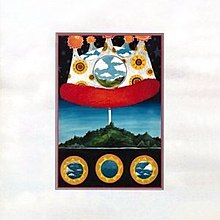

Music from the Unrealized Film Script: Dusk at Cubist Castle

| Music from the Unrealized Film Script: Dusk at Cubist Castle | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | August 6, 1996 | |||

| Studio | Pet Sounds, Denver | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 74:05 | |||

| Label | Flydaddy | |||

| Producer | Robert Schneider | |||

| The Olivia Tremor Control chronology | ||||

| ||||

Music from the Unrealized Film Script: Dusk at Cubist Castle is the debut studio album by the American band the Olivia Tremor Control, released on August 6, 1996, by Flydaddy Records. It is an eclectic album that encompasses a variety of genres, including indie pop, neo-psychedelia, and psychedelic pop. The Olivia Tremor Control were influenced by bands of 1960s and 1970s, such as the Beach Boys and the Beatles, as well as experimental musicians like John Cage. Dusk at Cubist Castle purports to be the soundtrack to an unfinished film, and the lyrics focus on surrealist imagery.

The Olivia Tremor Control was formed in Athens, Georgia, and the line-up comprised Bill Doss, Will Cullen Hart, Eric Harris, and John Fernandes. Doss and Hart had been writing songs for a studio album as early as 1993, and Dusk at Cubist Castle was recorded at Pet Sounds Studio in Denver, Colorado. Childhood friend Robert Schneider served as the producer, and the recording sessions featured several other musicians, including Jeff Mangum and Julian Koster. Dusk at Cubist Castle received positive reviews from critics, and Pitchfork ranked it as one of the best albums of the 1990s.

Background and recording

[edit]The Olivia Tremor Control originated as a psychedelic band called Cranberry Lifecycle.[1] This band was formed in Ruston, Louisiana in the late 1980s, by high school friends Will Cullen Hart and Jeff Mangum.[2] After graduating from high school, the two moved to Athens, Georgia, and reworked Cranberry Lifecycle songs under the name Synthetic Flying Machine.[3] Fellow Rustonian Bill Doss joined in 1993, and the lineup consisted of Hart on electric guitar, Doss on bass guitar, and Mangum on drums. The band gained a small following due in part to the psychedelic-infused music, which differed from the prevalent grunge sound in the city.[4] Mangum left the group shortly after its formation, as he wanted to focus on a solo project that would eventually become Neutral Milk Hotel.[5] Doss and Hart then decided to rename the group to the Olivia Tremor Control.[6] Mangum suggested the name, which was intended to be a surreal sounding phrase with no further meaning.[7][a]

After the release of the first Olivia Tremor Control extended play —California Demise–in 1994, Hart moved to Denver, while Doss moved to New York City to play in the band Chocolate USA.[9] By 1996, Doss was losing interest in Chocolate USA, and wanted to record more music with Hart. The two reconvened in Athens, and recruited multi-instrumentalists John Fernandes and Eric Harris.[9][10] With this lineup, the Olivia Tremor Control went to Denver to record their first studio album. Robert Schneider, a childhood friend of Doss and Hart, served as the producer, and the album was recorded at Pet Sounds Studio.[10]

Doss and Hart had been recording songs on 4-track tapes for a studio album as early as 1993.[10] Doss' ideas were more pop friendly while Hart wrote more experimental songs.[10] Their dichotomous partnership during this era drew some comparisons to Lennon–McCartney of the Beatles, although Stereogum noted that both Fernandes and Harris retained creative input.[10] Schneider played on several songs, and other musicians like Jeff Mangum and Julian Koster also contributed. Hart noted that the recording sessions were busy, and estimated that at least eight people played guitar on the song "The Opera House."[10]

Composition

[edit]Dusk at Cubist Castle is a 74 minute double album comprising 27 songs.[11] Critics have described Dusk at Cubist Castle as an eclectic album that encompasses a variety of genres, including indie pop, neo-psychedelia, and psychedelic pop.[12][13] Jason Ankeny of AllMusic also notes the influence of other genres, such as krautrock, noise music, and folk rock.[14] While discussing the music as a whole, Stereogum described Dusk at Cubist Castle as a "maximalist analog production, sonically distended with so many different ideas that it sounds a little different every time you hear it."[10] The album purports to be the soundtrack to an unfinished film titled Dusk at Cubist Castle. However, no such film ever existed.[15]

Some critics have found the first half of Dusk at Cubist Castle to be the more immediate and easily accessible than the rest of the album.[11][13] Zachary Houle of PopMatters describes these songs as "Beach Boys meets late-period Beatles in its take on psychedelica".[11] "Jumping Fences" and "Define a Transparent Dream" are among the more notable songs that are indebted to 1960s and 1970s bands.[11][13][16] Houle compares "Jumping Fences" to a lost Badfinger song, while "Define a Transparent Dream" is reminiscent of David Bowie's "Changes."[11] Paul Thompson of Pitchfork does note that while the Olivia Tremor Control are heavily influenced by these bands, they interpose their songs with what he describes as: "weird left turns, with hooks that seem to bubble out of nowhere before receding into themselves."[13]

The second half of the album features more experimental songs, influenced by drone music and musique concrète.[11][10] When asked about the inclusion of these experimental songs, Fernandes said: "We wanted to change the way people listen to music ... Make people who love the Beatles also appreciate John Cage."[10] An example of this experimentation is the suite of ten consecutive songs all titled "Green Typewriters".[11] The eighth song in the suite is nearly ten minutes, and is a drone piece that features the sound of standing bells, typewriter keys, passing cars, and dripping water.[11][10] The album's title track is a similar drone piece, which Houle compared to the music of a haunted house.[11] Houle does note that not every song on the second half of the album is experimental, and highlights the final song "NYC-25" as a "jaunty country rock number that leaves an aftertaste of the Beatles yet again."[11]

Dusk at Cubist Castle focuses on surrealist imagery, in particular dreams.[12][13] Hart described the album as "dream music for your mind."[17] Thompson identifies the opening song "The Opera House" as an example of lyrical surrealism, as it mentions going to the movie theater to simply watch the actors move their mouths.[13] Other topics found throughout the album include a dream that features model headshots of Gertrude Stein, and a cosmonaut who is too transfixed on the thoughts in his mind to speak.[12][13] Many of the lyrics found throughout Dusk at Cubist Castle are sincere and happy, which Stereogum noted was different from the prevailing ethos of 1990s indie music, which focused on disillusionment and irony.[10] In a 1997 interview, Doss said he wanted the Olivia Tremor Control's music to instill a sense of "mystery or happiness" in listeners. "I'm sending out a positive message, because the world needs it ... We're reaching for something that's hard to explain."[18]

Release and reception

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Alternative Press | 4/5[19] |

| The Austin Chronicle | |

| The A.V. Club | A[21] |

| NME | 8/10[22] |

| Pitchfork | 9.1/10[13] |

| Q | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Spin | 7/10[25] |

| Tiny Mix Tapes | 4.5/5[26] |

Dusk at Cubist Castle was released on August 6, 1996, by Flydaddy Records.[10][27] Early CD pressings included a second album titled Explanation II: Instrumental Themes and Dream Sequences.[28] This album contains nine ambient songs, and in the liner notes it is suggested to play the two albums in synchronicity, as this would create quadraphonic sound.[11][b] The songs "The Opera House" and "Jumping Fences" were released as singles.[28] To promote the album, the Olivia Tremor Control served as an opener for Beck, and toured with Gorky's Zygotic Mynci in 1998.[29] Keyboardist Peter Erchick was brought on as the fifth band member while on tour.[30]

In a contemporary review of Dusk at Cubist Castle for NME, Tom Cox called the Olivia Tremor Control "experts at combining the absurd with the uplifting."[22] Alternative Press praised the band's "perfect hooks and strong, melodic singing",[19] while Jason Cohen of The Austin Chronicle remarked that, with the exception of the "random bursts and transient noise" of "Green Typewriters", Dusk at Cubist Castle is "an embarrassment of pop riches, a mildly psychedelic, lavishly melodic quasi-masterpiece."[20] Spin reviewer Chuck Stephens gave qualified praise, crediting the group for avoiding "parodic excess or overproduced pabulum" but much preferring the album's "silly pop songs", opining that "when OTC stop shaking ... the mind candy starts to melt."[25] Q's Johnny Black found the album largely derivative of 1960s acts such as the Beach Boys and the Beatles, though overall successful at reinterpreting their sounds "through a '90s filter".[23] The album ranked at number 37 in The Village Voice's year-end Pazz & Jop critics' poll.[31]

Writing in retrospect for Pitchfork, Paul Thompson lauded Dusk at Cubist Custle as a "stately, sumptuous, and slightly otherworldly" album "brimming with immaculate hooks and queries bound for the cosmos".[13] In 2003, it was ranked at number 39 on the website's list of the best albums of the 1990s.[32] In the 2004 Rolling Stone Album Guide, Roni Sarig stated that despite "a serious need for editing", the album stands as the Olivia Tremor Control's "most cohesive recording, revealing a band clearly capable of creating solid retro-pop songs."[24] Jason Ankeny, in his review for AllMusic, likened it to the Beatles' 1968 self-titled album in sound and "unfettered creativity", dubbing it "an incredible facsimile".[14] Tiny Mix Tapes said that while Dusk at Cubist Candle draws "unabashedly ... from obvious sources", its primary strength "lies not in inventiveness or experimentation (which is not to say it lacks any), but in its ability to strike a dear balance between the temptation of emulating the artists so highly revered, and the exigency and essential need to forge a new sound."[26]

Track listing

[edit]All songs written by The Olivia Tremor Control.

- "The Opera House" – 3:12

- "Frosted Ambassador" – 1:02

- "Jumping Fences" – 1:52

- "Define a Transparent Dream" – 2:49

- "No Growing (Exegesis)" – 3:00

- "Holiday Surprise 1, 2, 3" – 6:11

- "Courtyard" – 2:57

- "Memories of Jacqueline 1906" – 2:15

- "Tropical Bells" – 1:40

- "Can You Come Down with Us?" – 2:18

- "Marking Time" – 4:28

- "Green Typewriters" – 2:22

- "Green Typewriters" – 0:24

- "Green Typewriters" – 0:59

- "Green Typewriters" – 2:11

- "Green Typewriters" – 1:10

- "Green Typewriters" – 0:38

- "Green Typewriters" – 1:38

- "Green Typewriters" – 9:39

- "Green Typewriters" – 1:21

- "Green Typewriters" – 2:39

- "Spring Succeeds" – 2:25

- "Theme for a Very Delicious Grand Piano" – 0:57

- "I Can Smell the Leaves" – 1:50

- "Dusk at Cubist Castle" – 7:35

- "The Gravity Car" – 1:45

- "NYC-25" – 4:39

Personnel

[edit]Instrumentation, vocals and production by The Olivia Tremor Control:

- Bill Doss – instrumentation, vocals, production, artwork and design

- W. Cullen Hart – instrumentation, vocals, production, artwork and design

- Eric Harris – instrumentation, vocals, production

- John Fernandes – instrumentation, vocals, production

Additional instrumentation and production by The Elephant 6 Orchestra:

- Robert Schneider – Tibetan prayer bowl, bass,[ambiguous] vocals, melodica, co-production, engineering

- Jeff Mangum – chanter pipe, slide guitar, vocals, melodica, piano and space bubbles

- Julian Koster – bowed electric guitar, mallet struck acoustic guitar and the singing saw

- Steve Jacobek – trumpet

- Rick Benjamin – trombone

Notes

[edit]- ^ Doss offered a different explanation of the band name in 1998, stating: "It refers to two friends, Jacqueline and Olivia, who were separated during the California earthquake of 1906 and have been searching for each other ever since, across different dimensions of time and space."[8]

- ^ Playing Dusk at Cubist Castle and Explanation II in synchronicity does not produce quadraphonic sound, as the two albums are of different lengths.[11]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Cooper 2005, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Cooper 2005, p. 9.

- ^ Clair 2022, Chapter 7 (Search phrase "Years earlier, listening to Pylon together on a drive out to a water park in Shreveport, Will, Jeff, and Robert decided they'd live in Athens together someday").

- ^ Cooper 2005, p. 18.

- ^ Clair 2022, Chapter 7 (Search phrase "Synthetic Flying Machine didn’t last very long").

- ^ Clair 2022, Chapter 7 (Search phrase "Will and Bill felt like a name change was in order").

- ^ Kramer n.d., p. 3.

- ^ Holmes 1998, p. 03.

- ^ a b Clair 2022, Chapter 10 (Search phrase "Meanwhile, Bill found himself losing interest in playing with Chocolate USA").

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Clair 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Houle 2011.

- ^ a b c Umile 2004.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Thompson 2011.

- ^ a b c Ankeny n.d.

- ^ Clair 2022, Chapter 10 (Search phrase "The full name of the album, Music from the Unrealized Film Script: Dusk at Cubist Castle, suggests it's the score to an abandoned movie project").

- ^ Scapelliti 2022.

- ^ Clair 2022, Chapter 10 (Search phrase " It's supposed to be dream music for your mind").

- ^ Vaziri 1997.

- ^ a b Anon. 1996, p. 97.

- ^ a b Cohen 1996.

- ^ LeMay 2011.

- ^ a b Cox 1996, p. 50.

- ^ a b Black 1996, p. 140.

- ^ a b Sarig 2004, p. 603.

- ^ a b Stephens 1996, p. 155.

- ^ a b Gretel n.d.

- ^ Anon. 2021.

- ^ a b Anon. n.d.

- ^ Buckley 2003, p. 749.

- ^ Clair 2022, Chapter 14 (Search phrase "But that fall, not long after Dusk was released, the band needed a keyboard player").

- ^ Anon. 1997.

- ^ Anon. 2003.

References

[edit]- Ankeny, Jason (n.d.). "Music from the Unrealized Film Script, Dusk at Cubist Castle – The Olivia Tremor Control". AllMusic. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- Anon. (n.d.). "Discography". The Olivia Tremor Control. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- Anon. (October 1996). "The Olivia Tremor Control: Music from the Unrealized Film Script: Dusk at Cubist Castle". Alternative Press. No. 99.

- Anon. (February 25, 1997). "The 1996 Pazz & Jop Critics Poll". The Village Voice. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- Anon. (November 16, 2003). "Top 100 Albums of the 1990s". Pitchfork. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- Anon. (August 6, 2021). "The Olivia Tremor Control Released Debut Album 'Music From The Unrealized Script: Dusk At Cubist Castle' 25 Years Ago Today". Magnet. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

- Black, Johnny (December 1996). "The Olivia Tremor Control: Music from the Unrealized Film Script: Dusk at Cubist Castle". Q. No. 123.

- Buckley, Jonathan (2003). The Rough Guide to Rock. Rough Guides. ISBN 1-85828-457-0.

- Clair, Adam (September 21, 2016). "Elephant 6 & Friends Reflect On The Legacy Of The Olivia Tremor Control's Dusk At Cubist Castle". Stereogum. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- Clair, Adam (2022). Endless Endless, A Lo-Fi History of the Elephant 6 Mystery (E-book). Hachette. ISBN 978-0-30692-3968.

- Cohen, Jason (November 15, 1996). "Olivia Tremor Control: Music From the Unrealized Film Script Dusk at Cubist Castle (Flydaddy)". The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- Cooper, Kim (2005). In the Aeroplane Over the Sea. 33⅓. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8264-1690-X.

- Cox, Tom (September 21, 1996). "The Olivia Tremor Control – Music From The Unrealized Film Script: Dusk At Cubist Castle". NME. Archived from the original on September 30, 2000. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- Gretel (n.d.). "Music from the Unrealized Film Script, Dusk at Cubist Castle". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on August 18, 2004. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

- Holmes, Catherine Mantione (March 27, 1998). "Pop Music Tremor Control shakes things up". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- Houle, Zachary (November 8, 2011). "The Olivia Tremor Control Reissues 'Dusk at Cubist Castle' and 'Black Foliage'". PopMatters. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- Kramer, Michael (n.d.). "Homemade Psychedelia For Modern Times". The New York Times. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- LeMay, Matt (November 15, 2011). "The Olivia Tremor Control: Music From The Unrealized Film Script, Dusk At Cubist Castle / Black Foliage: Animation Music, Vol. 1". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on September 17, 2023. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- Sarig, Roni (2004). "Olivia Tremor Control". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Scapelliti, Christopher (November 10, 2022). "Watch Indie-Rock Legends the Olivia Tremor Control Perform Their Infectious Signature Song, 'Jumping Fences'". Guitar Player. Retrieved July 31, 2023.

- Stephens, Chuck (September 1996). "Olivia Tremor Control: Music from the Unrealized Film Script—'Dusk at Cubist Castle'". Spin. Vol. 12, no. 6.

- Thompson, Paul (November 17, 2011). "The Olivia Tremor Control: Music From the Unrealized Film Script: Dusk at Cubist Castle / Black Foliage: Animation Music Vol. 1". Pitchfork. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- Umile, Dominic (March 8, 2004). "The Olivia Tremor Control: Music From The Unrealized Film Script, Dusk At Cubist Castle [Reissue]". PopMatters. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- Vaziri, Aidin (January 26, 1997). "Olivia Tremor Control Shakes Up The System". San Francisco Examiner.