Kim Stanley Robinson

Kim Stanley Robinson | |

|---|---|

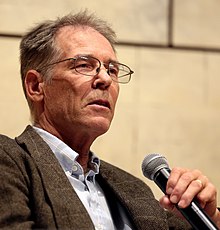

Robinson in 2017 | |

| Born | March 23, 1952 Waukegan, Illinois, U.S. |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Education | University of California, San Diego (BA, PhD) Boston University (MA) |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Academic background | |

| Thesis | The Novels of Philip K. Dick (1982) |

| Doctoral advisor | Donald Wesling |

| Other advisors | Frederic Jameson |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | English and American literature |

| Sub-discipline | Science fiction |

| Institutions | |

| Notable works | Mars trilogy |

Kim Stanley Robinson (born March 23, 1952) is an American science fiction writer best known for his Mars trilogy. Many of his novels and stories have ecological, cultural, and political themes and feature scientists as heroes. Robinson has won numerous awards, including the Hugo Award for Best Novel, the Nebula Award for Best Novel and the World Fantasy Award. The Atlantic has called Robinson's work "the gold standard of realistic, and highly literary, science-fiction writing."[1] According to an article in The New Yorker, Robinson is "generally acknowledged as one of the greatest living science-fiction writers."[2]

Early life and education

[edit]Robinson was born in Waukegan, Illinois. He moved to Southern California as a child.[3]

In 1974, he earned a B.A. in literature from the University of California, San Diego.[4] In 1975, he earned an M.A. in English from Boston University. In 1978 Robinson moved to Davis, California, to take a break from his graduate studies at the University of California, San Diego (UC San Diego). During this time, he worked as a bookseller for Orpheus Books. He also taught freshman composition and other courses at University of California, Davis.[5]

In 1982, Robinson earned a PhD in English from UC San Diego.[4] His original PhD advisor was literary critic and Marxist scholar Fredric Jameson,[6] who had pointed Robinson toward works by Philip K. Dick. Jameson described Dick to his student as "the greatest living American writer".[4] Jameson moved to UC Santa Cruz and Robinson finished his doctoral thesis under Donald Wesling.[7] The dissertation was entitled The Novels of Philip K. Dick.[8]

Career

[edit]In 2009, Robinson was an instructor at the Clarion Workshop.[9] In 2010, he was the guest of honor at the 68th World Science Fiction Convention, held in Melbourne.[10] In April 2011, Robinson presented at the second annual Rethinking Capitalism conference, held at the University of California, Santa Cruz.[11] Among other points made, his talk addressed the cyclical nature of capitalism.[12]

Robinson was appointed as a Muir Environmental Fellow in 2011 by John Muir College at UC San Diego.[13]

Major themes

[edit]Nature and culture

[edit]Sheldon Brown described Robinson's novels as ways to explore how nature and culture continuously reformulate one another; Three Californias Trilogy as California in the future; Washington DC undergoing the impact of climate change in the Science in the Capital series; or Mars as a stand-in for Earth in the Mars trilogy to think about re-engineering on a global scale, both social and natural conditions.[14]

Ecological sustainability

[edit]Virtually all of Robinson's novels have an ecological component; sustainability is one of his primary themes (a strong contender for the primary theme would be the nature of a plausible utopia). The Orange County trilogy is about the way in which the technological intersects with the natural, highlighting the importance of keeping the two in balance. In the Mars trilogy, one of the principal divisions among the population of Mars is based on dissenting views on terraforming. Colonists debate whether or not the barren Martian landscape has a similar ecological or spiritual value when compared with a living ecosphere like Earth's. Forty Signs of Rain has an entirely ecological thrust, taking global warming as its principal subject.

Economic and social justice

[edit]

Robinson's work often explores alternatives to modern capitalism.[15] In the Mars trilogy, it is argued that capitalism is an outgrowth of feudalism, which could be replaced in the future by a more democratic economic system. Worker ownership and cooperatives figure prominently in Green Mars and Blue Mars as replacements for traditional corporations. The Orange County trilogy explores similar arrangements; Pacific Edge includes the idea of attacking the legal framework behind corporate domination to promote social egalitarianism. Tim Kreider writes in the New Yorker that Robinson may be our greatest political novelist and describes how Robinson uses the Mars trilogy as a template for a credible utopia.[2] His works have made reference to real-world examples of economic organization that have been cited as examples of alternatives to conventional capitalist structures, such as the Mondragon Corporation and the Kerala model.[16]

Robinson's writing also reflects an interest in economic models that reject the growth-oriented basis of capitalism: Robert Markley has identified the work of Murray Bookchin as an influence on his thinking, as well as steady-state economics.[16]

Robinson's work often portrays characters struggling to preserve and enhance the world around them in an environment characterized by individualism and entrepreneurialism, often facing the political and economic authoritarianism of corporate power acting in this environment. Robinson has been described as anti-capitalist, and his work often portrays a form of frontier capitalism that promotes egalitarian ideals that closely resemble socialist systems, but faced with a capitalism that is maintained by entrenched hegemonic corporations. In particular, his Martian Constitution draws upon social democratic ideals explicitly emphasizing a community-participation element in political and economic life.[17]

Robinson's works often portray the worlds of tomorrow in a manner similar to the mythologized American Western frontier, showing a sentimental affection for the freedom and wildness of the frontier. This aesthetic includes a preoccupation with competing models of political and economic organization.

The environmental, economic, and social themes in Robinson's oeuvre stand in marked contrast to the right-libertarian science fiction prevalent in much of the genre (Robert A. Heinlein, Poul Anderson, Larry Niven, and Jerry Pournelle being prominent examples). He has been described as "one of America's best-selling […] left-wing novelists" and his work has been called "probably the most successful attempt to reach a mass audience with an anti-capitalist utopian vision since Ursula K. Le Guin's 1974 novel, The Dispossessed".[18]

Scientists as heroes

[edit]Robinson's work often features scientists as heroes. They are portrayed in a mundane way compared to most work featuring scientists: rather than being adventurers or action heroes, Robinson's scientists become critically important because of research discoveries, networking and collaboration with other scientists, political lobbying, or becoming public figures. Robinson captures the joy of scientists as they work at something they care about.[19] Robert Markley has argued that Robinson "views science as the model for a utopian politics... Even in Robinson's novels that don't seem to be sci-fi, like Shaman, the inductive method, the collective search for greater knowledge about the world that can be put to use for the good for all, is front and center".[16] The Mars trilogy and The Years of Rice and Salt rely heavily on the idea that scientists must take responsibility for ensuring public understanding and responsible use of their discoveries. Robinson's scientists often emerge as the best people to direct public policy on important environmental and technological questions, of which politicians are often ignorant.

Climate change and global warming

[edit]Related to Robinson's focus on the environment are his themes of the imminent catastrophe of global warming and the need to limit greenhouse gas emissions in the present day. His 2012 novel 2312 explores the detrimental, long-term effects of climate change, which include food shortages, global instability, mass extinction, and 7-metre (23 ft) sea level rise that has drowned many major coastal cities.[1] The novel condemns the people of the period it calls "the Dithering", from 2005 to 2060, for failing to address climate change and thereby causing mass suffering and death in the future.[1] Robinson and his work accuse global capitalism for the failure to address climate change.[1] In his 2017 novel New York 2140 Robinson explores the themes of climate change and global warming, setting the novel in the year 2140 when the New York City he imagines is beset by a 50-foot (15 m) sea level rise that submerges half of the city.[20] Climate change is also the focus of his Science in the Capital series[1] and his 2020 novel The Ministry for the Future.

Awards and honors

[edit]Asteroid 72432 Kimrobinson, discovered by astronomer Donald P. Pray in 2001, was named in his honor.[21] The official naming citation was published by the Minor Planet Center on April 22, 2016 (M.P.C. 99892).[22]

In 2008, Time magazine named Robinson a "Hero of the Environment" for his optimistic focus on the future.[19]

Personal life

[edit]Robinson and his wife have two sons. Robinson has lived in Washington, D.C., California, and during some of the 1980s, in Switzerland. At times, Robinson was a stay-at-home dad.[6] He later moved to Davis, California, in a cohousing community.[6]

Robinson has described himself as an avid backpacker, with the Sierra Nevada mountains serving as his home range and a big influence on how he sees the world.[5]

Politically, Robinson identifies as a democratic socialist, and in a February 2019 interview mentioned he is a dues-paying member of the Democratic Socialists of America.[26] He has also remarked that libertarianism has never "[made] any sense to me, nor sounds attractive as a principle."[27]

Works

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Beauchamp, Scott (April 1, 2013). "In 300 Years, Kim Stanley Robinson's Science Fiction May Not Be Fiction". The Atlantic. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- ^ a b Kreider, Tim (December 13, 2013). "Our Greatest Political Novelist?". The New Yorker. Retrieved September 6, 2015.

- ^ Adams, John Joseph (June 6, 2012). "Sci-Fi Scribes on Ray Bradbury: 'Storyteller, Showman and Alchemist'". Wired. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c Potts, Stephen (July 11, 2000). "UCSD Guestbook: Kim Stanley Robinson". UCTV. University of California Television. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

- ^ a b Hudsen, Jeff (October 18, 2004). "Davis a perfect fit for a sci-fi novelist". The Davis Enterprise. Archived from the original on November 22, 2004. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- ^ a b c Bioneers (November 12, 2015), Kim Stanley Robinson – Rethinking Our Relationship to the Biosphere | Bioneers, retrieved August 27, 2016

- ^ Heer, Jeet (October 3, 2024). "Fredric Jameson Named the System We Are Still Fighting". ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved October 5, 2024.

- ^ Robinson, Kim Stanley (1982). The novels of Philip K. Dick (PhD thesis). University of California, San Diego. ProQuest 303068187.

- ^ Doctorow, Cory (December 8, 2008). "Clarion science fiction/fantasy workshop instructors announced". Boingboing. Boinboing. Retrieved September 6, 2015.

- ^ Howell, John (May 18, 2009). "68th World Science Fiction Convention Australia 2010: Kim Stanley Robinson Guest". SFW. Archived from the original on October 9, 2015. Retrieved September 6, 2015.

- ^ Pittman, Jennifer (April 2, 2011). "Rethinking Capitalism conference at UCSC to examine the cost of sustaining a fragile system". Santa Cruz Sentinel News. Retrieved September 6, 2015.

- ^ "Bruce Initiative on Rethinking Capitalism | 2011 Conference". Archived from the original on August 26, 2011. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

- ^ Iannuzzi, Giulia. "Science, Engagement, Estrangement:Remarks on Kim Stanley Robinson's Californian Ecotopia" (PDF). EUT. EUT – Edizioni Università di Trieste.

- ^ Brown, Sheldon (July 1, 2013). "The Literary Imagination with Jonathan Lethem and Kim Stanley Robinson". UCTV. 5:00: University of California Television. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ O'Keefe, Derrick (October 22, 2020). "Imagining the End of Capitalism With Kim Stanley Robinson". Jacobin. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ a b c Dilawar, Arvind (November 14, 2020). "Kim Stanley Robinson Is One of Our Greatest Ever Socialist Novelists". Jacobin. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ^ Some Worknotes and Commentary on the Constitution by Charlotte Dorsa-Brevia, in The Martians pp. 233–239

- ^ Smith, Jeremy (2001). "Utopic Fiction and the Mars Novels of Kim Stanley Robinson". Raintaxi. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ a b Morton, Oliver (September 24, 2008). "Heroes of the Environment 2008". Time Magazine. Retrieved September 6, 2015.

- ^ Canavan, Gerry (2017). "Utopia in the Time of Trump". Los Angeles Review of Books (LARB). Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ "(72432) Kimrobinson". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ "MPC/MPO/MPS Archive". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "Science Fiction Awards Database". sfadb. Retrieved September 7, 2015.

- ^ "Robinson Wins 2016 Heinlein Award". Locus Online. January 7, 2016. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ "2017 Clarke Foundation Awards". The Arthur C. Clarke Foundation. January 16, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- ^ Jamie Peck, Sean KB, Will Menaker (February 28, 2018). "Fully Automated Luxury Gay Space Communism w/ Kim Stanley Robinson". The Antifada (Podcast). Fans.fm. Event occurs at 54:31. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

{{cite podcast}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sethness, Javier (March 17, 2018). "Toward an Ecologically Based Post-Capitalism: Interview With Novelist Kim Stanley Robinson". Truthout. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

External links

[edit]- Kim Stanley Robinson at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- KimStanleyRobinson.info – unofficial site

- Short descriptions of K.S. Robinson's novels

- All of Kim Stanley Robinson's audio interviews on the podcast The Future And You (in which he describes his expectations of the future)

- Robinson at the Internet Book List

- Guardian interview with K.S. Robinson (Wednesday September 14, 2005)

- "Comparative Planetology: an Interview with Kim Stanley Robinson" at BLDGBLOG

- Complete list of sci-fi award wins and nominations by novel

- Interview on the SciFiDimensions Podcast (original webpage down; link to archive.org version of page.)

- "Terraforming Earth", essay by KSR at Slate, December 4, 2012

- Kim Stanley Robinson at Library of Congress, with 33 library catalog records

- Worldwatch Institute State of the World – Kim Stanley Robinson, 04/16/2013 Washington, DC

- Kim Stanley Robinson discusses Marxism, scientism and bureaucrats with The Dig podcast.

- 1952 births

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American novelists

- 21st-century American male writers

- 21st-century American novelists

- American alternate history writers

- American democratic socialists

- American humanists

- American male novelists

- American science fiction writers

- Boston University College of Arts and Sciences alumni

- Environmental fiction writers

- Hugo Award–winning writers

- Members of the Democratic Socialists of America

- Nebula Award winners

- Novelists from California

- Novelists from Illinois

- Living people

- People from Davis, California

- People from Waukegan, Illinois

- American philosophers of culture

- Philosophers of history

- American philosophers of science

- American philosophers of technology

- University of California, San Diego alumni

- World Fantasy Award–winning writers

- Writers of historical fiction set in the modern age

- Writers of historical fiction set in the Middle Ages

- Writers of historical fiction set in the early modern period

- Philip K. Dick scholars