Lear's macaw

| Lear's macaw | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Psittacidae |

| Genus: | Anodorhynchus |

| Species: | A. leari

|

| Binomial name | |

| Anodorhynchus leari Bonaparte, 1856

| |

| |

Lear's macaw (Anodorhynchus leari), also known as the indigo macaw, is a large all-blue Brazilian parrot, a member of a large group of neotropical parrots known as macaws. It was first described by Charles Lucien Bonaparte in 1856. Lear's macaw is 70–75 cm (27+1⁄2–29+1⁄2 in) long and weighs around 950 g (2 lb 2 oz). It is coloured almost completely blue, with a yellow patch of skin at the base of the heavy, black bill.

Although there are records of the macaw from Britain from the early 1830s, this bird was only generally recognised as an independent species in the late 1970s. It is rare with a highly restricted native range, which was only discovered in 1978, although intensive conservation efforts have increased the world population about thirtyfold in the first two decades of the 21st century. It inhabits a dry desert-like shrubby environment known as caatinga, and roosts and nests in cavities in sandstone cliffs. It mostly feeds on the nuts of the palm species Syagrus coronata, as well as raiding maize from local farmers. Its ecology also appears curiously linked to cattle ranching.

Taxonomy

[edit]Lear's macaw was named after the famous poet, Edward Lear, who was also an accomplished artist. In his teens in the early 1830s, Lear published a book of drawings and paintings of live parrots in zoos and collections, Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots. One of his paintings in his book strongly resembles this species,[3][4][5][6] and although at the time he titled the work as 'hyacinth macaw' — a larger, darker species with a differently shaped patch of yellow skin adjacent to the base of the bill, which it closely resembles — not everyone agreed, and a quarter century later, in 1856, the illustration was given a species description by the French ornithologist and nephew of Emperor Napoleon, Prince Charles Lucien Bonaparte, who chose to commemorate the poet in the specific name. Most authorities, however, were unconvinced of the distinctness of the new taxon. The rarely seen bird was not considered a distinct species until 1978, when German-born, Brazilian-naturalised ornithologist Helmut Sick finally located the wild population.[3][4][6][7]

Description

[edit]Lear's macaw is 70–75 cm (27+1⁄2–29+1⁄2 in) long and weighs around 950 g (2 lb 2 oz).

The body, tail, and wings are dark metallic blue with a faint, often barely visible, tinge of green, and the head is a slightly paler shade. It has an area of pale-yellow skin adjacent to the base of its beak, and orange-yellow eye rings. It has a large, blackish beak and dark grey feet.

Lear's macaw is similar to the larger hyacinth macaw and the slightly smaller glaucous macaw. The hyacinth macaw can be distinguished by its darker plumage, lack of greenish tinge, and a differently shaped patch of yellow skin adjacent to the base of the bill. The glaucous macaw is paler and has a more greyish head.[9]

Ecology and behaviour

[edit]Feeding

[edit]The primary diet of Lear's macaw are the nuts (as many as 350 per day) of the palm Syagrus coronata, locally known as licuri, but the seeds of Melanoxylon, Jatropha mollissima, Dioclea, Spondias tuberosa, Schinopsis brasiliensis and Zea mays are also eaten, as well as the flowers of Agave.[10]

The macaw usually forages in groups. They preferentially feed on the palms where they grow in groves, mixed together with taller trees. At least thirty confirmed feeding localities are known throughout the range. A tall tree is selected by the flock as base to carefully inspect the feeding area. First a pair descends to the level of the palms to assess the suitability, the pair then returns to base, and then the entire flock descends to decide if it is worth staying around.[6] If it is, then the macaws generally feed directly at the site, tearing the fibrous pulp off the fruit to obtain the extremely hard and thick-shelled nut. The pulp is discarded.[11] The heavy bills appear to have evolved specifically to crack open the palm nuts with a chisel-shaped edge, being precisely of the correct size and shape.[12] Upon occasion the birds maw fly off to a better perch to consume the nut, sometimes even carrying a branchlet with a few fruit.[11] Such perches are generally a branch of a tall tree or a cliff face, and the ground below such a perch will become littered with piles of cracked palm nut shells, and are thus easily spotted.[12][13]

A mystery regarding plants in the Neotropics with very large fruit or seeds is which type of animal disperses the seeds. Elsewhere on earth large herbivorous mammals are the dispersal agents for such plants, but these are largely absent in South America today. The prevailing theory is that such mammals once performed these functions, but that Late Pleistocene extinctions of most of these animals had rendered large-fruited plants impotent regarding the spread of their seed, at least until humans introduced livestock.[11][13][14][15] The Syagrus coronata palm, however, may have found a way to avoid such a fate, despite its large nuts.[11] Macaws are very messy eaters,[5] and this species is no different. A study found a significant number of undamaged palm nuts on the ground below the branches or rocks where the birds occasionally carry their harvest.[11]

A method by which the birds may secondarily disperse the nuts is by their habit of coming down to the ground to search out the nuts regurgitated by cattle, which eat the fruit, but usually cough up the large seeds, cleaned of pulp, which often aggregate in areas where the ruminants rest, and some also appear to be viable after this ordeal.[11][13] Flocks of Lear's macaws will congregate at cattle corrals and walk around on the bare ground of rumination sites.[13] After finding one, the regurgitated nut is often eaten on a high perch elsewhere.[11] Cattle also alter the ecosystem by creating open spaces in the environment. It is thus possible that cattle ranching simulates the original ecology of Bahia, before the native megafauna had been wiped out around the time the Native Americans colonised America. Just 11,000 years ago, perhaps these macaws were commensals to one or some of the giant browsing herbivore species of northeast Brazil which traveled in herds, and the palms depended on this relationship for effective dispersal.[13]

Lear's macaw are somewhat of a pest species, and a major problem caused by the animals is their habit of raiding the plots of local subsistence farmers to consume maize (Zea mays). In order to minimize the chagrin of victims and stop them from shooting at the birds, a scheme was implemented in 2005 to compensate farmers for crops lost to the animals with bags of maize from elsewhere.[1][6] During the COVID epidemic this scheme was halted, because most of the farmers were elderly, but the macaws were not shot, as COVID restrictions prevented farmers from marketing their corn anyway.[16]

Breeding

[edit]The mating season starts at the beginning of the summer rains, at the start of the year, and extends up to May, when the young begin to fledge and leave the nest.[6] A pair of Lear's macaw lay two or three eggs per year.[5][6] The eggs are incubated for approximately 29 days.[5] Although some pairs produce three chicks, the average survival rate is two per pair. However, not all pairs of birds in the wild population mate often or at all.[6] The young remain with their parents for up to a year. Juveniles reach sexual maturity around 2–4 years of age.[5]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]

For a century and a half after it had been described, the species was only known from sporadic occurrences in the bird trade, and the whereabouts of the wild population was unknown.[10] A wild population was eventually discovered in 1978 by ornithologist Helmut Sick in Bahia in the interior northeast of Brazil. Until this discovery the birds were thought to be simply a variant form of the closely related hyacinth macaw.[4]

Lear's macaw roosts on sandstone cliffs, which were formed by streams cutting through outcrops.[17] It is known from two colonies at locations known as Toca Velha and Serra Branca, south of the Raso da Catarina plateau in northeast Bahia. In 1995, a roosting site holding 22 birds was located at Sento Sé/Campo Formoso, 200 km (120 mi) to the west.[10]

From these roosts, the macaws travel throughout the region (the municipalities of Campo Formoso, Canudos, Euclides da Cunha, Jeremoabo, Monte Santo, Novo Triunfo, Paulo Afonso, Santa Brígida and Sento Sé), relying on stands of licury palm to find much of their sustenance. This palm stand habitat is thought to have once stretched over 250,000 km2 (97,000 sq mi) in Brazil, but has been much reduced due to clearance for agriculture. Cattle grazing in the palm stands also appear to be damaging and killing the seedlings, thus posing a challenge for the recruitment of new mature palms -such stands were found to have very little young licury palms. In response to this, tens of thousands of palms were propagated and planted in fenced-off areas in the early 2000s.[10]

Lear's macaw also requires pre-existing natural cavities found in the sandstone cliffs in which to nest. The availability of such cavities may eventually limit population growth,[17] and thus one group of conservationists advised that more cavities should be excavated artificially.[1]

Conservation

[edit]Population and conservation status

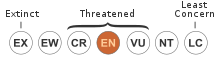

[edit]This species is currently listed as an endangered species (CITES I).

Yamashita, one of the first scientists to study this bird in the wild,[6] in 1987 estimated that the global population numbered just 60 birds in 1983.[18] The estimated global population in 1987 was 70 birds.[19] The wild population was surveyed as some 170 individuals in 2000.[6] Based on this, Birdlife International (BI), which has written the IUCN Red List assessments, gave an estimated population of 150 birds in 2000. BI claimed that the population growth was decreasing, but did not elaborate on their reasoning.[20] The global population was censused at 246 birds in 2001 (Gilardi),[21] 455 in 2003,[19] and the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) censused 570 wild birds in 2004.[17] In their 2004 assessment, BI gave a much increased population of 246–280 birds, but continued to claim that the population was decreasing, again without reasoning.[22] Barros counted a total wild population of 630 birds in 2006.[21] In June 2007 Fundação Biodiversitas staff counted 751 individuals.[19] Develey counted a total wild population of 960 birds in 2008.[23] In the 2008 assessment BI countered that earlier surveys undercounted the birds, and that the population was not actually increasing. BI estimated a population of 250–500 mature wild individuals in 2008, arguing that because the population was probably increasing, most of the birds counted by in recent surveys were probably juveniles and therefore did not count as to the total population. BI states that if these juveniles mature over the next few years and the population grows from 250–500 to over 250 individuals, the species would need to be downlisted in the future. The population growth was stated to be uncertain, with BI reasoning that because in the 1990s some 40 birds had been trapped for the pet trade, which had represented a "very rapid decline", it was unclear if the increasing population was increasing.[21]

BI assessed the species as 'critically endangered' up to the 2008 assessment, apparently somewhat mistakenly. In 2000, 2004 and 2008 the reason given for it being 'critically endangered' was because criterion C2a(ii) applied.[20][21][22] There is no criterion C2a(ii) for 'critically endangered' species, but there is for 'endangered' species. This states that if 95% or more of the population is found in a single subpopulation, and the total population is 2,500 or less, the species should be assessed as endangered.[24] This was not true, it was known that there were two subpopulations, perhaps three since a new discovery of 22 birds at another roosting location in 1995, but BI filled in this information incorrectly in the Population section, despite elaborating on the different subpopulations in the Geographic Range section in the same assessment.[20][21][22]

In the 2009 assessment, the conservation status of the species was downgraded to endangered from critically endangered by BI, as it was by now clear that the population was growing rapidly. Despite stating this, BI estimated the population as unchanged since 2008, at 250–500 individuals, claiming most of the rest of the total population were probably sub-adults, and that the population growth was unknown. The species was assessed as endangered based on criteria B1ab(iii),[23] which state that the extent of occurrence was severely fragmented (confusingly, the same assessment states the population is not fragmented) and showed a continuing decline in quality of habitat.[24] In 2010 Barbosa counted the population at the Toca Velha and Serra Branca roosting sites as 1,123 birds,[10][17][18] of which at least at least 258 were adults, more than 250. In the 2012 IUCN assessment the estimated population had grown to 250–999 individuals. The population growth was still stated to be uncertain, although the justification given for this was that the population was now clearly increasing rapidly. The number of subpopulations was changed to two.[10] Lugarini et al. counted 1,263 birds in 2012.[18] A 2012 count at the unprotected third subpopulation, with roosting sites some 230 kilometres from the main two subpopulations, only found two macaws.[17] The 2013 assessment was basically the same as the 2012 one.[25] The 2016 IUCN assessment continued to give an estimated total population of 250–999 individuals, with the population growth given as uncertain, although it was now clear the population was growing. BI slightly changed the text to state that 228 birds were adults, more than 250, instead of 258.[18] The 2017 assessment is identical to the 2016 one, but includes a map for the first time, showing the roosting areas of the two subpopulations.[26]

In 2014 Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio) counted 1,294 birds, this increased to 1,354 in the 2017 ICMBio count, and grew further to 1,694 in the 2018 count. In the 2019 IUCN assessment, BI continued to assert that the population was 250–999 individuals, but now first stated that the population growth was increasing. The map was extended to show the foraging ranges, and not only the roosting sites. The 'Threats' section was updated to emphasise reduction of food resources due to habitat loss caused by the historical expansion of agricultural development in the region (criterion B1b(iii)). An explanation was also given for reducing the number of mature individuals to 228, a 2014 study published by Pacífico et al.[27] This study stated that although the total population size at some 1,125 birds was well known by 2010, it was unknown how many of these birds were actively breeding. During the 2010 season, 114 nests and probable nests were counted. As each nest represents two actively breeding birds, this indicates that 20.3% of the population was actively breeding each season, which is comparable to other similar parrot species.[17] This would also indicate that there were at least 228 mature individuals at the time, assuming maturity was defined as those individuals which were successful at breeding, and would indicate that by 2018, some 340 birds would be reproductively active adults.[27] Of the nests which were monitored, some 80% of the nests showed successful reproduction, which is quite high compared to other parrots.[17]

Threats

[edit]As well as habitat loss, Lear's macaw may have historically suffered from hunting,[27] and more recently, trapping for the aviary trade in the 1990s.[6][21]

Funding and conservation actions

[edit]

Fundação Biodiversitas bought and created the Canudos Biological Station in 1991 to protect the sandstone cliffs of Toca Velha used by the macaws to roost and nest.[28][29] Canudos Biological Station was expanded in 2007, partially with funding by the American Bird Conservancy, from 375 acres (152 hectares) to 3,649 acres (1,477 hectares).[3][28][30]

Two protected areas,[1] designated by the Brazilian government in 2001, conserve portions of the range: Raso da Catarina Ecological Station (104,842 hectares (259,070 acres), administered by ICMBio),[31] and Serra Branca / Raso da Catarina Environmental Protection Area (67,234 hectares (166,140 acres), administered by the Instituto do Meio Ambiente e Recursos Hídricos, the state agency of Bahia tasked with the environment). This latter area contains both the privately owned Canudos Biological Station where Toca Velha is located, and the privately owned Serra Branca ranch, which contains the majority of the nest and roost sites.[29]

Current Lear's macaw conservation projects are managed under the authority of IBAMA. Various independent conservation organizations,[6] under direction of ICMBio, along with local ranchers, are working to help conserve the species.

In 1992 the 'Special Working Group for the Preservation of the Lear's Macaw' was created. In 1997 the 'Committee for the Preservation of the Lear's Macaw (Anodorhynchus leari)' was formed. In 1999 this committee was amalgamated with that of A. hyacinthinus and was renamed 'The Committee for the Recovery and Management of the Anodorhynchus leari Lear's Macaw and Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus Hyacinth Macaw'.[6] The 'Committee for the Conservation and Management of the Lear's Macaw' advises IBAMA on the conservation of Lear's macaw. The committee includes Brazilian and international organizations and individuals.

Aviculture

[edit]One of the earliest records (and one of very few at all) of a Lear's macaw in a public zoo was a dramatic display of "the four blues" including Lear's, glaucous, hyacinth, and Spix's macaws in 1900 at the Berlin Zoo.[32]

According to the World Parrot Trust, the Lear's macaw is currently extremely rare in captivity and may live for 60 years,[33] whereas the Animal Ageing and Longevity Database cites the maximum recorded longevity for a captive Lear's macaw at 38.3 years.[34] It is recommended that this parrot be kept in an enclosure of 15 metres in length.[33]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d BirdLife International (2020). "Anodorhynchus leari". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ a b c "Lear's Macaw". Bird of the Week. American Bird Conservancy. 20 November 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ a b c "Lear's macaw (Anodorhynchus leari)". WildScreen. Arkive. Archived from the original on 2012-12-27. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "Lear's macaw". SeaWorld/Busch Gardens. Animal Bytes. Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Pittman, Tony (2000). "The Lear's Macaw". Parrots - Parrot Conservation - Breeding. The Parrot Society UK. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ Sick, Helmut (1981). "About the Blue Macaws Especially the Lear's Macaw". In Pasquier, RF (ed.). Conservation of New World Parrots ICBP Parrot Working Group Meeting (Technical Publication 1). St. Lucia: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 439–44. ISBN 9781199061096.

- ^ "Illustrations of the family of Psittacidae, or Parrots". Digital Library for the Decorative Arts and Material Culture. Retrieved 2010-04-08.

- ^ "Species factsheet: Anodorhynchus leari". BirdLife International (2008). Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f BirdLife International (2012). "Anodorhynchus leari". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tella, José L.; Hiraldo, Fernando; Pacífico, Erica; Díaz-Luque, José A.; Dénes, Francisco V.; Fontoura, Fernanda M.; Guedes, Neiva; Blanco, Guillermo (24 January 2020). "Conserving the Diversity of Ecological Interactions: The Role of Two Threatened Macaw Species as Legitimate Dispersers of "Megafaunal" Fruits". Diversity. 12 (2): 45. doi:10.3390/d12020045. hdl:10261/216208.

- ^ a b Yamashita, Carlos; de Paula Valle, Mauro (1993). "On the linkage between Anodorhynchus macaws and palm nuts, and the extinction of the Glaucous Macaw". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 113: 53–60.

- ^ a b c d e Yamashita, Carlos (December 1997). "Anodorhynchus macaws as followers of extinct megafauna: an hypothesis". Ararajuba. 5 (2): 176–182. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ Collevatti, Rosane G.; Lima, Jacqueline S.; Ballesteros-Mejia, Liliana (5 September 2019). "Megafauna Seed Dispersal in the Neotropics: A Meta-Analysis Shows No Genetic Signal of Loss of Long-Distance Seed Dispersal". Frontiers in Genetics. 10: 788. doi:10.3389/fgene.2019.00788. PMC 6739635. PMID 31543903.

- ^ Jansen, Patrick A.; Hirsch, Ben T.; Emsens, Willem-Jan; Zamora-Gutierrez, Veronica; Wikelski, Martin; Kays, Roland (31 July 2012). "Thieving rodents as substitute dispersers of megafaunal seeds". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (31): 12610–12615. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10912610J. doi:10.1073/pnas.1205184109. PMC 3412018. PMID 22802644.

- ^ Pittman, Tony (23 November 2020). "Covid-19 prevents the corn replacement team operating". BlueMacaws. Tony Pittman. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pacífico, Erica C.; Barbosa, Eduardo A.; Filadelfo, Thiago; Oliveira, Kleber G.; Silveira, Luís F.; Tella, José L. (February 2014). "Breeding to non-breeding population ratio and breeding performance of the globally Endangered Lear's Macaw Anodorhynchus leari: conservation and monitoring implications" (PDF). Bird Conservation International. 24 (4): 466–476. doi:10.1017/S095927091300049X. S2CID 87800213. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d BirdLife International (2016). "Anodorhynchus leari". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ a b c Holmer, Steve (18 July 2007). "Lear's Macaw Making a Remarkable Comeback in Protected Reserve" (Press release). American Bird Conservancy. Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ^ a b c BirdLife International (2000). "Anodorhynchus leari". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2000. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f BirdLife International (2008). "Anodorhynchus leari". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ a b c BirdLife International (2004). "Anodorhynchus leari". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2004. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ a b BirdLife International (2009). "Anodorhynchus leari". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2009. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ a b "Categories and Criteria (version 3.1)". www.iucnredlist.org. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03.

- ^ BirdLife International (2013). "Anodorhynchus leari". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ BirdLife International (2017). "Anodorhynchus leari". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ a b c BirdLife International (2019). "Anodorhynchus leari". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ a b Hance, Jeremy (9 June 2009). "Lear's Macaw: back from the brink". Mongabay.com.

- ^ a b "APA Serra Branca / Raso da Catarina" (in Portuguese). INEMA: Instituto do Meio Ambiente e Recursos Hídricos (BA). Retrieved 2016-11-03.

- ^ "Top Nine Birding Destinations in 2019". BirdCalls - News and Perspectives on Bird Conservation. American Bird Conservancy. 1 February 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ "Esec Raso da Catarina" (in Portuguese). Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation. Archived from the original on 2014-06-10. Retrieved 2016-04-19.

- ^ Juniper, Tony (16 November 2004). Spix's Macaw: The Race to Save the World's Rarest Bird. Simon and Schuster. p. 55. ISBN 9780743475518.

- ^ a b "LEAR'S MACAW (Anodorhynchus leari)". World Parrot Trust. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ "AnAge entry for Anodorhynchus leari". Animal Ageing and Longevity Database. Retrieved 15 October 2021.