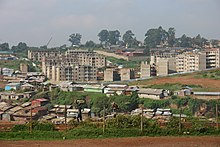

Kibera

Kibera (Nubian: Forest or Jungle[1]) is a neighbourhood of Nairobi, Kenya. It is the largest of Nairobi's slums,[2] and the second largest urban slum in Africa,[2][3][4] with an estimated population of between 600,000 and 1.2 million inhabitants.[5][6] The slum is located roughly 5 kilometers southwest of the city centre of Nairobi. Encompassing an area of 2.5 square kilometers, Kibera accounts for less than 1% of Nairobi's total area, but holds more than a quarter of its population, at an estimated density of 2000 persons per hectare.[7] The neighborhood is divided into a number of villages, including Kianda, Soweto, Gatwekera, Kisumu Ndogo, Lindi, Laini Saba, Siranga/Undugu, Makina and Mashimoni.

History

Kibera originated as a settlement in the forests outside Nairobi, when Nubian soldiers returning from service in the First World War were awarded with plots there in return for their efforts.[5] The British colonial government of the time allowed the settlement to grow informally, primarily because of the Nubians' status as former servants of the British crown, which put the colonial regime in their debt. Furthermore the Nubians, being "Detribalized Natives" had no claim on land in "Native Reserves".[citation needed] Over time, other tribes moved into the area to rent land from the Nubian landlords.

After Kenya became independent in 1963, a number of forms of housing were made illegal by the government. The new ruling affected Kibera on the basis of land tenure, rendering it an unauthorized settlement. Despite this, people continued to live there, and by the early 1970s landlords were renting out their properties in Kibera to significantly greater numbers of tenants that was permitted by law. The tenants, who are highly impoverished, cannot afford to rent legal housing, finding the rates offered in Kibera to be comparatively affordable. The number of residents in Kibera has increased accordingly despite its unauthorised nature. By 1974, members of the Kikuyu tribe predominated the population of Kibera, and had gained control over administrative positions, which is kept through political patronage. Certain land owners are protected by the local government largely due to their Kikuyu ethnicity.[8]

Presently, Kibera's residents represent all the major Kenyan ethnic background, with some areas being specifically dominated by peoples of one tribe. Many new residents come from rural areas with chronic underdevelopment and overpopulation issues. The multi-ethnic nature of Kibera's populism combined with the tribalism that pervades Kenyan politics has led to Kibera hosting a number of small ethnic conflicts throughout its century-long history. The Kenyan government owns all the land upon which Kibera stands, though it continues to not officially acknowledge the settlement; no basic services, schools, clinics, running water or lavatories are publicly provided, and what services do exist are privately owned.[5]

Slum upgrading

Kibera is one of the most studied slums in Africa, not only because it sits in the centre of the modern city, but also because UN-HABITAT, the United Nations' agency for human settlements, is headquartered close by. Ban Ki-moon visited the settlement within a month of his selection as UN secretary-general.[5]

Kibera, as one of the most pronounced slums within Kenya, is undergoing an intensive slum upgrading process. The government, UN-HABITAT and a contingent of NGOs, notably Maji na Ufanisi, are making inroads into the settlements in an attempt to facelift the housing and sanitary conditions.

There are three significant complicating factors to construction or upgrade within Kibera. The first is the rate of petty and serious crime. Building materials cannot be left unattended for long at any time because there is a very high chance of them being stolen. It is not uncommon for owners of storm-damaged dwellings to have to camp on top of the remnants of their homes until repairs can be made in order to protect the raw materials from would-be thieves.

The second is the lack of building foundations. The ground in much of Kibera is literally composed of refuse and rubbish. Dwellings are often constructed atop this unstable ground, and therefore many structures collapse whenever the slum experiences flooding, which it does regularly. This means that even well-constructed buildings are often damaged by the collapse of nearby poorly constructed ones.

The third complicating factor is the unyielding topography and cramped sprawl of the area. Few houses have vehicle access and many are at the bottom of steep inclines (which heightens the flooding risk). This means that any construction efforts are made more difficult and costly by the fact that all materials must be brought in by hand.

Clearance

On 16 September 2009 the Kenyan government, which claims ownership of the land on which Kibera stands, began a long-term movement scheme which will rehouse the people who live in slums in Nairobi.[6] The clearance of Kibera is expected to take between two and five years to complete. The entire project is planned to take nine years and will rehouse all 2 million slum residents in the city.[9] The project has the backing of the United Nations and Prime Minister Raila Odinga, who is a local MP, and is expected to cost $1.2 billion.[6][9] The new communities are planned to include schools, markets, playgrounds and other facilities.[6] The first batch of around 1500 people to leave the slum were taken away by truck on 16 September 2009 from 6.30 am local time and were rehoused in 300 newly constructed apartments with a monthly rent of around $10.[6][9]

The project start has been postponed several times as PM Odinga was unavailable to oversee the first day.[10] He was joined on the first day by Housing Minister Soita Shitanda and his assistant Margaret Wanjiru with all three assisting residents with loading their belongings onto the trucks.[10] Also present were several dozen armed police officers to oversee the arrangements and to deter any resistance.[10]

The process has been legally challenged by more than 80 people and the Kenyan High Court has stated that the government cannot begin demolition works until the case is heard in October, but will be able to demolish the homes of people who leave voluntarily before then.[6][9] The 80 plaintiffs are a mixture of middle-class landlords and Kibera residents and they claim that the land in Kibera is theirs and hence the government has no right to demolish the shacks. The Nubian community, who have lived on the land for nearly 100 years are also disappointed with the scheme and one elder has said that the present housing should be improved instead.[6]

The project has also come under fire from urban planners who say that it risks repeating the mistakes of previous schemes - poor families either shared two-roomed apartments with one or two other families in order to pay the rent, or sub-let them to middle-class families and moved back into the slums.[6] Workers earning a minimum wage in Kenya make less than US$2 per day.[11] There is also controversy over the timings of the project with the first phase, rehousing 7,500 people, being delayed by five years and one government official stating that if the project continues at the current pace it will take 1,178 years to complete.[9]

Geography and culture

Kibera is located in southwest Nairobi, roughly 5 kilometers from the city centre. Much of its southern border is bounded by the Nairobi river and the Nairobi Dam, an artificial lake that provides drinking water to the residents of the city. It is estimated that between 600,000 and 1.2 million people live in Kibera,[5] with a population density of 2000 residents per hectare.[12] Kibera is divided into a number of villages, including Kianda, Soweto, Gatwekera, Kisumu Ndogo, Lindi, Laini Saba, Siranga/Undugu, Makina and Mashimoni.

The Uganda Railway Line passes through the center of the neighbourhood, providing passengers aboard the train a firsthand view of the slum. Kibera has a railway station, but most residents use buses and matatus to reach the city centre; carjacking, irresponsible driving, and poor traffic law enforcement are chronic issues.

Kibera is heavily polluted by human refuse, garbage, soot, dust, and other wastes. The slum is contaminated with human and animal feces, thanks to the open sewage system and the frequent use of "flying toilets". The lack of sanitation combined with poor nutrition among residents accounts for many illnesses and diseases. It is estimated that one-fifth of the 2.2 million Kenyans living with HIV live in Kibera.

Kibera is home to the popular Olympic Primary School, one of the leading government schools in the country. There is a community radio station, Pamoja FM.

References in popular culture

Kibera is featured in Fernando Meirelles's film The Constant Gardener, which is based on the book of the same name by John le Carré. It is also mentioned in the music video "World on Fire" by Sarah McLachlan, which profiled the work of Carolina for Kibera, a grassroots organization named a Hero of Global Health in 2005 by Time Magazine.[13]

Robert Neuwirth devotes a chapter of his book Shadow Cities to Kibera and calls it a squatter community, predicting that places like Kibera, Sultanbeyli in Istanbul, Turkey, and Dharavi in Mumbai, India, are the prototypes of the cities of tomorrow. Among other things Neuwirth points out that such cities should be reconsidered as merely slums, as many locals were drawn to them while escaping far worse conditions in rural areas. Michael Holman's 2005 novel Last Orders at Harrods is based in a fictional version of the slum, called Kireba. Bill Bryson visited Africa for CARE and wrote a companion book called "Bill Bryson's African Diary" which includes a description of his visit to Kibera. Kibera is also the backdrop for the award-winning short film Kibera Kid which featured a cast entirely drawn from Kibera residents. The film has played in film festivals worldwide including the Berlin Film Festival and won a Student Emmy from Hollywood. In his documentary Living with Corruption Sorious Samura stayed with a family in Kibera to film the corruption that occurs even at the lowest levels of Kenyan society. Furthermore, Kibera is portrayed in the Austrian 2007 documentary Über Wasser: Menschen und gelbe Kanister.

See also

Notes

- ^ Affordable Housing Institute blog

- ^ a b A Trip Through Kenya’s Kibera Slum

- ^ Participating countries

- ^ Machetes, Ethnic Conflict and Reductionism The Dominion

- ^ a b c d e "The Strange Allure of the Slums", The Economist, 5th May 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Kenya begins huge slum clearance". BBC. 16 September 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- ^ KENYA: Kibera, The Forgotten City

- ^ The geography of Third World cities. ISBN 0-389-20671-7. (Lowder, Stella)

- ^ a b c d e "Kenya moves 1,500 slum residents to new homes". The Standard. 16 September 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- ^ a b c "Ecstasy as Kibera slum residents finally reach 'promised land' after years of waiting". The Standard. 16 September 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- ^ http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2005/61575.htm

- ^ KENYA: Kibera, The Forgotten City

- ^ Yunus Ndeti - A Brief History of Kibera, 2003

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (January 2009) |

- Clean Water for Kenyans: Multimedia story on Water Sanitation Projects in Kibera

- Commission on Legal Empowerment of the Poor: Photo story of the Toi Market in Kenya

- Hot Sun Foundation in Kibera

- Documentary about Kibera on OneWorldTV

- Carolina For Kibera

- Focus on Kibera: Shining Hope for Community (SHOFCO)

- Harvard Design Students presentation about Kibera: Kounkuey Design Initiative (KDI)*

- Greening the Ivory Tower: University design programs focus on social + environmental sustainability (Kibera featured)

- Lahash short film from the slums

- Robert Neuwirth's talk on the largest squatter communities

- CSG Kibera

- Kibera Community Youth Programme

- BBC News: Nairobi Slum Life

- Kibera slums, Macharias journey: Kibera and a story of Hope

- Video and Article on a Community Theatre for Development project in Kibera

- Photos from Kibera

- Nairobi Slums School Projects Trust

- Official website of the Map Kibera Project

- Slum Survivors Documentary film by IRIN

- [1] Article about the Kenya Slum Upgrading Program

- Sarah Junior School: A pre-primary school for 65 children operating in Kibera, operated by Kenyan locals and funded from the UK.