Quranic studies

Quranic studies is the academic study of the Quran, the central religious text of Islam. Like in biblical studies, the field uses and applies a diverse set of disciplines and methods, such as philology, textual criticism, lexicography, codicology, literary criticism, comparative religion, and historical criticism.[1][2][3][4] The beginning of modern Quranic studies began among German scholars from the 19th century.[5]

Quranic studies has three primary goals. The first goal is to understand the original meaning, sources, history of revelation, and the history of the recording and transmission, of the Quran. The second is to trace how the Quran was received by people, including how it was understood and interpreted (exegesis), throughout the centuries. The third is a study and appreciation and of the Quran as literature independently of the other two goals.[6]

Historical criticism

[edit]Quranic studies employs the historical-critical method (HCM) as its primary methodological apparatus, which is the approach that emphasizes a process that "delays any assessment of scripture’s truth and relevance until after the act of interpretation has been carried out".[1] To read a text critically

means to suspend inherited presuppositions about its origin, transmission, and meaning, and to assess their adequacy in the light of a close reading of that text itself as well as other relevant sources ... This is not to say that scripture should conversely be assumed to be false and mortal, but it does open up the very real possibility that an interpreter may find scripture to contain statements that are, by his own standards, false, inconsistent, or trivial. Hence, a fully critical approach to the Bible, or to the Qur’an for that matter, is equivalent to the demand, frequently reiterated by Biblical scholars from the eighteenth century onwards, that the Bible is to be interpreted in the same manner as any other text.[1]

By contrast, to read a text historically would mean to

require the meanings ascribed to it to have been humanly ‘thinkable’ or ‘sayable’ within the text’s original historical environment, as far as the latter can be retrospectively reconstructed. At least for the mainstream of historical-critical scholarship, the notion of possibility underlying the words ‘thinkable’ and ‘sayable’ is informed by the principle of historical analogy – the assumption that past periods of history were constrained by the same natural laws as the present age, that the moral and intellectual abilities of human agents in the past were not radically different from ours, and that the behaviour of past agents, like that of contemporary ones, is at least partly explicable by recourse to certain social and economic factors.[1]

Textual criticism

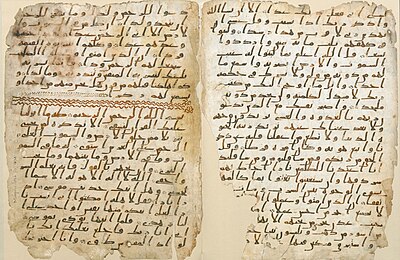

[edit]Today, the field of applying the methods of textual criticism to the Quran is still in its infancy. The most significant development in recent years has been the digitization of early Quran manuscripts. In the same timeframe, the study of Quran manuscripts has also picked up.[7]

Companion codices

[edit]When Muhammad, the authoritative source of divine revelation among his followers (known as his Companions) died, it became necessary for the Companions to collect his teachings into a single authoritative document so that they would not be lost. Collections of his teachings were written down into codices, a type of document that is the ancestor of the modern book. The unit of division of these Quran codices was the surah, which is roughly equivalent to a chapter in a book today. The most important collection was the Uthmanic codex, which received its name due to it being canonized during the reign of the caliph Uthman around 650 AD, at which point it became the authoritative written codification of the Quran in Islam. Before this event, other Companions of Muhammad had also created their own, slightly different codices of the Quran. In Islamic history, codices have been attributed to Abdullah ibn Masud, Ubayy ibn Ka'b, and Abu Musa al-Ash'ari.[8]

The codex of Ibn Mas'ud and the codex of Ubayy ibn Ka'b are well understood, because they survived up until the eleventh century, and many Islamic authorities described their variants in detail. By contrast, very little is known about the codex of Al-Ash'ari. No manuscript of any of these texts has survived up until the present day, although the evidence that they once existed is strong enough that is has widely convinced historians. In addition to the description of these codices by several authorities in different times and regions, the discovery of the Sanaa manuscript, which is independent of the Uthmanic codex, has provided concrete manuscript evidence for a Quran that contains variants attributed to the codices of the Companions.[9][10]

The main difference between the codices of Uthman and Ibn Mas'ud is that the codex of Ibn Mas'ud did not include Surah al-Fatihah, or the final two surahs of the Uthmanic codex (Al-Falaq and Al-Nas), known as the Al-Mu'awwidhatayn ("The Two Protectors"). The codex of Ubayy includes all the surahs of the Uthmanic codex, but it also possesses another two beyond them.[11]

Canonization

[edit]Tradition holds that the Quran was canonized by the caliph Uthman around 650 AD, which immediately became the standard Quran. In recent decades, a new controversy has emerged over the timing of this canonization event, and whether it took placed during the time of Uthman or under a later caliph. Behnam Sadeghi and Mohsen Goudarzi classify members of the field into four camps on this issue: traditionalists, revisionists, skeptics, and neo-traditionalists.[12] Traditionalists accept the traditional account of the formation of the Quran (canonized under Uthman, by a committee headed by Muhammad's companions, with codices being produced and sent out to regional centers to replace any alternatives). Revisionists hold that canonization either happened later, or that it did not prevent substantial additional revisions afterwards. The skeptics ("de facto revisionists") are simply agnostic about the historicity of the traditional accounts. Neo-traditionalists accept the main details of the traditional account, but do so on the basis of critical historiography and not a trust of traditional sources.[13]

Recent radiocarbon, orthographic, and stemmatic analyses Quranic manuscripts converge on an early canonization event (during the reign of Uthman, as opposed to Abd al-Malik, the most commonly cited alternative)[14][15] and that copies of the canonized text were sent to Syria, Medina, Basra, and Kufa.[16]

In the decades after the canonization, a "rasm literature" emerged whereby authors sought to catalogue all variants that existed in copies or manuscripts of the Quran that descended from the Uthmanic standard. Among the most important of these include the Kitab al-Masahif by Abī Dāwūd (d. 929) the al-Muqni' fi Rasm al-Masahif by al-Dānī (d. 1052–1053). Such works, though, due to their lateness, do not reflect a number of the consistent variants in the earliest manuscripts.[17]

Readings (qirāʾāt)

[edit]Because the Uthmanic Quran did not standardize the dotting of the skeletal Arabic text (the rasm), variant ways to do this emerged in different cities. These different styles of dotting (and correspondingly, recitation) are called qirāʾāt ("readings"). Prominent reciters developed their own readings starting as early as the first half of the early 8th century. Ultimately, while many of these were created, only seven were canonized by Ibn Mujahid (d. 936) in the 10th century, these being known as the seven readers. Three readings were chosen from Kufa, and one each from Mecca, Medina, Basra, and Damascus. The reading of each teacher was independently attested through two transmissions, called a riwāyah (pl. riwāyāt), these typically being direct students. A century later, Al-Dani canonized two specific transmitters for each of the eponymous readers. In the 15th century, Ibn al-Jazari (d. 1429) canonized three more readers, giving us the modern ten recitations. Although variation between these is largely in the dotting, a few differences occur also with the rasm of Uthman, especially in Abu Amr's reading. Most variants only affect the form of the word, but a minority also impact the meaning. Common variants are dialectical, or concern noun formation, the singular versus plural, different verb stems, etc. Today, the reading of Hafs through Asim is the most popular in the Muslim world, having been canonized in the 1924 Cairo edition.[18][19]

Recent studies indicate that there is a common oral ancestor to all the canonical (and likely also non-canonical) readings that dates to the seventh century, after the reign of Uthman.[20]

Print editions

[edit]The Cairo edition, published in Egypt in 1924, is the dominant print edition of the Quran today. It follows the Hafs reading. Earlier but lesser-known print editions also once existed, including the Hinckelmann edition, Marracci edition, both from the late 17th century, and notably the Flugel edition, established in 1834 and remaining in use until the Cairo. Most physical copies of the Quran are high resolution prints of an originally handwritten Quran by a calligrapher, but this too is derived from the Cairo edition.[21] The orthography of the Cairo edition is largely faithful to what is found in seventh-century manuscripts, although not entirely:[22]

This is especially the case for the use of letter ʾalif, which is used to write the ā significantly more often in modern print editions than is typical for early manuscripts. But there are also several other innovative orthographic practices compared to early manuscripts. For example, the nominative pronoun ḏū is consistently spelled و ذ in modern print editions, while in early manuscripts it is consistently followed by an ʾalif, ا و ذ .

So far, no critical edition of the Quran exists. The creation of one is the major goal of the Corpus Coranicum project has, though so far, it has focused on publishing text editions of early manuscripts.[23]

Origins of the Quran

[edit]Geography

[edit]Outside the Hejaz

[edit]During the 1970s and 80s, several historians argued that the Quran originated beyond the Hejaz, if not the Arabian Peninsula.[24] The strongest justification that was seen for this was the view, by these authors (including John Wansbrough), that the Hejaz (if not Arabia) lacked the level of familiarity with Christian tradition that is displayed by the Quran. Instead, a more plausible provenance would be Mesopotamia or the Levant.[25] Wansbrough was followed by Gerald Hawting in his book The Idea of Idolatry and the Emergence of Islam,[26] although Fred Donner commented that Hawting did not provide any new evidence for this view.[27] Another work in this framework was Hagarism by Patricia Crone and Michael Cook, who kept the Quran in Arabia, but in its northwestern region instead of the Hejaz.[28] The most recent support has been from Stephen J. Shoemaker. Shoemaker places the life of Muhammad in the Hejaz, but positions the compilation of his oral teachings, including the redaction and editing of the Quran, in the Levant during the reign of the caliph Abd al-Malik.[29] Another proponent, Guillaume Dye, believes that the Quran represents a redaction of texts that would have emerged in different parts of Arabia, including but not limited to the Hejaz.[30]

Inside the Hejaz

[edit]The majority of historians accept a Hejazi origins of the Quran,[31] following a long standing consensus going back to Theodor Noldeke and his contemporaries through to W. Montgomery Watt before the rise of the revisionist school.[32] According to Angelika Neuwirth, the Hejazi position is supported by the latest manuscript, philological, and historical studies.[33]

Hejazi proponents argue that pre-Islamic Arabian Christianity was widespread enough to account for the Qurans familiarity with Christian tradition.[34] Hejazi proponents also question why a non-Hejazi origins of the Quran or Islam would be unanimously retrojected back into Mecca and Medina without trace of a competing or suppressed alternative or original view.[35] Taken further, this argument asserts that a non-Hejazi origins would require a conspiratorial level of forgery to maintain. Recent research has also established a major role played by Arabian tradition in the formation of the content of the Quran, such as the presence of Arabian words, Arabian prophets, etc.[36] Proponents also argue that all toponyms in the Quran are Hejazi, and that the Constitution of Medina (widely accepted as authentic) is also indicative of a Hejazi origins:[37]

It has often been noted that the Qur’an ‘has little concern with the proper names of its own place and time’ (Reynolds 2010: 198; see also Robin 2015a: 27–8), which, I think, makes it all the more significant that it does mention a handful of Ḥijāzī toponyms, including Badr (Q. 3:123), Ḥunayn (Q. 9:25), Yathrib (Q. 33:13), and Mecca (Q. 48:24)—this last notably in close conjunction with al-masjid al-ḥarām, ‘the sacred place of worship’, which appears in the following verse—as well as the tribe of Quraysh (Q. 106:1). Furthermore, the so-called ‘Constitution of Medina’, which is widely accepted as a genuinely early (i.e. start of the first-/seventh-century) document preserved in two third-/ninth-century Arabic works, does place a ‘Prophet’ (nabī) and a ‘Messenger of God’ (rasūl Allāh) called Muḥammad in a place called Yathrib (Lecker 2004).

Recent study of pre-Islamic Arabian inscriptions shows that the Arabic dialect of the Quran was a late-antique Hejazi.[38] It has also been shown that the spelling of the word Allah in the Quran is also specific to the dialect in the Hejazi.[39]

Authorship

[edit]There is no consensus on whether the Quran has one or more authors, with some scholars stressing the need for more research in the area.[40] The first study to evaluate this directly was by Behnam Sadeghi, who used stylometric analysis to argue for a single author.[41] Gabriel Said Reynolds argued for multiple authorship on the basis in his study on Quranic doublets, which he argued allows for the conclusion that two originally separate works, correlating to Meccan and Medinan surahs, were combined to form the Quran.[42][43] Tesei favors multiple authorship on the basis that there are two primary stylistic clusters of Quranic surahs,[40] corresponding mostly, but not exactly, to the division between Meccan and Medinan surahs.[44] Most recently, Michael Pregill has argued for three redactional layers of the Quran largely distinguished by their degree of familiarity with biblical and parabiblical tradition. For Pregill, Muhammad redacted/weaved these texts together to create the Quran.[45]

Historical context

[edit]The historical context of the Quran refers to the culture and societal milieu out of which the Quran emerged and may have been shaped by. The study of this context was a major area of research in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but experienced a half-century pause in engagement until the beginning of the 21st century.[46] Around this time, Christoph Luxenberg published his book The Syro-Aramaic Reading of the Koran, which asserted that the Quran originated as an Aramaic book in an Arabic-Aramaic bilingual environment.[47] His thesis was universally rejected.[48][49][50] Despite that, Luxenberg's resparked interest in the historical context of the Quran. Some of the leading scholars in this area now include Gabriel Said Reynolds, Holger Zellentin, Emran El-Badawi, and Joseph Witztum.[51] In terms of era, the Quran has been situated into the period of late antiquity (politically dominated by the Byzantine and Sasanian empires), and geographically, it has been situated as arising out of pre-Islamic Arabia.[52]

The context of the Quran has been independently studied, additionally, through the prism of a variety of linguistic and religious traditions.

Syriac

[edit]The Syriac Christian context has recently been one of the dominant paradigms of historical-context research.[53][54][55][56][57] Notable pre-Islamic Syriac authors analyzed in this context include Ephrem the Syrian, Jacob of Serugh, and Narsai. Joseph Witzum's dissertation, The Syriac Milieu of the Qurʾan: The Recasting of Biblical Narratives, is usually seen as the first major, serious publication in this area. Witzum's work is thought to have demonstrated that Syriac literature is crucial in reconstructing the context for Quranic narratives of the prophets.[58]

Rabbinic

[edit]The Quran refers twenty times to Jews (yahūd/allādhīna hādū), and also often refers to Israel or Israelites (banū isrāʾīl) and the People of Scripture (ahl al-kitāb). In addition, similarities between Quranic stories and motifs have regularly been observed with earlier rabbinic literature, especially in the Mishnah and Talmud, going back first to the studies of Abraham Geiger in the first half of the 19th century. The first major work in this regard was Geiger's 1833 Was hat Mohammed aus dem Judenthume aufgenommen?. The closest and most well-known intertext is that between Quran 5:32, which refers to a dictum that comes from the children of Israel, and Mishnah Sanhedrin 4:5 (in its form from the Palestinian Talmud).[45] Another oft-cited parallel is the tradition of raising a mountain above the Earth, found in both Quran 2:63 and the Babylonian Talmud (Shabbat 88a).[59] It has also been argued that the Quran responds in some instances to ideas found in rabbinic literature, such as the idea that an individual may only go to and remain in hell for a few days.[60] Legal continuity been the Quran and rabbinic texts has also been argued for in several instances.[61][62]

In understanding the conduit by which these stories may have appeared in the cultural milieu out of which the Quran emerged, many scholars have worked on understanding the spread of Judaism in pre-Islamic Arabia. A significant Jewish presence in South Arabia (Yemen) is known from the Himyarite Kingdom, as well as some evidence from the northern Hijaz, but inscriptional data from the central Hijaz (such as in Mecca and Medina) remains thin, although Islamic tradition and the Constitution of Medina both claim the presence of notable Jewish tribes in this region and time.[45]

Arabian

[edit]Recent years have seen a growth in the emphasis on considering the Quran in its pre-Islamic Arabian context, especially in light of the growth of archaeological discoveries from the region in recent years. One emphasis has been on the finding from the archaeological record, contrary to prior belief, that Judaism and Christianity in pre-Islamic Arabia were significantly more widespread than had been thought before, and that monotheism in pre-Islamic Arabia had become the dominant form of religious belief in the fifth and sixth centuries.[63][64] Asides from archaeology, similar observations have also been made regarding the representation of the "associationists" (mushrikūn) in the Quran, who though they provide intercessory prayer to intermediate beings, still believe in Allāh as the singular omnipotent Creator being[65][66] as well as Islamic-era collections of pre-Islamic poetry where there is a noted rarity of polytheistic invocations.[67]

Recent archaeological work has also resulted in many grammatical insights about the Quran, including demonstrations of how the spelling of some of the names of Quranic figures (like Jesus) are attested in Safaitic inscriptions[68] and how the Arabic of the Quran is in continuity with the late phase of pre-Islamic Arabic (known as Paleo-Arabic) in its Hijazi dialect.[38] Research has also investigated the continuity between Quranic ritual and ritual from pre-Islamic Arabia. For example, Arabic words for pilgrimage (ḥajj), prayer (ṣalāh), and charity (zakāh) are known from pre-Islamic Safaitic Arabic inscriptions.[69] In particular, both ḥajj and ʿumra have been argued to share many precise continuities with pre-Islamic Arabian ritual.[70] Pan-Arabian pilgrimage to the South Arabian Temple of Awwam has also been described.[70] Furthermore, it has been widely described that black stones believed to be of heavenly or meteorite origins were popularly used in Arabian cults.[71][72]

Greek

[edit]There is significant evidence of Hellenization in pre-Islamic Arabia, including in parts of the Hejaz.[73] Trends in Hellenization have concurrently been related to the Quran. In 2014, Omar Sankharé published what is still the only book-length investigation of the subject, in his volume Le Coran et la culture grecque. He studied the Quran vis-a-vis Greek literary descriptions of the flood, the legend of Korah, the triad of female intercessory beings mentioned in Quran 53:19–23, the story of Alexander the Great so-named as Dhu al-Qarnayn, the Surah of the Cave and Plato's Republic, and more.[74] Others have related Quranic to Hellenistic notions of time.[75] Individual studies have also focused on the following elements:

- Cole has demonstrated a notable overlap between Quranic law, like Surah Al-Ma'idah (5), and late Roman law, like the Corpus Juris Civilis codified during the reign of Justinian I.[73][76]

- Expressions such as being "dyed by the dye of God" (Quran 2:138) also echoes a widespread phrase, found from the Republic to late antiquity.[77]

- The story of Jesus' birth in relation to the palm tree has also been related to a tradition witnessed in the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, ultimately going back further still to a reworking of traditions surrounding Leto's labor.[78][79]

- The figure of Luqman in Quran 31 has been related by some to the Greek philosopher Alcmaeon of Croton.[77]

- Quran 52:24 has been related by Walid Saleh to Ganymede.[80]

Jewish Christian

[edit]It has long been argued that Jewish Christianity played an important role in the formation of Quranic conceptions of Christians in Muhammad's Arabia.[81][82] The first major argument put forwards that Jewish Christianity played an important role in the formation of Quranic tradition was Aloys Sprenger in his 1861 book Das Leben und die Lehre des Moḥammad. Since then, numerous other authors have followed this argument, including Adolf von Harnack, Hans-Joachim Schoeps, M. P. Roncaglia, and others.[83] The most recent notable defenders of this thesis have been Francois de Blois[84] and Holger Zellentin, the latter in the context of his research into the historical context of the legal discourses present in the Quran especially as it resembles the Syriac recension of the Didascalia Apostolorum and the Clementine literature.[85] In turn, several critics of this thesis have appeared, most notably Sidney Griffith.[86][87] De Blois provides three arguments for the importance of Jewish Christianity: the use of the term naṣārā in the Quran (usually taken as a reference to Christians, as in Griffith's work) which resembles the Syriac term used for Nazoreans, the resemblance between the description of Mary as part of the Trinity with traditions attributed to the Gospel of the Hebrews, and dietary restrictions associated with the Christian community. In turn, Shaddel argued that naṣārā merely may have etymologically originated as such because Nazoreans were the first to interact with the Arabic community in which this term came into use. Alternative sources as well as hyperbole may explain the reference to Mary in the Trinity. However, Shaddel does admit the ritual laws as evidence for the relevance of Jewish Christians.[88] In the last few years, the thesis for the specific role played by Jewish Christians has been resisted by Gabriel Said Reynolds,[89][90] Stephen Shoemaker,[91] and Guillaume Dye.[92]

History of the field

[edit]Premodern predecessors

[edit]While formal works on Quranic studies had not emerged until multiple centuries after the death of Muhammad, key topics were addressed within other disciplines earlier own. Early exegetical works (tafsīr) included discussions on asbāb al-nuzūl (occasions of authorship), qirāʾāt (readings), and linguistic nuances. Jurists incorporated interpretations of Qurʾānic verses into legal reasoning, while grammarians analyzed the text for its syntactic and phonological features.[93]

By the 10th century, early independent treatises began addressing the sciences of the Qurʾān. Figures like Muḥammad ibn Khalaf al-Marzubān (al-Ḥāwī fī ʿUlūm al-Qurʾān) and others compiled extensive discussions on topics such as abrogation, ambiguous verses, and linguistic peculiarities. These works were often encyclopedic however, incorporating earlier scholarship and organizing it into coherent frameworks.[94]

Al-Suyūṭī’s al-Itqān fī ʿUlūm al-Qurʾān expanded on al-Zarkashī’s framework, identifying 80 sciences and incorporating discussions on previously neglected areas. Al-Suyūṭī emphasized the interdisciplinary nature of Qurʾānic studies, linking linguistic analysis, legal theory, and spiritual reflection. His work became a cornerstone of Arabic-language Quranic studies literature.[95]

Modern Quranic studies

[edit]The modern discipline of studying the Quran may be considered to have begun in 1833, with the publication of the book Was hat Mohammed aus dem Judenthume aufgenommen? (‘What Did Muhammad Take Over from Judaism?’) by Abraham Geiger. The primary objective of this book was to demonstrate that the Quranic reception of biblical narratives did not occur directly via a reception of the books of the canonical Bible, but through parabiblical intermediaries such as midrash (traditional Jewish exegesis of biblical texts). Geiger, being a rabbinic scholar, focused on the Qurans correspondence with the Jewish literary tradition. This approach continued in the works of Hartwig Hirschfeld, Israel Schapiro, and others, before finally culminating in Heinrich Speyer's Die biblischen Erzählungen im Qoran, published in 1931. This mode of scholarship however came to an end with World War II, when a mass of Jewish academics were dispersed from Nazi Germany, and the primary contributors transitioned to working in adjacent areas of research. During this period, a different but smaller school of research emphasizing the influence of Christian texts (prominently including Tor Andrae); while research on pagan influences was not entirely absent from this time, it was comparatively severely understudied.[5] In recent years, a trend that has been called the "New Biblicism" or "Syriac Turn" of Quranic studies has emerged, refocusing on the intertextuality of the Quran with a much greater attention paid to Christian intertexts. The current paradigm of research was initiated by Christoph Luxenberg; though his thesis was universally rejected among academics, it generated considerable new interest in studying the Quran in light of its historical context. The primary historians of this new wave of scholarship have included Gabriel Said Reynolds, Holger Michael Zellentin, Emran El-Badawi, and Joseph Witztum.[51]

In 1844, Gustav Weil published the first critical introduction to the Quran in Europe, with a second edition in 1878. The work was titled Einleitung in den Koran. This work succeeded an earlier book three-part book of his which treated the subjects of Muhammad, the Quran, and then Islam. In 1858, French Académie des Inscriptions announced a European-wide competition for a work on the history of the Quran. Three people jointly won: Theodor Noldeke, Aloys Sprenger, and Michele Amari. While Amari's work was never published, that of Sprenger and Amari would become foundational publications in the emerging field of Quranic studies.[96]

In 1860, Noldeke published his thesis as a book titled Geschichte des Qorans (History of the Quran). Subsequent editions of the book were published by Friedrich Schwally, Gotthelf Bergsträsser, and Otto Pretzl between 1909 and 1938. This work had a major influence and, for a significant time, resulted in a consensus among Western scholars that the Quran reflected the preaching of Muhammad in Mecca and Medina, and that it should be chronologically periodized into four main types of surahs: Meccan surahs, which were divided into Early Meccan, Middle Meccan, and Late Meccan surahs, followed by Medinan surahs. Noldeke also accepted a canonization event during the reign of the third caliph, Uthman. (These views have been categorized by some as the "Noldekian paradigm". One of the first to question this paradigm was Hartwig Hirschfeld in his 1902 work New researches into the composition and exegesis of the Qoran.) As for Sprenger, his work was published in 1861–65 in three volumes under the title Das Leben und die Lehre des Mohammad, nach bisher größtenteils unbenutzten Quellen. Both Noldeke and Sprenger owed much to the Al-Itqan fi Ulum al-Qur'an of Al-Suyuti which had summarized hundreds of works of the medieval Islamic tradition.[96] Other important publications from this early time included the Die Richtungen der Islamischen Koranauslegung of Ignaz Goldziher, which founded the critical study of the tafsir (commentary, exegesis) of the Quran and the Materials For The History Of The Text Of The Quran The Old Codices by Arthur Jeffrey in 1934.[97]

After WW2

[edit]After World War II, there was no primary locus for the study of the Quran. The major scholars from this time period, including Arthur Jeffrey, W. Montgomery Watt, William Graham, Rudi Paret, and others, thought it best to treat the Quran as Muslims do (as sacred) and so avoided discussion of its relationship with earlier Jewish and Christian literature. In light of this, decrials of research that focused on the origins of the Quran, efforts towards promoting Christian-Muslim dialogue, the move to read the Quran in light of traditional exegesis instead of earlier tradition, the disbandment of the primary locus of Quranic research in Germany after the war, and other reasons, the study of the historical context of the Quran would descend into obscurity for the remainder of the twentieth century, until being revived by the turn of the twenty-first century.[46]

During this period, many works from this time sought to foster good relations with Muslims; for example, Johann Fück wrote works about the originality of Muhammad. In addition, growing attention was paid to the tafsir (in which important progress was made) in part to avoid thorny critical issues surrounding the Quran and Muhammad. This continued well into the twentieth century, the latter period of which was best characterized by the works of Andrew Rippin, Jane McAullife, and Brannon Wheeler (as in his book Moses in the Quran and Islamic Exegesis).[98] Books that critically appraised traditional sources concerning the origins of the Quran only began to appear in the 1970s, starting with the revisionist writings of Günter Lüling (1974), John Wansbrough (1977), and Patricia Crone and Michael Cook (1977). Though the theses advanced in these books were rejected, they resulted in a considerable diversity of new perspectives and analyses.[99]

The present phase of Quranic studies began in the 1990s and, since then, the field has witnessed an explosion of interest and popularity.[4] This has coincided with the formation of new journals such as the Journal of Qur'anic Studies, societies such as the International Qur'anic Studies Association (IQSA), and the publication of major resources like The Encyclopaedia of the Quran (2001–6). 2007 saw the initiation of the Corpus Coranicum project, led by Angelika Neuwirth, Nicolai Sinai, among others. In 2015, the publication of the Study Quran by HarperCollins included an English translation of the text, accompanied by a massive collection of traditional interpretations for each verse from a total of several dozen Islamic exegetes.[100]

Despite the progress, there is still significant work to do in the field. For example, a critical edition of the Quran, which has been available for the Bible for decades, is still unavailable, despite an effort towards producing one in the first half of the twentieth century that was cut short by the second world war.[101] Only one critical translation of the Quran has so far been published, by Arthur Droge in 2014.[102][103]

Notable publications

[edit]- The Foreign Vocabulary of the Qur'an, 1938

- A Concordance of the Qurʾān, 1983.

- Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān, Vols 1–5, 2001–2006

- A Concise Dictionary of Koranic Arabic, 2004

- The Integrated Encyclopedia of the Qurʾān (IEQ) by the Center for Islamic Sciences[104]

- The Qur'an: An Encyclopedia, 2006

- The Cambridge Companion to the Qur'an, 2006

- Dictionnaire du Coran, 2007

- The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to the Qur’an, 2017

- The Qur’an: A Historical-Critical Introduction, 2018

- The Oxford Handbook of Qur'anic Studies, 2020

- The Routledge Companion to the Qur'an, 2021

- Key Terms of the Qur'an, 2023

Commentaries

[edit]English

[edit]- Azaiez, Mehdi et al. The Qur'an Seminar Commentary / Le Qur'an Seminar, De Gruyter 2016.

- Bell, Richard. A Commentary on the Quran, Vols 1–2, 1991.

- Nasr, Seyyed et al. The Study Quran: A New Translation and Commentary, HarperCollins 2015.

- Neuwirth, Angelika. The Qur'an: Text and Commentary. Volume 1, Early Meccan Surahs: Poetic Prophecy, Oxford University Press 2022.

- Reynolds, Gabriel Said. The Qur'an and the Bible: Text and Commentary, Yale University Press 2018.

- Sirry, Mun'im. The Quran with Cross-References, De Gruyter 2022.

German

[edit]- Khoury, Adel Theodor. Der Koran. Arabisch-Deutsch. Übersetzung und wissenschaftlicher Kommentar, 2001.

- Neuwirth, Angelika:

- Bd. 1: Frühmekkanische Suren, 2011.

- Bd. 2/1: Frühmittelmekkanische Suren, 2017.

- Bd. 2/2: Spätmittelmekkanische Suren, 2021.

- Paret, Rudi. Der Koran, Kommentar und Konkordanz, 1963.

French

[edit]- Azaiez, Mehdi et al. The Qur'an Seminar Commentary / Le Qur'an Seminar, De Gruyter 2016.

- Dye, Guillaume & Mohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi. Le Coran des historiens, Vols 1–3, Éditions du Cerf 2019.

Academic journals

[edit]- Arabica[105]

- Der Islam

- Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam[106]

- Journal of Qur'anic Studies

- Journal of the International Qur’anic Studies Association (JIQSA)[107]

See also

[edit]- Hadith studies

- Historiography of early Islam

- History of the Quran

- Islamic studies

- Quranic cosmology

- Quranic counter-discourse

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Sinai 2017, p. 2–5.

- ^ Sinai 2015.

- ^ Sinai 2020.

- ^ a b Zadeh 2015.

- ^ a b Stewart 2017, p. 9–10.

- ^ Stewart 2017, p. 7.

- ^ Van Putten 2024, p. 152.

- ^ Deroche 2022, p. 121–129.

- ^ Anthony 2019.

- ^ Van Putten 2024, p. 162.

- ^ Deroche 2022, p. 136.

- ^ Sadeghi & Goudarzi 2012, pp. 1–4.

- ^ Sadeghi & Goudarzi 2012, p. 4.

- ^ Van Putten 2024, p. 153–157.

- ^ Van Putten 2019.

- ^ Sidky 2020.

- ^ Van Putten 2024, p. 155.

- ^ Van Putten 2024, p. 155–161.

- ^ Van Putten 2022.

- ^ Sidky 2023.

- ^ Van Putten 2024, p. 162–166.

- ^ Van Putten 2024, p. 166.

- ^ Van Putten 2024, p. 166–167.

- ^ Sirry 2021, p. 121–123.

- ^ Wansbrough 1977, p. 34, 50.

- ^ Hawting 1999.

- ^ Donner 2011, p. 29.

- ^ Crone & Cook 1977.

- ^ Shoemaker 2022.

- ^ Dye 2023.

- ^ Tesei 2021, p. 188.

- ^ Sirry 2021, p. 118–119.

- ^ Neuwirth 2017, p. 152.

- ^ Sinai 2024.

- ^ Sirry 2021, p. 123–124.

- ^ Dost 2017.

- ^ Munt 2020, p. 100.

- ^ a b Van Putten 2023.

- ^ Al-Jallad & Sidky 2024, p. 6.

- ^ a b Tesei 2021.

- ^ Sadeghi 2011.

- ^ Reynolds 2021.

- ^ Reynolds 2022.

- ^ Sinai 2023, p. XIV.

- ^ a b c Pregill 2023.

- ^ a b Stewart 2024.

- ^ Sirry 2021, p. 111.

- ^ Neuwirth 2019, p. 50–51.

- ^ Witzum 2011, p. 51–53, esp. n. 193.

- ^ Zellentin 2019.

- ^ a b Stewart 2017, p. 20–28.

- ^ Dye, Guillaume, ed. (2022). Early Islam: the sectarian milieu of late antiquity?. Problèmes d'histoire des religions. Brussels: Éditions de l'Université de Bruxelles. ISBN 978-2-8004-1814-8. OCLC 1371946542.

- ^ Reynolds 2010.

- ^ Reynolds 2018.

- ^ Van Bladel 2008.

- ^ Griffith 2008.

- ^ Witzum 2009.

- ^ Rizk 2023, p. 33–35.

- ^ Reynolds 2018, p. 50–51.

- ^ Mazuz 2014, p. 70–72.

- ^ Powers 2020, p. 19–21.

- ^ Hussain 2021, p. 89–91.

- ^ Al-Jallad & Sidky 2021.

- ^ Lindstedt 2023.

- ^ Crone 2012.

- ^ Crone 2013.

- ^ Sinai 2019.

- ^ Al-Jallad & Al-Manaser 2021.

- ^ Al-Jallad 2022, p. 41–44, 68.

- ^ a b Dost 2023.

- ^ Wheeler 2006, p. 28–29.

- ^ Hoyland 2001, p. 183.

- ^ a b Cole 2020.

- ^ Sankharé 2014.

- ^ Tamer 2011.

- ^ Cole 2022.

- ^ a b Cole 2021.

- ^ Mourad 2002.

- ^ Neuwirth 2019, p. 298.

- ^ Saleh 2009.

- ^ Strousma 2015, p. 138–158.

- ^ Sánchez 2021.

- ^ Crone 2015, p. 227–228.

- ^ De Blois 2002.

- ^ Zellentin 2013.

- ^ Crone 2015, p. 228.

- ^ Griffith 2011.

- ^ Shaddel 2016, p. 21–31.

- ^ Reynolds 2014.

- ^ Reynolds 2019.

- ^ Shoemaker 2018.

- ^ Dye 2021, p. 158–162.

- ^ "Mabahith fi 'ulum al-Quran". sites.dlib.nyu.edu. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ Marketing Communications: Web | University of Notre Dame. "The Quran in Its Historical Context | Department of Theology | University of Notre Dame". Department of Theology. Archived from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ Suyūṭī. Kitāb al-itqān fī ʻulūm al-Qurʼān lil-Shaykh al-Imām al-ʻĀlim al-ʻAllāmah Jalāl al-Dīn al-Asyūṭī (in Arabic). Library of Congress.

- ^ a b Stewart 2017, p. 10–12.

- ^ Jeffrey 1937.

- ^ Stewart 2017, p. 14–16.

- ^ Donner 2008, p. 29–31.

- ^ Stewart 2017, p. 19–20.

- ^ Reynolds 2008, p. 1–6.

- ^ Droge 2013.

- ^ Oliver 2023, p. 218.

- ^ "IEQ". Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ "Arabica". Brill. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ "Jerusalem studies in Arabic and Islam". Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ "IQSA". Retrieved 3 April 2020.

Sources

[edit]- Al-Jallad, Ahmad (2022). The Religion and Rituals of the Nomads of Pre-Islamic Arabia: A Reconstruction Based on the Safaitic Inscriptions. Brill.

- Al-Jallad, Ahmad; Al-Manaser, Ali (2021). "The Pre-Islamic Divine Name ʿsy and the Background of the Qurʾānic Jesus". Journal of the International Qur'anic Studies Association. 6 (1): 107–136. doi:10.5913/jiqsa.6.2021.a004.

- Al-Jallad, Ahmad; Sidky, Hythem (2021). "A Paleo-Arabic inscription on a route north of Ṭāʾif". Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 33 (1): 1–14.

- Al-Jallad, Ahmad; Sidky, Hythem (2024). "A Paleo-Arabic Inscription of a Companion of Muhammad?". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 83 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1086/729531.

- Anthony, Sean (2019). "Two 'Lost' Sūras of the Qurʾān: Sūrat al-Khalʿ and Sūrat al-Ḥafd between Textual and Ritual Canon (1st -3rd/7th -9th Centuries)". Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam. 46: 67–112.

- Cole, Juan (2020). "Muhammad and Justinian: Roman Legal Traditions and the Qurʾān". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 79 (2): 183–196. doi:10.1086/710188.

- Cole, Juan (2021). "Dyed in Virtue: The Qur'ān and Plato's Republic". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. 61: 580–604.

- Cole, Juan (2022). "Late Roman Law and the Quranic Punishments for Adultery". The Muslim World. 112 (2): 207–224. doi:10.1111/muwo.12436. hdl:2027.42/174954.

- Crone, Patricia; Cook, Michael (1977). Hagarism: The Making of the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press.

- Crone, Patricia (2012). "The Quranic Mushrikūn and the resurrection (Part I)". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 75 (3): 445–472. doi:10.1017/S0041977X12000584. JSTOR 41811204.

- Crone, Patricia (2013). "The Quranic Mushrikūn and the resurrection (Part II)". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 76 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1017/S0041977X12000596. JSTOR 41811251.

- Crone, Patricia (2015). "Jewish Christianity and the Qurʾān (Part One)". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 74 (2): 225–253. doi:10.1086/682212. JSTOR 10.1086/682212.

- De Blois, François (2002). "Naṣrānī (Ναζωραȋος) and ḥanīf (ἐθνικός): Studies on the Religious Vocabulary of Christianity and of Islam". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 65 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1017/S0041977X02000010. JSTOR 4145899.

- Deroche, Francois (2022). The One and the Many: The Early History of the Qur'an. Yale University Press.

- Donner, Fred (2008). "The Qurʾān in Recent Scholarship: Challenges and desiderata". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Qurʾān in its Historical Context. Routledge. pp. 29–50.

- Donner, Fred (2011). "The Historian, the Believer, and the Qurʾān". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). New Perspectives on the Qur'an: The Qur'Ɨn in Its Historical Context 2. Routledge.

- Dost, Suleyman (2017). An Arabian Qur'ān: Towards a Theory of Peninsular Origins.

- Dost, Suleyman (2023). "Pilgrimage in Pre-Islamic Arabia: Continuity and Rupture from Epigraphic Texts to the Qur'an". Millennium. 20 (1): 15–32. doi:10.1515/mill-2023-0003.

- Droge, Arthur (2013). The Qur'an: A New Annotated Translation. Equinox.

- Dye, Guillaume (2021). "Mapping the Sources of the Qur'anic Jesus". In Mortensen, Mette Bjerregaard; Dye, Guillaume; Oliver, Isaac W.; Tesei, Tommaso (eds.). The Study of Islamic Origins: New Perspectives and Contexts. De Gruyter.

- Dye, Guillaume (2023). "Ǫuelques questions sur les contextes du Coran". Archimède. 10 (1): 22–33. doi:10.47245/archimede.0010.ds1.02.

- Griffith, Sidney (2008). "Christian lore and the Arabic Qur'an: the "Companions of the Cave" in Surat al-Kahf and in Syriac Christian tradition". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Qurʾān in its Historical Context. Routledge.

- Griffith, Sidney (2011). "Al-Naṣārā in the Qurʾān: A hermeneutical reflection". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). New Perspectives on the Qur'an: The Qur'an in its Historical Context 2. Routledge. pp. 301–322.

- Hawting, Gerald (1999). The Idea of Idolatry and the Emergence of Islam: From Polemic to History. Cambridge University Press.

- Hoyland, Robert (2001). Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam. Routledge.

- Hussain, Saqib (2021). "The Bitter Lot of the Rebellious Wife: Hierarchy, Obedience, and Punishment in Q. 4:34". Journal of Qur'anic Studies. 23 (2): 66–111. doi:10.3366/jqs.2021.0466.

- Jeffrey, Arthur (1937). Materials For The History Of The Text Of The Quran The Old Codices. Brill.

- Lindstedt, Ilkka (2023). Muhammad and His Followers in Context: The Religious Map of Late Antique Arabia. Brill.

- Mazuz, Haggai (2014). The Religious and Spiritual Life of the Jews of Medina. Brill.

- Mourad, Suleiman (2002). "From Hellenism to Christianity and Islam: The Origin of the Palm tree Story concerning Mary and Jesus in the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew and the Qurʾān" (PDF). Oriens Christianus. 86: 206–216.

- Munt, Harry (2020). "The Arabian Context of the Qur'an: History and the Text". In Shah, Mustafa; Haleem, M.A.S. Abdel (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Qur'anic Studies. Oxford University Press.

- Neuwirth, Angelika (2017). "Structure and the Emergence of Community". In Rippin, Andrew; Mojaddedi, Jawid (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Companion to the Qurʾān. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 151–170.

- Neuwirth, Angelika (2019). The Qur'an and Late Antiquity: A Shared Heritage. Oxford University Press.

- Oliver, Isaac (2023). "The Historical-Critical Study of Jewish, Christian, and Islamic Scriptures". In Dye, Guillaume (ed.). Early Islam: The Sectarian Milieu of Late Antiquity?. Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles.

- Powers, David (2020). "The Qurʾān and its Legal Environment". In Daneshgar, Majid; Hughes, Aaron W. (eds.). Deconstructing Islamic Studies. Harvard University Press. pp. 9–32.

- Pregill, Michael (2023). "From the Mishnah to Muḥammad: Jewish Traditions of Late Antiquity and the Composition of the Qur'an". Studies in Late Antiquity. 7 (4): 516–560. doi:10.1525/sla.2023.7.4.516.

- Reynolds, Gabriel Said (2008). "Introduction: Qur'anic studies and its controversies". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Qurʾān in its Historical Context. Routledge. pp. 1–26.

- Reynolds, Gabriel Said (2010). The Qur'an and its Biblical Subtext. Routledge.

- Reynolds, Gabriel Said (2014). "On the Presentation of Christianity in the Qura'n and the Many Aspects of Qur'anic Rhetoric" (PDF). Al-Bayan Journal of Qur'an and Hadith Studies. 12 (1): 42–54. doi:10.1163/22321969-12340003.

- Reynolds, Gabriel Said (2018). The Qur'an and the Bible: Text and Commentary. Yale University Press.

- Reynolds, Gabriel Said (2019). "On the Qur'an and Christian heresies". The Qur'an's Reformation of Judaism and Christianity: Return to the Origins. Routledge.

- Reynolds, Gabriel Said (2021). "The Qur'ānic Doublets: A Preliminary Inquiry". Journal of the International Qur'anic Studies Association. 5 (1): 5–40. doi:10.5913/jiqsa.5.2020.a001.

- Reynolds, Gabriel Said (2022). "Intratextuality, Doublets, and Orality in the Qur'an, with Attention to Suras 61 and 66". In Sinai, Nicolai (ed.). Unlocking the Medinan Qur'an. Brill. pp. 513–542.

- Rizk, Charbel (2023). Prophetology, Typology, And Christology: A New Reading Of The Quranic Joseph Story In Light Of The Syriac Tradition.

- Sadeghi, Behnam (2011). "The Chronology of the Qurān: A Stylometric Research Program". Arabica. 58 (3–4): 210–299. doi:10.1163/157005810X529692.

- Sadeghi, Behnam; Goudarzi, Mohsen (2012). "Ṣan'ā' and the Origins of the Qur'ān". Der Islam. 87 (1–2): 1–129. doi:10.1515/islam-2011-0025.

- Saleh, Walid (2009). "The Etymological Fallacy And Qur'Anic Studies: Muhammad, Paradise, And Late Antiquity". In Neuwirth, Angelika; Sinai, Nicolai; Marx, Michael (eds.). The Qurʾān in Context. Brill. pp. 649–698.

- Sánchez, Francisco F. del Río (2021). "The Deadlocked Debate about the Role of the Jewish Christians at the Birth of Islam". Religions. 12 (10).

- Sankharé, Omar (2014). Le Coran et la culture grecque. Editions L'Harmattan.

- Sidky, Hythem (2020). "On the Regionality of Qurʾānic Codices". Journal of the International Qur'anic Studies Association. 5: 133–210. doi:10.5913/jiqsa.5.2020.a005.

- Sidky, Hythem (2023). "Consonantal Dotting and the Oral Quran". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 143 (4): 785–814. doi:10.7817/jaos.143.4.2023.ar029.

- Sinai, Nicolai (2015). "Historical-Critical Readings of the Abrahamic Scriptures". In Silverstein, Adam J.; Strousma, Guy G. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Abrahamic Religions. Oxford University Press. pp. 208–225.

- Sinai, Nicolai (2017). The Qurʾan: A Historical-Critical Introduction. Edinburgh University Press.

- Sinai, Nicolai (2019). Rain-giver, bone-breaker, score-settler: allāh in Pre-Quranic poetry. Lockwood Press.

- Sinai, Nicolai (2020). "Historical Criticism and Recent Trends in Western Scholarship on the Qur'an: Some Hermeneutic Reflections". Journal of College Sharia & Islamic Studies. 38 (1): 136–146. doi:10.29117/jcsis.2020.0259. hdl:10576/15058.

- Sinai, Nicolai (2023). Key Terms of the Qur'an: A Critical Dictionary. Princeton University Press.

- Sinai, Nicolai (2024). "The Christian Elephant in the Meccan Room: Dye, Tesei, and Shoemaker on the Date of the Qurʾān". Journal of the International Qur'anic Studies Association. 9: 1–46. doi:10.1515/jiqsa-2023-0013.

- Sirry, Mun'im (2021). Controversies over Islamic Origins: An Introduction to Traditionalism and Revisionism. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Shaddel, Mehdy (2016). "Qurʾānic ummī: Genealogy, Ethnicity, and the Foundation of a New Community". Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam. 43: 1–60.

- Shoemaker, Stephen (2018). "Jewish Christianity, Non-Trinitarianism and the Beginnings of Islam". In Mimouni, Simon (ed.). Judaïsme ancien et origines du christianisme. Brepols. pp. 105–116.

- Shoemaker, Stephen (2022). Creating the Qur'an: A Historical-Critical Study. University of California Press.

- Stewart, Devin (2017). "Reflections on the State of the Art in Western Qurʾanic Studies". In Bakhos, Carol; Cook, Michael (eds.). Islam and Its Past: Jahiliyya, Late Antiquity, and the Qurʾan. Oxford University Press. pp. 4–68.

- Stewart, Devin (2024). "Ignoring the Bible in Qur'anic Studies: Scholarship of the Late Twentieth Century". ReOrient. 9 (1): 131–169.

- Strousma, Guy (2015). The Making of the Abrahamic Religions in Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press.

- Tamer, Georges (2011). "Hellenistic Ideas of Time in the Koran". In Gall, Lothar; Willoweit, Dietmar (eds.). Judaism, Christianity, and Islam in the Course of History: Exchange and Conflicts. De Gruyter. pp. 21–41.

- Tesei, Tommaso (2021). "The Qur'an(s) in Context(s)". Journal Asiatique. 309 (2): 185–202.

- Van Bladel, Kevin (2008). "The Alexander Legend in the Qur'an 18:83-102". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Qurʼān in Its Historical Context. Routledge.

- Van Putten, Marijn (2019). ""The Grace of God" as evidence for a written Uthmanic archetype: the importance of shared orthographic idiosyncrasies". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 82 (2): 271–288. doi:10.1017/S0041977X19000338. hdl:1887/79373.

- Van Putten, Marijn (2022). "When the Readers Break the Rules: Disagreement with the Consonantal Text in the Canonical Quranic Reading Traditions". Dead Sea Discoveries. 29 (3): 438–462. doi:10.1163/15685179-02903008. hdl:1887/3619266.

- Van Putten, Marijn (2023). "The Development of the Hijazi Orthography". Millennium. 20 (1): 107–128. doi:10.1515/mill-2023-0007. hdl:1887/3715910.

- Van Putten, Marijn (2024). "Textual Criticism of the Quran". In Finsterbusch, Karin; Fuller, Russell; Lange, Armin; Driesbach, Jason (eds.). The Comparative Textual Criticism of Religious Scriptures. Brill. pp. 152–172. doi:10.1163/9789004693623_009. ISBN 978-90-04-69362-3.

- Wansbrough, John (1977). Qur'anic Studies: Sources and Methods of Scriptural Interpretation. Prometheus.

- Witzum, Joseph (2009). "The foundations of the house (Q 2: 127)". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 72 (1): 25–40. doi:10.1017/S0041977X09000020.

- Witzum, Joseph (2011). The Syriac Milieu of the Quran.

- Wheeler, Brannon (2006). Mecca and Eden: Ritual, Relics, and Territory in Islam. University of Chicago Press.

- Zadeh, Travis (2015). "Quranic Studies and the Literary Turn". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 135 (2): 329–342. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.135.2.329. JSTOR 10.7817/jameroriesoci.135.2.329.

- Zellentin, Holger (2013). The Qur ͗ān's legal culture: the "Didascalia Apostolorum" as a point of departure. Mohr Siebeck.

- Zellentin, Holger (2019). "The Qur'an and the Reformation of Judaism and Christianity". In Zellentin, Holger (ed.). The Qur'an's Reformation of Judaism and Christianity: Return to the Origins. Routledge.