: EBA I

- 3000–2700: EBA II

- 2700–2200: EBA III

- 2200–2100: EBA IV

- Middle Bronze Age (MBA) or Intermediate Bronze Age (IBA): 2100–1550 BC

- 2100–2000: MBA I

- 2000–1750: MBA II A

- 1750–1650: MBA II B

- 1650–1550: MBA II C

- Late Bronze Age (LBA): 1550–1200 BC

- 1550–1400: LBA I

- 1400–1300: LBA II A

- 1300–1200: LBA II B (Late Bronze Age collapse)

Anatolia

[edit]

The Hittite Empire was established during the 18th century BC in Hattusa, northern Anatolia. At its height in the 14th century BC, the Hittite Kingdom encompassed central Anatolia, southwestern Syria as far as Ugarit, and upper Mesopotamia. After 1180 BC, amid general turmoil in the Levant, which is conjectured to have been associated with the sudden arrival of the Sea Peoples,[10][11] the kingdom disintegrated into several independent "Neo-Hittite" city-states, some of which survived into the 8th century BC.

Arzawa, in Western Anatolia, during the second half of the 2nd millennium BC, likely extended along southern Anatolia in a belt from near the Turkish Lakes region to the Aegean coast. Arzawa was the western neighbour of the Middle and New Hittite Kingdoms, at times a rival and, at other times, a vassal.

The Assuwa league was a confederation of states in western Anatolia defeated by the Hittites under the earlier Tudhaliya I c. 1400 BC. Arzawa has been associated with the more obscure Assuwa generally located to its north. It probably bordered it, and may have been an alternative term for it during some periods.

Egypt

[edit]Early Bronze dynasties

[edit]

In Ancient Egypt, the Bronze Age began in the Protodynastic Period c. 3150 BC. The archaic Early Bronze Age of Egypt, known as the Early Dynastic Period of Egypt,[12][13] immediately followed the unification of Lower and Upper Egypt, c. 3100 BC. It is generally taken to include the First and Second dynasties, lasting from the Protodynastic Period until c. 2686 BC, or the beginning of the Old Kingdom. With the First Dynasty, the capital moved from Abydos to Memphis with a unified Egypt ruled by an Egyptian god-king. Abydos remained the major holy land in the south. The hallmarks of ancient Egyptian civilisation, such as art, architecture and religion, took shape in the Early Dynastic Period. Memphis, in the Early Bronze Age, was the largest city of the time. The Old Kingdom of the regional Bronze Age[12] is the name given to the period in the 3rd millennium BC when Egyptian civilisation attained its first continuous peak of complexity and achievement—the first of three "Kingdom" periods which marked the high points of civilisation in the lower Nile Valley (the others being the Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom).

The First Intermediate Period of Egypt,[14] often described as a "dark period" in ancient Egyptian history, spanned about 100 years after the end of the Old Kingdom from about 2181 to 2055 BC. Very little monumental evidence survives from this period, especially from the early part of it. The First Intermediate Period was a dynamic time when the rule of Egypt was roughly divided between two areas: Heracleopolis in Lower Egypt and Thebes in Upper Egypt. These two kingdoms eventually came into conflict, and the Theban kings conquered the north, reunifying Egypt under a single ruler during the second part of the Eleventh Dynasty.

Nubia

[edit]The Bronze Age in Nubia started as early as 2300 BC.[15] Egyptians introduced copper smelting to the Nubian city of Meroë in present-day Sudan c. 2600 BC.[16] A furnace for bronze casting found in Kerma has been dated to 2300–1900 BC.[15]

Middle Bronze dynasties

[edit]The Middle Kingdom of Egypt spanned between 2055 and 1650 BC. During this period, the Osiris funerary cult rose to dominate popular Ancient Egyptian religion. The period comprises two phases: the Eleventh Dynasty, which ruled from Thebes, and the Twelfth[17] and Thirteenth dynasties, centred on el-Lisht. The unified kingdom was previously considered to comprise the Eleventh and Twelfth Dynasties, but historians now consider part of the Thirteenth Dynasty to have belonged to the Middle Kingdom.

During the Second Intermediate Period,[18] Ancient Egypt fell into disarray a second time between the end of the Middle Kingdom and the start of the New Kingdom, best known for the Hyksos, whose reign comprised the Fifteenth and Sixteenth dynasties. The Hyksos first appeared in Egypt during the Eleventh Dynasty, began their climb to power in the Thirteenth Dynasty, and emerged from the Second Intermediate Period in control of Avaris and the Nile Delta. By the Fifteenth Dynasty, they ruled lower Egypt. They were expelled at the end of the Seventeenth Dynasty.

Late Bronze dynasties

[edit]The New Kingdom of Egypt, also referred to as the Egyptian Empire, existed during the 16th–11th centuries BC. The New Kingdom followed the Second Intermediate Period and was succeeded by the Third Intermediate Period. It was Egypt's most prosperous time and marked the peak of Egypt's power. The later New Kingdom, comprising the Nineteenth and Twentieth dynasties (1292–1069 BC), is also known as the Ramesside period, after the eleven pharaohs who took the name of Ramesses.

Iranian plateau

[edit]

Elam was a pre-Iranian ancient civilisation located east of Mesopotamia. In the Middle Bronze Age, Elam consisted of kingdoms on the Iranian plateau, centred in Anshan. From the mid-2nd millennium BC, Elam was centred in Susa in the Khuzestan lowlands. Its culture played a crucial role in both the Gutian Empire and the Iranian Achaemenid dynasty that succeeded it.

The Oxus civilisation[19] was a Bronze Age Central Asian culture dated c. 2300–1700 BC and centred on the upper Amu Darya (a.k.a.). In the Early Bronze Age, the culture of the Kopet Dag oases and Altyndepe developed a proto-urban society. This corresponds to level IV at Namazga-Tepe. Altyndepe was a major centre even then. Pottery was wheel-turned. Grapes were grown. The height of this urban development was reached in the Middle Bronze Age c. 2300 BC, corresponding to level V at Namazga-Depe.[20] This Bronze Age culture is called the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex.

The Kulli culture,[21][22] similar to that of the Indus Valley Civilisation, was located in southern Balochistan (Gedrosia) c. 2500–2000 BC. The economy was agricultural. Dams were found in several places, providing evidence for a highly developed water management system.

Konar Sandal is associated with the hypothesized Jiroft culture, a 3rd-millennium BC culture postulated based on a collection of artefacts confiscated in 2001.

Levant

[edit]

In modern scholarship, the chronology of the Bronze Age Levant is divided into:

- Early Syrian, or Proto Syrian – corresponding to the Early Bronze Age

- Old Syrian – corresponding to the Middle Bronze Age

- Middle Syrian – corresponding to the Late Bronze Age

The term Neo-Syria is used to designate the early Iron Age.[23]

The old Syrian period was dominated by the Eblaite first kingdom, Nagar and the Mariote second kingdom. The Akkadians conquered large areas of the Levant and were followed by the Amorite kingdoms, c. 2000–1600 BC, which arose in Mari, Yamhad, Qatna, and Assyria.[24] From the 15th century BC onward, the term Amurru is usually applied to the region extending north of Canaan as far as Kadesh on the Orontes River.

The earliest-known contact of Ugarit with Egypt (and the first exact dating of Ugaritic civilisation) comes from a carnelian bead identified with the Middle Kingdom pharaoh Senusret I, whose reign is dated to 1971–1926 BC. A stela and a statuette of the Egyptian pharaohs Senusret III and Amenemhet III have also been found. However, it is unclear when they first arrived at Ugarit. In the Amarna letters, messages from Ugarit c. 1350 BC written by Ammittamru I, Niqmaddu II, and his queen have been discovered. From the 16th to the 13th century BC, Ugarit remained in constant contact with Egypt and Cyprus (Alashiya).

Mitanni was a loosely organised state in northern Syria and south-east Anatolia, emerging c. 1500–1300 BC. Founded by an Indo-Aryan ruling class that governed a predominantly Hurrian population, Mitanni came to be a regional power after the Hittite destruction of Kassite Babylon created a power vacuum in Mesopotamia. At its beginning, Mitanni's major rival was Egypt under the Thutmosids. However, with the ascent of the Hittite empire, Mitanni and Egypt allied to protect their mutual interests from the threat of Hittite domination. At the height of its power during the 14th century BC, Mitanni had outposts centred on its capital, Washukanni, which archaeologists have located on the headwaters of the Khabur River. Eventually, Mitanni succumbed to the Hittites and later Assyrian attacks, eventually being reduced to a province of the Middle Assyrian Empire.

The Israelites were an ancient Semitic-speaking people of the Ancient Near East who inhabited part of Canaan during the tribal and monarchic periods (15th–6th centuries BC),[25][26][27][28][29] and lived in the region in smaller numbers after the fall of the monarchy. The name "Israel" first appears c. 1209 BC, at the end of the Late Bronze Age and the very beginning of the Iron Age, on the Merneptah Stele raised by the Egyptian pharaoh Merneptah.

The Arameans were a Northwest Semitic semi-nomadic pastoral people who originated in what is now modern Syria (Biblical Aram) during the Late Bronze and early Iron Age. Large groups migrated to Mesopotamia, where they intermingled with the native Akkadian (Assyrian and Babylonian) population. The Aramaeans never had a unified empire; they were divided into independent kingdoms all across the Near East. After the Bronze Age collapse, their political influence was confined to Syro-Hittite states, which were entirely absorbed into the Neo-Assyrian Empire by the 8th century BC.

Mesopotamia

[edit]The Mesopotamian Bronze Age began c. 3500 BC and ended with the Kassite period c. 1500 – c. 1155 BC). The usual tripartite division into an Early, Middle and Late Bronze Age is not used in the context of Mesopotamia. Instead, a division primarily based on art and historical characteristics is more common.

The cities of the Ancient Near East housed several tens of thousands of people. Ur, Kish, Isin, Larsa, and Nippur in the Middle Bronze Age and Babylon, Calah, and Assur in the Late Bronze Age similarly had large populations. The Akkadian Empire (2335–2154 BC) became the dominant power in the region. After its fall, the Sumerians enjoyed a renaissance with the Neo-Sumerian Empire. Assyria, along with the Old Assyrian Empire (c. 1800–1600 BC), became a regional power under the Amorite king Shamshi-Adad I. The earliest mention of Babylon (then a small administrative town) appears on a tablet from the reign of Sargon of Akkad in the 23rd century BC. The Amorite dynasty established the city-state of Babylon in the 19th century BC. Over a century later, it briefly took over the other city-states and formed the short-lived First Babylonian Empire during what is also called the Old Babylonian Period.

Akkad, Assyria, and Babylonia used the written East Semitic Akkadian language for official use and as a spoken language. By that time, the Sumerian language was no longer spoken, but was still in religious use in Assyria and Babylonia, and would remain so until the 1st century AD. The Akkadian and Sumerian traditions played a major role in later Assyrian and Babylonian culture. Despite this, Babylonia, unlike the more militarily powerful Assyria, was founded by non-native Amorites and often ruled by other non-indigenous peoples such as the Kassites, Aramaeans and Chaldeans, as well as by its Assyrian neighbours.

Asia

[edit]

Central Asia

[edit]Agropastoralism

[edit]For many decades, scholars made superficial reference to Central Asia as the "pastoral realm" or alternatively, the "nomadic world", in what researchers call the "Central Asian void": a 5,000-year span that was neglected in studies of the origins of agriculture. Foothill regions and glacial melt streams supported Bronze Age agro-pastoralists who developed complex east–west trade routes between Central Asia and China that introduced wheat and barley to China and millet to Central Asia.[30]

Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex

[edit]The Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC), also known as the Oxus civilisation, was a Bronze Age civilisation in Central Asia, dated c. 2400 – c. 1600 BC,[31] located in present-day northern Afghanistan, eastern Turkmenistan, southern Uzbekistan and western Tajikistan, centred on the upper Amu Darya (Oxus River). Its sites were discovered and named by the Soviet archaeologist Viktor Sarianidi (1976). Bactria was the Greek name for the area of Bactra (modern Balkh), in what is now northern Afghanistan, and Margiana was the Greek name for the Persian satrapy of Marguš, the capital of which was Merv in present-day Turkmenistan.

A wealth of information indicates that the BMAC had close international relations with the Indus Valley, the Iranian plateau, and possibly even indirectly with Mesopotamia. All civilisations were familiar with lost wax casting.[32]

According to a 2019 study,[33] the BMAC was not a primary contributor to later South-Asian genetics.

Seima-Turbino phenomenon

[edit]The Altai Mountains, in what is now southern Russia and central Mongolia, have been identified as the point of origin of a cultural enigma termed the Seima-Turbino Phenomenon.[34] It is conjectured that changes in climate in this region c. 2000 BC, and the ensuing ecological, economic, and political changes, triggered a rapid and massive migration westward into northeast Europe, eastward into China, and southward into Vietnam and Thailand[35] across a frontier of some 4,000 mi (6,000 km).[34] This migration took place in just five to six generations and led to peoples from Finland in the west to Thailand in the east employing the same metalworking technology and, in some areas, horse breeding and riding.[34] However, recent genetic testings of sites in south Siberia and Kazakhstan (Andronovo horizon) would rather support spreading of the bronze technology via Indo-European migrations eastwards, as this technology had been well known for quite a while in western regions.[36][37]

It is further conjectured that the same migrations spread the Uralic group of languages across Europe and Asia, with extant members of the family including Hungarian, Finnish and Estonian.[34]

East Asia

[edit]China

[edit]

In China, the earliest bronze artefacts have been found in the Majiayao culture site (3100–2700 BC).[38][39]

The term "Bronze Age" has been transferred to the archaeology of China from that of Western Eurasia, and there is no consensus or universally used convention delimiting the "Bronze Age" in the context of Chinese prehistory.[40] The "Early Bronze Age" in China is sometimes taken to be coterminous with the reign of the Shang dynasty (16th–11th centuries BC),[41] and the Later Bronze Age with the subsequent Zhou dynasty (11th–3rd centuries BC), from the 5th century, called Iron Age China although there is an argument to be made that the Bronze Age never properly ended in China, as there is no recognisable transition to an Iron Age.[42] Together with the jade art that precedes it, bronze was seen as a fine material for ritual art when compared with iron or stone.[43]

Bronze metallurgy in China originated in what is referred to as the Erlitou period, which some historians argue places it within the Shang.[44] Others believe the Erlitou sites belong to the preceding Xia dynasty.[45] The United States National Gallery of Art defines the Chinese Bronze Age as c. 2000 – c. 771 BC, a period that begins with the Erlitou culture and ends abruptly with the disintegration of Western Zhou rule.[46]

There is reason to believe that bronze work developed inside of China apart from outside influence.[47] However, the discovery of the Europoid Tarim mummies in Xinjiang has caused some archaeologists such as Johan Gunnar Andersson, Jan Romgard, and An Zhimin to suggest a possible route of transmission from the West eastwards. According to An Zhimin, "It can be imagined that initially, bronze and iron technology took its rise in West Asia, first influenced the Xinjiang region, and then reached the Yellow River valley, providing external impetus for the rise of the Shang and Zhou civilizations." According to Jan Romgard, "bronze and iron tools seem to have traveled from west to east as well as the use of wheeled wagons and the domestication of the horse." There are also possible links to Seima-Turbino culture, "a transcultural complex across northern Eurasia", the Eurasian steppe, and the Urals.[48] However, the oldest bronze objects found in China so far were discovered at the Majiayao site in Gansu rather than at Xinjiang.[49]

The production of Erlitou represents the earliest large-scale metallurgy industry in the Central Plains of China. The influence of the Saima-Turbino metalworking tradition from the north is supported by a series of recent discoveries in China of many unique perforated spearheads with downward hooks and small loops on the same or opposite side of the socket, which could be associated with the Seima-Turbino visual vocabulary of southern Siberia. The metallurgical centres of northwestern China, especially the Qijia culture in Gansu and Longshan culture in Shaanxi, played an intermediary role in this process.[citation needed]

Iron use in China dates as early as the Zhou dynasty (c. 1046 – 256 BC), but remained minimal. Chinese literature authored during the 6th century BC attests to knowledge of iron smelting, yet bronze continues to occupy the seat of significance in the archaeological and historical record for some time after this.[50] W. C. White argues that iron did not supplant bronze "at any period before the end of the Zhou dynasty (256 BC)" and that bronze vessels make up the majority of metal vessels through the Eastern Han period, or to 221 BC.[51]

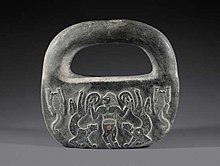

The Chinese bronze artefacts generally are either utilitarian, like spear points or adze heads, or "ritual bronzes", which are more elaborate versions in precious materials of everyday vessels, as well as tools and weapons. Examples are the numerous large sacrificial tripods known as dings; there are many other distinct shapes. Surviving identified Chinese ritual bronzes tend to be highly decorated, often with the taotie motif, which involves stylised animal faces. These appear in three main motif types: those of demons, symbolic animals, and abstract symbols.[52] Many large bronzes also bear cast inscriptions that are the bulk of the surviving body of early Chinese writing and have helped historians and archaeologists piece together the history of China, especially during the Zhou dynasty.

The bronzes of the Western Zhou document large portions of history not found in the extant texts that were often composed by persons of varying rank and possibly even social class. Further, the medium of cast bronze lends the record they preserve a permanence not enjoyed by manuscripts.[53] These inscriptions can commonly be subdivided into four parts: a reference to the date and place, the naming of the event commemorated, the list of gifts given to the artisan in exchange for the bronze, and a dedication.[54] The relative points of reference these vessels provide have enabled historians to place most of the vessels within a certain time frame of the Western Zhou period, allowing them to trace the evolution of the vessels and the events they record.[55]

Japan

[edit]

The Japanese archipelago saw the introduction of bronze during the early Yayoi period (c. 300 BC), which saw the introduction of metalworking and agricultural practices brought by settlers arriving from the continent. Bronze and iron smelting spread to the Japanese archipelago through contact with other ancient East Asian civilisations, particularly immigration and trade from the ancient Korean peninsula, and ancient mainland China. Iron was mainly used for agricultural and other tools, whereas ritual and ceremonial artefacts were mainly made of bronze.[clarification needed][56]

Korea

[edit]

On the Korean Peninsula, the Bronze Age began c. 1000–800 BC.[57][58] Initially centred around Liaoning and southern Manchuria, Korean Bronze Age culture exhibits unique typology and styles, especially in ritual objects.[citation needed]

The Mumun pottery period is named after the Korean name for undecorated or plain cooking and storage vessels that form a large part of the pottery assemblage over the entire length of the period, but especially between 850 and 550 BC. The Mumun period is known for the origins of intensive agriculture and complex societies in both the Korean Peninsula and the Japanese Archipelago.

The Middle Mumun pottery period culture of the southern Korean Peninsula gradually adopted bronze production (c. 700–600 BC) after a period when Liaoning-style bronze daggers and other bronze artefacts were exchanged as far as the interior part of the Southern Peninsula (c. 900–700 BC). The bronze daggers lent prestige and authority to the personages who wielded and were buried with them in high-status megalithic burials at south-coastal centres such as the Igeum-dong site. Bronze was an important element in ceremonies and for mortuary offerings until 100 BC.

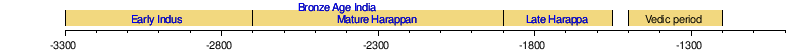

South Asia

[edit](Dates are approximate, consult linked articles for details)

Indus Valley

[edit]

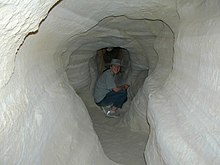

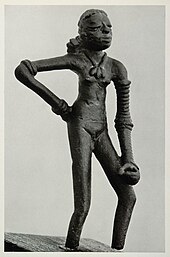

The Bronze Age on the Indian subcontinent began c. 3300 BC with the beginning of the Indus Valley Civilization. Inhabitants of the Indus Valley, the Harappans, developed new techniques in metallurgy and produced copper, bronze, lead, and tin. The Late Harappan culture (1900–1400 BC), overlapped the transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age; thus it is difficult to date this transition accurately. It has been claimed that a 6,000-year-old copper amulet manufactured in Mehrgarh in the shape of a wheel spoke is the earliest example of lost-wax casting in the world.[59][60]

The civilisation's cities were noted for their urban planning, baked brick houses, elaborate drainage systems, water supply systems, clusters of large non-residential buildings, and new techniques in handicraft (carnelian products, seal carving) and metallurgy (copper, bronze, lead, and tin).[61] The large cities of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa likely grew to contain between 30,000 and 60,000 people,[62] and the civilisation during its florescence may have contained between one and five million people.[63]

Southeast Asia

[edit]The Vilabouly Complex in Laos is a significant archaeological site for dating the origin of bronze metallurgy in Southeast Asia.

Thailand

[edit]In Ban Chiang, Thailand, bronze artefacts have been discovered that date to 2100 BC.[64] However, according to the radiocarbon dating on the human and pig bones in Ban Chiang, some scholars propose that the initial Bronze Age in Ban Chiang was in the late 2nd millennium.[65] In Nyaung-gan, Myanmar, bronze tools have been excavated along with ceramics and stone artefacts. Dating is still currently broad (3500–500 BC).[citation needed] Ban Non Wat, excavated by Charles Higham, was a rich site with over 640 graves excavated that gleaned many complex bronze items that may have had social value connected to them.[66]

Ban Chiang, however, is the most thoroughly documented site and has the clearest evidence of metallurgy when in Southeast Asia. With a rough date range from the late 3rd millennium BC to the 1st millennium AD, this site has artefacts such as burial pottery (dated 2100–1700 BC) and fragments of bronze and copper-base bangles. This technology suggested on-site casting from the beginning. The on-site casting supports the theory that bronze was first introduced in Southeast Asia from a different country.[67] Some scholars believe that copper-based metallurgy was disseminated from northwest and central China south and southwest via areas such as Guangdong and Yunnan and finally into southeast Asia c. 1000 BC.[65] Archaeology also suggests that Bronze Age metallurgy may not have been as significant a catalyst in social stratification and warfare in Southeast Asia as in other regions, and that social distribution shifted away from chiefdoms to a heterarchical network.[67] Data analyses of sites such as Ban Lum Khao, Ban Na Di, Non-Nok Tha, Khok Phanom Di, and Nong Nor have consistently led researchers to conclude that there was no entrenched hierarchy.[68]

Vietnam

[edit]Dating to the Neolithic, the first bronze drums, called the Dong Son drums, were uncovered in and around the Red River Delta regions of northern Vietnam and Southern China. These relate to the Dong Son culture of Vietnam.[69]

Archaeological research in Northern Vietnam indicates an increase in rates of infectious disease following the advent of metallurgy; skeletal fragments in sites dating to the early and mid-Bronze Age evidence a greater proportion of lesions than in sites of earlier periods.[70] There are a few possible implications of this. One is the increased contact with bacterial and/or fungal pathogens due to increased population density and land clearing/cultivation. Another implication is decreased levels of immunocompetence in the Metal Age due to changes in diet caused by agriculture. The last implication is that there may have been an emergence of infectious diseases that evolved into a more virulent form in the metal period.[70]

Europe

[edit]A few examples of named Bronze Age cultures in Europe roughly in relative order—dates are approximate.

The chosen cultures overlapped in time and the indicated periods do not fully correspond to their estimated extents.

Southeast Europe

[edit]

Radivojevic et al. (2013) reported the discovery of a tin bronze foil from the Pločnik archaeological site dated to c. 4650 BC as well as 14 other artefacts from Serbia and Bulgaria dated before 4000 BC, showing that early tin bronze was more common than previously thought and developed independently in Europe 1500 years before the first tin bronze alloys in the Near East. The production of complex tin bronzes lasted for about 500 years in the Balkans. The authors reported that evidence for the production of such complex bronzes disappears at the end of the 5th millennium BC, coinciding with the "collapse of large cultural complexes in north-eastern Bulgaria and Thrace". Tin bronzes using cassiterite tin were reintroduced to the area some 1500 years later.[3]

The oldest golden artefacts in the world are dated between 4600 and 4200 BC, and were found in the Necropolis of Varna. These artefacts are on display in the Varna Archaeological Museum.[72][73][74]

The Dabene Treasure was unearthed from 2004 to 2007 near Karlovo in central Bulgaria. The treasure consists of 20,000 gold jewellery items from 18 to 23 carats. The most important of them was a dagger made of gold and platinum with an unusual edge. The treasure was dated to the end of the 3rd millennium BC. Scientists suggest that the Karlovo valley used to be a major crafts centre that exported golden jewellery across Europe. It is considered one of the largest prehistoric golden treasures in the world.[citation needed]

Aegean

[edit]

The Aegean Bronze Age began c. 3200 BC, when civilisations first established a far-ranging trade network. This network imported tin and charcoal to Cyprus, where copper was mined and alloyed with tin to produce bronze. Bronze objects were then exported far and wide. Isotopic analysis of tin in some Mediterranean bronze artefacts suggests that they may have originated from Bronze Age Britain.[75]

Knowledge of navigation was well-developed by this time and reached a peak of skill not exceeded (except perhaps by Polynesian sailors) until 1730 when the invention of the chronometer enabled the precise determination of longitude.

The Minoan civilisation based in Knossos on the island of Crete appears to have coordinated and defended its Bronze Age trade. Ancient empires valued luxury goods in contrast to staple foods, leading to famine.[76]

Aegean collapse

[edit]

Bronze Age collapse theories have described aspects of the end of the Bronze Age in this region. At the end of the Bronze Age in the Aegean region, the Mycenaean administration of the regional trade empire followed the decline of Minoan primacy.[77] Several Minoan client states lost much of their population to famine and pestilence. This would indicate that the trade network may have failed, preventing the trade that would previously have relieved such famines and prevented illness caused by malnutrition. It is also known that in this era, the breadbasket of the Minoan empire—the area north of the Black Sea—also suddenly lost much of its population and thus probably some capacity to cultivate crops. Drought and famine in Anatolia may have also led to the Aegean collapse by disrupting trade networks, therefore preventing the Aegean from accessing bronze and luxury goods.[78]

The Aegean collapse has been attributed to the exhaustion of the Cypriot forests causing the end of the bronze trade.[79][80][81] These forests are known to have existed in later times, and experiments have shown that charcoal production on the scale necessary for the bronze production of the late Bronze Age would have exhausted them in less than 50 years.

The Aegean collapse has also been attributed to the fact that as iron tools became more common, the main justification for the tin trade ended, and that trade network ceased to function as it did formerly.[82] The colonies of the Minoan empire then suffered drought, famine, war, or some combination of the three, and had no access to the distant resources of an empire by which they could easily recover.

The Thera eruption occurred c. 1600 BC, 110 km (68 mi) north of Crete. Speculation includes that a tsunami from Thera (more commonly known today as Santorini) destroyed Cretan cities. A tsunami may have destroyed the Cretan navy in its home harbour, which then lost crucial naval battles; so that in the LMIB/LMII event (c. 1450 BC) the cities of Crete burned and the Mycenaean civilisation conquered Knossos. If the eruption occurred in the late 17th century BC as most chronologists believe, then its immediate effects belong to the Middle to Late Bronze Age transition, and not to the end of the Late Bronze Age, but it could have triggered the instability that led to the collapse first of Knossos and then of Bronze Age society overall.[citation needed] One such theory highlights the role of Cretan expertise in administering the empire, post-Thera. If this expertise was concentrated in Crete, then the Mycenaeans may have made political and commercial mistakes in administering the Cretan empire.[citation needed]

Archaeological findings, including some on the island of Thera, suggest that the centre of the Minoan civilisation at the time of the eruption was actually on Thera rather than on Crete.[83] According to this theory, the catastrophic loss of the political, administrative and economic centre due to the eruption, as well as the damage wrought by the tsunami to the coastal towns and villages of Crete, precipitated the decline of the Minoans. A weakened political entity with a reduced economic and military capability and fabled riches would have then been more vulnerable to conquest. Indeed, the Santorini eruption is usually dated to c. 1630 BC ,[84] while the Mycenaean Greeks first enter the historical record a few decades later, c. 1600 BC.[citation needed] The later Mycenaean assaults on Crete (c. 1450 BC) and Troy (c. 1250 BC) would have been a continuation of the steady encroachment of the Greeks upon the weakened Minoan world.[citation needed]

Central Europe

[edit]

In Central Europe, the Early Bronze Age Unetice culture (2300–1600 BC) includes numerous smaller groups like the Straubing, Adlerberg and Hatvan cultures. Some very rich burials, such as the one located at Leubingen with grave gifts crafted from gold, point to an increase of social stratification already present in the Unetice culture. Cemeteries of this period are small and rare. The Unetice culture was followed by the Middle Bronze Age (1600–1200 BC) tumulus culture, characterised by inhumation burials in tumuli barrows. In the eastern Hungarian Körös tributaries, the early Bronze Age first saw the introduction of the Mako culture, followed by the Otomani and Gyulavarsand cultures.

The late Bronze Age Urnfield culture (1300–700 BC) was characterised by cremation burials. It included the Lusatian culture in eastern Germany and Poland (1300–500 BC) that continues into the Iron Age. The Central European Bronze Age was followed by the Iron Age Hallstatt culture (700–450 BC). Important sites include Biskupin in Poland, Nebra in Germany, Vráble in Slovakia, and Zug-Sumpf in Switzerland.

German prehistorian Paul Reinecke described Bronze A1 (Bz A1) period (2300–2000 BC: triangular daggers, flat axes, stone wrist-guards, flint arrowheads) and Bronze A2 (Bz A2) period (1950–1700 BC: daggers with metal hilt, flanged axes, halberds, pins with perforated spherical heads, solid bracelets) and phases Hallstatt A and B (Ha A and B).

Southern Europe

[edit]

The Apennine culture was a technology complex in central and southern Italy spanning both the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age proper. The Camuni were an ancient people of uncertain origin who lived in Val Camonica, in present-day Lombardy, during the Iron Age, although groups of hunters, shepherds, and farmers are known to have lived in the area since the Neolithic.

Located in Sardinia and Corsica, the Nuragic civilisation lasted from the early Bronze Age (18th century BC) to the 2nd century AD, when the islands were already Romanised. They take their name from the characteristic Nuragic towers, which evolved from the pre-existing megalithic culture, which built dolmens and menhirs.

The towers are unanimously considered the best-preserved and largest megalithic remains in Europe. Their purpose is still debated: some scholars consider them monumental tombs, others as Houses of the Giants, other as fortresses, ovens for metal fusion, prisons, or finally temples for a solar cult. Near the end of the 3rd millennium BC, Sardinia exported to Sicily a culture that built small dolmens, trilithic or polygonal shaped, that served as tombs, as in the Sicilian dolmen of "Cava dei Servi". From this region, they reached Malta and other countries of Mediterranean basin.[85]

The Terramare was an early Indo-European civilisation in the area of what is now Pianura Padana in northern Italy, before the arrival of the Celts, and in other parts of Europe. They lived in square villages of wooden stilt houses. These villages were built on land, but generally near a stream, with roads forming a grid plan. The whole complex was of the nature of a fortified settlement. The Terramare culture was widespread in the Pianura Padana, especially along the Panaro river, between Modena and Bologna, and in the rest of Europe. The civilisation developed in the Middle and Late Bronze Age during the 17th–13th centuries BC.

The Castellieri culture developed in Istria during the Middle Bronze Age. It lasted for more than a millennium, from the 15th century BC until the Roman conquest in the 3rd century BC. It takes its name from the fortified boroughs (Castellieri, Friulian: cjastelir) that characterised the culture.

The Canegrate culture developed from the mid-Bronze Age (13th century BC) until the Iron Age in the Pianura Padana, in what are now western Lombardy, eastern Piedmont, and Ticino. It takes its name from the township of Canegrate, where, in the 20th century, some fifty tombs with ceramics and metal objects were found. The Canegrate culture migrated from the northwest part of the Alps and descended to Pianura Padana from the Swiss Alps passes and the Ticino.

The Golasecca culture developed starting from the late Bronze Age in the Po plain. It takes its name from Golasecca, a locality next to the Ticino, where in the early 19th century abbot Giovanni Battista Giani excavated its first findings comprising some 50 tombs with ceramics and metal objects. Remains of the Golasecca culture span an area of about 20,000 km2 (4,900,000 acres) south to the Alps, between the Po, Sesia, and Serio rivers, dating to the 9th–4th centuries BC.

Western Europe

[edit]Great Britain

[edit]

In Great Britain, the Bronze Age is considered to have been the period from c. 2100 to 750 BC. Migration brought new people to the islands from the continent.[86] Tooth enamel isotope research on bodies found in early Bronze Age graves around Stonehenge indicates that at least some of the migrants came from the area of present-day Switzerland. Another example site is Must Farm near Whittlesey, host to the most complete Bronze Age wheel ever to be found. The Beaker culture displayed different behaviours from earlier Neolithic people, and cultural change was significant. Integration is thought to have been peaceful, as many of the early henge sites were seemingly adopted by the newcomers. The rich Wessex culture developed in southern Britain at this time. Additionally, the climate was deteriorating; where once the weather was warm and dry it became much wetter as the Bronze Age continued, forcing the population away from easily defended sites in the hills and into the fertile valleys. Large livestock farms developed in the lowlands and appear to have contributed to economic growth and inspired increasing forest clearances. The Deverel-Rimbury culture began to emerge in the second half of the Middle Bronze Age (c. 1400–1100 BC) to exploit these conditions. Devon and Cornwall were major sources of tin for much of western Europe and copper was extracted from sites such as the Great Orme mine in northern Wales. Social groups appear to have been tribal but with growing complexity and hierarchies becoming apparent.

The burials, which until this period had usually been communal, became more individual. For example, whereas in the Neolithic a large chambered cairn or long barrow housed the dead, Early Bronze Age people buried their dead in individual barrows (commonly known and marked on modern British Ordnance Survey maps as tumuli), or sometimes in cists covered with cairns.

The greatest quantities of bronze objects in England were discovered in East Cambridgeshire, with the most important finds being the 6500-piece Isleham Hoard.[87] Alloying of copper with tin to make bronze was practiced soon after the discovery of copper. The techniques needed to deliberately alloy copper with zinc to form brass first arrived in Great Britain late in the first millennium BC.[88] One copper mine at Great Orme in North Wales, reached a depth of 70 metres.[89] At Alderley Edge in Cheshire, carbon dating has established mining at around 2280 to 1890 BC with a 95% probability.[90] The earliest identified metalworking site (Sigwells, Somerset) came much later, dated by globular urn-style pottery to c. the 12th century BC. The identifiable sherds from over 500 mould fragments included a perfect fit of the hilt of a sword in the Wilburton style held in Somerset County Museum.[91]

Atlantic Bronze Age

[edit]

The Atlantic Bronze Age as cultural geographic region is a cultural complex (c. 2100 – c. / 800 / 700 cal. BC) that includes different cultures in the context of the Atlantic Iberian Peninsula (Portugal, Andalucía, Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, País Vasco, Navarra and Castilla and León), the Atlantic France, Britain and Ireland, while the Atlantic Bronze Age as cultural complex of the final phase of the Bronze Age period is dated between c. 1350 and 700 BC. It is marked by economic and cultural exchange. Commercial contacts extend to Denmark and the Mediterranean. The Atlantic Bronze Age was defined by many distinct regional centres of metal production, unified by a regular maritime exchange of products.

Ireland

[edit]The Bronze Age in Ireland began c. 2000 BC when copper was alloyed with tin and used to manufacture Ballybeg type flat axes and associated metalwork. The preceding period is known as the Copper Age and is characterised by the production of flat axes, daggers, halberds and awls in copper. The period is divided into three phases: Early Bronze Age (2000–1500 BC), Middle Bronze Age (1500–1200 BC), and Late Bronze Age (1200 – c. 500 BC). Ireland is known for a relatively large number of Early Bronze Age burials. The country's stone circles and stone rows were built during this period.[92]

One of the characteristic types of artefacts of the Early Bronze Age in Ireland is the flat axe. There are five main types of flat axes: Lough Ravel crannog (c. 2200 BC), Ballybeg (c. 2000 BC), Killaha (c. 2000 BC), Ballyvalley (c. 2000–1600 BC), Derryniggin (c. 1600 BC), and a number of metal ingots in the shape of axes.[93]

Northern Europe

[edit]

The Bronze Age in Northern Europe spans the 2nd millennium BC, (Unetice culture, Urnfield culture, Tumulus culture, Terramare culture and Lusatian culture) lasting until c. 600 BC. The Northern Bronze Age was both a period and a Bronze Age culture in Scandinavian pre-history, c. 1700–500 BC, with sites as far east as Estonia. Succeeding the Late Neolithic culture, its ethnic and linguistic affinities are unknown in the absence of written sources. It was followed by the Pre-Roman Iron Age.

Even though Northern European Bronze Age cultures came relatively late, and came into existence via trade, sites present rich and well-preserved objects made of wool, wood and imported Central European bronze and gold. Many rock carvings depict ships, and the large stone burial monuments known as stone ships suggest that shipping played an important role. Thousands of rock carvings depict ships, most probably representing sewn plank-built canoes for warfare, fishing, and trade. These may have a history as far back as the neolithic period and continue into the Pre-Roman Iron Age, as shown by the Hjortspring boat. There are many mounds and rock carving sites from the period. Numerous artefacts of bronze and gold are found. No written language existed in the Nordic countries during the Bronze Age. The rock carvings have been dated through comparison with depicted artefacts.

Eastern Europe

[edit]

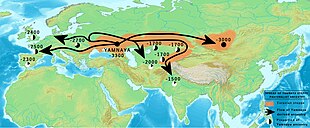

The Yamnaya culture (c. 3300–2600 BC) was a Late Copper Age/Early Bronze Age culture of the Pontic-Caspian steppe[94][95] associated with early Indo-Europeans. It was followed on the steppe by the Catacomb culture (c. 2800–2200 BC) and the Poltavka culture (c. 2800–2200 BC). The closely-related Corded Ware culture in the forest-steppe region to the north (c. 3000–2350 BC) spread eastwards with the Fatyanovo culture (c. 2900–2050 BC), which subsequently developed into the Abashevo culture (c. 2200–1850 BC) and the Sintashta culture (c. 2200–1750 BC). The earliest known chariots have been found in Sintashta burials and there is earlier evidence for chariot use in the Abashevo culture. The Sintashta culture expanded further eastwards into central Asia becoming the Andronovo culture, while the Srubnaya culture (c. 1900–1200 BC) continued the use of chariots in eastern Europe.

Caucasus

[edit]Arsenical bronze artefacts of the Maykop culture in the North Caucasus have been dated to around the 4th millennium BC.[96] This innovation resulted in the circulation of arsenical bronze technology through southern and eastern Europe.[97]

| Part of a series on |

| Human history and prehistory |

|---|

| ↑ before Homo (Pliocene epoch) |

| ↓ Future (Holocene epoch) |

Africa

[edit]Sub-Saharan Africa

[edit]Iron and copper smelting appeared around the same time in most parts of Africa.[16][98] As such, most Classical African civilisations outside Egypt did not experience a distinct Bronze Age. Evidence for iron smelting appears earlier or at the same time as copper smelting in Nigeria c. 900–800 BC, Rwanda and Burundi c. 700–500 BC and Tanzania c. 300 BC.[98][99][100]

There is a longstanding debate about whether copper and iron metallurgy were independently developed in sub-Saharan Africa or introduced from the outside across the Sahara from North Africa or the Indian Ocean.[98] Evidence for theories of independent development and outside introduction are scarce and the subject of active scholarly debate.[98] Scholars have suggested that both the relative dearth of archaeological research in sub-Saharan Africa as well as long-standing prejudices have limited or biased our understanding of pre-historic metallurgy on the continent.[99][101][102] One scholar characterised the state of historical knowledge: "To say that the history of metallurgy in sub-Saharan Africa is complicated is perhaps an understatement."[102]

West Africa

[edit]Copper smelting took place in West Africa prior to the appearance of iron smelting in the region. Evidence for copper smelting furnaces was found near Agadez, Niger that has been dated as early as 2200 BC.[99] However, evidence for copper production in this region before 1000 BC is debated.[103][16][99] Evidence of copper mining and smelting has been found at Akjoujt, Mauretania that suggests small scale production c. 800—400 BC.[99]

Americas

[edit]The Moche culture of South America independently discovered and developed bronze smelting.[104] Bronze technology was developed further by the Inca and widely used for utilitarian objects and for sculpture.[105][unreliable source?] A later appearance of limited bronze smelting in western Mexico suggests either contact of that region with Andean civilisations or separate discovery of the technology. The Calchaquí people of northwestern Argentina had bronze technology.[106]

Trade

[edit]Trade and industry played a major role in the development of Bronze Age civilisations. With artefacts of the Indus Valley Civilisation found in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, it is clear that these civilisations were not only in touch with one another, but also trading. Early long-distance trade was limited almost exclusively to luxury goods like spices, textiles, and precious metals. Not only did this make cities with ample amounts of these products rich, but it also led to an intermingling of cultures for the first time in history.[107]

Trade routes were not just on land. The first and most extensive trade routes were along rivers such as the Nile, the Tigris, and the Euphrates, which led to the growth of cities on the banks of these rivers. The later domestication of camels also helped encourage trade routes overland, linking the Indus Valley with the Mediterranean. This further led to towns appearing where there was a pit-stop or caravan-to-ship port.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "The Metal Ages". Encyclopædia Britannica. 16 September 2024.

- ^ McClellan III, James E.; Dorn, Harold (14 April 2006). Science and Technology in World History (2nd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8018-8360-6.

- ^ a b Radivojevic, M.; Rehren, T.; Kuzmanovic-Cvetkovic, J.; Jovanovic, M.; Northover, J. P. (2013). "Tainted ores and the rise of tin bronzes in Eurasia, c. 6500 years ago". Antiquity. 87 (338): 1030–1045. doi:10.1017/S0003598X0004984X.

- ^ Sljivar, D.; Boric, D.; et al. (2014). "Context is everything: comments on Radivojevic et al. (2013)". Antiquity. 88 (342): 1310–1315. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00115480. S2CID 163137272.

- ^ Radivojevic, M.; Rehren, Th.; Kuzmanovic-Cvetkovic, J.; Jovanovic, M. (2014). "Context is everything indeed: a response to Sljivar and Boric". Antiquity. 88 (342): 1315–1319. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00115492. S2CID 163091248.

- ^ The Near East period dates and phases are unrelated to the bronze chronology of other world regions.

- ^ Piotr Bienkowski, Alan Ralph Millard, eds. Dictionary of the ancient Near East. p. 60.

- ^ Amélie Kuhr. The Ancient Near East, c. 3000–330 BC. p. 9.

- ^ Lev, Ron; Bechar, Shlomit; Boaretto, Elisabetta (2021). "Hazor Eb III City Abandonment and Iba People Return: Radiocarbon Chronology and ITS Implications". Radiocarbon. 63 (5): 1453. Bibcode:2021Radcb..63.1453L. doi:10.1017/RDC.2021.76.

- ^ Killebrew, Ann E. (2013). The Philistines and Other 'Sea Peoples' in Text and Archaeology. Society of Biblical Literature Archaeology and biblical studies. Vol. 15. Society of Biblical Literature. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-58983-721-8.

First coined in 1881 by the French Egyptologist G. Maspero (1896), the somewhat misleading term 'Sea Peoples' encompasses the ethnonyms Lukka, Sherden, Shekelesh, Teresh, Eqwesh, Denyen, Sikil / Tjekker, Weshesh, and Peleset (Philistines). [Footnote: The modern term 'Sea Peoples' refers to peoples that appear in several New Kingdom Egyptian texts as originating from 'islands' (tables 1–2; Adams and Cohen, this volume; see, e.g., Drews 1993, 57 for a summary). The use of quotation marks in association with the term 'Sea Peoples' in our title is intended to draw attention to the problematic nature of this commonly used term. It is noteworthy that the designation 'of the sea' appears only concerning the Sherden, Shekelesh, and Eqwesh. Subsequently, this term was applied somewhat indiscriminately to several additional ethnonyms, including the Philistines, who are portrayed in their earliest appearance as invaders from the north during the reigns of Merenptah and Ramesses Ill (see, e.g., Sandars 1978; Redford 1992, 243, n. 14; for a recent review of the primary and secondary literature, see Woudhuizen 2006). Henceforth the term Sea Peoples will appear without quotation marks.

- ^ Drews, Robert (1993). The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe ca. 1200 B.C. Princeton University Press. pp. 48–61. ISBN 0691025916.

The thesis that a great 'migration of the Sea Peoples' occurred ca. 1200 B.C. is supposedly based on Egyptian inscriptions, one from the reign of Merneptah and another from the reign of Ramesses III. Yet in the inscriptions themselves, such a migration nowhere appears. After reviewing what the Egyptian texts have to say about 'the sea peoples', one Egyptologist (Wolfgang Helck) recently remarked that although some things are unclear, 'eins ist aber sicher: Nach den ägyptischen Texten haben wir es nicht mit einer "Völkerwanderung" zu tun.' Thus, the migration hypothesis is based not on the inscriptions themselves but on their interpretation.

- ^ a b Karin Sowada and Peter Grave. Egypt in the Eastern Mediterranean during the Old Kingdom.

- ^ Lukas de Blois and R. J. van der Spek. An Introduction to the Ancient World. p. 14.

- ^ Hansen, M. (2000). A comparative study of thirty city-state cultures: An investigation conducted by the Copenhagen Polis Centre. Copenhagen, Denmark: Det Kongelike Danske Videnskabernes Selskab. p. 68.

- ^ a b Childs, S. Terry; Killick, David (1993). "Indigenous African Metallurgy: Nature and Culture". Annual Review of Anthropology. 22: 317–337. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.22.1.317. JSTOR 2155851.

- ^ a b c Miller, Duncan E.; van der Merwe, Nikolaas J. (1994). "Early Metal Working in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review of Recent Research". The Journal of African History. 35 (1): 1–36. doi:10.1017/s0021853700025949. JSTOR 182719. S2CID 162330270.

- ^ Othmar Keel and Christoph Uehlinger. Gods, goddesses, and images of God in ancient Israel, 1998. p. 17. "The first phase (Middle Bronze Age IIA) runs roughly parallel to the Egyptian Twelfth Dynasty".

- ^ Bruce G. Trigger. Ancient Egypt: A Social History. 1983. p. 137. "... for the Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period it is the Middle Bronze Age".

- ^ Dalton, Ormonde Maddock; Franks, Augustus Wollaston; Read, C. H. (1905). The treasure of the Oxus. London: British Museum.

- ^ Masson, V. M. "Bronze Age in Khorasan and Transoxiana". In Dani, A. H.; Masson, Vadim Mikhaĭlovich (eds.). History of civilizations of Central Asia. Vol. The dawn of civilization: earliest times to 700 BC.

- ^ Possehl, G. L. (1986)., Kulli: An exploration of ancient civilization in Asia. Durham, North Carolina: Carolina Academic Press.

- ^ Piggott, S. (1961). Prehistoric India to 1000 B.C. Baltimore: Penguin.

- ^ Hansen, Mogens Herman (2000). A Comparative Study of Thirty City-state Cultures: An Investigation. Vol. 21. Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab. p. 57. ISBN 978-8778761774. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ under Shamshi-Adad I.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel (1996). "Ethnicity and origin of the Iron I settlers in the Highlands of Canaan: Can the real Israel stand up?". The Biblical Archaeologist. 59 (4): 198–212. doi:10.2307/3210562. JSTOR 3210562. S2CID 164201705.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel (1988). The archaeology of the Israelite settlement. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. ISBN 965-221-007-2.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel; Naʼaman, Nadav, eds. (1994). From nomadism to monarchy: archaeological and historical aspects of early Israel. Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi. ISBN 965-217-117-4.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel (1996). "The archaeology of the United Monarchy: an alternative view". Levant. 28 (1): 177–187. doi:10.1179/lev.1996.28.1.177.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2002). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Sacred Texts. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-86913-6.

- ^ Spengler, Robert N. (1 September 2015). "Agriculture in the Central Asian Bronze Age". Journal of World Prehistory. 28 (3): 215–253. doi:10.1007/s10963-015-9087-3. ISSN 1573-7802. S2CID 161968192.

- ^ Vidale, Massimo, 2017. Treasures from the Oxus, I. B. Tauris, pp. 8–10 & Table 1.

- ^ Possehl, Gregory L. (2002). The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Rowman Altamira. pp. 215–232. ISBN 978-0-7591-0172-2.

- ^ Narasimhan, Vagheesh M.; et al. (2019). "The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia". Science. 365 (6457). bioRxiv 10.1101/292581. doi:10.1126/science.aat7487. PMC 6822619. PMID 31488661.

- ^ a b c d Keys, David (January 2009). "Scholars crack the code of an ancient enigma". BBC History Magazine. 10 (1): 9.

- ^ White, Joyce; Hamilton, Elizabeth (2009). "The Transmission of Early Bronze Technology to Thailand: New Perspectives". Journal of World Prehistory. 22 (4): 357–397. doi:10.1007/s10963-009-9029-z. S2CID 9400588.

- ^ Lalueza-Fox, C.; Sampietro, M. L.; Gilbert, M. T.; Castri, L.; Facchini, F.; Pettener, D.; Bertranpetit, J. (2004). "Unravelling migrations in the steppe: Mitochondrial DNA sequences from ancient central Asians". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 271 (1542): 941–947. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2698. PMC 1691686. PMID 15255049.

- ^ Keyser, Christine; Bouakaze, Caroline; Crubézy, Eric; Nikolaev, Valery G.; Montagnon, Daniel; Reis, Tatiana; Ludes, Bertrand (2009). "Ancient DNA provides new insights into the history of south Siberian Kurgan people". Human Genetics. 126 (3): 395–410. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0683-0. PMID 19449030. S2CID 21347353.

- ^ Martini, I. Peter (2010). Landscapes and Societies: Selected Cases. Springer. p. 310. ISBN 978-90-481-9412-4.

- ^ Higham, Charles (2004). Encyclopedia of ancient Asian civilizations. Infobase. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-8160-4640-9.

- ^ The archaeological term "Bronze Age" was first introduced for Europe in the 1830s and soon extended to the Near East. By the 1860s, there was some debate as to whether the term should be extended to China (John Lubbock, Prehistoric Times (1868), cited after The Athenaeum No. 2121, 20 June 1868, p. 870).

- ^ Robert L. Thorp, China in the Early Bronze Age: Shang Civilization, University of Pennsylvania Press (2013).

- ^ " Without entering on the vexed question whether or not there ever was a bronze age in any part of the world distinguished by the sole use of that metal, in China and Japan to the present day, amid an iron age, bronze is in constant use for cutting instruments, either alone or in combination with steel." The Rectangular Review, Volume 1 (1871), p. 408

- ^ Wu Hung (1995). Monumentality in Early Chinese Art and Architecture. pp. 11, 13 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Chang, K. C.: "Studies of Shang Archaeology", pp. 6–7, 1. Yale University Press, 1982.

- ^ Chang, K. C.: "Studies of Shang Archaeology", p. 1. Yale University Press, 1982.

- ^ "Teaching Chinese Archaeology, Part Two". Nga.gov. Archived from the original on 13 February 2008. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ Li-Liu; The Chinese Neolithic, Cambridge University Press, 2005. Shang and Zhou Dynasties: The Bronze Age of China Heilbrunn Timeline Archived 10 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 13 May 2010

- ^ Romgard, Jan (2008). "Questions of Ancient Human Settlements in Xinjiang and the Early Silk Road Trade, with an Overview of the Silk Road Research Institutions and Scholars in Beijing, Gansu, and Xinjiang" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers (185): 30–32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ Bai, Yunxiang (2003). "A Discussion on Early Metals and the Origins of Bronze Casting in China" (PDF). Chinese Archaeology. 3 (1): 157–165. doi:10.1515/char.2003.3.1.157. S2CID 164920328.

- ^ Barnard, N. "Bronze Casting and Bronze Alloys in Ancient China", p. 14. The Australian National University and Monumenta Serica, 1961.

- ^ White, W. C. "Bronze Culture of Ancient China", p. 208. University of Toronto Press, 1956.

- ^ von Erdberg, Elizabeth (1993). Ancient Chinese Bronzes: Terminology and Iconology. Siebenbad-Verlag. p. 20. ISBN 978-3877470633.

- ^ Shaughnessy, E. L. "Sources of Western Zhou History", pp. xv–xvi. University of California Press, 1982.

- ^ Shaughnessy, E. L. "Sources of Western Zhou History", pp. 76–83. University of California Press, 1982.

- ^ Shaughnessy, E. L. "Sources of Western Zhou History", p. 107.

- ^ "Kyoto National Museum". Kyoto National Museum. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ^ Eckert, Carter J.; Lee, Ki-Baik; Lew, Young Ick; Robinson, Michael; Wagner, Edward W. (1990). Korea, Old and New: A History. Korea Institute, Harvard University. p. 9. ISBN 978-0962771309.

- ^ "1000 BC to 300 AD: Korea". Asia for Educators. Columbia University. Archived from the original on 12 October 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ Bertrand, L.; Jarrige, J.-F.; Réfrégiers, M.; Robbiola, L.; Séverin-Fabiani, T.; Mille, B.; Thoury, M. (15 November 2016). "High spatial dynamics-photoluminescence imaging reveals the metallurgy of the earliest lost-wax cast object". Nature Communications. 7: 13356. Bibcode:2016NatCo...713356T. doi:10.1038/ncomms13356. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5116070. PMID 27843139.

- ^ "Centre for Cultural Resources and Training (CCRT)". ccrtindia.gov.in. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Wright, Rita P. (2010). The Ancient Indus: Urbanism, Economy, and Society. Cambridge University Press. pp. 115–125. ISBN 978-0-521-57219-4.

- ^ Dyson, Tim (2018). A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day. Oxford University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-19-882905-8.

Mohenjo-daro and Harappa may each have contained between 30,000 and 60,000 people (perhaps more in the former case). Water transport was crucial for the provisioning of these and other cities. That said, the vast majority of people lived in rural areas. At the height of the Indus valley civilization the subcontinent may have contained 4–6 million people.

- ^ McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-ClIO. p. 387. ISBN 978-1-57607-907-2.

The enormous potential of the greater Indus region offered scope for huge population increase; by the end of the Mature Harappan period, the Harappans are estimated to have numbered somewhere between 1 and 5 million, probably well below the region's carrying capacity.

- ^ "Bronze from Ban Chiang, Thailand: A view from the Laboratory" (PDF). Penn Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ a b Higham, C.; Higham, T.; Ciarla, R.; Douka, K.; Kijngam, A.; Rispoli, F. (2011). "The Origins of the Bronze Age of Southeast Asia". Journal of World Prehistory. 24 (4): 227–274. doi:10.1007/s10963-011-9054-6. S2CID 162300712.

- ^ Higham, C. F. W. (2011). "The Bronze Age of Southeast Asia: New insight on social change from Ban Non Wat". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 21 (3): 365–389. doi:10.1017/s0959774311000424. S2CID 162729367.

- ^ a b White, J. C. (1995). "Incorporating Heterarchy into Theory on Socio-political Development: The Case from Southeast Asia". Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association. 6 (1): 101–123. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.522.1061. doi:10.1525/ap3a.1995.6.1.101. S2CID 129026022.

- ^ O'Reilly, D. J. W. (2003). "Further evidence of heterarchy in Bronze Age Thailand". Current Anthropology. 44 (2): 300–306. doi:10.1086/367973. S2CID 145310194.

- ^ Taylor, Keith Weller (1991). The Birth of Vietnam. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520074170.

- ^ a b Oxenham, M. F.; Thuy, N. K.; Cuong, N. L. (2005). "Skeletal evidence for the emergence of infectious disease in bronze and iron age northern Vietnam". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 126 (4): 359–376. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20048. PMID 15386222.

- ^ Molloy, Barry; et al. (2023). "Early Chariots and Religion in South-East Europe and the Aegean During the Bronze Age: A Reappraisal of the Dupljaja Chariot in Context". European Journal of Archaeology. 27 (2): 149–169. doi:10.1017/eaa.2023.39.

- ^ Grande, Lance (15 November 2009). Gems and Gemstones: Timeless Natural Beauty of the Mineral World. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-30511-0. Archived from the original on 1 November 2022.

- ^ Curry, Andrew. "Mystery of the Varna Gold: What Caused These Ancient Societies to Disappear?". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ Daley, Jason. "World's Oldest Gold Object May Have Just Been Unearthed in Bulgaria". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ Carl Waldman, Catherine Mason. Encyclopedia of European peoples: Volume 1. 2006. p. 524.

- ^ Lancaster, H. O. (1990). Expectations of life: A study in the demography, statistics, and history of world mortality. New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 228.

- ^ Drews, R. (1993). The end of the Bronze Age: Changes in warfare and the catastrophe ca. 1200 B.C. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

- ^ Neer, Richard T. (2012). Greek Art and Archaeology. New York: Thames & Hudson. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-500-28877-1.

- ^ Swiny, S., Hohlfelder, R. L., & Swiny, H. W. (1998). Cities on the Sea. Res maritime: Cyprus and the eastern Mediterranean from prehistory to late antiquity: proceedings of the Second International Symposium "Cities on the Sea", Nicosia, Cyprus, 18–22 October 1994. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press.

- ^ Creevey, B. (1994). The forest resources of Bronze Age Cyprus.

- ^ A. Bernard Knapp, Steve O. Held, and Sturt W. Manning. The prehistory of Cyprus: Problems and prospects.

- ^ Lockard, Craig A. (2009). Societies, Networks, and Transitions: To 600. Wadsworth Publishing Company. p. 96.

- ^ Antonopoulos, John (1 March 1992). "The great Minoan eruption of Thera volcano and the ensuing tsunami in the Greek Archipelago". Natural Hazards. 5 (2): 153–168. Bibcode:1992NatHa...5..153A. doi:10.1007/BF00127003. ISSN 1573-0840. S2CID 129836887.

- ^ Rackham, Oliver; Moody, Jennifer (1996). The Making of the Cretan Landscape. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-3647-7.

- ^ Piccolo, Salvatore, op. cit., pp. 1 onwards.

- ^ a b Barras, Colin (27 March 2019). "Story of most murderous people of all time revealed in ancient DNA". New Scientist.

- ^ Hall & Coles, pp. 81–88.

- ^ Craddock, Paul; Cowell, Michael; Stead, Ian (September 2004). "Britain's First Brass". The Antiquaries Journal. 84: 339–346. doi:10.1017/S000358150004587X. ISSN 1758-5309.

- ^ O'Brien, W. (1997). Bronze Age Copper Mining in Britain and Ireland. Shir. ISBN 978-0-7478-0321-8.

- ^ Timberlake, S.; Prag, A. J. N. W. (2005). The Archaeology of Alderley Edge: Survey, excavation and experiment in an ancient mining landscape. Oxford: John and Erica Hedges. p. 396. doi:10.30861/9781841717159. ISBN 978-1841717159.

- ^ Tabor, Richard (2008). Cadbury Castle: A hillfort and landscapes. Stroud: The History Press. pp. 61–69. ISBN 978-0-7524-4715-5.

- ^ Power (1992), p. 23.

- ^ Waddell; Eogan.

- ^ Kristiansen, Kristian; Allentoft, Morten E.; Willerslev, Eske (2017). "Re-theorising mobility and the formation of culture and language among the Corded Ware Culture in Europe". Antiquity. 91 (356): 334–347. doi:10.15184/aqy.2017.17. hdl:1887/70150. ISSN 0003-598X.

- ^ Villalba-Mouco, Vanessa; Oliart, Camila; Haak, Wolfgang (19 November 2021). "Genomic transformation and social organization during the Copper Age–Bronze Age transition in southern Iberia". Science Advances. 7 (47): eabi7038. Bibcode:2021SciA....7.7038V. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abi7038. hdl:10810/54399. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 8597998. PMID 34788096.

- ^ Philip L. Kohl. The making of Bronze Age Eurasia. p. 58.

- ^ Gimbutas (1973). "The Beginning of the Bronze Age in Europe and the Indo-Europeans 3500–2500 BC". Journal of Indo-European Studies. 1: 177.

- ^ a b c d Childs, S. Terry (2008). "Metallurgy in Africa". In Selin, Helaine (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer. pp. 1596–1601. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4425-0_8776. ISBN 978-1-4020-4425-0.

- ^ a b c d e Holl, Augustin F. C. (2009). "Early West African Metallurgies: New Data and Old Orthodoxy". Journal of World Prehistory. 22 (4): 415–438. doi:10.1007/s10963-009-9030-6. S2CID 161611760.

- ^ Alpern, Stanley B. (2005). "Did They or Didn't They Invent It? Iron in Sub-Saharan Africa". History in Africa. 32: 41–94. doi:10.1353/hia.2005.0003. JSTOR 20065735. S2CID 162880295.

- ^ Killick, David (2009). "Cairo to Cape: The Spread of Metallurgy Through Eastern and Southern Africa". Journal of World Prehistory. 22 (4): 399–414. doi:10.1007/s10963-009-9025-3. S2CID 162458882.

- ^ a b Chirikure, Shadreck (2010). "On Evidence, Ideas and Fantasy: The Origins of Iron in Sub-Saharan Africa: Thoughts on É. Zagato & A. F. C. Holl's 'On the Iron Front'". Journal of African Archaeology. 8 (1): 25–28. doi:10.3213/1612-1651-10156. JSTOR 43135498.

- ^ Killick, David; van der Merwe, Nikolaas J.; Gordon, Robert B.; Grebenart, Danilo (1988). "Reassessment of the Evidence for Early Metallurgy in Niger, West Africa". Journal of Archaeological Science. 15 (4): 367–3944. Bibcode:1988JArSc..15..367K. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(88)90036-2.

- ^ "El bronce y el horizonte medio". lablaa.org. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 22 March 2010.

- ^ Gutierrez, Antonio. "Inca Metallurgy". Incas.homestead.com. Archived from the original on 31 January 2009. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ Ambrosetti, El bronze de la región calchaquí, Buenos Aires, 1904.[1]. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ^ Kristiansen, Kristian (26 November 2015). "Connected Histories: the Dynamics of Bronze Age Interaction and Trade 1500–1100 BC". Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. 81: 361–392. doi:10.1017/ppr.2015.17.

References

[edit]- Eogan, George (1983). The Hoards of the Irish Later Bronze Age. Dublin University College. ISBN 0-901120-77-4.

- Bradley, Richard; Hall, David; Coles, John; Entwistle, Roy; Raymond, Frances (1994). Fenland Survey. London: English Heritage. ISBN 1-85074-477-7.

- Pernicka, E., Eibner, C., Öztunah, Ö., Wagener, G. A. (2003). "", In: Wagner, G. A., Pernicka, E. and Uerpmann, H-P. (eds), Troia and the Troad: scientific approaches, Natural science in archaeology, Berlin, Germany; London, England: Springer, ISBN 3-540-43711-8, pp.

- Piccolo, Salvatore (2013). Ancient Stones: The Prehistoric Dolmens of Sicily. Abingdon (Great Britain): Brazen Head Publishing, ISBN 978-09565106-2-4

- Power, Denis. Archaeological inventory of County Cork, Volume 3: Mid Cork. Stationery Office, 1992. ISBN 978-0-7076-4933-7

- Waddell, John (1998). The prehistoric archaeology of Ireland, Galway University Press, 433 p., ISBN 1-901421-10-4

Further reading

[edit]- Childe, V. G. (1930). The bronze age. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- Figueiredo, Elin (2010). "Smelting and Recycling Evidences from the Late Bronze Age habitat site of Baioes" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. 37 (7): 1623–1634. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2010.01.023. hdl:10451/9795. S2CID 53316689.

- Fong, Wen, ed. (1980). The great bronze age of China: an exhibition from the People's Republic of China. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-226-1. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- Kelleher, Bradford (1980). Treasures from the Bronze Age of China: An exhibition from the People's Republic of China, the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Ballantine. ISBN 978-0-87099-230-8.

- Wagner, Donald B. (1993). Iron and Steel143–172 in Ancient China. Brill.

- Kuijpers, M. H. G. (2008). Bronze Age metalworking in the Netherlands (c. 2000–800 BC): A research into the preservation of metallurgy related artefacts and the social position of the smith. Leiden, Netherlands: Sidestone. ISBN 978-9088900150. Archived from the original on 5 February 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- Li; et al. (2010). "Evidence that a West-East admixed population lived in the Tarim Basin as early as the early Bronze Age". BMC Biology. 8: 15. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-15. PMC 2838831. PMID 20163704.

- Müller-Lyer, Franz Carl; Lake, E. C.; Lake, H. A. (1921). The history of social development. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Pittman, Holly (1984). Art of the Bronze Age: southeastern Iran, western Central Asia, and the Indus Valley. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-365-7. Archived from the original on 26 December 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- Roberts, B. W.; Thornton, C. P.; Pigott, V. C. (2009). "Development of Metallurgy in Eurasia". Antiquity. 83 (322): 112–122. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00099312. S2CID 163062746.

- Siklosy; et al. (2009). "Bronze Age volcanic event recorded in stalagmites by combined isotope and trace element studies". Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 23 (6): 801–808. Bibcode:2009RCMS...23..801S. doi:10.1002/rcm.3943. PMID 19219896.

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Bronze Age Experimental Archeology and Museum Reproductions

- Umha Aois – Reconstructed Bronze Age metal casting

- Umha Aois – ancient bronze casting videoclip

- Aegean and Balkan Prehistory articles, site-reports and bibliography database concerning the Aegean, Balkans and Western Anatolia

- "The Transmission of Early Bronze Technology to Thailand: New Perspectives"

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016)

- Seafaring