Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán

Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán | |

|---|---|

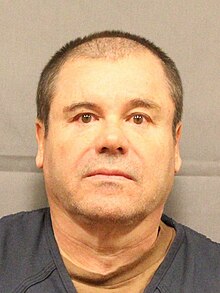

Booking photo from January 2017 | |

| Born | Joaquín Archivaldo Guzmán Loera 4 April 1957 |

| Other names |

|

| Occupation | Leader of Sinaloa Cartel |

| Height | 168 cm (5 ft 6 in) |

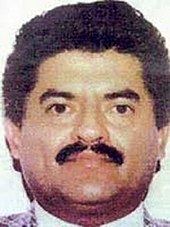

| Predecessor | Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo |

| Successor | Ismael Zambada García |

| Criminal status | Incarcerated |

| Spouses | At least 4

|

| Children | At least 15

|

| Parents |

|

| Conviction(s) |

|

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment without the possibility of parole plus 30 years, must forfeit assets worth more than $12.6 billion.[1] |

Reward amount | Mexico: US$3.8 million[2] United States: US$5 million[3] |

Capture status |

|

Wanted by | Attorney General of Mexico, the Drug Enforcement Administration, and numerous sub-national entities. |

| Escaped |

|

| Imprisoned at | ADX Florence near Florence, Colorado, US[4] |

| Signature | |

Joaquín Archivaldo Guzmán Loera (Spanish: [xoaˈkin aɾtʃiˈβaldo ɣusˈman loˈeɾa]; born 4 April 1957), commonly known as "El Chapo", is a Mexican former drug lord and a former leader within the Sinaloa Cartel. Guzmán is believed to be responsible for the deaths of over 34,000 people,[5] and was considered to be the most powerful drug trafficker in the world until he was extradited to the United States and sentenced to life in prison.[6][7]

Guzmán was born in Sinaloa and raised in a poor farming family. He endured much physical abuse at the hands of his father, through whom he also entered the drug trade, helping him grow marijuana for local dealers during his early adulthood. Guzmán began working with Héctor Luis Palma Salazar by the late 1970s, one of the nation's rising drug lords. He helped Salazar map routes to move drugs through Sinaloa and into the United States. He later supervised logistics for Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo, one of the nation's leading kingpins in the mid 1980s, but Guzmán founded his own cartel in 1988 after Félix's arrest.

Guzmán oversaw operations whereby mass cocaine, methamphetamine, marijuana,[8] and heroin were produced, smuggled into, and distributed throughout the United States and Europe, the world's largest users.[9][10] He achieved this by pioneering the use of distribution cells and long-range tunnels near borders,[3] which enabled him to export more drugs to the United States than any other trafficker in history.[11] Guzmán's leadership of the cartel also brought immense wealth and power; Forbes ranked him as one of the most powerful people in the world between 2009 and 2013,[12] while the Drug Enforcement Administration estimated that he matched the influence and wealth of Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar.[13]

Guzmán was first captured in 1993 in Guatemala and then was extradited and sentenced to 20 years in prison in Mexico for murder and drug trafficking.[3][14] He bribed multiple prison guards and escaped from a federal maximum-security prison in 2001.[3] His status as a fugitive resulted in an $8.8 million combined reward from Mexico and the U.S. for information leading to his capture,[3] and he was arrested in Mexico in 2014.[11][15] He escaped prior to formal sentencing in 2015, through a tunnel dug by associates into his jail cell.[16] Mexican authorities recaptured him following a shoot-out in January 2016,[17] and extradited him to the U.S. a year later. In 2019, he was found guilty of a number of criminal charges related to his leadership of the Sinaloa Cartel,[18] was sentenced to life imprisonment, and incarcerated in ADX Florence, Colorado, United States.[19][20]

Early life

Joaquín Archivaldo Guzmán Loera was born on 4 April 1957 into a poor family in the rural community of La Tuna, Badiraguato, Sinaloa, Mexico.[21][22][a][25] His parents were Emilio Guzmán Bustillos and María Consuelo Loera Pérez.[26] His paternal grandparents were Juan Guzmán and Otilia Bustillos, and his maternal grandparents were Ovidio Loera Cobret and Pomposa Pérez Uriarte. For many generations, his family lived at La Tuna.[27] His father was officially a cattle rancher, as were most in the area where he grew up; according to some sources, however, he might also have been a gomero, an opium poppy farmer.[28] He has two younger sisters named Armida and Bernarda and four younger brothers named Miguel Ángel, Aureliano, Arturo, and Emilio. He had three unnamed older brothers who reportedly died of natural causes when he was very young.[27]

Few details are known about Guzmán's upbringing. As a child, he sold oranges and dropped out of school in third grade to work with his father and as a result is functionally illiterate.[14][29] He was known for being a practical joker and enjoyed playing pranks on his friends and family when he was young.[30] He was regularly beaten, and he sometimes fled to his maternal grandmother's house to escape such treatment. However, he stood up to his father to protect his younger siblings from being beaten.[31][32] It is possible that Guzmán incurred his father's wrath for trying to stop him from beating them. His mother was his "foundation of emotional support".[33] The nearest school to his home was about 100 km (60 mi) away, and he was taught by traveling teachers during his early years. The teachers stayed for a few months before moving to other areas.[32] With few opportunities for employment in his hometown, he turned to the cultivation of opium poppy, a common practice among local residents.[34] During harvest season, Guzmán and his brothers hiked the hills of Badiraguato to cut the bud of the poppy. Once the plant was stacked in kilos, his father sold the harvest to other suppliers in Culiacán and Guamúchil.[35] He sold marijuana at commercial centers near the area while accompanied by Guzmán. His father spent most of the profits on liquor and women and often returned home with no money. Tired of his mismanagement, Guzmán cultivated his own marijuana plantation at age 15 with cousins Arturo, Alfredo, Carlos, and Héctor Beltrán Leyva, and he supported his family with his marijuana production.[31]

When he was a teenager, his father kicked him out of the house, and he went to live with his grandfather.[36] It was during his adolescence that Guzmán gained the nickname "El Chapo", Mexican slang for "shorty", for his 1.68-metre (5 ft 6 in) stature and stocky physique.[37][38] Most people in Badiraguato worked in the poppy fields of the Sierra Madre Occidental for most of their lives, but Guzmán left his hometown in search of greater opportunities through his uncle Pedro Avilés Pérez, one of the pioneers of Mexican drug trafficking. He left Badiraguato in his twenties and joined organized crime.[39]

Early career

During the 1980s, the leading crime syndicate in Mexico was the Guadalajara Cartel,[40] which was headed by Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo (alias "El Padrino" or "The Godfather"), Rafael Caro Quintero, Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo (alias "Don Neto"), Juan José Esparragoza Moreno (alias El Azul, "The Blue One") and others.[41] In the 1970s, Guzmán first worked for the drug lord Héctor "El Güero" Palma by transporting drugs and overseeing their shipments from the Sierra Madre region to urban areas near the Mexico–U.S. border by aircraft. Since his initial steps in organized crime, Guzmán was ambitious and regularly pressed on his superiors to allow him to increase the share of narcotics that were smuggled across the border. He also favored a violent and serious approach when doing business; if any of his drug shipments were not on time, Guzmán would simply kill the smuggler himself by shooting him in the head. Those around him learned that cheating him or going with other competitors—even if they offered better prices—was unwise.[citation needed] The leaders of the Guadalajara Cartel liked Guzmán's business acumen, and in the early 1980s introduced him to Félix Gallardo, one of the major drug lords in Mexico at that time.[42] Guzmán worked as a chauffeur for Félix Gallardo, before being put in charge of logistics,[43] where Guzmán coordinated drug shipments from Colombia to Mexico by land, air, and sea. Palma ensured the deliveries arrived in the United States. Guzmán earned enough standing and began working for Félix Gallardo directly.[42]

Throughout most of the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Mexican drug traffickers were also middlemen for the Colombian trafficking groups, and transported cocaine across the Mexico–U.S. border. Mexico, however, remained a secondary route for the Colombians, given that most of the drugs trafficked by their cartels were smuggled through the Caribbean and the Florida corridor.[44][45] Félix Gallardo was the leading drug baron in Mexico and friend of Juan Ramón Matta-Ballesteros, but his operations were still limited by his counterparts in South America. In the mid-1980s, however, the U.S. government increased law enforcement surveillance and put pressure on the Medellín and Cali cartels by effectively reducing the drug trafficking operations in the Caribbean corridor. Realizing it was more profitable to hand over the operations to their Mexican counterparts, the Colombian cartels gave Félix Gallardo more control over their drug shipments.[46][47] This power shift gave the Mexican organized crime groups more leverage over their Central American and South American counterparts.[44] During the 1980s, however, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was conducting undercover groundwork in Mexico, where several of its agents worked as informants.

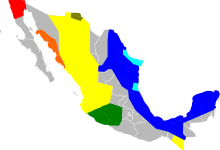

One DEA agent, Enrique Camarena Salazar, was working as an informant and grew close to many top drug barons, including Félix Gallardo.[48] In November 1984, the Mexican military—acting on the intelligence information provided by Camarena—raided a large marijuana plantation owned by the Guadalajara Cartel and known as "Rancho Búfalo".[49] Angered by the suspected betrayal, Félix Gallardo and his men exacted revenge when they kidnapped, tortured, and killed Camarena in February 1985.[50] The death of Camarena outraged Washington, and Mexico responded by carrying out a massive manhunt to arrest those involved in the incident.[51] Guzmán took advantage of the internal crisis to gain ground within the cartel and take over more drug trafficking operations.[31] In 1989, Félix Gallardo was arrested; while in prison and through a number of envoys, the drug lord called for a summit in Acapulco, Guerrero. In the conclave, Guzmán and others discussed the future of Mexico's drug trafficking and agreed to divide the territories previously owned by the Guadalajara Cartel.[citation needed] The Arellano Félix brothers formed the Tijuana Cartel, which controlled the Tijuana corridor and parts of Baja California; in Chihuahua state, a group controlled by Carrillo Fuentes family formed the Juárez Cartel; and the remaining faction left to Sinaloa and the Pacific Coast and formed the Sinaloa Cartel under the traffickers Ismael "El Mayo" Zambada, Palma, and Guzmán.[52][40] Guzmán was specifically in charge of the drug corridors of Tecate, Baja California,[52] and Mexicali and San Luis Río Colorado, two border crossings that connect the states of Sonora and Baja California with the U.S. states of Arizona and California.[53]

When Félix Gallardo was arrested, Guzmán reportedly lived in Guadalajara, Jalisco for some time. One of his other centers of operation, however, was in the border city of Agua Prieta, Sonora, where he coordinated drug trafficking activities more closely. Guzmán had dozens of properties in various parts of the country. People he trusted purchased the properties for him and registered them under false names. Most of them were located in residential neighborhoods and served as stash houses for drugs, weapons, and cash. Guzmán also owned several ranches across Mexico, but most of them were located in the states of Sinaloa, Durango, Chihuahua, and Sonora, where locals working for the drug lord grew opium and marijuana.[54] The first time Guzmán was detected by U.S. authorities for his involvement in organized crime was in 1987, when several protected witnesses testified in a U.S. court that Guzmán was in fact heading the Sinaloa Cartel. An indictment issued in the state of Arizona alleged that Guzmán had coordinated the shipment of 2,000 kg (4,400 lb) of marijuana and about 4,700 kg (10,400 lb) of cocaine from 19 October 1987 to 18 May 1990, and had received roughly US$1.5 million in drug proceeds that were shipped back to his home state. Another indictment alleged that Guzmán earned US$100,000 for trafficking 32,000 kg (70,000 lb) of cocaine and an unspecified amount of marijuana in a period of three years.[55] In the border areas between Tecate and San Luis Río Colorado, Guzmán ordered his men to traffic most of the drugs overland, but also through a few aircraft. By using the so-called piecemeal strategy, in which traffickers kept drug quantities relatively low, risks were reduced. Guzmán also pioneered the use of sophisticated tunnels to move drugs across the border and into the United States.[56] Aside from pioneering the tunnels, Palma and Guzmán packed cocaine into chili pepper cans under the brand "La Comadre" before they were shipped to the U.S. by train.[57] In return, the drug lords were paid through large suitcases filled with millions of dollars in cash. These suitcases were flown from the U.S. to Mexico City, where corrupt customs agents at the airport made sure the deliveries were not inspected. Large sums of that money were reportedly used as bribes for members of the Attorney General's Office.[14]

Tijuana Cartel conflict: 1989–1993

When Félix Gallardo was arrested, the Tijuana corridor was handed over to the Arellano Félix brothers, Jesús Labra Áviles (alias "El Chuy"), and Javier Caro Payán (alias "El Doctor"), cousin of the former Guadalajara Cartel leader Rafael Caro Quintero. In fears of a coup, however, Caro Payán fled to Canada and was later arrested. Guzmán and the rest of the Sinaloa Cartel leaders consequently grew angry at the Arellano Félix clan about this.[58] In 1989, Guzmán sent Armando López (alias "El Rayo"), one of his most trusted men, to speak with the Arellano Félix clan in Tijuana. Before he had a chance to speak face-to-face with them, López was killed by Ramón Arellano Félix. The corpse was disposed of in the outskirts of the city and the Tijuana Cartel ordered a hit on the remaining members of the López family to prevent future reprisals.[59][60] That same year, the Arellano Félix brothers sent the Venezuelan drug trafficker Enrique Rafael Clavel Moreno to infiltrate Palma's family and seduce his wife Guadalupe Leija Serrano.[61] After convincing her to withdraw US$7 million from one of Palma's bank accounts in San Diego, California, Clavel beheaded her and sent her head to Palma in a box.[62] It was known as the first beheading linked to the drug trade in Mexico.[63] Two weeks later, Clavel killed Palma's children, Héctor (aged 5) and Nataly (aged 4), by throwing them off a bridge in Venezuela. Palma retaliated by sending his men to kill Clavel while he was in prison.[64] In 1991, Ramón killed another Sinaloa Cartel associate, Rigoberto Campos Salcido (alias "El Rigo"), and prompted bigger conflicts with Guzmán.[59][60] In early 1992, a Tijuana Cartel-affiliated and San Diego-based gang known as Calle Treinta kidnapped six of Guzmán's men in Tijuana, tortured them to obtain information, and then shot them in the back of their heads. Their bodies were dumped on the outskirts of the city. Shortly after the attack, a car bomb exploded outside one of Guzmán's properties in Culiacán. No injuries were reported, but the drug lord became fully aware of the intended message.[65]

Guzmán and Palma struck back against the Arellano Félix brothers (Tijuana Cartel) with nine killings on 3 September 1992 in Iguala;[14][66] among the dead were lawyers and family members of Félix Gallardo, who was also believed to have orchestrated the attack against Palma's family.[67] Mexico's Attorney General formed a special unit to look into the killings, but the investigation was called off after the unit found that Guzmán had paid off some of the top police officials in Mexico with $10 million, according to police reports and confessions of former police officers.[14] In November 1992, gunmen of Arellano Félix attempted to kill Guzmán as he was traveling in a vehicle through the streets of Guadalajara. Ramón and at least four of his henchmen shot at the moving vehicle with AK-47 rifles, but the drug lord managed to escape unharmed. The attack forced Guzmán to leave Guadalajara and live under a false name under fears of future attacks.[14][31] He and Palma, however, responded to the assassination attempt in a similar fashion; several days later, on 8 November 1992, a large number of Sinaloa Cartel men posing as policemen stormed the Christine discothèque in Puerto Vallarta, spotted Ramón, Francisco Javier Arellano Félix, David Barron Corona, and opened fire at them. The shooting lasted for at least eight minutes, and more than 1,000 rounds were fired by both Guzmán's and Arellano Félix's gunmen.[68] Six people were killed in the shootout, but the Arellano Félix brothers were in the restroom when the raid started and reportedly escaped through an air-conditioning duct before leaving the scene in one of their vehicles.[69][70] On 9 and 10 December 1992, four alleged associates of Félix Gallardo were killed. The antagonism between Guzmán's Sinaloa Cartel and the Arellano Félix clan left several more dead and was accompanied by more violent events in the states of Baja California, Sonora, Sinaloa, Durango, Jalisco, Guerrero, Michoacán and Oaxaca.[71]

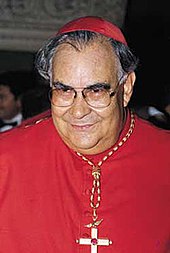

The war between both groups continued for six more months, yet none of their respective leaders were killed. In mid-1993, the Arellano Félix clan sent their top gunmen on a final mission to kill Guzmán in Guadalajara, where he moved around frequently to avoid any possible attacks. Having no success, the Tijuana Cartel hitmen decided to return to Baja California on 24 May 1993. As Francisco Javier was at the Guadalajara International Airport booking his flight to Tijuana, informant tips notified him that Guzmán was at the airport parking lot awaiting a flight to Puerto Vallarta.[72] Having spotted the white Mercury Grand Marquis car where Guzmán was thought to be hiding, about 20 gunmen of the Tijuana Cartel descended from their vehicles and opened fire at around 4:10 p.m. However, the drug lord was inside a green Buick sedan a short distance from the target. Inside the Mercury Grand Marquis was the cardinal and archbishop of Guadalajara Juan Jesús Posadas Ocampo, who died at the scene from fourteen gunshot wounds.[73] Six other people, including the cardinal's chauffeur, were caught in the crossfire and killed.[74][75] Amidst the shootout and confusion, Guzmán escaped and headed to one of his safe houses in Bugambilias, a neighborhood 20 minutes away from the airport.[72][76]

Flight and first arrest 1993

The night the cardinal was killed, Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari flew to Guadalajara and condemned the attack, stating it was "a criminal act" that targeted innocent civilians, but he did not give any indications of the involvement of organized crime.[73] The death of Cardinal Posadas Ocampo, a high-profile religious figure, outraged the Mexican public, the Catholic Church, and many politicians. The government responded by carrying out a massive manhunt to arrest the people involved in the shootout, and offered about US$5 million bounties for each of them.[77] Pictures of Guzmán's face, previously unknown to the public, started to appear in newspapers and television across Mexico. Fearing his capture, Guzmán fled to Tonalá, Jalisco, where he reportedly owned a ranch. The drug lord then fled to Mexico City and stayed at a hotel for about ten days.[76] He met with one of his associates in an unknown location and handed him US$200 million to provide for his family in case of his absence. He gave that same amount to another of his employees to make sure the Sinaloa Cartel ran its day-to-day activities smoothly in case he was gone for some time.[77]

After obtaining a passport with the fake name of Jorge Ramos Pérez, Guzmán was transported to the southern state of Chiapas by one of his trusted associates before leaving the country and settling in Guatemala on 4 June 1993.[77] His plan was to move across Guatemala with his girlfriend María del Rocío del Villar Becerra and several of his bodyguards and settle in El Salvador.[76] During his travel, Mexican and Guatemalan authorities were tracking his movements. Guzmán paid a Guatemalan military official US$1.2 million to allow him to hide south of the Mexican border. The unnamed official, however, passed information about Guzmán's whereabouts to law enforcement.[78][79] On 9 June 1993, Guzmán was arrested by the Guatemalan Army at a hotel near Tapachula, close to the Guatemala–Mexico border.[80][81] He was extradited to Mexico two days later aboard a military airplane,[76][82][83] where he was immediately taken to the Federal Social Readaptation Center No. 1 (often referred to simply as "La Palma" or "Altiplano"), a maximum-security prison in Almoloya de Juárez, State of Mexico.[84][14] He was sentenced to 20 years, nine months in prison on charges of drug trafficking, criminal association and bribery. Initially jailed at Federal Social Readaptation Center No. 1, on 22 November 1995, he was transferred to another maximum security prison, Federal Center for Social Rehabilitation No. 2 (also known as "Puente Grande") in Jalisco, after being convicted of three crimes: possession of firearms, drug trafficking and the murder of Cardinal Ocampo (the charge would later be dismissed by another judge). He had been tried and sentenced inside the federal prison on the outskirts of Almoloya de Juárez, Mexico State.[85]

While he was in prison, Guzmán's drug empire and cartel continued to operate unabated, run by his brother, Arturo Guzmán Loera, known as El Pollo, with Guzmán himself still considered a major international drug trafficker by Mexico and the U.S. even while he was behind bars.[86] Associates brought him suitcases of cash to bribe prison workers and allow the drug lord to maintain his opulent lifestyle even in prison, with prison guards acting like his servants.[87][88] He met his longtime mistress and later Sinaloa associate, former police officer Zulema Hernández, while in prison, where she was serving time for armed robbery.[89] Hernández later controlled Sinaloa's expansion into Mexico City, but in 2008 her body was found in a trunk, carved with multiple Zs, signifying Los Zetas, Sinaloa's archrivals.[89]

Drug empire

Guzmán's Sinaloa Cartel, at the time of his arrest, was the wealthiest and most powerful of Mexico's drug cartels. It smuggled multi-ton cocaine shipments from Colombia through Mexico to the United States by air, sea and road, and had distribution cells throughout the U.S.[3][11] The organization has also been involved in the production, smuggling and distribution of Mexican methamphetamine, marijuana, and heroin from Southeast Asia.[86]

When Palma was arrested by the Mexican Army on 23 June 1995, Guzmán took leadership of the cartel.[90][91] Palma was later extradited to the United States, where he is in prison on charges of drug trafficking and conspiracy.[14]

After Guzmán's prison escape nearly a decade after his initial arrest, he and close associate Ismael Zambada García became Mexico's undisputed top drug kingpins after the 2003 arrest of their rival Osiel Cárdenas of the Gulf Cartel. Until Guzmán's arrest in 2014, he was considered the "most powerful drug trafficker in the world" by the U.S. Department of the Treasury.[7][92] Guzmán also had another close associate, his trusted friend Ignacio "Nacho" Coronel Villarreal.[93][94]

A U.S. indictment states that from 2012, Guzmán and the Sinaloa Cartel bribed Juan Orlando Hernández with millions of dollars that helped him become President of Honduras in 2013. This influence helped the Cartel and its allies control and protect vital maritime and air transshipment destinations between the United States and South America.[95]

His drug empire made Guzmán a billionaire, and he was ranked the 10th richest man in Mexico and 1,140th in the world in 2011, with a net worth of roughly US$1 billion.[96] To assist his drug trafficking, the Sinaloa Cartel also built a shipping and transport empire.[11] Guzmán has been referred to as the "biggest drug lord of all time",[97] and the U.S. DEA considered him "the godfather of the drug world" and strongly estimates he surpassed the influence and reach of Pablo Escobar. In 2013, the Chicago Crime Commission named Guzmán "Public Enemy Number One" for the influence of his criminal network in Chicago (however, there is no evidence Guzmán has ever visited the city). The last person to receive such notoriety was Al Capone in 1930.

At the time of his 2014 arrest, Guzmán imported more drugs into the United States than anyone else.[11] He took advantage of the power vacuum created by crackdowns on cartels in Colombia, gaining business and market share there as Colombia's own cartels were decimated.[98] He took similar advantage of the situation when his rival cartels were brought down by an intense crackdown from the Mexican government, but the Sinaloa gang emerged largely unscathed.[99]

Methamphetamine production

After the fall of the Amezcua brothers – founders of the Colima Cartel – in 1999 on methamphetamine trafficking charges, there was a demand for leadership throughout Mexico to coordinate methamphetamine shipments north. Guzmán saw an opportunity and seized it.[85] Easily arranging precursor shipments, Guzmán and Ismael Zambada García ("El Mayo") made use of their previous contacts on Mexico's Pacific coast. Importantly, for the first time, the Colombians would not have to be paid – they simply joined methamphetamine with cocaine shipments. This fact meant no additional money was needed for airplanes, pilots, boats and bribes; they used the existing infrastructure to pipeline the new product.[85]

Until this point, the Sinaloa Cartel had been a joint venture between Guzmán and Ismael Zambada García; the methamphetamine business would be Guzmán's alone. He cultivated his own ties to China, Thailand and India to import the necessary precursor chemicals. Throughout the mountains of the states of Sinaloa, Durango, Jalisco, Michoacán and Nayarit, Guzmán constructed large methamphetamine laboratories and rapidly expanded his organization.[85]

Guzmán's nomadic existence allowed him to nurture contacts throughout the country. He was now operating in 17 of the 31 Mexican states. With his business expanding, he placed his trusted friend Ignacio Coronel Villarreal in charge of methamphetamine production; this way Guzmán could continue being the boss of bosses. Coronel Villarreal proved so reliable in the Guzmán business that he became known as the "Crystal King".[100]

First escape and second arrest

First escape: 2001

While still in prison in Mexico, Guzmán was indicted in San Diego on U.S. charges of money laundering and importing tons of cocaine into California, along with his Sinaloa attorney Humberto Loya-Castro, or Licenciado Perez ("Lawyer Perez"), who was charged with bribing Mexican officials on Sinaloa's behalf and making sure that any cartel members arrested were released from custody.[88][101] After a ruling by the Supreme Court of Mexico made extradition between Mexico and the United States easier, Guzmán bribed guards to aid his escape. On 19 January 2001, Francisco "El Chito" Camberos Rivera, a prison guard, opened Guzmán's electronically operated cell door, and Guzmán got into a laundry cart that maintenance worker Javier Camberos rolled through several doors and eventually out the front door. He was then transported in the trunk of a car driven by Camberos out of the town. At a petrol station, Camberos went inside, but when he came back, Guzmán was gone on foot into the night. According to officials, 78 people have been implicated in his escape plan.[85] Camberos is in prison for his assistance in the escape.[14]

The police say Guzmán carefully masterminded his escape plan, wielding influence over almost everyone in the prison, including the facility's director, who is now in prison for aiding in the escape.[14] One prison guard who came forward to report the situation at the prison disappeared 7 years later, and was presumed to have been killed on the orders of Guzmán.[14] Guzmán allegedly had the prison guards on his payroll, smuggled contraband into the prison and received preferential treatment from the staff. In addition to the prison-employee accomplices, police in Jalisco were paid off to ensure he had at least 24 hours to get out of the state and stay ahead of the military manhunt. The story told to the guards being bribed not to search the laundry cart was that Guzmán was smuggling gold, ostensibly extracted from rock at the inmate workshop, out of the prison. The escape allegedly cost Guzmán $2.5 million.[85][102]

Manhunt: 2001–2014

Mexican cartel wars

Since his 2001 escape from prison, Guzmán had wanted to control the Ciudad Juárez crossing points, which were in the hands of the Carrillo Fuentes family of the Juárez Cartel.[85] Despite a high degree of mistrust between the two organizations, the Sinaloa and Juárez cartels had a working agreement at the time. Guzmán convened a meeting in Monterrey with Ismael Zambada García ("El Mayo"), Juan José Esparragoza Moreno ("El Azul") and Arturo Beltrán Leyva. In this meeting, they discussed killing Rodolfo Carrillo Fuentes, who was in charge of the Juárez Cartel at the time. On 11 September 2004, Rodolfo, his wife and two young children were visiting a Culiacán shopping mall. While leaving the mall, escorted by police commander Pedro Pérez López, the family was ambushed by members of Los Negros, assassins for the Sinaloa Cartel. Rodolfo and his wife were killed; the policeman survived.[85]

The city was no longer controlled only by the Carrillo Fuentes family. Instead, the city found itself as the front line in the Mexican Drug War and would see homicides skyrocket as rival cartels fought for control. With this act, Guzmán was the first to break the nonaggression "pact" the major cartels had agreed to, setting in motion the fighting between cartels for drug routes that has claimed more than 60,000 lives since December 2006.[103][104][105]

When Mexican President Felipe Calderón took office in December 2006, he announced a crackdown on cartels by the Mexican military to stem the increasing violence.[106] After four years, the additional efforts had not slowed the flow of drugs or the killings tied to the drug war.[106] Of the 53,000 arrests made as of 2010, only 1,000 involved associates of the Sinaloa Cartel, which led to suspicions that Calderón was intentionally allowing Sinaloa to win the drug war, a charge Calderón denied in advertisements in Mexican newspapers, pointing to his administration's killing of top Sinaloa deputy "Nacho" Coronel as evidence.[106] Sinaloa's rival cartels saw their leaders killed and syndicates dismantled by the crackdown, but the Sinaloa gang was relatively unaffected and took over the rival gangs' territories, including the coveted Ciudad Juárez-El Paso corridor, in the wake of the power shifts.[98]

Conflict with Beltrán Leyva Cartel

A Newsweek investigation alleges that one of Guzmán's techniques for maintaining his dominance among cartels included giving information to the DEA and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement that led to the arrests of his enemies in the Juárez Cartel, in addition to information that led to the arrests of some of the top Sinaloa leaders.[88] The arrests were speculated by some to have been part of a deal Guzmán struck with Calderón and the DEA, in which he intentionally gave up some of his purported Sinaloa colleagues to U.S. agents in exchange for immunity from prosecution, while perpetuating the idea that the Calderón government was heavily pursuing his organization during the cartel crackdown.[107]

This became a key factor influencing the break between the Sinaloa Cartel and the Beltrán Leyva brothers, five brothers who served as Guzmán's top lieutenants, primarily working for the cartel in the northern region of Sinaloa.[108][109] Sinaloa lawyer Loya-Castro, who like Guzmán had been wanted on federal charges in the United States since 1993, voluntarily approached the DEA offering them information in 1998, eventually signing paperwork as a formal informant in 2005, and his U.S. indictment was thrown out in 2008.[88] Loya-Castro's leaks to the DEA led to the dismantling of the Tijuana Cartel, as well as the Mexican Army's arrest of Guzmán's lieutenant and the top commander of the Beltrán Leyva organization, Alfredo Beltrán Leyva (also known as El Mochomo, or "Desert Ant"), in Culiacán in January 2008, with Guzmán believed to have given up El Mochomo for various reasons.[88][107][109] Guzmán had expressed concerns with Alfredo Beltrán's lifestyle and high-profile actions for some time before his arrest. After El Mochomo's arrest, authorities said he was in charge of two hit squads, money laundering, transporting drugs and bribing officials.[108][110]

That high-profile arrest was followed by the arrest of 11 Beltrán Leyva hit squad members in Mexico City, with police noting that the arrests were the first evidence that Sinaloa had expanded into the capital city.[108][111] U.S. Ambassador to Mexico Tony Garza called the arrests a "significant victory" in the drug war.[108] With Alfredo in custody, his brother Arturo Beltrán Leyva took over as the brothers' top commander, but he was killed in a shootout with Mexican marines the next year.[109]

Whether Guzmán was responsible for Alfredo Beltrán's arrest is not known. However, the Beltrán Leyvas and their allies suspected he was behind it,[109] and after Alfredo Beltrán's arrest, a formal "war" was declared. An attempt on the life of cartel head Zambada's son Vicente Zambada Niebla (El Vincentillo) was made only hours after the declaration. Dozens of killings followed in retaliation for that attempt.[85] The Beltrán Leyva brothers ordered the assassination of Guzmán's son, Édgar Guzmán López, on 8 May 2008, in Culiacán, which brought massive retaliation from Guzmán. They were also in conflict over the allegiance of the Flores brothers, Margarito and Pedro, leaders of a major, highly lucrative cell in Chicago responsible for distributing over two tons of cocaine every month.[112] The Mexican military claims that Guzmán and the Beltrán Leyva brothers were at odds over Guzmán's relationship with the Valencia brothers in Michoacán.[85]

Following the killing of Guzmán's son Édgar, violence increased. From 8 May through the end of the month, over 116 people were murdered in Culiacán, 26 of them police officers. In June 2008, over 128 were killed; in July, 143 were slain.[85] An additional deployment of 2,000 troops to the area failed to stop the turf war. The wave of violence spread to other cities such as Guamúchil, Guasave and Mazatlán.

However, the Beltrán Leyva brothers were involved in some double-dealing of their own. Arturo and Alfredo had met with leading members of Los Zetas in Cuernavaca, where they agreed to form an alliance to fill the power vacuum. They would not necessarily go after the main strongholds, such as the Sinaloa and Gulf Cartel; instead, they would seek control of southern states like Guerrero (where the Beltrán Leyvas already had a big stake), Oaxaca, Yucatán and Quintana Roo. They worked their way into the center of the country, where no single group had control.[85] The Beltrán Leyva organization allied with the Gulf Cartel and its hit squad Los Zetas against Sinaloa.[111]

The split was officially recognized by the U.S. government on 30 May 2008. On that day, it recognized the Beltrán Leyva brothers as leaders of their own cartel. President George W. Bush designated Marcos Arturo Beltrán Leyva and the Beltrán Leyva Organization as subject to sanction under the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act ("Kingpin Act"),[85][113] which prohibits people and corporations in the U.S. from conducting businesses with them and freezes their U.S. assets.

First manhunt

Guzmán was known among drug lords for his longevity and evasion of authorities, assisted by alleged bribes to federal, state and local Mexican officials.[11][14][114] Despite the progress made in arresting others in the aftermath of Guzmán's escape, including a handful of his foremost logistics and security men, the huge military and federal police manhunt failed to capture Guzmán for years. In the years between his escape and capture, he was Mexico's most-wanted man.[115] His elusiveness from law enforcement made him a near-legendary figure in Mexico's narcotics folklore; stories abounded that Guzmán sometimes strolled into restaurants, his bodyguards confiscating peoples' cellphones, he ate his meal, and then left after paying everyone's tab.[116] Rumors circulated of Guzmán being seen in different parts of Mexico and abroad.[117] For more than thirteen years, Mexican security forces coordinated many operations to re-arrest him, but their efforts were largely in vain as Guzmán appeared to be steps ahead from his captors.[118]

Although his whereabouts were unknown, the authorities thought that he was likely hiding in the "Golden Triangle" (Spanish: Triángulo Dorado), an area that encompasses parts of Sinaloa, Durango, and Chihuahua in the Sierra Madre region. The region is a major producer of marijuana and opium poppies in Mexico,[119] and its remoteness from the urban areas makes it an attractive territory for the production of synthetic drugs in clandestine laboratories and for its mountains that offer potential hideouts.[120][121][122] Guzmán reportedly commanded a sophisticated security circle of at least 300 informants and gunmen resembling the manpower equivalent to those of a head of state. His inner circle would help him move around through several isolated ranches in the mountainous area to avoid capture.[117][123] He usually escaped from law enforcement using armored cars, aircraft, and all-terrain vehicles, and was known to employ sophisticated communications gadgetry and counterespionage practices.[123][124] Since many of these locations in the Golden Triangle are only accessible via single-track dirt roads, local residents easily detected the arrival of law enforcement or any outsiders. Their distrust towards non-residents and their aversion towards the government, alongside a combination of bribery and intimidation, helped keep the locals loyal to Guzmán and the Sinaloa Cartel in the area. According to law enforcement intelligence, attempting to have launched an attack to capture Guzmán by air would have had similar results; his security circle would have warned him of the presence of an aircraft 10 minutes away from Guzmán's location, giving him ample time to escape the scene and avoid arrest. In addition, his gunmen reportedly carried surface-to-air missiles that may bring down aircraft in the area.[123]

Second arrest: 2014

Although Guzmán had hidden for long periods in remote areas of the Sierra Madre mountains without being captured, the arrested members of his security team told the military he had begun venturing out to Culiacán and the beach town of Mazatlán.[99] A week before he was caught, Guzmán and Zambada were reported to have attended a family reunion in Sinaloa.[125] On 16 February 2014, the Mexican military followed the bodyguards' tips to Guzmán's former wife's house, but they had trouble ramming the steel-reinforced front door, which allowed Guzmán to escape through a system of secret tunnels that connected six houses, eventually moving south to Mazatlán.[99] He had planned to stay a few days in Mazatlán to see his twin baby daughters before retreating to the mountains.[126]

On 22 February 2014, at around 6:40 AM,[127] Mexican authorities arrested Guzmán at a hotel in a beachfront area on Mazatlán malecon, following an operation by the Mexican Navy, with joint intelligence from the DEA and the U.S. Marshals Service.[114][128] A few days before his capture, Mexican authorities had been raiding several properties owned by members of the Sinaloa Cartel who were close to Guzmán throughout the state of Sinaloa.[129][130][131] The operation leading to his capture began at 3:45 AM, when ten pickup trucks of the Mexican Navy carrying over 65 Marines made their way to the resort area. Guzmán was hiding at the Miramar condominiums, located at #608 on Avenida del Mar.[132][133] Mexican and U.S. federal agents had leads that the drug lord had been at that location for at least two days, and that he was staying on the condominium's fourth floor, in Room 401. When the Mexican authorities arrived at the location, they quickly subdued Carlos Manuel Hoo Ramírez, one of Guzmán's bodyguards, before quietly making their way to the fourth floor by the elevators and stairs. Once they were at Guzmán's front door, they broke into the apartment and stormed its two rooms. In one of the rooms was Guzmán, lying in bed with his wife (former beauty queen Emma Coronel Aispuro).[133][134] Their two daughters were reported to have been at the condominium during the arrest.[135] Guzmán tried to resist arrest physically,[133] but he did not attempt to grab a rifle he had close to him.[136][137] Amid the quarrel with the marines, the drug lord was hit four times. By 6:40 AM, he was arrested, taken to the ground floor, and walked to the condominium's parking lot, where the first photos of his capture were taken.[133][138] His identity was confirmed through a fingerprint examination immediately following his capture.[139] He was then flown to Mexico City for formal identification.[140] According to the Mexican government, no shots were fired during the operation.[129][141]

Guzmán was presented in front of cameras during a press conference at the Mexico City International Airport that afternoon,[142] and then he was transferred to the Federal Social Readaptation Center No. 1, a maximum-security prison in Almoloya de Juárez, State of Mexico, on a Federal Police Black Hawk helicopter. The helicopter was escorted by two Navy helicopters and one from the Mexican Air Force.[143][144] Surveillance inside the penitentiary and surrounding areas was increased by a large contingent of law enforcement.[145]

Reactions

Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto confirmed the arrest through Twitter and congratulated the Secretariat of National Defense (SEDENA), Secretariat of the Navy (SEMAR), Office of the General Prosecutor (PGR), the Federal Police, and the Centro de Investigación y Seguridad Nacional (CISEN) for Guzmán's capture.[11][146][147] In the United States, Attorney General Eric Holder said Guzmán had caused "death and destruction of millions of lives across the globe" and called the arrest "a landmark achievement, and a victory for the citizens of both Mexico and the United States".[114] Colombia's President Juan Manuel Santos telephoned Peña Nieto and congratulated him for the arrest of Guzmán, highlighting its importance in the international efforts against drug trafficking.[148] Colombia's Defense Minister, Juan Carlos Pinzón, congratulated Mexico on Guzmán's arrest and stated that his capture "contributes to eradicate this crime (drug trafficking) in the region".[149] The Guatemalan President Otto Pérez Molina congratulated the Mexican government for the arrest.[150] Costa Rica's President Laura Chinchilla congratulated the Mexican government through Twitter for the capture too.[151] The French government extended its congratulations on 24 February and supported the Mexican security forces in their combat against organized crime.[152] News of Guzmán's capture made it to the headlines of many media outlets across the U.S., Latin America, and Europe.[153][154] On Twitter, Mexico and Guzmán's capture were trending topics throughout most of 22 February 2014.[155]

Bob Nardoza, a spokesman for the U.S. attorney's office for the District Court for the Eastern District of New York, announced that U.S. authorities plan to seek the extradition of Guzmán for several cases pending against him in New York and other United States jurisdictions.[156]

Charges and imprisonment

Guzmán was imprisoned at Federal Social Readaptation Center No. 1, area #20, Hallway #1, on the same day of his capture on 22 February 2014.[157] The area where he lived was highly restricted; the cells are without windows, inmates are not allowed to interact with each other, and they are not permitted to contact their family members.[158] His cell was close to those of José Jorge Balderas (alias "El JJ"), former lieutenant of the Beltrán Leyva Cartel, and Jaime González Durán (alias "El Hummer"), a former leader of Los Zetas drug cartel. Miguel Ángel Guzmán Loera, one of his brothers, was in one of the other units.[159][160] Guzmán was alone in his cell, and had one bed, one shower, and a single toilet. His lawyer was Óscar Quirarte. Guzmán was allowed to receive visits from members of his family every nine days from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. (if approved by a judge), and was granted by law the right to receive MXN$638 (about US$48) every month to buy products for personal hygiene.[159][161] He lived under 23 hours of solitary confinement with one hour of outdoor exposure. He was only allowed to speak with people during his judicial hearings (the prison guards that secured his cell were not allowed to speak with him). Unlike the other inmates, Guzmán was prohibited from practicing sport or cultural activities. These conditions were court-approved and could only be changed if a federal judge decided to amend them.[161]

On 24 February, the Mexican government formally charged Guzmán for drug trafficking, a process that slowed down his possible extradition to the U.S. The decision to initially file only one charge against him showed that the Mexican government was working on preparing more formal charges against Guzmán, and possibly including the charges he faced before his escape from prison in 2001. The kingpin also faced charges in at least seven U.S. jurisdictions, and U.S. officials filed for his extradition.[162][163] Guzmán was initially granted an injunction preventing immediate extradition to the United States.[164] On 25 February, a Mexican federal judge set the trial in motion for drug-related and organized crime charges,[165] On 4 March 2014, a Mexican federal court issued a formal charge against Guzmán for his involvement in organized crime.[166][167]

On 5 March 2014, a Mexico City federal court rejected Guzmán's injunction against extradition to the U.S. on the grounds that the U.S. officials had not formally requested his extradition from Mexico. The court said that if the U.S. files a request in the future, Guzmán can petition for another injunction.[168] The court had until 9 April 2014 to issue a formal declaration of the injunction's rejection, and Guzmán's lawyers could appeal the court's decision in the meantime.[169] The same day that the injunction was rejected, another federal court issued formal charges against Guzmán, totaling up to five different Mexican federal courts where he was wanted for drug trafficking and organized crime charges.[170] The court explained that although Guzmán faces charges in several different courts, he cannot be sentenced for the same crime twice because that would violate Article 23 of the Constitution of Mexico.[171]

On 17 April 2014, the Attorney General of Mexico, Jesús Murillo Karam, said that Mexico had no intention of extraditing Guzmán to the U.S. even if a formal request were to be presented. He said he wished to see Guzmán face charges in Mexico, and expressed his disagreement with how the U.S. cuts deals with extradited Mexican criminals by reducing their sentences (as in Vicente Zambada Niebla's case) in exchange for information.[172]

On 16 July 2014, Guzmán reportedly helped organize a five-day hunger strike in the prison in cooperation with inmate and former drug lord Edgar Valdez Villarreal (alias "La Barbie"). Over 1,000 prisoners reportedly participated in the protest and complained of the prison's poor hygiene, food, and medical treatment. The Mexican government confirmed that the strike took place and that the prisoners' demands were satisfied, but denied that Guzmán or Valdez Villarreal were involved in it given their status as prisoners in solitary confinement.[173][174]

On 25 September 2014, Guzmán and his former business partner Zambada were indicted by the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York in Brooklyn.[175] According to the court documents, both of them conspired to kill Mexican law enforcement officers, government officials, and members of the Mexican Armed Forces. Among the people killed under the alleged orders of Guzmán were Roberto Velasco Bravo (2008), the chief of Mexico's organized crime investigatory division; Rafael Ramírez Jaime (2008), the chief of the arrest division of the Attorney General's Office; Rodolfo Carrillo Fuentes (2004), former leader of the Juárez Cartel, among other criminals from the Tijuana, Los Zetas, Beltrán Leyva, and Juárez crime syndicates.[176] The court alleged that Guzmán used professional assassins to carry out "hundreds of acts of violence, including murders, assaults, kidnappings, assassinations and acts of torture".[177] In addition, it alleged that he oversaw a drug-trafficking empire that transported multi-ton shipments of narcotics from South America, through Central America and Mexico, and then to the U.S., and that his network was facilitated by corrupt law enforcement and public officials.[176] It also alleged that Guzmán laundered more than US$14 billion in drug proceeds along with several other high-ranking drug lords.[178][179]

On 11 November 2014, a federal court in Sinaloa granted Guzmán an injunction for weaponry charges after the judge determined that the arrest was not carried out the way the Mexican Navy reported it.[180] According to law enforcement, the Navy apprehended Guzmán after they received an anonymous tip on an armed individual in the hotel where he was staying. However, no evidence of the anonymous tip was provided. The judge also determined that the investigations leading to his arrest were not presented in court. He determined that law enforcement's version of the arrest had several irregularities because the Navy did not have a raid warrant when they entered the premises and arrested Guzmán (when he was not the subject matter of the anonymous tip in the first place).[181]

On 20 January 2015, Guzmán requested another injunction through his lawyer Andrés Granados Flores to prevent his extradition to the U.S.[182] His defense argued that if he were to be extradited and judged in a foreign court, his constitutional rights expressed in Articles 1, 14, 16, 17, 18 and 20 of the Constitution of Mexico would be violated.[183] The decision of his defense was made after Attorney General Murillo Karam said at a press conference that the U.S. was pushing to formally request his extradition.[184] The PGR and Mexico's Secretariat of Foreign Affairs stated that Guzmán had a provisional arrest with extradition purposes from the U.S. government since 17 February 2001, but that the formal proceedings to officiate the extradition were not realized because investigators considered that the request was outdated and believed it would have been difficult to gather potential witnesses.[185] Murillo Karam said that the Mexican government would process the request when they deemed it appropriate.[186] He asked for a second injunction preventing his extradition on 26 January. Mexico City federal judge Fabricio Villegas asked federal authorities to confirm in 24 hours if there was a pending extradition request against Guzmán.[187] In a press conference the following day, Murillo Karam said that he was expecting a request from Washington, but said that they would not extradite him until he faces charges and completes his sentences in Mexico. If all the charges are added up, Guzmán may receive a sentence between 300 and 400 years.[188][189]

Second escape and third arrest

Second escape: 2015

On 11 July 2015, Guzmán escaped from Federal Social Readaptation Center No. 1.[189] Guzmán was last seen by security cameras at 20:52 hours near the shower area in his cell. The shower area was the only part of his cell that was not visible through the security camera.[190][191] After the guards did not see him for twenty-five minutes on surveillance video, personnel went looking for him.[192] When they reached his cell, Guzmán was gone. It was discovered he had escaped through a tunnel leading from the shower area to a house construction site 1.5 km (0.93 mi) away in a Santa Juanita neighborhood.[193][194] The tunnel lay 10 m (33 ft) deep underground, and Guzmán used a ladder to climb to the bottom. The tunnel was 1.7 m (5 ft 7 in) tall and 75 cm (30 in) in width. It was equipped with artificial light, air ducts, and high-quality construction materials.[190] In addition, a motorcycle was found in the tunnel, which authorities think was used to transport materials and possibly Guzmán himself.[195][196]

Second manhunt: 2015–2016

The escape of Guzmán triggered a wide-range manhunt.[197] According to Mexico's National Security Commissioner Monte Alejandro Rubido García, the manhunt was instituted immediately in the surrounding area by putting up several checkpoints and air searches by helicopter.[198] The entire prison was put on lockdown and no one was allowed to enter or leave.[199] The search was then extended to other federal entities: Mexico City, the State of Mexico, Morelos, Puebla, Guerrero, Michoacán, Querétaro, Hidalgo and Tlaxcala. However, most of the military officers involved in the search were sent to the State of Mexico.[200] The Mexican government also issued an international warning to prevent Guzmán from escaping the country through airports, border checkpoints, or ports. Interpol and other security organizations were alerted to the possibility of him escaping into another country.[201] Flights at the Toluca International Airport were cancelled, while soldiers occupied parts of Mexico City International Airport.[191] Out of the 120 employees that were working at the prison that night, eighteen that worked in the area of Guzmán's cell were initially detained for questioning.[202] By the afternoon, a total of 31 people had been called in for questioning. The director of the prison, Valentín Cárdenas Lerma, was among those detained.[203]

When the news of the escape broke, President Peña Nieto was heading to a state visit in France along with several top officials from his cabinet and many others.[204] The Secretary of the Interior Miguel Ángel Osorio Chong, who was already in France waiting for them, returned to Mexico after learning of Guzmán's prison break.[205][206] Peña Nieto returned to Mexico on 17 July.[207] In a press conference, Peña Nieto said he was shocked by Guzmán's escape, and promised that the government would carry out an intensive investigation to see if officials had collaborated in the prison break. In addition, he claimed that Guzmán's escape was an "affront" to the Mexican government, and that they would not spare any resources in trying to recapture him.[208] Peña Nieto, however, was severely criticized for the incident, and media outlets pointed out that this incident was among the administration's most embarrassing episodes. Critics stated that Guzmán's escape highlighted the high levels of corruption within the government, and questioned the government's ability to combat the country's organized crime groups.[209][210]

On 13 July 2015, Osorio Chong met with members of the cabinet that specialize in security and law enforcement intelligence to discuss the escape of Guzmán, and scheduled a press conference that day. The objective of the meeting and the conference was to analyze the actions the government employed to recapture him. Among them were Rubido García, Arely Gómez González, the Attorney General of Mexico and Eugenio Imaz Gispert, head of the Center for Research and National Security.[211][212] At the press conference, the government placed a $60 million MXN bounty (approximately US$3.8 million) for information that leads to Guzmán's arrest.[213]

A number of officials were indicted; of these, three were police officers employed within the Division of Intelligence, and another two were employed by CISEN.[214]

Colombian assistance

Officials of the Mexican government appealed to three Colombian Police retired generals for assistance in the closure of issues relating to Guzmán, according to a report dated to 1 August 2015.[215] Among them is Rosso José Serrano, a decorated officer and one of the masterminds behind the dismantling of the Cali Cartel and Medellín Cartel and Luis Enrique Montenegro, protagonist in the arrests of Miguel and Gilberto Rodríguez Orejuela. They suggested particular Colombian strategies like creation of special search units ("Bloques de Búsqueda" or Search Blocs), specialized investigation and intelligence units, like DIJIN (Directorate of Criminal Investigation and Interpol) and DIPOL (Directorate of Police Intelligence) and new laws about money laundering and asset forfeiture.[215][216] After the third capture of Guzmán, it was revealed that the Government of Colombia had sent a team of 12 officials to assist the Mexican authorities on tracking down Guzmán.[217]

Kate del Castillo meeting

Mexican actress Kate del Castillo was first approached by Guzmán's lawyers in 2014,[218] after having published an open letter to Guzmán in 2012 in which she expressed her sympathy and requested him to "traffic in love" instead of in drugs; Guzmán reached out again to del Castillo after his 2015 escape,[219][220] and allegedly sought to cooperate with her in making a film about his life.[218][221] American actor Sean Penn heard about the connection with Ms. del Castillo through a mutual acquaintance, and asked if he might come along to do an interview.[222]

On 2 October, del Castillo and Penn visited Guzmán for seven hours at his hideout in the mountains, with Penn interviewing the fugitive for Rolling Stone magazine.[221] Guzmán, who had never before acknowledged his drug trafficking to a journalist, told Penn he had a "fleet of narco-submarines, airplanes, trucks and boats" and that he supplied "more heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine and marijuana than anybody else in the world".[221]

Guzmán had a close call in early October 2015, several days after the meeting with Penn and Kate del Castillo.[223][219] An unnamed Mexican official confirmed that the meeting helped authorities locate Guzmán,[224] with cell phone interceptions and information from American authorities[223] directing Mexican Marines to a ranch near Tamazula, Durango, in the Sierra Madre mountains in western Mexico.[225] The raid on the ranch was met with heavy gunfire and Guzmán was able to flee. The Attorney General of México declared that "El Chapo ran away through a gully and, although he was found by a helicopter, he was with two women and a girl and it was decided not to shoot".[226][227] The two women were later revealed to be Guzmán's personal chefs, who had traveled with him to multiple safe houses. At one point, Guzmán reportedly carried a child on his arms "obscuring himself as a target".[223]

Third arrest: 2016

According to the official report published by the Mexican Navy, citizens reported "armed people" in a house at the coastal city of Los Mochis in northern Sinaloa, which was then placed under surveillance for one month.[228] Monitored communications indicated the home was being prepared for the arrival of "Grandma" or "Aunt", which authorities suspected was code for a high-priority potential target.[223] After the gunmen returned to the house, placing a large order for tacos at a nearby restaurant and picking up the order in a white van after midnight,[223] the residence was raided in the early hours of 8 January 2016,[228][229] in Operation Black Swan, by 17 marines from the Mexican Navy's Special Forces with support from the Mexican Army and the Federal Police[230][231] – but Guzmán and a lieutenant escaped through a secret tunnel, emerging 1.5 km away and stealing a vehicle at gunpoint.

A statewide alert was issued for the stolen vehicle, and the Federal Police located and intercepted it about 20 km south of Los Mochis near the town of Juan José Ríos.[232] Guzmán attempted to bribe the officers with offers of cash, properties, and offers of jobs.[223][232] When the officers refused, Guzmán told them "you are all going to die". The four police officers sent pictures of Guzmán to their superiors, who were tipped that 40 assassins were on their way to free Guzmán.[223] To avoid this counter-attack by cartel members, the policemen were told to take their prisoners to a motel on the outskirts of town to wait for reinforcements,[232][233] and later, hand over the prisoners to the marines.[234] They were subsequently taken to Los Mochis airport for transport to Mexico City, where Guzmán was presented to the press at the Mexico City airport and then flown by a Navy helicopter to the same maximum-security prison from which he escaped in July 2015.[235]

During the raid, five gunmen were killed, six others arrested, and one Marine was wounded.[230] The Mexican Navy said that they found two armored cars, eight assault rifles, including two Barrett M82 sniper rifles, two M16 rifles with grenade launchers and a loaded rocket-propelled grenade launcher.[236]

Reactions

Mexican Secretary of the Interior Miguel Ángel Osorio Chong was hosting a reunion with Mexico's ambassadors and consuls when he received a notice from the President on Guzmán's capture.[237] He returned a few moments later with Secretary of National Defense Salvador Cienfuegos Zepeda, Secretary of Navy Vidal Francisco Soberón Sanz and Secretary of Foreign Affairs Claudia Ruiz Massieu.[237] Osorio Chong then announced the capture to the diplomats by reading the President's tweet which resulted in applause and chants of Viva México, Viva el Presidente Peña and Viva las Fuerzas Armadas (Long live Mexico, Long live President Peña, Long live our Military Forces).[238] This was followed by a spontaneous rendition of the National Anthem by the crowd.[237][238]

Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos congratulated Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto for the capture of Guzmán. Santos stated that "Guzmán's capture is a success, a great blow against organized crime, and drug trafficking", adding that "finally, this individual (Guzmán), like all criminals, will find what he deserves in the eyes of justice, and we celebrate that the Mexican authorities have recaptured this criminal".[239] Loretta Lynch, United States Attorney General, praised Mexican authorities "who have worked tirelessly in recent months to bring Guzmán to justice".

Arrest of Emma Coronel Aispuro

Emma Coronel Aispuro, 31, the wife of Joaquín Guzmán, was arrested at Dulles International Airport on 22 February 2021, accused of helping her husband run his cartel and plot his escape from prison in 2015. Coronel was charged with conspiracy to distribute cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin and marijuana in the U.S.[240] She has not been charged with any crimes in Mexico, although her father, Inés Coronel Barreras, and her brother, Édgar Coronel, were arrested on drug charges and allegations of helping Guzman′s first prison escape. Inés Coronel was arrested in 2013 and sentenced to ten years, 3 months in prison in 2017. Édgar Coronel Aispuru was arrested in 2015 and is imprisoned in Aguaruto prison, Sinaloa.[241]

In 2019 Emma Coronel launched a clothing line and appeared on U.S. reality television.[242]

United States extradition and prosecution

Mexico formally launched a renewed process of extradition to the United States two days after Guzmán was recaptured on 8 January 2016 after his second prison escape.[219][243][244] Guzmán's lawyers mounted "numerous and creative injunctions" to prevent extradition.[223][245] Vicente Antonio Bermúdez Zacarías was a federal judge involved in Guzmán's extradition proceedings, and he was assassinated on 17 October 2016 while jogging near Mexico City.[246]

Guzmán was wanted in Chicago, San Diego, New York City, New Hampshire, Miami, and Texas, in addition to having indictments in at least seven different U.S. federal courts.[247][248][249] Charges in the United States include drug trafficking with intent to distribute, conspiracy association, organized crime against health, money laundering, homicide, illegal possession of firearms,[250] kidnapping, and murder in Chicago, Miami, New York, and other cities.[251][252][253] A critical requirement for extradition was that the U.S. must guarantee that they would not sentence Guzmán to death if he were found guilty of homicide charges.[247][254][255]

On 19 January 2017, Guzmán was extradited to the U.S. to face the charges and turned over to the custody of HSI and DEA agents.[18][256][257][258] He was housed at the maximum-security wing of the Metropolitan Correctional Center, New York located in Manhattan.[259] He pled not guilty on 20 January to a 17-count indictment in the United States District Court in New York.[260] U.S. District Judge Brian Cogan scheduled his trial for 5 November 2018, when jury selection began.[261] According to the prosecutors, juror anonymity and an armed escort were necessary, even if Guzmán is in isolation, due to his history of having jurors and witnesses murdered.[262] The judge agreed to keep jurors anonymous and to have Guzmán transported to and from the courthouse by U.S. Marshals and sequestered from the public while in the courthouse.[263] Opening arguments began Tuesday 13 November,[264] and closing arguments took place on 31 January 2019.[265] Guzmán was found guilty of all counts on 12 February 2019, and was sentenced on 17 July 2019 to life in prison plus 30 years[19][266][267] and ordered to forfeit more than $12.6 billion.[1] He was imprisoned in ADX Florence, the most secure US supermax prison, under Federal Register Number 89914-053.[268][269]

Personal and family criminal activities

Guzmán's family is heavily involved in drug trafficking. Several members of his family, including his brother, one of his sons, and a nephew were killed by Sinaloa's archrival cartels, Los Zetas and the Beltrán Leyva Organization.[87]

In 1977, Guzmán married Alejandrina María Salazar Hernández in a small ceremony in the town of Jesús María, Sinaloa. The couple had four children: César, Ivan Archivaldo, Jesús Alfredo and Alejandrina Gisselle. He set them up in a ranch home in Jesús María.

When he was 30 years old, El Chapo fell in love with a bank clerk, Estela Peña of Nayarit, whom he kidnapped and with whom he had sexual relations. They later married.

In the mid-1980s, Guzmán married once more, to Griselda López Pérez, with whom he had four more children: Édgar, Joaquín Jr., Ovidio, and Griselda Guadalupe.[85][270]

Guzmán's sons followed him into the drug business, and his third wife, López Pérez, was arrested in 2010, in Culiacán.[271] Édgar died after a 2008 ambush in a shopping center parking lot, in Culiacán, Sinaloa. Afterwards, police found more than 500 AK-47 bullet casings at the scene. Ovidio was arrested on 5 January 2023 and extradited to U.S. on September 15 that year, and Joaquín was arrested in El Paso, Texas on July 25, 2024, along with Ismael "El Mayo" Zambada.

In November 2007, Guzmán married an 18-year-old American beauty queen, Emma Coronel Aispuro, the daughter of one of his top deputies, Inés Coronel Barreras, in Canelas, Durango.[272][273][274] In August 2011, she gave birth to twin girls, Maria Joaquina and Emali Guadalupe, in Los Angeles County Hospital, in California.[275][276] Emma Coronel Aispuro pleaded guilty on 6 June 2021, to charges in the U.S. and admitted that she helped her husband run his multibillion-dollar criminal empire.[277]

On 1 May 2013, Guzmán's father-in-law, Inés Coronel Barreras, was captured by Mexican authorities in Agua Prieta, Sonora, with no gunfire exchanged. U.S. authorities believe Coronel Barreras was a "key operative" of the Sinaloa Cartel who grew and smuggled marijuana through the Arizona border area.[273]

On 15 February 2005, Guzmán's son Iván Archivaldo, known as "El Chapito", was arrested in Guadalajara on money laundering charges.[278] He was sentenced to five years in a federal prison but released in April 2008, after a Mexican federal judge, Jesús Guadalupe Luna, ruled that there was no proof his cash came from drugs other than that he was a drug lord's son.[279] Luna and another judge were later suspended on suspicion of unspecified irregularities in their decisions, including Luna's decision to release "El Chapito".[279]

Guzmán's brother Arturo, known as "El Pollo", was killed in prison in 2004.[87]

Another of Guzmán's sons, Jesús Alfredo Guzmán Salazar, known as "El Gordo" ("The Fat One"), then 23 years old, was suspected of being a member of the cartel and was indicted on federal charges of drug trafficking in 2009 with Guzmán, by the U.S. District Court of Northern Illinois, which oversees Chicago.[278][280] Authorities described Guzmán Salazar as a growing force within his father's organization and directly responsible for Sinaloa's drug trade between the U.S. and Mexico and for managing his billionaire father's growing list of properties. Guzmán Salazar and his mother, Guzmán's former wife María Alejandrina Salazar Hernández, were both described as key operatives in the Sinaloa Cartel and added to the U.S.'s financial sanction list under the Kingpin Act on 7 June 2012.[280][281][282]

The U.S. Treasury Department described Salazar as Guzmán's wife, in its sanction against her, and described Guzmán as her husband.[282] The month before, the U.S. Treasury Department had announced sanctions against Guzmán's sons Iván Guzmán Salazar and Ovidio Guzmán López under the Kingpin Act.[283] Guzmán's second wife, Griselda López Pérez, was also sanctioned by the U.S. under the Kingpin Act and described as Guzmán's wife.[284]

Jesús Guzmán Salazar was reported to have been detained by Mexican Marines in an early morning raid, in the western state of Jalisco on 21 June 2012.[285] Months later, however, the Mexican Attorney General's Office announced the Marines had arrested the wrong man and that the man captured was actually Félix Beltrán León, who said he was a used-car dealer, not the drug lord's son.[278] U.S. and Mexican authorities blamed each other for providing the inaccurate information that led to the arrest.[278]

In 2012, Alejandrina Gisselle Guzmán Salazar, a 31-year-old pregnant physician and Mexican citizen from Guadalajara, was said to have claimed she was Guzmán's daughter as she crossed the U.S. border into San Diego.[286] She was arrested on fraud charges for entering the country with a false visa.[271] Unnamed officials said the woman was the daughter of María Alejandrina Salazar Hernández but did not appear to be a major figure in the cartel. She had planned to meet the father of her child in Los Angeles and give birth in the United States.[271]

On the night of 17 June 2012, Obied Cano Zepeda, a nephew of Guzmán's, was gunned down by unknown assailants at his home in the state capital of Culiacán, while hosting a Father's Day celebration.[287] The gunmen, who were reportedly carrying AK-47 rifles, also killed two other guests and left another seriously injured.[287]

Obied was a brother of Luis Alberto Cano Zepeda (alias "El Blanco")'s, another nephew of Guzmán's who worked as a pilot drug transporter for the Sinaloa cartel.[288] The latter was arrested by the Mexican military in August 2006.[288] InSight Crime notes that Obied's murder may have been either a retaliation attack by Los Zetas, for Guzmán's incursions into their territory, or a brutal campaign heralding Los Zetas' presence in Sinaloa.[289]

Even after Guzman's arrest, the Sinaloa Cartel remained the primary drug distributor (in 2018) in the U.S. among Mexican cartels, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.[290]

In popular culture

Literature

Martin Corona, the chief assassin for a rival cartel of Sinaloa's who mistakenly killed a priest when aiming at Guzmán, published a tell-all memoir titled Confessions of a Cartel Hit Man in 2017.[291]

Music

Several Mexican narcocorridos (narco ballads) narrate the exploits of Guzmán[292][293][294][295][296][297] and his organization. Additionally, some American artists have made songs with references to Guzmán, such as Uncle Murda, Skrillex, YG, Gucci Mane,[298] and The Game.[299][300]

Television

In 2017, Netflix and Univision began co-producing the series El Chapo about the life of Guzmán.[301] The series premiered on Sunday, 23 April 2017 and was followed by a 20-minute Facebook Live after-show titled "El Chapo Ilimitado".[302][303]

Guzmán is also portrayed by Alejandro Edda in the Netflix television series Narcos: Mexico.

See also

Footnotes

References

- ^ a b Hong, Nicole (17 July 2019). "El Chapo Sentenced to Life in U.S. Prison". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 17 July 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ "Mexico offers $3.8m reward in hunt for escaped drug lord". BBC News. 13 July 2015. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f "Narcotics Rewards Program: Joaquín Guzmán-Loera". U.S. Department of State. 2015. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "Federal Bureau of Prisons Inmate Locator". Federal Bureau of Prisons. United States Department of Justice. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

BOP Register Number: 89914-053

- ^ Basu, Tanya (12 July 2015). "What to Know About Mexican Drug Lord 'El Chapo' Guzman". TIME. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ McKay, Hollie (10 November 2018). "Manipulation, fear, snitches, and a new cell: Behind the scenes as El Chapo goes to trial". Fox News. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ a b Otero, Silvia. "EU: "El Chapo" es el narco más poderoso del mundo". El Universal. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ "Where 7 Mexican drug cartels are active within the U.S." The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ Santiago Wills (18 April 2013). "Mexican Cartel Presence Threatens European Security, Europol Says". Fusion. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014.

- ^ "Powerful Sinaloa cartel's business unlikely to be slowed by arrest of boss 'El Chapo' Guzmán". Fox News. 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Partlow, Joshua; Miroff, Nick (5 July 2005). "World's top drug trafficker arrested in Mexico, U.S. official says". The Washington Post. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Joaquin Guzman Loera". Forbes. Archived from the original on 3 August 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ Vardi, Nathan (15 June 2011). "Joaquin Guzmán Has Become The Biggest Drug Lord Ever". Forbes Magazine. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l De Cordoba, Jose (13 June 2009). "The Drug Lord Who Got Away". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Drug lord 'El Chapo' Guzmán captured in Mexico". Fox News. 1 December 2006. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ "Mexican drug lord Joaquin 'El Chapo' Guzman escapes jail". BBC News. 12 July 2015. Archived from the original on 13 August 2018. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ Ahmed, Azam (8 January 2016). "El Chapo, Escaped Drug Lord, Has Been Recaptured, Mexican President Says". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Joaquin 'El Chapo' Guzman Being Extradited to the US". ABC News. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ a b "El Chapo sentenced to life in prison." Archived 17 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine BBC News 17 July 2019.

- ^ "Mexican drug lord 'El Chapo' begins life term in Colorado 'Supermax' prison". Reuters. 21 July 2019. Archived from the original on 21 July 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

"We can confirm that Joaquin Guzman is in the custody of the Federal Bureau of Prisons at United States Penitentiary (USP) Administrative Maximum (ADX) Florence, located in Florence, Colorado," the U.S. Bureau of Prisons said in a statement.

- ^ Beith, Malcolm 2010, p. xvii.

- ^ Tuckman, Jo 2012, p. 22.

- ^ "Narcotics Rewards Program: Joaquin Guzmán-Loera". Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs at the United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ Feuer, Alan (17 January 2019). "How El Chapo Escaped in a Sewer, Naked With His Mistress". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ Stephey, M.J. (13 March 2009). "Joaquin Guzmán Loera: Billionaire Drug Lord". TIME magazine. Archived from the original on 18 January 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ "Libre, cumple el 'Chapo' 56 años de edad". Ríodoce (in Spanish). 4 April 2013. Archived from the original on 8 August 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ a b Hernández, Anabel 2012, p. 57.

- ^ Beith, Malcolm 2010, p. 50-54.

- ^ Macqueen, Angus (9 January 2016). "El Chapo was the world's most wanted drug lord. But has his brutal reign finally come to an end?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ^ Vorobyov, Niko (2019) Dopeworld. Hodder, UK. p. 228

- ^ a b c d Reyes, Gerardo (2013). "The Eternal Fugitive: El Chapo Territory". Univision. Archived from the original on 23 January 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ a b Beith, Malcolm 2010, p. 51.

- ^ "Who Is El Chapo Guzmán, Mexico's Most Elusive Drug Lord?". Fusion. Univision. 2013. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ Beith, Malcolm 2010, p. xvii-xx.

- ^ Beith, Malcolm 2010, p. 54-55.

- ^ Beith, Malcolm 2010, p. 53.