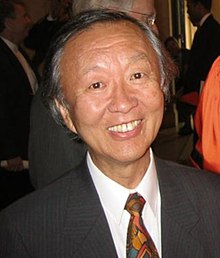

Charles K. Kao

| Charles K. Kao | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 高錕 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 高锟 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Sir Charles Kao Kuen (simplified Chinese: 高锟; traditional Chinese: 高錕; pinyin: Gāo Kūn) (November 4, 1933 – September 23, 2018) was a Chinese physicist and Nobel laureate who contributed to the development and use of fibre optics in telecommunications. In the 1960s, Kao created various methods to combine glass fibres with lasers in order to transmit digital data, which laid the groundwork for the evolution of the Internet and the eventual creation of the World Wide Web.

Kao was born in Shanghai. His family settled in Hong Kong in 1949. He graduated from St. Joseph's College in Hong Kong in 1952 and went to London to study electrical engineering. In the 1960s, Kao worked at Standard Telecommunication Laboratories, the research center of Standard Telephones and Cables (STC) in Harlow, and it was here in 1966 that he laid the groundwork for fibre optics in communication.[5] Known as the "godfather of broadband",[6] the "father of fibre optics",[7][8][9][10][11] and the "father of fibre optic communications",[12] he continued his work in Hong Kong at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and in the United States at ITT (the parent corporation for STC) and Yale University. Kao was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for "groundbreaking achievements concerning the transmission of light in fibres for optical communication".[13] In 2010, he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II for "services to fibre optic communications".[14]

Kao was a permanent resident of Hong Kong,[15] and a citizen of the United Kingdom and the United States.[3]

Early life and education

[edit]Charles Kao was born in Shanghai in 1933 and lived with his parents in the Shanghai French Concession.[16]: 1 He studied Chinese classics at home with his brother, under a tutor.[17][16]: 41 He also studied English and French at the Shanghai World School (上海世界學校)[18] that was founded by a number of progressive Chinese educators, including Cai Yuanpei.[19]

After the Communist revolution, Kao's family settled in Hong Kong in 1949. Much of his mother's siblings moved to Hong Kong in the late 1930s, among them, his mother's youngest brother took good care of him.[16]: 1 [20]

Kao's family lived in Lau Sin Street, at the edge of the North Point, a neighbourhood of Shanghai immigrants.[16] During Kao's time in Hong Kong, he studied at St. Joseph's College for 5 years and graduated in 1952.[21][22]

Kao obtained high score in the Hong Kong School Certificate Examination, which at the time was the territory's matriculation examination, qualifying him for admission to the University of Hong Kong. However, at the time electrical engineering wasn't a programme available at the University of Hong Kong, the territory's then only teritary education institute.[23][24]

Hence in 1953, Kao went to London to continue his studies in secondary school and obtained his A-Level in 1955. He was later admitted to Woolwich Polytechnic (now the University of Greenwich) and obtained his Bachelor of Electrical Engineering degree.[25][16]: 1 [26][24] He then pursued research and received his PhD in electrical engineering in 1965 from the University of London, under Professor Harold Barlow of University College London as an external student while working at Standard Telecommunication Laboratories (STL) in Harlow, England, the research center of Standard Telephones and Cables.[4][24]

Ancestry and family

[edit]Kao's father Kao Chun-Hsiang (高君湘),[16]: 13 originally from Jinshan City (now a district of Shanghai City), obtained his Juris Doctor from the University of Michigan Law School in 1925.[27] He was a judge at the Shanghai Concession and later a professor at Soochow University (then in Shanghai) Comparative Law School of China.[28][29]

His grandfather Kao Hsieh was a scholar, poet and artist,[17][30] Several writers including Kao Hsü, Yao Kuang (姚光), and Kao Tseng (高增) were also Kao's close relatives.[citation needed]

His father's cousin was astronomer Kao Ping-tse[17][31] (Kao crater is named after him[32]). Kao's younger brother Timothy Wu Kao (高鋙) is a civil engineer and Professor Emeritus at the Catholic University of America. His research is in hydrodynamics.[33]

Kao met his future wife Gwen May-Wan Kao (née Wong; 黃美芸) in London after graduation, when they worked together as engineers at Standard Telephones and Cables. She was British Chinese. They were married in 1959 in London, and had a son and a daughter, both of whom reside and work in Silicon Valley, California.[34][35] According to Kao's autobiography, Kao was a Catholic who attended Catholic Church while his wife attended the Anglican Communion.[16]: 14–15

Academic career

[edit]Fibre optics and communications

[edit]

In the 1960s at Standard Telecommunication Laboratories (STL) based in Harlow, Essex, England, Kao and his coworkers did their pioneering work in creating fibre optics as a telecommunications medium, by demonstrating that the high-loss of existing fibre optics arose from impurities in the glass, rather than from an underlying problem with the technology itself.[37]

In 1963, when Kao first joined the optical communications research team he made notes summarising the background[38] situation and available technology at the time, and identifying the key individuals[38] involved. Initially Kao worked in the team of Antoni E. Karbowiak (Toni Karbowiak), who was working under Alec Reeves to study optical waveguides for communications. Kao's task was to investigate fibre attenuation, for which he collected samples from different fibre manufacturers and also investigated the properties of bulk glasses carefully. Kao's study primarily convinced him that the impurities in material caused the high light losses of those fibres.[39] Later that year, Kao was appointed head of the electro-optics research group at STL.[40] He took over the optical communication program of STL in December 1964, because his supervisor, Karbowiak, left to take the chair in Communications in the School of Electrical Engineering at the University of New South Wales (UNSW), Sydney, Australia.[41]

Although Kao succeeded Karbowiak as manager of optical communications research, he immediately decided to abandon Karbowiak's plan (thin-film waveguide) and overall change research direction with his colleague George Hockham.[39][41] They not only considered optical physics but also the material properties. The results were first presented by Kao to the IEE in January 1966 in London, and further published in July with George Hockham (1964–1965 worked with Kao).[42][a] This study proposed the use of glass fibres for optical communication. The concepts described, especially the electromagnetic theory and performance parameters, are the basis of today's optical fibre communications.[43][44]

"What Kao did in Harlow transformed the world and provided a backbone for the internet. He was the father of fiber optics."

In 1965,[40][46][b] Kao with Hockham concluded that the fundamental limitation for glass light attenuation is below 20 dB/km (decibels per kilometer, is a measure of the attenuation of a signal over a distance), which is a key threshold value for optical communications.[47] However, at the time of this determination, optical fibres commonly exhibited light loss as high as 1,000 dB/km and even more. This conclusion opened the intense race to find low-loss materials and suitable fibres for reaching such criteria.[citation needed]

Kao, together with his new team (members including T. W. Davies, M. W. Jones and C. R. Wright), pursued this goal by testing various materials. They precisely measured the attenuation of light with different wavelengths in glasses and other materials. During this period, Kao pointed out that the high purity of fused silica (SiO2) made it an ideal candidate for optical communication. Kao also stated that the impurity of glass material is the main cause for the dramatic decay of light transmission inside glass fibre, rather than fundamental physical effects such as scattering as many physicists thought at that time, and such impurity could be removed. This led to a worldwide study and production of high-purity glass fibres.[48] When Kao first proposed that such glass fibre could be used for long-distance information transfer and could replace copper wires which were used for telecommunication during that era, his ideas were widely disbelieved; later people realized that Kao's ideas revolutionized the whole communication technology and industry.[49]

He also played a leading role in the early stage of engineering and commercial realization of optical communication.[50] In spring 1966, Kao traveled to the U.S. but failed to interest Bell Labs, which was a competitor of STL in communication technology at that time.[51] He subsequently traveled to Japan and gained support.[51] Kao visited many glass and polymer factories, discussed with various people including engineers, scientists, businessmen about the techniques and improvement of glass fibre manufacture. In 1969, Kao with M. W. Jones measured the intrinsic loss of bulk-fused silica at 4 dB/km, which is the first evidence of ultra-transparent glass. Bell Labs started considering fibre optics seriously.[51] As of 2017, fibre optic losses (from both bulk and intrinsic sources) are as low as 0.1419 dB/km at the 1.56 μm wavelength.[52]

Kao developed important techniques and configurations for glass fibre waveguides, and contributed to the development of different fibre types and system devices which met both civil and military[c] application requirements, and peripheral supporting systems for optical fibre communication.[50] In mid-1970s, he did seminal work on glass fibre fatigue strength.[50] When named the first ITT Executive Scientist, Kao launched the "Terabit Technology" program in addressing the high frequency limits of signal processing, so Kao is also known as the "father of the terabit technology concept".[50][53] Kao has published more than 100 papers and was granted over 30 patents,[50] including the water-resistant high-strength fibres (with M. S. Maklad).[54]

At an early stage of developing optic fibres, Kao already strongly preferred single-mode for long-distance optical communication, instead of using multi-mode systems. His vision later was followed and now is applied almost exclusively.[48][55] Kao was also a visionary of modern submarine communications cables and largely promoted this idea. He predicted in 1983 that world's seas would be littered with fibre optics, five years ahead of the time that such a trans-oceanic fibre-optic cable first became serviceable.[56]

Ali Javan's introduction of a steady helium–neon laser and Kao's discovery of fibre light-loss properties now are recognized as the two essential milestones for the development of fibre-optic communications.[41]

Later work

[edit]Kao joined the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) in 1970 to found the Department of Electronics, which later became the Department of Electronic Engineering. During this period, Kao was the reader and then the chair Professor of Electronics at CUHK; he built up both undergraduate and graduate study programs of electronics and oversaw the graduation of his first students. Under his leadership, the School of Education and other new research institutes were established. He returned to ITT Corporation in 1974 (the parent corporation of STC at that time) in the United States and worked in Roanoke, Virginia, first as Chief Scientist and later as Director of Engineering. In 1982, he became the first ITT Executive Scientist and was stationed mainly at the Advanced Technology Center in Connecticut.[10] While there, he served as an adjunct professor and Fellow of Trumbull College at Yale University. In 1985, Kao spent one year in West Germany, at the SEL Research Center. In 1986, Kao was the Corporate Director of Research at ITT.

He was one of the earliest to study the environmental effects of land reclamation in Hong Kong, and presented one of his first related studies at the conference of the Association of Commonwealth Universities (ACU) in Edinburgh in 1972.[57]

Kao was the vice-chancellor of the Chinese University of Hong Kong from 1987 to 1996.[58] From 1991, Kao was an Independent Non-Executive Director and a member of the Audit Committee of the Varitronix International Limited in Hong Kong.[59][60] From 1993 to 1994, he was the President of the Association of Southeast Asian Institutions of Higher Learning (ASAIHL).[61] In 1996, Kao donated to Yale University, and the Charles Kao Fund Research Grants was established to support Yale's studies, research and creative projects in Asia.[62] The fund currently is managed by Yale University Councils on East Asian and Southeast Asian Studies.[63] After his retirement from CUHK in 1996, Kao spent his six-month sabbatical leave at the Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering of Imperial College London; from 1997 to 2002, he also served as visiting professor in the same department.[64]

Kao was chairman and member of the Energy Advisory Committee (EAC) of Hong Kong for two years, and retired from the position on July 15, 2000.[65][66] Kao was a member of the Council of Advisors on Innovation and Technology of Hong Kong, appointed on April 20, 2000.[67] In 2000, Kao co-founded the Independent Schools Foundation Academy, which is located in Cyberport, Hong Kong.[68] He was its founding chairman in 2000, and stepped down from the board of the ISF in December 2008.[68] Kao was the keynote speaker at IEEE GLOBECOM 2002 in Taipei, Taiwan.[69] In 2003, Kao was named a Chair Professor by special appointment at the Electronics Institute of the College of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, National Taiwan University.[69] Kao then worked as the chairman and CEO of Transtech Services Ltd., a telecommunication consultancy in Hong Kong. He was the founder, chairman and CEO of ITX Services Limited. From 2003 to January 30, 2009, Kao was an independent non-executive director and member of the audit committee of Next Media.[70][71]

Awards

[edit]Kao received numerous awards such as the Nobel Prize in Physics,[72] Grand Bauhinia Medal, Marconi Prize, Prince Philip Medal, Charles Stark Draper Prize, Bell Award, SPIE Gold Medal, Japan International Award, Faraday Medal, and the James C. McGroddy Prize for New Materials.

Honours

[edit]- 1993: A Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE)[73]

- 2010: A Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (KBE)[14][74]

- 2010: The Grand Bauhinia Medal (GBM), Hong Kong[75]

Society and academy recognition

[edit]Honorary degrees

[edit]

| Country/Territory | Year | University | Honour | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1985 | Chinese University of Hong Kong | Doctor of Science honoris causa. | [90] | |

| 1990 | University of Sussex | Doctor of Science honoris causa. | [90] | |

| 1990 | National Chiao Tung University | Doctor of Engineering honoris causa. | [91][92] | |

| 1991 | Soka University | Degree of Honorary Doctor | [93] | |

| 1992 | University of Glasgow | Doctor of Engineering honoris causa. | [93] | |

| 1994 | Durham University | Honorary DCL | [94] | |

| 1995 | Griffith University | Doctor of the university | [93] | |

| 1996 | University of Padua | Doctor of Telecommunications Engineering honoris causa. | [95] | |

| 1998 | University of Hull | Doctor of Science honoris causa. | [96] | |

| 1999 | Yale University | Doctor of Science honoris causa. | [97][76] | |

| 2002 | University of Greenwich | Doctor of Science honoris causa. | [25] | |

| 2004 | Princeton University | Doctor of Science honoris causa. | [98] | |

| 2005 | University of Toronto | Doctor of Laws honoris causa. | [99] | |

| 2007 | Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications | Honorary Doctor | ||

| 2010 | University College London | Doctor of Science | [100] | |

| 2010 | University of Strathclyde | Honorary Degree | [101] | |

| 2011 | University of Hong Kong | Doctor of Science honoris causa. | [102] |

Awards

[edit]

Kao donated most of his prize medals to the Chinese University of Hong Kong.[73]

Namesakes

[edit]

- The minor planet 3463 Kaokuen, discovered in 1981, was named after Kao in 1996.

- 1996 (November 7): The north wing of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Science Center was named the Charles Kuen Kao Building.[86]

- 2009 (December 30): The landmark auditorium in the Hong Kong Science Park was named after Kao – the Charles K. Kao Auditorium.[114][115]

- 2010 (March 18): Professor Charles Kao Square, a square of the Independent Schools Foundation Academy[116]

- 2014 (September): Sir Charles Kao UTC (now known as BMAT STEM Academy) was opened.[117]

- 2014: Kao Data, a data center operator based on the former site of Sir Charles Kao's work on fibre optics cables, was founded.[118]

Others

[edit]- Featured in Science Museum London

- Hong Kong Affairs Adviser (May 1994 – June 30, 1997)[119][120]

- Advisor of the Macao Science and Technology Council[121]

- 1999: Asian of the Century, Science and Technology[11][122]

- 2002: Leader of the Year – Innovation Technology Category, Sing Tao, Hong Kong[73]

- October 21, 2002: Inducted into the Engineering Hall of Fame, the 50th Anniversary Issue, Electronic Design[123][124]

- January 3, 2008: Inducted into the Celebration 60, British Council's 60th anniversary in Hong Kong[125][126]

- November 4, 2009: Honorary citizenship, and the "Dr. Charles Kao Day" in Mountain View, California, U.S.A.[127]

- 2009: Hong Kong's Person of the Year[128]

- The Top 10 Asian Achievements of 2009 – No. 7[129]

- 2010 (February): Honoree, Committee of 100, U.S.A.[112]

- The 2010 OFC/NFOEC Conferences[e] were dedicated to Kao, March 23–25, San Diego, California, U.S.A.[130][131][132]

- May 14–15, 2010: Two sessions were dedicated to Kao at the 19th Annual Wireless and Optical Communications Conference (WOCC 2010), Shanghai, P.R. China.[133][134]

- May 22, 2010: Inducted into the memento archive of the 2010 Shanghai World Expo[135]

- Mid-2010: Hong Kong Definitive Stamp Sheetlet (No. 1), Hong Kong[136]

- March 25, 2011: Blue plaque unveiled in Harlow, Essex, U.K.[137]

- November 4, 2014: Gimme Fibre Day on Kao's birthday, FTTH Councils Global Alliance[138]

- November 4, 2021, Google celebrated Kao's birthday with a Google Doodle. The binary output in the graphic spells out 'KAO' when converted to ASCII.

Later life and death

[edit]Kao's international travels led him to opine that he belonged to the world instead of any country.[139][140] An open letter published by Kao and his wife in 2010 later clarified that "Charles studied in Hong Kong for his high schooling, he has taught here, he was the Vice-Chancellor of CUHK and retired here too. So he is a Hong Kong belonger."[141]

Pottery making was a hobby of Kao's. Kao also enjoyed reading Wuxia (Chinese martial fantasy) novels.[142]

Kao suffered from Alzheimer's disease from early 2004 and had speech difficulty, but had no problem recognising people or addresses.[143] His father suffered from the same disease. Beginning in 2008, he resided in Mountain View, California, United States, where he moved from Hong Kong in order to live near his children and grandchild.[6]

On October 6, 2009, when Kao was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his contributions to the study of the transmission of light in optical fibres and for fibre communication,[144] he said, "I am absolutely speechless and never expected such an honor."[145] Kao's wife Gwen told the press that the prize will primarily be used for Charles's medical expenses.[146] In 2010 Charles and Gwen Kao founded the Charles K. Kao Foundation for Alzheimer's Disease to raise public awareness about the disease and provide support for the patients.

In 2016, Kao lost the ability to maintain his balance. At the end-stage of his dementia he was cared for by his wife and intended not to be kept alive with life support or have CPR performed on him.[147] Kao passed away at Bradbury Hospice in Hong Kong on September 23, 2018, at the age of 84.[148][149][150][151]

Works

[edit]- Optical Fiber Technology; by Charles K. Kao. IEEE Press, New York, U.S.A.; 1981.

- Optical Fiber Technology, II; by Charles K. Kao. IEEE Press, New York, U.S.A.; 1981, 343 pages. ISBN 0-471-09169-3 ISBN 978-0-471-09169-1.

- Optical Fiber Systems: Technology, Design, and Applications; by Charles K. Kao. McGraw-Hill, U.S.A.; 1982; 204 pages. ISBN 0-07-033277-0 ISBN 978-0-07-033277-5.

- Optical Fibre (IEE materials & devices series, Volume 6); by Charles K. Kao. Palgrave Macmillan on behalf of IEEE; 1988; University of Michigan; 158 pages. ISBN 0-86341-125-8 ISBN 978-0-86341-125-0

- A Choice Fulfilled: the Business of High Technology; by Charles K. Kao. The Chinese University Press/ Palgrave Macmillan; 1991, 203 pages. ISBN 962-201-521-2 ISBN 978-962-201-521-0

- Tackling the Millennium Bug Together: Public Conferences; by Charles K. Kao. Central Policy Unit, Hong Kong; 48 pages, 1998.

- Technology Road Maps for Hong Kong: a Preliminary Study; by Charles K. Kao. Office of Industrial and Business Development, The Chinese University of Hong Kong; 126 pages, 1990.

- Nonlinear Photonics: Nonlinearities in Optics, Optoelectronics and fibre Communications; by Yili Guo, Kin S. Chiang, E. Herbert Li, and Charles K. Kao. The Chinese University Press, Hong Kong; 2002, 600 pages.

Notes

[edit]^ a: Kao's major task was to investigate light-loss properties in materials of optic fibers, and determine whether they could be removed or not. Hockham's was investigating light-loss due to discontinuities and curvature of fiber.

^ b: Some sources show around 1964,[152][153] for example, "By 1964, a critical and theoretical specification was identified by Dr. Charles K. Kao for long-range communication devices, the 10 or 20 dB of light loss per kilometer standard." from Cisco Press.[152]

^ c: In 1980, Kao was awarded the Gold Medal from American Armed Forces Communications and Electronics Association, "for contribution to the application of optical fiber technology to military communications".[50]

^ d: In the United States National Academy of Engineering Membership Website, Kao's country is indicated as "People's Republic of China".[81]

^ e: OFC/NFOEC – Optical Fiber Communication Conference and Exposition/National Fiber Optic Engineers Conference[132]

^ a: Kao's major task was to investigate light-loss properties in materials of optic fibers, and determine whether they could be removed or not. Hockham's was investigating light-loss due to discontinuities and curvature of fiber.

^ b: Some sources show around 1964,[152][153] for example, "By 1964, a critical and theoretical specification was identified by Dr. Charles K. Kao for long-range communication devices, the 10 or 20 dB of light loss per kilometer standard." from Cisco Press.[152]

^ c: In 1980, Kao was awarded the Gold Medal from American Armed Forces Communications and Electronics Association, "for contribution to the application of optical fiber technology to military communications".[50]

^ d: In the United States National Academy of Engineering Membership Website, Kao's country is indicated as "People's Republic of China".[81]

^ e: OFC/NFOEC – Optical Fiber Communication Conference and Exposition/National Fiber Optic Engineers Conference[132]

^ f: for making communication at optical frequencies practical by discovering, inventing, and developing the material, techniques and configurations for glass fibre waveguides and, in particular, for recognizing and proving by careful measurements in bulk glasses that silicon glass could provide the requisite low optical loss needed for a practical communication system

^ g: for contribution to the materials research and development that resulted in practical low loss optical fibres, one of the cornerstones of optical communications technology

^ h: in recognition of his pioneering work which led to the invention of optical fibre and for his leadership in its engineering and commercial realization; and for his distinguished contribution to higher education in Hong Kong

^ i: for pioneering research on wide-band, low-loss optical fibre communications

^ j: co-recipient with Robert D. Maurer and John B. MacChesney

^ k: for groundbreaking achievements concerning the transmission of light in fibres for optical communication

References

[edit]- ^ a b "List of Fellows". Archived from the original on June 8, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ a b "Fellows of the Royal Society". London: Royal Society. Archived from the original on March 16, 2015.

- ^ a b c d The Nobel Prize in Physics 2009 – Press Release. Nobel Foundation. October 6, 2009. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ a b "Prof Charles K. Kao". Department of Electronic & Electrical Engineering. University College London. September 24, 2018. Archived from the original on September 14, 2010. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ^ Hecht, Jeff (1999). City of Light, The Story of Fiber Optics. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 114. ISBN 0-19-510818-3.

- ^ a b Mesher, Kelsey (October 15, 2009). "The legacy of Charles Kao". Moun. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ^ dpa (October 6, 2009). "PROFILE: Charles Kao: 'father of fiber optics,' Nobel winner". Earthtimes. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ^ Record control number (RCN):31331 (October 7, 2009). "'Father of Fibre Optics' and digital photography pioneers share Nobel Prize in Physics". Europa (web portal). Archived from the original (cfm) on January 25, 2008. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Bob Brown (Network World) (October 7, 2009). "Father of fiber-optics snags share of Nobel Physics Prize". CIO. cio.com.au. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ^ a b "The father of optical fiber – Narinder Singh Kapany/Prof. C. K. Kao" (in Chinese and English). networkchinese.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2009. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ a b Erickson, Jim; Chung, Yulanda (December 10, 1999). "Asian of the Century, Charles K. Kao". Asiaweek. Archived from the original on July 21, 2002. Retrieved December 24, 2009.

- ^ "Prof. Charles K Kao speaks on the impact of IT in Hong Kong". The Open University of Hong Kong. January 2000. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2009.

- ^ The Nobel Prize in Physics 2009. Nobel Foundation. October 6, 2009. Archived from the original on October 8, 2009. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- ^ a b "No. 59446". The London Gazette (1st supplement). June 12, 2010. p. 23.

- ^ 高錕. 香港百人 (in Cantonese, Chinese, and English). Asia Television. 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kao, Charles K. (2005). 潮平岸闊 – 高錕自傳 [A Time And A Tide: Charles K. Kao – A Memoir]. Translated by 許迪鏘 (First ed.). Hong Kong: Joint Publishing. ISBN 978-962-04-3444-0.

- ^ a b c Fan, Yanping (范彦萍) (October 10, 2009). 诺贝尔得主高锟的堂哥回忆:他兒时国学功底很好 [Interview of Kao's cousin]. Youth Daily (in Chinese (China)). Shanghai. Archived from the original on October 11, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2009 – via eastday.com.

- ^ 高錕. 傑出華人系列 (documentary and oral history) (in Cantonese, Chinese, and English). Radio Television Hong Kong. 2000. Event occurs at 12:00 to 13:00. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ^ 陶家骏 (June 1, 2008). 著名女教育家陶玄 [Famous Female Educator Tao Xuan]. 绍兴县报 [Shaoxing County News] (in Chinese). Archived from the original on March 13, 2012. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- ^ 「光纖之父」高錕離世 享年84歲 (16:56). Online instant news section. Ming Pao (in Chinese (Hong Kong)). Hong Kong: Media Chinese International. September 23, 2018. Archived from the original on September 23, 2018. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ^ 【高錕病逝】展覽懷緬光纖之父 會考證書曝光數學只攞Credit. Apple Daily (in Chinese (Hong Kong)). September 29, 2018. Archived from the original on September 30, 2018. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ^ "Prominent Old Boys - St. Joseph's College". www.sjc.edu.hk. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "Facebook". www.facebook.com. Retrieved August 3, 2024.

- ^ a b c uniquekey. "Nobel Laureate in Physics - Professor Charles Kuen KAO". hklaureateforum.org. Retrieved August 3, 2024.

- ^ a b "meantimealumni Spring 2005" (PDF). University of Greenwich. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 9, 2011. Retrieved October 7, 2009.

- ^ "Sir Charles Kao – Alumni | University of Greenwich". Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ University of Michigan Law School: Alphabetical List with Year of Law School Graduates Archived March 19, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 高君湘_法律学人_雅典学园. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved October 7, 2009.

- ^ 中国近代法律教育与中国近代法学. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011.

- ^ 参加南社纪念会姓氏录 [List of Nan Society member] (in Chinese). 南社研究網 [Research of Nan Society]. Archived from the original on November 21, 2008. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ 高平子先生简介 (in Chinese). 青岛天文网--中国科学院紫金山天文台青岛观象台/青岛市天文爱好者协会. February 8, 2006. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ "Lunar Crater Statistics". NASA. Archived from the original on August 13, 2009. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ 高锟个人简历 [The biography of Charles K. Kao] (in Chinese). chinanews.com.cn. October 6, 2009. Archived from the original on October 8, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- ^ 高錕. 傑出華人系列 (documentary and oral history) (in Cantonese, Chinese, and English). Radio Television Hong Kong. 2000. Event occurs at around 20:00. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ^ Midwinter, John (June 2021). "Sir Charles Kuen Kao. 4 November 1933—23 September 2018". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 70: 211–224. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2020.0006. ISSN 0080-4606.

- ^ "Draper Prize". draper.comg. Archived from the original on February 14, 2010. Retrieved November 4, 2009. "Charles Kao is credited for first publicly proposing the possibility of practical telecommunications using fibers in the 1960s."

- ^ Montgomery, Jeff D. (March 22, 2002). "Chapter 1 – History of Fiber Optics". In DeCusatis, Casimer (ed.). Fiber optic data communication: technological trends and advances (1st ed.). Academic Press. 1.3.1. Long Road to Low-Loss Fiber (pp. 9–16). ISBN 978-0-12-207891-0.

- ^ a b "Charles Kao's Notes made in 1963 – Set A". March 23, 2016.

- ^ a b Jeff Hecht. "A Short History of Fiber Optics". Archived from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved October 8, 2010.

- ^ a b "Communication pioneers win 2009 physics Nobel". IET. October 7, 2009. Archived from the original on October 13, 2009. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Fiber Types in Gigabit Optical Communications" (PDF). Cisco Systems, USA. April 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved November 3, 2009.

- ^ Kao, K. C.; Hockham, G. A. (1966). "Dielectric-fibre surface waveguides for optical frequencies". Proc. IEE. 113 (7): 1151–1158. doi:10.1049/piee.1966.0189.

- ^ Midwinter, John (2021). "Sir Charles Kuen Kao. 4 November 1933—23 September 2018". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 70: 211–224. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2020.0006. ISSN 0080-4606.

- ^ Hecht, Jeff (March 1, 2019). "The Remarkable Fiber Optic Vision Of Charles Kao". Optics & Photonics News. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ "Sir Charles Kao: Fibre optics genius passes away". BBC. (26 September 2018). Retrieved 21 May 2020

- ^ Maryanne C. J. Large; Leon Poladian; Geoff Barton; Martijn A. van Eijkelenborg. (2008). Microstructured Polymer Optical Fibres. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-31273-6. Page 2

- ^ "Chapter 1.1 – The Evolution of Fibre Optics" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 31, 2011. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ a b "2009 Nobel Prize in Physics – Scientific Background: Two revolutionary optical technologies – Optical fiber with high transmission" (PDF). Nobelprize.org. October 6, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 22, 2009. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- ^ 1999 Charles Stark Draper Award Presented Archived May 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine "Kao, who was working at ITT's Standard Telecommunications Laboratories in the 1960s, theorized about how to use light for communication instead of bulky copper wire and was the first to publicly propose the possibility of a practical application for fiber-optic telecommunication."

- ^ a b c d e f g "Charles Kuen Kao" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 14, 2011. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ a b c "A Fiber-Optic Chronology (by Jeff Hecht)". Archived from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved November 3, 2009.

- ^ Tamura, Yoshiaki; Sakuma, Hirotaka; Morita, Keisei; Suzuki, Masato; Yamamoto, Yoshinori (2017). "Lowest-Ever 0.1419-dB/km Loss Optical Fiber". Optical Fiber Communication Conference: Th5D.1. ISBN 978-1-943580-24-8.

- ^ Technology of Our Times: People and Innovation in Optics and Optoelectronics (SPIE Press Monograph Vol. PM04), by Frederick Su; SPIE Publications (July 1, 1990); ISBN 0-8194-0472-1, ISBN 978-0-8194-0472-5. Page 82–86, Terabit Technology, by Charles K. Kao.

- ^ "Water resistant high strength fibers (United States Patent 4183621)" (PDF). January 15, 1980 [date filed: December 29, 1977]. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

- ^ "Guiding light". May 1989. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 16, 2009. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- ^ "1, A Global Footprint" (PDF). Building the Global Fiber Optics Superhighway (Free Abstract). Springer USA. May 8, 2007. ISBN 978-0-306-46505-5. Retrieved November 3, 2009.

ISBN 978-0-306-46979-4 (Online)

[permanent dead link] - ^ Nim Cheung, ed. (March 2010). "IEEE Communications Magazine SOCIETY NEWS" (PDF). CISOC. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ CUHK Handbook Archived December 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Annual Report 2002, Varitronix International Limited" (PDF). Varitronix International Ltd. April 3, 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 17, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

- ^ 精電國際有限公司 (PDF) (in Chinese and English). 精電國際有限公司. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 17, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

- ^ "President of ASAIHL". ASAIHL. Archived from the original on July 4, 2015. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

- ^ "Kao Gift Will Help Build Ties Between Asia and Yale". Yale Bulletin and Calendar, News Stories. June 24 – July 22, 1996. Archived from the original on June 11, 2009. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ^ "Fellowships and research support" (php). The Councils on East Asian and Southeast Asian Studies at Yale University. Archived from the original on July 2, 2010. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ^ "Research Awards and Honours". Imperial College London Department of Electric and Electronic Engineering. 2009. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved December 24, 2009.

- ^ "Appointment of Chairman and Members of the Energy Advisory Committee". Hong Kong Government. August 11, 2000. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved November 3, 2009.

- ^ "EPD – Advisory Council on the Environment". Environmental Protection Department, The Government of Hong Kong SAR. April 28, 2006. Archived from the original on June 11, 2011. Retrieved November 3, 2009.

- ^ "The Council of Advisors on Innovation & Technology appointed" (PDF). The Government of Hong Kong SAR. April 20, 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 22, 2011. Retrieved November 3, 2009.

- ^ a b "Founding Chairman receives 2009 Nobel Prize for Physics" (php). The ISF Academy. Archived from the original on February 28, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Charles K. Kao, NTU's former chair professor by special appointment, wins the Nobel Prize in Physics". National Taiwan University. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

- ^ 壹传媒(00282)高锟辞任独立非执董及审核委员,黄志雄接任 (in Chinese). jrj.com.cn. July 2, 2009. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

- ^ 中研院士高錕 勇奪物理獎. Apple Daily (in Chinese). Taiwan. October 7, 2009. Archived from the original on October 17, 2009. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

- ^ "Charles K. Kao". Nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on May 13, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Medals Donated to CUHK by Professor Kao". The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Archived from the original on December 19, 2009. Retrieved December 24, 2009.

- ^ JILL LAWLESS (June 13, 2010). "Right royal boost for Zeta". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on June 15, 2010. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ "306 people to receive honours". The Government of Hong Kong SAR. July 1, 2010. Retrieved July 1, 2010. [dead link]

- ^ a b "Yale Bulletin and Calendar - News". archives.news.yale.edu. Archived from the original on July 10, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "OSA Nobel Laureates". Optical Society of America (OSA). Archived from the original (aspx) on October 29, 2009. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ^ "Fellows – Charles K. Kao". IEEE. Archived from the original on April 6, 2009. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ^ "Membership – Hong Kong Computer Society Annual Report 2008-2009". Hong Kong Computer Society. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ^ "List of Distinguished Fellows". The Hong Kong Computer Society. Archived from the original (asp) on May 7, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Dr. Charles K. Kao". United States National Academy of Engineering. 1990. Archived from the original (nsf) on May 28, 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ^ "Charles K. Kao". Academia Sinica. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ a b The HKIE Secretariat (October 7, 2009). "The HKIE – News". The HKIE. Archived from the original (asp) on July 21, 2011. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ^ 高锟:厚道长者 毕生追求 (shtm) (in Chinese). news.sciencenet.cn (科學網·新聞). October 14, 2009. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ^ "The HKIE – News". The Hong Kong Institute of Engineers (HKIE). October 7, 2009. Archived from the original (asp) on July 21, 2011. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ^ a b "Content of Chinese University Alumni Magazine" 高錕校長榮休誌念各界歡送惜別依依. CUHK Alumni website (in Chinese (Hong Kong)). CUHK. September 1996. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- ^ "Graduate Research Studies Newsletter" (PDF). City University of Hong Kong. February 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 5, 2011. Retrieved April 2, 2010.

- ^ Midwinter, John (2020). "Sir Charles Kuen Kao. 4 November 1933—23 September 2018". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 69: 211–224. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2020.0006. S2CID 226291122.

- ^ "e-Newsletter, Alumni at Queen Mary, University of London". Qmw.ac.uk. Retrieved October 26, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Honorary Professors and Emeritus Professors". Chinese University of Hong Kong. n.d. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ^ 國立交通大學 公共事務委員會 名譽博士名單 (php) (in Chinese). National Chiao Tung University. Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ^ 校史 – 國立交通大學時期|民國六十八年(一九七九)以後 (in Chinese). National Chiao Tung University (NCTU). Archived from the original on March 26, 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ^ a b c "CHARLES KUEN KAO" (PDF).

- ^ "Honorary Degrees" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 21, 2007. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ^ Università degli Studi di Padova – Honoris causa degrees Archived September 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Honorary graduates 2 – University of Hull". Archived from the original on December 19, 2016.

- ^ "Yale Honorary Degree Recipients". Archived from the original on May 21, 2015.

- ^ "Princeton University – Facts & Figures". Archived from the original on September 21, 2008. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- ^ "Engineering a World of Possibilities" (PDF). University of Toronto Applied Science & Engineering. Spring 2006. Retrieved October 26, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "UCL Fellows and Honorary Fellows announced". June 17, 2010. Retrieved June 19, 2010.

- ^ "Honorary degree for broadband pioneer". September 24, 2010. Archived from the original on September 30, 2010. Retrieved September 27, 2010.

- ^ "HKU Honorary Graduates - Graduate Detail" (Press release). The University of Hong Kong. 2011 [circa]. Archived from the original on September 25, 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

- ^ "CIE-USA ANNUAL AWARDS" (PDF) (in English and Chinese). CIE-USA. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 25, 2011. Retrieved April 2, 2010.

- ^ "Prize Recipient". Archived from the original on August 28, 2016. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ "Gold Medal Award - SPIE". Archived from the original on May 24, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- ^ "HKIE" Press Releases – 香港工程師學會榮譽大獎、會長特設成就獎及傑出青年工程師獎2006 [The HKIE Gold Medal Award, the President's Award & Young Engineer of the Year Award 2006] (in Chinese (Hong Kong)). The Hong Kong Institute of Engineers.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2009". NobelPrize.org. Archived from the original on September 25, 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

- ^ "Research Highlights". IEEE Photonics Society. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved October 16, 2010.

- ^ 美洲中國工程師學會2010年工程獎章得獎名單出爐(2/27) (asp) (in Chinese and English). AAEOY. February 23, 2010. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- ^ 华裔科学家高锟荣获影响世界华人大奖 (in Chinese). Xinhua News Agency. March 11, 2010. Archived from the original on March 16, 2010. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ^ 华裔科学家高锟荣获影响世界华人大奖 (shtml) (in Chinese). Phoenix Television. March 11, 2010. Archived from the original on March 26, 2010. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ^ a b Jane Leung Larson (February 2010). "2009 Nobel Laureate Charles Kao among Committee of 100 Honorees in San Francisco". Committee of 100. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- ^ "Vodafone and Sir Charles Kao recognised in FTTH Awards 2014" (PDF). FTTH Council Europe. February 20, 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 22, 2014. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- ^ 香港两座建筑物将以高锟及饶宗颐名字命名(图) [Two landmark buildings in Hong Kong are named after Charles K. Kao and Rao Zongyi (with photos)] (shtml) (in Chinese (China)). Ifeng News. December 30, 2009. Archived from the original on October 6, 2010. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- ^ "Hong Kong to name building after Nobel laureate Charles Kao". chinaview.cn. December 31, 2009. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- ^ "The ISF Academy Newsletter 2009/10 March 2010 Issue 3" (PDF). Independent Schools Foundation Academy. March 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 September 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ "Sir Charles Kao UTC". Archived from the original on July 14, 2014.

- ^ "Kao Data". Archived from the original on April 20, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ A chat with vice-chancellor Kao Archived December 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, by Midori Hiraga

- ^ The Standard: The day Nobel winner lost mic Archived June 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ XinhuaNet News: Macao chief congratulates Nobel Prize winner Charles Kao Archived October 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Asian of the Century". Asiaweek. 1999. Archived from the original on October 15, 2009. Retrieved December 24, 2009.

- ^ "Electronic Design, 50th Anniversary Issue". Electronic Design. October 21, 2002. Archived from the original on May 5, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "ED Hall of Fame 2002 INDUCTEES" (PDF). Electronic Design. October 21, 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 26, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "Enter the Creative Dragon Feature" (PDF). AlumniNews London Business School. January–March 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2009. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "British Council Celebrates 60 Years in Hong Kong" (PDF). Hong Kong: British Council. January 3, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 6, 2011. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "City Press Release: Mountain View Honors Dr. Charles Kao for Being Awarded the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physics". Office of the City Manager, Mountain View, California. October 27, 2009. Archived from the original (asp) on February 29, 2012. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- ^ "Nobel laureate Charles Kao is named Hong Kong's Person of Year". Earthtimes. January 4, 2010. Archived from the original on September 10, 2012. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- ^ Evangeline Cafe (December 30, 2009). "The top 10 Asian achievements of 2009". Northwest Asian Weekly. Archived from the original on January 8, 2011. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- ^ "OFC/NFOEC 2010 To Be Dedicated To Nobel Laureate Charles Kao" (mvc). Photonics Online. January 15, 2010. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved January 20, 2009.

- ^ "OFC/NFOEC 2010 Announces Plenary Session Speaker Lineup". Yahoo! Finance. January 21, 2010. Retrieved January 20, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Angela Stark. "OFC/NFOEC 2010 to be Dedicated to Nobel Prize Winner and Industry Pioneer Charles Kao". OFC/NFOEC Press Releases. Archived from the original (aspx) on July 9, 2010. Retrieved January 20, 2009.

- ^ "The 19th Annual Wireless and Optical Communications Conference (WOCC 2010)". WOCC 2010. 2010. Archived from the original on April 17, 2010. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ 康宁公司在华开展光纤发明40周年庆祝活动 (in Chinese). 美通社(亚洲). May 18, 2010. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ 《世界百位名人谈上海世博》首发 (in Chinese). Xinhua News Agency. May 23, 2010. Archived from the original on June 21, 2010. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ "Hongkong Post Stamps – Hong Kong Stamps". Hongkong Post. Archived from the original on March 30, 2010. Retrieved Apr 8, 2010.

- ^ "Harlow Nobel Prize winner to be commemorated in town centre". HarlowStar. March 25, 2011. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ^ "Gimme Fibre Day - 4 November". Fibre to the Home Council Europe. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- ^ 高錕. 傑出華人系列 (documentary and oral history) (in Cantonese, Chinese, and English). Radio Television Hong Kong. 2000. Event occurs at around 38:00. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

我對每一個國家,每一個種族感情都差不多。。。。。。我是以人為主,不是以國家或種族為主。。。。。。我變成了世界中間的一部份,不是任何國家的一部份。

- ^ Kao, Charles; Kao, May Wan (October 13, 2009). "Professor and Mrs Charles K. Kao wish to express their gratitude to their friends, all staff, students and alumni at CUHK, members of the media, and the people of Hong Kong, by the following Open Letter" (Press release). Chinese University of Hong Kong. Archived from the original on October 16, 2009. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

Charles Kao was born in Shanghai, China, did his primary research in 1966 at Standard Telecommunication Laboratories (STL) in Harlow, UK, followed through with work in the USA at ITT, over the following 20 years, to develop fiber optics into a commercial product and finally came to CUHK, Hong Kong in 1987 to pass on his knowledge and expertise to a new generation of students and businessmen. Charles really does belong to the world!

- ^ Kao, Charles K.; Kao, May Wan (February 5, 2010). "Message from Prof. and Mrs. Charles K. Kao (5 February 2010)" (Press release). Chinese University of Hong Kong. Archived from the original on December 27, 2010. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ^ 记者探访"光纤之父"高锟:顽皮慈爱的笑. QQ.com News (in Chinese (China)). October 8, 2009. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ 港媒年初传高锟患老年痴呆症 妻称老人家记性差. Ifeng.com (in Chinese (China)). October 2009. Archived from the original on October 9, 2009. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ "Physics 2009". Nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on March 31, 2012. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ^ Ian Sample, science correspondent (October 6, 2009). "Charles Kuen Kao, George Smith and Willard Boyle win Nobel for physics". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 8, 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ ○九教育大事(二) 高錕獲遲來的諾獎. Sing Tao Daily (in Chinese (Hong Kong)). HK Yahoo! Archive. January 2, 2010. Archived from the original on January 7, 2010.

- ^ "" Nobel winner wants to die in peace at home, wife says, as she urges Hong Kong to change culture on end-of-life care", South China Morning Post Newspaper 2016". July 10, 2016. Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- ^ Chiu, Peace; Singh, Abhijit; Lam, Jeffie (September 23, 2018). "Hong Kong mourns passing of Nobel Prize winner and father of fiber optics, Charles Kao, 84". South China Morning Post. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on September 23, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ^ 諾獎得主光纖之父高錕逝世 慈善基金:最後心願助腦退化病人. Ming Pao (in Chinese (Hong Kong)). Hong Kong: Media Chinese International. September 24, 2018. Archived from the original on September 25, 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

- ^ "In memory of Sir Charles K. Kao (1933-2018)" (Press release). Hong Kong: Charles K. Kao Foundation for Alzheimer's Disease. September 23, 2018. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

- ^ Ives, Mike (September 24, 2018). "Charles Kao, Nobel Laureate Who Revolutionized Fiber Optics, Dies at 84". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 24, 2018. Retrieved September 26, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Vivek Alwayn (April 23, 2004). "Fiber-Optic Technologies – A Brief History of Fiber-Optic Communications". Cisco Press. Archived from the original on November 8, 2007. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- ^ a b Mary Bellis. "The Birth of Fiber Optics". inventors.about.com. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved December 15, 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- Kao, Charles (1982). Optical Fibre Systems: Technology, Design and Application. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Inc., US. ISBN 978-0070332775.

- Hecht, Jeff (1999). City of Light, The Story of Fiber Optics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510818-7.

- Kao, K. C.; Hockham, G. A. (1966). "Dielectric-fibre surface waveguides for optical frequencies". Proc. IEE. 113 (7): 1151–1158. doi:10.1049/piee.1966.0189.

- Kao, K. C.; Davies, T. W. (1968). "Spectrophotometric Studies of Ultra Low Loss Optical Glasses – I: Single Beam Method". Journal of Physics E. 2 (1): 1063–1068. Bibcode:1968JPhE....1.1063K. doi:10.1088/0022-3735/1/11/303. PMID 5707856.

- K. C. Kao (June 1986), "1012 bit/s Optoelectronics Technology", IEE Proceedings 133, Pt.J, No 3, 230–236. doi:10.1049/ip-j.1986.0037

- 高錕. 傑出華人系列 (documentary and oral history) (in Cantonese, Chinese, and English). Radio Television Hong Kong. 2000. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- "Oral-History:Charles Kao". Engineering and Technology History Wiki (oral history transcript). Interview Conducted by Robert Colburn. September 26, 2018 [interview conducted in 2004]. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Kao, Charles K. (2010). A Time and A Tide: Charles K. Kao ─ A Memoir (autobiography). Chinese University Press. ISBN 9789629969721.

- Kao, Charles K. (2005). 潮平岸闊——高錕自傳 [A Time And A Tide: Charles K. Kao ─ A Memoir] (autobiography) (in Chinese (Hong Kong)). Translated by 許迪鏘. Joint Publishing (Hong Kong). ISBN 978-962-04-3444-0.

External links

[edit]- Optical Fibre History at STL

- Charles K. Kao on Nobelprize.org including the Nobel Lecture 8 December 2009 Sand from centuries past; Send future voices fast

- BBC: Lighting the way to a revolution

- Mountain View Voice: The legacy of Charles Kao Archived February 15, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- Man who lit up the world – Professor Charles Kao CBE FREng Ingenia, Issue 43, June 2010

- 1933 births

- 2018 deaths

- Academics of Imperial College London

- Academics of Queen Mary University of London

- Alumni of University of London Worldwide

- Alumni of the University of London

- Alumni of the University of Greenwich

- Alumni of University College London

- American electrical engineers

- American Nobel laureates

- American people of Hong Kong descent

- American physicists

- American people of Chinese descent

- British electrical engineers

- British emigrants to the United States

- British Nobel laureates

- British physicists

- Chinese University of Hong Kong people

- Draper Prize winners

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Fellows of the Royal Academy of Engineering

- Fellows of the IEEE

- Fellows of the Institution of Engineering and Technology

- Fiber-optic communications

- Hong Kong Affairs Advisors

- Hong Kong electrical engineers

- Hong Kong emigrants to England

- Hong Kong Nobel laureates

- Hong Kong physicists

- Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire

- Members of Academia Sinica

- Members of the European Academy of Sciences and Arts

- Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences

- Members of the United States National Academy of Engineering

- Foreign members of the Chinese Academy of Sciences

- Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom

- Nobel laureates in Physics

- People with Alzheimer's disease

- Recipients of the Grand Bauhinia Medal

- Physicists from Shanghai

- Vice-chancellors of the Chinese University of Hong Kong

- Yale University faculty

- Yale University fellows

- Educators from Shanghai

- SPIE

- ITT Inc. people

- Chinese emigrants to Hong Kong

- Chinese Roman Catholics

- Hong Kong Roman Catholics

- American Roman Catholics

- Optical engineers

- Optical physicists