Communion (chant)

The Communion (Latin: communio; Ancient Greek: κοινωνικόν, koinonikon) is a refrain sung with psalm recitation during the distribution of the Eucharist in the Divine Liturgy or Mass. As chant it was connected with the ritual act of Christian communion.

The koinonikon cycle of the Divine Liturgy in Orthodox rites

[edit]According to Dimitri Conomos the koinonikon (κοινωνικόν), as it is sung as an elaborated communion chant during the Divine Liturgy, has derived from an early practice of psalm recitation similar to Western liturgies, when the Koinonikon served as a troparion.[1] The oldest troparion which was used for communion, was "Γεύσασθε καὶ ἴδετε" ("O taste and see that the Lord is good", Ps. 33:9). It was supposed to symbolize the last supper celebrated on Maundy Thursday. During the 5th century, when the Divine Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts had established and this communion chant became associated with it, the custom spread over the Lenten period, presumably with the recitation of different psalm sections (staseis).

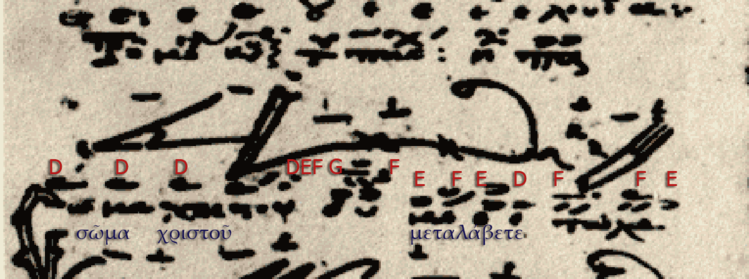

In the early Asmatika (12th and 13th century), the choirbook of the cathedral rite, this koinonikon is classified as echos protos (transcribed as a—α′) according to the modal signatures of the Octoechos, but its archaic melos does not finish on the finalis and basis of this echos, but with the one (phthongos) of echos plagios devteros (transcribed as E—πλβ′).[2]

The koinonikon cycles of the Byzantine cathedral rite

[edit]In the cathedral rite of Constantinople the koinonikon as a troparion became so elaborated, that it was sung without psalm recitation.

Nevertheless, its text was usually a stichos taken from the psalter, like the Sunday Koinonikon of the Week Cycle Αἰνεῖτε τὸν κύριον ("Praise the Lord" Ps 148:1), which had already added as an Octoechos cycle in 13th-century Greek Asmatika, so that they could be performed according to the echos of the week.[3] Within the weekly cycle each koinonikon was also specified to certain liturgical occasions such as the Wednesday koinonikon Ποτήριον σωτηρίου ("Cup of salvation" Ps 115:4) which was dedicated to feasts around the Theotokos or around martyres. Apart from the week cycle there was a repertory of 26 koinonika which developed as a calendaric cycle of immoveable and moveable feasts during the 9th century and they can be found in the books of the cathedral rite since the 12th century (psaltikon and asmatikon).[4]

Since the 14th century, when a mixed rite had replaced the former tradition of the cathedral rite at Hagia Sophia, the old models have been elaborated in compositions of the Maistores like John Glykys, John Koukouzeles, and Manuel Chrysaphes.

Communion chant in Western plainchant

[edit]The communio part of the Ambrosian mass

[edit]The communion part of the Ambrosian Mass, as it had been celebrated in the cathedrals of Milan (called after the famous local bishop Ambrose), was composed around the Anaphora. It was opened by a litany called "Ter Kyrie", the Pater Noster, and the chant which preceded the Postcommunio, was called "Transitorium".

The confractorium of the Gallican and Visigothic mass

[edit]According to Isidore of Seville (Etymologiae, De ecclesiasticis officiis) and Pseudo-Germanus' Expositio Antiquae Liturgiae Gallicanae[5] the communion chant of the Mass in the Gallican rite of France and the Visigothic rite of Spain was called Confractorium and probably connected with a ritual breaking (fraction) of sacramental bread.

The communion cycle of the Roman and Roman-Frankish rite

[edit]According to James McKinnon the communio became late part of Roman Mass, and like in many other Western sources, there is no early evidence of a Latin equivalent of the Ps. 33:9 ("Gustate et videte") as a kind of prototype of the genre, but Ordo romanus I describes the communion chant as an antiphon with psalm sung by the Schola cantorum accompanying the distribution of the Eucharist, until the presiding pope interrupts it.[6] Nevertheless, the genre communio became an important and favored subject in the process of a compositional planning of the Mass Proper by the leader of the Schola cantorum, which had already about 141 items during the 7th century. The dramaturgy in the composition of communion chants and the choice of scriptural texts from Advent to Epiphany includes the composition of an epic recitation of prophetic texts before Christmas, while the later serial of communion chants use extracts from the gospel readings of the day, composed in a rather dramatic style.[7]

Since the Carolingian reform the Roman Mass Proper became part of the Roman-Frankish liturgy and the most common musical settings of it were reserved for special Masses such as Requiem Masses, where the chant has the incipit Lux aeterna.

In contemporary Catholic usage, the communion chant corresponds to the Communion Antiphon and is sung or recited audibly throughout by the faithful.

See also

[edit]- Ambrosian chant

- Anaphora

- Byzantine chant

- Eucharist

- Fraction

- Gallican chant

- Gregorian Chant

- Mass

- Mozarabic chant

- Old Roman Chant

- Roman rite

- Sacramental bread

- Schola cantorum

References and sources

[edit]- ^ Dimitri Conomos (1985).

- ^ See transcription of Ms. Γ. 3 (fol. 9)—an Asmatikon of the Great Lavra Monastery on Mount Athos (Conomos 1980, p. 259, ex. 4).

- ^ Conomos (1980, pp. 255-259, ex. 2) analyzed this cycle, added later during the late 14th century, and compared it to the earlier echos-protos version in a Slavic Kondakar of the 13th century (ex. 3).

- ^ In his early article which preceded his book, Dimitri Conomos (1980) offers tables of the three cycles, their texts and their modal classification according to the Octoechos and a list of medieval notated chant manuscripts of the cathedral rite which have preserve these cycles.

- ^ Autun, Bibliothèque municipale, Ms. 184.

- ^ James McKinnon (2000, pp. 326-328).

- ^ James McKinnon (1998).

Studies

[edit]- Bailey, Terence. "Ambrosian chant". Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- Conomos, Dimitri E. (1980). "Communion Chants in Magna Graecia and Byzantium". Journal of the American Musicological Society. 33: 241–263. doi:10.2307/831112. JSTOR 831112.

- Conomos, Dimitri E. (1985). The Late Byzantine and Slavonic Communion Cycle: Liturgy and Music. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks.

- Popova, Deniza; Gerlach, Oliver (2014). "Vater Stilijan – ein Mönch aus Bačkovo-Kloster: Seine Persönlichkeit und seine Bedeutung für die bulgarisch-orthodoxe Gesangspraxis". Bulgarien-Jahrbuch. 2012: 129–157. doi:10.3726/b12817.

- Huglo, Michel; et al. "Gallican chant". Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- McKinnon, James. "Communion". Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- McKinnon, James (2000). The Advent project the later-seventh-century creation of the Roman Mass proper. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520221987. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- McKinnon, James W. (1998). "Compositional Planning in the Roman Mass Proper". Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 39: 241–245. doi:10.2307/902538. JSTOR 902538.

- Randal, Don M.; Nadeau, Nils. "Mozarabic chant". Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- Taft, Robert (1977). "The Evolution of the Byzantine 'Divine Liturgy'". Orientalia Christiana Periodica. 43: 8–30. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- Troelsgård, Christian. "Koinōnikon". Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 20 August 2012.