History of Cologne

The History of Cologne covers over 2000 years of urban history. In the year 50, Cologne was elevated to a city under Roman law and named "Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium"; since the Frankish rule it is known as Cologne. The city became an influential merchant stronghold in the early Middle Ages due to its location on the Rhine, which allowed the most seasoned Cologne wholesalers to control the flow of goods from northern Italy to England. The archbishops promoted the perception of "Holy Cologne" when they developed the city to the capital of their Electorate of Cologne; to this end, they had both the semicircular city wall and the Gothic Cologne Cathedral built as a demonstration of power. In the 15th century, Cologne was able to shake off archiepiscopal rule and, as a Free Imperial City, enabled the burgher ruling class to achieve great splendor, visibly documented by the Cologne School of Painting. After the Thirty Years' War, however, the city's development stalled. Only after French occupation when in 1815, Cologne was incorporated into Prussia, the city experienced a steady upswing borne by industrialization. In 1880, the cathedral was completed as a national monument of German imperial unity providing the city with its well-known landmark. Extensive devastation in the Second World War was followed by decades of reconstruction, which only slowly restored Cologne to its emblematic urban panorama on the Rhine through the efforts of urban repair. Today with more than one million inhabitants, Cologne is the fourth largest city in Germany. It is primarily marketed as an event city, with Cologne Carnival being perceived as the biggest tourist attraction.

Demographic history of Cologne

[edit]In the time of Roman Late antiquity, the cultural development in northwestern Europe west of the Rhine was embodied by a network of urban settlements. Most important towns in the Rhineland were Trier, which served as imperial residence of the Western Roman Emperor from 293 to 395, and Cologne, where five Roman trunk roads intersected with the Rhine, also then used as a water transport route. When the Franks formed their kingdoms after the decline of Roman power, the Roman induced urban settlements in the Rhineland largely perished. Only a few places — such as Trier, Cologne and Mainz — remained continuously inhabited within the Roman urban scope, however with a significantly reduced population. Cologne, which had been inhabited by up to 20,000 people in Roman Late Antiquity,[1] counted in the year 700 about 3,000 settlers and was thus after Trier (5,000) the second largest town in the Rhineland. Further west, the urban tradition survived in more numerous places, none of them having gathered significantly more inhabitants. This applies, among others, to Tours, Rouen, Reims (5,000 each) and Paris (3.000). The largest cities in Western Europe were Rome (44,000) and Milan (21,000).[2]

In the following centuries, dynamic growth of Cologne was driven by enhanced merchant activities on river Rhine; in addition, the town became seat of an influential archbishop. In the year 1000, the city with 10,000 inhabitants was among the three largest cities in northwestern Europe, after Paris (15,000) and Rouen (12,000). From 1000 to 1200, Cologne experienced further steep growth and quadrupled its population to 40,000.[3] This expansion was mirrored by an intensified church building in romanesque style known as the "great century of Cologne church architecture"[4] from 1150 to 1250.

In the Middle Ages and the early modern period, Cologne was consistently among the 30 largest cities in Western Europe. This indicates the importance of the merchant center on the Rhine, because, in these periods, the number of inhabitants can be read as a good indicator of economic prosperity.[5] However, Cologne could hardly ever count itself among the leading metropolises in Western Europe. Around 1200, the archbishops expanded the city and made it the capital of their sphere of influence;[6] with a population of 40,000, Cologne reached a size comparable to London and Paris and was thus among the 10 largest cities in Western Europe.

In the following three centuries, the Rhine city, as a merchant center, unfolded a tightly linked trading network that included the Hanseatic towns of the Baltic Sea, in the west London and Bruges, but also trading places such as Bordeaux and Leipzig, and in the south the centers of Milan and Venice. Within this network, Cologne developed a strong but not dominant position. While other cities continued to grow, Cologne never exceeded a population of about 45,000 until the end of the 18th century. As early as 1300, the Flanders city of Ghent became a mercantile center of cloth industry with 64,000 inhabitants, and thus the largest city in the northwest; in those years Paris already reached a population of 75,000 and Milan, as a commercial metropolis, had about 100,000 inhabitants.[7]

When Cologne was elevated to Free Imperial City status at the end of the 15th century, it was the largest city in the Holy Roman Empire, but only one of several important trading centers between the Scheldt and Elbe. Among them were in Flanders the cities of Ghent (45,000), Bruges and Tournai (35,000 each), as well as Brussels (33,000) and Antwerp (30,000), and in the southern part of Germany the cities of Nuremberg (38,000) and Augsburg (30,000); of the Hanseatic cities, the most important were Hamburg, Gdansk (Danzig) (30,000 each) and Lübeck (25.000). The dominant commercial places of Western Europe were Milan and Venice (100,000 each); among the political centers, the most numerous population had Naples (125,000), Paris (94,000), and London (50,000).[8]

In the second half of the 16th century, trade flows increasingly shifted away from the Rhine to sea routes, diminishing Cologne's influence on the long-distance trade network. Cologne did continue to maintain its population of around 40,000 until the 18th century. This is remarkably enough given the belligerent and epidemic vicissitudes that hit other commercial centers. Nevertheless, the city of Cologne became relatively less important and its commercial sphere of influence was mainly reduced to the regional environment. Antwerp established itself around 1560 with 100,000 inhabitants as the commercial metropolis of the northwest.[9]

The military conflicts of the Thirty Years' War were by and large beneficial for Cologne because it was considered impregnable and could benefit from the arms trade; in any case, the Rhine city did not suffer a blow like the cities of Nuremberg, Augsburg or Magdeburg all three until then on a steep growth path. Cologne had little share in the Atlantic trade that began in the 17th century, which made Amsterdam (180,000) to the Netherlands trading metropolis and Hamburg (70,000) the largest German trading city. Thus in 1700, Cologne dropped out of the top 30 list of largest cities in Western Europe. Increasingly, population growth was absorbed by the political centers such as London (575,000), Paris (500,000), and Vienna (114,000), all on the way to a form of modern European metropolises. Berlin (50,000) still had its dynamic growth ahead of it, and achieved the status of a major urban center (“Grossstadt”) only in 1763, when its population exceeded permanently 100,000 inhabitants.[10]

With the onset of industrialization, Cologne doubled its population between 1810 (45,000) and 1846 (90,000) and was in 1850 the sixth largest city in Central Europe after Berlin, Vienna, Hamburg, Prague and Breslau. In the same period however, London was already inhabited by more than 2 million people, and Paris population surpassed 1 million. Industrialization as the driver of city size was exemplified by the British industrial cities Liverpool, Glasgow and Manchester, all exceeding 300,000 inhabitants by 1850.[11]

During the entrepreneurial boom of the Gründerzeit, Cologne benefited from the railroad network that crossed the Rhine in the heart of the city. Cologne managed to increase its population — also through generous expansion of the urban area — to 650,000 by World War I. After the war, Cologne was one of the four largest cities in the German Empire, after Berlin (1.9 million) and Hamburg (985,000) and about equal with Munich (630,000). In 1939, more than 770,000 people lived in Cologne. The city was able to recover after the extensive destruction in World War II and grew by more than 30% between 1939 and 1975 sustained by a very diversified economic structure. In 2000, Cologne, as megacity with more than one million inhabitants, was Germany's fourth-largest city after Berlin, Hamburg, and Munich; in northwestern Europe, Cologne ranked sixth after London, Paris, Hamburg, Brussels and Copenhagen. When considering Western Europe (EU in 2000 borders), the Rhine city was among the 20 largest metropolises.[12]

Early history

[edit]Roman period

[edit]

In 39 BC the Germanic tribe of the Ubii entered into an agreement with the forces of the Roman General Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa and settled on the left bank of the Rhine. Their headquarters was Oppidum Ubiorum (settlement of the Ubii) and at the same time an important Roman military base. In 50 AD the Cologne-born Agrippina the Younger, wife of the Emperor Claudius, asked for her home village to be raised to the status of a colonia — a city under Roman law. It was then renamed Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensis (colony of Claudius and the altar of Agrippina), shortened to Colonia Agrippina (Colony of Agrippina). In 80 AD the Eifel Aqueduct was built. It was one of the longest aqueducts of the Roman Empire, delivering 20,000 cubic metres of water to the city every day. Ten years later, the colonia became the capital of the Roman province of Lower Germany, Germania Inferior, with a total population of 45,000 people[citation needed][dubious – discuss] occupying 96.8 hectares.[13]

In 260 AD Postumus made Cologne the capital of the Gallic Empire, which included the Gallic provinces, the German provinces to the left of the Rhine, Britannia, and the provinces of Hispania. The Gallic Empire lasted only fourteen years.

By the 3rd century, only some 20,000 people lived in and around the town.[citation needed] In 310 AD, Emperor Constantine I had a bridge constructed over the Rhine, guarded by the castellum Divitia. Divitia later became a part of Cologne with the name Deutz.

The presence of Jews in Cologne was documented in AD 321. When exactly the first Jews arrived in the Rhineland area cannot now be established, but the Cologne community claims to be the oldest north of the Alps.[14] As early as 321 AD, an edict by the Emperor Constantine allowed Jews to be elected to the City Council.

Frankish rule

[edit]

Colonia was pillaged several times by the Franks in the 4th century. Two lavish burial sites located near the Cathedral date from this period. In 355 AD the Alemanni tribes besieged the town for 10 months, finally taking and plundering it. At the time, the garrison of Colonia Agrippina was under the generalship of Marcus Vitellus. The Romans re-occupied the city several months afterwards by Julian. The city finally fell to the Ripuarian Franks in 462 AD.

Cologne served as a base for the Carolingian conversion of the Saxons and Frisians. In 795 the chaplain to Charlemagne, Hildebold, was elevated to the newly created archbishopric of Cologne. After the death of Charlemagne, Cologne became part of Middle Francia. Archbishop Gunther was excommunicated in 863 for his support of the divorce and remarriage of Lothair II. In 873 Gunther's successor Wilbert consecrated what would become known as the Alter Dom (old cathedral), the predecessor of Cologne Cathedral. With the death of Lothair in 876, Cologne fell to East Francia under Louis the German. The city was burnt down by Vikings in the winter of 881/2.

In the early 10th century, the dukes of Lorraine seceded from East Francia. Cologne passed to East Francia but was soon reconquered by Henry the Fowler, deciding its fate as a city of the Holy Roman Empire (and eventually Germany) rather than France.

Cologne in the Holy Roman Empire

[edit]Later Middle Ages

[edit]Cologne's first Christian bishop was Maternus. He was responsible for the construction of the first cathedral, a square building erected early in the 4th century. In 794, Hildebald (or Hildebold) was the first Bishop of Cologne to be appointed archbishop. Bruno I (925–965), younger brother of Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor, founded several monasteries here.

The dynasty of the Ezzonids, later Counts of Berg, counted 7 archbishops during that period and consolidated the powers of the archbishopric over imperial affairs. The archbishops of Cologne became very influential as advisers to the Saxon, Salian and Hohenstaufen dynasties. From 1031 they also held the office of Arch-Chancellor of Italy. Their authority culminated[clarification needed] under Archbishop Engelbert II of Berg, imperial administrator (Reichsprovisor) and tutor to the emperor's son. Between 1216 and 1225, Engelbert fought for the establishment and security of the archdiocese of Cologne both as an ecclesiastical authority and as a secular territory. This led to his murder in 1225.

Construction of the Gothic cathedral started in 1248 under Konrad von Hochstaden. The eastern arm was completed and consecrated in 1322. Construction of the western arm was halted in 1475, and it would remain unfinished until 1880.

In 1074 the commune was formed. By the 13th century, the relationship between the city and its archbishop had become difficult, and after the Battle of Worringen in 1288, the forces of Brabant and the citizenry of Cologne captured Archbishop Siegfried of Westerburg (1274–97),[15] resulting in almost complete freedom for the city. To regain his liberty the archbishop recognized the political independence of Cologne but reserved certain rights, notably the administration of justice.

Long-distance trade in the Baltic intensified as the major trading towns came together in the Hanseatic League under the leadership of Lübeck. The League was a business alliance of trading cities and their guilds that dominated trade along the coast of Northern Europe. It flourished from the 1200 to 1500 and continued with lesser importance thereafter. The chief cities were Cologne on the Rhine, Hamburg and Bremen on the North Sea, and Lübeck on the Baltic.[16] Cologne was a leading member, especially because of its trade with England. The Hanseatic League gave merchants special privileges in member cities, which dominated trade in the Baltic Sea and the North Sea. Cologne's hinterland in Germany gave it an added advantage over the other Hanseatic cities, and it became the largest city in Germany and the region. Cologne's central location on the Rhine placed it at the intersection of the major trade routes between east and west and was the basis of Cologne's growth.[17] The economic structures of medieval and early modern Cologne were based on the city's major harbor, its location as a transport hub, and its entrepreneurial merchants who built ties with merchants in other Hanseatic cities.[18]

Cologne effectively became a free city after 1288, and in 1475 it was formally made a free imperial city, a status that it held until annexed by France on May 28, 1796. The Archbishopric of Cologne was a state in its own right within the Holy Roman Empire, but the city was independent, and the archbishops were usually not allowed to enter it. Instead, they took up residence in Bonn and later in Brühl until they returned in 1821.

Cologne Cathedral housed sacred relics that made it a destination for many worshippers. With the bishop not resident, the city was ruled by patricians (merchants carrying on long-distance trade). The craftsmen formed guilds, which sought to obtain control of the towns. The guilds were governed by strict rules. A few were open to women. Society was divided into sharply demarcated classes: the clergy, physicians, merchants, and various guilds of artisans; full citizenship was not available to paupers. Political tensions arose from issues of taxation, public spending, regulation of business, and market supervision, as well as the limits of corporate autonomy.[19]

The first pogrom against the Jews of Cologne occurred in 1349, when they were used as scapegoats for the Black Death.[20] In 1424 they were evicted from the city. They were allowed back again in 1798.

Cologne as Free Imperial City

[edit]Cologne Diocesan Feud

[edit]

A dispute between Archbishop Ruprecht of the Palatinate and the chapter of Cologne cathedral eventually evolved into a war with international involvement in 1474, known as the Cologne Diocesan Feud. This plunged the city of Cologne into an existential crisis. Since the archbishop refrained to abide by the financial agreements he had entered into when elected in 1463, the cathedral chapter appointed Landgrave Hermann IV of Hesse as diocesan administrator in 1473. Perceived as insubordination, the archbishop in consequence asked for military assistance from the powerful Duke of Burgundy, Charles the Bold, ruler of Flanders and Dutch regions. When Charles started the campaign with a well equipped army and headed for a siege of Neuss, part of Cologne electorate, and threatened to subsequently attack Cologne, the burghers feared for their independence. The city began extensive preparations for war, reinforced the city walls and sent a contingent of troops to defend Neuss. Within months, the citizenry succeeded in persuading Emperor Friedrich III to intervene with an imperial army; their arrival before Neuss forced the Burgundian troops to withdraw from the siege. Subsequently, the emperor officially elevated Cologne to the status of a Free imperial city. However, since the city itself had to bear the extraordinarily high war costs, including the maintenance of the imperial army, the city's finances were completely shattered. Cologne needed decades to regain its financial leeway.[21]

Steelyard for English trade

[edit]

Traditionally, the most important stronghold for Cologne's long-distance commerce was the Steelyard (Stalhof) in London. This prestigious trading post, endowed with trading privileges, allowed Cologne merchants to dominate English trade along the Rhine. The status of the steelyard was the cause of the Anglo-Hanseatic War in 1469, which was not settled until 1474. This dispute was primarily fought as a privateer war. Cologne however remained neutral adhering to its special relations with the English capital for more than 300 years, and even accepted being excluded from the Hanseatic League in 1471. Only after the League had prevailed in the caper war, the steelyard being restituted to the merchants, and the old privileges being renewed by the English crown, Cologne was re-incorporated into Hanseatic League in 1476.[22] The English trade remained a major asset in Cologne's long-distance commerce until the second half of the 16th century, and England continued to flourish as primary market for wine traded from Cologne. The city’s merchants succeeded in largely monopolizing the distribution of English tin. In addition, the Cologne merchants dominated the English trade in armaments (swords, armor, spears).[23] Overall, Cologne prospered as merchant city until the middle of the 16th century, which continued to control the flow of goods across the Rhine from London to Italy and at the same time linked them with west-east trade routes to Frankfurt and Leipzig. In fact, Cologne merchants could be found in all European commercial centers.[24] The central importance of Cologne's commerce throughout the Reich was also reflected in the fact that the Cologne Mark was officially designated the Reichsmünzgewicht (imperial currency standard) by Emperor Charles V in 1524. The Cologne penny, 160 of which were struck from one Cologne mark, was a standard currency of the High Middle Ages.[25]

Presence of emperor and king

[edit]

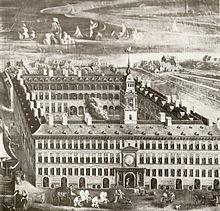

Between 1484 and 1531, emperors and kings often spent time in Cologne, enabling Cologne patricians a welcome proximity to Habsburg dynasty. As an indirect result of the Cologne Diocesan Feud, in 1477 heir Maximilian of Austria had married Maria, Duchess of Burgundy, thus enabling Habsburg access to the rich Burgundian lands of Flanders and the Netherlands. To secure this inheritance as a permanent possession, the royal presence in the region proved to be beneficial. In 1484 Maximilian was crowned German king to become the German deputy of his imperial father Frederick III. The extended festivities took place in Cologne, giving the City that year the appearance of Habsburg capital. Maximilian appointed the Cologne merchant Nicasius Hackeney as his chief financial advisor. In 1505, the Imperial Diet (Reichstag) was held in Cologne with all grandeur; it was perceived from contemporaries as the high point of Maximilian's imperial rule. Another diet, although started in Trier, was continued and concluded in 1512 in Cologne. Charles V was crowned Roman-German king in 1520, Ferdinand I in 1531. In both cases coronation ceremonies adhered to the customary practice known for centuries. Cologne archbishop acted as coronator in the ceremony in Palatine Chapel in Aachen, thereafter the coronation procession moved to Cologne to pay homage to the Three Magi in Cologne Cathedral. The final coronation festivities took place with great splendor in the city of Cologne. For the celebration in 1531, the Cologne Council had Anton Woensam produce a detailed Cologne city view, used as present for the newly crowned Ferdinand to highlight Cologne's status and greatness.[26] Emperor Charles V. also raised a Cologne patrician to his personal adviser. The twelve-time Cologne mayor Arnt von Siegen became a consultee in topics of faith policy. Unsurprisingly, the Emperor resided in the Siegen city palace at Holzmarkt during his visits to Cologne in 1545 and 1550.[27]

Oligarchic cronies in the council

[edit]

After the Cologne Diocesan Feud in 1475, Cologne was elevated as a Free Imperial City, but left with significant financial burdens that brought the city to the brink of insolvency. The debtors were predominantly the wealthy merchants of Cologne, who had been forced to subscribe to compulsory bonds for financing purposes. The council, dominated by these circles, tried to maintain the city's solvency by raising indirect taxes - especially on food and wine - in order to assure the debt service.[28]

In fact, during the heyday of the imperial city, Cologne Council was dominated by a small group of influential and very wealthy families who regarded themselves as Cologne patriciate; through a circle of council friends, they ensured that only initiated people moved up. This created an oligarchic rule in which corruption and favoritism increasingly spread, which became proverbial as „Kölscher Klüngel“ (Cologne cronyism). A center was formed by a lobby of councilmen who called themselves krensgin (chaplet) and who apparently made most of the important decisions, even without consulting the other members of the 49-member city council.[29] The non-transparent financial practices and the high taxation sometimes perceived as arbitrary led to an ongoing dispute within the city's leadership circles, which, after an attempted overthrow averted in 1482, was only resolved in 1513 by an amendment of the city constitution known as „Transfixbrief“ (Transfix letter).[30]

In 1481, councilor Werner von Lyskirchen, who was descended from one of Cologne's old patrician families, used the latent discontent in cooperative circles („Gaffeln“) and guilds to attempt a coup. The action, which went down in the chronicles as the "Große Schickung" (big dispatch) was quickly stifled by rival families and partisans, and Werner was eventually beheaded. The oligarchic structures that dominated the city remained.[31] In the course of a dispute in 1512, the small circles in the council were tempted to bend the law and commit fraud in order to defend their privileges, at least from the point of view of rival citizens. A riot broke out in January 1513; the burghers organized in cooperative circles (Gaffeln) seized power and deprived the council of its authority. Ten former councilmen were convicted of misconduct and executed; the representatives of the Gaffeln reformed taxation and held a new election.[32] New rules of conduct, intended to contain the re-emergence of oligarchic structures, were codified by December 1513 in an amendment letter (Transfixbrief), which supplemented the city constitution (Verbundbrief) in force since 1396. Among other things, the new regulations extended the rights of burghers, especially the inviolability of person and home.[33]

Cathedral construction interrupted and suspended

[edit]

When the city of Cologne mobilized all its forces in 1474 to arm itself against the advancing Duke of Burgundy, the construction work at Cologne Cathedral needed to be interrupted as well. The craftsmen were obliged to reinforce the city fortifications. Johann Kuyn von Frankenberg, the last master mason of the cathedral in the Middle Ages known by name, had to dissolve the masonry (Dombauhütte). After the war, Archbishop Hermann of Hesse refrained from continuing construction for about 30 years due to the excessive over-indebtedness of the Electorate of Cologne. He apparently used the donations, which continued to flow in abundance, to regain the financial leeway of the prince-archbishopric. It was not until his successor, Archbishop Philip II of Daun-Oberstein, that the cathedral masonry was re-established and the late gothic stained glass windows were installed in the north aisle of the Cathedral in 1508. They are considered to be of particularly high quality, for which the most respected representatives of the Cologne School of Painting created the designs. Eventually, the regular flow of construction activities stalled after 1525, because the most important financing instrument, the trade with indulgences, dried up due to the Reformation. At the latest in 1560, the cathedral construction was entirely suspended — and was only resumed in 1823.[34]

Silk made in Cologne

[edit]Silk production, which had been costumary practice in Cologne since the early Middle Ages, experienced its last flowering by the middle of the 16th century.[35] Along with Paris, Cologne was considered one of the great production centers north of the Alps.[36] Around 1500, silk cloth probably made up for Cologne's most successful export commerce.[37] The production of silk fabrics was controlled by the Silk Office (Seidenamt), a guild in which predominantly women were active. This practice, which was maintained only in Cologne except in Paris, allowed a larger number of female guild masters to achieve considerable wealth. For the daughters of upper class families, entering the silk business became a recognized career prospect. The most famous female guild master was Fygen Lutzenkirchen, who is considered to be the most successful silk entrepreneur in Cologne and was one of the wealthiest citizens of Cologne around 1498.[38] Silk production was closely linked to the silk trade because the raw silk had to be imported from northern Italian trading centers, usually via Venice and Milan. The silk weaving and craft processing - braid weaving, silk embroidery[39] - was organized mainly through the putting-out system. The wholesaler prefinanced the raw materials and left the craftswomen to work at home. The main buyers of Cologne's silk products were the clergy of Cologne and the export markets in Frankfurt, Strasbourg and Leipzig. On the markets in Flanders (Bruges, Antwerp, Ghent), Cologne merchants increasingly came up against intense local competition, which by the middle of the 16th century became increasingly noticeable in Cologne as well.[40] At the end of its heyday in 1560, Cologne counted 60 to 70 silk merchants who processed 700 bales of silk each year.[41]

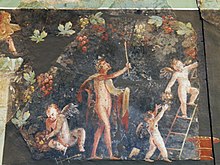

Patricians' seek after prestigious splendor

[edit]From the last decades of the 15th century on, the patricians of Cologne felt an increased need to express their status and therefore developed a lively activity as benefactors. Many of them ordered large winged altarpieces, the wealthiest financed entire chapels or parts of church furnishings. Therefore, by the end of the 18th century, in "Cologne were more medieval works of art than anywhere else in the world."[42]

Some families had large courtyards built in the city. Nicasius Hackeney, who was particularly close to the emperor Maximilian as his chief financial administrator, had the Hackeney'schen Hof built around 1505 at Neumarkt, which also served the emperor as a city palace.[43] Johann Rinck from a dynasty of influential merchants and mayors built at the same time the Rinkenhof opposite St. Mauritius.[44] Both palaces demonstrated with a polygonal stair tower the importance of their owners; a generation later, the twelve-time mayor Arnt von Siegen equipped his family mansion on Holzmarkt with a comparable tower. Thus, these towers became a status demonstrating meaning, cited in public buildings until the 19th century (for example, at the Zeughaus and at the Stapelhaus).[45] The foundation of chapels should not only serve the representative memory, but above all the salvation of the donors. In 1493, mayor Johann von Hirtz donated a chapel in St. Maria im Kapitol, today known as Hirtz Chapel; Johannes Hardenrath and his wife Agnes van Merle decided to commission the New Sacristy at the Kartäuserkirche (Carthusian Church) St. Barbara in 1510. Their intention materialized into the most refined sling vault of late Gothic church architecture in Cologne.[46]

-

Imperial Palace at Neumarkt (Hackeney)

-

Estate with tower at Holzmarkt (Siegen)

From the pronounced need for prestige benefited the numerous late Gothic masters of the Cologne School of Painting, whose best known were commissioned with large-scale altarpieces.[47] Among the most notable painters were the Master of the Holy Kinship, sometimes identified with Lambert von Luytge,[48] and the Master of the Saint Bartholomew Altarpiece, who has been introduced as a "genius without a name" in recent art history.[49] Both show the late Gothic painting in highest perfection expressed in the somewhat conservative Cologne style. The most sophisticated mastery of Cologne late Gothic sculpture is realized in the rood screen of St. Pantaleon Church, attributed to Master Tilman, and donated by Abbot Johannes Lüninck around 1502.[50]

-

Master of the Holy Kinship (c. 1493)

-

Master of Bartholomew Altarpiece (c. 1501)

Printed in Cologne

[edit]

The emerging technology of letterpress printing quickly was adopted in Cologne; as early as 1464, Ulrich Zell printed the first book. Until the end of the 15th century, there was evidence of 20 printing works in Cologne, producing more than 1200 different editions. This made Cologne - after Venice, Paris and Rome - a leading book printing center in Europe.[51] For the families involved in the printing and publishing business, such as the Quentel, Birckmann and Gymnich, it was a prospering venture. Many of them expanded to other metropolises in Europe and formed cross-city cooperatives. Peter Quentel, the busiest in the new industry, was re-elected as a Cologne councilman for many years.[52] In 1524, Quentel published an edition in Low German language of Luther’s New Testament translation; from the late 1520s, however, the printing and distribution of Lutheran books was banned by the Cologne Council. Again, it was Peter Quentel who published the first complete German translation of the Bible by Johann Dietenberger (the so-called Dietenberger Bible), which was printed in Mainz in 1534 and eventually gained recognition as one of the Catholic correction Bibles.[53]

By developing into a leading publishing place for Latin-language works Cologne gained an exceptional position compared to all other book printing centers of the empire. The Cologne publishers aimed at nationwide distribution and unleashed a program including primarily religious, scientific, and humanistic works. For example, along with Basel, Cologne was the leading printing center to publish the writings of the humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam. Moreover, Cologne remained the only one of the major imperial cities to remain Catholic, and thus offered a comprehensive book program of counter-Reformation works that continued to argue in Latin.[54] The book that, from today's perspective, most prominently represents the Cologne printing industry, however, is the Koelhoff Chronicle with the title "Die Cronica van der hilliger Stat van Coellen" (Chronicle of the Holy City of Cologne): the work written in the Ripuarian dialect of Cologne region was published in 1499 by Johann Koelhoff the Younger. Today, it is considered the high point of late medieval Cologne city history.[55]

Mockery of obscurors from Cologne

[edit]

At the beginning of the 16th century, a pamphleteering battle developed from Cologne throughout the empire over whether Jewish books — and in particular the Talmud — should be confiscated and burnt, with the intention of stifling the Jewish faith. The driver of this anti-Jewish action was Johannes Pfefferkorn, a Jew convert to Catholic Christianity who was apparently supported by the Cologne Dominican Order;[56] the Dominican theologian Jacob van Hoogstraaten, prior to the convent of Cologne, and acting as a papal inquisitor, flanked the anti-Jewish religious propaganda with expert opinions and prohibitory pamphlets, which were mainly directed against Johannes Reuchlin, a leading humanist and Hebraist. This anti-Jewish attitude also found expression in Cologne Cathedral. A series of stone reliefs, donated by the former Jew Victor von Carben, exemplifies the change from Judaism to Christianity.[57] The controversy, which spread across the whole Empire and engaged numerous Humanists and Emperor Maximilian, exposed van Hoogstraaten and the Cologne University faculty to the ridicule of the Letters of Obscure Men written by humanists, which discredited Cologne's theological conservatism for decades to come. The book controversy was eventually eclipsed by the onset of the Reformation.[58]

Simple-minded apprehension averted

[edit]

The pioneering theses of Martin Luther triggered ongoing controversy also in Cologne over whether and to what degree the church should renew itself. On the occasion of the coronation of Emperor Charles V in 1520, the writings of the Augustinian monk were publicly burned in the cathedral courtyard and Luther’s theses persecuted as heresy. The city council decided in 1527 to banish all Lutherans of the city, but claimed to pursue a policy of reconciliation, which the city defended to the Diet of 1532 - as did the imperial cities of Nuremberg, Augsburg or Frankfurt.[59] Persons who publicly professed Reformation ideas, such as the preacher Adolf Clarenbach and Peter Fliesteden were handed over by the council to the archbishop's jurisdiction. Archbishop Hermann of Wied, who wanted to prove his authority in religious matters, sentenced them to death at the stake. In the following years however, the God-fearing archbishop, who perceived church debauchery as an abomination, tried to set the Archbishopric on a course of renewal; the efforts eventually proved to be in vain. In the attempt to bridge the opposing positions of the faith dispute, Hermann progressively endorsed Reformation ideas, and finally invited the reform theologians Martin Bucer and Philipp Melanchthon to the Rhine, who published the programmatic paper "Einfältiges Bedenken" (Simple-minded Apprehension) on behalf of the archbishop. The counter-position, deep-routed in the Catholic conviction of the cathedral chapter, was formulated by Johannes Gropper, one of the leading Catholic theologians of his time.[60] In 1544, the bishop had a preacher's pulpit erected in Cologne Cathedral, with the intention to emphasize the importance of the preacher's word in accordance to reformist doctrine.[61] Thus, the Catholic party in the archdiocese and in the Cologne city council finally became suspicious of Hermann; longtime councillor Arnt von Siegen, a devout Catholic, leveraged his access to Charles V. In 1547, the emperor forced the archbishop to resign. In this way, the last, possibly too simple-minded attempt, to outbalance the schism in the empire, proved to be a complete failure.[62] The successors, the archbishops Adolf and Anton of Schaumburg, steered the archbishopric back on a clear Catholic course.[63]

Trade routes to Flanders

[edit]

For the Cologne commerce, the trade route to Flanders and the North Sea was of foundational importance. In the 16th century, it needed to be realigned as trading flows shifted from Bruges to Antwerp, which emerged as the economic center of Europe in the mid-16th century.[64] By 1526, the city on the Scheldt surpassed 50,000 inhabitants and outnumbered Cologne,[65] and by 1560 Antwerp had doubled its population.[66] In contrast, the importance of the Hanseatic Kontor of Bruges faded until the end of the 15th century, since Bruges could no longer be approached by seagoing ships due to the silting of the Zwin. Antwerp benefited from overseas trade flows; Portuguese merchants made the city a hub for long-distance import, for example to distribute sugar and pepper. Eventually, the Hanseatic League moved its Kontor to Antwerp in 1545 and had a prestigious new trading house built by Cornelis Floris II from 1563 to 1569; however, it was only used to one-fifth of its capacity. Cologne merchants found it increasingly difficult to hold their own against international competition. To avoid confessional unrest in Antwerp, Portuguese, Italian as well as Flemish merchants settled directly in Cologne. They imported grain and furs, but above all cloth and silk fabrics, which put them in direct competition with Cologne's production. At times, the non-Cologne merchants bundled a third of Cologne's long-distance trade.[67]

Renaissance in Cologne

[edit]In the 16th century, the patricians of Cologne began to reflect the Renaissance art trends they got to know on their trade journeys especially in Flanders, when commissioning works of art.[68] In 1517, the Cologne families Hackeney, Hardenrath, von Merle, von Straelen, Salm and von Berchem donated a rood screen for St. Maria im Kapitol; the elaborate work was ordered from an art carver in Mechelen, who thus made the Flemish Renaissance known in Cologne.[69] The town hall’s extension, called Löwenhof (Lion‘s Courtyard), was built in 1540 by Laurenz Cronenberg blending elements in late Gothic and Renaissance style. The Antwerp-born Cornelis Floris was commissioned by the cathedral chapter in 1561 to erect the epitaphs of the two archbishops from the house of Schaumburg, whose depiction gained proverbial recognition in Cologne as the Floris style.[70] Floris was also requested for the design of the city hall loggia, which was built from 1567; the construction, however, was assigned to the Cologne stonemason Wilhelm Vernukken.[71] The most sought-after Cologne Renaissance painter was Barthel Bruyn the Elder, who developed his own form for portrait paintings in Cologne.[72] Families who could afford it, however, had their members portrayed in London by the royal court painter Hans Holbein the Younger.[73]

-

Flemish: rood screen in St. Maria im Kapitol

-

Transitional style: Löwenhof in the City Hall

-

Floris style: epitaph in Cologne Cathedral

-

Triumphant arch style: City Hall Loggia

Efforts for the Cologne trade

[edit]

In the 1550s, it became apparent that international trade was undergoing a fundamental change. Kontors based trade underpinned with trading privileges was losing cohesive strength; as overseas destinations were increasingly discovered, long-distance trade shifted away from the Rhine to the North Sea. Antwerp, which by 1560 had more than 100,000 inhabitants, emerged as the economic center of Europe and developed great commercial dynamism, displacing the Cologne merchants.[74] In southern Germany, the imperial cities of Augsburg and Nürnberg had also developed into important trading hubs; both cities had grown to over 30,000 inhabitants, almost the size of Cologne. This was also true for Magdeburg, which benefited from the staple rights on the Elbe.[75] The Cologne wholesalers, who dominated the city's council, therefore sought to strengthen Cologne's position in international trade. In 1553, the Cologne commodity exchange was founded inspired by Antwerp practice, which allowed the trading of commodity contracts. Additionally, the bill of exchange business became established when the Antwerp finance business partially shifted to Cologne.[76] In order to strengthen its traditional business branches - especially wine and cloth - Cologne became intensively involved in the Hanseatic League and in 1556 created the role of a syndic, a kind of secretary-general in an institution that until then had not known any representative.[77] The position was assigned to Heinrich Sudermann of Cologne, who was to use diplomatic means to prolong the old trading privileges. However, after Elizabeth I had taken up the government in England in 1558, it was not possible to make her endorse the continuation of the privileges for the Stalhof in London, whose importance therefore diminished over the years. After the relocation of the flanders Kontor to Antwerp and the construction of a respresentative trading post from 1563 to 1569, Sudermann struggled - ultimately in vain - to give the Kontor greater economic relevance.[78] More successful was the initiative of the Cologne Council to strengthen the trading business on the Rhine by building a new stacking house (Stapelhaus) (1558-1561). The building allowed, above all, to handle the fish trade more effectively; despite all international adversities, Cologne still benefited considerably from the Stapelrecht, that continued to remain in force.[79]

King's coronation in Frankfurt

[edit]Maximilian II got crowned German king in November 1562 in Frankfurt am Main - and not in Aachen, as generations of his ancestors. The ritualized procession that the coronator and king had celebrated since time immemorial from Aachen to Cologne to visit the shrine of the Three Kings was dispensed with. The king skipped the tradition, to pay homage to the Magi in Cologne. The coronation festivities, which for centuries had guaranteed Cologne a closeness to the imperial dominion and had given it a great character since 1484, were held in Frankfurt am Main. This Cologne setback resulted because Archbishop Frederick IV of Wied had not yet been papally confirmed at the time of the coronation; because of the autumn season, the great men of the Empire avoided the long journey from Frankfurt, where the election had taken place anyway, to Aachen and Cologne. In addition, the king sympathized with Protestant ideas and found relic homages out of date. All subsequent imperial coronations also took place in Frankfurt; as coronator henceforth celebrated the archbishop of Mainz.[80] Thus, this relocation detrimented the centuries-old narrative of the "Holy Cologne."[81] Not coincidentally, from 1567, Cologne councilors built a city hall loggia, which in its Renaissance style deliberately cited the triumphal arch architecture of Roman antiquity, thus recalling the historical greatness of Cologne.[82]

Regulation of the Rhine

[edit]Since the High Middle Ages, the people of Cologne had observed with concern that the Rhine began to shift its river bed on the right bank near Poll. Floods and ice flows broadened this deviation. To prevent an eastern breach of the Rhine between Poll and Deutz, Cologne planned to fortify the bank with the so-called “Poll Heads” (Poller Köpfe), but it was not until 1557 that the council was able to reach an agreement with the archbishop on the measures. In 1560, the large-scale project was started and continued for more than 250 years. In total, three heavy headlands were built as shore fortification. In addition to hundreds of ships laid aground, willow plantings and groynes were brought in to prevent deviations in the course of the river. Iron-reinforced oak logs - weighted down with basalt boulders and connected by heavy crossbeams - were driven into the river bottom. The northern headland is said to have had a length of 1500 meters.[83]

Map based city administration

[edit]

The religious and economic unrest afflicting the Spanish Netherlands from 1566 onward was observed in Cologne with apprehensiveness.[84] The Spanish general Duke of Alba, sent to Brussels in 1567 as the new governor-general of the Spanish crown, sought to quell Flemish discontent with draconian measures and military force. Because of the tensions, many refugees left Antwerp and settled in Cologne; among the most illustrious were Jan Rubens, father of the subsequently famous painter Peter Paul, and Anna of Saxony, wife of William of Orange, who eventually became governor of the united Dutch provinces. Duke Alba therefore also exerted considerable pressure on the city of Cologne to keep refugees out of the Rhine city and to secure military transit routes to the Habsburg possessions in southern Europe.[85]

The Cologne Council endeavored to meet Spanish demands for improved city administration and a rigorous attitude toward refugees. To this end, as a modern administrative measure of the time, the council had a detailed Bird's-eye view of the city drawn up, to enhance the mastery of inhabitants and immigrants.[86] The cartographer Arnold Mercator drew up the plan at a scale of 1:2450, striving for a work that satisfied cartographic-scientific standards; the map was based on a comparatively accurate survey of the city's topography and showed the building tracts in the aim to create a spatial effect with a skillful mixture of elevation and bird's-eye view. Given its detailed and true-to-scale representation, the so-called Mercator Plan is considered today to be the first reliable city plan of Cologne[87] and is perceived as one of the first ever cartographically correct city maps.[88]

Futile pacification efforts

[edit]

The economic region of the Spanish Netherlands, so foundational for Cologne's prosperity, did not come to rest in the 1570s. In 1575, the Spanish king Philipp II had to declare a state bankruptcy; the Spanish occupation troops of the Netherlands remained without pay. In 1576, they went marauding through Flanders and, looting, wreaked havoc in the city of Antwerp. This caused proverbial horror as the Spanish Fury and strengthened the resistance of the Flemings and Dutch against the Spanish crown. In the course of the riots, the newly built Hanseatic Kontor in Antwerp was also looted several times. The merchants of Cologne tried in vain to be compensated for the damage; in the following years, the Kontor lost its economic importance.[89]

The Union of Arras, agreed in January 1579 and followed promptly by the Union of Utrecht, marked the arising separation of the Spanish Netherlands, from which the states of the Netherlands and Belgium would ultimately emerge. The Union of Utrecht, dominated by the Province of Holland, was also joined by almost all the Brabant and Flanders cities. To pacify the disputes in the provinces, which formally still were part of the Holy Roman Empire, Emperor Rudolf II, the brother-in-law of the Spanish king, sought a negotiated settlement. The so-called Pacification Day took place in Cologne from April to November 1579, because the imperial city, as a strategically important metropolis, could be accepted as a neutral location and provide the necessary infrastructure for the delegations. The representatives of the Netherlands, the emperor and the Spanish crown were accommodated in the city palaces of Cologne's councillors. The negotiations themselves took place in the City hall called Gürzenich. However, the conferences ended without any agreement.[90] Today, Cologne's Pacification Day is understood as the starting point for the emergence of an independent Dutch state.[91] How vitally the Dutch disputes affected Cologne's interests got evidence in 1580, when Dutch warships came up the Rhine and advanced as far as Cologne. The coordinated efforts of a fleet of Rhenish electors promptly drove off the invaders.[92] Overall, developments were unfavorable to Cologne's economic interests. The unrest severely disrupted Cologne's trade routes to Flanders; in addition, the Dutch were able to control sea access to the Rhine. Both gravely impeded Cologne's trade flows and brought Cologne's trade with England to an almost complete standstill.[93]

Early modern period

[edit]

In the beginning of Early modern period, Reformation continuously tempted the leading classes of Cologne. In 1582, Archbishop Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg converted to the Reformed faith and attempted to reform practices in the city's churches. This was violently opposed by the Wittelsbachs, leading to the Cologne War. The city's population, following the lead of the cathedral clergy, generally preferred the influence of the Pope in Rome to the Archbishop on their doorstep and so the city was spared the worst of the devastation inflicted on the surrounding towns and countryside.

From 1583 to 1761, all ruling archbishops came from the Wittelsbach dynasty. As powerful electors, the archbishops repeatedly challenged Cologne's free status during the 17th and 18th centuries, resulting in complicated legal affairs, which were handled by diplomatic means, usually to the advantage of the city.

In the period of the persecution of witches (1435–1655), 37 people were executed in Cologne, mostly during the reign of Archbishop Ferdinand of Bavaria in the years 1626 to 1631. One of those executed was Katharina Henot, the first known female postmaster of Germany and an influential citizen. She apparently fell victim to a conspiracy of her enemies among the city authorities after proceedings which were flawed according to the laws of the period.

Modern history

[edit]Napoleonic and Prussian period

[edit]

Cologne Cathedral

The French Revolutionary Wars resulted in the occupation of Cologne and the Rhineland in 1794. In the following years the French consolidated their presence. In 1798 the city became an arrondissement in the newly created Département de la Roer. In the same year the University of Cologne was closed. In 1801 all citizens of Cologne were granted French citizenship. In 1804 Napoléon Bonaparte visited the city together with his wife Joséphine de Beauharnais. The French occupation ended in 1814, when Cologne was occupied by Prussian and Russian troops. In 1815 Cologne and the Rhineland were allocated to Prussia.

Weimar Republic

[edit]From the end of World War I until 1926, Cologne was occupied by the British Army of the Rhine under the terms of the armistice and the subsequent Peace Treaty of Versailles.[94]

In contrast to the harsh measures taken by French occupation troops, the British acted with more tact towards the local population. Konrad Adenauer, mayor of Cologne from 1917 until 1933 and a future West German chancellor, acknowledged the political impact of this approach, especially that the British opposed French plans for a permanent Allied occupation of the Rhineland.

The demilitarization of the Rhineland required the fortifications to be dismantled. This was taken as an opportunity to create two green belts (Grüngürtel) around the city by converting the fortifications and their surroundings, which had been kept clear for artillery, into large public parks. This project was completed in 1933.

In 1919 Cologne University, closed by the French in 1798, was founded anew. It was considered a substitute for the German University of Strasbourg, which became part of France along with the rest of Alsace. Cologne prospered during the Weimar Republic and progress was made especially in governance, city planning and social affairs. Social housing projects were considered exemplary and were copied by other German cities.

As Cologne competed to host the Olympics, a modern sports stadium was erected at Müngersdorf. Early in the 1920s civil aviation was permitted once more, and Cologne Butzweilerhof Airport soon became a hub for national and international air traffic, second in Germany only to Berlin Tempelhof Airport.

Nazi Germany

[edit]At the beginning of Nazi Germany, Cologne was considered difficult by the Nazis because of deep-rooted communist and Catholic influences in the city. The Nazis were always struggling for control of the city.

Local elections on 13 March 1933 resulted in the Nazi Party winning 39.6% of the vote, followed by the catholic Zentrum Party with 28.3%, the Social Democratic Party of Germany with 13.2%, and the Communist Party of Germany with 11.1%. One day later, on 14 March, Nazi followers occupied the city hall and took over government. Communist and Social Democratic members of the city assembly were imprisoned, and Mayor Adenauer was dismissed.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, the Jewish population of Cologne was about 20,000. By 1939, 40% of the city's Jews had emigrated. The vast majority of those who remained had been deported to concentration camps by 1941. The trade fair grounds next to the Deutz train station were used to herd the Jewish population together for deportation to the death camps and for disposal of their household goods by public sale. On Kristallnacht in 1938, Cologne's synagogues were desecrated or set on fire.[95]

It was planned to rebuild a large part of the inner city, with a main road connecting the Deutz station and the main station, which was to be moved from next to the cathedral to an area adjacent to today's university campus, with a huge field for rallies, the Maifeld, next to the main station. The Maifeld, between the campus and the Aachener Weiher artificial lake, was the only part of this over-ambitious plan to be realized before the start of the war. After the war, the remains of the Maifeld were buried with rubble from bombed buildings and turned into a park with rolling hills, which was christened Hiroshima-Nagasaki-Park in August 2004 as a memorial to the victims of the nuclear bombs of 1945. An inconspicuous memorial to the victims of the Nazi regime is situated on one of the hills.

On the night of 30–31 May 1942, Cologne was the target for the first 1,000 bomber raid of the war. Between 469 and 486 people, around 90% of them civilians, were reported killed, more than 5,000 were injured, and more than 45,000 lost their homes. It was estimated that up to 150,000 of Cologne's population of around 700,000 left the city after the raid. The Royal Air Force lost 43 of the 1,103 bombers sent. By the end of World War II, 90% of Cologne's buildings had been destroyed by Allied aerial bombing raids, most of them flown by the RAF.

On 10 November 1944, a dozen members of the anti-Nazi Ehrenfeld Group were hanged in public. Six of them were 16-year-old boys of the Edelweiss Pirates youth gang, including Barthel Schink; Fritz Theilen survived.

The bombings continued and people moved out. By May 1945 only 20,000 residents remained out of 770,000.[96]

The outskirts of Cologne were reached by US troops on 4 March 1945. The inner city on the left bank of the Rhine was captured in half a day on 6 March 1945, meeting only minor resistance. Because the Hohenzollernbrücke was destroyed by retreating German pioneers, the boroughs on the right bank remained under German control until mid-April 1945.[97]

Postwar Cologne

[edit]Although Cologne was larger than its neighbors, Düsseldorf was chosen as the political capital of the newly established Federal State of North Rhine-Westphalia, and Bonn as the (provisional) capital of the Federal Republic. Cologne benefited from being sandwiched between the two important political centers of West Germany by becoming home to a large number of federal agencies and organizations. After reunification in 1990, a new situation has been politically co-ordinated[clarification needed] with the new federal capital, Berlin.

In 1945 architect and urban planner Rudolf Schwarz called Cologne the "world's greatest heap of debris". Schwarz designed the 1947 reconstruction master plan, which called for the construction of several new thoroughfares through the downtown area, especially the Nord-Süd-Fahrt (North-South-Drive). The plan took into consideration that even shortly after the war a large increase in automobile traffic could be anticipated. Plans for new roads had already evolved to some extent under the Nazi administration, but construction became easier now that the majority of downtown lots were undeveloped. The destruction of the famous twelve Romanesque churches, including St. Gereon's Basilica, Great St. Martin, St. Maria im Kapitol and about a dozen others during World War II, meant a tremendous loss of cultural substance to the city. The rebuilding of these churches and other landmarks like the Gürzenich was not undisputed among leading architects and art historians at that time, but in most cases, civil intention[clarification needed] prevailed. The reconstruction lasted until the 1990s, when the Romanesque church of St. Kunibert was finished.

It took some time to rebuild the city. In 1959 the city's population reached pre-war numbers again. Afterwards the city grew steadily, and in 1975 the number exceeded one million inhabitants for about a year. The population stayed just below a million for the next 35 years, before again surpassing the million inhabitant mark in 2010.

In the 1980s and 1990s Cologne's economy prospered from two factors. First, the steady growth in the number of media companies in both the private and the public sector. Catering especially to these companies is the newly developed Media Park, which creates a strongly visual focal point in downtown Cologne and includes the KölnTurm (Cologne Tower), one of Cologne's most prominent highrises. Secondly, a permanent improvement in traffic infrastructure, which makes Cologne one of the most easily accessible metropolitan areas in Central Europe.

Due to the economic success of the Cologne Trade Fair, the city arranged a large extension to the fair site in 2005. The original buildings, which date back to the 1920s, are rented out to RTL, Germany's largest private broadcaster, as their new corporate headquarters.

Cologne was at the centre of the 2015-16 New Year's Eve sexual assaults in Germany. A controversy started after Muslims in Cologne sought to build the Cologne Central Mosque, which was completed in 2017.[98]

Most important for the history of Cologne since the Middle Ages is the Cologne City Archive, which was the largest in Germany. Its building collapsed during the construction of an extension to the underground railway system on 3 March 2009.[99]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Gerhard Curdes, Markus Ulrich: Die Entwicklung des Kölner Stadtraumes, Der Einfluß von Leitbilder und Innovationen auf die Form der Stadt. Dortmund 1997, p. 73ff.

- ^ E. Buringh, 2020, "European urban population, 700 - 2000", https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-xzy-u62q, DANS Data Station Social Sciences and Humanities, V1

- ^ E. Buringh, 2020, "European urban population, 700 - 2000," https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-xzy-u62q, DANS Data Station Social Sciences and Humanities, V1

- ^ Werner Meyer-Barkhausen: Das große Jahrhundert Kölnischer Kirchenbaukunst 1150 bis 1250, Cologne 1952

- ^ J. Bradford De Long, Andrei Shleifer: Princes and Merchants: European City Growth before the Industrial Revolution, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 4274, Cambridge, February 1993

- ^ Joachim Deeters: Vom Bau der Großen Mauer um Köln 1180, Neue Überlegungen zu einem alten Problem der Kölner Stadtgeschichte; in: Geschichte in Köln, Zeitschrift für Stadt- und Regionalgeschichte 69 (2022), pp. 33-49, here p. 49

- ^ E. Buringh, 2020, "European urban population, 700 - 2000", https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-xzy-u62q, DANS Data Station Social Sciences and Humanities, V1

- ^ E. Buringh, 2020, "European urban population, 700 - 2000," https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-xzy-u62q, DANS Data Station Social Sciences and Humanities, V1

- ^ Fernand Braudel: The perspective of the world, London 1984, p. 143

- ^ E. Buringh, 2020, "European urban population, 700 - 2000", https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-xzy-u62q, DANS Data Station Social Sciences and Humanities, V1

- ^ E. Buringh, 2020, "European urban population, 700 - 2000," https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-xzy-u62q, DANS Data Station Social Sciences and Humanities, V1

- ^ E. Buringh, 2020, "European urban population, 700 - 2000," https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-xzy-u62q, DANS Data Station Social Sciences and Humanities, V1

- ^ J.C. Russell, "Late Ancient and Medieval Population", in Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 48, part 3, table 89.

- ^ Synagogen-Gemeinde Köln Archived 2008-10-15 at the Wayback Machine (sgk.de) "älteste ... Jüdische ... Gemeinde nördlich der Alpen (urkundlich erwähnt seit 321 n. d. Z.)" ("the oldest Jewish community north of the Alps, recorded since 321 CE")

- ^ Harry de Quetteville. "History of Cologne". The Catholic Encyclopedia, November 28, 2009.

- ^ James Westfall Thompson, Economic and Social History of Europe in the Later Middle Ages (1300–1530) (1931), pp. 146–79

- ^ Paul Strait, Cologne in the Twelfth Century (1974)

- ^ Joseph P. Huffman, Family, Commerce, and Religion in London and Cologne (1998) covers from 1000 to 1300.

- ^ David Nicholas, The Growth of the Medieval City: From Late Antiquity to the Early Fourteenth Century (1997), pp. 69–72, 133–42, 202–20, 244–45, 300–307

- ^ Liber Chronicarum

- ^ Wolfgang Herborn, Carl Dietmar: Köln im Spätmittelalter 1288-1512/13, Cologne 2019, p. 182ff.

- ^ Wolfgang Herborn, Carl Dietmar: Köln im Spätmittelalter 1288-1512/13, Cologne 2019, p. 228f

- ^ Christian Hillen, Peter Rothenhöfer, Ulrich Soénius: Kleine illustrierte Wirtschaftsgeschichte der Stadt Köln. Cologne 2013, p. 90 f.

- ^ Gerald Chaix: Köln im Zeitalter von Reformation und Katholischer Reform 1512/13-1610, Cologne 2022, pp. 47ff

- ^ Christian Hillen, Peter Rothenhöfer, Ulrich Sóenius: Kleine illustrierte Wirtschaftsgeschichte der Stadt Köln, Cologne 2013, p. 73

- ^ Wolfgang Herborn, Carl Dietmar: Köln im Spätmittelalter 1288-1512/13, Cologne 2019, p. 213ff.

- ^ Rheinische Geschichte: Arnold von Siegen

- ^ Wolfgang Herborn, Carl Dietmar: Köln im Spätmittelalter 1288-1512/13, Cologne 2019, pp. 184, 191

- ^ Wolfgang Herborn, Carl Dietmar: Köln im Spätmittelalter 1288-1512/13, Cologne 2019, pp. 195ff

- ^ Wolfgang Herborn, Carl Dietmar: Köln im Spätmittelalter 1288-1512/13, Cologne 2019, pp. 192ff

- ^ Wolfgang Herborn, Carl Dietmar: Köln im Spätmittelalter 1288-1512/13, Cologne 2019, pp. 187-191

- ^ Gerald Chaix: Köln in der Zeit von Reformation und Katholischer Reform, Cologne 2022, p. 81ff

- ^ Deeters, Helmrath (ed.): Quellen zur Geschichte der Stadt Köln. Volume II, p. 1 ff. and p. 238 ff.

- ^ Rüdiger Marco Booz: Kölner Dom, die vollkommene Kathedrale, Petersberg 2022, p. 142.

- ^ Hans Koch: Geschichte des Seidengewerbes in Köln vom 13. bis zum 18. Jahrhundert; Leipzig 1907, p. 67ff

- ^ Gérald Chaix: Köln im Zeitalter von Reformation and Katholischer Reform, 1512/13-1610, Cologne 2022, p. 57

- ^ Rheinische Geschichte: Fygen Lutzenkirchen

- ^ Wolfgang Herborn, Carl Dietmar: Köln im Spätmittelalter 1288-1512/13, Cologne 2019, p. 41

- ^ Maria Männig: Review of: Marita Bombeck / Gudrun Sporbeck: Kölner Bortenweberei im Mittelalter. Corpus Kölner Borten, Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner 2012, in: sehepunkte 15 (2015), no. 10 [15.10.2015]

- ^ Gérald Chaix: Köln im Zeitalter von Reformation und Katholischer Reform, 1512/13-1610, Cologne 2022, pp. 218, 222

- ^ Hans Koch: Geschichte des Seidengewerbes in Köln vom 13. bis zum 18. Jahrhundert; Leipzig 1907, p. 70

- ^ Hiltrud Kier, Frank Günter Zehnder: Lust und Verlust, Kölner Sammler zwischen Trikolore und Preußenadler, Cologne 1995, p. 13.

- ^ Thesy Teplitzky: Geld, Kunst, Macht: eine Kölner Familie zwischen Mittelalter und Renaissance. Cologne 2009, p. 24.

- ^ Wolfgang Schmid: Kölner Sammler im Renaissancezeitalter; in: Hiltrud Kier, Frank Günter Zehnder: Lust und Verlust, Kölner Sammler zwischen Trikolore und Preußenadler, Cologne 1995, pp. 15-31, here pp. 15ff.

- ^ Udo Mainzer: Kleine illustrierte Architekturgeschichte der Stadt Köln, Cologne 2017, p. 73.

- ^ Udo Mainzer: Kleine illustrierte Architekturgeschichte der Stadt Köln, Cologne 2017, p. 63f.

- ^ Brigitte Corley: Maler und Stifter des Spätmittelalters in Köln 1300-1500, Kiel 2009, p. 35ff.

- ^ Rüdiger Marco Booz: Kölner Dom, die vollkommene Kathedrale, Petersberg 2022, p. 142.

- ^ Rainer Budde, Roland Krischel (eds.): Genie ohne Namen. Der Meister des Bartholomäus-Altars, Cologne 2001.

- ^ Udo Mainzer: Kleine illustrierte Kunstgeschichte der Stadt Köln, Cologne 2015, p. 74.

- ^ Wolfgang Schmitz: Eine Verlagsstadt von europäischem Rang: Köln im 15. und 16. Jahrhundert; in: Dagmar Täube, Miriam Fleck (eds.): Glanz und Größe des Mittelalters: Kölner Meisterwerke aus den großen Sammlungen der Welt, Cologne 2012, pp. 220-231, here p. 222

- ^ Wolfgang Schmitz: Die Überlieferung deutscher Texte im Kölner Buchdruck des 15. und 16. Jahrhunderts. Habil.-Schrift Cologne 1990, p. 439

- ^ Gérald Chaix: Köln im Zeitalter von Reformation und Katholischer Reform 1512/13-1688, Cologne 2021, pp. 170, 172, 174

- ^ Gérald Chaix: Köln im Zeitalter von Reformation und Katholischer Reform 1512/13-1688, Cologne 2021, pp. 168, 175

- ^ Hans Lülfing (1980), "Koelhoff, Johann d. J.", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 12, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 319–319; (full text online)

- ^ NDB - Johannes Pfefferkorn

- ^ Rüdiger Marco Booz: Kölner Dom, die vollkommene Kathedrale, Petersberg 2022, p. 131

- ^ Gérald Chaix: Köln in der Zeit von Reformation und katholischer Reform, 1512/13-1620, Cologne 2022, pp. 156f, 187, 397

- ^ Gerald Chaix: Köln in der Zeit von Reformation und katholischer Reform 1512/13-1610, Cologne 2022, p. 93ff

- ^ Hansgeorg Molitor: Das Erzbistum Köln im Zeitalter der Glaubenskämpfe (1515-1688), Cologne 2008, p. 159ff

- ^ Rüdiger Marco Booz: Kölner Dom, die vollkommene Kathedrale, Petersberg 2022, pp. 134, 141

- ^ Hansgeorg Molitor: Das Erzbistum Köln im Zeitalter der Glaubenskämpfe (1515-1688), Cologne 2008, pp. 159ff

- ^ Hansgeorg Molitor: Das Erzbistum Köln im Zeitalter der Glaubenskämpfe (1515-1688), Cologne 2008, pp. 161-176

- ^ Fernand Braudel: The perspective of the world, London 1984, p. 143

- ^ Floris Prims: Antwerpen door de eeuwen heen, Antwerp 1951, p. 373

- ^ J.A. Houtte: Anvers aux XVe et XVIe siècles : expansion et apogée. In: Annales. Economies, sociétés, civilisations. 16e année, N. 2, 1961; pp. 248-278, here p. 249

- ^ Gerald Chaix: Köln in der Zeit von Reformation und katholischer Reform 1512/13-1610, Cologne 2022, p. 217ff

- ^ Isabelle Kirgus: Renaissance in Köln, Architektur und Ausstattung 1520-1620, Bonn 2004.

- ^ Thesy Teplitzky: Geld, Kunst, Macht: eine Kölner Familie zwischen Mittelalter und Renaissance. Cologne 2009, p. 106ff.

- ^ Rüdiger Marco Booz: Kölner Dom, die vollkommene Kathedrale, Petersberg 2022, p. 140.

- ^ Isabelle Kirgus: Die Rathauslaube in Köln 1569-1573, Architektur und Antikenrezeption, Bonn 2003.

- ^ Udo Mainzer: Kleine illustrierte Kunstgeschichte der Stadt Köln, Cologne 2015, p. 93.

- ^ Miriam Verena Fleck: Köln - "... so berühmt und von so hohem Rufe, gewissermaßen einzigartig in deutschen Landen ..."; in: Dagmar Täube, Miriam Verena Fleck (eds.): Glanz und Größe des Mittelalters, Kölner Meisterwerke aus den großen Sammlungen der Welt, Munich 2011, pp. 20-36, here p. 29.

- ^ Fernand Braudel: The perspective of the world, London 1984, p. 143

- ^ Christian Hillen, Peter Rothenhöfer, Ulrich Soénius: Kleine Illustrierte Wirtschaftsgeschichte der Stadt Köln, Cologne 2013, p. 72

- ^ Christian Hillen, Peter Rothenhöfer, Ulrich Soénius: Kleine Illustrierte Wirtschaftsgeschichte der Stadt Köln, Cologne 2013, p. 96

- ^ Gerald Chaix: Köln im Zeitalter der Reformation und katholischer Reform 1512/13-1610, Cologne 2022, p. 47ff

- ^ Rheinische Geschichte: Heinrich Sudermann

- ^ Christian Hillen, Peter Rothenhöfer, Ulrich Soénius: Kleine Illustrierte Wirtschaftsgeschichte der Stadt Köln, Cologne 2013, pp. 80, 88

- ^ Hansgeorg Molitor: Das Erzbistum Köln im Zeitalter der Glaubenskämpfe (1515-1688), (Geschichte des Erzbistums Köln Band 3), Cologne 2008, p. 181.

- ^ Rüdiger Marco Booz: Kölner Dom, die vollkommene Kathedrale, Petersberg 2022, p. 147.

- ^ Isabelle Kirgus: Die Rathauslaube in Köln 1569-1573, Architektur und Antikenrezeption, Bonn 2003.

- ^ Niedrigwasser macht’s möglich - Entdeckung am Kölner Rheinufer. In: Deutsche Stiftung Denkmalschutz (ed.): Monumente online. May 2006.

- ^ Gérald Chaix: Köln im Zeitalter von Reformation und Katholischer Reform 1512/13-1610, Cologne 2022, p. 242

- ^ Magnus Ressel: Der Herzog von Alba und die deutschen Städte im Westen des Reiches 1567–1573. Köln, Aachen und Trier im Vergleich; in: Andreas Rutz (ed.), Krieg und Kriegserfahrung im Westen des Reiches 1568-1714, Göttingen 2016, pp. 31-63, here p. 61

- ^ Gérald Chaix: Köln im Zeitalter von Reformation und Katholischer Reform 1512/13-1610, Cologne 2022, pp. 198f

- ^ Peter Noelke: Entdeckung der Geschichte, Arnold Mercators Stadtansicht von Köln. In: Renaissance am Rhein, Katalog zur Ausstellung im LVR-Landesmuseum Bonn, 2010/2011, Munich 2010, p. 251

- ^ Stephan Hoppe: Die vermessene Stadt. Kleinräumige Vermessungskampagnen im Mitteleuropa des 16. Jahrhunderts und ihr funktionaler Kontext. In: Ingrid Baumgärtner (Ed.): Fürstliche Koordinaten. Landesvermessung und Herrschaftsvisualisierung um 1600, Leipzig 2014, p. 251–273, here p. 269

- ^ Rhenish History: Heinrich Sudermann

- ^ Gérald Chaix: Cologne in the Age of Reformation and Catholic Reform 1512/13-1610, Cologne 2022, p. 243

- ^ Thomas P. Becker: Der Kölner Pazifikationskongress von 1579 und die Geburt der Niederlande, in: Michael Rohrschneider (ed.): Frühneuzeitliche Friedensstiftung in landesgeschichtlicher Perspektive, Cologne 2019, pp. 99-119, here p. 118

- ^ Gérald Chaix: Cologne in the Age of Reformation and Catholic Reform 1512/13-1610, Cologne 2022, p. 244

- ^ Christian Hillen, Peter Rothenhöfer, Ulrich Soénius: Kleine Illustrierte Wirtschaftsgeschichte der Stadt Köln, Cologne 2013, p. 78

- ^ "Cologne Evacuated", Time, February 15, 1926

- ^ Horst Matzerath: Köln in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus. In: Peter Fuchs (Hrsg.): Chronik zur Geschichte der Stadt Köln.

- ^ Richard Overy, The Bombers and the Bombed: Allied Air War Over Europe 1940-1945 (2014) p 304

- ^ "Trotz Durchhalteparolen wenig Widerstand – Die US-Armee nimmt Köln ein" [Minor restistance despite rallying calls – the US-army captures Cologne]. Sixty years ago [Vor 60 Jahren] on www.wdr.de (in German). Westdeutscher Rundfunk. 7 March 2005. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- ^ Harry de Quetteville. "Huge mosque stirs protests in Cologne". Telegraph, June 26, 2007.

- ^ Resistance : subjects, representations, contexts. Butler, Martin, Dr.,, Mecheril, Paul, 1962-, Brenningmeyer, Lea. Bielefeld. 30 June 2017. p. 124. ISBN 978-3-8394-3149-8. OCLC 1011461726.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link)

Further reading

[edit]- "Cologne", The Rhine from Rotterdam to Constance, Leipsic: Karl Baedeker, 1882, OCLC 7416969

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 697–699.

- "Cologne", The Rhine, including the Black Forest & the Vosges, Leipzig: Karl Baedeker, 1911, OCLC 21888483

External links

[edit]- Edicts of the "Kurfürstentum" of Cologne, 1461–1816 online

- Map of the Archbishopric of Cologne in 1789

- Colonia Agrippina (Present-Day Cologne) Accurately Described in the Year 1571

- Cologne History Society

- Edicts of the Electorate of Cologne (with the Duchy of Westphalia and Vest Recklinghausen) (1461–1816) (Slg. Scotti online)

- Statutes of the city of Cologne – manuscripts from the mid-15th century

- Deed of the city of Cologne (Bürgermeister and Schöffen) from 1159, with city seal,"digitalised image". Photograph Archive of Old Original Documents (Lichtbildarchiv älterer Originalurkunden). University of Marburg.

- Comprehensive description of the history of the city

- Nazi documentation centre for the city of Cologne

- Landschaftsverband Rheinland: Portal Rheinische Geschichte