Jim McDermott

Jim McDermott | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Washington's 7th district | |

| In office January 3, 1989 – January 3, 2017 | |

| Preceded by | Mike Lowry |

| Succeeded by | Pramila Jayapal |

| Chair of the House Ethics Committee | |

| In office January 3, 1993 – January 3, 1995 | |

| Preceded by | Louis Stokes |

| Succeeded by | Nancy Johnson |

| Member of the Washington Senate from the 43rd district | |

| In office January 13, 1975 – July 24, 1987 | |

| Preceded by | Jonathan Whetzel |

| Succeeded by | Janice Niemi |

| Member of the Washington House of Representatives from the 43rd district | |

| In office January 11, 1971 – January 8, 1973 | |

| Preceded by | Jonathan Whetzel |

| Succeeded by | Jeff Douthwaite |

| Personal details | |

| Born | James Adelbert McDermott December 28, 1936 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses | Virginia Beattie (div. 1989)Therese Hansen

(m. 1997; div. 2012) |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | Wheaton College (BS) University of Illinois, Chicago (MD) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1968–1970 |

| Rank | Lieutenant Commander |

| Unit | Medical Corps |

| Battles/wars | Vietnam War |

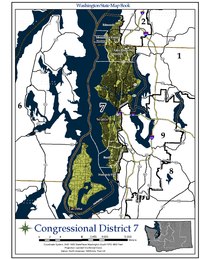

James Adelbert McDermott (born December 28, 1936) is an American politician and psychiatrist who was the U.S. representative for Washington's 7th congressional district from 1989 to 2017. He is a member of the Democratic Party. The 7th district includes most of Seattle, Vashon Island, Tukwila, Burien, Shoreline, Lake Forest Park, Lynnwood, Mountlake Terrace, Woodway, and Edmonds. He served on the House Ways and Means Committee and was a member of the House Progressive Caucus. He was formerly the committee chairman, then in 1995, ranking minority member on the House Ethics Committee. On January 4, 2016, he announced that he would not be seeking another congressional term.[1]

Early life, education, and early career

[edit]McDermott was born on December 28, 1936,[2] in Chicago, Illinois, the son of Roseanna (Wabel) and William McDermott.[3] He was the first member of his family to attend college;[4] he graduated from Wheaton College, Illinois, and then went to medical school, getting an M.D. from the University of Illinois College of Medicine in Chicago in 1963.[2] After completing an internship in 1964 at Buffalo General Hospital in Buffalo, New York, a two-year psychiatry residency at the University of Illinois Research and Educational Hospital (now called University of Illinois Research Hospital), and fellowship training in child psychiatry (1966–68) at the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle,[5] he served in the United States Navy Medical Corps as a psychiatrist in California during the Vietnam War.[4][6]

Early political career

[edit]

In 1970, McDermott made his first run for public office and was elected to the Washington state legislature as a representative from the 43rd District. He did not seek re-election in 1972 but instead ran for Governor of Washington losing the primary to former governor Albert Rosellini, who was seeking a return to the governorship after losing a third term bid in 1964.[7] Rosellini would lose that fall. In 1974, he ran for the state senate, and subsequently was re-elected three times, to three successive two-year terms.[8] During this time, he crafted and sponsored legislation that would eventually be called the Washington State Basic Health Plan, the first such state program in the country, which offers health insurance to the unemployed and the working poor.[9]

In 1980, while still a state senator, he saw a chance to take on incumbent governor Dixy Lee Ray in the Democratic primary for governor as she sought re-election. U.S. Senator Warren Magnuson endorsed McDermott and persuaded the leaders of the Washington State AFL–CIO to endorse and actively campaign for McDermott.[10] He was successful in the primary, upsetting an incumbent governor by a 57–42% landslide, but lost the general election to Republican John Spellman in the year of the Republican Ronald Reagan landslide. McDermott would lose 57–43% while Magnuson would lose in a narrow upset to Washington attorney general Slade Gorton.

McDermott chose for a third time in 1984 to run for governor. In his third gubernatorial campaign, he carried shiny red apples around the state as he campaigned in a state noted for its apple crops. He has pushed what he's called an "Apple agenda"—his acronym for Affordable health care, Promotion of jobs, Protection of the environment, Life with hope and without fear, and excellence in Education.[11] However, this time in the primary, he faced the Pierce County Executive Booth Gardner, a former state senator as well who ran in the slogan, "Booth Who?!" Gardner ran with a focus on LGBT and the pro-choice issues, and contributed $500,000 of his own funds to the campaign. McDermott ended up losing his third primary to Gardner, who then went on to defeat Spellman in the general election.[12]

In 1987, McDermott briefly left politics to become a Foreign Service medical officer based in Zaire (now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo), providing psychiatric services to Foreign Service, USAID, and Peace Corps personnel in sub-Saharan Africa.[citation needed]

U.S. House of Representatives

[edit]Elections

[edit]In 1988, the seat for Washington's 7th congressional district came open when five-term incumbent Mike Lowry gave it up to make an unsuccessful run for the Senate. McDermott returned from Africa to run for the seat and won handily with 71 percent of the vote. He was re-elected 13 times with no substantive opposition. He usually garnered wide support in his district, the most Democratic white-majority district in the nation, even in disastrous years for Democrats nationally. In 1994, for instance, he won with 75% of the vote even as the Republicans won control of Congress and took all but two seats in Washington (his and that of Norm Dicks). He was re-elected in 2010, taking 83 percent of the vote against independent challenger Bob Jeffers-Schroder. No Republican filed to contest the election in 2010.[13] In 2012 McDermott was challenged in the Democratic primary by attorney Andrew Hughes. Despite spending more than $200,000 on his campaign (versus McDermott's primary spending of $387,000), Hughes won just 6 percent of the vote to McDermott's 71 percent.[14] In the general election, McDermott won just under 80% of the vote, against Republican Ron Bemis.[15] McDermott did not seek reelection in 2016 following the announcement of a primary challenge by state representative Brady Walkinshaw.

Tenure

[edit]AIDS Housing Opportunity Act of 1990

[edit]In his first term, McDermott sponsored the AIDS Housing Opportunity Act, which provides state and local governments with the resources and incentives to devise long-term comprehensive strategies for meeting the housing needs of persons with AIDS and the families of such persons.[16]

The program established, known as HOPWA, has grown to be a $335M line in United States budget, at a cost of $5,432 per recipient in 2010. Despite the long-term focus of the original legislation, according to HUD, 59% of recipients received help with short-term housing.[17]

Cedar River Watershed Land Exchange Act of 1992

[edit]This consolidated land in Washington state which allowed the city of Seattle to gain greater control over its primary water source, thus enabling more efficient planning for the future. The bill was one of the last signed by President George H. W. Bush before he left office.[18]

2002 Iraq trip

[edit]In the fall of 2002, McDermott and fellow Representatives David Bonior of Michigan, Nick Rahall of West Virginia and Mike Thompson of California visited Iraq; in Baghdad they met with members of parliament and the Iraqi Foreign Minister, and in Basra they met with residents who talked about the effect on them of the Iraq sanctions. American conservatives sharply criticised McDermott for this trip, and for his predictions that President George W. Bush would "mislead the American public" to justify military action and that no WMD would be found in Iraq.[19]

After this trip, McDermott's opponents dubbed him "Baghdad Jim";[20][21] his supporters claimed that he had been proven correct on the facts.[22]

According to a disclosure form filed with the clerk of the House of Representatives, the nonprofit organization Life for Relief and Development paid McDermott's $5,510 travel expenses for the Iraq trip. On March 26, 2008, a Bush Administration indictment accused Muthanna Al-Hanooti of arranging for the trip and paying for it with funds from Saddam Hussein's intelligence agency, the IIS.[23] Ultimately these charges were dropped; Al-Hanooti was convicted of attempting to sell Iraqi oil to raise money for humanitarian purposes without permission of the U.S. Treasury.[24]

African Growth and Opportunity Act of 2004

[edit]This act lowered tariffs and spurred apparel trade with many African countries. The AGOA has brought approximately 15,000 jobs and $340 million in foreign investment to some of the poorest nations in sub-Saharan Africa.[25] On August 22, 2007, McDermott was knighted by King Letsie III of Lesotho, in recognition of McDermott's leadership on the Act.[26][27]

Violence Against Women and Justice Department Reauthorization Act of 2005

[edit]This piece of legislation strengthened privacy and confidentiality of people already receiving care under the Act and modernized it by prohibiting cyberstalking as defined under the law.[28]

Pledge of Allegiance

[edit]On April 28, 2004, Congressman McDermott omitted the phrase "under God" while leading the House in reciting the Pledge of Allegiance. The incident occurred after atheist Michael Newdow lost his court case to have the phrase "under God" dropped from the Pledge, and after McDermott had voted against a congressional resolution that called for overturning a court ruling that declared the phrase unconstitutional. In 1954, during the McCarthy era and communism scare, Congress had passed a bill, which was signed into law, to add the words "under God."[29] McDermott later stated that he had "reverted to the pledge as it was written and taught in the public schools throughout my childhood", as the phrase "under God" was added in 1954, the year in which McDermott graduated from high school;[30] he turned 18 in late December of that year, after graduating.[2]

Boehner v. McDermott

[edit]In December 2004, the House Ethics Committee investigated McDermott over the leaking of an illegally recorded telephone conversation during a 1997 committee investigation of then-Speaker Newt Gingrich.

In the conversation, Mr. Gingrich, his lawyer, and several other Republican Congressmen discussed how Gingrich's Congressional allies should deal with the political consequences of his admission that he had violated House ethics rules by giving inaccurate information to the House Ethics Committee for its inquiry into his use of tax-exempt funds. Democrats have described the conversation as evidence that Mr. Gingrich broke an agreement with the Ethics Committee that he would not orchestrate a politically motivated response to those committee findings.[31]

The recording was made by John and Alice Martin, who claimed that they had overheard the conversation on a police scanner, decided to record it for posterity's sake, and then decided that it might be important for the Ethics Committee to hear.[32] The Martins gave the tape to McDermott because he was the senior Democrat on the Ethics Committee.[33] Within two days, reportedly after the Republican Ethics Committee chair Nancy L. Johnson refused to allow a vote on making the tape part of the committee's records, sending the tape to the Justice Department, or taking any action against participants in the conversation,[34] and over the warning of the committee's counsel of possible legal liability, McDermott gave the tape to several media outlets, including the New York Times.

Rep. John Boehner, who was part of the Gingrich conversation, sued McDermott in his capacity as a private citizen, seeking punitive damages for violations of his First Amendment rights.[35] After U.S. District Judge Thomas Hogan ordered McDermott to pay Boehner for "willful and knowing misconduct" that "rises to the level of malice", McDermott appealed, arguing that since he had not created the recording, his actions were allowed under the First Amendment, and that ruling against him would have 'a huge chilling effect' on reporters and newsmakers alike. Eighteen news organizations – including ABC, NBC, CBS, CNN, The Associated Press, the New York Times and the Washington Post — filed a brief backing McDermott.[36] On March 29, 2006, the court ruled 2–1 that McDermott violated federal law when he turned over the illegally recorded tape to the media outlets, ordering McDermott to pay Boehner's legal costs (over $600,000) plus $60,000 in damages. On June 26, 2006, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit vacated the judgment, deciding to re-hear the case with all nine judges.[37] However, a split 4 to 1 to 4 en banc decision in Boehner v. McDermott, 484 F.3d 573 (D.C. Cir. 2007) affirmed the three-judge panel, but on different grounds;[38] the Supreme Court declined review.[39] [40] On March 31, 2008, Chief Judge Thomas Hogan of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia ordered McDermott to pay Boehner $1.05 million in attorney's fees, costs and interest. McDermott also paid over $60,000 in fines and close to $600,000 in his own legal fees.[41]

The Ethics Committee formally rebuked McDermott in 2006, writing he had "violated ethics rules by giving reporters access to an illegally taped telephone call involving Republican leaders a decade ago. Rep. McDermott's secretive disclosures to the news media ... risked undermining the ethics process" and that McDermott's actions "were not consistent with the spirit of the committee."[42] Previously, the Martins pleaded guilty to violating the Electronic Communications Privacy Act. In 1997, Gingrich was reprimanded by the House for providing false information to the Ethics Committee and he agreed to reimburse $300,000 in costs.

Depleted Uranium Study Act of 2006

[edit]This amendment to the Defense Authorization Act of 2006 directed the Department of Defense to study possible adverse health effects of the use of depleted uranium by the US military on servicemembers, employees and their families.[43]

Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008

[edit]A reform in the American foster care system, this legislation addresses needs affecting foster children in the United States; it extends federal foster care payments until children are 21 years old, provides federal support for relatives caring for foster children, increases access to foster care and adoption services by Native American tribes, and improves oversight of the health and education needs of children in foster care.[44]

Unemployment Compensation Extension Acts of 2008–2009

[edit]McDermott oversaw the emergency unemployment compensation extensions during the recession that began in 2008 under the George W. Bush administration and continued into the administration of Barack Obama.[45]

Ft. Lawton legislation

[edit]H.R. 3174 required the US Army Board for Correction of Military Records to review dozens of convictions that followed the Fort Lawton Riot of 1944. The Board uncovered "egregious error" in the prosecution, overturned the convictions, issued retroactive honorable discharges to the defendants and ordered back pay.[46] H.R. 5130 provided that such payments, which were otherwise of amounts considered nominal, to include interest.[47]

Worker, Home-ownership, and Business Assistance Act of 2009

[edit]The purpose of this act was to encourage job creation, strengthen the economic recovery, and assist those unable to find jobs during the serious economic downturn that began in 2008.[48] While the bill had unrelated provisions, the primary focus was on the extension of the $8,000 first-time home buyer tax credit; opinion is divided as to the effectiveness of the program.[49]

Conflict Minerals Trade Act of 2010

[edit]This legislation requires publicly traded companies in the United States exercise due diligence to ensure that conflict minerals (gold, tin, tantalum and tungsten) in their products do not come from mines funding civil war in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Originally proposed as a standalone bill, it became section 1502 of the 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. A United Nations Security Council committee reported that this legislation was a "catalyst" for efforts to save lives by cutting off a key source of funding for armed groups [50] at a cost to American firms of approximately $8 billion per year.[51]

Tax Parity for Health Plan Beneficiaries Act 2010, 2011

[edit]McDermott sponsored a bill which would have eliminated the tax burden incurred by married same sex couples, same-sex and opposite-sex domestic partners. The bill also would have ensured that domestic partners of federal civilian employees receive the same health care benefits as married spouses, including retirement, compensation for work injuries, and full life and health insurance benefits. It was eventually folded into and taken out of the House Health Care Bill in 2010, and has been referred to committee both times, where it died. Versions of this bill were co-sponsored under McDermott's leadership since the 106th Congress with Republican Senator Gordon Smith of Oregon. The 2010 (111th Congress) and 2011 (112th Congress) bills were co-sponsored by Democratic Senator Chuck Schumer of New York.[52]

The Internet Gambling Regulation and Tax Enforcement Act

[edit]In June 2011, McDermott introduced The Internet Gambling Regulation and Tax Enforcement Act (H.R. 2230) along with John Campbell (R-Calif.) and Barney Frank (D-Mass).[53] This represented McDermott's fifth introduction of such an act, which would offer a tax structure should online gambling become fully legalized and regulated within the United States.[54]

Committee assignments

[edit]

Formerly ranking majority leader, then, in 1995, as the minority member of the Ethics Committee after Republicans retook control of the House.

Caucus memberships

[edit]McDermott belonged to several dozen Congressional caucuses and co-chaired the following caucuses:

- Congressional HIV/AIDS Caucus

- Congressional Progressive Caucus

- Congressional Kidney Caucus

- Afterschool Caucuses[55]

Personal life

[edit]McDermott has been married twice. He and Virginia Beattie McDermott divorced in 1989. He married Therese Hansen in 1997, divorcing in 2012. In filings for his second divorce, McDermott's and Hansen's joint assets were valued at $2.5 million.[56] He has two children and three grandchildren.[57] McDermott maintains a home in Seattle, but has been living in Civrac-en-Médoc, near Bordeaux, France, where he vacationed in 2017 and bought a cottage "his second day in town" as vacation home and one hectare of a vineyard in a wine cooperative, a "potential refuge from a second Trump presidency".[58]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Brunner, Jim (January 4, 2016). "Jim McDermott to retire; many consider a run, including another McDermott". The Seattle Times. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- ^ a b c "McDERMOTT, James A. - Biographical Information". Bioguide.congress.gov. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ "James A. ("Jim") McDermott". Ancestry.com. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ a b "Biography". McDermott.house.gov. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ "Jim's Extended Biography". McDermott.house.gov. Archived from the original on December 5, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ Barber, Mike (October 8, 2006). "Sheehan offers refuge to war deserters". Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

- ^ "Our Campaigns - WA Governor - Blanket Primary Race - Sep 19, 1972".

- ^ "McDermott, Jim (B. 1936)".

- ^ "Medicare Commission". Medicare.commission.gov. December 28, 1936. Archived from the original on December 11, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- ^ "Gov. Dixy Lee Ray Gets a Spanking From Child Psychiatrist". The Washington Post. September 18, 1980.

- ^ "Two Democrats in Primary Fight to Face Washington's Governor". The New York Times. September 16, 1984.

- ^ "Gov. Booth Gardner, part-time islander, dies". March 19, 2013.

- ^ "November 02, 2010 General Election". Secretary of State of Washington. November 29, 2010. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

- ^ Gore, Mike (August 21, 2012). "Hughes Spends Over 6x More per Vote Than McDermott". The Stranger.

- ^ Reed, Sam. "WA 7th congressional election results". 2012 Election results. WA STATE SEC OF STATE. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012.

- ^ "Jim McDermott". Water 1st International. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ "HUD HOPWA Overview 2010". HUD Reviews HOPWA. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Archived from the original on May 2, 2011. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ^ Lilly, Dick (August 25, 1993). "Seattle Journal – Watershed's End Run Worked". The Seattle Times.

- ^ Postman, David (March 28, 2008). "The story behind McDermott's controversial Iraq trip". Seattle Times. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ "'Baghdad Jim' questions timing of capture". NBC News. December 16, 2003.

- ^ "Buzzing Over Baghdad Jim". Real Clear Politics. Archived from the original on April 18, 2009. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ Robert L. Jamieson, Jr., 'Baghdad Jim' was dead on about war, Seattle Post-Intelligencer, July 16, 2003. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ^ "Indictment: Hussein fed money to spy for U.S. officials' trip". CNN. March 26, 2008. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ^ "From spy to a patriot: Muthanna al-Hanooti". arabamericannews.com. January 10, 2009. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ "Resource on the African Growth and Opportunities Act". AGOA.info. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- ^ "McDermott knighted by king of Lesotho". Seattlepi.com. September 7, 2007. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ Congressman Jim McDermott – News – Rep. McDermott Knighted by King in Lesotho, South Africa Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "delawarefederallawyers.com". delawarefederallawyers.com. Archived from the original on July 9, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- ^ "Pledge of Allegiance and its "under God" phrase". Religioustolerance.org. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- ^ Buchanan, Wyatt (April 28, 2004). "McDermott's pledge error blamed on a childhood moment". Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

- ^ Lewis, Neil A. (January 16, 1997). "Inquiry on Gingrich Call to Look at Plausibility of Florida Couple's Account". New York Times. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- ^ "Potentially Illegal Gingrich Tape Turned Over To Criminal Investigators". CNN. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ Gray, Jerry (April 24, 1997). "Florida Couple Are Charged In Taping of Gingrich Call". New York Times. Retrieved June 28, 2011.

- ^ Gray, Jerry (January 15, 1997). "Democrat Quits Ethics Panel Over Leak of Gingrich Tape". New York Times. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ Alvarez, Lisette (January 15, 1997). "Congressman Sues a Colleague Over Disclosing G.O.P. Talks". New York Times. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ Daly, Matthew (March 28, 2006). "Appeals Court rules against McDermott in taped call dispute". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 30, 2006.

- ^ Daly, Matthew (June 26, 2006). "Court to Hear Arguments in Taped Call Case". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ ossma003 on (October 21, 2009). "CLA Publications: Full D.C. Circuit Rules McDermott Had No First Amendment Right to Leak Phone Tape Due to Ethics Committee Rules". Blog.lib.umn.edu. Archived from the original on June 8, 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ The Crypt's Blog – Politico.com

- ^ "Justices steer clear of lawmakers' feud". CNN. December 3, 2007. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ "Lawmaker Must Pay $1 Million in Legal Fees", Associated Press (International Herald Tribune), April 2, 2008.

- ^ Mundy, Alicia (December 12, 2006). "Ethics panel rebukes McDermott". The Seattle times. Archived from the original on September 7, 2008. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ "McDermott-Cantwell Depleted Uranium Study Amendment Passes Congress". Washblog. October 3, 2006. Archived from the original on September 19, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- ^ "Rep. McDermott's Foster Care Legislation Signed Into Law". Mcdermott.house.gov. October 8, 2008. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- ^ Jay Sumner (September 23, 2009). "Unemployment Compensation Extension Act : Washington D.C. Employment Law Update". Dcemploymentlawupdate.com. Archived from the original on March 29, 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- ^ Heather MacIntosh; Priscilla Long; David Wilma (July 6, 2005). "Riot involving African American soldiers occurs at Fort Lawton and an Italian POW is lynched on August 14, 1944". HistoryLink.org. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ^ "Ft. Lawton soldiers get back pay". Seattle Times. October 15, 2008. Archived from the original on October 19, 2008. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ^ Bill Summary & Status; 111th Congress (2009 - 2010); H.R.3548 at Congress.gov

- ^ KOCIENIEWSKI, David (April 26, 2010). "Mixed Results for Home Buyer Tax Credit". Home Buyer Tax Credit. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- ^ Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1533 (2004) concerning the Democratic Republic of the Congo (June 11, 2011). "Interim report of the Group of Experts on the DRC". United Nations. Archived from the original on January 26, 2012. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ National Association of Manufacturers. "Letter to Mary L. Shapiro" (PDF). Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- ^ Johnson, Chris (June 9, 2011). "McDermott introduces pro-gay tax equity bill". Washington Blade. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- ^ Kasperowicz, Pete (June 17, 2011). "House Internet gambling bill would require withholding taxes on winnings". The Hill. Retrieved January 3, 2011.

- ^ "McDermott bill to decriminalize online gaming". Livecasinodirect.com. April 6, 2010. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- ^ "Members". Afterschool Alliance. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ^ Brunner, Jim (August 14, 2012). "McDermott divorce goes to trial next week". The Seattle Times. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- ^ "Congressman Jim McDermott's Biography". U.S. House of Representatives. Archived from the original on April 13, 2010. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- ^ Becker, Elizabeth (February 27, 2024). "Why an ex-congressman is living in a 'safe house' from Trump". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Biography at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Financial information (federal office) at the Federal Election Commission

- Legislation sponsored at the Library of Congress

- Profile at Vote Smart

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Column archives at The Huffington Post

- Articles

- Congressman Jim McDermott advocates a Canadian-style system as a simple, cost-effective, humane alternative for the US, Fall 1994

- McDermott defends his patriotism, Charles Pope, Seattle Post-Intelligencer, October 3, 2002

- "U.S. Congressman Jim McDermott on the White House's 'Fear Factory'" – interview with McDermott, August 14, 2003

- Aide says McDermott wasn't aware of Saddam link, Jim Brunner, Seattle Times, April 17, 2004

- A War We Can Win by Rep. Jim McDermott, February 6, 2006

- McDermott backs Bush impeachment – Beren says impeachment effort is political ploy by Emily Heffter, Seattle Times, 9/10/08

- McDermott faces 5 challengers but no real re-election challenge by Emily Heffter, Seattle Times, 8/14/08

- 1936 births

- Living people

- Democratic Party Washington (state) state senators

- Democratic Party members of the Washington House of Representatives

- American psychiatrists

- American Episcopalians

- Politicians from Chicago

- Wheaton College (Illinois) alumni

- United States Navy Medical Corps officers

- University of Illinois College of Medicine alumni

- Military personnel from Illinois

- Military personnel from Seattle

- Physicians from Illinois

- Physicians from Washington (state)

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Washington (state)

- American expatriates in France

- 21st-century members of the United States House of Representatives

- 20th-century members of the Washington State Legislature