Immigration to Germany

| German citizenship and immigration |

|---|

| Immigration |

| Citizenship |

| Agencies |

| History |

Immigration to Germany, both in the country's modern borders and the many political entities that preceded it, has occurred throughout the country's history. Today, Germany is one of the most popular destinations for immigrants in the world, with well over 1 million people moving there each year since 2013.[1] As of 2019, around 13.7 million people living in Germany, or about 17% of the population, are first-generation immigrants.[2]

Even before Germany's formal founding in 1871, its predecessor states, such as the Holy Roman Empire and the German Confederation, were common destinations for the persecuted or migrant workers. Early examples include Protestants seeking religious freedom and refugees from the partitions of Poland. Jewish migrants, mostly from Eastern Europe, was also significant in successive waves. In the 20th century, rising antisemitism and xenophobia resulted in the mass emigration of German Jews and culminated in the Holocaust, in which almost all remaining German Jews and many other religious or ethnic groups, such as German Roma, were systematically murdered. In the decades since, Germany has experienced renewed immigration, particularly from Eastern and Southern Europe, Turkey and the Middle East.[3] Since 1990, Germany has consistently ranked as one of the five most popular destination countries for immigrants in the world.[4] According to the federal statistics office in 2016, over one in five Germans has at least partial roots outside of the country.[5]

In modern Germany, immigration has generally risen and fallen with the country's economy.[6] The economic boom of the 2010s, coupled with the elimination of working visa requirements for many EU citizens, brought a sustained inflow from elsewhere in Europe.[7] Separate from economic trends, the country has also seen several distinct major waves of immigration. These include the forced resettlement of ethnic Germans from eastern Europe after World War II, the guest worker programme of the 1950s–1970s, and ethnic Germans from former Communist states claiming their right of return after the breakup of the Soviet Union.[8] Germany also accepted significant numbers of refugees from the Yugoslav wars in the 1990s and the Syrian civil war in the 2010s.

Motivated in part by low birth rates and labour shortages, German government policy towards immigration has generally been relatively liberal since the 1950s,[9] although conservative politicians resisted the normalization of Germany as a country of immigrants and citizenship laws accordingly remained relatively restrictive until the mid-2000s. A major reform of immigration law in 2005 saw the state commit, for the first time, resources to the integration of newcomers and significantly liberalised the labour market for skilled professionals while restricting it for unskilled labourers.[10] Smaller immigration reforms in 2009, 2012 and 2020 contributed to the broad trend of liberalisation.[10] The 2021 federal elections saw the formation of a center-left government which promised to reform immigration law.[11] In 2023, the coalition began implementing a series of reforms including the Skilled Workers Immigration Act (in German, Fachkräfteeinwanderungsgesetz, or FEG)[12] that among other things eased requirements for foreign workers,[13] relaxed naturalization requirements[14] and legalized multiple citizenship.[14]

History of immigration to Germany

[edit]Pre-unification

[edit]The Counter-Reformation in the 16th and 17th centuries led large numbers of Protestants to settle in Protestant — or at least religiously tolerant — principalities and cities of the Holy Roman Empire, much of which would later become Germany. According to one estimate, a total of 100,000 Protestants moved from Habsburg lands to what is now southern and central Germany in the 17th century.[3]

Large numbers of Huguenots also fled France after the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre in 1572, around 40,000 of whom settled in what is now Germany. Although many returned to France after the 1598 Edict of Nantes, which proclaimed a policy of religious tolerance towards Huguenots, repeated waves of conflict and persecution over the next few centuries spurred new waves of emigration. Brandenburg-Prussia, Hesse-Kassel, Brandenburg-Bayreuth, and Hanover were major destinations of Huguenots during this time.[3]

Several thousand English and Scottish Presbyterians also fled the violent reign of Mary Tudor; many settled in Frankfurt. Many Dutch Calvinists settled in northwestern Germany after the Dutch Revolt.[3]

After World War II until reunification (1945–1990)

[edit]Forced emigration of ethnic Germans from eastern and central Europe

[edit]Towards the end of World War II, and in its aftermath, up to 12 million refugees of ethnic Germans, so-called "Heimatvertriebene" (German for "expellees", literally "homeland displaced persons") were forced to migrate from the former German areas, as for instance Silesia or East Prussia, to the new formed States of post-war Germany and Allied-occupied Austria, because of changing borderlines in Europe.[15][16]

Guest worker programs

[edit]

Due to a shortage of laborers during the Wirtschaftswunder ("economic miracle") in the 1950s and 1960s, the West German government signed bilateral recruitment agreements with Italy in 1955, Greece in 1960, Turkey in 1961, Morocco in 1963, Portugal in 1964, Tunisia in 1965 and Yugoslavia in 1968. These agreements allowed German companies to recruit foreign citizens to work in Germany.[17] The work permits were at first issued for a duration of two years, after which the recruited workers were supposed to return to their home countries. However, many companies repeatedly renewed the work permits;[18] some of the bilateral treaties were even updated to give workers permanent residency upon arrival.[19] As a result, even though many did ultimately return to their countries of origin, several million of the recruited workers and their families ended up settling in Germany permanently. Nevertheless, the government continued to encourage the public perception of the arriving immigrants as temporary guest workers (Gastarbeiter) and for many years made little provision for their integration into German society.[20]

East Germany set up similar foreign recruitment schemes, although at much smaller scales and exclusively with other socialist states. Most foreign workers recruited to East Germany, known locally as Vertragsarbeiter, came from North Vietnam (ca. 60,000),[21] Cuba (30,000),[22] Mozambique (21,000)[23] and Angola (6,000).[24] The government portrayed East Germany as a post-racial society and called the foreign workers socialist "friends" who would learn skills which could then be applied in their home countries. In reality, racism and exploitation were widespread.[25] The workers were generally strictly segregated from locals and did menial work that locals refused to do.[3] Considerable portions of their paychecks were often diverted to their home governments, making their livelihoods precarious.[26] Female Vertragsarbeiter were not allowed to become pregnant during their stay. If they did, they were forced to have an abortion[27][28] or faced deportation.

Following German reunification in 1990, many of the roughly 90,000 foreign workers living in what had been East Germany had no legal status as immigrant workers under the Western system. Consequently, many faced deportation or premature termination of residence and work permits, as well as open discrimination in the workplace and racism in everyday life. The vast majority ultimately returned to their home countries.[25]

Immigration from East Germany to West Germany

[edit]During the 1980s, a small but steady stream of East Germans immigrating to the West (Übersiedler) had begun with the gradual opening of the Eastern bloc. In 1990, the year of German reunification, the number swelled to 389,000.[29]

Aussiedler

[edit]

As Eastern bloc countries gradually began to open their borders in the 1980s, large numbers of ethnic Germans from these countries began to move to Germany. German law at the time recognized an almost unlimited right of return for people of German descent,[30] of whom there were several million in the Soviet Union, Poland and Romania.[31] Germany initially received around 40,000 per year. In 1987, the number doubled, in 1988 it doubled again and in 1990 nearly 400,000 immigrated. Upon arrival, ethnic Germans became citizens at once according to Article 116 of the Basic Law, and received financial and many social benefits, including language training, as many did not speak German. Social integration was often difficult, even though ethnic Germans were entitled to German citizenship, but to many Germans they did not seem German. In 1991, restrictions went into effect, in that ethnic Germans were assigned to certain areas, losing benefits if they moved. The German government also encouraged the estimated several million ethnic Germans living in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe to remain there. From 1993 to 1999, the German government established a cap limiting ethnic German immigration to 220,000 people per year, which was later lowered to 100,000.[32][29] In total, more than 4.5 million ethnic Germans moved to Germany between 1990 and 2007.[33]

Refugees

[edit]

And in parallel, a third stream of immigration starting in the mid-1980s were war refugees, of which West Germany accepted more than any other West European country due to a nearly unqualified right to asylum. Around 300,000 Iranians fled from persecution in the wake of the Iranian Revolution between 1979 and 1986 alone.[34] Notable numbers of asylum seekers came from Turkey after a military coup in 1980 and, separately, due to ongoing persecution of Turkish Kurds in the country.[35] Several thousand people also sought refuge in Germany from the Lebanese Civil War.[36]

1990–present

[edit]Yugoslav refugees

[edit]

Due to the outbreak of the Yugoslav Wars in 1991, large numbers of refugees headed to Germany and other European countries.[37] Between 1990 and 1992 nearly 900,000 people sought asylum in a united Germany.[29] In 1992 Germany admitted almost 70 percent of all asylum seekers registered in the European Community.[38] By comparison, only about 100,000 people sought asylum in the U.S in the same year.[39] The growing numbers of asylum seekers led the Bundestag to significantly curtail the previously unqualified right to asylum in Germany, which former German refugees had "held sacred because of their reliance on it to escape the Nazi regime" and which required a constitutional amendment.[38] Applications from people entering Germany after passing through other European Community member states, where they theoretically could have already applied for asylum, were now refused, as were applications from nationals of designated safe countries.[40]

Though only about 5 percent of the asylum applications were approved and appeals sometimes took years to be processed, many asylum seekers were able to stay in Germany and received financial and social aid from the government.[29][41]

2015 migration crisis

[edit]Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

In June 2015, new arrivals of asylum seekers, which had been increasing steadily for years,[44] began to rise sharply,[45] driven especially by refugees fleeing wars in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan. An original projection of 450,000 asylum seekers entering Germany for the whole of 2015 was revised upwards to 800,000[46] in August and again in September to over 1 million.[47] The actual final number was 1.1 million;[48] Germany spent about €16 billion (0.5% of GDP) on processing and housing refugees that year.[49]

Most of the refugees entering Western and Central Europe around this time came by land via the so-called "Balkan route." According to an EU law (the Dublin regulation), refugees were required to file asylum claims in the first EU country they set foot in, which for about the 85% of sea arrivals was Greece, and for about 15%, Italy.[50] However, instead of applying there, many attempted to travel to Northern and Western European countries, mostly by traveling through the Balkans and re-entering the EU through Hungary or Croatia. As a result, Hungary registered 150,000 asylum seekers by August 2015. However, the vast majority of these refugees had no desire to remain in Hungary and wanted to move on to Western or Northern Europe, leading to a sizable population of refugees "trapped" in the country.[48] The Hungarian government began to house refugees in camps under squalid conditions.[51] The Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, overwhelmed with the task of processing the sheer number of incoming asylum claims, was unable to prioritize deporting refugees to Hungary and decided to suspend enforcement of the Dublin regulation for Syrian nationals. As a result, refugees in Hungary requested to be allowed leave for Germany; several thousand began making their way across Hungary and Austria towards Germany on foot. Claiming it was no longer able to process asylum claims properly, Hungary began providing buses for refugees to the Austrian border. Responding to a wave of public sympathy in reaction to widely broadcast scenes of police brutality and refugees dying at the hands of smugglers in Hungary, and unable to keep the migrants out of the country without resorting to brutal force, the German and Austrian chancellors, Angela Merkel and Werner Faymann decided to allow the refugees in. The publicity from this decision led hundreds of thousands of people fleeing the Syrian civil war to make for Germany.[48]

Although the number of refugees in formal employment more than tripled between 2016 and 2019,[52] as a group they remain overrepresented in unemployment statistics, which experts ascribe to a combination of red tape and refugees' difficulty in finding housing.[53] Employment among Syrians and Afghans, the two most common nationalities among the 2015–2016 refugee arrivals, rose by 79% and 40%, respectively, between 2017 and 2018.[54]

The 2018 Ellwangen police raid, in which residents of a migrant shelter rioted to prevent police from deporting an asylum seeker whose claim had been deemed invalid, sparked a significant political debate.[55]

In 2015, most Germans were very supportive of the large numbers of refugees arriving in Germany. Then-chancellor Angela Merkel declared in a speech, “Wir schaffen das" (roughly, "we can do this"), which was widely used by news media as well as the public as a defining statement of her policy during the crisis.[56] In 2015, the brunt of the European immigration crisis was placed on Germany when 890,000 refugees crossed the border and applied for asylum, most of them fleeing from the Syrian War. By 2018, 670,000 out of 700,000 Syrians living in Germany immigrated as a result of internal strife and conflict in Syria beginning in 2011.[57] A 2015 survey shows that 46% of the entire German population was facilitating help in some way for refugees. All over, German citizens were creating initiatives and support groups for asylum seekers as well as donating their time to help on-site with refugees. Media helped shape German attitudes as well as put pressure on the government by covering the victims of immigration and by showing individual stories, which humanized them.

The widespread sexual assaults on New Year's Eve of 2015, for which a significant number of suspects were asylum seekers, marked a shift in the tone of media coverage and public opinion towards refugees, though the government noted refugees were, statistically, no more likely than locals to commit crimes.[58]

Between 2010 and 2016, the number of Muslims living in Germany increased from 3.3 million (4.1% of the population) to nearly 5 million (6.1%). The most important factor in the growth of Germany’s Muslim population is immigration.[59]

The intake of refugees in Germany temporarily decreased in the following years, while deportations increased and leveled out at around 20,000.[60]

352,000 people applied for asylum in Germany in 2023, the highest number since 2016, when 722,370 people applied for asylum. People from Ukraine are not included. Most asylum seekers in 2023 were from Turkey, Syria and Afghanistan.[61]

In September 2023, more than 120 boats carrying approximately 7,000 migrants from Africa arrived on the island of Lampedusa within 24 hours.[62] Some of the migrants were relocated to Germany.[63]

Refugees of the Russo-Ukrainian War

[edit]On 24 February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine in a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, which began in Donbas in 2014. In addition to tens of thousands of deaths on both sides, this invasion has caused Europe's largest refugee crisis since World War II, with around 7.5 million Ukrainians fleeing the country and a third of the population displaced. Accordingly, by October 2022, Germany had recorded net immigration of 750,000 people from Ukraine in the first half of 2022, according to the office, responsible for collecting information on German society, economy, and the environment. That influx pushed Germany's population growth to 1%, or about 843,000 people, in the first half of the year.[64] Germany's population rose to an all-time high of 84.3 million people in 2022.[65]

In 2023, 1,933,000 people immigrated to Germany, including 276,000 from Ukraine and 126,000 from Turkey, while 1,270,000 people emigrated. Net immigration to Germany was 663,000 in 2023, down from a record 1,462,000 in 2022.[66]

Migration partnerships

[edit]In September 2024, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and Kenyan President William Ruto signed an agreement that opened the German labor market to up to 250,000 skilled and semi-skilled migrant workers from Kenya.[67] The German government has already signed or is negotiating migration partnerships with Morocco, Nigeria, India, Colombia, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Georgia and Moldova.[68][69] There are concerns about a brain drain with professionals like doctors and nurses going abroad for better-paying jobs.[70]

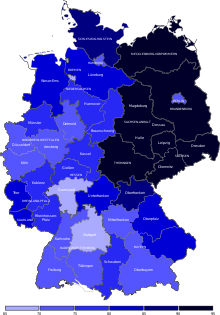

Demographics

[edit]As of 2014, about 16.3 million people with an immigrant background were living in Germany, accounting for every fifth person.[71] Of those 16.3 million, 8.2 million had no German citizenship, more than ever before. Most of them had Turkish, Eastern European or Southern European background. The majority of new foreigners coming to Germany in 2014 were from new EU member states such as Poland, Romania, Bulgaria and Croatia, non-EU European countries like Albania, North Macedonia, Switzerland and Norway or from the Middle East, Africa, East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, South America, North America, Australia and New Zealand. Due to ongoing conflicts in the Middle East, many people are hoping to seek asylum in the European Union and Germany.[72] The vast majority of immigrants are residing in the so-called old states of Germany.[73][74]

In 2022, there were 23.8 million people, 28.7 percent of the total population, who had a migration background.[75]

Immigration regulations

[edit]EU citizens

[edit]European Union free movement of workers principles require that all EU member state citizens have the right to solicit and obtain work in Germany regardless of citizenship. These basic rules for freedom of movement are given in Article 39 of the Treaty on the European Union.

Immigration options for non-EU citizens

[edit]Immigration to Germany as a non-EU-citizen is limited to skilled or highly educated workers and their immediate family members.[76] In April 2012, European Blue Card legislation was implemented in Germany, allowing highly skilled non-EU citizens easier access to work and live in Germany. Although uptake of the scheme has grown steadily since then, its use remains modest; around 27,000 blue cards were issued in Germany in 2018.[77]

Self-employment requires either an initial investment of EUR 250,000 and the creation of a minimum of 5 jobs.[78]

2019 Skilled Immigration Act

[edit]New regulations were enacted in 2020 in response to the 2019 Skilled Immigration Act.[79] In order to qualify for a visa under the new rules, applicants must obtain official recognition of their professional qualification from a certification authority recognized by the German government.[79] Further, the applicant must meet language competency requirements and obtain a declaration from their prospective employer.[79]

Student visa

[edit]International students make up nearly 15 percent of Germany's student population, with 325,000 international students studying in Germany during the winter semester 2020/2021.[80] According to a study from the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF), around 54 percent of foreign students in Germany decide to stay after graduation.[81]

2023 immigration reforms

[edit]Substantial reforms began to be enacted in 2023, touching many aspects of German immigration policy. The Skilled Workers Immigration Act updates previous immigration legislation concerning the ability of foreign workers to find work in Germany or begin employment at a German company.[12] The legislation enables those with substantial professional experience or training to acquire a work permit[12][13] and makes it easier for those with vocational experience or with a university degree to obtain residence permits.[82]

The new law relaxes requirements for obtaining an EU Blue Card. Blue Cards enable highly skilled applicants to stay in an EU country,[83] and the 2023 reforms lowered minimum annual wage requirements[13][84] and guaranteed greater mobility within the EU[12][13] in order to encourage more applicants to use the system. Further, family reunification services are expedited for Blue Card holders, effectively easing immigration for families of Blue Card applicants.[13]

The new legislation also introduces a so-called chance card, which gives applicants without a job offer but with enough qualifications the opportunity to live and work in Germany.[12] Successful applicants are allowed to seek employment for up to a year, with the potential to extend the chance card by two years based on employment.[12][82] Chance card holders must have a university degree or professional training, and must also demonstrate some German proficiency or advanced English skills.[12][82]

Further, the reforms dropped the longstanding restrictions on dual citizenship, allowing most German citizens to hold multiple passports.[85][86] This change brings German citizenship policy in line with the rest of the world which is increasingly shifting towards an acceptance of multiple citizenship.[87] In addition to this change, legal residents only have to wait five years before qualifying for naturalization, as opposed to the previous eight.[85][88]

Context and response to 2023 reforms

[edit]The traffic light coalition that was created after the 2021 federal elections committed to implementing immigration reforms in an effort to make Germany a more competitive labor market.[89] The government argues that Germany, facing a shortage of skilled workers,[89] must attract new talent by facilitating immigration for work[89] and by upending citizenship uptake laws that were among the world's most restrictive.[90]

The government's actions were a response to long standing demands from progressives to modernize German immigration policy[90] and from industry leaders to combat a shortage of skilled labor.[89] By making it easier for job applicants to work in Germany, the government hopes to support a stable supply of skilled professionals that ensure German economic growth and competitiveness[12][91] In July 2024, German Economy Minister Robert Habeck suggested the tax relief for skilled foreign workers.[92]

However, the citizenship reforms incited vigorous debate, causing a scandal involving the anti-immigrant far-right Alternative for Germany[90] (in German, Alternative für Deutschland, AfD). The government argues that the reforms create opportunity and provide security for the 14% of the population that do not have citizenship,[86] aligning German policy with that of Western peers like Canada and France.[86] Opposition leaders argue that the changes devalue German citizenship[86] and introduce the potential for introducing domestically political conflict from abroad.[86][90]

The AfD's political rise in Germany is credited to the political saliency of immigration.[93] The party strongly opposes the citizenship reforms.[90] In 2024, party members were caught meeting with neo-Nazis and other right-wing extremists to discuss the forcible "remigration"[94] of German citizens they deemed insufficiently assimilated.[90][94] News of the meeting triggered massive public backlash as tens of thousands of Germans gathered in major cities like Stuttgart, Berlin and Munich to protest the plan.[95] The AfD distanced itself from the event and insisted that it was not sponsored by the party.[95]

Agreement with Kenya

[edit]A deal signed by both countries in September 2024 opened German labour market for up to a quarter of a million skilled and semi skilled workers from Kenya. It also included an agreement on readmission and return of unwanted individuals. The arrangement came in the face of AfD approaching victory in the next elections.[96]

Asylum seekers and refugees

[edit]German asylum law is based on the 1993 amendment of article 16a of the Basic Law as well as on the 1951 Convention and 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees.

In accordance with the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, Germany grants refugee status to persons that are facing prosecution because of their race, religion, nationality or belonging to a special group. Since 2005, recognized refugees enjoy the same rights as people who were granted asylum.[97] Germany's national ban on deportation doesn't permit returning refugees to their home country should doing so place them in imminent danger or that doing so would break EU human rights laws. This policy is a major catalyst to the large influx of Syrian refugees following the outbreak of the Syrian Civil War.[98]

The distribution of refugees among the federal states is calculated using the "Königsteiner Schlüssel", which is recalculated annually.[99]

Germany hosts one of the largest populations of Turkish people outside Turkey. Kurds make up 80 to 90 percent of all Turkish refugees in Germany while the rest of the refugees are former Turkish military officers, teachers, and other types of public servants who fled the authoritarian government following the coup attempt in July 2016.[100][101][102][103][104][105][106] Among Iraqi refugees in Germany, about 50 percent are Kurds.[107] There are approximately 1.2 million Kurds in Germany.[108]

An institute of forensic medicine in Münster determined the age of 594 of unaccompanied minors in 2019 and found that 234 (40%) were likely 18 years or older and would therefore be processed as adults by authorities. The sample was predominantly males from Afghanistan and Guinea.[109]

In 2015, responding to relatively high numbers of unsuccessful asylum applications from several Balkan countries (Serbia, Albania, Kosovo and Montenegro), the German government formally declared these countries "generally safe" to speed up their processing.[110]

Naturalization

[edit]A person who has immigrated to Germany may choose to become a German citizen. The standard pathway to citizenship is known as Anspruchseinbürgerung (roughly, naturalization by entitlement). In this process, when the applicant fulfills certain criteria they are entitled to become German citizens; the decision is not generally subject to the judgment of a government official. The applicant must:[111]: 19

- be a permanent resident of Germany

- have lived in Germany legally for at least five years, or three years if they have contributed special achievements to Germany

- not live on welfare as the main source of income unless unable to work (for example, if the applicant is a single mother)

- be able to speak German at a 'B1' level in the CEFR standard

- pass a citizenship test. The examination tests a person's knowledge of the German constitution, the Rule of Law and the basic democratic concepts behind modern German society. It also includes a section on the constitution of the Federal State in which the applicant resides. The citizenship test is obligatory unless the applicant can claim an exemption such as illness, disability, or old age.

- not have been convicted of a serious criminal offense

- be prepared to swear an oath of loyalty to democracy and the German constitution

A person who does not fulfill all of these criteria may still apply for German citizenship by discretionary naturalisation (Ermessenseinbürgerung) as long as certain minimum requirements are met.[111]: 38

Spouses and same-sex civil partners of German citizens can be naturalised after only 3 years of residence (and two years of marriage).[111]: 42

Under certain conditions children born on German soil after the year 1990 are automatically granted German citizenship and, in most cases, also hold the citizenship of their parent's home country.

Applications for naturalisation made outside Germany are possible under certain circumstances, but are relatively rare.

Immigrant population in Germany by country of birth

[edit]According to the Federal Statistical Office of Germany in 2012, 92% of residents (73.9 million) in Germany had German citizenship,[112] with 80% of the population being Germans (64.7 million) having no immigrant background. Of the 20% (16.3 million) people with immigrant background, 3.0 million (3.7%) had Turkish, 1.5 million (1.9%) Polish, 1.2 million (1.5%) Russian and 0.85 million (0.9%) Italian background.[113]

In 2014, most people without German citizenship were Turkish (1.52 million), followed by Polish (0.67 million), Italian (0.57 million), Romanians (0.36 million) and Greek citizens (0.32 million).[114]

As of 2023[update], the most common groups of resident foreign nationals in Germany were as follows:[115]

| Rank | Nationality | FSO region | Population | % of foreign nationals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 13,383,910 | 100 | ||

| 1 | EU candidate countries[116] | 1,487,110 | 11.1 | |

| 2 | EU candidate countries | 1,164,200 | 8.7 | |

| 3 | Western Asia[117] | 923,805 | 6.9 | |

| 4 | EU states[118] | 883,670 | 6.6 | |

| 5 | EU states | 880,780 | 6.6 | |

| 6 | EU states | 644,960 | 4.6 | |

| 7 | EU states | 436,325 | 3.3 | |

| 8 | EU states | 429,665 | 3.2 | |

| 9 | East and Central Asia[119] | 377,240 | 2.8 | |

| 10 | EU states | 361,270 | 2.7 | |

| 11 | Other Europe[120] | 290,615 | 2.2 | |

| 12 | Western Asia | 284,595 | 2.1 | |

| 13 | Other Europe | 280,850 | 2.1 | |

| 14 | EU candidate countries | 263,065 | 2.0 | |

| 15 | EU candidate countries | 233,775 | 1.7 | |

| 16 | EU states | 214,695 | 1.6 | |

| 17 | South and South East Asia[121] | 210,385 | 1.6 | |

| 18 | EU states | 193,460 | 1.4 | |

| 19 | EU states | 185,755 | 1.4 | |

| 20 | EU states | 150,295 | 1.1 | |

| 21 | East and Central Asia | 149,550 | 1.1 | |

| 22 | EU candidate countries | 146,380 | 1.1 | |

| 23 | Western Asia | 143,555 | 1.1 | |

| 24 | EU states | 140,320 | 1.0 | |

| 25 | EU states | 139,435 | 1.0 | |

| 26 | North America[122] | 121,420 | 0.9 | |

| 27 | South and South East Asia | 120,535 | 0.9 | |

| 28 | EU candidate countries | 108,555 | 0.8 | |

| 29 | North Africa[123] | 95,095 | 0.7 | |

| 30 | Other Europe | 84,605 | 0.6 | |

| 31 | South and South East Asia | 84,250 | 0.6 | |

| 32 | West Africa | 83,470 | 0.6 | |

| 33 | East Africa[124] | 81,955 | 0.6 | |

| 34 | EU states | 64,290 | 0.5 | |

| 35 | EU states | 64,235 | 0.5 | |

| 36 | South and South East Asia | 59,880 | 0.4 | |

| 37 | EU states | 58,360 | 0.4 | |

| 38 | South America[125] | 55,710 | 0.4 | |

| 39 | East Africa | 55,470 | 0.4 | |

| 40 | East and Central Asia | 48,655 | 0.4 | |

| 41 | North Africa | 48,295 | 0.4 | |

| 42 | North Africa | 47,430 | 0.4 | |

| 43 | West Africa | 45,555 | 0.3 | |

| 44 | Western Asia | 45,525 | 0.3 | |

| 45 | EU candidate countries | 45,345 | 0.3 | |

| 46 | EU candidate countries | 44,390 | 0.3 | |

| 47 | EEA/Switzerland[126] | 41,325 | 0.3 | |

| 48 | EU states | 41,240 | 0.3 | |

| 49 | East and Central Asia | 38,545 | 0.3 | |

| 50 | East and Central Asia | 37,180 | 0.3 | |

| Other nationalities | 1,146,830 | 8.6 |

Comparison with other European Union countries 2023

[edit]According to Eurostat 59.9 million people lived in the European Union in 2023 who were born outside their resident country. This corresponds to 13.35% of the total EU population. Of these, 31.4 million (9.44%) were born outside the EU and 17.5 million (3.91%) were born in another EU member state.[127][128]

| Country | Total population (1000) | Total foreign-born (1000) | % | Born in other EU state (1000) | % | Born in a non EU state (1000) | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EU 27 | 448,754 | 59,902 | 13.3 | 17,538 | 3.9 | 31,368 | 6.3 |

| Germany | 84,359 | 16,476 | 19.5 | 6,274 | 7.4 | 10,202 | 12.1 |

| France | 68,173 | 8,942 | 13.1 | 1,989 | 2.9 | 6,953 | 10.2 |

| Spain | 48,085 | 8,204 | 17.1 | 1,580 | 3.3 | 6,624 | 13.8 |

| Italy | 58,997 | 6,417 | 10.9 | 1,563 | 2.6 | 4,854 | 8.2 |

| Netherlands | 17,811 | 2,777 | 15.6 | 748 | 4.2 | 2,029 | 11.4 |

| Greece | 10,414 | 1,173 | 11.3 | 235 | 2.2 | 938 | 9.0 |

| Sweden | 10,522 | 2,144 | 20.4 | 548 | 5.2 | 1,596 | 15.2 |

| Austria | 9,105 | 1,963 | 21.6 | 863 | 9.5 | 1,100 | 12.1 |

| Belgium | 11,743 | 2,247 | 19.1 | 938 | 8.0 | 1,309 | 11.1 |

| Portugal | 10,467 | 1,684 | 16.1 | 378 | 3.6 | 1,306 | 12.5 |

| Denmark | 5,933 | 804 | 13.6 | 263 | 4.4 | 541 | 9.1 |

| Finland | 5,564 | 461 | 8.3 | 131 | 2.4 | 330 | 5.9 |

| Poland | 36,754 | 933 | 2.5 | 231 | 0.6 | 702 | 1.9 |

| Czech Republic | 10,828 | 764 | 7.1 | 139 | 1.3 | 625 | 5.8 |

| Hungary | 9,600 | 644 | 6.7 | 342 | 3.6 | 302 | 3.1 |

| Romania | 19,055 | 530 | 2.8 | 202 | 1.1 | 328 | 1.7 |

| Slovakia | 5,429 | 213 | 3.9 | 156 | 2.9 | 57 | 1.0 |

| Bulgaria | 6,448 | 169 | 2.6 | 58 | 0.9 | 111 | 1.7 |

| Ireland | 5,271 | 1,150 | 21.8 | 348 | 6.6 | 802 | 15.2 |

Crime

[edit]In 2006, in Bavaria, 4% of the foreign population were criminal suspects. The corresponding figure for the non-foreign population was 2%.[130] Non-German citizens are, in general, over-represented among suspects in criminal investigations (see horizontal bar chart).[129] However, the complex nature of the data means it is not straightforward to make observations about the crime rates among immigrants. One factor is that crimes committed by foreign nationals are twice as likely to be reported as those committed by German citizens.[131] In addition, the clearance rate (the percentage of crimes that are solved successfully) is extremely low in some categories, such as pickpocketing (5% solved) and burglaries (17% solved). When considering solved crimes only, non-German nationals make up around 8% of all suspects.[132]

A disproportionate number of organized crime families in Germany are run by immigrants or their children. One-fifth of investigations into organized crime involve one or more non-German suspects.[132] This has been attributed to the lack of effort made to integrate newly arrived immigrants in the 1960s and 1970s, who at the time were seen as "temporary" guest workers.[133]

Poverty

[edit]Working-class immigrant families—particularly those with multiple children—experience poverty rates higher than the national average.[134] Minorities are the most likely to rely on welfare as the main source of income.[135]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "International Migration Database". stats.oecd.org. OECD. Archived from the original on 6 July 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ^ Bildung, Bundeszentrale für politische. "Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund I | bpb". bpb.de (in German). Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Migrations in the German lands, 1500-2000. Jason Philip Coy, Jared Poley, Alexander Schunka (1st ed.). New York. 2016. ISBN 978-1-78533-144-2. OCLC 934603332. Archived from the original on 24 February 2024. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Germany Top Migration Land After U.S. in New OECD Ranking". Migration Policy Institute. 2019. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ "Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund um 8,5 % gestiegen". Archived from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ "Right and wrong ways to spread languages around the globe". The Economist. 31 March 2018. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "Fünf Jahre Arbeitnehmerfreizügigkeit in Deutschland | bpb". bpb.de (in German). Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. 28 April 2016. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ Jones, P.N.; Wild, M.T. (February 1992). "Western Germany's 'third wave' of migrants: the arrival of the Aussiedler". Geoforum. 23 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/0016-7185(92)90032-Y. PMID 12285947. Archived from the original on 24 February 2024. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "Germany Population 2018", World Population Review, archived from the original on 30 August 2023, retrieved 15 July 2018

- ^ a b Oltmer, Vera Hanewinkel, Jochen (20 September 2017). "Grundzüge der deutschen (Arbeits-)Migrationspolitik - Migrationsprofil Deutschland". bpb.de (in German). Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Moving to Germany will be easier in 2024 under a new visa scheme". www.euronews.com. 16 October 2023. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Germany: New "Skilled Workers Immigration Act" Enacted". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Germany's progressive immigration reform". parakar.eu. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Germany reforms citizenship law – DW – 01/19/2024". dw.com. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ SpiegelOnline Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, 25 January 2011.

- ^ "Konrad Adenauer Stiftung" Archived 16 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine, viewed on 31 March 2015.

- ^ "Gastarbeiter". Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (in German). Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ "Erstes "Gastarbeiter-Abkommen" vor 55 Jahren | bpb". Bundeszentrum für politische Bildung (in German). 17 December 2020. Archived from the original on 6 November 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ Luft, Stefan (5 August 2014). "Die Anwerbung türkischer Arbeitnehmer und ihre Folgen | bpb". Bundeszentrum für politische Bildung (in German). Archived from the original on 6 November 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ "Sixty years of Turkish "guest workers" in Germany". The Economist. 6 November 2021. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 6 November 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ ""Aus Vietnam in die DDR. 40 Jahre Vertragsarbeiter-Abkommen"". Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung (in German). Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ Forster, Gioia; Krüger, Ralf (4 November 2019). "DDR-Vertragsarbeiter aus Afrika: "Die haben uns belogen und betrogen"". ZDF (in German). Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ Mai, Marina (3 March 2019). "Vertragsarbeiter aus Mosambik: "Moderne Sklaverei" in der DDR". Die Tageszeitung (in German). ISSN 0931-9085. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ "Kuba und die DDR | MDR.DE". Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk (in German). Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ a b Rabenschlag, Ann-Judith (15 September 2016). "Arbeiten im Bruderland. Arbeitsmigranten in der DDR und ihr Zusammenleben mit der deutschen Bevölkerung | bpb". Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (in German). Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ Mai, Marina (3 March 2019). "Vertragsarbeiter aus Mosambik: "Moderne Sklaverei" in der DDR". Die Tageszeitung: taz (in German). ISSN 0931-9085. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ Karin Weiss: "Die Einbindung ehemaliger vietnamesischer Vertragsarbeiterinnen und Vertragsarbeiter in Strukturen der Selbstorganisation", In: Almut Zwengel: "Die Gastarbeiter der DDR - politischer Kontext und Lebenswelt". Studien zur DDR Gesellschaft; p. 264

- ^ Pfohl, Manuela (1 October 2008), "Vietnamesen in Deutschland: Phuongs Traum", Stern, retrieved 18 October 2008

- ^ a b c d Eric Solsten (1995). "Germany: A Country Study; Chapter: Immigration". Washington DC: GPO for the Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ Darnstädt, Thomas (6 November 1988). "Deutsches Blut, fremde Folter SPIEGEL-Redakteur Thomas Darnstädt". Der Spiegel (in German). ISSN 2195-1349. Archived from the original on 1 November 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ Seifert, Wolfgang. "Geschichte der Zuwanderung nach Deutschland nach 1950 | bpb". bpb.de (in German). Archived from the original on 1 November 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ Migration Policy Institute (1 July 2004). "Germany: Immigration in Transition". Migration Policy Institute. Archived from the original on 26 January 2024. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Phalnikar, Sonia (7 September 2007). "Russia Hopes to Lure Back Ethnic Germans | DW | 07.09.2007". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 26 June 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "Die Spreu vom Weizen trennen". Der Spiegel (in German). 21 September 1986. ISSN 2195-1349. Archived from the original on 1 November 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ Schührer, Susanne (2018). "Türkeistämmige Personen in Deutschland" (PDF). Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge: Forschungszentrum Migration, Integration und Asyl. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 November 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ "Flüchtlingskrise: "Viele waren schon in der Heimat Underdogs"". Die Welt (in German). 5 January 2016. Archived from the original on 19 November 2020. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ " Kriegsflüchtlinge aus dem ehemaligen Jugoslawien nach Zielland (Schätzung des UNHCR, Stand März 1995)" Archived 14 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, viewed on 31 March 2015.

- ^ a b Kay Hailbronner (1994). "Asylum law reform in the German Constitution" (PDF). American University International Law Review. pp. 159–179. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ^ James M. Didden (1994). "Toward collective responsibility in asylum law: Reviving the eroding right to political asylum in the US and the Federal Republic of Germany" (PDF). American University International Law Review. pp. 79–123. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF): Asylum law Archived 21 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Asylbewerberleistungen" Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, published on 4 September 2014.

- ^ "Mehr als 10 Millionen Ausländer in Deutschland". Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ "Eurostat table [migr_eipre] Third country nationals found to be illegally present - annual data (rounded)". Eurostat. 17 July 2017. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ Integration, Mediendienst. "Zahl der Flüchtlinge | Flucht & Asyl | Zahlen und Fakten | MDI". Mediendienst Integration (in German). Archived from the original on 22 June 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Hanewinkel, Vera (15 December 2015). "Fluchtmigration nach Deutschland und Europa: Einige Hintergründe". bpb.de (in German). Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ "Zahl der Flüchtlinge erreicht "Allzeithoch"" Archived 1 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 19 August 2015

- ^ "Neue Prognose für Deutschland 2015: Vizekanzler Gabriel spricht von einer Million Flüchtlingen" Archived 16 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ^ a b c Schönhagen, Ulrich Herbert, Jakob (17 July 2020). "Vor dem 5. September. Die "Flüchtlingskrise" 2015 im historischen Kontext | APuZ". bpb.de (in German). Archived from the original on 19 June 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Who bears the cost of integrating refugees?" (PDF). OECD Migration Policy Debates. 13 January 2017: 2. 9 January 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 November 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ "Irregular Migrant, Refugee Arrivals in Europe Top One Million in 2015: IOM". IOM. 22 December 2015. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ "Migrant crisis: People treated 'like animals' in Hungary camp". BBC News. 11 September 2015. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Becher, Lena (9 July 2019). "Die Beschäftigung von Flüchtlingen wächst – die Arbeitslosigkeit auch". O-Ton Arbeitsmarkt. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Dernbach, Andrea (23 January 2020). "Wie das Integrationsgesetz die Integration behindert". www.tagesspiegel.de (in German). Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Graf, Johannes. "Migration Monitoring: Educational and Labour Migration to Germany" (PDF). bamf.de. Federal Office for Migration and Refugees. p. 39. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ^ Clashes at migrant hostel stir German integration fears Archived 17 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine Reuters, 3 May 2018

- ^ Karnitschnig, Matthew (31 August 2020). "5 years on from Angela Merkel's three little words: 'Wir schaffen das!'". POLITICO. Archived from the original on 1 November 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ Hindy, Lily (6 September 2018). "Germany's Syrian Refugee Integration Experiment". tcf.org. The Century Foundation. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Quadbeck, Eva (9 June 2016). "Übergriffe von Köln: Silvester-Täter kamen mit Flüchtlingswelle ins Land". Rheinische Post (in German). Archived from the original on 1 November 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ Mitchell, Travis (29 November 2017). "The Growth of Germany's Muslim Population". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. Archived from the original on 25 November 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ "Current Figures on Asylum". Archived from the original on 13 June 2016.

- ^ "Germany: Asylum applications rose sharply in 2023". Deutsche Welle. 9 January 2024.

- ^ "What's behind the surge in migrant arrivals to Italy?". AP News. 15 September 2023. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- ^ "Germany agrees to accept some migrants from Italy amid Lampedusa crisis". Telewizja Polska. 16 September 2023.

- ^ DW, Reuters. "Ukrainian refugees push Germany's population to record high". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Maria Martinez (19 January 2023), Migration drives German population to record high in 2022 Archived 26 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine Reuters.

- ^ "Germany: Net immigration sinks sharply in 2023". Deutsche Welle. 27 June 2024.

- ^ "Germany opens its doors to Kenyan workers in controlled migration deal". CNN. 14 September 2024.

- ^ "How is Germany handling its migration partnerships?". Deutsche Welle. 2 September 2024.

- ^ "Germany begins recruiting 250,000 bus drivers, computer repairers from Kenya". Peoples Gazette. 13 September 2024.

- ^ "Germany to welcome Kenyans in labour deal". BBC. 14 September 2024.

- ^ "Pegida - Faktencheck: Asylbewerber". Frankfurter Rundschau. Archived from the original on 26 December 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ Knapp 8,2 Millionen Ausländer leben in Deutschland Archived 19 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine, "sueddeutsche.de" published in March 2015 .

- ^ "Ausländische Bevölkerung nach Ländern" Archived 29 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Conflicts in the Middle East fueled by religious intolerance" Archived 8 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ "Pressemitteilung Nr. 158 vom 20. April 2023". Statistisches Bundesamt. 20 April 2023. Archived from the original on 7 November 2023.

- ^ "Ordinance on employment (German)". Archived from the original on 6 February 2009. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- ^ "Figures on the EU Blue Card". BAMF - Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ Residence Act in the version promulgated on 25 February 2008 Archived 15 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine (Federal Law Gazette I p. 162), last amended by Article 3 of the Act of 6 September 2013 (Federal Law Gazette I p. 3556)

- ^ a b c "Skilled Immigration Act (Fachkräfte-Einwanderungsgesetz)". German Missions in India. 6 March 2020. Archived from the original on 16 June 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ DAAD. "Wissenschaft weltoffen kompakt 2022" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ "BAMF's Graduates Study: Every second foreign student stays in Germany after graduation". Make it in Germany. German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy. 20 February 2015. Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ a b c "Changes to Germany's skilled immigration rules take effect – DW – 03/01/2024". dw.com. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Essential information - European Commission". immigration-portal.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "The Skilled Immigration Act". www.make-it-in-germany.com. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Germany reforms citizenship law – DW – 01/19/2024". dw.com. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "German parliament approves easing rules to get citizenship, dropping restrictions on dual passports". AP News. 19 January 2024. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "16 Countries That Allow Multiple Citizenship in the World". Yahoo Finance. 27 February 2024. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Germany: New Citizenship Law to Enter into Force in June 2024". Fragomen - Immigration attorneys, solicitors, and consultants worldwide - Germany: New Citizenship Law to Enter into Force in June 2024. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Moving to Germany will be easier in 2024 under a new visa scheme". www.euronews.com. 16 October 2023. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "Germany's parliament approves easing citizenship laws". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Germany calls for more immigrants to fix its shrinking economy". Financial Times. 11 October 2023.

- ^ "Germany's proposed tax rebate for skilled foreign workers 'socially explosive'". Euronews. 9 July 2024.

- ^ Zhou, Li (12 March 2024). "The dangerous resurgence of Germany's far right, explained". Vox. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ a b Mannheim, Linda (23 January 2024). "The AfD's Secret Plan to Deport Millions From Germany". ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ a b Tanno, Sophie (20 January 2024). "Germany's far-right AfD face mounting protests over plan to deport migrants". CNN. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "German opens door for thousands of Kenyan workers in labour deal". BBC. 14 September 2024. Retrieved 14 September 2024.

- ^ Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF): Protecting refugees Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "National ban on deportation". www.bamf.de. BAMF. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ^ "Gemeinsame Wissenschaftskonferenz – Büro – Bekanntmachung des Königsteiner Schlüssels für das Jahr 2014". 4 January 2015. Archived from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ Jansen, Frank (23 August 2016). "Auffallend viele kurdische Flüchtlinge". Der Tagesspiegel Online. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ "BMI Bundesinnenminister Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble: Asylbewerberzugang im Jahr 2005 auf niedrigsten Stand seit 20 Jahren". Archived from the original on 26 June 2008. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ^ "Asylanträge von Türken in BW: "Fast 90 Prozent sind Kurden" - Baden-Württemberg - Nachrichten". Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ Politik (25 December 2016). "Zahl der türkischen Asylbewerber verdreifacht". Spiegel.de. Archived from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^ "Nach Putschversuch: Immer mehr Türken beantragen Asyl in Deutschland". Welt.de. 25 December 2016. Archived from the original on 7 May 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^ Reuters Editorial. "Turkish asylum applications in Germany jump 55 percent this year". U.S. Archived from the original on 12 September 2018. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Report: At least 1,400 Turkish nationals claimed asylum in Germany in Jan-Feb alone - Turkey Purge". Turkey Purge. 2 April 2018. Archived from the original on 12 September 2018. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ^ "BMI Bundesinnenminister Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble: Asylbewerberzugang im Jahr 2005 auf niedrigsten Stand seit 20 Jahren". Archived from the original on 26 June 2008. Retrieved 26 June 2008.

- ^ "Kurds in Germany stress on own identity in... | Rudaw.net". Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^ "Zweifel an Minderjährigkeit: 40 Prozent der überprüften Flüchtlinge gaben Alter falsch an". FOCUS Online (in German). Archived from the original on 21 September 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ "Berlin plant Sammelunterkunft für Balkan-Flüchtlinge". Die Zeit (in German). 28 December 2015. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ a b c Federal Government Commissioner for Migrants, Refugees and Integration. Wege zur Einbürgerung. Wie werde ich Deutsche? – Wie werde ich Deutscher? Archived 11 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine 2008.

- ^ Federal Statistical Office of Germany (Destatis).sicker and golden family Population based on the 2011 Census. Population by sex and citizenship Archived 28 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF). Migrationsbericht des Bundesamtes für Migration und Flüchtlinge im Auftrag der Bundesregierung. Migrationsbericht 2012 Archived 25 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. 2014.

- ^ Federal Statistical Office of Germany (Destatis). Foreign population, 2007 to 2013 by selected citizenships Archived 2 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Statistischer Bericht - Ausländische Bevölkerung 2022". Archived from the original on 6 April 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2023.

- ^ German: EU-Kandidatenländer

- ^ German: Vorderasien

- ^ German: EU-Staaten

- ^ German: Ost- und Zentralasien

- ^ German: Sonstiges Europa

- ^ German: Süd- und Südostasien

- ^ German: Nordamerika

- ^ German: Nordafrika

- ^ German: Ostafrika

- ^ German: Südamerika

- ^ German: EWR-Staaten/Schweiz

- ^ "Population on 1 January by age group, sex and country of birth". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ "Population on 1 January by age, sex and group of country of birth". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ a b Pancevski, Bojan (15 October 2018). "An Ice-Cream Truck Slaying, Party Drugs and Real-Estate Kings: Ethnic Clans Clash in Berlin's Underworld". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ Walburg, Christian (25 September 2020). "Migration und Kriminalität – Erfahrungen und neuere Entwicklungen | bpb". bpb.de (in German). Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Knight, Ben (3 January 2018). "Study: Only better integration will reduce migrant crime rate". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ a b Kriminalität im Kontext von Zuwanderung: Bundeslagebild 2019. Bundeskriminalamt. 2019. pp. 54, 60. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Ghadban, Ralph (28 September 2018). "Die Macht der Clans". sueddeutsche.de (in German). ISSN 0174-4917. Archived from the original on 29 September 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ^ Olaf Groh-Samberg: Armut verfestigt sich Wochenbericht der DIW Nr. 12/2007, 74. Jahrgang/21. März 2007

- ^ (in German) Focus, 1 December 2008, "Alleinerziehende: 43 Prozent bekommen Hartz IV"

Further reading

[edit]- Czymara, Christian S., and Alexander W. Schmidt-Catran. "Refugees unwelcome? Changes in the public acceptance of immigrants and refugees in Germany in the course of Europe's ‘immigration crisis’." European Sociological Review 33.6 (2017): 735-751. online

- Ellermann, Antje. The Comparative Politics of Immigration: Policy Choices in Germany, Canada, Switzerland, and the United States (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

- Green, Simon. "Germany: A changing country of immigration." German Politics 22.3 (2013): 333–351. online

- Hertner, Isabelle. "Germany as ‘a country of integration’? The CDU/CSU's policies and discourses on immigration during Angela Merkel's Chancellorship." Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies (2021): 1-21.

- Joppke, Christian. Immigration and the nation-state: the United States, Germany, and Great Britain (Clarendon Press, 1999), compartative responses.

- Kurthen, Hermann. "Germany at the crossroads: national identity and the challenges of immigration." International Migration Review 29.4 (1995): 914–938. online

- Mushaben, Joyce Marie. "A Spectre Haunting Europe: Angela Merkel and the Challenges of Far-Right Populism." German Politics and Society 38.1 (2020): 7-29.

- Piatkowska, Sylwia J., Andreas Hövermann, and Tse-Chuan Yang. "Immigration Influx as a Trigger for Right-Wing Crime: A Temporal Analysis of Hate Crimes in Germany in the Light of the ‘Refugee Crisis’." The British Journal of Criminology 60.3 (2020): 620-641.

- Schmidt-Catran, Alexander W., and Dennis C. Spies. "Immigration and welfare support in Germany." American Sociological Review 81.2 (2016): 242–261. online

- Thrädhardt, Dietrich. "Germany's immigration policies and politics." in Mechanisms of Immigration control: a comparative analysis of European regulation policies (Routledge, 2020) pp. 29–57.

- Vierra, Sarah Thomsen. Turkish Germans in the Federal Republic of Germany: Immigration, Space, and Belonging, 1961–1990 (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

External links

[edit]- "6.180,013" Ausländer in Deutschland

- "Unsere Aufnahmekapazität ist begrenzt, ..."

- German Foreign Office

- Facts & Figures in English Mediendienst Integration

- Federal Office for Migration and Refugees

- Make it in Germany The Federal Government