Cabaret

Cabaret (French pronunciation: [kabaʁɛ] ⓘ) is a form of theatrical entertainment featuring music, song, dance, recitation, or drama. The performance venue might be a pub, a casino, a hotel, a restaurant, or a nightclub[1] with a stage for performances. The audience, often dining or drinking, does not typically dance but usually sits at tables. Performances are usually introduced by a master of ceremonies (M.C.). The entertainment, as performed by an ensemble of actors and according to its European origins, is often (but not always) oriented towards adult audiences and of a clearly underground nature. In the United States, striptease, burlesque, drag shows, or a solo vocalist with a pianist, as well as the venues which offer this entertainment, are often advertised as cabarets.

Etymology

[edit]The term originally came from Picard language or Walloon language words camberete or cambret for a small room (12th century). The first printed use of the word kaberet is found in a document from 1275 in Tournai. The term was used since the 13th century in Middle Dutch to mean an inexpensive inn or restaurant (caberet, cabret).[2]

The word cambret, itself probably derived from an earlier form of chambrette, little room, or from the Norman French chamber meaning tavern, itself derived from the Late Latin word camera meaning an arched roof.[3]

National history

[edit]France (from 15th century)

[edit]Cabarets had appeared in Paris by at least the late 15th century. They were distinguished from taverns because they served food as well as wine, the table was covered with a cloth, and the price was charged by the plate, not the mug.[4] They were not particularly associated with entertainment even if musicians sometimes performed in both.[5] Early on, cabarets were considered better than taverns; by the end of the sixteenth century, they were the preferred place to dine out. In the 17th century, a clearer distinction emerged when taverns were limited to selling wine, and later to serving roast meats.

Cabarets were frequently used as meeting places for writers, actors, friends and artists. Writers such as La Fontaine, Moliere and Jean Racine were known to frequent a cabaret called the Mouton Blanc on rue du Vieux-Colombier, and later the Croix de Lorraine on the modern rue Bourg-Tibourg. In 1773, French poets, painters, musicians and writers began to meet in a cabaret called Le Caveau on rue de Buci, where they composed and sang songs. The Caveau continued until 1816, when it was forced to close because its clients wrote songs mocking the royal government.[4]

Entertainment venues

[edit]

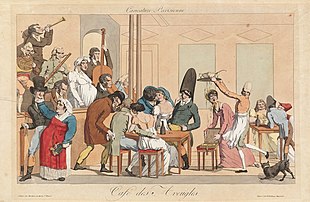

In the 18th century, the café-concert or café-chantant appeared, which offered food along with music, singers, or magicians. The most famous was the Cafe des Aveugles in the cellars of the Palais-Royal, which had a small orchestra of blind musicians. In the early 19th century, many cafés-chantants appeared around the city; the most famous were the Café des Ambassadeurs (1843) on the Champs-Élysées and the Eldorado (1858) on boulevard Strasbourg. By 1900, there were more than 150 cafés-chantants in Paris.[6]

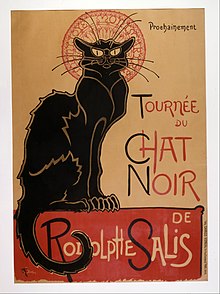

The first cabaret in the modern sense was Le Chat Noir in the bohemian neighborhood of Montmartre, created in 1881 by Rodolphe Salis, a theatrical agent and entrepreneur.[7] It combined music and other entertainment with political commentary and satire.[8] The Chat Noir brought together the wealthy and famous of Paris with the bohemians and artists of Montmartre and the Pigalle. Its clientele "was a mixture of writers and painters, of journalists and students, of employees and high-livers, as well as models, prostitutes and true grand dames searching for exotic experiences."[9] The host was Salis himself, calling himself a gentleman-cabaretier; he began each show with a monologue mocking the wealthy, ridiculing the deputies of the National Assembly, and making jokes about the events of the day. The cabaret was too small for the crowds trying to get in; at midnight on June 10, 1885, Salis and his customers moved down the street to a larger new club at 12 rue de Laval, which had a decor described as "A sort of Beirut with Chinese influences." The composer Eric Satie, after finishing his studies at the Conservatory, earned his living playing the piano at the Chat Noir.[9]

By 1896, there were 56 cabarets and cafes with music in Paris, along with a dozen music halls. The cabarets did not have a high reputation; one critic wrote in 1897 that "they sell drinks which are worth fifteen centimes along with verses which, for the most part, are worth nothing."[9] The traditional cabarets, with monologues and songs and little decor, were replaced by more specialized venues; some, like the Boite a Fursy (1899), specialized in current events, politics and satire. Some were purely theatrical, producing short scenes of plays. Some focused on the macabre or erotic. The Caberet de la fin du Monde had servers dressed as Greek and Roman gods and presented living tableaus that were between erotic and pornographic.[10]

By the end of the century, there were only a few cabarets of the old style remaining where artists and bohemians gathered. They included the Cabaret des noctambules on Rue Champollion on the Left Bank; the Lapin Agile at Montmartre; and Le Soleil d'or at the corner of the quai Saint-Michel and boulevard Saint-Michel, where poets including Guillaume Apollinaire and André Salmon met to share their work.[10]

The music hall, first invented in London, appeared in Paris in 1862. It offered more lavish musical and theatrical productions, with elaborate costumes, singing, and dancing. The theaters of Paris, fearing competition from the music halls, had a law passed by the National Assembly forbidding music hall performers to wear costumes, dance, wear wigs, or recite dialogue. The law was challenged by the owner of the music hall Eldorado in 1867, who put a former famous actress from the Comédie-Française on stage to recite verse from Corneille and Racine. The public took the side of the music halls, and the law was repealed.[11]

The Moulin Rouge was opened in 1889 by the Catalan Joseph Oller. It was greatly prominent because of the large red imitation windmill on its roof, and became the birthplace of the dance known as the French Cancan. It helped make famous the singers Mistinguett and Édith Piaf and the painter Toulouse-Lautrec, who made posters for the venue. The Olympia, also run by Oller, was the first to be called a music hall; it opened in 1893, followed by the Alhambra Music Hall in 1902, and the Printania in 1903. The Printania, open only in summer, had a large music garden which seated twelve thousand spectators, and produced dinner shows which presented twenty-three different acts, including singers, acrobats, horses, mimes, jugglers, lions, bears and elephants, with two shows a day.[11]

In the 20th century, the competition from motion pictures forced the dance halls to put on shows that were more spectacular and more complex. In 1911, the producer Jacques Charles of the Olympia Paris created the grand staircase as a setting for his shows, competing with its great rival, the Folies Bergère which had been founded in 1869. Its stars in the 1920s included the American singer and dancer Josephine Baker. The Casino de Paris, directed by Leon Volterra and then Henri Varna, presented many famous French singers, including Mistinguett, Maurice Chevalier, and Tino Rossi.[11]

Le Lido on the Champs-Élysées opened in 1946, presenting Édith Piaf, Laurel and Hardy, Shirley MacLaine, Marlene Dietrich, Maurice Chevalier, and Noël Coward. The Crazy Horse Saloon, featuring striptease, dance, and magic, opened in 1951. The Olympia Paris went through a number of years as a movie theater before being revived as a music hall and concert stage in 1954. Performers there included Piaf, Dietrich, Miles Davis, Judy Garland, and the Grateful Dead. A handful of music halls exist today in Paris, attended mostly by visitors to the city; and a number of more traditional cabarets, with music and satire, can be found.

Netherlands (from 1885)

[edit]

In the Netherlands, cabaret or kleinkunst (literally: "small art") is a popular form of entertainment, usually performed in theatres. The birth date of Dutch cabaret is usually set at August 19, 1895.[12] In Amsterdam, there is the Kleinkunstacademie (English: Cabaret Academy). It is often a mixture of (stand-up) comedy, theatre, and music and often includes social themes and political satire. In the mid twentieth century, "the big three" were Wim Sonneveld, Wim Kan, and Toon Hermans.

Nowadays, many cabaret performances by popular comedians are broadcast on national television, especially on New Year's Eve, when the oudejaarsconference is broadcast. The oudejaarsconference is a cabaret performance in which the comedian looks back on the events of the past year.

Germany (from 1901)

[edit]German Kabarett developed from 1901, with the creation of the Überbrettl (Superstage) venue, and by the Weimar era in the mid-1920s, the Kabarett performances were characterized by political satire and gallows humor.[13] It shared the characteristic atmosphere of intimacy with the French cabaret from which it was imported, but the gallows humor was a distinct German aspect.[13]

Polish (from 1905)

[edit]The Polish kabaret is a popular form of live (often televised) entertainment involving a comedy troupe, and consisting mostly of comedy sketches, monologues, stand up comedy, songs and political satire (often hidden behind double entendre to fool censors).

It traces its origins to Zielony Balonik, a famous literary cabaret founded in Kraków by local poets, writers and artists during the final years of the Partitions of Poland.[14][15]

In the interwar Poland there was a considerable number of Yiddish-language cabarets. This art form was called kleynkunst (lliterally "small art") in Yiddish.

In post-war Poland, it is almost always associated with the troupe (often on tour), not the venue; pre-war revue shows (with female dancers) were long gone.[citation needed]

United States (from 1911)

[edit]

American cabaret was imported from French cabaret by Jesse Louis Lasky in 1911.[16][17][18] In the United States, cabaret diverged into several different styles of performance mostly due to the influence of jazz music. Chicago cabaret focused intensely on the larger band ensembles and reached its peak during Roaring Twenties, under the Prohibition Era, where it was featured in the speakeasies and steakhouses.

New York cabaret never developed to feature a great deal of social commentary. When New York cabarets featured jazz, they tended to focus on famous vocalists like Nina Simone, Bette Midler, Eartha Kitt, Peggy Lee, and Hildegarde rather than instrumental musicians. Julius Monk's annual revues established the standard for New York cabaret during the late 1950s and '60s.

Cabaret in the United States began to decline in the 1960s, due to the rising popularity of rock concert shows, television variety shows,[citation needed] and general comedy theaters. However, it remained in some Las Vegas-style dinner shows, such as the Tropicana, with fewer comedy segments. The art form still survives in various musical formats, as well as in the stand-up comedy format, and in popular drag show performances.

The late 20th and early 21st century saw a revival of American cabaret, particularly in New Orleans, Chicago, Seattle, Portland, Philadelphia, Orlando, Tulsa, Asheville, North Carolina, and Kansas City, Missouri, as new generations of performers reinterpret the old forms in both music and theater. Many contemporary cabaret groups in the United States and elsewhere feature a combination of original music, burlesque and political satire. In New York City, since 1985, successful, enduring or innovative cabaret acts have been honored by the annual Bistro Awards.[19]

United Kingdom (from 1912)

[edit]The Cabaret Theatre Club, later known as The Cave of the Golden Calf, was opened by Frida Strindberg (modelled on the Kaberett Fledermaus in Strindberg's native Vienna) in a basement at 9 Heddon Street, London, in 1912. She intended her club to be an avant-garde meeting place for bohemian writers and artists, with decorations by Jacob Epstein, Eric Gill, and Wyndham Lewis, but it rapidly came to be seen as an amusing place for high society and went bankrupt in 1914. The Cave was nevertheless an influential venture, which introduced the concept of cabaret to London. It provided a model for the generation of nightclubs that came after it.[20]

"The clubs that started the present vogue for dance clubs were the Cabaret Club in Heddon Street . . . . The Cabaret Club was the first club where members were expected to appear in evening clothes. . . . The Cabaret Club began a system of vouchers which friends of members could use to obtain admission to the club. . . . the question of the legality of these vouchers led to a famous visitation of the police. That was the night a certain Duke was got out by way of the kitchen lift . . . The visitation was a well-mannered affair'[21]

Iran (until 1979)

[edit]One of the main gathering centers of cabarets in Tehran (Iranian capital) was Laleh-Zar Street. Famous Persian cabarets were active in the city until 1979. They also introduced many domestic artists. In common language, cabaret sometimes called by Iranians "home of dance" (In Persian: رقاصخانه) or "dancing place".[22]

Sweden (from 1970s)

[edit]

In Stockholm, an underground show called Fattighuskabarén (Poor House Cabaret) opened in 1974 and ran for 10 years.[23] Performers of later celebrity and fame (in Sweden) such as Ted Åström, Örjan Ramberg, and Agneta Lindén began their careers there. Wild Side Story also had several runs in Stockholm, at Alexandra's (1976 with Ulla Jones and Christer Lindarw),[24][25][26] Camarillo (1997),[27][28] Rosenlundsteatern/Teater Tre (2000),[29] Wild Side Lounge at Bäckahästen (2003 with Helena Mattsson)[30] and Mango Bar (2004).[31] Alexandra's had also hosted AlexCab in 1975,[32] as had Compagniet in Gothenburg.[33]

Serbia (from 2010s)

[edit]In 2019 the first Serbian cabaret club Lafayette opened.[34] Although Serbia and Belgrade had a rich nightlife and theater life there was no cabaret house until 2019.[35][36]

Notable venues

[edit]- Cabane Choucoune in Port-au-Prince, Haiti

- Cabaret Red Light in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich

- Café Carlyle in New York City

- Café de Paris in London, England

- The Cabaret in Indianapolis, Indiana

- Cabaret rooms at various Chuck E. Cheese's Pizza Time Theatres

- Crazy Horse in Paris, France

- Darling Cabaret in Prague

- El Mocambo in Toronto, Ontario, Canada

- El Molino in Barcelona, Spain

- Feinstein's/54 Below in New York City

- Folies Bergere in Paris, France

- Lafayette in Belgrade, Serbia

- Lapin Agile in Paris, France

- Le Lido in Paris, France

- Le Rat Mort in Paris, France

- Metro Chicago in Chicago, Illinois

- Moulin Rouge in Paris, France

- The Tropicana in Havana, Cuba

Notable artists

[edit]- May Alix

- Josephine Baker

- Bernie Dieter

- Marlene Dietrich

- Fascinating Aïda

- Ute Lemper

- Meow Meow

- Mabel Mercer

- Eartha Kitt

- Édith Piaf

- Tino Rossi

- Lady Rizo

See also

[edit]- Cabaret (musical)

- Cabaret Paradis

- Dark cabaret

- Dinner theater

- La Soirée

- Nightclub act

- Revue

- Vedette (cabaret)

References

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Fierro, Alfred (1996). Histoire et dictionnaire de Paris. Robert Laffont. ISBN 2-221--07862-4.

Notes and citations

[edit]- ^ Latham, Alison (2002). The Oxford Companion to Music. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 189. ISBN 9780198662129.

- ^ "Etymology of Cabaret" (in French). Ortolong: site of the Centre National des Resources Textuelles et Lexicales. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ "Cabaret definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 2018-08-15.

- ^ a b Fierro, Alfred (1996). Histoire et Dictionnaire de Paris. Robert Laffont. ISBN 2-221-07862-4., page 737

- ^ Jim Chevallier, A History of the Food of Paris: From Roast Mammoth to Steak Frites, 2018, ISBN 1442272821, pp. 67-80

- ^ Fierro (1996), page 744

- ^ Meakin, Anna (2011-12-19). "Le Chat Noir: Historic Montmartre Cabaret". Bonjour Paris. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

- ^ (Haine 8).Haine, W.Scott (2013). The Thinking Space: The Café as a Cultural Institution in Paris, Italy and Vienna. Ashgate. p. 8. ISBN 9781409438793. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2013-11-17.

- ^ a b c Cited in Fierro, Histoire et Dictionnaire de Paris, pg. 738

- ^ a b Fierro (1996) page 738

- ^ a b c Fierro (1996), page 1006

- ^ Willem Frijhoff, Marijke Spies (2004) Dutch Culture in a European Perspective: 1900, the age of bourgeois culture Archived 2016-05-22 at the Wayback Machine, p.507

- ^ a b (1997) The new encyclopaedia Britannica Archived 2016-04-28 at the Wayback Machine, Volume 2, p.702 quote:

It retained the intimate atmosphere, entertainment platform, and improvisational character of the French cabaret but developed its own characteristic gallows humour. By the late 1920s the German cabaret gradually had come to feature mildly risque musical entertainment for the middle-class man, as well as biting political and social satire. It was also a centre for underground political and literary movements. [...] They were the centres of leftist of opposition to the rise of the German Nazi Party and often experienced Nazi retaliation for their criticism of the government.

- ^ The Little Green Balloon (Zielony Balonik). Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine Akademia Pełni Życia, Kraków. (in English and Polish)

- ^ Zielony Balonik. Archived 2012-04-01 at the Wayback Machine 2011 Instytut Książki, Poland.

- ^ Vogel, Shane (2009) The scene of Harlem cabaret: race, sexuality, performance Archived 2016-04-28 at the Wayback Machine, ch.1, p.39

- ^ Erenberg, Lewis A. (1984) Steppin' out: New York nightlife and the transformation of American culture, 1890-1930 Archived 2016-05-11 at the Wayback Machine pp.75-76

- ^ Malnig, Julie (1992) Dancing till dawn: a century of exhibition ballroom dance Archived 2016-05-20 at the Wayback Machine, p.95

- ^ Hall, Kevin Scott. "@ the 2010 Bistro Awards" Archived 2011-07-10 at the Wayback Machine. Edge magazine, April 15, 2010

- ^ "The programme and menu from the Cave of the Golden Calf, Cabaret and Theatre Club - Explore 20th Century London". 20thcenturylondon.org.uk. Archived from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ 'A Round of the Night Clubs' G H Fosdyke Nichols p 945 in Wonderful London ed. St. John Adcock 1927

- ^ Entekhab.ir, پایگاه خبری تحلیلی انتخاب | (2023-05-29). "گزارشی از شب های تهران ۴۷ سال پیش / آمارهای قابل توجه درمورد تهرانی ها و خرج هایی که صرف خوشگذرانی می کردند". fa (in Persian). Retrieved 2023-05-29.

- ^ "About Swenglistic Underground - Facebook". Facebook.com. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ Kalle Westerling (2006) La Dolce Vita ISBN 91-85505-15-3 pp. 20-22

- ^ Christer Lindarw and Christina Kellberg in This Is My Life ISBN 978-91-7424-533-2 pp. 75-76

- ^ Sten Hedman (January 14, 1976) Damernas Värld Stockholm "Wild side story stans bästa show" p. 10[circular reference]

- ^ Eva Norlén (July 21, 1997) Aftonbladet "Åtta handplockade artister lovar en helvild kväll" p. 37

- ^ Kathy Riley (July 16, 1997) Stockholm International SR International – Radio Sweden

- ^ Linda Romanus, Tidningen Södermalm / Nöjesrepubliken, 24. Juni 2000, "KABARÉ: Wild side story till Gamla stan" p. 22

- ^ What's On by the City of Stockholm (July 2003) "Wild Side Story – What Leonard Bernstein Didn't Write" p. 16

- ^ What's On by the City of Stockholm (July 2004) "Don't Miss Wild Side Story in English" p. 12

- ^ Lisbeth Borger-Bendegard in Svenska Dagbladet 1975-09-14 "Man borde inte sova ..." p. 20 & 1975-10-24 "Krogen just nu; vilket hålligång!" p. 17

- ^ Lasse Råde in Göteborgs-Tidningen 1975-11-21 "Jubelshow!" p. 16

- ^ "Pariski duh u Beogradu - otvoren "Lafayette" cuisine cabaret club".

- ^ "Opening of a new nightclub in Belgrade - Lafayette.Otvaranje novog nocnog kluba u Beogradu - Lafayette. – ATAIMAGES.RS".

- ^ "Laffayete Belgrade". lafayette.rs. Retrieved 2022-11-22.

External links

[edit]- An Anatomy of Dutch Cabaret article from the magazine The Low Countries (1994)

- Dutch cabaret in 8 steps article on 'The Netherlands by numbers' (2015)

- The Cabaret, 1921 painting by Alexander Deyneka