Indian cuisine

| This article is part of the series on |

| Indian cuisine |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of India |

|---|

|

Indian cuisine consists of a variety of regional and traditional cuisines native to the Indian subcontinent. Given the diversity in soil, climate, culture, ethnic groups, and occupations, these cuisines vary substantially and use locally available spices, herbs, vegetables, and fruits.

Indian food is also heavily influenced by religion, in particular Hinduism and Islam, cultural choices and traditions.[1][2] Historical events such as invasions, trade relations, and colonialism have played a role in introducing certain foods to India. The Columbian discovery of the New World brought a number of new vegetables and fruits. A number of these such as potatoes, tomatoes, chillies, peanuts, and guava have become staples in many regions of India.[3]

Indian cuisine has shaped the history of international relations; the spice trade between India and Europe was the primary catalyst for Europe's Age of Discovery.[4] Spices were bought from India and traded around Europe and Asia. Indian cuisine has influenced other cuisines across the world, especially those from Europe (Britain in particular), the Middle East, Southern African, East Africa, Southeast Asia, North America, Mauritius, Fiji, Oceania, and the Caribbean.[5][6]

World Wildlife Fund (WWF)’s Living Planet Report released on 10 October 2024 emphasized India’s food consumption pattern as the most sustainable among the big economies (G20 countries).[7]

History

Indian cuisine reflects an 8,000-year history of various groups and cultures interacting with the Indian subcontinent, leading to diversity of flavours and regional cuisines found in modern-day India. Later, trade with British and Portuguese influence added to the already diverse Indian cuisine.[8][9]

Prehistory and Indus Valley civilization

See also: Meluhha, Indus–Mesopotamia relations, and Indian maritime history

After 9000 BCE, a first period of indirect contacts between Fertile Crescent and Indus Valley civilizations seems to have occurred as a consequence of the Neolithic Revolution and the diffusion of agriculture. Wheat and barley were first grown around 7000 BCE, when agriculture spread from the Fertile Crescent to the Indus Valley. Sesame and humped cattle were domesticated in the local farming communities. Mehrgarh is one of the earliest sites with evidence of farming and herding in South Asia. By 3000 BCE, turmeric, cardamom, black pepper and mustard were harvested in India.

From Around 2350 BCE the evidence for imports from the Indus to Ur in Mesopotamia have been found, as well as Clove heads which are thought to originate from the Moluccas in Maritime Southeast Asia were found in a 2nd millennium BC site in Terqa. Akkadian Empire records mention timber, carnelian and ivory as being imported from Meluhha by Meluhhan ships, Meluhha being generally considered as the Mesopotamian name for the Indus Valley Civilization.

Vedic age

The ancient Hindu text Mahabharata mentions rice and vegetable cooked together, and the word "pulao" or "pallao" is used to refer to the dish in ancient Sanskrit works, such as Yājñavalkya Smṛti. Ayurveda, ancient Indian system of wellness, deals with holistic approach to the wellness, and it includes food, dhyana (meditation) and yoga.

Antiquity

Early diet in India mainly consisted of legumes, vegetables, fruits, grains, dairy products, and honey.[citation needed] Staple foods eaten today include a variety of lentils (dal), whole-wheat flour (aṭṭa), rice, and pearl millet (bājra), which has been cultivated in the Indian subcontinent since 6200 BCE.[9]

Over time, segments of the population embraced vegetarianism during the Śramaṇa movement[10][11] while an equitable climate permitted a variety of fruits, vegetables, and grains to be grown throughout the year.

A food classification system that categorised any item as saatvic, raajsic, or taamsic developed in Yoga tradition.[12][13] The Bhagavad Gita proscribes certain dietary practices (chapter 17, verses 8–10).[14]

Consumption of beef is taboo, due to cows being considered sacred in Hinduism.[15] Beef is generally not eaten by Hindus in India except for Kerala, parts of southern Tamil Nadu and the north-east.[16]

Ingredients mentioned in ancient Indian scripture

While many ancient Indian recipes have been lost in history, one can look at ancient texts to see what was eaten in ancient and pre-historic India.

- Barley[17]—(known as Yava in both Vedic and Classical Sanskrit) is mentioned many times in Rigveda and other Indian scriptures as one of the principal grains in ancient India

- Betel leaf[18]—primary use is as a wrapper for the chewing of areca nut or tobacco, where it is mainly used to add flavour; may also be used in cooking, usually raw, for its peppery taste

- Breadfruit—fritters called jeev kadge phodi in Konkani[19] or kadachakka varuthath[20] in Malayalam are a local delicacy in coastal Karnataka and Kerala

- Chickpeas[21]—popular dishes are made with chickpea flour, such as mirchi bajji and mirapakaya bajji

- Curd—a traditional yogurt or fermented milk product, originating from the Indian subcontinent, usually prepared from cow's milk, and sometimes buffalo milk, or goat milk

- Figs[17]—cultivated from Afghanistan to Portugal, also grown in Pithoragarh in the Kumaon hills of India; from the 15th century onwards, also grown in areas including Northern Europe and the New World

- Ghee—a class of clarified butter that originated in ancient India, commonly used in the Indian subcontinent, Middle-Eastern cuisine, traditional medicine, and religious rituals

- Grape wine[22]—first-known mention of grape-based wines in India is from the late 4th-century BC writings of Chanakya

- Honey[23]—the spiritual and supposed therapeutic use of honey in ancient India was documented in both the Vedas and the Ayurveda texts

- Mango—the Jain goddess Ambika is traditionally represented as sitting under a mango tree

- Mustard[17]—brown mustard is a spice that was cultivated in the Indus Valley civilization and is one of the important spices used in the Indian subcontinent today

- Pomegranate—in some Hindu traditions, the pomegranate (Hindi: anār) symbolizes prosperity and fertility, and is associated with both Bhoomidevi (the earth goddess) and Lord Ganesha (the one fond of the many-seeded fruit)

- Rice—cultivated in the Indian subcontinent from as early as 5,000 BC

- Rice cake—quite a variety are available[24]

- Rose apple—mainly eaten as a fruit and also used to make pickles (chambakka achar)

- Saffron[25]—almost all saffron grows in a belt from Spain in the west to Kashmir in the east

- Salt[25]—considered to be a very auspicious substance in Hinduism and is used in particular religious ceremonies like house-warmings and weddings; in Jainism, devotees lay an offering of raw rice with a pinch of salt before a deity to signify their devotion, and salt is sprinkled on a person's cremated remains before the ashes are buried

- Sesame oil[25]—popular in Asia, especially in Korea, China, and the South Indian states of Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu, where its widespread use is similar to that of olive oil in the Mediterranean

- Sorghum[21]—commonly called jwaarie, jowar, jola, or jondhalaa, sorghum is one of the staple sources of nutrition

- Sugar—produced in the Indian subcontinent since ancient times, its cultivation spread from there into modern-day Afghanistan through the Khyber Pass

- Sugarcane[21]—the earliest known production of crystalline sugar began in northern India; the earliest evidence of sugar production comes from ancient Sanskrit and Pali texts

- Turmeric[22]—used widely as a spice in South Asian and Middle Eastern cooking

Middle Ages to the 16th century

During the Middle Ages, several Indian dynasties were predominant, including the Gupta dynasty. Travel to India during this time introduced new cooking methods and products to the region, including tea.[citation needed]

India was later invaded by tribes from Central Asian cultures, which led to the emergence of Mughlai cuisine, a mix of Indian and Central Asian cuisine. Hallmarks include seasonings such as saffron.[26]

Colonial Period

The Portuguese and British during their rule introduced cooking techniques such as baking, and foods from the New World and Europe. The new-world vegetables popular in cuisine from the Indian subcontinent include maize, tomato, potato, sweet potatoes, peanuts, squash, and chilli. Most New World vegetables such as sweet potatoes, potatoes, Amaranth, peanuts and cassava based Sago are allowed on Hindu fasting days. Cauliflower was introduced by the British in 1822.[27] In the late 18th/early 19th century, an autobiography of a Scottish Robert Lindsay mentions a Sylheti man called Saeed Ullah cooking a curry for Lindsay's family. This is possibly the oldest record of Indian cuisine in the United Kingdom.[28][29]

-

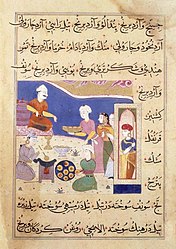

Bhang eaters in India c. 1790. Bhang is an edible preparation of cannabis native to the Indian subcontinent. It was used by Hindus in food and drink as early as 1000 BCE.[30]

-

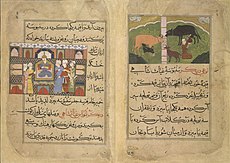

A page from the Nimatnama-i-Nasiruddin-Shahi, book of delicacies and recipes. It documents the fine art of making kheer.

-

Medieval Indian Manuscript Nimatnama-i-Nasiruddin-Shahi (circa 16th century) showing samosas being served.

Ingredients

Staple foods of Indian cuisine include pearl millet (bājra), rice, whole-wheat flour (aṭṭa), and a variety of lentils, such as masoor (most often red lentils), tuer (pigeon peas), urad (black gram), and moong (mung beans). Lentils may be used whole, dehusked—for example, dhuli moong or dhuli urad—or split. Split lentils, or dal, are used extensively.[31] Some pulses, such as channa or cholae (chickpeas), rajma (kidney beans), and lobiya (black-eyed peas) are very common, especially in the northern regions. Channa and moong are also processed into flour (besan).

Many Indian dishes are cooked in vegetable oil, but peanut oil is popular in northern and western India, mustard oil in eastern India,[26] and coconut oil along the western coast, especially in Kerala and parts of southern Tamil Nadu.[32][self-published source?] Gingelly (sesame) oil is common in the south since it imparts a fragrant, nutty aroma.[33]

In recent decades, sunflower, safflower, cottonseed, and soybean oils have become popular across India.[34] Hydrogenated vegetable oil, known as Vanaspati ghee, is another popular cooking medium.[35] Butter-based ghee, or deshi ghee, is used commonly.

Many types of meat are used for Indian cooking, but chicken and mutton tend to be the most commonly consumed meats. Fish and beef consumption are prevalent in some parts of India, but they are not widely consumed except for coastal areas, as well as the north east.[citation needed]

The most important and frequently used spices and flavourings in Indian cuisine are whole or powdered chilli pepper (mirch, introduced by the Portuguese from Mexico in the 16th century), black mustard seed (sarso), cardamom (elaichi), cumin (jeera), turmeric (haldi), asafoetida (hing), ginger (adrak), coriander (dhania), and garlic (lasoon).[36]

One popular spice mix is garam masala, a powder that typically includes seven dried spices in a particular ratio, including black cardamom, cinnamon (dalchini), clove (laung), cumin (jeera), black peppercorns, coriander seeds and anise star.[37][self-published source?]. Each culinary region has a distinctive garam masala blend—individual chefs may also have their own.

The spices chosen for a dish are freshly ground and then fried in hot oil or ghee to create a paste. The process is called bhuna, the name also being used for a type of curry.[38]

There are other spice blends which are popular in various regions. Panch phoron is a spice blend which is popular in eastern India. Goda masala is a sweet spice mix which is popular in Maharashtra. Some leaves commonly used for flavouring include bay leaves (tejpat), coriander leaves, fenugreek (methi) leaves, and mint leaves. The use of curry leaves and roots for flavouring is typical of Gujarati[39] and South Indian cuisine.[40] Sweet dishes are often seasoned with cardamom, saffron, nutmeg, and rose petal essences.

Regional cuisines

Cuisine differs across India's diverse regions as a result of variation in local culture, geographical location (proximity to sea, desert, or mountains), and economics. It also varies seasonally, depending on which fruits and vegetables are ripe.

Andaman and Nicobar Islands

Seafood plays a major role in the cuisine of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.[41] Staples of the diet of the Indigenous Andamanese traditionally include roots, honey, fruits, meat, and fish, obtained by hunting and gathering. Some insects were also eaten as delicacies.[42] Immigration from mainland of India, however, has resulted in variations in the cuisine.

Andhra Pradesh

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2020) |

The cuisine of Andhra Pradesh belongs to the two Telugu-speaking regions of Rayalaseema and Coastal Andhra and is part of Telugu cuisine. The food of Andhra Pradesh is known for its heavy use of spices, and the use of tamarind.

Seafood is common in the coastal region of the state. Rice is the staple food (as is with all South Indian states) eaten with lentil preparations such as pappu (lentils) and pulusu (stew) and spicy vegetables or curries.

In Andhra, leafy greens or vegetables such as bottle-gourd and eggplant are usually added to dal. Pickles are an essential part of the local cuisine; popular among those are mango-based pickles such as avakaya and maagaya, gongura (a pickle made from sorrel leaves),[43] usirikaya (gooseberry or amla), nimmakaya (lime), and tomato pickle.

Perugu (yogurt) is a common addition to meals, as a way of tempering spiciness. Breakfast items include dosa, pesarattu (mung bean dosa), vada, and idli.

Arunachal Pradesh

The staple food of Arunachal Pradesh is rice, along with fish, meat, and leaf vegetables.[44] Native tribes of Arunachal are meat eaters and use fish, eggs, beef, chicken, pork, and mutton to make their dishes.

Many varieties of rice are used. Boiled rice cakes wrapped in leaves are a popular snack. Thukpa is a kind of noodle soup common among the Monpa tribe of the region.[45]

Lettuce is the most common vegetable, usually prepared by boiling with ginger, coriander, and green chillies.[46]

Apong or rice beer made from fermented rice or millet is a popular beverage in Arunachal Pradesh and is consumed as a refreshing drink.[47]

Assam

Assamese cuisine is a mixture of different indigenous styles, with considerable regional variation and some external influences. Although it is known for its limited use of spices,[48] Assamese cuisine has strong flavours from its use of endemic herbs, fruits, and vegetables served fresh, dried, or fermented.

Rice is the staple food item and a huge variety of endemic rice varieties, including several varieties of sticky rice are a part of the cuisine in Assam. Fish, generally freshwater varieties, are widely eaten. Other non-vegetarian items include chicken, duck, squab, snails, silkworms, insects, goat, pork, venison, turtle, monitor lizard, etc.

The region's cuisine involves simple cooking processes, mostly barbecuing, steaming, or boiling. Spices are not fried before use in the cuisine of Assam.

A traditional meal in Assam begins with a khar, a class of dishes named after the main ingredient and ends with a tenga, a sour dish. Homebrewed rice beer or rice wine is served before a meal. The food is usually served in bell metal utensils.[49] Paan, the practice of chewing betel nut, generally concludes a meal.[50]

West Bengal

Mughal cuisine is a universal influencer in the Bengali palate, and has introduced Persian and Islamic foods to the region, as well as a number of more elaborate methods of preparing food, like marination using ghee. Fish, meat (chicken, goat meat), egg, rice, milk, and sugar all play crucial parts in Bengali cuisine.[51]

Bengali cuisine can be subdivided into four different types of dishes, charbya (চারব্য), or food that is chewed, such as rice or fish; choṣya, or food that is sucked, such as ambal and tak; lehya (লেহ্য), or foods that are meant to be licked, like chuttney; and peya (পেয়ে), which includes drinks, mainly milk.[52]

During the 19th century, many Odia-speaking cooks were employed in Bengal,[53] which led to the transfer of several food items between the two regions. Bengali cuisine is the only traditionally developed multi-course tradition from the Indian subcontinent that is analogous in structure to the modern service à la russe style of French cuisine, with food served course-wise rather than all at once.[54]

Bengali cuisine differs according to regional tastes, such as the emphasis on the use of chilli pepper in the Chittagong district of Bangladesh[55] However, across all its varieties, there is predominant use of mustard oil along with large amounts of spices.

The cuisine is known for subtle flavours with an emphasis on fish, meat, vegetables, lentils, and rice.[56] Bread is also a common dish in Bengali cuisine, particularly a deep-fried version called luchi is popular. Fresh aquatic fish is one of its most distinctive features; Bengalis prepare fish in many ways, such as steaming, braising, or stewing in vegetables and sauces based on coconut milk or mustard.

East Bengali food, which has a high presence in West Bengal and Bangladesh, is much spicier than the West Bengali cuisine, and tends to use high amounts of chilli, and is one of the spiciest cuisines in India and the World.

Shondesh and Rashogolla are popular dishes made of sweetened, finely ground fresh cheese. For the latter, West Bengal and neighboring Odisha both claim to be the origin of dessert. Each state also has a geographical indication for their regional variety of rasgulla.[57][58]

The cuisine is also found in the state of Tripura and the Barak Valley of Assam.

Bihar

Bihari cuisine may include litti chokha,[59] a baked salted wheat-flour cake filled with sattu (baked chickpea flour) and some special spices, which is served with baigan bharta,[60] made of roasted eggplant (brinjal) and tomatoes.[61][62]

Among meat dishes, meat saalan[63] is a popular dish made of mutton or goat curry with cubed potatoes in garam masala.

Dalpuri is another popular dish in Bihar. It is salted wheat-flour bread, filled with boiled, crushed, and fried gram pulses.[64]

Malpua is a popular sweet dish of Bihar, prepared by a mixture of maida, milk, bananas, cashew nuts, peanuts, raisins, sugar, water, and green cardamom. Another notable sweet dish of Bihar is balushahi, which is prepared by a specially treated combination of maida and sugar along with ghee, and the other worldwide famous sweet, khaja is made from flour, vegetable fat, and sugar, which is mainly used in weddings and other occasions. Silao near Nalanda is famous for its production.

During the festival of Chhath, thekua, a sweet dish made of ghee, jaggery, and whole-meal flour, flavoured with aniseed, is made.[61]

Other food items that are quite prominent in Bihar are, Pittha, Aaloo Bhujiya, Reshmi Kebab, Palwal ki mithai, and Puri Sabzi.[65]

Chandigarh

Chandigarh, the capital of Punjab and Haryana is a city of 20th-century origin with a cosmopolitan food culture mainly involving North Indian cuisine. People enjoy home-made recipes such as paratha, especially at breakfast, and other Punjabi foods like roti which is made from wheat, sweetcorn, or other glutenous flour with cooked vegetables or beans. Sarson da saag and dal makhani are well-known dishes among others.[66] Popular snacks include gol gappa (known as panipuri in other places). It consists of a round, hollow puri, fried crisp and filled with a mixture of flavoured water, boiled and cubed potatoes, bengal gram beans, etc.

Chhattisgarh

Chhattisgarh cuisine is unique in nature and not found in the rest of India, although the staple food is rice, like in much of the country. Many Chhattisgarhi people drink liquor brewed from the mahuwa flower palm wine (tadi in rural areas).[67] Chhattisgarhi cuisines varies as per special occasions and festivals like Thethari and Khurmi, fara, gulgule bhajiya, chausela, chila, aaersa are prepared in regional festivals.[68] The tribal people of the Bastar region of Chhattisgarh eat ancestral dishes such as mushrooms, bamboo pickle, bamboo vegetables, etc.[69][70]

Dadra and Nagar Haveli

The local cuisine resembles the cuisine of Gujarat. Ubadiyu[71] is a local delicacy made of vegetables and beans with herbs. The common foods include rice, roti, vegetables, river fish, and crab. People also enjoy buttermilk and chutney made of different fruits and herbs.[72]

Daman and Diu

Daman and Diu is a union territory of India which, like Goa, was a former colonial possession of Portugal. Consequently, both native Gujarati food and traditional Portuguese food are common. Being a coastal region, the communities are mainly dependent on seafood. Normally, rotli and tea are taken for breakfast, rotla and saak for lunch, and chokha along with saak and curry are taken for dinner. Some of the dishes prepared on festive occasions include puri, lapsee, potaya, dudh-plag, and dhakanu.[73] While alcohol is prohibited in the neighbouring state of Gujarat, drinking is common in Daman and Diu. Better known as the "pub" of Gujarat. All popular brands of alcohol are readily available.

Delhi

Delhi was once the capital of the Mughal empire, and it became the birthplace of Mughlai cuisine. Delhi is noted for its street food. The Paranthewali Gali in Chandani Chowk is just one of the culinary landmarks for stuffed flatbread (parathas).

Delhi has people from different parts of India, thus the city has different types of food traditions; its cuisine is influenced by the various cultures. Punjabi cuisine is common, due to the dominance of Punjabi communities.[74]

Delhi cuisine is actually an amalgam of different Indian cuisines modified in unique ways. This is apparent in the different types of street food available. Kababs, kachauri, chaat, Indian sweets, Indian ice cream (commonly called kulfi), and even Western food items like sandwiches and patties, are prepared in a style unique to Delhi and are quite popular.[75]

Goa

The area has a tropical climate, which means the spices and flavours are intense. Use of kokum is a distinct feature of the region's cuisine.

Goan cuisine is mostly seafood and meat-based; the staple foods are rice and fish. Kingfish (vison or visvan) is the most common delicacy, and others include pomfret, shark, tuna, and mackerel; these are often served with coconut milk.[76] Shellfish, including crabs, prawns, tiger prawns, lobster, squid, and mussels, are commonly eaten.

The cuisine of Goa is influenced by its Hindu origins, 400 years of Portuguese colonialism, and modern techniques.[76][77]

Bread, introduced by the Portuguese, is very popular, and is an important part of the Goan breakfast, most frequently in the form of toast.

Gujarat

Gujarati cuisine is primarily vegetarian. The typical Gujarati thali consists of roti (rotlii in Gujarati), daal or kadhi, rice, sabzi/shaak, papad and chaas (buttermilk).

Sabzi is a dish of different combinations of vegetables and spices which may be stir fried, spicy or sweet.[78] Gujarati cuisine can vary widely in flavour and heat based on personal and regional tastes. North Gujarat, Kathiawad, Kachchh, and South Gujarat are the four major regions of Gujarati cuisine.[79]

Many Gujarati dishes are simultaneously sweet, salty (like handvo), and spicy. In mango season, keri no ras (fresh mango pulp) is often an integral part of the meal. Spices also vary seasonally. For example, garam masala is used much less in summer.

Gujarati snacks include sev khamani,[80] khakhra, dal vada,[81] methi na bhajiya,[82] khaman, bhakharwadi and more.

Regular fasting, with diets limited to milk, dried fruit, and nuts, is a common practice,[83]

Haryana

Cattle being common in Haryana, dairy products are a common component of its cuisine.[84][85]

Specific regional dishes include kadhi, pakora, besan masala roti,[86] bajra aloo roti,[87] churma, kheer, bathua raita,[88] methi gajar,[89] singri ki sabzi,[90] and tomato chutney.

In the past, its staple diet included bajra khichdi,[91] rabdi, onion chutney,[92] and bajra ki roti.[93] In non-vegetarian cuisine it includes kukad kadhai[94] and chicken tikka masala.

Lassi, sharbat, nimbu pani and labsi (a mixture of bajra flour and lassi) are three popular non-alcoholic beverages in Haryana. However, liquor stores are common there, which cater to a large number of truck drivers.[95]

Himachal Pradesh

The daily diet of Himachal people is similar to that of the rest of North India, including lentils, broth, rice, vegetables, and bread, although non-vegetarian cuisine is preferred. Some of the specialities of Himachal include sidu,[96] patande,[97] chukh, rajmah, and til chutney.[98]

Jammu and Kashmir

The cuisine of Jammu and Kashmir is from two regions of the state: Jammu division and Kashmir Valley. Kashmiri cuisine has evolved over hundreds of years. Its first major influence was the food of the Kashmiri Hindus and Buddhists.

The cuisine was later influenced by the cultures which arrived with the invasion of Kashmir by Timur from the area of modern Uzbekistan. Subsequent influences have included the cuisines of Central Asia and the North Indian plains.

The most notable ingredient in Kashmiri cuisine is mutton, of which over 30 varieties are known.[99] Wazwan is a multicourse meal in the Kashmiri tradition, the preparation of which is considered an art.[100]

Kashmiri pandit food is elaborate, and an important part of the Pandits' ethnic identity. Kashmiri pandit cuisine usually uses dahi (yogurt), oil, and spices such as turmeric, red chilli, cumin, ginger, and fennel, though they do not use onion and garlic.[101] Birayanis are quite popular, and are the speciality of Kashmir.

The Jammu region is famous for its sund panjeeri, patisa, rajma with rice and Kalari cheese.

Dogri food includes ambal (sour pumpkin dish),[102] khatta meat,[103] kulthein di dal,[104] dal chawal,[105] maa da madra (black gram lentils in yogurt)[106] and Uriya.

Many types of pickles are made including mango, kasrod, and girgle. Street food is also famous which include various types of chaats, specially gol gappas, gulgule, chole bhature, rajma kulcha[107] and dahi bhalla.

Jharkhand

Staple foods in Jharkhand are rice, dal and vegetables. Famous dishes include chirka roti,[108] pittha, malpua, dhuska, arsa roti[109] and litti chokha.[110]

Local alcoholic drinks include handia, a rice beer, and mahua daru, made from flowers of the mahua tree (Madhuca longifolia).[111][112]

Karnataka

A number of dishes, such as idli, rava idli, Mysore masala dosa, etc., were invented here and have become popular beyond the state of Karnataka[citation needed]. Equally, varieties in the cuisine of Karnataka have similarities with its three neighbouring South Indian states, as well as the states of Maharashtra and Goa to its north. It is very common for the food to be served on a banana leaf, especially during festivals and functions.

Karnataka cuisine can be very broadly divided into Mysore/Bangalore cuisine, North Karnataka cuisine, Udupi cuisine, Kodagu/Coorg cuisine, Karavali/coastal cuisine, and Saraswat cuisine.

This cuisine covers a wide spectrum of food from pure vegetarian and vegan to meats like pork, and from savouries to sweets.

Typical dishes include bisi bele bath, jolada rotti, badanekai yennegai,[113] holige, kadubu, chapati, idli vada, ragi rotti, akki rotti, saaru, huli, kootu, vangibath, khara bath, kesari bhath, sajjige, neer dosa, mysoore[clarification needed], haal bai,[114] chiroti, benne dose, majjige huli, ragi mudde, and uppittu.

The Kodagu district is known for spicy pork curries,[115] while coastal Karnataka specialises in seafood. Although the ingredients differ regionally, a typical Kannadiga oota (Kannadiga meal) is served on a banana leaf. The coastal districts of Dakshina Kannada and Udupi have slightly varying cuisines, which make extensive use of coconut in curries and frequently include seafood.[116][117]

Kerala

Contemporary Kerala food includes vegetarian and non-vegetarian dishes. Fish and seafood play a major role in Kerala cuisine, as Kerala is a coastal state. An everyday Kerala meal in most households consists of rice with fish curry made of sardines, mackerel, seer fish, king fish, pomfret, prawns, shrimp, sole, anchovy, or parrotfish, (mussels, oysters, crabs, squid, scallops are not rare), and vegetable curry and stir-fried vegetables with or without coconut traditionally known as thoran or mizhukkupiratti. As Kerala has large number of inland water bodies, freshwater fish are also abundant, and part of regular meals. It is common in Kerala to have a breakfast with non-vegetarian dishes in restaurants, in contrast to other states in India. Chicken or mutton stews, lamb, chicken, beef, pork, egg curry, and fish curry with tapioca for breakfast are also widely enjoyed.

Kerala cuisine reflects its rich trading heritage. Over time, various cuisines have blended with indigenous dishes, while foreign ones have been adapted to local tastes.[118] Significant Arab, Syrian, Portuguese, Dutch, Jewish, and Middle Eastern influences exist in this region's cuisine.

Coconuts grow in abundance in Kerala, so grated coconut and coconut milk are commonly used for thickening and flavouring.[119] Kerala's long coastline and numerous rivers have led to a strong fishing industry in the state, making seafood a common part of the meal. Starchy food like Rice and tapioca forms the major part of Kerala's staple food.[120] Having been a major region of spice cultivation and trade for thousands of years, the spices like black pepper, cardamom, clove, ginger, cumin and cinnamon finds extensive use in Kerala cuisine. Kerala sadhya, an elaborate vegetarian banquet prepared for festivals and ceremonies. A full-course sadhya, which consists of rice with about 20 different accompaniments and desserts is the ceremonial meal, eaten usually on celebrations such as marriages, Onam, Vishu, etc. and is served on a plantain leaf.

Most of Kerala's Hindus, except its Brahmin community, eats fish, chicken, beef, pork, eggs, and mutton.[121] The Brahmin are famed for their vegan cuisine, especially varieties of sambar and rasam. A thick vegetable stew popular in South and Central India called avial is believed to have originated in southern Kerala. The avial, eaten widely in the state, is an important vegetarian dish in Kerala sadya. In most Kerala households, a typical meal consists of rice served along with vegetables and fish or meat dishes. Kerala also has a variety of breakfast dishes like idli, dosa, appam, idiyappam, puttu, parotta and pathiri served with sambar, coconut chutney, mutta curry (egg curry), kadala (chickpea) curry, green peas, chicken curry, beef curry and mutton curry.[122]

The Muslim community of Kerala blend Arabian, North Indian, and indigenous Malabari cuisines, using chicken, eggs, beef, and mutton.[123] Thalassery biryani is the only biryani variant, which is of Kerala origin having originated in Talassery, in Malabar region. The dish is significantly different from other biryani variants.[124] Snacks like Pazham nirachathu, Unnakkai, Bread pola— made of bread, eggs, milk and a simple masala, Iftar preparations like Thari kanji, Kozhi pichuporichathu (shredded chicken), Pidi— a preparation of rice dumplings dunked in gravy,Irachi pathiri, Chatti pathiri, Meen pathiri, Neriya pathiri and Kannu vecha pathiri – roti varieties usually made of powdered rice, dishes like Kaai curry etc., are also contributions of Muslim community to the broad Kerala cuisine.[125] The Pathanamthitta region is known for raalan and fish curries. Appam along with wine and curries of duck, pork and cured beef are popular among Syrian Christians in Central Kerala.

Popular desserts are payasam (pudding) and halwa. Payasam, especially Ambalappuzha Paalpayasam also known as Gopala Kashayam (Krishnan's potion) prepared at the 17th century Ambalappuzha Sri Krishna swami temple, is a delicacy known for its unique and flavourful taste. Interestingly, on each day the paalpayasam is prepared only after (ritualistically) seeking due permission from the presiding deity – Shri Krishna.[126] Kerala has a number of paayasam varieties including but not limited to Paalpayasam, Vermicelli Payasam, Pradhaman, Ada Pradhaman, Chakka (Jackfruit) Pradhaman, Parippu Paayasam and more. Paayasam like Vermicelli Payasam (Semiya payasam) also finds a place in Iftar feast of Muslim communities in Kerala.

Halva is one of the most commonly found or easily recognized sweets in bakeries throughout Kerala, and originated from the Gujarathi community in Calicut.[127] Europeans used to call the dish "sweetmeat" due to its texture, and a street in Kozhikode where became named Sweet Meat Street during colonial rule. This is mostly made from maida (highly refined wheat), and comes in various flavours, such as banana, ghee or coconut. However, karutha haluva (black haluva) made from rice is also very popular.

Ladakh

Ladakhi cuisine is from the two districts of Leh and Kargil in the union territory of Ladakh. Ladakhi food has much in common with Tibetan food, the most prominent foods being thukpa (noodle soup) and tsampa, known in Ladakhi as ngampe (roasted barley flour). Edible without cooking, tsampa makes useful trekking food.

Strictly Ladakhi dishes include skyu and chutagi, both heavy and rich soup pasta dishes, skyu being made with root vegetables and meat, and chutagi with leafy greens and vegetables.[128] As Ladakh moves toward a cash-based economy, foods from the plains of India are becoming more common.[129]

As in other parts of Central Asia, tea in Ladakh is traditionally made with strong green tea, butter, and salt. It is mixed in a large churn and known as gurgur cha, after the sound it makes when mixed. Sweet tea (cha ngarmo) is common now, made in the Indian style with milk and sugar. Most of the surplus barley that is produced is fermented into chang, an alcoholic beverage drunk especially on festive occasions.[130]

Lakshadweep

The cuisine of Lakshadweep prominently features seafood and coconut. Local food consists of spicy non-vegetarian and vegetarian dishes.

The culinary influence of Kerala is quite evident in the cuisines of Lakshadweep, since the island lies in close proximity to Kerala. Coconut and sea fish serve as the foundation of most meals.

The people of Lakshadweep drink large amounts of coconut water, which is the most abundant aerated drink on the island. Coconut milk is the base for most of the curries. All the sweet or savory dishes have a touch of famous Malabar spices. Local people also prefer to have dosa, idlis, and various rice dishes.[131]

Madhya Pradesh

The cuisine in Madhya Pradesh varies regionally. Wheat and meat are common in the north and west of the state, while the wetter south and east are dominated by rice and fish. Milk is a common ingredient in Gwalior and Indore.

The street food of Indore is well known, with shops that have been active for generations.[132] Bhopal is known for meat and fish dishes such as rogan josh, korma, qeema, biryani, pilaf, and kebabs. On a street named Chatori Gali in old Bhopal, one can find traditional Muslim nonvegetarian fare such as paya soup, bun kabab, and nalli-nihari as some of the specialties.[133]

Dal bafla is a common meal in the region and can be easily found in Indore and other nearby regions, consisting of a steamed and grilled wheat cake dunked in rich ghee, which is eaten with daal and ladoos.

The culinary specialty of the Malwa and Indore regions of central Madhya Pradesh is poha (flattened rice); usually eaten at breakfast with jalebi.[134]

Beverages in the region include lassi, beer, rum and sugarcane juice. A local liquor is distilled from the flowers of the mahua tree. Date palm toddy is also popular. In tribal regions, a popular drink is the sap of the sulfi tree, which may be alcoholic if it has fermented.

Maharashtra

Maharashtrian cuisine is an extensive balance of many different tastes. It includes a range of dishes from mild to very spicy tastes. Bajri, wheat, rice, jowar, vegetables, lentils, and fruit form important components of the Maharashtrian diet.

Popular dishes include puran poli, ukdiche modak, batata wada, sabudana khichdi, masala bhat,[135] pav bhaji, and wada pav.[136] Poha or flattened rice is also usually eaten at breakfast. Kanda poha[137] and aloo poha[138] are some of the dishes cooked for breakfast and snacking in evenings.

Popular spicy meat dishes include those that originated in the Kolhapur region. These are the Kolhapuri Sukka mutton,[139] pandhra rassa,[140] and tabmda rassa.[141] Shrikhand, a sweet dish made from strained yogurt, is a main dessert of Maharashtrian cuisine.[142]

The cuisine of Maharashtra can be divided into two major sections, the coastal and the interior. The Konkan, on the coast of the Arabian Sea, has its own type of cuisine, a homogeneous combination of Malvani, Goud Saraswat Brahmin, and Goan cuisine. In the interior of Maharashtra, the Paschim Maharashtra, Khandesh, Vidarbha and Marathwada areas have their own distinct cuisines.

The cuisine of Vidarbha uses groundnuts, poppy seeds, jaggery, wheat, jowar, and bajra extensively. A typical meal consists of rice, roti, poli, or bhakar, along with varan and aamtee[143]—lentils and spiced vegetables. Cooking is common with different types of oil.

Savji food from Vidarbha is well known all over Maharashtra. Savji dishes are very spicy and oily. Savji mutton curries are very famous.

Like other coastal states, an enormous variety of vegetables, fish, and coconuts exists, where they are common ingredients. Peanuts and cashews are often served with vegetables. Grated coconuts are used to flavour many types of dishes, but coconut oil is not widely used; peanut oil is preferred.[144]

Kokum, most commonly served chilled, in an appetiser-digestive called sol kadhi, is prevalent. During summer, Maharashtrians consume panha, a drink made from raw mango.[145][146]

Malwani

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2021) |

Malwani cuisine is a specialty of the tropical area which spans from the shore of Deogad Malwan to the southern Maharashtrian border with Goa. The unique taste and flavor of Malwani cuisine comes from Malwani masala and use of coconut and kokam.

The staple foods are rice and fish. Various kinds of red and green fish, prawns, crab, and shellfish curries (also called mashacha sar in the Malwani language) are well known, along with kombadi (chicken) wade and mutton prepared Malwani style. Mohari mutton is also one of the distinct delicacies of Malwani cuisine.

A large variety of fish is available in the region, which include surmai, karali, bangada, bombil (Bombay duck), paplet (pomfret), halwa, tarali, suandale, kolambi (prawns), tisari (shellfish), kalwa (stone fish) and kurli (crab).

All these fish are available in dried form, including prawns, which are known as sode. Local curries and chatanis are also prepared with dried fish.

Different types of rice breads and pancakes add to the variety of Malwani cuisine and include tandlachi bhakari,[147] ghawane, amboli,[148] patole, appe, tandalachi and shavai (rice noodles). These rice breads can be eaten specially flavored with coconut milk, fish curries, and chicken or mutton curries.

Sole kadi made from kokam and coconut milk is a signature appetizer drink . For vegetarians, Malwani delicacies include alloochi bhaji, alloochi gathaya, kalaya watanyacha, and sambara (black gram stew).

The sweets and desserts include ukadiche modak,[149] Malawani khaje, khadakahde kundiche ladu, shegdanyache ladu, tandalchi kheer, and tandalachi shavai ani ras (specially flavored with coconut milk).

Manipur

Manipuri cuisine is represented by the cuisine of the Meitei people who form the majority population in the central plain. Meitei food are simple, tasty, organic and healthy. Rice with local seasonal vegetables and fish form the main diet.

Most of the dishes are cooked like vegetable stew, flavored with either fermented fish called ngari, or dried and smoked fish.

The most popular Manipuri dish is eromba, a preparation of boiled and mashed vegetables, often including carrots, potatoes or beans, mixed with chilli and roasted fermented fish.

Another popular dish is the savory cake called paknam, made of a lentil flour stuffed with various ingredients such as banana inflorescence, mushrooms, fish, vegetables etc., and baked covered in turmeric leaves.

Along with spicy dishes, a mild side dish of steamed or boiled sweet vegetables are often served in the daily meals. The Manipuri salad dish called singju, made of finely julienned cabbage, green papaya, and other vegetables, and garnished with local herbs, toasted sesame powder and lentil flour is extremely popular locally, and often found sold in small street side vendors.

Singju is often served with bora, which are fritters of various kinds, and also kanghou, or oil-fried spicy veggies.[150] Cooked and fermented soybean is a popular condiment in all Manipuri kitchens.

The staple diet of Manipur consists of rice, fish, large varieties of leafy vegetables (of both aquatic and terrestrial). Manipuris typically raise vegetables in a kitchen garden and rear fishes in small ponds around their house. Since the vegetables are either grown at home or obtained from local market, the cuisines are very seasonal, each season having its own special vegetables and preparations.

The taste is very different from mainland Indian cuisines because of the use of various aromatic herbs and roots that are peculiar to the region. They are however very similar to the cuisines of Southeast, East, and Central Asia, Siberia, Micronesia and Polynesia.

Meghalaya

Meghalayan cuisine is unique and different from other Northeastern Indian states.[151] Spiced meat is common, from goats, pigs, fowl, ducks, chickens, and cows. In the Khasi and Jaintia Hills districts, common foods include jadoh, ki kpu, tung-rymbai,[152] and pickled bamboo shoots.

Other common foods in Meghalaya include minil songa (steamed sticky rice) and sakkin gata.

Like other tribes in the northeast, the Garos ferment rice beer, which they consume in religious rites and secular celebrations.[153]

Mizoram

The cuisine of Mizoram differs from that of most of India, though it shares characteristics to other regions of Northeast India and North India.

Rice is the staple food of Mizoram, while Mizos love to add non-vegetarian ingredients in every dish. Fish, chicken, pork and beef are popular meats among Mizos. Dishes are served on fresh banana leaves. Most of the dishes are cooked in mustard oil.

Meals tend to be less spicy than in most of India. Mizos love eating boiled vegetables along with rice. A popular dish is bai, made from boiling vegetables (spinach, eggplant, beans, and other leafy vegetables) with bekang (fermented soya beans) or sa-um, fermented pork fat served with rice. Sawhchiar is another common dish, made of rice and cooked with pork or chicken.[154][155]

Nagaland

The cuisine of Nagaland reflects that of the Naga people. It is known for exotic pork meats cooked with simple and flavourful ingredients,[156] like the extremely hot bhut jolokia (ghost chili) pepper, fermented bamboo shoots, and akhuni (fermented soya beans). Another unique and strong ingredient used by the Naga people, is the fermented fish known as ngari.

Fresh herbs and other local greens also feature prominently in the Naga cuisine. The Naga use oil sparingly, preferring to ferment, dry, and smoke their meats and fish.

Traditional homes in Nagaland have external kitchens that serve as smokehouses.[157]

A typical meal consists of rice, meat, a chutney, a couple of stewed or steamed vegetable dishes, flavored with ngari or akhuni. Desserts usually consist of fresh fruits.

Odisha

The cuisine of Odisha relies heavily on local ingredients. Flavours are usually subtle and delicately spiced. Fish and other seafood, such as crab and shrimp, are very popular, and chicken and mutton are also consumed.

Pakhala, a dish made of rice, water, and dahi (yogurt), that is fermented overnight, is very popular in summer in rural areas.[158] Odias are very fond of sweets, so dessert follows most meals.

Panch phutana, a mix of cumin, mustard, fennel, fenugreek and kalonji (nigella), is widely used for flavouring vegetables and dals,[159] while garam masala and turmeric are commonly used for meat-based curries.

Popular Odia dishes include arna, kanika, dalma, khata (tamato and oou), dali (different types of lentils, i.e. harada [red gram], muga [green gram], kolatha [horsegram], etc.), spinach and other green leaves, and alu-bharta (mashed potato)[160] along with pakhala.

Odisha and neighboring West Bengal both claim to be the origin of rasgulla, each state having a geographical indication for their regional variety of the dessert.[57][58] Odisha is also known for its chhena- based sweets, including chhena poda, chhena gaja, chhena jhili, and rasabali.

Puducherry

The union territory of Puducherry was a French colony for around 200 years, making French cuisine a strong influence on the area. Tamil cuisine is eaten by the territory's Tamil majority. The influence of the neighbouring areas, such as Andhra Pradesh and Kerala, is also visible on the territory's cuisine.

Some favourite dishes include coconut curry, tandoori potato, soya dosa, podanlangkai (snake gourd chutney),[161] curried vegetables, stuffed cabbage, and baked beans.[162]

Punjab

The cuisine of Punjab is known for its diverse range of dishes. It is closely related to the cuisine of the neighbouring Punjab province of Pakistan.

The state, being an agriculture center, is abundant with whole grains, vegetables, and fruits. Home-cooked and restaurant Punjabi cuisine can vary significantly.

Restaurant-style Punjabi cooking puts emphasis on creamy textured foods by using ghee, butter and cream, while home-cooked meals center around whole wheat, rice, and other ingredients flavored with various kinds of masalas.[163]

Common dishes cooked at home are roti with daal and dahi (yogurt) with a side chutney and salad that includes raw onion, tomato, cucumber, etc.

The meals are also abundant of local and seasonal vegetables usually sautéed with spices such as cumin, dried coriander, red chili powder, turmeric, black cloves, etc. Masala chai is a favorite drink and is consumed in everyday life and at special occasions.

Many regional differences exist in the Punjabi cuisine based on traditional variations in cooking similar dishes, food combinations, preference of spice combination, etc. It is clear that "the food is simple, robust, and closely linked to the land."[164]

Certain dishes exclusive to Punjab, such as makki di roti and sarson da saag,[165] dal makhani, and others are a favorite of many.

The masala in a Punjabi dish traditionally consists of onion, garlic, ginger, cumin, garam masala, salt, turmeric, tomatoes sauteed in mustard oil. Tandoori food is a Punjabi specialty. Dishes like Bhatti da murgh also known as tandoori chicken, Chicken hariyali kabab, Achari paneer tikka, fish ajwaini tikka and Amritsari kulcha are some popular tandoori foods from Punjab.

Common meat dishes in this region are Bhakra curry (goat) and fish dishes.[166] Dairy products are regularly enjoyed and usually accompany main meals in the form of dahi, milk, and milk-derived products such as lassi, paneer, and more.

Punjab has a large number of people following the Sikh religion who traditionally follow a vegetarian diet (which includes plant-derived foods, milk, and milk by-products. See diet in Sikhism) in accordance to their beliefs.

No description of Punjabi cuisine is complete without the myriad of famous desserts, such as kheer, gajar ka halwa, sooji (cream of wheat) halwa, rasmalai, gulab jamun and jalebi. Most desserts are ghee or dairy-based, use nuts such as almonds, walnuts, pistachios, cashews, and, raisins.

Many of the most popular elements of Anglo-Indian cuisine, such as tandoori foods, naan, pakoras and vegetable dishes with paneer, are derived from Punjabi styles.[167]

Punjabi food is well liked in the world for its flavors, spices, and, versatile use of produce, and so it is one of the most popular cuisines from the sub-continent. Last but not least are the chhole bhature and chhole kulche[168] which are famous all over the North India.

Rajasthan

Cooking in Rajasthan, an arid region, has been strongly shaped by the availability of ingredients. Food is generally cooked in milk or ghee, making it quite rich. Gram flour is a mainstay of Marwari food mainly due to the scarcity of vegetables in the area.[169]

Historically, food that could last for several days and be eaten without heating was preferred. Major dishes of a Rajasthani meal may include daal-baati, tarfini, raabdi, ghevar, bail-gatte, panchkoota, chaavadi, laapsi, kadhi and boondi. Typical snacks include bikaneri bhujia, mirchi bada, pyaaj kachori, and dal kachori.

Daal-baati is the most popular dish prepared in the state. It is usually supplemented with choorma, a mixture of finely ground baked rotis, sugar and ghee.[170]

Rajasthan is also influenced by the Rajput community who have liking for meat dishes. Their diet consisted of game meat and gave birth to dishes like laal maans, safed maas,[171] khad khargosh[172] and jungli maas.[173]

Sikkim

In Sikkim, various ethnic groups such as the Nepalese, Bhutias, and Lepchas have their own distinct cuisines. Nepalese cuisine is very popular in this area.

Rice is the staple food of the area, and meat and dairy products are also widely consumed. For centuries, traditional fermented foods and beverages have constituted about 20 percent of the local diet.

Depending on altitudinal variation, finger millet, wheat, buckwheat, barley, vegetables, potatoes, and soybeans are grown. Dhindo, daal bhat, gundruk, momo, gya thuk, ningro, phagshapa, and sel roti are some of the local dishes.

Alcoholic drinks are consumed by both men and women. Beef is eaten by Bhutias.[174]

Sindh

Sindhi cuisine refers to the native cuisine of the Sindhi people from the Sindh region, now in Pakistan. While Sindh is not geographically a part of modern India, its culinary traditions persist,[175] due to the sizeable number of Hindu Sindhis who migrated to India following the independence of Pakistan in 1947, especially in Sindhi enclaves such as Ulhasnagar and Gandhidam.

A typical meal in many Sindhi households includes wheat-based flatbread (phulka) and rice accompanied by two dishes, one with gravy and one dry. Lotus stem (known as kamal kakri) is also used in Sindhi dishes. Cooking vegetables by deep frying is common.

Some regular Sindhi dishes are sindhi kadhi,[176] sai bhaji, koki[177] and besan bhaji. Ingredients frequently used are mango powder, tamarind, kokum flowers, and dried pomegranate seeds.[178]

Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu is noted for its deep belief that serving food to others is a service to humanity, as is common in many regions of India. The region has a rich cuisine involving both traditional non-vegetarian and vegetarian dishes.

Tamil food is characterised by its use of rice, legumes, and lentils, along with distinct aromas and flavours achieved by the blending of spices such as mustard, curry leaves, tamarind, coriander, ginger, garlic, chili pepper, cinnamon, clove, cardamom, cumin, nutmeg, coconut and rose water.

The traditional way of eating involves being seated on the floor, having the food served on a plantain leaf, and using the right hand to eat. After the meal the plantain leaf is discarded but becomes food for free-ranging cattle and goats.

A meal (called saapadu) consists of rice with other typical Tamil dishes on a plantain leaf. A typical Tamilian would eat on a plantain leaf as it is believed to give a different flavour and taste to food. Also growing in popularity are stainless-steel trays, plates with a selection of different dishes in small bowls.

Tamil food is characterized by tiffin, which is a light food taken for breakfast or dinner, and meals which are usually taken during lunch. The word "curry" is derived from the Tamil kari, meaning something similar to "sauce".[179][180]

Southern regions such as Tirunelveli, Madurai, Paramakudi, Karaikudi, Chettinad and Kongu Nadu are noted for their spicy non-vegetarian dishes.[181][182] Dosa, idli, pongal and biryani are some of the popular dishes that are eaten with chutney and sambar. Fish and other seafoods are also very popular, because the state is located on the coast. Chicken and goat meat are the predominantly consumed meats in Tamil Nadu.

A typical Tamil vegetarian meal is heavily dependent on rice, vegetables and lentil preparations such as rasam and sambar, but there are variations. They have influenced Kerala as well in their kootu, arachi vitta sambhar[183] and molagootals (mulligatawny soup).

As mentioned above, the Chettinad variety of food uses many strong spices, such as pepper, garlic, fennel seeds and onions. Tamil food tends to be spicy compared to other parts of India so there is a tradition of finishing the meal with dahi (yogurt) is considered a soothing end to the meal.

Notably, Tamil Brahmin cuisine, the food of the Iyers and Iyengar community, is characterized by slightly different meal times and meal structures compared to other communities within the state.

Historically vegetarian, the cuisine is known for its milder flavor and avoidance of onion and garlic (although this practice appears to be disappearing with time).

After a light morning meal of filter coffee and different varieties of porridges (oatmeal and janata kanji are immensely popular), the main meal of the day, lunch/brunch is usually at 11 am and typically follows a two-three course meal structure. Steamed rice is the main dish, and is always accompanied by a seasonally steamed/sauteed vegetable (poriyal), and two or three types of tamarind stews, the most popular being sambhar and rasam. The meal typically ends with thair sadham (rice with yogurt), usually served with pickled mangoes or lemons.

Tiffin is the second meal of the day and features several breakfast favorites such as idli, rava idli, upma, dosa varieties, and vada, and is usually accompanied by chai.

Dinner is the simplest meal of the day, typically involving leftovers from either lunch or tiffin. Fresh seasonal fruit consumed in the state include bananas, papaya, honeydew and cantaloupe melons, jackfruit, mangos, apples, kasturi oranges, pomegranates, and nongu (hearts of palm).

Telangana

The cuisine of Telangana consists of the Telugu cuisine, of Telangana's Telugu people as well as Hyderabadi cuisine (also known as Nizami cuisine), of Telangana's Hyderabadi Muslim community.[184][185]

Hyderabadi food is based heavily on non-vegetarian ingredients, while Telugu food is a mix of both vegetarian and non-vegetarian ingredients. Telugu food is rich in spices and chillies are abundantly used. The food also generally tends to be more on the tangy side with tamarind and lime juice both used liberally as souring agents.

Rice is the staple food of Telugu people. Starch is consumed with a variety of curries and lentil soups or broths.[186][187] Vegetarian and non-vegetarian foods are both popular.

Hyderabadi cuisine includes popular delicacies such as biryani, haleem, Baghara baingan and kheema, while Hyderabadi day-to-day dishes see some similarities to Telanganite Telugu food, with its use of tamarind, rice, and lentils, along with meat.[186] Dahi (yogurt) is a common addition to meals, as a way of tempering spiciness.[188]

Tripura

The Tripuri people are the original inhabitants of the state of Tripura in northeast India. Today, they comprise the communities of Tipra, Reang, Jamatia, Noatia, and Uchoi, among others. The Tripuri are non-vegetarian,[189] although they have a minority of Vaishnavite vegetarians.[190]

The major ingredients of Tripuri cuisine include vegetables, herbs, pork, chicken, mutton, fishes, turtle, shrimps, crabs, freshwater mussels, periwinkles, edible freshwater snails and frogs.

Uttar Pradesh

Traditionally, Uttar Pradeshi cuisine consists of Awadhi, Bhojpuri, and Mughlai cuisine,[191] though a vast majority[citation needed] of the state is vegetarian, preferring dal, roti, sabzi, and rice. Pooris and kachoris are eaten on special occasions.

Chaat, samosa, and pakora, among the most popular snacks in India, originate from Uttar Pradesh.[192][193]

Well-known dishes include kebabs, dum biryani, and various mutton recipes. Sheer qorma, ghevar, gulab jamun, kheer, and ras malai are some of the popular desserts in this region.

Awadhi cuisine (Hindi: अवधी खाना) is from the city of Lucknow, which is the capital of the state of Uttar Pradesh in Central-South Asia and North India, and the cooking patterns of the city are similar to those of Central Asia, the Middle East, and other parts of North India. The cuisine consists of both vegetarian and non-vegetarian dishes.

Awadh has been greatly influenced by Mughal cooking techniques, and the cuisine of Lucknow bears similarities to those of Central Asia, Kashmir, Punjab and Hyderabad. The city is also known for its Nawabi foods.[194] The bawarchis and rakabdars of Awadh gave birth to the dum style of cooking or the art of cooking over a slow fire, which has become synonymous with Lucknow today.[195] Their spread consisted of elaborate dishes like kebabs, kormas, biryani, kaliya, nahari-kulchas, zarda, sheermal, roomali rotis, and warqi parathas.

The richness of Awadh cuisine lies not only in the variety of cuisine but also in the ingredients used like mutton, paneer, and rich spices, including cardamom and saffron.

Mughlai cuisine is a style of cooking developed in the Indian subcontinent by the imperial kitchens of the Mughal Empire. It represents the cooking styles used in North India (especially Uttar Pradesh).

The cuisine is strongly influenced by Central Asian cuisine, the region where the Chagatai-Turkic Mughal rulers originally hailed from, and has strongly influenced the regional cuisines of Kashmir and the Punjab region.[196][194]

The tastes of Mughlai cuisine vary from extremely mild to spicy, and is often associated with a distinctive aroma and the taste of ground and whole spices.

A Mughlai course is an elaborate buffet of main course dishes with a variety of accompaniments.[197]

Uttarakhand

Food from Uttrakhand is known to be healthy and wholesome to suit the high-energy necessities of the cold, mountainous region. It is a high-protein diet that makes heavy use of pulses and vegetables. Traditionally, it is cooked over wood or charcoal fire mostly using iron utensils.

While making use of condiments such as jeera, haldi and rai common in other Indian cuisines, Uttarakhand cuisine also use exotic ingredients such as jambu, timmer, ghandhraini and bhangira.

Although the people in Uttarakhand also make dishes common in other parts of northern India, several preparations are unique to Uttarakhand such as rus, chudkani,[198] dubuk, chadanji,[199] jholi, kapa, and more.

Among dressed salads and sauces, kheere ka raita,[200] nimbu mooli ka raita,[201] daarim ki khatai and aam ka fajitha[202] are also popular.

The cuisine mainly consists of food from two different sub-regions, Garhwal and Kumaon, though their basic ingredients are the same.[203] Both Kumaoni and Garhwali styles make liberal use of ghee, lentils or pulses, vegetables and bhaat (rice). They also use badi (sun-dried urad dal balls) and mungodi (sun-dried moong dal balls) as substitutes for vegetables at times.

During festivals and other celebrations, the people of Uttarakhand prepare special refreshments which include both salty preparations such as bada and sweet preparations such as pua and singal. Uttarakhand also has several sweets (mithai) such as singodi, bal-mithai, and malai laddu,[204] native to its traditions.

Gallery

- North India

-

Daulat Chaat in Old Delhi

-

Butter chicken and butter naan

-

Kashmiri Pulav

- West India

-

Locho and Idada

-

Chhole Upma

-

Tandoori lemonfish fry

- East India

-

Plantain dumplings

-

Luchi Alur Torkari

-

Bamboo steam rice

-

Tamul Paan

-

Prosad Thali

-

Tan Ngang

- South India

-

Khotto

-

Prawn Biryani

Hindu fasting cuisine

Hindu people fast on days such as Ekadashi, in honour of Lord Vishnu or his Avatars, Chaturthi in honour of Ganesh, Mondays in honour of Shiva, or Saturdays in honour of Hanuman or Saturn.[205]

Only certain kinds of foods are allowed to be eaten. These include milk and other dairy products (such as dahi), fruit, and Western food items such as sago,[206] potatoes,[207] purple-red sweet potatoes, amaranth seeds,[208] nuts and (shama millet).[209]

Popular fasting dishes include farari chevdo,[210] sabudana khichadi, and peanut soup.[211]

Diaspora and fusion cuisines

The interaction of various Indian diaspora communities with the native cultures in their new homes has resulted in the creation of many fusion cuisines, which blend aspects of Indian and other international cuisines. These cuisines tend to interpolate Indian seasoning and cooking techniques into their own national dishes.

Indian Chinese cuisine

Indian Chinese cuisine, also known as Indo-Chinese cuisine originated in the 19th century among the Chinese community of Calcutta, during the immigration of Hakka Chinese from Canton (present-day Guangzhou) seeking to escape the First and Second Opium Wars and political instability in the region.[212] Upon exposure to local Indian cuisine, they incorporated many spices and cooking techniques into their own cuisine, thus creating a unique fusion of Indian and Chinese cuisine.[212]

After 1947, many Cantonese immigrants opened restaurants in Calcutta, serving dishes that combined aspects of Indian cuisine with Cantonese cuisine.[213] In other parts of India, Indian Chinese cuisine is derived from Calcutta-Chinese cuisine, but bears little resemblance to their Chinese counterparts[213] as the dishes tend to be flavoured with cumin, coriander seeds, and turmeric, which with a few regional exceptions, are not traditionally associated with Chinese cuisine.[214] Chilli, ginger, garlic and dahi (yogurt) are also frequently used in dishes.[214]

Popular dishes include Chicken Manchurian, chicken lollipop, chilli chicken, Hakka noodles, Hunan chicken, chow mein, and Szechwan fried rice.

Soups such as Manchow soup and sweet corn soup are very popular, whereas desserts include ice cream on honey-fried noodles and date pancakes.

Chowmein is now known as one of the most favorite Chinese dishes in India. Especially in West Bengal, it is one of the most loved street foods.

Indian Thai cuisine

Thai cuisine was influenced by Indian cuisine, like as recorded by the Thai monk Buddhadasa Bhikku in his writing 'India's Benevolence to Thailand'. He wrote that Thai people learned how to use spices in their food in various ways from Indians. Thais also obtained the methods of making herbal medicines (Ayurveda) from the Indians. Some plants like sarabhi of family Guttiferae, kanika or harsinghar, phikun or Mimusops elengi and bunnak or the rose chestnut etc. were brought from India.

Malaysian Indian cuisine

Malaysian Indian cuisine, or the cooking of the ethnic Indian communities in Malaysia consists of adaptations of authentic dishes from India, as well as original creations inspired by the diverse food culture of Malaysia.

A typical Malaysian Indian dish is likely to be redolent with curry leaves, whole and powdered spice, and contains fresh coconut in various forms.

Ghee is still widely used for cooking, although vegetable oils and refined palm oils are now commonplace in home kitchens.

Indian Singaporean cuisine

Indian Singaporean cuisine refers to foods and beverages produced and consumed in Singapore that are derived, wholly or in part, from South Asian culinary traditions.

The great variety of Singaporean food includes Indian food, which tends to be Tamil cuisine, especially local Tamil Muslim cuisine, although North Indian food[215] has become more visible recently.

Indian dishes have become modified to different degrees, after years of contact with other Singaporean cultures, and in response to locally available ingredients, as well as changing local tastes.

Indian Indonesian cuisine

Indian-Indonesian cuisine refers to food and beverages in Indonesian cuisine that have influenced Indian cuisine—especially from Tamil, Punjabi, and Gujarati cuisine. These dishes are well integrated, such as appam, biryani, murtabak and curry.

Indian Filipino cuisine

Filipino cuisine, found throughout the Philippines archipelago, has been historically influenced by the Indian cuisine. Indian influences can also be noted in rice-based delicacies such as bibingka (analogous to the Indonesian bingka), puto, and puto bumbong, where the latter two are plausibly derived from the south Indian puttu, which also has variants throughout Maritime Southeast Asia (e.g. kue putu, putu mangkok).

The kare-kare, more popular in Luzon, on the other hand could trace its origins from the Seven Years' War when the British occupied Manila from 1762 to 1764 with a force that included Indian sepoys, who had to improvise Indian dishes given the lack of spices in the Philippines to make curry. This is said to explain the name and its supposed thick, yellow-to-orange annatto and peanut-based sauce, which alludes to a type of curry.

Atchara of Philippines originated from the Indian achar, which was transmitted to the Philippines via the acar of the Indonesia, Malaysia, and Brunei.

Anglo-Indian cuisine

Anglo-Indian cuisine developed during the period of British colonial rule in India, as British officials interacted with their Indian cooks.[216]

Well-known Anglo-Indian dishes include chutneys, salted beef tongue, kedgeree,[217] ball curry, fish rissoles, and mulligatawny soup.[216][218][219]

Desserts

Many Indian desserts, or mithai, are fried foods made with sugar, milk or condensed milk. Ingredients and preferred types of dessert vary by region. In the eastern part of India, for example, most are based on milk products.

Many are flavoured with almonds and pistachios, spiced with cardamon, nutmeg, cloves and black pepper, and decorated with nuts, or with gold or silver leaf. Popular Indian desserts include rasogolla, gulab jamun, jalebi, laddu, and peda.[220]

Beverages

Non-alcoholic beverages

Tea is a staple beverage throughout India, since the country is one of the largest producers of tea in the world. The most popular varieties of tea grown in India include Assam tea, Darjeeling tea and Nilgiri tea. It is prepared by boiling the tea leaves in a mix of water, milk, and spices such as cardamom, cloves, cinnamon, and ginger. In India, tea is often enjoyed with snacks like biscuits and pakoda.[citation needed]

Coffee is another popular beverage, but more popular in South India.[citation needed] Coffee is also cultivated in some parts of India. There are two varieties of coffee popular in India, which include Indian filter coffee and instant coffee.[citation needed]

Lassi is a traditional dahi (yogurt)-based drink in India.[221] It is made by blending yogurt with water or milk and spices. Salted lassi is more common in villages of Punjab and in Porbandar, Gujarat.[citation needed] Traditional lassi is sometimes flavoured with ground roasted cumin. Lassi can also be flavoured with ingredients such as sugar, rose water, mango, lemon, strawberry, and saffron.[222]

Sharbat is a sweet cold beverage prepared from fruits or flower petals.[223] It can be served in concentrate form and eaten with a spoon, or diluted with water to create a drink. Popular sharbats are made from plants such as rose, sandalwood, bel, gurhal (hibiscus), lemon, orange, pineapple, sarasaparilla and kokum, falsa (Grewia asiatica). In Ayurveda, sharbats are believed to hold medicinal value.[224]

Thandai is a cold drink prepared with a mixture of almonds, fennel seeds, watermelon kernels, rose petals, pepper, poppy seeds, cardamom, saffron, milk and sugar. It is native to India and is often associated with the Maha Shivaratri and Holi or Holla mahalla festival. Sometimes bhaang (cannabis) is added to prepare special thandai.

Other beverages include nimbu pani (lemonade), chaas, badam doodh (milk with nuts – mostly almonds – and cardamom), Aam panna, kokum sharbat, and coconut water.

Modern carbonated cold drinks unique to southern India include beverages, such as panner soda or goli soda, a mixture of carbonated water, rose water, rose milk, and sugar, naranga soda, a mixture of carbonated water, salt and lemon juice, and nannari sarbath, a mixture with sarasaparilla.

Sharbats with carbonated water are the most popular non-alcoholic beverages in Kerala and Tamil Nadu. Street shops in Central Kerala and Madurai region of Tamil Nadu are well known for these drinks which are also called kulukki sarbaths in Kerala.

-

Darjeeling tea in varieties.

-

Indian filter coffee is popular in Southern India.

-

Badam milk

-

Holi Special Chilled Thandai

Alcoholic beverages

Beer

Most beers in India are either lagers (4.8 percent alcohol) or strong lagers (8.9 percent). The Indian beer industry has witnessed steady growth of 10–17 percent per year over the last ten years.[when?] Production exceeded 170 million cases during the 2008–2009 financial year.[225] With the average age of the population decreasing and income levels on the rise, the popularity of beer in the country continues to increase.

Others

Other popular alcoholic drinks in India include fenny, a Goan liquor made from either coconut or the juice of the cashew apple. The state of Goa has registered for a geographical indicator to allow its fenny distilleries to claim exclusive rights to production of liquor under the name "fenny."[226]

Hadia is a rice beer, created by mixing herbs with boiled rice and leaving the mixture to ferment for around a week. It is served cold and is less alcoholic than other Indian liquors. Chuak is a similar drink from Tripura.

Palm wine, locally known as neera, is a sap extracted from inflorescences of various species of toddy palms.[227]

Chhaang is consumed by the people of Sikkim and the Darjeeling Himalayan hill region of West Bengal. It is drunk cold or at room temperature in summer, and often hot during cold weather. Chhaang is similar to traditional beer, brewed from barley, millet, or rice.[228]

Kallu (Chetthu Kallu) is a popular natural alcohol extracted from coconut and pine trees in Kerala. It is sold in local Kallu shops and is consumed with fried fish and chicken. Its alcoholic content is increased by addition of distilled alcohol.

Eating habits

Indians consider a healthy breakfast important. They generally prefer to drink tea or coffee with breakfast, though food preferences vary regionally. North Indian people prefer roti, parathas, and a vegetable dish accompanied by achar (a pickle) and some curd.[229] Various types of packaged pickles are available in the market. One of the oldest pickle-making companies in India is Harnarains,[230] which started in the 1860s in Old Delhi.

People of Gujarat prefer dhokla and milk, while south Indians prefer idli and dosa, generally accompanied by sambhar or sagu and various chutneys.[231]

Traditional lunch in India usually consists of a main dish of rice in the south and the east, and whole-wheat rotis in the north. It typically includes two or three kinds of vegetables, and sometimes items such as kulcha, naan, or parathas. Paan (stuffed, spiced and folded betel leaves) which aids digestion is often eaten after lunch and dinner in many parts of India.[36]

Indian families often gather for "evening snack time", similar to tea time to talk and have tea and snacks.

Dinner is considered the main meal of the day.[232] Also, many households, especially in north and central India, prefer having sweets after the dinner (similar to the Western concept of dessert after meals).

Dietary practices

In India people often follow dietary practices based on their religious belief:

- Most Hindu communities consider beef taboo since they believed that Hindu scriptures condemn cow slaughter. Cow slaughter has been banned in many states of India,[233] with the exceptions of the North-Eastern states, West Bengal and Kerala.

- Vaishnavism followers generally are strict lacto-vegetarians due to an emphasis on Ahimsa. They also do not consume garlic and onions.[citation needed]

- Jains follow a strict form of lacto-vegetarianism, known as Jain vegetarianism, which in addition to being completely lacto-vegetarian, also excludes all root vegetables such as carrots and potatoes because when the root is pulled up, organisms that live around the root also die.[234]

- Muslims do not eat pork or pork products.

- Except in certain North-Eastern regions, canines are not considered suitable for consumption.

Etiquette

Traditionally, meals in India are eaten while seated either on the floor, or on very low stools or mattress. Food is most often eaten with the hands rather than cutlery.

Often roti is used to scoop curry without allowing it to touch the hand. In the wheat-producing north, a piece of roti is gripped with the thumb and middle finger and ripped off while holding the roti down with the index finger.

A somewhat different method is used in the south for dosai, adai, and uththappam, where the middle finger is pressed down to hold the bread and the forefinger and thumb used to grip and separate a small part. Traditional serving styles vary regionally throughout India.

Contact with other cultures has affected Indian dining etiquette. For example, the Anglo-Indian middle class commonly uses spoons and forks, as is traditional in Western culture.[235]

In South India, cleaned banana leaves, which can be disposed of after meals, are used for serving food. When hot food is served on banana leaves, the leaves add distinctive aromas and taste to the food.[236] Leaf plates are less common today, except on special occasions.

Outside India

Indian migration has spread the culinary traditions of the subcontinent throughout the world. These cuisines have been adapted to local tastes, and have also affected local cuisines. The international appeal of curry has been compared to that of pizza.[237] Indian tandoor dishes such as chicken tikka also enjoy widespread popularity.[238]

Australia

A Roy Morgan Research survey taken between 2013 and 2018 found that Indian cuisine was the top-rated international food among 51% of Australians, behind Chinese, Italian, and Thai.[239]

Canada

As in the United Kingdom and the United States, Indian cuisine is widely available in Canada, especially in the cities of Toronto,[240] Vancouver,[241] and Ottawa where the majority of Canadians of South Asian heritage live.

China

Indian food is gaining popularity in China, where there are many Indian restaurants in Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen. Hong Kong alone has more than 50 Indian restaurants, some of which date back to the 1980s. Most of the Indian restaurants in Hong Kong are in Tsim Sha Tsui.[242]

Fiji

Indo-Fijians have a similar cuisine, often with Fijian influence.

Middle East

The Indian culinary scene in the Middle East has been influenced greatly by the large Indian diaspora in these countries. Centuries of trade relations and cultural exchange resulted in a significant influence on each region's cuisines. The use of the tandoor, which originated in northwestern India,[243] is an example.

The large influx of Indian expatriates into Middle Eastern countries during the 1970s and 1980s led to a boom in Indian restaurants to cater to this population and was also widely influenced by the local and international cuisines.

Nepal

Indian cuisine is available in the streets of Nepalese cities, including Kathmandu and Janakpur.

Southeast Asia

Other cuisines which borrow inspiration from Indian cooking styles include Cambodian, Lao, Filipino, Vietnamese, Indonesian, Thai, and Burmese cuisines. The spread of vegetarianism in other parts of Asia is often credited to Hindu and Buddhist practices.[244]

Indian cuisine is very popular in Southeast Asia, due to the strong Hindu and Buddhist cultural influence in the region. Indian cuisine has had considerable influence on Malaysian cooking styles[5] and also enjoys popularity in Singapore.[245][246] There are numerous North and South Indian restaurants in Singapore, mostly in Little India.

Singapore is also known for fusion cuisine combining traditional Singaporean cuisine with Indian influences. Fish head curry, for example, is a local creation. Indian influence on Malay cuisine dates to the 19th century.[247]

United Kingdom