John S. Marmaduke

John S. Marmaduke | |

|---|---|

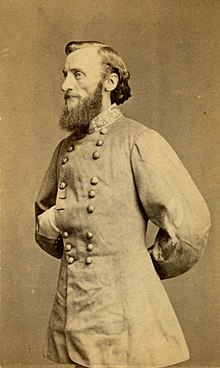

Major-General John S. Marmaduke, portrait carte de visite by Charles D. Fredricks | |

| 25th Governor of Missouri | |

| In office January 12, 1885 – December 28, 1887 | |

| Lieutenant | Albert P. Morehouse |

| Preceded by | Thomas T. Crittenden |

| Succeeded by | Albert P. Morehouse |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Sappington Marmaduke March 14, 1833 Saline County, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | December 28, 1887 (aged 54) Jefferson City, Missouri, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Pneumonia |

| Resting place | Woodland Cemetery, Jefferson City, Missouri, U.S. 38°34′02.7″N 92°09′43.6″W / 38.567417°N 92.162111°W |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Parent |

|

| Education | Yale College Harvard University United States Military Academy |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Branch/service |

|

| Years of service |

|

| Rank |

|

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars |

|

John Sappington Marmaduke (March 14, 1833 – December 28, 1887) was an American politician and soldier. He was the 25th governor of Missouri from 1885 until his death in 1887. During the American Civil War, he was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army who commanded cavalry in the Trans-Mississippi Theater.

On September 6, 1863, Marmaduke killed a Confederate brigadier general, Lucius M. Walker, in a duel. Confederate Major General Sterling Price ordered Marmaduke's arrest but suspended the order because of the impending U.S. advance on Little Rock, Arkansas. Marmaduke never faced a court martial for the duel.

Early life and education

[edit]

Marmaduke was born on March 14, 1833, in Saline County, Missouri, the second son of ten children born to Lavinia (née Sappington)[1] and Meredith Miles Marmaduke (1791–1864). His father was the 8th governor of Missouri, succeeding to the office after the suicide of his predecessor. A successful planter, he held numerous enslaved African Americans as workers on the plantation.[2] The family was quite political, and Marmaduke's great-grandfather, John Breathitt, had been the governor of Kentucky from 1832 to 1834, dying in office.[3]

Marmaduke attended Chapel Hill Academy in Lafayette County, Missouri, and Masonic College in Lexington, Missouri, before attending Yale University for two years and then Harvard University for another year.[3] U.S. Representative John S. Phelps appointed Marmaduke to the United States Military Academy, from which he graduated in 1857, placing 30th out of 38 students.[4] He was a second lieutenant in the 1st United States Mounted Riflemen, before being transferred to the 2nd United States Cavalry under Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston. Marmaduke later served in the Utah War and was posted to Camp Floyd, Utah, in 1858–1860.[4]

American Civil War

[edit]

Marmaduke was on duty in the New Mexico Territory in the spring of 1861 when he received news that several southern states had declared secession from the United States (Union). He returned home to Missouri to meet with his father, a strong Unionist. Afterward, Marmaduke resigned from the United States Army, effective April 1861. Pro-secession Missouri Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson, Marmaduke's uncle, soon appointed him as the colonel of the 1st Regiment of Rifles, a unit from Saline County, Missouri, in the Missouri State Guard.[4]

Governor Jackson left Jefferson City, Missouri, in June, along with State Guard commander Major-General Sterling Price, to recruit more troops. Marmaduke and his regiment met them at Boonville, Missouri. Within a short time, Price and Jackson left, leaving Marmaduke in charge of a small force of militia. Marmaduke's troops were not adequately prepared for combat, but Governor Jackson ordered him to stand against U.S. forces who had entered the state. U.S. brigadier-general Nathaniel Lyon's 1,700 well-trained and equipped soldiers easily routed Marmaduke's untrained and poorly armed force at the Battle of Boonville on June 17, 1861. The skirmish was mockingly dubbed "the Boonville Races" by Unionists because Marmaduke's forces broke and ran after 20 minutes of battle.[3]

Disgusted by the situation, Marmaduke resigned his commission in the Missouri State Guard and traveled to Richmond, Virginia, where he was commissioned a first lieutenant in the regular Confederate States Army.[3] The Confederate States War Department ordered him to report for duty in Arkansas, where he soon was elected lieutenant-colonel of the 1st Arkansas Battalion.[4] He was on the staff of Lieutenant-General William J. Hardee, a former United States Military Academy instructor of infantry tactics. Marmaduke's former Utah War commander, Albert Sidney Johnston, asked him to join his staff in early 1862.[5] Marmaduke was wounded in action at the Battle of Shiloh as colonel of the 3rd Confederate Regiment, incapacitating him for several months.[6]

In November 1862, the C.S. War Department confirmed Marmaduke's promotion to brigadier-general. His first battle as a brigade commander was at the Battle of Prairie Grove.[7] In April 1863, he left Arkansas with 5,000 men and ten artillery pieces and entered U.S.-held Missouri. However, he was repulsed at the Battle of Cape Girardeau and forced to return to Helena, Arkansas.[8] Controversy soon followed. In September 1863, he accused his immediate superior officer, Brigadier-General Lucius M. Walker, of cowardice in action for not being present with his men on the battlefield. Walker, slighted by the insult, challenged Marmaduke to a duel, which resulted in Walker's death on September 6, 1863.[8]

Marmaduke later commanded a cavalry division in the Trans-Mississippi Department, participating in the Red River Campaign. While commanding a mixed force of Confederate troops, including Native-American soldiers of the 1st, and 2nd Choctaw Regiments, he defeated a U.S. foraging detachment at the Battle of Poison Spring, Arkansas, on April 18, 1864. He was hailed in the Confederate press for what was publicized as a significant Confederate victory.

Marmaduke commanded a division in Major-General Sterling Price's Raid in September–October 1864 into Missouri, where Marmaduke was captured at the Battle of Mine Creek in Kansas (by Private James Dunlavy of the 3rd Iowa Cavalry).[8] While still a prisoner of war at Johnson's Island in Ohio, Marmaduke was promoted to major-general in March 1865. He was released after the war ended.[7] His younger brother, Henry Hungerford Marmaduke, who was in the Confederate States Navy, was captured and imprisoned on Johnson's Island. He later served the U.S. government in negotiations with South American nations. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Two other Marmaduke brothers died in the American Civil War.[9]

Later life and death

[edit]Marmaduke returned home to Missouri and settled in Carondelet, St. Louis. He worked briefly for an insurance company, whose ethics he found contrary to his own. He then edited an agricultural journal and publicly accused the railroads of discriminatory pricing against local farmers. The governor soon appointed Marmaduke to the state's first Rail Commission.[9] Marmaduke decided to enter politics but lost the 1880 Democratic nomination for governor to the former U.S. general Thomas Theodore Crittenden, who had strong support and financial backing from the railroads. Undeterred, he ran again for governor four years later, when public opinion had changed, and railroad reform and regulation became more in vogue. Marmaduke conducted a campaign that highlighted his Confederate service, emphasized abuses of Missourians by U.S. soldiers during the Civil War, celebrated the activities of pro-Confederate "partisan guerrillas" such as William Clarke Quantrill, and claimed that the Republican Party in Missouri was a tool of "carpetbaggers" to oppress "native" Missourians. He was elected on a platform officially focused on cooperation between former Unionists and Confederates, promising an agenda to produce a "New Missouri". He settled potentially crippling railroad strikes in 1885 and 1886. The following year, Marmaduke pushed laws through the state legislature that finally began regulating the state's railway industry. He also dramatically boosted the state's funding of public schools, with nearly a third of the annual budget allocated to education.

Marmaduke never married, and his two nieces were hostesses at the governor's mansion.[10] Like his great-grandfather, he died while governor. He contracted pneumonia late in 1887 and died in Jefferson City, Missouri, where he was buried in Woodland Cemetery.[10]

Legacy

[edit]Marmaduke, Arkansas, is named after him.[11]

See also

[edit]- Cavalry in the American Civil War

- List of American Civil War generals

- List of United States Military Academy alumni

- List of governors of Missouri

- List of pneumonia victims

Notes

[edit]- ^ Shoemaker's pp. 189–190

- ^ Christensen, Lawrence O., Dictionary of Missouri Biography, University of Missouri Press, 1999.

- ^ a b c d Parrish's, pp. 16–17

- ^ a b c d Welsh's p. 154

- ^ Johnston's pp. 583–584

- ^ Neal's pp. 142–143

- ^ a b Black's pp. 159

- ^ a b c Conard's pp. 199–200

- ^ a b Reavis's pp. 510–511

- ^ a b McClure pp. 175–176

- ^ Houston's pp. 10

References

[edit]- Black, William P., Banasik, Michael E., Victoria, and Albert Museum, Duty, Honor, and Country: The Civil War Experiences of Captain William P. Black, Thirty-Seventh Illinois Infantry, Press of the Camp Pope Bookshop, 2006. ISBN 1-929919-10-7.

- Conrad, Howard Louis, Encyclopedia of the History of Missouri: A Compendium of History and Biography for Ready Reference, Published by The Southern History Company, Haldeman, Conard & Co., Proprietors, 1901.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Hinze, David; Farnham, Karen, The Battle of Carthage, Border War in Southwest Missouri, July 5, 1861. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-58980-223-3.

- Houston, Curtis A., The Houston Family and Relatives, C.A. Houston, 1984.

- Johnston, William Preston, Johnston, Albert Sidney, The life of Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston: embracing his services in the armies of the United States, the republic of Texas, and the Confederate States, D. Appleton, 1878.

- McClure, Clarence Henry, History of Missouri: A Text Book of State History for Use in Elementary Schools, A.S. Barnes Company, 1920.

- Neal, Diane, Kremm, Thomas, The Lion of the South: General Thomas C. Hindman, Mercer University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-86554-556-1.

- Parrish, William Earl, McCandless, Perry, Foley, William E., A History of Missouri, University of Missouri Press, 1971. ISBN 0-8262-1559-9.

- Ponder, Jerry, Major-General John S. Marmaduke, C.S.A., Doniphan, Missouri: Ponder Books, 1999. ISBN 0-9623922-8-6.

- Reavis, L. U., Saint Louis: the Future Great City of the World, Gray, Baker & Co., 1875.

- Shoemaker, Floyd C., A History of Missouri and Missourians: A Text Book for "class A" Elementary Grade, Freshman High School, and Junior High School, Ridgway, 1922.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

- Welsh, Jack D., Medical Histories of Confederate Generals, Kent State University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-87338-649-3.

External links

[edit]- John S. Marmaduke at Find a Grave

- John S. Marmaduke at the National Governors Association

- John S. Marmaduke at The Political Graveyard

- Marmaduke-Walker Duel at Encyclopedia of Arkansas

- Marmaduke-Walker Duel at Historical Marker Database

- Sappington-Marmaduke Family Papers at the Missouri Historical Society

- 1833 births

- 1887 deaths

- 19th-century Missouri politicians

- American Civil War prisoners of war

- American duellists

- Cavalry commanders

- Confederate States Army major generals

- Deaths from pneumonia in Missouri

- Democratic Party governors of Missouri

- Harvard College alumni

- Missouri State Guard

- People from Saline County, Missouri

- People of Missouri in the American Civil War

- Southern Historical Society

- United States Military Academy alumni

- Yale College alumni