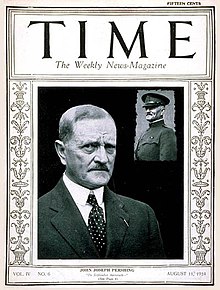

John J. Pershing

General of the Armies John J. Pershing | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | John Joseph Pershing |

| Nickname(s) | "Black Jack" |

| Born | September 13, 1860 near Laclede, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | July 15, 1948 (aged 87) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1882–1924 |

| Rank | General of the Armies |

| Service number | O-1 |

| Unit | Cavalry Branch |

| Commands | 8th Brigade[1][2] Mexican Expedition American Expeditionary Force First United States Army Chief of Staff of the United States Army |

| Battles / wars | See list |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Cross Distinguished Service Medal Silver Star Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (United Kingdom) Legion of Honour (France) |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 4, with Helen |

| Signature |  |

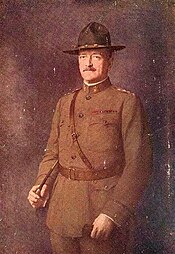

John Joseph Pershing GCB (September 13, 1860 – July 15, 1948),[a] nicknamed "Black Jack", was an American army general who served as the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) during World War I from 1917 to 1920. In addition to leading the AEF to victory in World War I, Pershing served as a mentor to many in the generation of generals who led the United States Army during World War II, including George C. Marshall, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Omar Bradley, Lesley J. McNair, George S. Patton, and Douglas MacArthur.[4][5]

During his command in World War I, Pershing resisted British and French demands that American forces be integrated with their armies, essentially as replacement units, and insisted that the AEF would operate as a single unit under his command, although some American units fought under British and Australian command, notably in the Battle of Hamel and the breaching of the Hindenburg Line at St Quentin Canal, precipitating the final German collapse. Pershing also allowed (at that time segregated) American all-Black units to be integrated with the French Army.

Pershing's soldiers first saw serious battle at Cantigny, Chateau-Thierry, and Belleau Wood on June 1–26, 1918, and Soissons on July 18–22, 1918. To speed up the arrival of American troops, they embarked for France leaving heavy equipment behind, and used British and French tanks, artillery, airplanes and other munitions. In September 1918 at St. Mihiel, the First Army was directly under Pershing's command; it overwhelmed the salient – the encroachment into Allied territory – that the German Army had held for three years. For the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, Pershing shifted roughly 600,000 American soldiers to the heavily defended forests of the Argonne, keeping his divisions engaged in hard fighting for 47 days, alongside the French. The Allied Hundred Days Offensive, of which the Argonne fighting was part, contributed to Germany calling for an armistice. Pershing was of the opinion that the war should continue and that all of Germany should be occupied in an effort to permanently destroy German militarism.

Pershing is the only American to be promoted in his own lifetime to General of the Armies, the highest possible rank in the United States Army.[b] Allowed to select his own insignia, Pershing chose to continue using four gold stars.[7]

Some of his tactics have been criticized both by other commanders at the time and by modern historians. His reliance on costly frontal assaults, long after other Allied armies had abandoned such tactics, has been blamed for causing unnecessarily high American casualties.[8]

Pershing was also criticized by some historians for his actions on the day of armistice as the commander of the American Expeditionary Force. Pershing did not approve of the armistice, and despite knowing of the imminent ceasefire, he did not tell his commanders to suspend any new offensive actions or assaults in the final few hours of the war.[9] In total, there were nearly 11,000 casualties (3,500 American), dead, missing, or injured during November 11, the final day of the war, which exceeded the D-Day casualty counts of June 1944. For instance, allied casualties on the first day of the D-Day invasion were 4,414 confirmed dead.[10]

Pershing and several subordinates were later questioned by Congress;[9] Pershing maintained that he had followed the orders of his superior, Ferdinand Foch; Congress found that no one was culpable.[11]

Early life

[edit]Pershing was born on a farm near Laclede, Missouri, on September 13, 1860,[12] the son of farmer and store owner John Fletcher Pershing and homemaker Ann Elizabeth Thompson.[13] Pershing's great-grandfather, Frederick Pfoerschin emigrated from Alsace and arrived in Philadelphia in 1749.[14] He had five siblings who lived to adulthood: brothers James F. (1862–1933) and Ward (1874–1909), and sisters Mary Elizabeth (1864–1928), Anna May (1867–1955) and Grace (1867–1903); three other children died in infancy.[15][16] When the Civil War began, his father supported the Union and was a sutler for the 18th Missouri Volunteer Infantry; he died on March 16, 1906.[17] Pershing's mother died during his initial assignment in the American West.[17]

Pershing attended a school in Laclede that was reserved for precocious students who were also the children of prominent citizens, and he later attended Laclede's one-room schoolhouse.[10] After completing high school in 1878, he became a teacher of local African American children.[10] While pursuing his teaching career, Pershing also studied at the State Normal School (now Truman State University) in Kirksville, Missouri, from which he graduated in 1880 with a Bachelor of Science degree in scientific didactics.[18][19] Two years later, he competed for appointment to the United States Military Academy.[20] He performed well on the examination, and received the appointment from Congressman Joseph Henry Burrows.[21] He later admitted that he had applied not because he was interested in a military career, but because the education was free and better than what he could obtain in rural Missouri.[20]

West Point years

[edit]

Pershing was sworn in as a West Point cadet in July 1882.[22] He was selected early for leadership positions and became successively First Corporal, First Sergeant, First Lieutenant, and First Captain, the highest possible cadet rank.[23] Pershing also commanded, ex officio, the honor guard that saluted the funeral train of President Ulysses S. Grant as it passed West Point in August 1885.[24]

Pershing graduated in the summer of 1886 ranked 30th in his class of 77, and was commissioned a second lieutenant;[25] he was commended by the West Point Superintendent, General Wesley Merritt, who said Pershing gave early promise of becoming an outstanding officer.[26] Pershing briefly considered petitioning the Army to let him study law and delay the start of his mandatory military service.[27] He also considered joining several classmates in a partnership that would pursue development of an irrigation project in Oregon.[28] He ultimately decided against both courses of action in favor of active Army duty.[29]

Early career

[edit]Pershing reported for active duty on September 30, 1887, and was assigned to Troop L of the 6th U.S. Cavalry stationed at Fort Bayard, in the New Mexico Territory. While serving in the 6th Cavalry, Pershing participated in several Indian campaigns and was cited for bravery for actions against the Apache. During his time at Fort Stanton, Pershing and close friends Lt. Julius A. Penn and Lt. Richard B. Paddock were nicknamed "The Three Green P's," spending their leisure time hunting and attending Hispanic dances. Pershing's sister Grace married Paddock in 1890.[30]

Between 1887 and 1890, Pershing served with the 6th Cavalry at various postings in New Mexico, Arizona, and South Dakota.[31] He also became an expert marksman and won several prizes for rifle and pistol at army shooting competitions.[32]

On December 9, 1890, Pershing and the 6th Cavalry arrived at Fort Meade, South Dakota where Pershing played a role in suppressing the last uprisings of the Lakota (Sioux) Indians.[33][34] Though he and his unit did not participate in the Wounded Knee Massacre, they did fight three days after it on January 1, 1891, when Sioux warriors attacked the 6th Cavalry's supply wagons.[35] When the Sioux began firing at the wagons, Pershing and his troops heard the shots, and rode more than six miles to the location of the attack.[35] The cavalry fired at the forces of Chief War Eagle, causing them to retreat.[35] This was the only occasion on which Pershing saw action during the Ghost Dance campaign.[35]

In September 1891, he was assigned as the professor of military science and tactics at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, a position he held until 1895. While carrying out this assignment, Pershing attended the university's College of Law,[36] from which he received his LL.B. degree in 1893.[37] He formed a drill company of chosen university cadets, Company A. In March 1892, it won the Maiden Prize competition of the National Competitive Drills in Omaha, Nebraska. The Citizens of Omaha presented the company with a large silver cup, the "Omaha Cup". On October 2, 1894, former members of Company A established a fraternal military drill organization named the Varsity Rifles. The group renamed itself the Pershing Rifles in 1895 in honor of its mentor and patron.[38] Pershing maintained a close relationship with Pershing Rifles for the remainder of his life.[39][40]

On October 20, 1892,[41] Pershing was promoted to first lieutenant and in 1895 took command of a troop of the 10th Cavalry Regiment, one of the original Buffalo Soldier regiments composed of African-American soldiers under white officers. From Fort Assinniboine in north central Montana, he commanded an expedition to the south and southwest that rounded up and deported a large number of Cree Indians to Canada.

West Point instructor

[edit]

In 1897, Pershing was appointed to the West Point tactical staff as an instructor, where he was assigned to Cadet Company A. Because of his strictness and rigidity, Pershing was unpopular with the cadets, who took to calling him "Nigger Jack" because of his service with the 10th Cavalry.[42][43][44]

During the course of his tour at the Academy, this epithet softened to "Black Jack," although, according to Vandiver, "the intent remained hostile."[45] Still, this nickname stuck with Pershing for the rest of his life, and was known to the public as early as 1917.[46]

Spanish– and Philippine–American wars

[edit]At the start of the Spanish–American War, First Lieutenant Pershing was the regimental quartermaster for the 10th Cavalry. His duties as quartermaster had him unloading supplies at Daiquiri Cuba on 24 June. He missed the Battle of Las Guasimas that was fought that same day but arrived at the battle site late in the afternoon of 24 June. He fought on Kettle and San Juan Hills in Cuba, and was cited for gallantry. Theodore Roosevelt, who also participated in those battles, said that "Captain Pershing is the coolest man under fire I ever saw in my life.”[47] In 1919, Pershing was awarded the Silver Citation Star for these actions, and in 1932 the award was upgraded to the Silver Star decoration. A commanding officer here commented on Pershing's calm demeanor under fire, saying he was "cool as a bowl of cracked ice."[48] Pershing also served with the 10th Cavalry during the siege and surrender of Santiago de Cuba.[49]

Pershing was commissioned as a major of United States Volunteers on August 26, 1898, and assigned as an ordnance officer. In March 1899, after suffering from malaria, Pershing was put in charge of the Office of Customs and Insular Affairs which oversaw occupation forces in territories gained in the Spanish–American War, including Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam. He was honorably discharged from the volunteers and reverted to his permanent rank of first lieutenant on May 12, 1899. He was again commissioned as a major of Volunteers on June 6, 1899, this time as an assistant adjutant.

When the Philippine–American War began, Pershing reported to Manila on August 17, 1899, was assigned to the Department of Mindanao and Jolo, and commanded efforts to suppress the Filipino Insurrection.[50] On November 27, 1900, Pershing was appointed adjutant general of his department and served in this posting until March 1, 1901. He was cited for bravery for actions on the Cagayan River while attempting to destroy a Philippine stronghold at Macajambo.

Pershing wrote in his autobiography that "The bodies [of some Moro outlaws] were publicly buried in the same grave with a dead pig."[51][52] This treatment was used against captured juramentado so that the superstitious Moro would believe they would be going to hell.[53] Pershing added that "it was not pleasant [for the Army] to have to take such measures".[51][54] Historians do not believe that Pershing was directly involved with such incidents, or that he personally gave such orders to his subordinates. Letters and memoirs from soldiers describing events similar to this do not have credible evidence of Pershing having been personally involved.[55][56] Military historian B.H. Liddell Hart wrote that, on the contrary, Pershing's conduct toward the Moros was notable for its "unexpected sympathy," and for the fact that, because of Pershing's conscious effort to interact with and understand them, "he could negotiate with the Moros without the intervention of an interpreter."[57]

On June 30, 1901, Pershing was honorably discharged from the Volunteers and he reverted to the rank of captain in the Regular Army, to which he had been promoted on February 2, 1901. He served with the 1st Cavalry Regiment in the Philippines. He later was assigned to the 15th Cavalry Regiment, serving as an intelligence officer and participating in actions against the Moros. He was cited for bravery at Lake Lanao. In June 1901, he served as commander of Camp Vicars in Lanao, Philippines, after the previous camp commander was promoted to brigadier general.[58]

Rise to general

[edit]In June 1903, Pershing was ordered to return to the United States. President Theodore Roosevelt, taken by Pershing's ability, petitioned the Army General Staff to promote Pershing to colonel. At the time, Army officer promotions were based primarily on seniority rather than merit,[48] and although there was widespread acknowledgment that Pershing should serve as a colonel, the Army General Staff declined to change their seniority-based promotion tradition just to accommodate Pershing. They would not consider a promotion to lieutenant colonel or even major. This angered Roosevelt, but since the President could only name and promote army officers in the generals' ranks, his options for recognizing Pershing through promotion were limited.

In 1904, Pershing was assigned as the Assistant Chief of Staff of the Southwest Army Division stationed at Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. In October 1904, he began attendance at the Army War College,[59] and then was ordered to Washington, D.C., for "general duties unassigned."

Since Roosevelt could not yet promote Pershing, he petitioned the United States Congress to authorize a diplomatic posting, and Pershing was stationed as military attaché in Tokyo after his January 1905 War College graduation. Also in 1905, Pershing married Helen Frances Warren, the daughter of powerful U.S. Senator Francis E. Warren, a Wyoming Republican who served at different times as chairman of the Military Affairs and Appropriations Committees. This union with the daughter of a powerful politician who had also received the Medal of Honor during the American Civil War continued to aid Pershing's career even after his wife died in 1915.[60]

After serving as an observer in the Russo-Japanese War attached to General Kuroki Tamemoto's Japanese First Army in Manchuria from March to September,[61] Pershing returned to the United States in the fall of 1905. President Roosevelt employed his presidential prerogative and nominated Pershing as a brigadier general, a move of which Congress approved. In skipping three ranks and more than 835 officers senior to him, the promotion gave rise to accusations that Pershing's appointment was the result of political connections and not military abilities.[62] However, several other junior officers were similarly advanced to brigadier general ahead of their peers and seniors, including Albert L. Mills (captain), Tasker H. Bliss (major), and Leonard Wood (captain). Pershing's promotion, while unusual, was not unprecedented, and had the support of many soldiers who admired his abilities.[63][64]

In 1908, Pershing briefly served as a U.S. military observer in the Balkans, an assignment which was based in Paris. Upon returning to the United States at the end of 1909, Pershing was assigned once again to the Philippines, an assignment in which he served until 1913. While in the Philippines, he served as Commander of Fort McKinley, near Manila, and also was the governor of the Moro Province. The last of Pershing's four children was born in the Philippines, and during this time he became an Episcopalian.

In 1913, Pershing was recommended for the Medal of Honor following his actions at the Battle of Bud Bagsak.[65] He wrote to the Adjutant General to request that the recommendation not be acted on, though the board which considered the recommendation had already voted no before receiving Pershing's letter.[66] In 1922 a further review of this event resulted in Pershing being recommended for the Distinguished Service Cross, but as the Army Chief of Staff Pershing disapproved the action.[67] In 1940 Pershing received the Distinguished Service Cross for his heroism at Bud Bagsak, with President Franklin D. Roosevelt presenting it in a ceremony timed to coincide with Pershing's 80th birthday.[68]

During this period Pershing's reputation for both stern discipline and effective leadership continued to grow, with one experienced old soldier under his command later saying Pershing was an "S.O.B." and that he hated Pershing's guts, but that "as a soldier, the ones then and the ones now couldn't polish his (Pershing's) boots."[69]

Pancho Villa and Mexico

[edit]

On December 20, 1913, Pershing received orders to take command of the 8th Brigade at the Presidio in San Francisco. With tensions running high on the border between the United States and Mexico because of the Mexican Revolution, the brigade was deployed to Fort Bliss, Texas, on April 24, 1914, arriving there on the 27th.[70]

Death of wife Frances and daughters

[edit]After a year at Fort Bliss, Pershing decided to take his family there. The arrangements were almost complete, when on the morning of August 27, 1915, he received a telegram informing him of a house fire at the Presidio in San Francisco, where a lacquered floor ignited; the flames rapidly spread, resulting in the smoke inhalation deaths of his wife, Frances Warren Pershing and three young daughters: Mary Margaret, age 3; Anne Orr, age 7; and Helen, age 8. Only his 6-year-old son, Warren, survived.[71][72] After the funerals at Lakeview Cemetery in Cheyenne, Wyoming, Pershing returned to Fort Bliss with his son, Warren, and his sister, May, and resumed his duties as commanding officer.[73][74]

Commander of Villa expedition

[edit]

On March 15, 1916,[75][76][77] Pershing led an expedition into Mexico to capture Pancho Villa. This expedition was ill-equipped and hampered by a lack of supplies due to the breakdown of the Quartermaster Corps. Although there had been talk of war on the border for years, no steps had been taken to provide for the handling of supplies for an expedition. Despite this and other hindrances, such as the lack of aid from the former Mexican government, and their refusal to allow American troops to transport troops and supplies over their railroads, Pershing organized and commanded the Mexican Punitive Expedition, a combined armed force of 10,000 men that penetrated 350 miles (560 km) into chaotic Mexico. They routed Villa's revolutionaries, but failed to capture him.[78][79]

World War I

[edit]

At the start of the United States' involvement in World War I, President Woodrow Wilson considered mobilizing an army to join the fight. Frederick Funston, Pershing's superior in Mexico, was being considered for the top billet as the Commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) when he died suddenly from a heart attack on February 19, 1917. Pershing was the most likely candidate other than Funston, and following America's entrance into the war in May, Wilson briefly interviewed Pershing, and then selected him for the command. He was officially installed in the position on May 10, 1917, and held the post until 1918. Pershing chose Chaumont, France as the AEF headquarters. On October 6, 1917, Pershing, then a major general, was promoted to full general in the National Army. He bypassed the three star rank of lieutenant general, and was the first full general since Philip Sheridan in 1888.

As AEF commander, Pershing was responsible for the organization, training, and supply of a combined professional and draft Army and National Guard force that eventually grew from 27,000 inexperienced men to two field armies, with a third forming as the war ended, totaling over two million soldiers. Pershing was keenly aware of logistics, and worked closely with AEF's Services of Supply (SOS). The new agency performed poorly under generals Richard M. Blatchford and Francis Joseph Kernan; finally in 1918 James Harbord took control and got the job done.[80] Pershing also worked with Colonel Charles G. Dawes—whom he had befriended in Nebraska and who had convinced him not to give up the army for a legal career—to establish an Interallied coordination Board, the Military Board of Allied Supply.[81][82]

Pershing exercised significant control over his command, with a full delegation of authority from Wilson and Secretary of War Newton D. Baker. Baker, cognizant of the endless problems of domestic and allied political involvement in military decision making in wartime, gave Pershing unmatched authority to run his command as he saw fit. In turn, Pershing exercised his prerogative carefully, not engaging in politics or disputes over government policy that might distract him from his military mission. While earlier a champion of the African-American soldier, he did not advocate their full participation on the battlefield, understanding the general racial attitudes of white Americans.

George C. Marshall served as one of Pershing's top assistants during and after the war. Pershing's initial chief of staff was James Harbord, who later took a combat command but worked as Pershing's closest assistant for many years and remained extremely loyal to him.

After departing from Fort Jay at Governors Island in New York Harbor under top secrecy on May 28, 1917, aboard the RMS Baltic, Pershing arrived in France in June 1917.[83] In a show of American presence, part of the 16th Infantry Regiment marched through Paris shortly after his arrival. Pausing at the tomb of Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, he was reputed to have uttered the famous line "Lafayette, we are here," a line spoken, in fact, by his aide, Colonel Charles E. Stanton.[84] American forces were deployed in France in the autumn of 1917.

In September 1917, the French government commissioned a portrait of Pershing by 23-year-old Romanian artist Micheline Resco. Pershing removed the stars and flag from his car and sat up front with his chauffeur while traveling from his AEF headquarters to visit her by night in her apartment on the rue Descombes. Their friendship continued for the rest of his life.[85] In 1946, at 85, Pershing secretly wed Resco in his Walter Reed Hospital apartment. Resco was 35 years his junior[86]

Battle of Hamel

[edit]

For the first time in American history, Pershing allowed American soldiers to be under the command of a foreign power. In late June, General Sir Henry Rawlinson, commanding the British Fourth Army, suggested to Australian Lieutenant General John Monash that American involvement in a set-piece attack alongside the experienced Australians in the upcoming Battle of Hamel would both give the American troops experience and also strengthen the Australian battalions by an additional company each. On June 29, Major General George Bell Jr., commanding the American 33rd Division, selected two companies each from the 131st and 132nd Infantry Regiments of the 66th Brigade. Monash had been promised ten companies of American troops and on June 30 the remaining companies of the 1st and 2nd battalions of the 131st regiment were sent. Each American platoon was attached to a First Australian Imperial Force company, but there was difficulty in integrating the American platoons (which numbered 60 men) among the Australian companies of 100 men. This difficulty was overcome by reducing the size of each American platoon by one-fifth and sending the troops thus removed, which numbered 50 officers and men, back to battalion reinforcement camps.

The day before the attack was scheduled to commence, Pershing learned of the plan and ordered the withdrawal of six American companies.[87] While a few Americans, such as those attached to the 42nd Battalion, disobeyed the order, the majority, although disappointed, moved back to the rear. This meant that battalions had to rearrange their attack formations and caused a serious reduction in the size of the Allied force. For example, the 11th Brigade was now attacking with 2,200 men instead of 3,000.[88] There was a further last-minute call for the removal of all American troops from the attack, but Monash, who had chosen July 4 as the date of the attack out of "deference" to the US troops, protested to Rawlinson and received support from Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, commander of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF).[87][88] The four American companies that had joined the Australians during the assault were withdrawn from the line after the battle and returned to their regiments, having gained valuable experience. Monash sent the 33rd Division's commander, Bell, his personal thanks, praising the Americans' gallantry, while Pershing set out explicit instructions to ensure that US troops would not be employed in a similar manner again (except as described below).[87]

African American units

[edit]Under civilian control of the military, Pershing adhered to the racial policies of President Woodrow Wilson, Secretary of War Newton D. Baker, and southern Democrats who promoted the "separate but equal" doctrine. African-American "Buffalo Soldiers" units were not allowed to participate with the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) during the war, but experienced non-commissioned officers were provided to other segregated black units for combat service – such as the 317th Engineer Battalion.[89] The American Buffalo Soldiers of the 92nd and 93rd Infantry Divisions were the first American soldiers to fight in France in 1918, but they did so under French command as Pershing had detached them from the AEF to get them into action. Most regiments of the 92nd and all of the 93rd would continue to fight under French command for the duration of the war.[90]

Full American participation

[edit]Organization

[edit]

When General Pershing met General Pétain at Compiègne at 10:45pm on the evening of March 25, 1918, Pétain told him he had few reserves left to stop the German Spring Offensive on the Western Front. In response, Pershing said he would waive the idea of forming a separate American I Corps, and put all available American divisions at Pétain's disposal.[91][92] The message was repeated to General Foch on March 28, after Foch assumed command of all allied armies.[93] Most of these divisions were sent south to relieve French divisions, which were transported to the fight in Flanders.

By early 1918, entire divisions were beginning to serve on the front lines alongside French troops. Although Pershing desired that the AEF fight as units under American command rather than being split up by battalions to augment British and French regiments and brigades, the 27th and 30th Divisions, grouped under II Corps command, were loaned during the desperate days of spring 1918, and fought with the British Fourth Army under General Rawlinson until the end of the war, taking part in the breach of the Hindenburg Line in October.

By May 1918, Pershing had become discontented with Air Service of the American Expeditionary Force, believing staff planning had been inefficient with considerable internal dissension, as well as conflict between its members and those of Pershing's General Staff. Further, aircraft and unit totals lagged far behind those expected. Pershing appointed his former West Point classmate and non-aviator, Major General Mason Patrick as the new Chief of Air Service. Considerable house-cleaning of the existing staff resulted from Patrick's appointment, bringing in experienced staff officers to administrate, and tightening up lines of communication.[94][95]

In October 1918, Pershing saw the need for a dedicated Military Police Corps and the first U.S. Army MP School was established at Autun, France. For this, he is considered the founding father of the United States MPs.[96]

Because of the effects of trench warfare on soldiers' feet, in January 1918, Pershing oversaw the creation of an improved combat boot, the "1918 Trench Boot," which became known as the "Pershing Boot" upon its introduction.[97]

Combat

[edit]

American forces first saw serious action during the summer of 1918, contributing eight large divisions, alongside 24 French ones, at the Second Battle of the Marne. Along with the British Fourth Army's victory at Amiens on August 8, the Allied victory at the Second Battle of the Marne marked the turning point of World War I on the Western Front.

In August 1918 the U.S. First Army had been formed, first under Pershing's direct command (while still in command of the AEF) and then by Lieutenant General Hunter Liggett, when the U.S. Second Army under Lieutenant General Robert Bullard was created in mid-October. After a relatively quick victory at Saint-Mihiel, east of Verdun, some of the more bullish AEF commanders had hoped to push on eastwards to Metz, but this did not fit in with the plans of the Allied Supreme Commander, Marshal Ferdinand Foch, for three simultaneous offensives into the "bulge" of the Western Front (the other two being the French Fourth Army's breach of the Hindenburg Line and an Anglo-Belgian offensive, led by General Sir Herbert Plumer's British Second Army, in Flanders). Instead, the AEF was required to redeploy and aided by French tanks, launched a major offensive northward in very difficult terrain at Meuse-Argonne. Initially enjoying numerical odds of eight to one, this offensive eventually engaged 35 or 40 of the 190 or so German divisions on the Western Front, although to put this in perspective, around half the German divisions were engaged on the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) sector at the time.

The offensive was marked by a Pershing failure, specifically his reliance on massed infantry attacks with little artillery support led to high casualty rates in the capturing of three key points. This was despite the AEF facing only second-line German troops after the decision by Erich Ludendorff, the German Chief of Staff, to withdraw to the Hindenburg Line on October 3 – and in notable contrast to the simultaneous British breakthrough of the Hindenburg Line in the north. Pershing was subsequently forced to reorganize the AEF with the creation of the Second Army, and to step down as the commander of the First Army.[98]

When he arrived in Europe, Pershing had openly scorned the slow trench warfare of the previous three years on the Western Front, believing that American soldiers' skill with the rifle would enable them to avoid costly and senseless fighting over a small area of no-man's land. This was regarded as unrealistic by British and French commanders, and (privately) by a number of Americans such as the former Army Chief of Staff General Tasker Bliss and even Liggett. Even German generals were negative, with Erich Ludendorff dismissing Pershing's strategic efforts in the Meuse-Argonne offensive by recalling how "the attacks of the youthful American troops broke down with the heaviest losses".[99] The AEF had performed well in the relatively open warfare of the Second Battle of the Marne, but the eventual American casualties against German defensive positions in the Argonne (roughly 120,000 American casualties in six weeks, against 35 or 40 German divisions) were not noticeably better than those of the Franco-British offensive on the Somme two years earlier (600,000 casualties in four and a half months, versus 50 or so German divisions). More ground was gained, but by this stage of the war the German Army was in worse shape than in previous years.

Some writers[100] have speculated that Pershing's frustration at the slow progress through the Argonne was the cause of two incidents which then ensued. First, he ordered the U.S. First Army to take "the honor" of recapturing Sedan, site of the French defeat in 1870; the ensuing confusion (an order was issued that "boundaries were not to be considered binding") exposed American troops to danger not only from the French on their left, but even from one another, as the 1st Division tacked westward by night across the path of the 42nd Division (accounts differ as to whether Brigadier General Douglas MacArthur, then commanding the 84th Brigade of the 42nd Division, was really mistaken for a German officer and arrested).[101] Liggett, who had been away from headquarters the previous day, had to sort out the mess and implement the instructions from the Allied Supreme Command, Marshal Foch, allowing the French to recapture the city; he later recorded that this was the only time during the war in which he lost his temper, describing the event as "an atrocity".[102]

Second, Pershing sent an unsolicited letter to the Allied Supreme War Council, demanding that the Germans not be given an armistice and that instead, the Allies should push on and obtain an unconditional surrender.[103] Although in later years, many, including President Franklin D. Roosevelt, felt that Pershing had been correct, at the time, this was a breach of political authority. Pershing narrowly escaped a serious reprimand from Wilson's aide, "Colonel" Edward M. House, and later apologized.[104]

At the time of the Armistice with Germany, another Franco-American offensive was due to start on November 14, thrusting towards Metz and into Lorraine, to take place simultaneously with further BEF advances through Belgium. In his memoirs, Pershing claimed that the American breakout from the Argonne at the start of November was the decisive event leading to the German acceptance of an armistice, because it made untenable the Antwerp–Meuse line. This is probably an exaggeration; the outbreak of civil unrest and naval mutiny in Germany, the collapse of Bulgaria, the Ottoman Empire, and particularly Austria-Hungary following Allied victories in Salonika, Syria, and Italy, and the Allied victories on the Western Front were among a series of events in the autumn of 1918 which made it clear that Allied victory was inevitable, and diplomatic inquiries about an armistice had been going on throughout October.

President Wilson was keen to tie matters up before the mid-term elections,[citation needed] and as the other Allies were running low on supplies and manpower,[105] they followed Wilson's lead.[citation needed]

American successes were largely credited to Pershing, and he became the most celebrated American leader of the war. MacArthur, however, saw Pershing as a desk soldier, and the relationship between the two men deteriorated by the end of the war. Similar criticism of senior commanders by the younger generation of officers (the future generals of World War II) was made in the British and other armies, but, in Pershing's defense, although it was not uncommon for brigade commanders to serve near the front and even be killed, the state of communications in World War I made it more practical for senior generals to command from the rear.

He controversially ordered the First and Second Armies to continue fighting before the signed Armistice took effect. This resulted in 3,500 American casualties on the last day of the war, an act which was regarded as murder by a few officers under his command. Pershing doubted the Germans' good faith, and most of his contemporaries took the view he expressed to the House Committee on Military Affairs in his testimony on November 5, 1919:

When the subject of the armistice was under discussion we did not know what the purpose of it was definitely, whether it was something proposed by the German High Command to gain time or whether they were sincere in their desire to have an armistice; and the mere discussion of an armistice would not be sufficient grounds for any judicious commander to relax his military activities....No one could possibly know when the armistice was to be signed, or what hour be fixed for the cessation of hostilities so that the only thing for us to do, and which I did as commander in chief of the American forces, and which Marshal Foch did as commander in chief of the Allied armies was to continue the military activities....[11]

The year of 1918 also saw a personal health struggle for Pershing as he was sickened during the 1918 flu pandemic, but unlike many who were not so fortunate, Pershing survived.[106] He rode his horse, Kidron, in the Paris victory parade in 1919.[107]

Later career

[edit]

In September 1919, in recognition of his distinguished service during World War I, the U.S. Congress authorized the President to promote Pershing to General of the Armies of the United States, the highest rank possible for any member of the United States armed forces, which was created especially for him.[108]

In 1976, Congress authorized President Gerald Ford to posthumously promote George Washington to this rank as part of the United States Bicentennial; Washington previously held the rank of General in the Continental Army, and wore a three-star insignia;[109] his posthumous appointment to General of the Armies rank and the specific wording of the authorizing statute, Public Law 94-479,[110] of October 1976, ensured that Washington would always be considered the U.S. Army's highest-ranking officer.[111][112] Pershing was authorized to create his insignia for the new rank and chose to continue wearing four silver stars[113][114][115] for the rest of his career.[116]

In 1919, Pershing created the Military Order of the World War as an officer's fraternity for veterans of the First World War, modeled after the Military Order of Foreign Wars. Both organizations still exist today and welcome new officer members to their ranks. Pershing himself would join the MOFW in 1924.

There was a movement to draft Pershing as a candidate for president in 1920; he refused to campaign, but indicated that he "wouldn't decline to serve" if the people wanted him.[117] Though Pershing was a Republican, many of his party's leaders considered him too closely tied to the policies of the Democratic Party's President Woodrow Wilson.[118] Another general, Leonard Wood, was the early Republican front runner, but the nomination went to Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio, who went on to win the general election.[119]

In 1921, Pershing became Chief of Staff of the United States Army, serving for three years. He created the Pershing Map, a proposed national network of military and civilian highways. The Interstate Highway System instituted in 1956 bears considerable resemblance to the Pershing map. On his 64th birthday, September 13, 1924, Pershing retired from active military service. (Army regulations from the late 1860s to the early 1940s required officers to retire on their 64th birthday.)

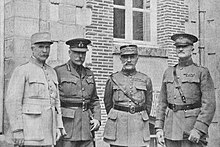

On November 1, 1921, Pershing was in Kansas City to take part in the groundbreaking ceremony for the Liberty Memorial that was being constructed there, (now known as the National World War I Museum and Memorial). Also present that day were Lieutenant General Baron Jacques of the Belgian Army, Admiral of the Fleet David Beatty of the British Royal Navy, Marshal Ferdinand Foch of the French Army, and General Armando Diaz of the Royal Italian Army. One of the main speakers was Vice President Calvin Coolidge. In 1935, bas-reliefs of Pershing, Jacques, Foch and Diaz by sculptor Walker Hancock were added to the memorial. Pershing also laid the cornerstone of the World War Memorial in Indianapolis on July 4, 1927.[120]

On October 2, 1922, amid several hundred officers, many of them combat veterans of World War I, Pershing formally established the Reserve Officers Association (ROA) as an organization at the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C. ROA is a 75,000-member, professional association of officers, former officers, and spouses of all the uniformed services of the United States, primarily the Reserve and United States National Guard. It is a congressionally chartered Association that advises the Congress and the President on issues of national security on behalf of all members of the Reserve Component.

In 1924, Pershing became a member of the Pennsylvania Society of the Sons of the American Revolution. He was also an honorary member of the Society of the Cincinnati and a Veteran Companion of the Military Order of Foreign Wars. On January 5, 1935, Pershing was designated a Military Order of the World Wars Honorary Commander-in-Chief for Life.[121]

Pershing served on a committee of the Sons of the American Revolution to establish and recognize Constitution Day in the United States.[122]

During the 1930s, Pershing largely retreated to private life, but returned to the public eye with publication of his memoirs, My Experiences in the World War, which were awarded the 1932 Pulitzer Prize for history. He was also an active Civitan during this time.[123]

In 1937, Pershing created a custom full dress uniform to attend the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, denoting his rank with four gold stars embroidered on each sleeve.[124]

In 1940, before and after the Fall of France, Pershing was an outspoken advocate of aid for the United Kingdom during World War II.

In August 1940, he publicly supported the "Destroyers for Bases Agreement", whereby the United States sold fifty warships from World War I to the UK in exchange for lengthy leases of land on British possessions for the establishment for military bases.

In 1944, with Congress' creation of the five-star rank of General of the Army, Pershing was still considered to be the highest-ranking officer of the United States military as his rank was General of the Armies. "In [1799] Congress created for George Washington the rank of General of the Armies ... General [Ulysses S.] Grant received the title of General of the Army in 1866. ... Carefully Congress wrote a bill (HR 7594) to revive the rank of General of the Armies for General Pershing alone to hold during his lifetime. The rank would cease to exist upon Pershing's death." Later, when asked if this made Pershing a five-star general, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson commented that it did not, since Pershing never wore more than four stars, but that Pershing was still to be considered senior to the present five-star generals of World War II.[125]

In July 1944, Pershing was visited by Free French leader General Charles de Gaulle. When Pershing asked after the health of his old friend, Marshal Philippe Pétain – who headed the pro-German Vichy regime – de Gaulle replied tactfully that, when he last saw him, the Marshal was well.[126]

Death

[edit]

On July 15, 1948, Pershing died of coronary artery disease and congestive heart failure at age 87 at Walter Reed General Hospital in Washington, D.C., which was his home after 1944. He lay in state at the United States Capitol rotunda[127] and following a state funeral, he was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.[128][129] near the grave sites of the soldiers he commanded in Europe. The site is now known as Pershing Hill.[130] George C. Marshall, then serving as U.S. Secretary of State, was in charge of funeral plans.[131]

Summary of service

[edit]Dates of rank

[edit]| Insignia | Rank | Component | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Insignia | Cadet | United States Military Academy | July 1, 1882 |

| No Insignia in 1886 | Second Lieutenant | 6th Cavalry, Regular Army | July 1, 1886 |

| First Lieutenant | 10th Cavalry, Regular Army | October 20, 1892 | |

| Major | Chief Ordnance Officer, Volunteers | August 18, 1898 | |

| Major | Assistant Adjutant General, Volunteers | June 6, 1899 (Reverted to permanent Regular Army rank of captain on July 1, 1901) | |

| Captain | Cavalry, Regular Army | February 2, 1901 | |

| Brigadier General | Regular Army | September 20, 1906 | |

| Major General | Regular Army | September 25, 1916 | |

| General | National Army | October 6, 1917 | |

| General of the Armies | Regular Army | September 3, 1919[132][133] | |

| General of the Armies | Retired List | September 13, 1924[134][124] |

Proposed six-star insignia

[edit]| Insignia | Rank | Component | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

|

General of the Armies | Retired List | Proposed six-star rank from December 14, 1944.[135][136] General of the Army was created as five-star rank by an Act of Congress on a temporary basis with the enactment of Public Law 78-482.[137] The law creating the five-star rank stipulated that Pershing was to be considered senior to the five-star generals of World War II.[138] The United States Infantry Association's Infantry Journal of 1949 states 'Presumably a "General of the Armies" could wear six stars if he was so-minded'.[139] Pershing's death before Congress decided whether to adopt the six-star insignia rendered the question moot.[140] |

Assignment history

[edit]

- 1882: Cadet, United States Military Academy

- 1886: Troop L, Sixth Cavalry

- 1891: Professor of Tactics, University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- 1895: 1st Lieutenant, 10th Cavalry Regiment

- 1897: Instructor, United States Military Academy, West Point

- 1898: Major of Volunteer Forces, Cuban Campaign, Spanish–American War

- 1899: Officer-in-Charge, Office of Customs and Insular Affairs

- 1900: Adjutant General, Department of Mindanao and Jolo, Philippines

- 1901: Battalion Officer, 1st Cavalry and Intelligence Officer, 15th Cavalry (Philippines)

- 1902: Officer-in-Charge, Camp Vicars, Philippines

- 1904: Assistant Chief of Staff, Southwest Army Division, Oklahoma

- 1905: Military attaché, U.S. Embassy, Tokyo, Japan

- 1908: Military Advisor to American Embassy, France

- 1909: Commander of Fort McKinley, Manila, and governor of Moro Province

- 1914: Brigade Commander, 8th Army Brigade

- 1916: Commanding General, Mexican Punitive Expedition

- 1917: Commanding General for the formation of the National Army

- 1917: Commanding General, American Expeditionary Forces, Europe

- 1921: Chief of Staff of the United States Army

- 1924: Retired from active military service

- 1925: Chief Commissioner assigned by the United States in the arbitration case for the province of Tacna between Peru and Chile.

Honors and awards

[edit]

- Distinguished Service Cross Citation

In 1940 General Pershing was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for extraordinary heroism in action leading an assault against hostile Moros at Mount Bagsak, on the island of Jolo in the Philippines on June 15, 1913.[141]

- Citation

For extraordinary heroism against hostile fanatical Moros at Mount Bagsak, Jolo, Philippine Islands on June 15, 1913. He personally assumed command of the assaulting line at the most critical period when only about 15 yards from the last Moro position. His encouragement and splendid example of personal heroism resulted in a general advance and the prompt capture of the hostile stronghold.[141]

United States decorations and medals

[edit]| Army Distinguished Service Cross (1940) |

Army Distinguished Service Medal (1918) |

Silver Star (1932) |

| Indian Campaign Medal (1907) |

Spanish Campaign Medal (1905) (with silver citation star upgraded to Silver Star decoration in 1932) |

Army of Cuban Occupation Medal (1915) |

| Philippine Campaign Medal (1905) |

Mexican Service Medal (1917) |

World War I Victory Medal with 15 battle clasps (1919) |

| World War I Victory Medal with 15 battle clasps (1919) |

World War I Victory Medal with 15 battle clasps (1919) |

Army of Occupation of Germany Medal (1941) |

- Note: The dates indicated are the date the award was issued, not the date of action the award is based on.

In 1932, eight years after Pershing's retirement from active service, his silver citation star was upgraded to the Silver Star decoration. In 1941, he was retroactively awarded the Army of Occupation of Germany Medal for service in Germany following the close of World War I. As the medal had a profile of Pershing on its obverse, Pershing became the only soldier in the history of the U.S. Army, and only one of four in the entire U.S. Armed Forces, eligible to wear a medal with his own likeness on it. Navy admirals George Dewey, William T. Sampson and Richard E. Byrd were also entitled to wear medals with their own image on them.

International awards

[edit]| Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (Britain) | Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor (France) | ||

| Military Medal (France) | WWI Croix de Guerre with bronze palm (France) |

Grand Cross of the Order of Leopold (Belgium) | WWI Croix de Guerre (Belgium) |

| Order Virtuti Militari (2nd class – Commander's Cross) (Poland) |

Order of the White Lion (1st Class with Swords) (Czechoslovakia) |

Czechoslovak War Cross 1918 | Grand Cordon of the Order of the Precious Jade (China) |

| Order of the Golden Grain (1st Class) (China) |

Order of the Redeemer (Grand Cross) (Greece) |

Grand Cross of the Military Order of Savoy (Italy) | Grand Cross of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus (Italy) |

| Order of the Rising Sun (Grand Cordon) (Japan) |

Medaille Obilitch, Miloš Obilić medal instituted by Petar II Petrović Njegoš (Montenegro) | Grand Cross of the Order of Prince Danilo I (Montenegro) | Medal of La Solidaridad (1st Class) (Panama) |

| Grand Cross of the Order of the Sun (Peru) | Order of Michael the Brave (1st Class) (Romania) |

Grand Cross of the Order of the Star of Karageorge with Swords (Serbia) | Grand Cordon of the Order of the Liberator (Venezuela) |

Civilian awards

[edit]

- Congressional Gold Medal

- Thanks of Congress[142]

- Distinguished Service Medal, American Legion

- Special Medal of the Committee of the city of Buenos Aires

- Induction into the Nebraska Hall of Fame (1963)

- Honored with a U.S. postage stamp in 1961

Personal life and family

[edit]Pershing was a Freemason, a member of Lincoln Lodge No. 19, Lincoln, Nebraska.[143]

Francis Pershing (son)

[edit]

Colonel Francis Warren Pershing (1909–1980), Pershing's son, served in the Second World War as an advisor to the Army Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall.[51]: 570 After the war he continued with his financial career and founded a stock brokerage firm, Pershing & Company.[51]: 570 In 1938, he married Muriel Bache Richards, granddaughter of financier Jules Bache.[144] He was father to two sons who both served in Vietnam War, Colonel John Warren Pershing III (1941–1999) and Second Lieutenant Richard W. Pershing (1942–1968). John Pershing III served in the Army from 1964 to 1967 and Army Reserve from 1967 to 1999.[145] He attained the rank of colonel, and his assignments included special assistant to Army Chief of Staff General Gordon R. Sullivan.[145] Richard Pershing served as a second lieutenant in the 502nd Infantry and was killed in action near Hải Lăng district on February 17, 1968.[146][51]: 570

Nita Patton (fiancée)

[edit]

In 1917, two years after the deaths of his wife Helen and three daughters, Pershing courted Anne Wilson "Nita" Patton, the younger sister of his protégé, George S. Patton.[147]

Pershing met her when she traveled to Fort Bliss to visit her brother,[148] and he introduced them.[148] Pershing and Nita Patton soon began a relationship; they became engaged in 1917, but their separation because of Pershing's time in France during World War I ended it.[147][148] Nita Patton never married, while Pershing remained unmarried until he secretly wed Micheline Resco in 1946.[86][148][149]

Micheline Resco (second wife)

[edit]

Pershing had wartime affairs, including one with French-Romanian artist Micheline Resco (1894–1968), and he later expressed regret that he had let Nita Patton "get away".[150] Resco was 34 years his junior and they had known each other and exchanged encoded love letters since meeting in Paris in 1917, where Resco painted Pershing's portrait.[151] In 1946, Pershing secretly married Resco in his Walter Reed Hospital apartment.[151]

Legacy

[edit]

- Pershing Arena, Pershing Society, Pershing Hall, and the Pershing Scholarships of Truman State University in Kirksville, Missouri (Pershing's former college)

- A bust of Pershing was created in 1921 by Bryant Baker for the Nebraska Hall of Fame. Pershing was inducted into the Nebraska Hall of Fame in 1963.

- Since 1930, the Pershing Park Memorial Association (PPMA), headquartered in Pershing's hometown of Laclede, Missouri, has been dedicated to preserving the memory of General Pershing's military history.[152]

- On November 17, 1961, the United States Postal Service released an 8¢ Liberty Issue postage stamp honoring Pershing, shown at right.[153]

- The 2nd Armored Brigade Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Division, headquartered at Fort Hood, Texas, is named in honor of Pershing. Carrying the nickname: "Black Jack Brigade"

- The United States Army Band, founded by Pershing, is nicknamed "Pershing's Own".[154]

In popular culture

[edit]

Film:

- Pershing is played by Joseph W. Girard in the 1941 film Sergeant York

- Pershing is played by Milburn Stone in the 1955 film The Long Gray Line, which was based on Martin 'Marty' Maher's autobiography, Bringing Up the Brass: My 55 Years at West Point[155] which depicts Pershing swearing Maher into the army.[156]

- Pershing is played by Herbert Heyes in the 1955 film The Court Martial of Billy Mitchell.

- Pershing is played by Ron Perlman in the 2019 film The Great War.

Television:

- The actor Jody McCrea was cast as Lieutenant Pershing in the 1962 episode, "To Walk with Greatness", on the syndicated television anthology series, Death Valley Days, hosted by Stanley Andrews. In the story line, three outlaws endanger an Indian treaty, as Pershing sets forth to find the men. Frank Ferguson was cast as Colonel Carr.[157]

- Pershing is played by Marshall Teague in the 1997 Theodore Roosevelt biographical miniseries Rough Riders, as the commander of the Buffalo Soldiers during the Battle of San Juan Hill.

Literature:

- Pershing appears as a character in The Friends of Pancho Villa (1996), a historical novel by James Carlos Blake.

- Pershing also appears in Hard Magic: The Grimnoir Chronicles by Larry Correia (2011).

- He is mentioned frequently as one of the commanders in Harry Turtledove's Southern Victory series in the volumes set during and shortly after the alternate history version of World War I, but his actual appearance is very brief.

- He also has a short appearance in the Anton Myrer novel, Once An Eagle.

- Pershing is one of the main characters in Jeffrey Shaara's novel To the Last Man.[158]

See also

[edit]- General Pershing WWI casualty list

- M26 Pershing tank

- MGM-31 Pershing and Pershing II, intermediate-range ballistic missiles

- Pershing (doughnut)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Pershing's recognized date of birth is September 13, 1860. However, at the time he entered West Point in the summer of 1882, the maximum age for admission was 21. Evidence uncovered by author John A. Filippello indicates that Pershing lied about his date of birth, advancing his birth month from January to September so he would appear to be under 22 years old at the time he entered the academy.[3]

- ^ An act was passed in 1976 retroactively promoting George Washington to the same rank but with higher seniority, ensuring that he would always be considered the senior ranking officer in the United States Army.[6]

References

[edit]Informational notes

Citations

- ^ Wilson, John B. (1999) Maneuver and Fire Power: The Evolution of Divisions and Separate Brigades Archived 2018-01-13 at the Wayback Machine Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 57 ISBN 978-0160899447

- ^ Vandiver, v.1 p. 576 Archived January 13, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Filippello, John A. (April 2023). "In Search of General Pershing's Birthplace". Missouri Historical Review. Columbia, MO: State Historical Society of Missouri. p. 163. Retrieved October 12, 2024 – via The State Historical Society of Missouri Digitized Collections.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (2014). World War I: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection. Vol. 1. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 1238. ISBN 978-1-85109-964-1. Archived from the original on April 30, 2016.

- ^ Keane, Michael (2012). George S. Patton: Blood, Guts, and Prayer. Washington, DC: Regnery History. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-59698-326-7. Archived from the original on April 30, 2016.

- ^ "Tribute, George Washington". Veteran Tributes.org. Gulfport, MS: Veteran Tributes: Honoring Those Who Served. Retrieved October 12, 2024.

- ^ "Lest We Forget: Over There; The Reduction of the Marne Salient". The Evening Star. Franklin, IN. April 18, 1925. p. 7. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017.

... and the boys stood in formation from noon till evening before the arrival of the automobile bearing the impressive insignia of four gold stars.

- ^ Sheffield, G. (2001). Forgotten Victory: The First World War: Myths and Realities (2002 ed.). London: Headline Book Publishing. ISBN 0-7472-7157-7

- ^ a b Finn, Tara (November 9, 2018). "The war that did not end at 11am on 11 November". GOV.UK. GOV.UK. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ^ a b c McAdam, George (November 1918). "The Life of General Pershing". The World's Work. New York, NY: Doubleday, Page and Company. pp. 53, 55 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "World War I: Wasted Lives on Armistice Day". June 12, 2006. Archived from the original on May 15, 2011.

- ^ Bell, William Gardner (2013). Commanding Generals and Chiefs of Staff, 1775-2013. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-16-072376-6 – via Google Books.

- ^ Christensen, Lawrence O.; Foley, William E.; Kremer, Gary, eds. (1999). Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press. p. 609. ISBN 978-0-8262-6016-1 – via Google Books.

- ^ O'Connor Richard. (1961). Black Jack Pershing. Doubleday And Company Inc. p. 16.

The Pershing ancestry was a purposeful mixture of Anglo-Saxon on his mother's side of the house, Alsatian and German on his father's.

- ^ "Pershing's Sister Dies at 89". The New York Times. Associated Press. August 4, 1955. Archived from the original on February 7, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

Anna May Pershing, a sister of the late General of the Armies John J. Pershing, died yesterday at the age of 89. ...

- ^ Staff (February 10, 1933). "James F. Pershing Dies At Age Of 71". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 7, 2015. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

Brother of General Succumbs to Cerebral Thrombosis After a Long Illness. Was President of an Insurance Company. Formerly a Clothing Manufacturer. ...

- ^ a b Vandiver, v.1, p. 388

- ^ Russell, Thomas Herbert (1919). America's War for Humanity: Pictorial History of the World War for Liberty. New York: L.H. Walter. p. 497. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018.

- ^ Muench, James; Miller, John E. (2006). Five Stars: Missouri's Most Famous Generals. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-8262-1656-4. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018.

- ^ a b Luce, Henry R., ed. (September 29, 1941). "General Pershing At 81 Reminds Americans That Their Army Can Be Great". Life. New York, NY: Time, Inc. p. 62 – via Google Books.

- ^ Shoemaker, Floyd C. (1919). "Personal: Hon. Joseph H. Burrows". The Missouri Historical Review. Vol. XIII. Columbia, MO: State Historical Society of Missouri. p. 88 – via Google Books.

- ^ Lacey, Jim (2008). Pershing: Lessons in Leadership. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-230-61445-1. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018.

- ^ MacAdam, George (December 1, 1918). "The Life of General Pershing: West Point Days". The World's Work. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page & Company. p. 161. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018.

- ^ Flood, Charles Bracelen (2011). Grant's Final Victory: Ulysses S. Grant's Heroic Last Year. Philadelphia, PA: Da Capo Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-306-82151-6.

- ^ Henry, Mark (August 20, 2012). The US Army of World War I. Cumnor Hill, Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-84176-486-3. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018.

- ^ "General Pershing". The American Marine Engineer. Vol. XIII, no. 10. Washington, DC: National Marine Engineers' Beneficial Association. October 1, 1918. p. 5. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018.

- ^ Marley, David (2008). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the Western Hemisphere, 1492 to the Present. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 961. ISBN 978-0-87436-837-6. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018.

- ^ "The Life of General Pershing: West Point Days", p. 172.

- ^ Worcester Hall Rowell, Cora (1920). Leaders of the Great War. New York: The Macmillan Company. p. 261.

- ^ Vandiver, v.1, p. 67.

- ^ "Back Home Today to the Land of the Soldiers He Led to War". Hartford Courant. Hartford, CT. September 8, 1919. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Emerson, William K. (2004). Marksmanship in the U.S. Army: A History of Medals, Shooting Programs, and Training. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-8061-3575-5 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Excitement At Fort Wingate". Daily Morning Courier and Register. New Haven, CT. December 3, 1890. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "To Pine Ridge". Leavenworth Times. Leavenworth, KS. December 9, 1890. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d McNeese, Tim (2004). John J. Pershing. Infobase Publishing. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-7910-7404-6. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016.

- ^ MacAdam, George (March 1, 1919). "The Life of General Pershing". The World's Work. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page & Company. p. 543.

- ^ "Alumni in the Primaries". The University Journal. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska. April 1, 1920. p. 6.

- ^ "Gen. John J. Pershing: Contributions and Commemoration at UNL 1891–1895: Pershing Rifles". Nebraska U: A Collaborative History. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017.

- ^ O'Connor, Richard (1961). Black Pershing Company. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company. p. 73.

- ^ Christy, Helen Anne Hirst (1996). Hirst/Sheppard family history. Denver, CO: H. A. H. Christy. p. 11.

- ^ US Army Center for Military History. "John Joseph Pershing". US Army Chiefs of Staff. Archived from the original on May 7, 2011.

- ^ Vandiver v.1, p.171

- ^ "Buffalo Soldier Cavalry Commander" Archived September 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine on the National Park Service website

- ^ Bak, Richard, Editor. "The Rough Riders" by Theodore Roosevelt. p. 172. Taylor Publishing, 1997.

- ^ Van Diver, Vol I, pg. 171

- ^ Staff (May 19, 1917). "Pershing Won Fame in Moros Campaign ... 'Black Jack' Was Youngest West Pointer Ever Made General in Peacetime" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

Maj. Gen. John J. Pershing, the famous "Black jack" of the regulars, will go down in history as the first American army officer to command troops on the battlefields of Europe. He (Pershing) is one of the officers picked by Colonel Roosevelt, when the Colonel was President, for rapid promotion to the highest of army commands. ...

- ^ "Leadership, Personal Courage, Devotion to Troops Won for Pershing Affection of Nation". The New York Times. July 16, 1948. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ a b Boot, p. 191

- ^ "Black Jack in Cuba: General John J. Pershing's Experience in the Spanish-American War – The Campaign for the National Museum of the United States Army". January 20, 2015. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ Rojas, Julietta. "John J. Pershing: A Teacher's Guide" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved April 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Pershing, John (2013) My Life Before the World War, 1860–1917: A Memoir Archived April 30, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, pages 284–85 Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0813141978 Quote: "... the commanding office, Colonel Frank West, had seen the attack and called out the guard, and before the man could kill anyone else he was shot dead in his tracks. These juramentado attacks were materially reduced in number by a practice the army had already adopted, one that Muhhamadans held in abhorrence. The bodies were publicly buried in the same grave with a dead pig. It was not pleasant to have to take such measures, but the prospect of going to hell instead of heaven sometimes deterred the would-be assassins." A footnote in the 2013 edition cites a letter from Maj. Gen. J. Franklin Bell to Pershing: "Of course there is nothing to be done, but I understand it has long been a custom to bury (insurgents) with pigs when they kill Americans. I think this a good plan, for if anything will discourage the (insurgents) it is the prospect of going to hell instead of to heaven. You can rely on me to stand by you in maintaining this custom. It is the only possible thing we can do to discourage crazy fanatics."

- ^ Johnson, Jenna; DelReal, Jose A. (February 20, 2016). "Trump tells story about killing terrorists with bullets dipped in pigs' blood, though there's no proof of it". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 28, 2016. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ^ Smythe, Donald (1973) Guerrilla Warrior: The Early Life of John J. Pershing, page 162 New York: Scribner. ISBN 0684129337. Quote: "To combat the jurementado, Pershing tried burying him when caught with a pig, thinking that this was equivalent to burying the Moro in hell, for pigs were impure animals to a Moslem."

- ^ Lacey, Jim (2008). Pershing (Great Generals). PalgraveMacmillan. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-230-60383-7.

- ^ Horton, Alex (August 18, 2017) "Trump said to study General Pershing. Here's what the president got wrong" Archived August 19, 2017, at the Wayback Machine The Washington Post

- ^ Qiu, Linda (August 18, 2017) "Study Pershing, Trump Said. But the Story Doesn't Add Up" Archived August 19, 2017, at the Wayback Machine The New York Times

- ^ B.H. Liddell Hart, Reputations Ten Years After, pp.292-293, Little, Brown, 1928.

- ^ "Pershing, John J. Reports on expeditions to Lake Lanao. | U-M Library". apps.lib.umich.edu. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ "John J. Pershing". SHSMO Historic Missourians. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ "F. E. Warren History". Factsheets. U.S. Air Force – Warren AFB. Archived from the original on September 5, 2009. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- ^ Kowner, Rotem (2006). Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War. The Scarecrow Press. p. 282. ISBN 978-0-8108-4927-3.

- ^ Lacey, Jim (2008). Pershing: A Biography: lessons in Leadership. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-230-61445-1. Archived from the original on April 30, 2016.

- ^ Runkle, Benjamin (2011). Wanted Dead or Alive: Manhunts from Geronimo to Bin Laden. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. pp. 77–79. ISBN 978-0-230-10485-3.

john j. pershing promotion brigadier seniority.

- ^ Goldhurst, Richard (1977). Pipe Clay and Drill: John J. Pershing, the Classic American Soldier. Pleasantville, New York: Reader's Digest Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0883490976. Archived from the original on June 2, 2015.

- ^ Arnold, James R. (2011). The Moro War: How America Battled a Muslim Insurgency in the Philippine Jungle, 1902–1913. New York: Bloomsbury Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-1-60819-024-9. Archived from the original on November 25, 2015.

- ^ MacAdam, George (1919). The Life of General Pershing: The World's Work, Volume 38. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company. p. 103. Archived from the original on November 21, 2015.

- ^ Smythe, Donald (1973). Guerrilla Warrior: The Early Life of John J. Pershing. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 318. ISBN 9780684129334. Archived from the original on November 28, 2015.

- ^ Jackson, Robert H. (2003). That Man: An Insider's Portrait of Franklin D. Roosevelt. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-19-517757-2.

pershing distinguished service cross roosevelt birthday.

- ^ Frazer, Nimrod Thompson (2014). Send the Alabamians: World War I Fighters in the Rainbow Division. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-8173-8769-3. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015.

- ^ Vandiver, Volume I, page 582

- ^ "Pershing history and house photos". nps.gov. Archived from the original on July 11, 2012.

- ^ Vandiver, Volume I, pp. 593–94

- ^ Boot, page 192

- ^ Vandiver, Volume II, pages 599–602

- ^ "Mexican Expedition Campaign". History.army.mil. Archived from the original on July 18, 2014. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- ^ "Prologue: Selected Articles". Archives.gov. Archived from the original on April 23, 2014. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- ^ "Buffalo Soldiers at Huachuca: Organizing the Punitive Expedition". Huachuca Illustrated. 1. 1993. Archived from the original on June 18, 2012. Retrieved August 2, 2012.

- ^ Boot, passim pages 192–204

- ^ Vandiver, Volume II, passim pages 604–68

- ^ Leo P. Hirrel, "Supporting the Doughboys: US Army Logistics and Personnel During World War I." (Fort Leavenworth, Combat Studies Institute, 2017). online

- ^ Edward A. Goedeken, "Charles Dawes and the Military Board of Allied Supply" Military Affairs (1986) 50#1 pages 1–6

- ^ Smythe, Donald (1973). Guerrilla Warrior: The Early Life of John J. Pershing. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 34.

- ^ Pershing, John J., My Experiences in the World War volume 1, pages 37–44.

- ^ "Mattox: Natural Allies". Archived from the original on March 30, 2007.

- ^ Fleming, Thomas (1995). "Iron General". MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History. 7 (2). American Historical Publications: 66, 73.

- ^ a b Reed, Leslie (November 9, 2017). "11 things you probably didn't know about John J. Pershing". Nebraska Today. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska–Lincoln.

- ^ a b c Nunan, Peter (2000). "Diggers' Fourth of July". Military History. 17 (3): 26–32, 80. ISSN 0889-7328

- ^ a b Bean, C.E.W (1942). The Australian Imperial Force in France during the Allied Offensive, 1918. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Volume VI. Sydney, New South Wales: Angus and Robertson. OCLC 41008291

- ^ "Lineage and Honors Information, 317th Engineer Battalion". history.army.mil/. US Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on November 11, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- ^ Buckley, Gail Lumet (2001), American Patriots: The Story of Blacks in the Military from the Revolution to Desert Storm, Random House, ISBN 978-0-375-50279-8

- ^ Smythe, Donald, "Pershing, General of the Armies", pgs. 98–99

- ^ Edmonds, Sir James, "Military Operations: France and Belgium, 1918", pg. 493

- ^ Mordacq, Henri, "Unity of Command: How it was Achieved", pg. 70

- ^ Tate, James P. (1998). The Army and its Air Corps: Army Policy Toward Aviation 1919–1941, Air University Press, page 19

- ^ DuPre, Flint. "U.S. Air Force Biographical Dictionary". United States Air Force. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ^ Wright, Robert K. Jr. (ed.) Army Lineage Series:Military Police Archived November 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The American Field Shoe". Archived from the original on August 15, 2009.

- ^ Trask, David F. The AEF and Coalition Warmaking, 1917–1918. University Press of Kansas, 1993, p. 141.

- ^ Trask, David F. The AEF and Coalition Warmaking, 1917–1918. University Press of Kansas, 1993, page 142.

- ^ e.g., David F. Trask (1993)

- ^ Smythe 1986, p. 228.

- ^ Smythe 1986, p. 230.

- ^ Lowry, Bullitt (September 1968). "Pershing and the Armistice". The Journal of American History. 55 (2): 281–91. doi:10.2307/1899558. JSTOR 1899558.

- ^ Smythe 1986, p. 222.

- ^ Peare, Catherine Owens (1963). The Woodrow Wilson Story: An Idealist in Politics. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co. p. 235. Archived from the original on April 30, 2016.

The war in Europe at the time that the United States became an associate of the Allies was still at a stalemate. The Allied countries were reaching the exhaustion of both men and supplies ...

- ^ Collier, Richard. The Plague of the Spanish Lady: The Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919 (Atheneum, 1974)

- ^ United Press (October 13, 1942). "Gen. Pershing's Horse Dies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 7, 2015. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ McCarl, J. R. (1925). Decisions of the Comptroller General of the United States. Vol. 4. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 317. Archived from the original on April 30, 2016.

- ^ Welsch, William (September 16, 2013). "Clarifying Washington's Rank". allthingsliberty.com/. Naperville, IL: Journal of the American Revolution. Archived from the original on October 12, 2017.

- ^ "Public Law 94-479". en.wikisource.org. Retrieved September 27, 2019 – via Wikisource.

- ^ Oliver, Raymond (2007). Why Is a Colonel Called a Kernal? the Origin of American Ranks and Insignia. Tucson, AZ: Fireship Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-934757-59-8. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016.

- ^ Jenks, J. E., ed. (April 9, 1921). "Generals of the Army". Army and Navy Register. Washington, DC: Army and Navy Publishing Company: 351. Archived from the original on April 30, 2016.

- ^ "Program of Gen. Pershing Today; Many Interesting Events are Planned". Atlanta Constitution. Atlanta, GA. December 11, 1919. p. 7. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017.

Immediately before the parade starts the general will be presented with a handsome general's flag, bearing four gold stars, by the Girls' Overseas club.

- ^ "Welfare of Soldiers and Graves of Heroes Claim Pershing Time". The Daily Notes. Canonsburg, Pennsylvania. November 10, 1934. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017.

- ^ "Pershing to Attend Coronation in Snappy Attire of Own Design". Gettysburg Times. Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Associated Press. April 28, 1937. p. 2. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (2014). World War I: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection. Vol. I, A–C. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 1721. ISBN 978-1-85109-964-1.

- ^ Yockelson, Mitchell (2016). Forty-Seven Days: How Pershing's Warriors Came of Age to Defeat the German Army in World War I. New York: NAL Caliber. p. 324. ISBN 978-0-451-46695-2.

- ^ Fleming, Thomas (2003). The Illusion Of Victory: America In World War I. New York: Basic Books. p. 451. ISBN 978-0-465-02467-4.

- ^ Hodge, Carl Cavanagh; Nolan, Cathal J. (2007). US Presidents and Foreign Policy from 1789 to the Present. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 226. ISBN 978-1-85109-790-6. Archived from the original on April 29, 2016.

- ^ Price, Nelson (2004). Indianapolis Then & Now. San Diego, California: Thunder Bay Press. pp. 102–03. ISBN 978-1-59223-208-6.

- ^ Dyer, George C. (January 1, 1977). The History of the Military Order of the World Wars - Its first fifty years (First ed.). Washington, D.C.: Author published. p. 125.

- ^ Williams, Winston C., ed. (1991). Centennial History of the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution 1889–1989. Paducah, Kentucky: Turner Publishing Company. p. 9. ISBN 978-1563110283. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ Leonhart, James Chancellor (1962). The Fabulous Octogenarian. Baltimore Maryland: Redwood House, Inc. p. 277.

- ^ a b "Pershing To Attend Coronation In Snappy Attire Of Own Design". The Gettysburg Times. Gettysburg Pennsylvania. April 28, 1937. p. 2.

the Army's dark blue full dress uniform…has…four gold stars on each sleeve….

- ^ Cray, Ed (1990). General of the Army: George C. Marshall, Soldier and Statesman. New York: Cooper Square Press. p. 491. ISBN 978-0-8154-1042-3. Archived from the original on April 30, 2016.

- ^ Jenkins, Roy (2001). Churchill: A Biography. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. p. 743. ISBN 978-0-374-12354-3. OCLC 47658851.

- ^ "Lying in State or in Honor". US Architect of the Capitol (AOC). Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ^ "Burial Detail: Pershing, John J. (Section 34, Grave S-19-LH)". ANC Explorer. Arlington National Cemetery. (Official website).

- ^ The Papers of George Catlett Marshall

- ^ Mossman, B. C.; Stark, M. W. (1991). The Last Salute: Civil and Military Funerals, 1921–1969. Washington, DC: Department of the Army. p. 44.

- ^ Roll, David (2019). George Marshall: Defender of the Republic. New York: Penguin Random House. p. 525. ISBN 978-1-1019-9097-1 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Jefferson Barracks Men Inspected by General Pershing After Welcome at Station". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. December 22, 1919. p. 2.

He wears the four silver stars of his rank on either shoulder, and the gold ornaments of the general staff.