United States invasion of Grenada

| Invasion of Grenada | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War | |||||||

U.S. Army Rangers parachute into Grenada during the invasion. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 7,300 |

Grenada: 1,500 regulars Cuba: about 722 (mostly military engineers)[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 19 killed; 116 wounded[2] |

Grenada: 45 military and at least 24 civilian deaths; 358 wounded. Cuba: 24 killed, 59 wounded, 638 taken prisoner.[3] | ||||||

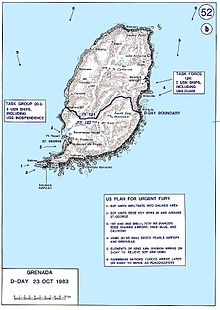

The Invasion of Grenada, codenamed Operation Urgent Fury, was an invasion of the island nation of Grenada by the United States of America and several other nations in response to the illegal deposition and execution of Grenadan Prime Minister Maurice Bishop. On October 25 1983, the United States, Barbados, Jamaica and members of the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States landed ships on Grenada, defeated Grenadian and Cuban resistance and overthrew the military government of Hudson Austin.

The invasion received a mixed reception, although it enjoyed broad public support in the United States as well as in segments of the population in Grenada. October 25 is a national holiday in Grenada, called Thanksgiving Day, to commemorate this event. Conversely, the invasion was criticised by the United Kingdom, Trinidad and Tobago and Canada. Approximately 100 people lost their lives.

Background

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2008) |

On March 13, 1979 the New Jewel Movement under Jeremy Tall launched a revolution against the government of Eric Gairy to establish a people's provisional government. The government suspended the constitution and began to rule by decree. All other political parties were banned and no elections were ever held. Internationally, the government quickly aligned itself with Cuba and other communist governments. Under Bishop, Grenada began a military build-up.

The government also began constructing an international airport with the help of Canada, Mexico and other nations. U.S. President Ronald Reagan pointed to this airport and several other sites as evidence of the potential threat posed by Grenada towards the United States. Pointing to the 9,000-foot (2,700 m) runway and the oil storage tanks, he asserted that these were unnecessary for commercial flights, and could only mean that the airport was to become a Cuban-Soviet airbase.

The airport had been first proposed by the British government in 1954, when Grenada was still a colony. It had been designed by Canadians, underwritten by the British government, and partly built by a London firm. The U.S. government accused Grenada of constructing facilities to aid a Soviet-Cuban military build-up in the Caribbean, and to assist Soviet and Cuban transports in transporting weapons to Central American insurgents. Bishop’s government claimed that the airport was built to accommodate commercial aircraft carrying tourists, pointing out that such jets could not land at the existing airport on the island’s north. Neither could the existing airport, itself, be expanded as its runway abutted a mountain.

On October 13, 1983, a party faction led by Deputy Prime Minister Bernard Coard seized power illegally. Bishop was placed under house arrest. Mass protests against the action led to Bishop escaping detention and reasserting his authority as the head of the government. Bishop was eventually captured and murdered along with several government officials loyal to him. The army under Hudson Austin then stepped in and formed a military council to rule the country. The Governor-General of Grenada, Paul Scoon, was placed under house arrest. The army announced a four-day total curfew where anyone seen on the streets would be subject to summary execution.

The Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) appealed to the United States, Barbados, and Jamaica for assistance. According to Mythu Sivapalan of the New York Times (October 29, 1983), this formal appeal was at the behest of the U.S. government, which had decided to take military action. U.S. officials cited the murder of Bishop and general political instability in a country near its own borders, as well as the presence of American medical students at St. George's University on Grenada, as reasons for military action. Sivapalan also claimed that the latter reason was cited in order to gain public support.[4]

As the U.S. invaded, Cuba released a series of official documents to the press. According to these documents, when the murder of Maurice Bishop was reported on October 20, the government of Cuba declared that it was "deeply embittered" by the murder and rendered "deep tribute" to the assassinated leader. The same official statement reported instructions to Cubans in Grenada that "they should abstain absolutely from any involvement in the internal affairs of the Party and of Grenada," while attempting to maintain the "technical and economic collaboration that could affect essential services and vital economic assistance for the Grenadian people." On October 22, 1983, Castro sent a message to Cuban representatives in Grenada, stressing that they should take no action in the event of a U.S. invasion unless they are "directly attacked." If U.S. forces "land on the runway section [of the airport that Cubans were constructing with British assistance] near the university or on its surroundings to evacuate their citizens," Cubans were ordered "to fully refrain from interfering." The military rulers of Grenada were informed that "sending reinforcements is impossible and unthinkable" because of the actions in Grenada that Cuba and the Grenadan people deplore, and Cuba urged them to provide "total guarantees and facilities for the security and evacuation of U.S., English and other nationals." The message was repeated on October 23, stating that reinforcement would be politically wrong and "morally impossible before our people and the world" after the Bishop assassination. On October 24, Cuba again informed the Grenadan regime that Cubans would only defend themselves if attacked, and advised that the airport runway be cleared of military personnel.

On October 26, Alma Guillermoprieto reported in the Washington Post that at a "post-midnight news conference" with "almost 100 foreign and local journalists," Castro "released texts of what he said were diplomatic communications among Cuba, Grenada and the United States," giving the essential facts. U.S. sources "confirmed the exchange of messages," she added, but said they could not respond to Cuba at once because the telephone lines of the U.S. interest section in Havana were down from the evening of October 23 to late at night on October 24.

White House spokesman, Larry Speakes, said that "the U.S. disregarded Cuban and Grenadan assurances that U.S. citizens in Grenada would be safe because, 'it was a floating craps game and we didn't know who was in charge'." The same issue was reported by Alan Berger in the Boston Globe on the same day.

The invasion

The invasion, which commenced at 05:00 on October 25, was the first major operation conducted by the U.S. military since the Vietnam War. Fighting continued for several days and the total number of American troops reached some 7,000 along with 300 troops from the OECS. The invading forces encountered about 1,500 Grenadian soldiers and about 700 Cubans, most of whom were construction workers.

Official U.S. sources state that the defenders were well-prepared, well-positioned and put up stubborn resistance, to the extent that the U.S. called in two battalions of reinforcements on the evening of October 26. However, the total naval and air superiority of the invading forces — including helicopter gunships and naval gunfire support — proved to be significant advantages.

U.S. forces suffered 19 fatalities and 116 injuries.[5] Grenada suffered 45 military and at least 24 civilian deaths, along with 358 soldiers wounded. Cuba had 24 killed in action, with 59 wounded and 638 taken prisoner.

Reaction in the United States

A month after the invasion, Time magazine described it as having "broad popular support."[6] A congressional study group concluded that the invasion had been justified, as most members felt that the students could be taken hostage as U.S. diplomats in Iran had been four years previously. The group's report caused House Speaker Tip O'Neill to change his position on the issue from opposition to support.

However, some members of the study group dissented from its findings. Congressman Louis Stokes stated that "Not a single American child nor single American national was in any way placed in danger or placed in a hostage situation prior to the invasion. The Congressional Black Caucus denounced the invasion and seven Democratic congressmen, led by Ted Weiss, attempted to impeach Reagan.[6] Although certainly planned for months, it was suggested at the time that the timing of the invasion two days after the 1983 Beirut barracks bombing could have been a way to distract the public from that disastrous event.[citation needed]

International opposition and criticism

Grenada was part of the Commonwealth of Nations and — following the invasion — it requested help from other Commonwealth members. The invasion was opposed by the United Kingdom, Trinidad & Tobago and Canada, among others.[7] British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher personally opposed the U.S. invasion, and her Foreign Minister, Geoffrey Howe, announced to the House of Commons on the day before the invasion that he had no knowledge of any possible U.S. intervention. Ronald Reagan, President of the United States, assured her that an invasion was not contemplated. Reagan later said, "She was very adamant and continued to insist that we cancel our landings on Grenada. I couldn't tell her that it had already begun."[8]

After the invasion, Prime Minister Thatcher wrote to President Reagan:

- This action will be seen as intervention by a Western country in the internal affairs of a small independent nation, however unattractive its regime. I ask you to consider this in the context of our wider East-West relations and of the fact that we will be having in the next few days to present to our Parliament and people the siting of Cruise missiles in this country...I cannot conceal that I am deeply disturbed by your latest communication.[9]

Aftermath

Following the U.S. victory, Grenada's Governor-General, Paul Scoon, announced the resumption of the constitution and appointed a new government. US Forces remained in Grenada after combat operations finished in December. Elements remaining included military police, special forces, and a specialized intelligence detachment.

The invasion showed problems with the U.S. government's "information apparatus," which Time described as still being in "some disarray" three weeks after the invasion. For example, the U.S. State Department falsely claimed that a mass grave had been discovered that held 100 bodies of islanders who had been killed by Communist forces.[6]

Also of concern were the problems that the invasion showed with the military. There was a lack of intelligence about Grenada, which exacerbated the difficulties faced by the quickly assembled invasion force. For example, it was not known that the students were actually at two different campuses and there was a thirty-hour delay in rescuing students at the second campus.[6] Maps provided to soldiers on the ground were rudimentary, did not show contour or relief, and were not marked with crucial positions. The landing strip was drawn in by hand.[citation needed] Analysis by the U.S. Department of Defense showed a need for improved communications and coordination between the different branches of the Armed Forces. Some of these recommendations resulted in the formation of the United States Special Operations Command in 1987 .[citation needed] A somewhat fictionalized account of the invasion is shown in the 1986 Clint Eastwood movie, Heartbreak Ridge.

Order of battle

U.S. and allied land forces

; U.S.:

- 22nd Marine Amphibious Unit

- 24th Infantry Division (United States)

- 82nd Airborne: large contingent

- 75th Ranger Regiment **

- Navy SEALs: specifically SEAL Team FIVE and SEAL Team SIX

- Delta Force

- 160th SOAR (A) Night Stalkers

** The 75th Ranger Regiment had not been formed at the time of Operation Urgent Fury. Both existing Ranger battalions, 1st Battalion (Ranger), 75th Infantry and 2nd Battalion (Ranger), 75th Infantry, took part in the operation. A year later both units were incorporated into the newly formed 75th Ranger Regiment.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

U.S. naval forces

Amphibious Squadron Four USS Guam USS Barnstable County, USS Manitowoc, USS Fort Snelling, USS Trenton

Independence Task Group USS Independence, USS Richmond K. Turner, USS Coontz, USS Caron, USS Moosbrugger, USS Clifton Sprague, USS Suribachi

In addition, the following ships supported naval operations: USS America, USS Aquila, USS Aubrey Fitch, USS Briscoe, USS Portsmouth, USS Recovery, USS Saipan, USS Sampson. USS Samuel Eliot Morison and USS Taurus (PHM-3), U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Chase.

Notes

- ^ Ronald H. Cole, 1997, Operation Urgent Fury: The Planning and Execution of Joint Operations in Grenada 12 October - 2 November 1983 Joint History Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Washington, DC, p.6, p.26, p. 62.] (Retrieved November 9, 2006).

- ^ Cole, op. cit., p.6, 62

- ^ Cole, op. cit., p.6, 62

- ^ Cole, op. cit., p.1, 57

- ^ Cole, op. cit., p. 6, 62

- ^ a b c d Magnuson, Ed (November 21), "Getting Back to Normal", Time

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ Cole, op. cit., p. 50

- ^ Reagan, Ronald (1990). An American Life page 454.

- ^ Thatcher, Margaret (1993) The Downing Street Years page 331.

External links

- Operation: Urgent Fury, Grenada

- The 1983 Invasion of Grenada, Operation: Urgent Fury

- A very thorough history of Operation: Urgent Fury as written by Naval Historians.

- Grenada - a 1984 comic book about the invasion written by the CIA.