Kingsnorth power station

| Kingsnorth power station | |

|---|---|

Kingsnorth Power Station Viewed from the west in October 2007 | |

| |

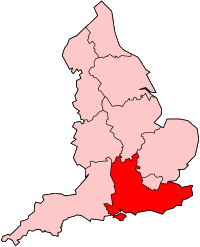

| Country | England |

| Location | Hoo St Werburgh Kent |

| Coordinates | 51°25′08″N 0°36′10″E / 51.418947°N 0.602702°E |

| Status | Decommissioned and demolished |

| Construction began | 1963[1] |

| Commission date | 1970[2] |

| Decommission date | December 2012[3] |

| Owners | CEGB, PowerGen, E.ON UK |

| Operators | Central Electricity Generating Board (1970–1990) PowerGen (1990–2002) E.ON UK (2002–2012) |

| Thermal power station | |

| Primary fuel | Coal |

| Secondary fuel | Oil-fired |

| Tertiary fuel | Biofuel |

| Site area | 162 hectare |

| Chimneys | One (198 m, 650 ft) |

| Cooling towers | None |

| Cooling source | River / sea water |

| Power generation | |

| Units operational | 4 × 500 MW |

| Make and model | GEC – Parsons |

| Units decommissioned | All |

| Annual net output | see text |

| External links | |

| Commons | Related media on Commons |

grid reference TQ809721 | |

Kingsnorth power station was a dual-fired coal and oil power station on the Hoo Peninsula at Medway in Kent, South East England. The four-unit Hinton Heavies station was operated by energy firm E.ON UK, and had a generating capacity of 2,000 megawatts.[4] It was capable of operating on either coal or oil, though in practice oil was used only as a secondary fuel or for startup.[5] It was also capable of co-firing biofuel, up to a maximum of 10% of the station's fuel mix.[4]

A replacement power station, also coal-fired, was considered by owners E.ON, but plans were abandoned. The proposed replacement attracted substantial public protests and criticism, including the 2008 Camp for Climate Action.

History

[edit]Built on the site of the former World War I Royal Naval airship base RNAS Kingsnorth,[6] Kingsnorth power station began construction in 1963.[1] It began power generation in 1970 when commissioned by the Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB).[7][8] Construction of the station was completed in 1973.[1] From 1975 to the early 1980s, Kingsnorth was linked to the London power grid by HVDC Kingsnorth, one of the few examples of high-voltage direct current transmission then in use.

On the evening of 2 January 2010, a fire broke out in one of the pump rooms of the power station. The fire was put out by 15 fire engines and five specialist units, though the building was badly damaged and had to be shut down.[9]

Proposed replacement

[edit]As a replacement for the four old Kingsnorth units, in October 2006 E.ON proposed the construction of two new coal-fired units, Kingsnorth Units 5 and 6. They had proposed constructing two new 800 MW supercritical coal-fired power units on the site, to be operational "as early as 2012".[10] E.ON expected the supercritical units to reduce carbon dioxide emissions per unit of electricity by around 20%, as compared to the former subcritical plant.[11] E.ON also said the new units would be "capture ready" to allow the option of retrofitting with carbon capture and storage (CCS). Their environmental statement read:

CCS will be considered as an option...subject to the process of CCS being allowed by law and incentivised by a suitable framework and technological hurdles for the process being overcome.[11]

On 31 March 2008 E.ON announced that the proposed station would be used in a bid for the Government's CCS competition.[12][13] In addition E.ON proposed that the planning decision should be delayed until after the Government has completed its consultation on CCS.

The proposed station came under considerable criticism from groups including Christian Aid (who noted that the emissions from the plant would be over 10 times the annual emissions from Rwanda),[14] Greenpeace,[15] The Royal Society,[16] the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds,[17] the World Development Movement,[18] the World Wide Fund for Nature[19] and CPRE.[20]

Climate scientist and head of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies James E. Hansen condemned the building of new coal power stations stating: "In the face of such threats [from climate change] it is madness to propose a new generation of power plants based on burning coal, which is the dirtiest and most polluting of all the fossil fuels. We need a moratorium on the construction of coal-fired power plants and we must phase out the existing ones within two decades".[21] He is however more accepting of coal with CCS stating that, "Coal could still be a long-term energy source for power plants, if the carbon dioxide is captured and sequestered underground".[22] Greenpeace is sceptical that CCS technology is viable.[23]

On 30 June 2008, it was announced that the Kingsnorth project had proceeded to the next stage of the competition (prequalification) with three other competitors.[24] But in March 2009, Ed Miliband said that he was postponing a decision on Kingsnorth, and in the following month the E.ON chief executive said that, "Without commercial carbon capture, [the proposed station was] 'game over'".[25][26] On 7 October 2009, E.ON postponed the replacement until at least 2016, before 20 October 2010 when it was announced that the proposal had been shelved.[27]

Closure and demolition

[edit]The station closed as a result of the EU's Large Combustion Plant Directive (LCPD), which required stations that were not equipped with flue-gas desulfurization (FGD) technology to close after 20,000 hours of operation from 1 January 2008 or the end of 2015, whichever came first. Kingsnorth ceased generation on 17 December 2012, having consumed all its LCPD hours.[28] Demolition of the coal handling plant commenced on 23 October 2014 with a series of controlled explosions. The station's turbine hall was demolished on 9 July 2015.[7] The final part of the boiler house was demolished by explosion on 27 July 2017.[29] The 650 ft (198m) concrete chimney was demolished by explosives at 10:00 am on 22 March 2018.[30]

Specification

[edit]Civil engineering

[edit]| Site area | 400 acres (162 hectares) |

|---|---|

| Turbine hall | 954 ft × 135 ft; height 110 ft (290.7 m × 41.2m; height 33.5 m) |

| Boiler house each | 370 ft × 165 ft; height 234 ft (112.7 m × 50.3m height 71.3 m) |

| Auxiliary Gas Turbine House | 180 ft × 90 ft; height 48 ft (55.4 m × 27.7m; height 14.8 m) |

| 400 kV substation | 700 ft × 434 ft; height 70 ft (213.3m × 132.2 m; height 21.3 m) |

| 132 kV substation | 296 ft × 82 ft; height 50 ft (90.2 m × 25 m; height 15.3 m) |

| Chimney | 4 × 23 ft dia (4 × 7 m dia) flues |

| Height | 650 ft (198 m) |

| Windshield dia. | at base: 86 ft (26.2 m) |

| Windshield dia. | at top: 64.7 ft (19.7 m) |

| Circulating water pump house | 200 ft × 126 ft; height 32 ft (60.9 m × 38.4 m; height 9.8 m) |

Main turbines

[edit]The main turbines were of the five cylinder tandem compound design with steam inlet conditions of 538°C and 2,300 p.s.i.g. with an exhaust condition of 1.1 in Hg. Each turbine had a maximum continuous rating of 500 MW with an additional overload capacity of 26.5 MW for three, one-hour periods per day at a slightly reduced efficiency. The cylinder arrangement consisted of a single flow High Pressure (HP), a double flow Intermediate Pressure (IP), and three double flow Low Pressure (LP) cylinders. The three LP cylinders exhausted through six outlets into an under slung axial flow condenser. All cylinders were of double shell construction and the rotors were stiff and solidly coupled with a thrust bearing sited between HP and IP cylinders. Four HP throttle valves and four IP interceptor valves were mounted directly onto their respective cylinders. The HP rotor consisted of a solid forged rotor with eight stages of continually shrouded vortex blading. Each flow of the double flow solid forged IP rotor had seven stages of similar blading. For development purposes some of the L.P. rotors were solid forged and others were of welded construction, each flow carried six stages of blading. Unique arch braced cover banding was used as shrouding and this negated the need for lacing wires between the blades. The final stage blades were 37 inches long on a base diameter of 60 inches. Stellite erosion shields were fitted to the inlet edges of the moving blades of the last two stages of each L.P. flow. Steam was tapped off the main turbine for use in the regenerative feed heaters and for driving the turbine driven steam feed pump. No. 7 HP heaters and the turbine driven feed pump were supplied with steam from the HP cylinder exhaust (cold reheat steam) at 592 p.s.i.g. Tapping points on the feed pump turbine supplied bleed steam to Nos. 5 and 6 HP heaters. The exhaust steam from the feed pump turbine was taken to the IP/LP cross under pipe. Bleed steam was tapped off the LP turbine before the second stage for the deaerator, before the third stage for the No. 3 direct contact heater, before the fourth stage for the No. 2 direct contact heater and before the fifth stage for the No. 1 direct contact heater.

| Type | Tandem compound design |

|---|---|

| No of cylinders | Five

|

| Speed | 3,000 r.p.m. |

| Turbine heat rate | 7,540 BThU / Kwh (7,955 J / Kwh) |

| Steam pressure at ESV. | 2,300 p.s.i.g. (159.6 bar) |

| Steam Flow at ESV. | 3,500,000 lbs / hr. |

| Steam temperature at ESV | 538 °C |

| Steam pressure at IV | 590 p.s.i.g (40.0 bar) |

| Steam Flow at IV | 2,900,000 lbs / hr. |

| Steam temperature at IV | 538 °C |

Feed heating system and feed pumps

[edit]Seven main stages of regenerative feed heating were provided. These consisted of three separate direct contact low-pressure heaters, a deaerator, and two parallel lines each of three stages of high-pressure heaters. Each stage consisted of two head down indirect or non-contact heaters. These six H.P. heaters were arranged in two parallel banks to give a final feed temperature of 254 °C. All H.P. heater drains were cascaded through flash boxes, the No. 5A and 5B heater drains being cascaded from flash boxes to either the deaerator or the main turbine condenser. Several earlier stages of condensate and feed heating was provided by the generator coolers and the gland steam vent condenser. Circulation of condensate and feed water through the various stages of feed heating was provided by three 50 per cent duty two-stage extraction pumps, two 100 per cent duty glandless deaerator lift pumps and one 100 per cent duty main turbine driven boiler feed pump with two 50 per cent duty starting and standby electrically driven boiler feed pumps. Surge and make up capacity was provided on a station basis by two 1,500,000 gallon reserve feed water tanks.

The feed pumps took their suctions from the deaerator and discharged directly through the H.P. heaters into the boiler feed lines. The pumps were tandem units with a slow speed suction stage and a separate high-speed pressure stage coupled through an epicyclical gearbox. Each unit had an automatic microwire suction strainer supplemented by a magnetic filter section to remove any particles which may have passed the microwire 0.008 inch mesh. The main feed pump turbine oil system and gland steam system were integrated with those of the main turbine. The suction stage pump was a single stage horizontal spindle type, driven at 2,850 r.p.m. via a reduction gearbox. The pressure stage pump was a four-stage unit with floating metallic ring glands, directly coupled to the feed pump turbine and driven at 4,150 r.p.m. The main pump was designed to deliver 3,905,000 lb/hr at 2,900 p.s.i.g. The turbine was rated at 16,970 b.h.p. with inlet steam condition of 592 p.s.i.g, and 343 °C and a steam flow of 423,580 lb/hr and thus could not meet boiler feed demand until the unit was at 50 per cent of its maximum continuous rating, that was 250 megawatts.

Starting and standby pumps were of similar design to the main feed pumps but were driven by 9,000 b.h.p. motors with the suction stage directly driven by the motor at 980 r.p.m. and the pressure stage pumps through an epicyclical gearbox at 5,500 r.p.m. The drive motors were 11 kV slip-ring induction motors with a liquid resistor speed control device giving speed variation down to 70 per cent of full load speed.

| Number of L.P. heaters | Four, including a deaerator |

|---|---|

| Type | Direct contact |

| Number of HP heaters | Six ( two banks of three) |

| Final feed temperature | 254 °C |

| Main feed pumps | |

| Main feed pump flow | 3,905,000 lbs / hr (1,403,482 kg / hr) |

| Feed pressure | 2,900 p.s.i.g. (200 bar) |

| Number | One per unit steam turbine driven |

| Steam turbine | GEC Erith |

| Rating | 16,970 b.h.p. |

| Inlet steam pressure | 512 psig |

| Inlet steam temperature | 343 deg C |

| Steam flow | 423,580 lbs/hr |

| Pumps | Sulzer |

| Type | Two stage |

| Suction stage | Single stage horizontal spindle type |

| Speed | 2,850 r.p.m. |

| Pressure stage | Four stage unit |

| Speed | 4,150 r.p.m. |

| Reduction gearbox | Epicyclical |

| Gear ratio | 1.0 / 1.45 |

| Flow | 3,905.000 lb/hr (1,403482 kg / hr) |

| Discharge pressure | 2,900 psig |

| Starting and standby feed pumps | |

| Flow | 1 ,952,500 lbs / hr (430,066 kg / h r) |

| Type of drive | 11 kV variable speed motor |

| Design rating | 9,000 bhp |

| Maximum motor speed | 980 r.p.m. |

| Maximum pump speed | 5,550 r.p.m. |

Condenser

[edit]The condenser adopted was of the under slung single shell, single pass axial type. The condenser ran the whole length of the L.P. turbine with four separate single passes, two at the top and two at the bottom, circulating water passed through each in opposite directions. Each pass had its own water box and compensating bellows. The tubes were 1 inch in diameter and 60 feet long of 70/30 aluminium brass, and expanded into double tube plates at each end. Fifteen sagging plates were provided along the length of the span. 17,336 1-inch diameter tubes were installed with an additional 1,710 1.125 inch diameter tubes in the air-cooling section. Three 50 per cent duty Nash Hytor air extraction pumps were provided with an additional quick start exhauster.

| Type | Under-slung axial flow with four single passes |

|---|---|

| Condenser back pressure | 1.1 in Hg abs. |

| Number of tubes | 19,046 |

| Length of tubes | 60 ft (18.3 m) |

Main generators

[edit]Each 3,000 r.p.m. two-pole generator was rated at 500 Megawatt with a power factor of 0.85, but they also provided a continuous over-load output of 526.5 MW with increased hydrogen pressure. The rotor and stator cores were cooled by hydrogen at a normal pressure of 60 p.s.i.g. with the stator windings water-cooled. Excitation was supplied from a self-excited, pilot alternator and a main exciter-alternator with a solid-state rectifier. The voltage of the generator output was 23.5 kV, this was passed to a 600 MVA transformer which stepped up the voltage to 400 kV for direct connection, through high voltage circuit breakers, to the grid system.

| Maximum continuous rating | 500 MW at 0.85 power factor |

|---|---|

| Speed | 3,000 r.p.m. |

| No of Phases | Three |

| Output Frequency | 50 Hz. |

| Stator voltage | 23.5 kV |

| Stator cooling medium | Water and hydrogen |

| Rotor cooling medium | Hydrogen at 60 p.s.i.g. (4.1 bar) |

| No. of Poles | Two |

| Exciters | AC pilot with AC / DC solid state rectifier |

| Main exciter output | 2,940 amps 520 volts DC |

Circulating water system

[edit]Water for cooling the turbine condensers was drawn from the River Medway; it entered the station through two 11 ft 3 in square concrete pressure culverts. These were screened by double-entry rotary drum screens to retain any large particles of foreign matter. Four concrete volute cooling water pumps impelled water to the units cooling systems. All water extracted from the river was returned via two culverts of similar size to the inlets passing over a stone weir to Damhead Creek. The whole system was approximately two miles in length. The discharge culverts had vacuum-breaking valves to cushion any surges caused in the event of an emergency shutdown of the cooling water pumps. Two auxiliary pumps were provided for dewatering the inlet culvert and to give auxiliary cooling services when the main units were shut down. All ferrous-based plant in contact with seawater and the unloading jetty structures was provided with cathodic protection to combat seawater corrosion.

Main boiler by International Combustion Ltd

[edit]Each boiler house was 370 feet long, 165 feet wide and 234 feet high, and housed two water-tube boilers of the divided furnace, assisted circulation, type. Each boiler was capable of producing 3,550,000 lb of steam per hour at 2,400 p.s.i.g. and 541 deg C at the superheated outlet, with reheat of 2,900,000 lb per hour from 348 to 541 deg C and 590 psig at the reheater outlet, based on a final feed temperature at the economiser inlet of 254 degC. In order to take advantage of the price and availability of coal and oil in the 1960s, each furnace (which was of a fully welded membrane wall construction) was designed to operate on either fuel with a (maximum continuous rating) efficiency on coal of 90 per cent and 89 per cent on oil. For the original oil firing mode, heavy fuel oil with a viscosity of up to Redwood No. 1 6,000 sec was fed into the furnace by 48 burners arranged at the eight corners in vertical banks of six, the bottom bank being arranged in two groups for use in light up. The pulverised fuel burners were interspersed with the three lower banks of oil burners. Seven stages of superheater and two stages of reheater were provided and as the final steam temperatures were only 541 deg C, Austenitic stainless steels were not used. Two all-welded, continuous loop, transverse finned tube economisers were arranged end to end to operate in parallel. Two Howden regenerative air heaters were provided together with two bled steam air heaters located between the forced draught fans and the main air heaters. These bled steam air heaters were to be used for cold start-up and when firing oil.

Two 1,180 hp Forced Draught fans are installed and two 1,565 hp Induced Draught fans were installed, the latter drawing gasses from three Davidson "R" type straight flow mechanical dust collectors via three Sturtevant parallel plate electrostatic precipitators. For coal firing, five International Combustion Lopulco Pressure Mills supplied pulverised coal to the furnace, each mill feeding a horizontal ring of eight tilting burners arranged for a tangential firing configuration from each corner of the divided furnace. The arrangement, coupled with a 15-inch gap at either side of the division wall was designed to balance the combustion conditions in each furnace.

| Main boilers | Assisted circulation, single drum, Divided furnace |

|---|---|

| Maximum continuous rating | 3,550,000 lbs / hr (1,610,250 kg / hr) |

| Superheater outlet pressure | 2,400 p.s.i.g. (166 bar) |

| Superheater outlet temperature | 541 deg C |

| Reheater steam flow | 2,900,000 lbs / hr (1,315,418 kg / hr) |

| Reheater outlet pressure | 590 p.s.i.g. (40.7 bar) |

| Reheater inlet temperature | 348 deg C |

| Reheater outlet temperature | 541 deg C |

| Economiser water inlet temperature | 254 degC |

| Drum pressure | 2,590 p.s.i.g. (178 bar) |

Ash and dust handling

[edit]Ash collected at the bottom of the boilers when in the coal burn regime and was removed after quenching by water sluices. Two crushers were fitted on each boiler to reduce any large ash to a manageable slurry. Dust and grit from the precipitator that cleansed the flue gases was collected in either a wet or dry state and was either discharged to dust hoppers for resale or pumped out as slurry to lagoons on the east side of the station.

Water treatment

[edit]Water of high purity was required for use in high pressure boilers. This called for a demineralisation plant of several processes capable of handling one million gallons a day. The water was passed through a cation unit, where the salts were converted into their corresponding acids and then through a scrubber tower for carbon dioxide removal. After passage through an anion unit for acid removal and neutralisation, the water was further "polished" in one of the three mixed-bed units to render it suitable for "make-up" for the feed water systems.

Gas turbines

[edit]Four 22.4 MW English Electric gas turbine generators were provided housed in a separate sound proof building. Each powered by two distillate fuelled Rolls-Royce 1533 Avon gas turbines. The expansion turbines were directly coupled to 28 MVA air-cooled alternators. The alternators supplied the 11 kV unit boards direct and each gas turbine was provided with an 11 kV/415 V transformer to power auxiliaries. The gas turbine auxiliaries could also be supplied by a 62.5 kVA standby diesel driven alternator set. This enabled the station to be started when completely disconnected from the grid system (black start). The gas turbines, which were equipped with automatic synchronising facilities, could be selected to start up automatically if the grid system fell below 49.7 Hz.

| Number | Four |

|---|---|

| Rated output | 22.4 MW |

| Gas turbine engines | Rolls-Royce 1533 Avon |

| Type of fuel | Gas Oil |

| Generated voltage | 11 kV |

Auxiliary boilers

[edit]Two auxiliary boilers capable of producing 45,000 lb per hour of steam at 400 p.s.i.g. at 260 deg C provided soot blowing steam for the main boilers during periods of light load, feed-water deaeration, main boiler steam air heating, fuel oil heating, oil storage tank heating, and heating for the auxiliary buildings.

| Number | Two |

|---|---|

| Rating | 45,000 lbs / h r (20,430 kg / h r) |

| Working pressure | 400 p.s.i.g. (27.6 bar) |

| Final steam temperature | 260 °C |

Station electrical supplies

[edit]Electrical auxiliary supplies were provided by a three voltage system: two 11 kV station boards supplied by the 132 kV substation via two 50 MVA transformers, and four 11 kV unit boards. The latter could be supplied either from the 30 MVA unit transformers, the 22,4 MW gas turbine, or from the station board inter-connectors. The feed pumps and circulating water pump motors were supplied from the 11 kV boards. A comprehensive system of auxiliary power supply included a safe supplies system for the instrumentation and control equipment,

There were approximately 115 electrical transformers within the power station ranging in size from 1.0 MVA to 660 MVA. Kingsnorth Power station supplied the National Grid system which interconnected other power stations and load centres. The electrical power was generated at 23,500 volts and, for reasons of economy, it was transmitted in the National Grid at much higher voltages. The generators fed transformers which changed the voltage to 400,000 volts and were in turn connected to bus-bars by means of switches which controlled the power. The bus-bars were a means of collecting the output from each generator allowing it to be distributed through various transmission lines carried by pylons across the country on the Super Grid. Other transformers on site switched the voltage from 400,000 to 132,000 volts and fed a further system of bus-bars to which connections via underground cable circuits supplied power to the Medway towns. Both the 400,000 volt and 132,000 volt bus-bars and switches were in covered accommodation at Kingsnorth to prevent airborne pollution of the insulators affecting their electrical efficiency. For the 400,000 volt switchgear, this had meant enclosing an area 700 feet by 440 feet to a height of 75 feet, (an air-space of 23,100,000 cubic feet).

| 400 kV Plant | |

|---|---|

| Generator transformers | Ratio 23/400 kV |

| Rating | 600 MVA |

| Super Grid transformers | Ratio 400/132 kV |

| Rating | 240 MVA |

| Switchgear | Rupturing capacity 35,000 MVA |

| Busbar rating | 4,000 amps |

| Overhead | Rating 1,800 MVA per circuit |

| 132 kV Plant | |

| Switchgear | Rupturing capacity 3,500 MVA |

| Busbar rating | 2,000 amps |

| Underground cables | Rating 120 MVA |

| 11 kV switchgear | |

| Type of circuit breaker | Air break |

| Breaking capacity | 750 MVA |

| Current rating | 2,000 amps |

| 3.3 kV switchgear | |

| Type of circuit breaker | Air break |

| Breaking capacity | 150 MVA |

| 415 volt switchgear | |

| Type of circuit breaker | Air break |

| Breaking capacity | 31 MVA |

Fire protection equipment

[edit]| Water spray pumps | Diesel driven, centrifugal, auto start |

|---|---|

| Number | Four |

| Capacity | 2,100 gpm (132.5 L/s) |

| Discharge head | 293 ft head (89.31 m head) |

| Hydrant pumps | Two diesel driven and one electric, centrifugal |

| Capacity | 1,680 gpm (106 L/s) |

| Discharge head | 301 ft head (91.74 m head)[31] |

Electricity output

[edit]Electricity output for Kingsnorth power station over the period 1968–1987 was as follows.[32]

Kingsnorth gas-turbine annual electricity output GWh.

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Kingsnorth annual electricity output GWh.

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Protests

[edit]Greenpeace – October 2007

[edit]Six Greenpeace protesters were arrested for breaking into the power station, climbing the station's chimney, painting the word Gordon on the chimney and causing an estimated £30,000 damage. They had been planning to write "Gordon, bin it", but had stopped when served with a High Court injunction. At their subsequent trial they admitted trying to shut the station down but argued that they were legally justified because they were trying to prevent climate change from causing greater damage to property elsewhere around the world. Evidence was heard from David Cameron's environment adviser Zac Goldsmith, and an Inuit leader from Greenland, both saying that climate change was already seriously affecting life around the world. The six were acquitted after arguing that they were legally justified in their actions to prevent climate change from causing greater damage to property around the world. It was the first case where preventing property damage caused by climate change has been used as part of a "lawful excuse" defence in court.[33]

In December 2008 Greenpeace received a letter from the Crown Prosecution Service revealing that the Attorney-General was close to referring the case of the Kingsnorth Six to the Court of Appeal in an effort to remove the defence of 'lawful excuse' from activists. Also in December the New York Times listed the acquittal in its annual list of the most influential ideas that will change our lives[34]

Climate Camp – August 2008

[edit]

The 2008 Camp for Climate Action was held near the power station and 50 people were arrested trying to break into the site.[35] Some of the tactics used by police during the demonstration have been the subject of complaints, a judicial review, and mainstream media criticism.[36][37][38][39] The Home Office argued that the £5.9m cost of the policing operation was justified as 70 officers had been injured, but data released under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 showed only 12 recorded injuries, none of which were serious or were caused by protesters.[40]

Occupation – October 2008

[edit]On 29 October 2008, Greenpeace activists occupied part of the power station after accessing the site using boats including the Rainbow Warrior. There was an hour-long stand-off with security staff before they boarded the plant's jetty and demonstrated while others set up camp on a concrete island owned by E.ON. Protesters projected campaign messages on the building, and then on a bulldozer brought in by the company to block the image, until the early hours of the following morning when they were served with a high court injunction.[41]

Taken off-line for four hours – November 2008

[edit]On 28 November 2008 a lone protester entered the plant undetected and shut down unit 2, one of the station's 500 MW turbines, leaving a message reading "no new coal". The turbine was offline for four hours.[42]

Greenpeace – June 2009

[edit]On 22 June 2009, ten Greenpeace activists boarded a fully loaded coal delivery ship bound for Kingsnorth.[43][44]

Alternative development

[edit]As of 2022, a development, called MedwayOne, is planned to include storage, a data centre, lorry park, and manufacturing space.[45]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Clarke, Jonathan (2013). High merit: existing English post-war coal and oil-fired power stations – Appendix. London: Historic England. p. 39.

- ^ "Power Stations in the United Kingdom (operational at the end of May 2004)" (PDF). Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ "Kingsnorth Power Station, Kent". Brown and Mason Demolition. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ a b "E.ON UK – Kingsnorth". Archived from the original on 11 October 2007.

- ^ "Generation – Oil". E.ON UK. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007.

- ^ "RNAS Kingsnorth". Airships Online.

- ^ a b "Kingsnorth Power station turbine hall demolished". BBC News. 9 July 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ "Power station to close". ITV News. 8 March 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ "Firefighters tackle blaze at Kingsnorth power station". BBC News. 3 January 2010. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ "Proposed Replacement Coal-fired Units for Kingsnorth Power Station. Environmental Statement" (PDF). E.ON UK. pp. v. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- ^ a b "Proposed Replacement Coal-fired Units for Kingsnorth Power Station. Environmental Statement" (PDF). E.ON UK. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- ^ "E.ON enters UK Government's carbon capture and storage competition. Press release". E.ON UK. 31 March 2008. Archived from the original on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 31 March 2008.

- ^ "CCS Demonstration Competition". Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform. Retrieved 31 March 2008.

- ^ "Take action of Kingsnorth". Christian Aid. 6 February 2008. Archived from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- ^ "The new coal rush". Greenpeace. 30 April 2007. Archived from the original on 12 December 2010. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- ^ "Dear Secretary of State". 1 April 2008. Archived from the original on 9 June 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- ^ "That's what you call action". RSPB. 14 March 2008. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- ^ "Government must stop new Kingsnorth coal-fired power plant". World Development Movement. 3 January 2008. Archived from the original on 21 March 2008. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- ^ "Kingsnorth power station decision bodes badly for climate". WWF. 3 January 2008. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- ^ "Rainbow Warrior". CPRE Kent. 27 October 2008. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- ^ Leake, Jonathan (10 February 2008). "Climate scientist they could not silence". The Times. London. Retrieved 4 March 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Hansen, Jim (12 March 2007). "Special interests are the one big obstacle". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 22 May 2008. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- ^ "Won't Kingsnorth use carbon capture and storage technology?". Greenpeace. 18 February 2008. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- ^ "CCS Demonstration Prequalification". Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform. 30 June 2008. Archived from the original on 24 September 2008. Retrieved 12 August 2008.

- ^ Stelzer, Irwin (24 March 2009). "Can Ed Miliband stop the lights going out?". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- ^ Milner, Mark (17 March 2007). "Without commercial carbon capture, it's 'game over', E.ON boss tells government". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- ^ Adam, David (7 October 2009). "Kingsnorth power station plans shelved by E.ON". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

- ^ "Kingsnorth coal-fired power station ends commercial generation and will close by 31st March 2013". E.ON UK. 17 December 2012. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013.

- ^ Cox, Lynn (27 July 2017). "Boilers were blown up at Kingsnorth Power Station, in Hoo". Kent Online. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ "Kingsnorth Power station chimney reduced to rubble – BBC News". BBC Online. 22 March 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ Stather, Eric. "Brief History of the Electricity Supply Industry". Kingsnorth Muse. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ CEGB Statistical Yearbook (1968–1987), CEGB, London.

- ^ Vidal, John (6 October 2008). "Kingsnorth trial: Coal protesters cleared of criminal damage to chimney". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ^ Mingle, Jonathan (14 December 2008). "8th annual year in ideas – Climate-Change Defense". New York Times. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ Miller, Vikki; Leach, Ben (9 August 2008). "Kent power station protest: Over 50 environmental activists arrested". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ Lewis, Paul (21 July 2009). "Video shows surveillance protesters bundled to ground by police". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ Monbiot, George (22 June 2009). "Police are turning activism into a crime". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ Jamieson, Alastair (22 June 2009). "Protesters arrested for 'challenging police officers without badge numbers' lodge formal complaint". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 25 June 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ "Women's protest arrest complaint". BBC News. 22 June 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ Vidal, John (15 December 2008). "Those Kingsnorth police injuries in full: six insect bites and a toothache". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ "The vigil ends". Greenpeace. 30 October 2008.

- ^ Vidal, John (11 December 2008). "No new coal – the calling card of the 'green Banksy' who breached fortress Kingsnorth". The Guardian.

- ^ "Swimming towards a coal ship – Greenpeace campaigners block coal delivery to Kingsnorth". Greenpeace. 22 June 2009. Archived from the original on 24 June 2009.

- ^ Siddique, Haroon (22 June 2009). "Greenpeace activists board coal ship bound for Kingsnorth power station". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- ^ Nelson, Katie May (18 November 2022). "Uniper to build MedwayOne on Kingsnorth power station site on Hoo Peninsula creating 2,000 jobs". Kent Online. Archived from the original on 24 November 2022. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

External links

[edit]- Kingsnorth Muse – History and pictures – History of the station with pictures and features covering 40 or so years.

- Kingsnorth power station – General information on Kingsnorth Power Station, including references to the Nature Reserve, one of the few of its kind in the region.

- No new coal – A lobby group opposing the replacement planned by E.ON

- Coal-fired power stations in England

- E.ON

- Power stations in South East England

- Environmental protests in the United Kingdom

- Former coal-fired power stations in the United Kingdom

- Demolished power stations in the United Kingdom

- Former power stations in England

- 1970 establishments in England

- 2012 disestablishments in England

- Energy infrastructure completed in 1973

- Buildings and structures demolished in 2018

- Medway