Jefferson Airplane

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2022) |

Jefferson Airplane | |

|---|---|

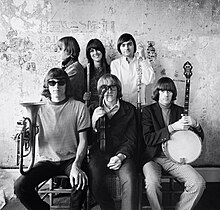

Jefferson Airplane photographed by Herb Greene in his dining room, San Francisco, late 1966; top row from left: Jack Casady, Grace Slick, Marty Balin; bottom row from left: Jorma Kaukonen, Paul Kantner, Spencer Dryden | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Years active | 1965–1973, 1989, 1996 |

| Labels | |

| Spinoffs | |

| Past members | Signe Toly Anderson Marty Balin Bob Harvey Paul Kantner Jorma Kaukonen Jerry Peloquin Skip Spence Jack Casady Spencer Dryden Grace Slick Joey Covington Papa John Creach John Barbata David Freiberg |

| Website | jeffersonairplane.com |

Jefferson Airplane was an American rock band formed in San Francisco, California, in 1965. One of the pioneering bands of psychedelic rock, the group defined the San Francisco Sound and was the first from the Bay Area to achieve international commercial success. They headlined the Monterey Pop Festival (1967), Woodstock (1969), Altamont Free Concert (1969), and the first Isle of Wight Festival (1968)[1] in England. Their 1967 breakout album Surrealistic Pillow was one of the most significant recordings of the Summer of Love. Two songs from that album, "Somebody to Love" and "White Rabbit", are among Rolling Stone's "500 Greatest Songs of All Time".[2][3]

The October 1966 to February 1970 lineup of Jefferson Airplane, consisting of Marty Balin (vocals), Paul Kantner (guitar, vocals), Grace Slick (vocals, keyboards), Jorma Kaukonen (lead guitar, vocals), Jack Casady (bass), and Spencer Dryden (drums), was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1996.[4] Balin left the band in 1971.[5] After 1972, Jefferson Airplane effectively split into two groups. Kaukonen and Casady moved on full-time to their own band, Hot Tuna. Slick, Kantner, and the remaining members of Jefferson Airplane recruited new members and regrouped as Jefferson Starship in 1974, with Balin eventually joining them. Jefferson Airplane received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2016.

History

[edit]1965–1966: Formation and early development

[edit]In 1962, 20-year-old Marty Balin recorded two singles for Challenge Records, neither of which was successful.[6][7] He then played in a folk quartet, the Town Criers, from April 1963 to June 1964.[8] With the Beatles-led British Invasion, Balin was inspired by the emerging folk rock genre to form a group in March 1965 that would follow that lead, as well as opening a nightclub for them to perform.[9][10] With a group of investors, he purchased a former pizza parlor on Fillmore Street in San Francisco and converted it into a club called the Matrix.[11][9][12][13] Meanwhile, he searched for like-minded musicians to form his group.[14]

Balin met fellow folk guitarist and singer Paul Kantner during a hootenanny at another local club, the Drinking Gourd, and invited Kantner to join him in putting together a band.[14][15][16] A native San Franciscan, Kantner had started out performing on the Bay Area folk circuit in the early 1960s, alongside fellow folkies Jerry Garcia and David Crosby.[17][15] He cited folk groups like the Kingston Trio and the Weavers as strong early influences. He briefly moved to Los Angeles in 1964 to work in a folk duo with future Airplane/Starship member David Freiberg (who subsequently joined Quicksilver Messenger Service).[18]

Balin and Kantner then recruited other musicians to form the house band at the Matrix. They hired bluegrass acoustic bassist Bob Harvey and former Marine Band drummer Jerry Peloquin.[16][19] Both Kantner and Balin wanted the group to have a female singer.[19] After hearing vocalist Signe Toly Anderson at the Drinking Gourd, Balin invited her to be the group's co-lead singer. Anderson sang with the band for a year and performed on their first album before departing in October 1966 after the birth of her first child.[20]

They still needed a lead guitarist.[21] Kantner recruited an old friend, blues guitarist Jorma Kaukonen, who auditioned for the group and joined them in June, completing the original lineup.[22] Originally from Washington, D.C., Kaukonen had moved to California in the early 1960s and met Kantner at Santa Clara University in 1962. Kaukonen was invited to jam with the new band, and although initially reluctant to join, he was won over after playing his guitar through a tape delay device that was part of the sound system used by Ken Kesey for his Acid Test parties.

Kaukonen came up with the band name "Jefferson Airplane".[23] It was based on the nickname "Blind Thomas Jefferson Airplane," which was given to Kaukonen by his friend Richmond "Steve" Talbot, inspired by the name of one of Kaukonen's influences, bluesman Blind Lemon Jefferson.[24][25] According to Kaukonen, "The band was coming up with all these really stupid names and I said, 'If you want something really silly, try Jefferson Airplane.'"[22]

At a music shop near the Matrix, Peloquin encountered Matthew Katz, a music manager who was searching for a band to work with.[26] Katz had beforehand offered to manage the Town Criers, Balin's previous group, but was turned down because of disagreements over his terms.[26] Peloquin reintroduced Katz to Balin, who had been trying to find a manager for Jefferson Airplane.[16] Katz enticed the band by mentioning that he had access to an unreleased Bob Dylan song, "Lay Down Your Weary Tune", and they appointed him as their manager,[27] although they did not officially sign a contract with Katz until December 1965.[28]

After rehearsing throughout the summer, the group made its first public appearance as Jefferson Airplane at the opening night of The Matrix on August 13, 1965.[9][29] The band expanded from its folk roots, drawing inspiration from the Beatles, the Byrds and the Lovin' Spoonful, and gradually developed a more pop-oriented electric sound.[citation needed] Later that month, John L. Wasserman of the San Francisco Chronicle praised the band's "musical approach and style"—noting their blend of folk, blues, and rock and roll—and remarked, "Although there are but hints at this time, it is entirely possible that this will be the new direction of contemporary pop music."[30]

A few weeks after the group started performing, Peloquin departed because of conflicts with his bandmates, in part because of his disdain for their drug use.[31] Although he was not a drummer, singer-guitarist Skip Spence (who later co-founded Moby Grape) was then invited to replace Peloquin.[32] Spence quickly adapted and made his debut at the Matrix in September.[33] In October 1965, after the other members decided that Bob Harvey's bass playing was not up to par, he was replaced by guitarist-bassist Jack Casady, an old friend of Kaukonen from Washington, D.C.[34] Casady played his first gig with the Airplane on October 30 in the Harmon Gym at the University of California, Berkeley.[35]

The group's performance skills improved rapidly and they soon gained a strong following in and around San Francisco, aided by reviews from music journalist Ralph J. Gleason, the jazz critic of the San Francisco Chronicle. After seeing them at the Matrix, Gleason wrote in the September 13 edition of his "On the Town" column that the band, still without a record deal, would "obviously record for someone" eventually.[31] Gleason's support raised the band's profile considerably, and within three months Katz was fielding offers from recording companies, although they had yet to perform outside the San Francisco Bay Area.[31]

Two significant early concerts featuring the Airplane were held in late 1965. The first was the historic dance at the Longshoremen's Hall in San Francisco on October 16, 1965, the first of many "happenings" in the Bay Area, where Gleason first saw them perform. At this concert they were supported by a local folk-rock group, the Great Society, that featured Grace Slick as lead singer, and it was here that Kantner met Slick for the first time.[37] A few weeks later, on November 6, they appeared at a benefit concert for the San Francisco Mime Troupe, the first of many promotions by rising Bay Area entrepreneur Bill Graham, who later became the band's manager.[38]

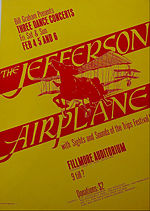

By late 1965, Jefferson Airplane, under Katz's management, had turned down recording offers from Capitol, Valiant, Fantasy, Elektra, and London.[39] In November 1965, Jefferson Airplane signed a recording contract with RCA Victor, which included a then unheard-of advance of $25,000 (equivalent to $242,000 in 2023).[40] Before this, they had recorded a demo for Columbia Records of "The Other Side Of This Life" with Harvey on bass, which was immediately rejected by the label.[39] On December 10, 1965, the Airplane played at the first Bill Graham-promoted show at the Fillmore Auditorium, supported by the Great Society and others. The Airplane also appeared at numerous Family Dog shows promoted by Chet Helms at the Avalon Ballroom.[37]

The group's first single was Balin's "It's No Secret" (a tune he wrote with Otis Redding in mind); the B-side was "Runnin' Round This World", the song that led to the band's first clash with RCA Victor over the lyric "The nights I've spent with you have been fantastic trips". After their debut LP was completed in March 1966, Skip Spence quit the band and he was eventually replaced by Spencer Dryden, who played his first show with the Airplane at the Berkeley Folk Festival on July 4, 1966. Dryden had previously played with a Los Angeles group called the Ashes, which later became the Peanut Butter Conspiracy.[41]

Original manager Katz was fired in August, sparking a long-running legal battle that continued until 1987, and Balin's friend and roommate Bill Thompson was installed as road manager and temporary band manager.[42] It was Thompson, a friend and staunch supporter of the band and a former Chronicle staffer, who had convinced reviewers Ralph Gleason and John Wasserman to see the band at the Matrix.[43] Thanks to Gleason's influence, Thompson was able to book the group for appearances at the Monterey Jazz Festival.[44]

The group's debut LP Jefferson Airplane Takes Off was released on August 15, 1966.[45] The album was dominated by Balin, who provided most of the lead vocals and had a hand in writing all of the original material, including "It's No Secret" and "Come Up the Years."[46] It also contained covers of "Tobacco Road", Dino Valente's "Let's Get Together", and "Chauffeur Blues", which became a signature tune for Anderson.[47] RCA Victor initially pressed only 15,000 copies, but it sold more than 10,000 in San Francisco alone, prompting the label to reprint it. For the re-pressing, the company deleted "Runnin' Round This World" (which had appeared on early mono pressings), because executives objected to the word "trip" in the lyrics. For similar reasons, RCA Victor substituted altered versions for two other tracks: "Let Me In", changing the line "I gotta get in/you know where" to "you shut your door/now it ain't fair." In the same song, they also switched the lyric "Don't tell me you want money" to "Don't tell me it ain't funny". "Run Around" was also edited, changing the line "flowers that sway as you lay under me" to "flowers that sway as you stay here by me". The original pressings of the LP featuring "Runnin' 'Round This World" and the uncensored versions of "Let Me In" and "Run Around" are collectors items.

Signe Anderson gave birth to her daughter in May 1966,[20][48] and in October she announced her departure from the band. Her final performance with the Airplane took place at the Fillmore on October 15, 1966.[20] A recording of the performance, subtitled Signe's Farewell, was released in 2010.[49]

1966–1967: Commercial breakthrough

[edit]

The following night, Anderson's successor, Grace Slick made her first appearance.[50] Slick had seen the Airplane at the Matrix in 1965, and her previous group, the Great Society, had often supported them in concert.[51]

Slick's recruitment proved pivotal to the Airplane's commercial breakthrough—she possessed a powerful and supple contralto voice that complemented Balin's and was well-suited to the group's amplified psychedelic music. A former model, her good looks and stage presence greatly enhanced the group's live impact. "White Rabbit" was written by Slick while she was still with The Great Society. The first album she recorded with Jefferson Airplane was Surrealistic Pillow,[52] its 1967 breakout album.[53] Slick provided two songs from her previous group: her own "White Rabbit" and "Somebody to Love", written by her brother-in-law Darby Slick. Both songs became breakout successes for Jefferson Airplane and have ever since been associated with that band.[52]

The Great Society had recorded an early version of "Somebody to Love" (under the title "Someone to Love") as the B-side of their only single, "Free Advice", produced by Sylvester Stewart (soon to become famous as Sly Stone). It reportedly took more than 50 takes to achieve a satisfactory rendition. The Great Society split up in late 1966 and played its last show on September 11. Soon after, Slick was asked to join Jefferson Airplane by Casady (whose musicianship was a major influence on her decision) and her Great Society contract was bought out for $750.[52]

In December 1966, Jefferson Airplane was featured in a Newsweek article about the booming San Francisco music scene, one of the first in a welter of similar media reports that prompted a massive influx of young people to the city and contributed to the commercialization of hippie culture.[54]

Around the beginning of 1967, Bill Graham took over from Thompson as manager. In January the group made its first visit to the East Coast. On January 14, alongside the Grateful Dead and Quicksilver Messenger Service, Jefferson Airplane headlined the "Human Be-In", the famous all-day "happening" in Golden Gate Park, one of the key events leading up to the "Summer of Love".

During this period the band gained its first international recognition when rising British pop star Donovan, who saw them during his stint on the U.S. West Coast in early 1966, mentioned the Airplane in his song "The Fat Angel", which subsequently appeared on his Sunshine Superman LP.[55]

The group's second LP record|LP, Surrealistic Pillow, recorded in Los Angeles with producer Rick Jarrard in 13 days at a cost of $8,000, launched the Airplane to international fame. Released in February 1967, the LP entered the Billboard 200 album chart on March 25 and remained there for over a year, peaking at No. 3. It sold over one million copies, and was awarded a gold disc.[56] The name "Surrealistic Pillow" was suggested by the album's informal producer, Jerry Garcia, when he mentioned that, as a whole, the album sounded "as surrealistic as a pillow is soft." Although RCA did not acknowledge Garcia's contributions to the album with a production credit, he is listed in the album's credits as "spiritual advisor."[57]

In addition to the group's two best-known tracks, "White Rabbit" and "Somebody to Love", the album featured "My Best Friend" by former drummer Skip Spence, Balin's driving blues-rock songs "Plastic Fantastic Lover" and "3/5 of a Mile in 10 Seconds", and the atmospheric Balin-Kantner ballad "Today". A reminder of their earlier folk incarnation was Kaukonen's solo acoustic guitar tour de force "Embryonic Journey" (his first composition), which referenced contemporary acoustic guitar masters such as John Fahey and helped to establish the popular genre exemplified by acoustic guitarist Leo Kottke.[citation needed]

The first single from the album, "My Best Friend", failed to chart, but the next two rocketed the group to prominence. Both "Somebody to Love" and "White Rabbit" became major U.S. hits, the former reaching No. 5 and the latter No. 8 on the Billboard singles chart. By late 1967 the Airplane were national and international stars and had become one of the hottest groups in America. Grace Slick biographer Barbara Rowes called the album "a declaration of independence from the establishment [-] What Airplane originated was a romanticism for the electronic age. Unlike the highly homogenized harmonies of the Beach Boys, Airplane never strived for a synthesis of its divergent sensibilities. Through [-] each song, there remain strains of the individual styles of the musicians [creating] unusual breadth and original interplay within each structure".[58]

This phase of the Airplane's career peaked with their famous performance at the Monterey International Pop Festival in June 1967.[59] Monterey showcased leading bands from several major music "scenes" including New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and the United Kingdom, and the resulting TV and film coverage gave national (and international) exposure to groups that had previously had only regional fame.[60] Two songs from the Airplane's set were subsequently included in the D. A. Pennebaker film documentary of the event.[61]

In August 1967, the Airplane performed in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, at two free outdoor concerts, along with fellow Bay Area band the Grateful Dead. The first concert was held in downtown Montreal at Place Ville Marie, and the second was at the Youth Pavilion of Expo 67.[62]

The Airplane also benefited greatly from appearances on national network TV shows such as The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson on NBC and The Ed Sullivan Show on CBS. The Airplane's famous appearance on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour performing "White Rabbit" and "Somebody to Love" was videotaped in color and augmented by developments in video techniques. It has been frequently re-screened and is notable for its pioneering use of the Chroma key process to simulate the Airplane's psychedelic light show.[63]

1967–1970: Heavier sound and improvisation

[edit]After Surrealistic Pillow, the group's music underwent a significant transformation. The band's third LP, After Bathing at Baxter's, was released in December, 1967[64] and eventually peaked in the charts at No. 17.[65] Its famous cover, drawn by artist and cartoonist Ron Cobb,[66] depicts a flying machine (constructed around an idealized version of a typical Haight-Ashbury district house) soaring above the chaos of American commercial culture.[67][68] Recorded over a period of more than four months, with little input from nominal producer Al Schmitt, the new album demonstrated the group's growing engagement with psychedelic rock. Although the previous LP had consisted entirely of standard-length pop songs, After Bathing at Baxter's was dominated by long multi-part suites. However, "A Small Package of Value Will Come to You, Shortly" was a musique concrète-style audio collage.[69]

After Bathing at Baxter's also marked the ascendency of Kantner and Slick as the band's chief composers and the concurrent decline of Balin's influence and involvement. The other members, gravitating toward a harder-edged style, openly criticized Balin for his ballad-oriented compositions. Balin was also reportedly becoming increasingly disenchanted with the "star trips" and "inflated egos" generated by the band's runaway commercial success.[70]

In contrast to "White Rabbit" and "Somebody to Love", "The Ballad of You and Me and Pooneil" only peaked at No. 42 and "Watch Her Ride" stalled at No. 61. However, both singles reached the Top 40 in Cash Box magazine. None of the band's subsequent singles reached the Billboard Top 40 and several failed to chart at all. AM Top 40 radio became wary of a group that had scored a hit with a song that contained thinly veiled drug references and whose singles were often deemed too controversial, so Jefferson Airplane never again enjoyed the kind of widespread AM radio support that served as a prerequisite for top-ten hits.[71]

In February 1968, manager Bill Graham was fired after Slick delivered an "either he goes or I go" ultimatum.[72] Bill Thompson took over as permanent manager and consolidated the group's financial security, establishing Icebag Corp. to oversee the band's publishing interests and purchasing a 20-room mansion at 2400 Fulton Street across from Golden Gate Park near the Haight-Ashbury, which became the band's office and communal residence. Bill Laudner was hired as road manager.[73]

In mid-1968, the group was photographed for a Life magazine story on "The New Rock", appearing on the cover of the June 28, 1968 edition. They undertook their first major tour of Europe in August–September 1968, playing alongside the Doors in the Netherlands, England, Germany and Sweden.[72] In a notorious incident at a concert in Amsterdam, while Jefferson Airplane was performing "Plastic Fantastic Lover", Doors singer Jim Morrison, under the influence of a combination of drugs that fans had given him, appeared on stage and began dancing "like a pinwheel". As the group played faster and faster, Morrison spun around wildly until he finally fell senseless on the stage at Balin's feet. Morrison was unable to perform his set with the Doors and was hospitalized; keyboardist Ray Manzarek sang all the vocals.[74] It was also during this tour that Slick and Morrison allegedly engaged in a brief sexual relationship, described in Somebody to Love?, Slick's 1998 autobiography.[citation needed]

Jefferson Airplane's fourth LP, Crown of Creation (released in September 1968), was a commercial success, peaking at No. 6 on the album chart and receiving a gold certification. Slick's "Lather", which opens the album, is said to be about her affair with drummer Spencer Dryden and his 30th birthday.[72] "Triad", a David Crosby composition,[37] had been rejected by the Byrds because they deemed its subject matter (a ménage à trois) to be too "hot." Slick's searing sexual and social-commentary anthem "Greasy Heart" was released as a single in March 1968. A few tracks recorded for the LP were omitted from the album but were later included as bonus tracks, including the Slick/Frank Zappa collaboration "Would You Like a Snack?"[citation needed]

Jefferson Airplane's appearance on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in October of 1968 caused a minor stir when Slick appeared in blackface and raised her fist in the Black Panther Party's salute after singing "Crown of Creation".[75]

In November 1968, the band played "House at Pooneil Corners" and part of "Somebody to Love" on the roof of the Schuyler Hotel on West 45th Street in Manhattan. It was filmed for the D. A. Pennebaker film One P.M. at the invitation of French filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard. As no permit had been obtained, the performance was stopped by the police just as occurred with the Beatles' famous rooftop concert about two months later, as depicted in the documentary Let It Be (1970). Several people, including Balin and actor Rip Torn, were arrested.[76][77]

In February 1969, RCA released the live album Bless Its Pointed Little Head, which was culled from 1968 performances at the Fillmore West on October 24–26 and the Fillmore East on November 28–30. It became the band's fourth Top 20 album, peaking at No. 17.[citation needed]

Hot Tuna began during a break in Jefferson Airplane's touring schedule in early 1969 while Slick recovered from throat node surgery that left her unable to perform. Kaukonen, Casady, Kantner and drummer Joey Covington played several shows around San Francisco, including Jefferson Airplane's original club, The Matrix, before Jefferson Airplane resumed performing. Their early repertoire was derived mainly from Jefferson Airplane material that Kaukonen (the band's frontman) sang and covers of American ragtime artist Jelly Roll Morton and country blues artists such as Reverend Gary Davis, Bo Carter and Blind Blake. From October 1969 to November 1970, Hot Tuna (also including Balin and, following Kantner's departure, a dedicated rhythm guitarist in their electric performances until November 1970) performed as the opening act to Jefferson Airplane with a combination of both electric and acoustic sets.[citation needed]

In April 1969, sessions began for Jefferson Airplane's next album, Volunteers, using new 16-track facilities at the Wally Heider Studio in San Francisco. This proved to be the last album by the classic lineup of the group. The album's release was delayed following the band's conflict with the label over the content of songs such as "We Can Be Together" and the planned title of the album, Volunteers of Amerika, a title derived from the Volunteers of America charity, and the term was in vogue in 1969 as an ironic expression of dissatisfaction with Americ. After the charity group objected, the title was shortened to Volunteers.[78]

A few days after the band headlined at a free concert in New York's Central Park in August 1969, they performed in what Slick called the "morning maniac music" slot at the Woodstock Festival, for which the group was joined by noted British session keyboard player Nicky Hopkins. When interviewed about Woodstock by Jeff Tamarkin in 1992, Kantner recalled it with fondness but Slick and Dryden did not.[79] Immediately after their Woodstock performance, the band taped an appearance on The Dick Cavett Show and played a few songs. Other guests on that same episode were David Crosby, Stephen Stills and Joni Mitchell.[80]

The new album was finally released in the United States in November 1969. It continued Jefferson Airplane's run of Top 20 LPs, peaking at No. 13 and attaining a RIAA gold certification early in 1970. It was their most political venture, showcasing the group's vocal opposition to the Vietnam War and documenting their reaction to the changing political atmosphere in the United States. The best-known tracks include "Volunteers", "We Can Be Together", "Good Shepherd" and the post-apocalyptic "Wooden Ships", which Kantner cowrote with Crosby and Stills, and which Crosby, Stills & Nash also recorded on their debut album.[81]

RCA raised objections to the phrase "up against the wall, motherfucker!" in the lyrics of Kantner's "We Can Be Together", but the group managed to prevent it from being censored on the album, pointing out that RCA had already allowed the offending word to be included on the cast album of the rock musical Hair. In addition, the song had the line "in order to survive, we steal, cheat, lie, forge, fuck, hide and deal", which was also kept on the album. The group sang the song with both lines intact during their Dick Cavett Show appearance, thus becoming the first known persons to utter those words on national broadcast television.[82] In the printed lyrics that accompanied the album, the line was transcribed as "up against the wall fred".[83]

In December 1969, Jefferson Airplane played at the Altamont Free Concert at Altamont Speedway in California.[84] Following the Grateful Dead's withdrawal from the program,[85] they became the only band to perform at all three of the iconic rock festivals of the 1960s—Altamont, Monterey Pop and Woodstock. Headlined by the Rolling Stones, the concert was marred by violence. Balin was punched on stage during a scuffle with Hells Angels members who had been hired to act as security guards.[86] The event became notorious for the fatal stabbing of teenager Meredith Hunter in front of the stage by Hells Angels after he drew a revolver during the Rolling Stones' performance.[87][88]

1970–1974: Decline and dissolution

[edit]Dryden was dismissed from the band in February 1970 by a unanimous vote of the other members.[89] Dryden had political differences with the band and was experiencing burnout after four years on the "acid merry-go-round". He was also deeply disillusioned by the events at Altamont, which, he later recalled, "did not look like a bunch of happy hippies in streaming colors. It looked more like sepia-toned Hieronymus Bosch." He took time off before returning to music the following year as Mickey Hart's replacement in the New Riders of the Purple Sage. Dryden was replaced by Hot Tuna drummer Joey Covington, who had already contributed additional percussion to Volunteers and performed select engagements with Jefferson Airplane as a touring second drummer in 1969. Later that year, the band was further augmented by the addition of veteran jazz violinist Papa John Creach, a friend of Covington who officially joined Hot Tuna and Jefferson Airplane for their fall tour in October 1970.[citation needed]

Touring continued throughout 1970, but the group's only new recordings that year were the single "Mexico" backed with the B-side "Have You Seen the Saucers?" Slick's "Mexico" was an attack on President Richard Nixon's Operation Intercept, which had been implemented to curtail the flow of marijuana into the United States. "Have You Seen the Saucers" marked the beginning of the science-fiction themes that Kantner explored in much of his subsequent work, including Blows Against the Empire, his first solo album. Released in November 1970 and credited to "Paul Kantner/Jefferson Starship," this prototypical iteration of Jefferson Starship (alternatively known as the Planet Earth Rock and Roll Orchestra) included Crosby, Graham Nash, Grateful Dead members Jerry Garcia, Bill Kreutzmann and Mickey Hart, session luminary Harvey Brooks, David Freiberg, Slick, Covington and Casady. Blows Against the Empire peaked at No. 20 in the United States and was the first rock album nominated for the Hugo Award.[citation needed]

Jefferson Airplane ended 1970 with their traditional Thanksgiving Day engagement at the Fillmore East (marking the final performances of the short-lived Creach-era septet) and the release of their first compilation album, The Worst of Jefferson Airplane, which continued their unbroken run of post-1967 chart success, reaching No. 12 on the Billboard album chart.[citation needed]

1971 was a year of major upheaval for Jefferson Airplane. Slick and Kantner had begun a relationship in 1970, and on January 25, 1971, their daughter China Wing Kantner ("Wing" was Slick's maiden name) was born.[90][91] Slick's divorce from her first husband had recently become official, but she and Kantner agreed that they did not wish to marry.[citation needed]

In April 1971, Balin officially left Jefferson Airplane after disassociating himself from the group following the fall 1970 tour. Although he had remained a key part of live performances after the band's creative direction shifted from brooding love songs, the evolution of the polarized Kantner/Slick and Kaukonen/Casady cliques—compounded by an emerging drinking problem—had finally left him the odd man out. Following the traumatic death of Janis Joplin, he began to pursue a healthier lifestyle; Balin's study of yoga and abstention from drugs and alcohol further distanced him from the other members of the group, whose drug intake continued unabated. This further complicated the recording of their long-overdue follow-up to Volunteers; Balin had recently completed several new songs, including "Emergency" and the elongated R&B-infused "You Wear Your Dresses Too Short," both of which later appeared on archival releases.[citation needed]

On May 13, 1971, Slick was injured in a near-fatal automobile crash when her car slammed into a wall in a tunnel near the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. The accident happened while she was drag racing with Kaukonen; both were driving at over 100 miles per hour, and Kaukonen claims that he "saved her life" by pulling her from the car.[92] Slick's recuperation took a few months, forcing the Airplane to curtail their touring commitments. In the meantime, Slick recorded a comic song ("Never Argue with a German If You're Tired or European Song") about the incident for the new album.[citation needed]

In September 1971, Bark was released. With cover art depicting a dead fish wrapped in an A&P-style grocery bag, it was both the final album owed to RCA under the band's existing contract and the inaugural release on the band's Grunt Records vanity label. Manager Bill Thompson had struck a deal with RCA to allow Jefferson Airplane to run Grunt Records as they saw fit while retaining RCA's distribution. The single "Pretty As You Feel", excerpted from a longer jam with members of Santana and featuring lead vocals by Joey Covington, its principal composer, was the last Jefferson Airplane chart hit, peaking at No. 60 in Billboard and No. 35 in Cashbox. The album rose to No. 11 in Billboard, higher than Volunteers, Blows Against the Empire and Hot Tuna's second album, First Pull Up, Then Pull Down, released three months before Bark in June.[citation needed]

Despite the band's continued success, major creative and personal divisions persisted between the Slick-Kantner and Kaukonen-Casady factions. (Kaukonen's "Third Week In The Chelsea," from Bark, chronicles the thoughts he was having about leaving the band.) These problems continued to be exacerbated by the band's escalating cocaine use and Slick's alcohol use disorder. Consequently, while the band played several dates in August in support of Bark (including two concerts in the New York metropolitan area and a show apiece in Detroit and Philadelphia), no tour was planned. Following a private concert/party commemorating the formation of Grunt Records at San Francisco's Friends and Relations Hall in September, the band would not reconvene until several Midwestern engagements in January 1972.[citation needed]

Jefferson Airplane held together long enough to record one more album, Long John Silver, begun in April 1972 and released in July. By this time the various members were thoroughly engaged with their various solo projects. Following the release of Kantner and Slick's Sunfighter in November 1971 and Creach's eponymous solo debut in December 1971, Hot Tuna released their first studio album and third opus Burgers in February 1972; meanwhile, Covington immersed himself in various Grunt Records projects, including his own solo album, Fat Fandango, released in 1973, and the sessions for Black Kangaroo's debut album led by multi-instrumentalist Peter Kaukonen, Jorma's younger brother. Covington was either dismissed from the band or left of his own volition shortly after the sessions commenced.[93]

With Hot Tuna drummer Sammy Piazza deputizing on one track, Covington (who had already recorded two drum parts) was soon replaced by former Turtles and CSNY drummer John Barbata, who ultimately played on most of the album.[93] Barbata was recommended to the group by David Crosby.[94] Long John Silver is notable for its cover, which folded out into a humidor, which the inner photo depicted as storing cigars (which may have been filled with marijuana). Despite middling reviews, the album rose to No. 20 in the United States, a significantly higher placement than Burgers (No. 68) or Sunfighter (No. 89).[citation needed]

The band began a proper national tour to promote Long John Silver in 1972, their first in nearly two years. Shortly before the tour commenced, David Freiberg (who had recently completed a prison sentence for marijuana possession after leaving Quicksilver Messenger Service) joined as a belated replacement for Balin. The East Coast leg of the tour included a major free concert in Central Park that drew over 50,000 attendees. They returned to the West Coast in September, playing concerts in San Diego, Hollywood, Phoenix and Albuquerque. The tour culminated in two shows at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco (September 21–22), both of which were recorded. At the end of the second show, the group was joined on stage by Balin, who sang lead vocals on "Volunteers" and the final song, "You Wear Your Dresses Too Short".[citation needed]

The Winterland shows were the last live performances by Jefferson Airplane[22] until their reunion in 1989. A new live album, Thirty Seconds Over Winterland, was culled from the tour and released in April 1973. Later that year, Kaukonen and Casady decided to focus on Hot Tuna as a full-time endeavor, effectively leaving the band; however, no official announcement was ever released. By December 1973, RCA had terminated the band's salaries, resulting in Freiberg being forced to draw unemployment to maintain his house payments.[95]

Following the commercially unsuccessful Baron von Tollbooth & the Chrome Nun (1973; credited to Kantner, Slick and Freiberg) and Manhole (1974; credited to Slick), Jefferson Airplane evolved into Jefferson Starship in January 1974.[96][97][98][99] The initial lineup consisted of the remaining members of Jefferson Airplane (Kantner, Slick, Freiberg, Barbata, Creach); bassist Peter Kaukonen (soon replaced by British multi-instrumentalist Pete Sears, a veteran of Creach's debut solo album and Manhole); and lead guitarist Craig Chaquico, a member of Grunt Records band Jack Traylor and Steelwind who contributed to the Kantner/Slick solo albums beginning with Sunfighter. They appropriated the name from Kantner's Blows Against the Empire, with Bill Thompson convincing the group that maintaining the connection was prudent from a business standpoint.[100] Reflecting the transition, the album Dragon Fly, released in September 1974, was credited to Slick, Kantner and Jefferson Starship.

Side projects and spin-off bands

[edit]Reunions and other performances, 1989–present

[edit]After the acrimonious events that resulted in Jefferson Starship's 1984 evolution into Starship, Kantner reunited with Balin (who joined Jefferson Starship in January 1975 following a guest appearance on Dragon Fly before leaving once more in 1978) and Casady in 1985 to form the KBC Band. They released their only album, KBC Band, in 1986 on Arista Records. On March 4, 1988, Slick made a cameo appearance during a Hot Tuna San Francisco performance at the Fillmore (with Kantner and Creach joining in), facilitating a potential reunion of Jefferson Airplane.[citation needed]

In 1989, the classic 1966–70 lineup of Jefferson Airplane reunited (with the exception of Dryden) for a tour and album. The self-titled album was released by Epic[101] to modest sales but the accompanying tour was considered a success.[98]

In 1996, the 1966–70 lineup of Jefferson Airplane was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, with Balin, Casady, Dryden, Kantner and Kaukonen attending[102] and performing.[103] Slick was absent.[102][104]

1998 saw the production and broadcast of a very popular episode of the hit VH1 documentary television series Behind the Music about Jefferson Airplane, directed by Bob Sarles. Band members Slick, Balin, Kantner, Kaukonen, Casady and Dryden were all interviewed for the episode, along with David Crosby, longtime Airplane manager Bill Thompson and China Kantner, daughter of Paul Kantner and Grace Slick.[citation needed]

In 2004, the film Fly Jefferson Airplane (directed by Bob Sarles) was released on DVD. It covers the years 1965–72 and includes then-recent interviews with band members and 13 complete songs.[citation needed]

Kaukonen and Casady performed a set at the 2015 Lockn' Festival to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Jefferson Airplane. They were joined by G.E. Smith, Rachael Price, Larry Campbell and Teresa Williams.[105] In 2016, Jefferson Airplane was given the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.[106] In 2022, Jefferson Airplane received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[107][108]

Spencer Dryden died of colon cancer on January 11, 2005.[109] Signe Anderson and Paul Kantner both died on January 28, 2016.[110] Marty Balin died on September 27, 2018.[111]

Members

[edit]- Paul Kantner – rhythm guitar, vocals (1965–1972, 1989, 1996; died 2016)

- Jorma Kaukonen – lead guitar, vocals (1965–1972, 1989, 1996)

- Marty Balin – vocals, rhythm guitar, percussion (1965–1971, 1989, 1996; died 2018)

- Signe Toly Anderson – vocals (1965–1966; died 2016)

- Bob Harvey – double bass (1965)

- Jerry Peloquin – drums (1965)

- Skip Spence – drums, percussion (1965–1966; died 1999)

- Jack Casady – bass, rhythm guitar (1965–1972, 1989, 1996)

- Grace Slick – vocals, piano, recorder, keyboards (1966–1972, 1989)

- Spencer Dryden – drums, percussion (1966–1970, 1996; died 2005)

- Joey Covington – drums, percussion (1970–1972; died 2013)

- Papa John Creach – violin, vocals (1970–1972; died 1994)

- John Barbata – drums, percussion (1972; died 2024)

- David Freiberg – vocals, rhythm guitar (1972)

Discography

[edit]- Jefferson Airplane Takes Off (1966)

- Surrealistic Pillow (1967)

- After Bathing at Baxter's (1967)

- Crown of Creation (1968)

- Bless Its Pointed Little Head (1969)

- Volunteers (1969)

- Bark (1971)

- Long John Silver (1972)

- Thirty Seconds Over Winterland (1973)

- Jefferson Airplane (1989)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Stutz, Colin (January 28, 2016). "Paul Kantner, Jefferson Airplane Co-Founder & Guitarist, Dies at 74". Billboard.com. Archived from the original on November 30, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ "500 Greatest Songs of All Time". Rolling Stone. April 7, 2011. Archived from the original on April 6, 2019. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ Greene, Jason Heller,Brittany Spanos,Simon Vozick-Levinson,Keith Harris,Andy (January 29, 2016). "Jefferson Airplane: 12 Essential Songs". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 11, 2024. Retrieved November 11, 2024.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lewis, Randy (September 28, 2018). "Marty Balin, co-founder of Jefferson Airplane, dies at 76". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ Hussain, Suhauna (September 28, 2018). "Jefferson Airplane co-founder Marty Balin dies at age 76". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on November 11, 2024. Retrieved November 11, 2024.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Swanson, Dave (September 29, 2018). "Top 10 Marty Balin Songs". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on June 24, 2022. Retrieved December 4, 2022.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b c Ruhlmann, William. "Jefferson Airplane: Artist Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on July 4, 2018. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, p. 11.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, p. 24.

- ^ Marks, Ben (October 16, 2017). "From Folk to Acid Rock, How Marty Balin Launched the San Francisco Music Scene". Collectors Weekly. Archived from the original on December 30, 2021. Retrieved December 4, 2022.

- ^ uao (June 5, 2005). "Artist Overview – Jefferson Airplane". Blogcritics Music. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ a b Lawrence, Wade; Parker, Scott. "Jefferson Airplane | 50 Years of Peace & Music". Bethel Woods Center for the Arts. Archived from the original on November 28, 2022. Retrieved December 4, 2022.

- ^ a b Balin, Marty (January 29, 2016). "Paul Kantner Remembered by Former Jefferson Airplane Bandmate Marty Balin: Exclusive". Billboard (Interview). Interviewed by Gary Graff. Archived from the original on December 5, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c Butterworth 2021, p. 15.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, p. 18.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "David Freiberg". Allmusic. Archived from the original on October 11, 2017.

- ^ a b Tamarkin 2003, p. 23.

- ^ a b c Unterberger, Richie. "Signe Anderson Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, p. 25.

- ^ a b Tamarkin 2003, p. 32.

- ^ "Jorma Kaukonen: A Brief History". JormaKaukonen.com. Archived from the original on November 27, 2009. Retrieved August 25, 2007.

- ^ Leonardi, Tom (October 5, 2016). "Music by local legend Richmond Talbot". KZFR. Archived from the original on February 23, 2020. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- ^ Butterworth 2021, pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b Tamarkin 2003, p. 33.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, p. 36.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, p. 40–41.

- ^ a b c Tamarkin 2003, p. 41.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, p. 42.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, p. 43.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, pp. 45, 49, 51.

- ^ Fenton 2006, p. 54; Tamarkin 2003, p. 46.

- ^ "Fillmore History". The Fillmore. Archived from the original on May 5, 2006. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ a b c Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 41 – The Acid Test: Psychedelics and a sub-culture emerge in San Francisco" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries. Archived from the original on November 9, 2011. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, pp. 54–55, 125–126.

- ^ a b Tamarkin 2003, p. 44.

- ^ Butterworth 2021, p. 16.

- ^ "The Peanut Butter Conspiracy - The Unofficial Web Site". www.peanutbutterconspiracy.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, pp. 81, 343.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, pp. xviii, 41.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, p. 83.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, p. 80; Fenton 2006, p. 31.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. "Takes Off Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on May 2, 2022. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- ^ Butterworth 2021, p. 22.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (January 31, 2016). "Signe Anderson, Original Jefferson Airplane Singer, Dead at 74". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 17, 2016. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. "Live at the Fillmore Auditorium 10/15/66: Late Show: Signe's Farewell". AllMusic. Archived from the original on December 5, 2017. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, p. 114.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, pp. 95, 106.

- ^ a b c Tamarkin 2003, p. 113.

- ^ Basner, Dave (May 11, 2017). "Hear The Powerful Isolated Vocals From Jefferson Airplane's Hits". KXIC Sports 800. Archived from the original on September 10, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ Hertzberg, Hendrik (August 13, 2013). "Newsweek's Glory Days (Mine, Too)". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Archived from the original on November 11, 2024. Retrieved November 11, 2024.

- ^ Sacher, Andrew (July 20, 2022). "Beyond "White Rabbit": Why Jefferson Airplane were one of psychedelic rock's greatest bands". brooklynvegan.com. Archived from the original on June 10, 2023. Retrieved December 2, 2024.

- ^ Murrells, Joseph (1978). The Book of Golden Discs (2nd ed.). London: Barrie and Jenkins Ltd. p. 224. ISBN 0-214-20512-6.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Rowes, Barbara (1980). Grace Slick. Doubleday. p. 74. ISBN 0-385-13390-1.

- ^ Tannenbaum, Rob (May 26, 2017). "The Oral History of Monterey Pop, Where Jimi Torched His Ax & Janis Became a Star: Art Garfunkel, Steve Miller, Lou Adler & More". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 11, 2024. Retrieved November 11, 2024.

- ^ Allen, Jim (June 16, 2017). "How the Monterey Pop Festival Changed Music Forever". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on November 11, 2024. Retrieved November 11, 2024.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, p. 141.

- ^ Whelan, John. "August 6, 1967: Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead performed at the Youth Pavilion at Expo 67". Expo 67 in Montreal. Archived from the original on October 5, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ Knopper, Steve (September 29, 2021). "'White Rabbit' Enters 'The Matrix': From Vague Pitch to 'Stunning' Result and 'Significant' Payday". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 12, 2024. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ After Bathing at Baxter's at AllMusic. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ^ "Chart History: Jefferson Airplane". Billboard. Retrieved June 6, 2024.

- ^ Fortin, Jacey (September 23, 2020). "Ron Cobb, a Pioneer in Science Fiction Design, Dies at 83". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ^ Wimpfheimer, Seth (September 2022). "Unsung | The Book of Seth | Jefferson Airplane - After Bathing At Baxter's". Head Heritage. Archived from the original on October 3, 2022. Retrieved December 10, 2022.

- ^ Bielen, Ken (2021). Portraying Performer Image in Record Album Cover Art (ebook ed.). Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-79364-073-4.

- ^ "Analysis of 1:34 of musique concrete by Spencer Dryden "A Small Package of Value Will Come to You, Shortly" Jefferson Airplane 1967 album AFTER BATHING AT BAXTER's". Mark Weber. January 12, 2019. Archived from the original on October 4, 2023. Retrieved November 11, 2024.

- ^ Kostanczuk, Bob (November 21, 2016). "Starship powered by long history of classic rock". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved November 11, 2024.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. "Yahoo! Music – Jefferson Airplane biography". Music.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on September 5, 2008. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ a b c Tamarkin 2003.

- ^ Fielder, Hugh (December 9, 2023). ""Grace was three sheets to the wind, so Marty sang to her while holding her in an arm-lock so she couldn't get away": the epic, drunken and very crazy story of Jefferson Starship". Louder. Archived from the original on November 13, 2024. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ The Doors: Live in Europe 1968. A*Vision Entertainment. 1991.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Adler, Renata (November 20, 1968). "In Which a Filmmaker Discovers the Evil City". The New York Times. p. 42.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, p. 197.

- ^ Allen, Gavin (November 18, 2009). "Paul Kantner talks Woodstock, Jefferson Starship and smashed cars". South Wales Echo. Archived from the original on October 13, 2012. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ The Dick Cavett Show: Rock Icons. Daphne Productions, Inc. 2005.

- ^ Gallucci, Michael (January 28, 2016). "Top 10 Jefferson Airplane Songs". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on May 17, 2021. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, pp. 194–195, 207.

- ^ Doggett, Peter (2007). There's A Riot Going On. Canongate. p. 287. OL 23092621M.

- ^ Harbron, Lucy (December 9, 2023). "What happened at the Altamont Free Festival?". Far Out Magazine. Archived from the original on November 11, 2024. Retrieved November 11, 2024.

- ^ Lydon, Michael (September 1970). "An Evening with the Grateful Dead". Rolling Stone.

- ^ "Interview: Paul Kantner". Music-Illumanati. April 25, 2010. Archived from the original on November 13, 2010. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ Manoucheri, David (December 7, 2023). "From the Archives: On Dec. 6, 1969, infamous 'free' concert at Altamont came to a tragic end". KCRA. Archived from the original on November 11, 2024. Retrieved November 11, 2024.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, pp. 211, 214–215.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, p. 216.

- ^ "Names In The News". Tri-City Herald. Kennewick, Washington. January 26, 1971. Retrieved December 5, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Daughter Born To Pop Singer". The Day. Vol. 90, no. 172. New London, Connecticut. January 26, 1971. p. 11. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, p. 239–240.

- ^ a b Planer, Lindsay. "Jefferson Airplane: Long John Silver Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on January 29, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2023.

- ^ Barron, Richard. "Rocker Johny Barbata remembers David Crosby". The Ada News. Ada, Oklahoma. Archived from the original on January 30, 2023. Retrieved February 5, 2023.

- ^ Snyder, Patrick (January 1, 1976). "Jefferson Starship: The Miracle Rockers". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 28, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ "Jefferson Airplane". Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ "The Core: Jefferson Airplane". Relix.com. Relix Media Group LLC. December 11, 2019. Archived from the original on December 18, 2019. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

Paul and I didn't know what was going on because Jack and Jorma took off to one of the Scandinavian countries to do some speed-skating. They didn't call back, and they were just gone. So Paul and I started making records as Jefferson Starship. We had to rename it because you couldn't call it Airplane unless all of the original members were making the record.

- ^ a b DeRiso, Nick (July 18, 2019). "Why Jefferson Airplane's Unexpected Reunion Crash Landed". Ultimate Classic Rock. Loudwire. Archived from the original on April 22, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

The original group had released a series of era-defining anti-establishment projects in the late '60s before morphing into Jefferson Starship, a far less political outfit.

- ^ Plantier, Boris (October 14, 2012). "Paul Kantner: The songs of Jefferson Airplane and Jefferson Starship are as relevant now as they were in the 60s". Yuzu Melodies. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

I wouldn't so much call Jefferson Starship a spinoff as, perhaps, an evolution.

- ^ Tamarkin 2003, p. 267.

- ^ "Jefferson Airplane - Jefferson Airplane". Discogs. November 15, 1989. Archived from the original on October 28, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ a b "Jefferson Airplane Accept 1996 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Awards". Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. January 11, 1996. Archived from the original on September 10, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2022 – via YouTube.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Jefferson Airplane Performs 'Volunteers' at the 1996 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Inductions". Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. January 11, 1996. Archived from the original on September 10, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2022 – via YouTube.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Hinckley, David (January 19, 1996). "This is Dedicated to the Women We Love From Shirelles to Gladys Knight, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Dinner Swells with the Feminine Mystique After Its Years of Guys with Guitars". Daily News. Archived from the original on January 19, 2018. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- ^ "Jorma & Jack Celebrate 50 Years of Jefferson Airplane". Lockn' Music Festival. March 20, 2015. Archived from the original on July 20, 2015. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ Platon, Adelle (January 13, 2016). "Run-D.M.C. to Receive Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 15, 2016. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ^ https://youtube.com/KZ2vFm35N7I[permanent dead link]

- ^ Kluft, Alex (October 14, 2022). "Jefferson Airplane Receive Hollywood Walk of Fame Star". Music Connection Magazine. Archived from the original on December 30, 2022. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ Arndt, Jaclyn (January 17, 2005). "Jefferson Airplane's Spencer Dryden Dies at 66". Soulshine. Archived from the original on March 22, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2016.

- ^ Kelly, Helen (February 1, 2016). "Jefferson Airplane's Signe Anderson dies aged 74 on same day as her bandmate Paul Kantner". Daily Express. Northern and Shell Media. Archived from the original on February 1, 2016. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

- ^ Greene, Andy (September 28, 2018). "Jefferson Airplane Co-Founder Marty Balin Dead at 76". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 30, 2018. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

Sources

[edit]- Butterworth, Richard (2021). Jefferson Airplane: every album, every song (on track ...). UK & US: Sonicbond Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78952-143-6.

- Fenton, Craig (2006). Take Me to a Circus Tent: The Jefferson Airplane Flight Manual. West Conshohocken, PA: Infinity Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7414-3656-6.

- Tamarkin, Jeff (2003). Got a Revolution!: The Turbulent Flight of Jefferson Airplane. New York, NY: Atria Books. ISBN 978-0-671-03403-0.

External links

[edit]- Jefferson Airplane at AllMusic

- FBI file on Jefferson Airplane

- Jefferson Airplane discography at MusicBrainz

- Jefferson Airplane

- 1965 establishments in California

- 1972 disestablishments in California

- 1965 in San Francisco

- American acid rock music groups

- CBS Records artists

- Epic Records artists

- Folk rock groups from California

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Musical groups established in 1965

- Musical groups disestablished in 1972

- Musical groups from San Francisco

- Musical groups reestablished in 1989

- Psychedelic rock music groups from California

- RCA Records artists

- RCA Victor artists

- Female-fronted musical groups

- American musical sextets

- Mixed-gender bands