Ahmad Sirhindi

Shaykh Ahmad al-Faruqi al-Sirhindi

| |

|---|---|

Painting of Shaykh Ahmad Al-Sirhindi c. 16th-17th Century | |

| Title | Mujadid-i-Alf-i-Thani (Reviver of the Second Millennium). |

| Personal life | |

| Born | 26 May[1][2] 1564[3]: 90 /1563[4] |

| Died | 10 December 1624 (aged 60) Sirhind, Lahore Subah, Mughal Empire |

| Era | Mughal India |

| Main interest(s) | Islamic Law, Islamic philosophy |

| Notable idea(s) | Evolution of Islamic philosophy Application of Islamic law |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Islam |

| Denomination | Sunni |

| Jurisprudence | Hanafi |

| Tariqa | Naqshbandi |

| Creed | Maturidi[5] |

| Muslim leader | |

Influenced by | |

Influenced | |

Ahmad Sirhindi[a] (1564 – 1624/1625)[8] was an Indian Islamic scholar, Hanafi jurist, and member of the Naqshbandī Sufi order who lived during the era of Mughal Empire.[9][10]

Ahmad Sirhindi opposed heterodox movements within the Mughal court such as Din-i Ilahi, in support of more orthodox forms of Islamic Law.[11][12] His act of preserving and urging the practice of Islamic orthodoxy has cemented his reputation by some followers as a Mujaddid, or a "reviver".[13][14][15]

While early and modern South Asian scholarship credited him for contributing to conservative trends in Indian Islam, more recent works, such as Abul Hasan Ali Hasani Nadwi[16] and commentaries from western scholars such as Ter Haar, Friedman, and Buehler, have pointed to Sirhindi's significant contributions to Sufi epistemology and practices.[17][18][19][20]

Biography

[edit]Sirhindi was born on 26 May 1564 in the village of Sirhind, Punjab to a Punjabi Muslim family.[21][3]: 90 A descendant of 13th-century Sufi saint and poet Baba Farid, he claimed ancestry from the second Rashidun caliph, Umar (634–644).[22][23][24] Sirhindi received most of his early education from his father, 'Abd al-Ahad, his brother, Muhammad Sadiq and from a Lahore-based scholar Muhammad Tahir al-Lahuri.[25] He also memorised the Qur'an. He then studied in Sialkot, which had become an intellectual centre under the scholar Kamaluddin Kashmiri.[3]: 90 [26] Qazi Bahlol Badakhshani taught him jurisprudence, Muhammad's biography and history.[27][28] He eventually joined the Naqshbandī order through the Sufi missionary Khwaja Baqi Billah when he was 36 years old,[29] and became a leading master of the order. His deputies traversed the Mughal Empire in order to popularize the order and eventually won favour with the Mughal court.[30] Sirhindi underwent his first Hajj pilgrimage in 1598, after the death of his father.[4]

During the reign of emperor Akbar, Ahmad Sirhindi wrote hundreds of letters which were aimed towards his disciples, Mughal nobles, and even the emperor himself, to denounce the participations of Hindu figures in the government.[31] Annemarie Schimmel recorded about 534 letters has been wrote by Ahmad Sirhindi regarding the subject of Syncretism.[15] His efforts influenced Abul Fazl, protegee of emperor Akbar, to support Ahmad Sirhindi in an effort to convince Jahangir, successor of Akbar, to reverse the policies of Akbar of tolerating Hindus in Mughal court.[31] According to the modern Syrian salafi jurist Ali al-Tantawi, Ahmad Sirhindi never aspired to depose the emperor despite his fierce criticism; instead, he wanted to reform the religious policies of the late emperor so he sent letters inflamed with religious fervor and faith towards young commanders and courtiers and to gather them into his cause to reverse the emperor's religious policy to persuade the emperor.[32]

Later, during the reign of emperor Jahangir, Ahmad Sirhindi continued his religious discourses by writing a large number of letters to the nobles, particularly towards Shaikh Farid Murtaza Khan, a Mir Bakshi official, to convince the emperor about this religious issue.[10] It is also known through his letter correspondence with the imperial government figures that Ahmad Sirhindi routinely attended the court debates to counteract some religious beliefs and doctrines which were prevalent in the court.[33] In the process, it is recorded from these correspondence which compiled in 1617, that Farid Murtaza Khan took Ahmad Sirhindi advices regarding this matter.[10] Ahmad Sirhindi also wrote a letter to Mughal Emperor Jahangir emphasizing that he is now correcting the wrong path taken by his father, emperor Akbar.[34]

At some point during the reign of Jahangir, Ahmad Sirhimdi sent many pupils for academic missionaries into various places, such as:[35]

- 70 individuals which led by his pupil named Muhammad Qasim to Turkestan.

- 40 individuals under another pupil named Faruh Hussain into Arabian Peninsula, Yemen, Syria, and Anatolia.

- 10 individuals under another pupil named Muhammad Sadiq into Kashgar.

- 30 individuals under another pupil named Shaykh Ahmad Bakri into the outskirt of Turkestan, Badakhshan, and Khurasan.

Later, Ahmad Sirhindi was imprisoned by the emperor.[36] This happened in 1618,[4] Emperor Jahangir, who distanced himself from the Islam orthodoxy and admired Vaishnavite ascetic, Chitrarup.[37] But later the emperor rectified his order and freed Ahmad Sirhindi.[38] However, Ahmad Sirhindi was imprisoned once again in 1622, suggested to be due to the jealousy of several nobles for his popularity, before being released again after spending one year in Gwalior prison and another three years in a prison within emperor Jahangir army entourage.[4][15]

After his release and restoration of favor and honor, Ahmad Sirhindi accompanied emperor Jahangir in his entourage into Deccan Plateau.[31] Modern Indian historian Irfan Habib considers the efforts of Ahmad Sirhindi to bear success as emperor Jahangir started changing the policies which were criticized by Ahmad Sirhindi.[10] Ahmad Sirhindi likely stayed to accompany the emperor for three years before his death.[10] He continued to exercise influence over the Mughal court along with his son, Shaikh Masoom, who tutored the young prince Aurangzeb.[10] Ahmad Sirhindi died in the morning of 10 December 1624.[4]

Another son of Ahmad Sirhindi, Khwaja Muhammad Masoom, supported Aurangzeb during the Mughal succession conflict, by sending his two sons, Muhammad Al-Ashraf, and Khwaja Saifuddin, to support Aurangzeb in war.[39] Aurangzeb himself provided Khwaja Muhammad and his youngest son, Muhammad Ubaidullah, with fifteen ships to seek refugee during the conflict to embark for Hajj pilgrimage, and Khwaja Muhammad returned to India after Aurangzeb won the conflict two years later.[39]

Personal view

[edit]Abul Hasan Ali Hasani Nadwi, Islamic scholar, thinker, writer, preacher, reformer and a Muslim public intellectual of 20th century India, wrote the biography of Ahmad Sirhindi in his book, Rijal al-Fikr wa l-Da'wah fi al-Islam, which covers mostly the thought of Ahmad Sirhindi's efforts in revival of Islam and opposition of heresies.[16] While on another occasion, in a letter to Lãlã Beg (a Subahdar of Bihar[40]), he regards Akbar's prohibition of cow-slaughter as interference in the religious freedom of Muslims.[41] Ahmad Sirhindi were recorded to also defy the old tradition of Sujud or prostrating towards the ruler as he viewed this practice as Bid'ah.[36] Ahmad Sirhindi also repeatedly stated his proud ancestry to Rashidun caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab to show he was similarly in favour of orthodoxy and fierce denunciations of heresies.[24] He criticized the practices such as Raqs, or Sufi whirling.[42][43] While also emphasizing the criticism to any rituals or practices that not included in Sharia.[42]: 200-201

The societal reforms of Mughal empire by Ahmad Sirhindi methodology has several targets which he aimed to convey. He viewed that to reform the society, one must convey his thoughts towards 6 elements of society accordingly, such as:[44]

- Non-governmental influential class

- members of the imperial courts

- King

- Scholars

- Heretics and ignorant Sufis

- Liberal scholars

Meanwhile, Ahmad Sirhindi personally accepted the use of Ijtihad and Qiyas in Islamic Jurisprudence and defended the use of both.[45][46] Ahmad Sirhindi argued that Qiyas and Itjihad were not included on Bidʻah[45]

Regarding the Hindu practice, The puritanical Ahmad Sirhindi condemns the thought from some Hindu thinkers, such as Hardai Ram, that Bhakti movement was identical with the Islamic mysticism.[10][43]

Philosophy

[edit]Ahmad Sirhindi's opposition to emperor Akbar regarding Din-i Ilahi's syncretic belief were recorded in fourth volume of Tarikh-e-Dawat-o-Azeemat.[47] Ahmad Sirhindi also rejected the ideas of philosophy, particularly those rooted from Greek philosophy.[48] Furthermore, Sirhindi criticize the method of interpretating the meaning of Quran with philosophy.[49][46]

Ahmad Sirhindi view regarding some of teachings found in Ibn Arabi's teaching in Waḥdat al-Wujūd.[50] He argued that the doctrine of Ibn Arabi is incompatible with Islam.[51] In his book, Ahmad Sirhindi criticized the doctrine of Waḥdat al-Wujūd,[52] by saying in his book, Al-Muntakhabaat Min Al-Maktubaat, that God is never united with anything, and nothing can be united with God.[42] Ahmad Sirhindi argued that forms of pantheism were components of Hinduism.[53][54][46] He rejected the core idea of ibn Arabi that the creation could unite with the Creator, i.e., God.[55]

Despite this, Sirhindi still used Ibn al-'Arabi's vocabulary without hesitation.[3]: 95 William C. Chittick, an expert of Ibn 'Arabi biography, argued that Ahmad Sirhindi seems oblivious of Ibn 'Arabi doctrines, as the Imam insisted that Wahdat al Wujud were "inadequate expression" which should be supplanted by his concept of Wahdat as-Shuhud which Chittick claimed is just similar in essence.[56] Ahmad Sirhindi advanced the notion of wahdat ash-shuhūd (oneness of appearance).[3]: 93 According to this doctrine, the experience of unity between God and creation is purely subjective and occurs only in the mind of the Sufi who has reached the state of fana' fi Allah (to forget about everything except Almighty Allah).[57] Sirhindi considered wahdat ash-shuhūd to be superior to wahdat al-wujūd (oneness of being),[3]: 92 which he understood to be a preliminary step on the way to the Absolute Truth.[58]

Aside from the doctrine of pantheism of Ibn 'Arabi, Ahmad Sirhindi also expressed his opposition towards the idea of Metempsychosis or the migration of soul from one body to another.[59]

Shia

[edit]Sirhindi also wrote a treatise under the title "Radd-e-Rawafiz" to justify the execution of Shia nobles by Abdullah Khan Uzbek in Mashhad. Ahmad Sirhindi argues that since the Shiite were cursing the first three Rashidun caliphs, Abu Bakr, Umar, and Uthman, and also chastising the Wives of Muhammad, he advocated for the oppression towards Shiite and supported the destruction of their buildings and confiscating their properties.[60] Ahmad Sirhindi also expressed his hate towards Shias in his letters, where according to him, the worst distorters of faith "are those who bear malice against the companions of Prophet Muhammad. God has called them Kafirs in the Quran." In a letter to his discple Sheikh Farid,[61] the Mir Bakhshi of the Mughal Empire, he said that showing respect to the distorters of faith (Ahl-e-Bidʻah) amounted to destruction of Islam.[62] Ahmad Sirhindi believed the Shia, Mahdawi, and the mystics were responsible for the decline of Sunni Muslim unity in India.[63]

Sikh

[edit]Ahmad Sirhindi recorded his hostility towards the Sikhs. In his Makutbat letter 193, he is said to have stated [sic]:[64][65][66][67]

"The execution of the accused Kafir of Goindwal at this time is a very good achievement indeed and has become the cause of a great defeat of hateful Hindus. With whatever intention they are killed and with whatever objective they are destroyed it is a meritorious act for the Muslims. Before this Kafir was killed, I have seen a dream that Emperor of the day had destroyed the crown of the head of Shirk or infidelity. It is true that this infidel was the chief of the infidels and a leader of the Kafirs. The object of levying Jazia on them is to humiliate and insult the Kafirs and Jehad against them and hostility towards them are the necessities of the Muhammedan faith."

— Ahmad Sirhindi, No. 193 in Part III of Vol. I of Muktubat-i-Imam Rubbani Hazrat Mujaddid-i-Alf-i-Sani

As a hard-line supporter of Islamic orthodoxy and a highly influential religious revivalist, Ahmad Sirhindi had opposed Akbar's policy of religious tolerance. He had concerns about the spread of Sikhism in Punjab. So, he cheered on the murder of the Guru, thus giving it a religious rather than political colour.[68][69]

Sufi

[edit]One of the biggest criticism of Ahmad Sirhindi towards the ritual and practice of his contemporary Sufi community was their neglection of Sharia, since he viewed those who followed Sufi Tariqa viewed that Sharia is not enough for pursuing Ma'rifa. Ahmad Sirhindi even goes so far that in his book he branded such kind of Sufi who abandon Sharia as apostates.[70]

Ahmad Sirhindi's teaching emphasized the inter-dependence of both the Sufi path and Sharia, stating that "what is outside the path shown by the prophet is forbidden."[42]: 95-96 In his criticism of the superficial jurists, he states: "For a worm hidden under a rock, the sky is the bottom of the rock."[71] Meanwhile, Muhammad ibn Ahmad Hamid ad-Din al Farghani ad-Dimasyqi al-Hanafi, a Hanafite scholar who lived during 9th AH, recorded in his book, Jihad Ulama al-Hanafiyat fi 'Ibthal 'Aqaa'id al-Quburiyya, that Ahmad Sirhindi were one of Hanafite Imam who opposed the practice of Quburiyyun among Sufist.[72]

According to Simon Digby, "modern hagiographical literature emphasizing Ahmad Sirhindi effort for strict Islamic orthodoxy, Sharia and religious observance."[73] modern scholar Yohanan Friedmann also noted about the commitment of Ahmad Sirhindi in exhotation about Sharia or practical observance Islam remains extreme, despite his huge focus on the discourse about Sufi experience.[73] However, Friedman in his other works claims Ahmad Sirhindi was primarily focusing on towards discourse of Sufism in mysticism instead.[74]

Ahmad Sirhindi had originally declared the "reality of the Quran" (haqiqat-i quran) and "the reality of the Kaaba" (haqiqat-i ka'ba-yi rabbani) to be above the reality of Muhammad (haqiqat-i Muhammadi). This notion were deemed controversial by his contemporary, as it caused furor and opposition among certain Sufi followers and Ulama in Hejaz.[75] Sirhindi responded to their criticism by stating that while the reality of Muhammad is superior to any creature, he is not meant to be worshipped through Sujud or prostrations, in contrast with Kaaba, which God commanded to be the direction of prostration or Qibla.[76]

Legacy

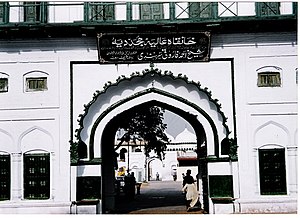

[edit]

The shrine of Ahmad Sirhindi, known as Rauza Sharif, is located in Sirhind, Punjab, India.[citation needed]

Ahmet Özel from Atatürk University has reported in his work on Diyanet İslâm Ansiklopedisi, el-alemgiriyye, That some of Ahmad Sirhindi works were compiled in Fatawa 'Alamgiri.[77]

There are at least 60 kind of Maktubat (letters) recorded from Ahmad Sirhindi which he delivered to various notables, officials, and shaykhs during his life.[78]

Due to his fervent orthodoxy, Ahmad Sirhindi's followers bestowed him the title of Mujaddid.[14][22] For his role to the medieval southeast Asia Islamic community, the Islamic politician Muhammad Iqbal called Ahmad Sirhindi as "the Guardian of the wherewithal the Community".[10] During 16th century, a Pantheism religious movements of Wahdat al wajood that are championed by Dara Shikoh, Sarmad Kashani, and Bawa Lal Dayal.[54] However, these movement were opposed by Ahmad Sirhindi, Khwaja Muhammad Masum and Ghulam Yahya.[54] Ahmad Sirhindi isnoted as being influential here as his release of strong criticism of Ibn Arabi pantheism caused the movement received significant setbacks.[46][79]

According to Mohammad Yasin in his work, A Social History of Islamic India, the impact of Ahmad Sirhindi in Muslim community in 17th century for reversing the spread of heterodox thinking was seen as huge success.[80] Yohanan Friedmann has noted that according to many modern historians and thinkers, the puritanical thought of Ahmad Sirhindi has inspired the religious orthodoxy of emperor Aurangzeb.[81][82] This was noted by how Ahmad Sirhindi managed to influence the successor of emperor Akbar, starting from Jahangir, into reversing Akbar's policies, such as lifting marriage age limits, mosque abolishments, and Hijra methodology revival which was abandoned by his father.[83] It is noted by historians that this influence has been significantly recorded during the conquest of Kangra under Jahangir, that at the presence of Ahmad Sirhindi who observed the campaign, the Mughal forces had the Idols broken, a cow slaughtered, Khutbah sermon read, and other Islamic rituals performed.[84] Further mark of Jahangir's departure from Akbar's secular policy was recorded by Terry, a traveller, who came and observed the Indian region between 1616 and 1619, where he found the mosques full of worshippers, the exaltation of Quran and Hadith practical teaching, and the complete observance of Fasting during Ramadan and Eid al-Fitr celebrations.[84]

Gerardus Willebrordus Joannes Drewes argues that the influences of Ahmad Sirhindi idea of Islamic reformation and anti Ibn Arabi's pantheism has spread as far as Aceh, with the indication of how Aceh Sultanate scholar Nuruddin ar-Raniri seems held the similar view with Ahmad Sirhindi regarding he rejection against Ibn Arabi.[85]

Abul A'la Maududi, modern Hanafite thinker and political activist, were recorded to quote Ahmad Sirhindi role in opposing the "religious impurities" which were introduced by Akbar earlier:

|

| Abul A'la Maududi[86] |

According to Chanfi Ahmed, many historians regards Ahmad Sirhindi as the pioneer of Islamic reformism of Salafism in seventeenth century India.[87] Although Chanfi Ahmed regards the movement were marked by Shah Waliullah Dehlawi instead.[87] Gamal al-Banna instead opined that Ahmad Sirhindi was influencing Shah Waliullah Dehlawi in reviving the science of Hadith in northern India.[88] Modern writer Zahid Yahya al-Zariqi has likened Ahmad Sirhindi personal view with Muhammad ibn Ali al-Sanusi, Ibn Taymiyya, Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya, Abd al-Razzaq al-San'ani, and Al-Shawkani, due to his orthodox stance, and his opposition to emperor Akbar in term of religious practice.[89] This view is also similar with the assessment of Salah Shu'air, an Egyptian writer, about the ideas of Sirhindi were similar with the Wahhabism movements which will rise two century after death of Ahmad Sirhindi,[90] for resurrecting and revival of religious discourses, which also influence in Shsh Waliullah Dehlawi.[91] While Aḥmad ʻArafāt Qāḍi from Cairo University also likened the though of Ahmad Sirhindi were similar with Ibn Taymiyyah.[92]

In field of Hadith scholarships, Ahmad Sirhindi also wrote commentary or sharh of Sahih al-Tirmidhi.[93]

Naqshbandi sufism

[edit]By the latter part of the nineteenth century, the consensus of the Naqshbandi community had placed the prophetic realities closer to God than the divine realities. The rationale for this development may have been to neutralize unnecessary discord with the large Muslim community whose emotional attachment to Muhammad was greater than any understanding of philosophical fine points.[94]

Ahmad Sirhindi criticize the practice of Khalwa or ascetism by calling it as heresy, due to no arguments that showed that the early generations of Muslims practiced it.[95]

Naqshbandi Sufis claim that Ahmad Sirhindi is descended from a long line of "spiritual masters" which were claimed by the order:[96]

- Muhammad, d. 11 AH, buried in Medina, Saudi Arabia (570/571–632 CE)

- Abu Bakar Siddique, d. 13 AH, buried in Medina, Saudi Arabia

- Salman al-Farsi, d. 35 AH, buried in Madaa'in, Saudi Arabia

- Qasim ibn Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr, d. 107 AH, buried in Medina, Saudi Arabia.

- Jafar Sadiq, d. 148 AH, buried in Medina, Saudi Arabia.

- Bayazid Bastami, d. 261 AH, buried in Bastaam, Iran (804 - 874 CE).

- Abu al-Hassan al-Kharaqani, d. 425 AH, buried Kharqaan, Iran.

- Abul Qasim Gurgani, d. 450 AH, buried in Gurgan, Iran.

- Abu ali Farmadi, d. 477 AH, buried in Tous, Khorasan, Iran.

- Abu Yaqub Yusuf Hamadani, d. 535 AH, buried in Maru, Khorosan, Iran.

- Abdul Khaliq Ghujdawani, d. 575 AH, buried in Ghajdawan, Bukhara, Uzbekistan.

- Arif Riwgari, d. 616 AH, buried in Reogar, Bukhara, Uzbekistan.

- Mahmood Anjir-Faghnawi, d. 715 AH, buried in Waabakni, Mawarannahr, Uzbekistan.

- Azizan Ali Ramitani, d. 715 AH, buried in Khwarezm, Bukhara, Uzbekistan.

- Mohammad Baba As-Samasi, d. 755 AH, buried in Samaas, Bukhara, Uzbekistan.

- Amir Kulal, d. 772 AH, buried in Saukhaar, Bukhara, Uzbekistan.

- Baha-ud-Din Naqshband Bukhari, d. 791 AH, buried in Qasr-e-Aarifan, Bukhara, Uzbekistan (1318–1389 CE).

- Sayyid Alauddin Atar Bukhari, buried in Jafaaniyan, Mawranahar, Uzbekistan.

- Yaqub al-Charkhi, d. 851 AH, buried in Tajikistan

- Khwaja Ahrar, d. 895 AH, buried in Samarkand, Uzbekistan.

- Muhammad Zahid Wakhshi, d. 936 AH, buried in Wakhsh, Malk Hasaar, Tajikistan

- Darwish Muhammad, d. 970 AH, buried in Samarkand, Uzbekistan

- Muhammad Amkanagi, d. 1008 AH, buried in Akang, Bukhara, Uzbekistan

- Khwaja Baqi Billah, d. 1012 AH, buried in Delhi, India

- Ahmad al-Farūqī al-Sirhindī (Ahmad Sirhindi, subject of this article)[96]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Biography of Ahmad Sirhindi in Urdu Language Archived 21 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Biography of Ahmad Sirhindi (Mujaddid Alf Sani)". Story of Pakistan website. June 2003. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Annemarie Schimmel. Islam in the Indian Subcontinent. ISBN 9004061177.

- ^ a b c d e M. Sharif 1966, p. 873-883.

- ^ Bruckmayr, Philipp (2020). "Salafī Challenge and Māturīdī Response: Contemporary Disputes over the Legitimacy of Māturīdī kalām". Die Welt des Islams. 60 (2–3). Brill: 293–324. doi:10.1163/15700607-06023P06. S2CID 225852485.

- ^ مقالات الإسلاميين في شهر رمضان الكريم. IslamKotob. p. 123. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ Algar, Hamid (2000). Imâm-i Rabbânî (in Turkish). Vol. 22. Istanbul: Turkish Diyanet Foundation. pp. 194–199.

- ^ Muhammad Ali Jihad (2002). معجم الأدباء من العصر الجاهلي حتى سنة 2002 - ج 6 - محمد علي جهاد - و [Dictionary of Writers from the Pre-Islamic Era until 2002 - Part 6 - Muhammad Ali Jihad] (Paperback). IslamKotob. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi at the Encyclopædia Britannica. "Shaykh Aḥmad Sirhindī, (born 1564?, Sirhind, Patiāla, India—died 1624, Sirhind), Indian mystic and theologian who was largely responsible for the reassertion and revival in India of orthodox Sunnite Islam as a reaction against the syncretistic religious tendencies prevalent during the reign of the Mughal emperor Akbar."

- ^ a b c d e f g h Irfan Habib (1960). "The Political Role of Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi and Shah Waliullah". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 23: 209–223. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44304065. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ Malik, Zubair & Parveen 2016, p. 158.

- ^ Malik, Zubair & Parveen 2016, p. 159-162.

- ^ Josef W. Meri, Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, (Routledge 1 Dec 2005), p 678. ISBN 0415966906

- ^ a b Glasse, Cyril (1997). The New Encyclopedia of Islam. AltaMira Press. p. 432. ISBN 90-04-10672-3.

- ^ a b c Annemarie Schimmel (2004, pp. 94, 132–133, 231)

- ^ a b Islamweb Fatwa center (2005). "نبذة عن الإمام أحمد الفاروقي". Islamweb (in Arabic). Abdullaah Al-Faqeeh. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

هذا.. وللوقوف على تفصيل أوسع لسيرة ذلك الإمام، ولبيان جهوده في الدعوة وملامح تجديده للدين، راجع ما كتبه عنه العلامة أبو الحسن الندوي في مؤلفه الحافل (رجال الفكر والدعوة في الإسلام)، حيث خصص الجزء الثالث بكامله للترجمة لذلك الإمام رحمه الله تعالى.

- ^ Ahmad 1964.

- ^ Friedmann 2000, New Delhi.

- ^ Haar & Friedmann 1992, Leiden.

- ^ Buehler 2011, Louisville, Kentucky.

- ^ Heehs 2002, p. 270.

- ^ a b American Academy of Arts and Sciences (May 2004). E. Marty, Martin; Scott Appleby, R. (eds.). Fundamentalisms Comprehended (Paperback). University of Chicago Press. p. 300. ISBN 9780226508887. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ N. Hanif (2000). Biographical Encyclopaedia of Sufis South Asia. Prabhat Kumar Sharma, for] Sarup & Sons. p. 365. ISBN 9788176250870. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

Ahmad Sirhindi generally known as Mudjaddid - i Alf - Ithani an eminent divine and mystic of Muslim India, who ... Umar b . al - Khattab . He received his early education from his father and later pursued a course of higher stud- ies ...

- ^ a b Saiyid Athar Abbas Rizvi (1965). Muslim Revivalist Movements in Northern India in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Agra University. pp. 196, 202. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- ^ Itzchak Weismann, The Naqshbandiyya: Orthodoxy and Activism in a Worldwide Sufi Tradition, Routledge (2007), p. 62

- ^ S.Z.H. Jafri, Recording the Progress of Indian History: Symposia Papers of the Indian History Congress, 1992-2010, Primus Books (2012), p. 156

- ^ Khwaja Jamil Ahmad, One Hundred greater Muslims, Ferozsons (1984), p. 292

- ^ Sufism and Shari'ah: A study of Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi's effort to reform Sufism, Muhammad Abdul Haq Ansari, The Islamic Foundation, 1997, p. 11.

- ^ "Mujaddid Alf e Sani The first of the great reformers, Sheikh Ahmad Sarhindi al-Farooqi an-Naqshbandi". June 2003.

- ^ Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, Routledge, 2006, p. 755.

- ^ a b c John F. Richards (1993). The Mughal Empire Part 1, Volume 5 (Paperback). Cambridge University Press. pp. 98–100. ISBN 9780521566032. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ Ali Al-Tantawi (1998). رجال من التاريخ (in Arabic). Dar Al-Manara - Jeddah. p. 232. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ Hasan Murtaza (1946). "7. Letters of Sheikh Ahmad. (A New Source of Historical Study) [1563—1624 A. D.]". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 9: 273–281. JSTOR 44137073.

n : It v as written from the Imperial Camp. It shows that the Imam was held in esteem in the Imperial Court, used to attend it daily and by his daily debates there used to counter-act the beliefs and doctrines pre- valent in court. /It almost gives a list of the beliefs and doctrines which were discussed, criticised and ridiculed in the Court. T

- ^ "Mujaddid Alf Sani's Movement". Story of Pakistan website. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

- ^ عثمان نوري طوبّاش. "الإمام الرباني أحمد الفاروقي السرهندي رحمه الله (4651-4261م)". osmannuritopbas (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 1 October 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2024.

Abu Al-Hasan Al-Nadawi: Imam Al-Rabbani

- ^ a b Abdul Aziz Al-Badri (15 October 2019). Hitam Putih Wajah Ulama dan Penguasa (ebook) (in Indonesian). Penerbit Darul Falah. p. 229. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

... Sirhindi meminta izin kepada raja yang shalih itu untuk kembali ke negerinya. Diapun diberi izin dengan penuh ... salaf, bahkan di setiap waktu, Allah selalu. 5 Ibid., hal 25. Beliau meninggal pada tahun 1034 berusia 63 tahun. 1 Thabaqaat ...

- ^ Ahmad Hasan Dani; Vadim Mikhaĭlovich Masson (1992). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in contrast : from the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century (Hardcover). UNESCO. p. 314. ISBN 978-92-3-103876-1. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

... Vaishnavite divine Chitrarup (d. 1637–8) and put the anti-Shicite cleric Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi (d. 1624) in prison ...

- ^ الدين والدولة في تركيا المعاصرة (ebook) (in Arabic). Al Manhal. 2010. p. 39. ISBN 979-6-500-16589-9. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

١٠-١٠٣٧هـ/١٦٠٥-١٦٢٧م) فبايعه خلق كثير على متابعة السنة واجتناب البدعة ، وطفق الاعيان والامراء يرجعون إلى الإسلام ، ويثوبون إلى رشدهم ، ولما سجنه جهانكير اهتدى المسجونون ...

- ^ a b غازي، محمود احمد (2009). تاريخ الحركة المجدّدية دراسة تاريخية تحليلية لحياة الامام المجدد احمد بن عبد الاحد السرهندي المعروف بمجدد الالف الثاني : وعمله الاصلاحي التجديدي الذي قام به في شبه القارة مع ترجمة لبعض رسائل وكتابه المختارة (in Arabic). دار الكتب العلمية،. pp. 224–225. ISBN 9782745162656. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

... . إن الخواجة محمد المعصوم وزملاءه أقاموا في الحرمين الشريفين لمدة تقارب سنتين كاملتين. واستمرت خلال هذه المادة المعارك الشديدة بين الأمير أورنكزيب الذي كان ك الدامية الطويلة، وتمكن أورنكزيب من الاستيلاء على عرش الدولة ومناداته ملكا للبلاد. ولما رجع الخواجة محمد المعصوم إلى الهند ووصل إلى ميناء سورت في نهاية عام 1069 هـ كانت الاوضاع قد تغيرت تماما وكانت القوى الإسلامية منتصرة وكان الامير أورنكزيب متمكنا على العرش باسم الامبراطور محمد أورنك زيب عالمكير. إليهم رسالة يخبرهم فيها بنجاحه وهزيمة معسكر دارا شكوه". ويروي أن الملك أورنكزيب عالمكير أصدر

- ^ Ahmad, Imtiaz (2002). "Mughal Governors of Bihar Under Akbar and Jahangir". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 63. Indian History Congress: 285. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44158096. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ Ahmad 1961, p. 261.

- ^ a b c d Ahmad al-Faruqi Sirhindi (11 March 2016). Al-muntakhabaat Min Al-maktubaat (in Arabic). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 589. ISBN 978-1530512799.

- ^ a b Babar Sultan Asadullah Ph.D, Taswar Hussain Ph.D & Uzma Akhlaq Assistant professor (2021, p. 41)

- ^ Babar Sultan Asadullah Ph.D, Taswar Hussain Ph.D & Uzma Akhlaq Assistant professor (2021, p. 43)

- ^ a b عبيد الرحمن (2022). فقه البدعة في الشريعة الإسلامية - دراسة مقارنة لمفهومها وأحكامها وتصفية الاختلافات (ebook) (in Arabic). Dar Al Kotob Al Ilmiyah دار الكتب العلمية. p. 32. ISBN 9782745196279. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

... ليس منه " فإن القياس من أمر الدين ، وفي ذلك يقول الإمام المجدد الشيخ أحمد السرهندي - رحمه الله - : أما القياس والاجتهاد فليس من البدعة في شيء فإنه مظهر أمر ثابت لا مثبت أمر زائد ) . ويقول العلامة أبو سعيد الخادمي - رحمه الله - : إن كان - : ...

- ^ a b c d Ganeri, Jonardon, ed. (12 October 2017). The Oxford Handbook of Indian Philosophy 2017 (ebook). Oxford University Press. p. 660. ISBN 9780190668396. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

... pantheistic school of thought; Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi, Khwaja Muhammad Masum and Ghulam Yahya belonged to the other school ... with the advent of Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi (ob. 1624) pantheistic ideas received a setback and his powerful ...

- ^ Samee Ullah Bhat (10 March 2019). Islamic Historiography Nature and Development (ebook). Educreation Publishing. pp. 110, 114–115. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ Ahmed Sirhindi Faruqi. "7: The alams and everything were created from nothing. Greek philosophers.". Maktubat Imam Rabbani (Shaykh Ahmed Sirhindi) (in English and Punjabi). Archived from the original on 10 August 2009. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ Ahmed Sirhindi Faruqi. "3: It is not permissible to confine the meanings in Qur'an al-karim within philosophers' views.". Maktubat Imam Rabbani (Shaykh Ahmed Sirhindi) (in English and Punjabi). Archived from the original on 10 August 2009. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ Octavio Paz (26 February 2015). In Light of India (ebook). February 26, 2015. ISBN 9781784870706. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

... Shaikh Aḥmad Sirhindi, (d. A.D. 1624). According to Jahangir, he sent his Khalifahs to every town and city of the country . He was opposed to the pantheistic philosophy ( waḥdat - ul - wujud ) on which the entire structure of ...

- ^ India. Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (1973). The Gazetteer of India: History and culture. Government of India Press. p. 428. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

... Shaikh Aḥmad Sirhindi, (d. A.D. 1624 ). According to Jahangir, he sent his Khalifahs to every town and city of the country . He was opposed to the pantheistic philosophy ( waḥdat - ul - wujud ) on which the entire structure of ...

- ^ Anis Ahmad (2022). "The Muslim Reawakening in the 19th Century Pak-Hind Sub-Continent: An Overview". Hamdard Islamicus. 45 (1). Riphah International University: 13. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- ^ Shankar Nair (28 April 2020). Translating Wisdom Hindu-Muslim Intellectual Interactions in Early Modern South Asia (Paperback). University of California Press. p. 92. ISBN 9780520345683. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

... Aḥmad Sirhindī, on the other, supposedly representing the voice of triumphalist ... Ahmad Sirhindi, Khwaja Muhammad Masum and Ghulam Yahya belonged to the other school . . . . [W]ith the advent of Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi (ob. 1624) pantheistic ...

- ^ a b c Everett Jenkins, Jr. (7 May 2015). The Muslim Diaspora (Volume 2, 1500-1799) A Comprehensive Chronology of the Spread of Islam in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas (ebook). McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. p. 151. ISBN 9781476608891. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

... Sirhindi's doctrines. Ahmad Sirhindi's doctrines condemn pantheism, particularly the pantheism which was a component of Hinduism. With the ascension of doctrinally strict Aurangzeb, conflicts arose between the Hindu subjects and Muslim ...

- ^ Abdul Haq Ansari (2001, p. 589)

- ^ Chittick, William (2012). "Wahdat al-Wujud in India" (PDF). Ishraq: Islamic Philosophy Yearbook 3: 29–40 [36].

- ^ "Shaykh Aḥmad Sirhindī". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ Annemarie Schimmel, Islam in the Indian Subcontinent, p. 94. ISBN 9004061177

- ^ Ahmed Sirhindi Faruqi. "33: Souls show themselves in men's figures. What metempsychosis is..". Maktubat Imam Rabbani (Shaykh Ahmed Sirhindi) (in English and Punjabi). Archived from the original on 10 August 2009. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ Yohanan Friedmann, "Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi: An Outline of His Thought and a Study of His Image in the Eyes of Posterity", Chapter 5, Section 3, Oxford University Press (2001).

- ^ Tarana Singha (1981). Sikh Gurus and the Indian Spiritual Thought. University of California. p. 74.

- ^ Syed Athar Abbas Rizvi, "Muslim Revivalist Movements in Northern India", p. 250, Agra University Press, Agra, (1965).

- ^ Mubarak Ali Khan (1992). Historian's dispute. Progressive Publishers; Lahore, Pakistan. p. 77. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

He believed that the Shias, Mahdawis, and the mystics were responsible for the decline of Sunni Muslim in India

- ^ Gandhi, Surjit Singh (2007). History of Sikh gurus retold. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. p. 431. ISBN 978-81-269-0859-2. OCLC 190873070.

- ^ Singh, Rishi (2015). State Formation and the Establishment of Non-Muslim Hegemony : Post-Mughal 19th-century Punjab. New Delhi: SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-93-5150-504-4. OCLC 1101028781.

- ^ Gaur, I. D. (2008). Martyr as bridegroom : a folk representation of Bhagat Singh. New Delhi, India: Anthem Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-84331-348-9. OCLC 741613158.

- ^ https://punjab.global.ucsb.edu/sites/default/files/sitefiles/journals/volume12/no1/3_singh.pdf page 6.

- ^ "When Emperors turned on Gurus". 17 November 2017.

- ^ "The Martyrdom Of Guru Arjan Dev Ji" – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Abdul Haq Ansari (2001, p. 673)

- ^ Arthur F. Buehler (2014). Revealed Grace: The Juristic Sufism of Ahmad Sirhindi (1564-1624). Fons Vitae. ISBN 978-1-891785-89-4. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- ^ Shams ad-Din Salafi al-Farghani (1996). Efforts of Hanafi scholars to invalidate the doctrines of Grave worshippers (in Arabic). دار الصميعي. p. 164. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

... لمحمد مراد المنزاوي ترجمة المكتوبات لأحمد السرهندي المعروف بالرباني ٢٥/٣ ، ومجموعة الفتاوى للكنوي ٤٥/٢ ، وصيانة الإنسان ١٥٦ ، وفتح المنان ٤٥٢-٤٥٣ . ( ۳ ) رواه مسلم ٥٥/١ عن عثمان رضي الله عنه . ( ٤ ) راجع المرقاة ۱ / ۲۰۱ للقاري وفتح ...

- ^ a b Digby, Simon (1975). "Reviewed work: Shaykh Aḥmad Sirhindī: An Outline of His Thought and a Study of His Image in the Eyes of Posterity, Yohanan Friedmann". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 38 (1): 177–179. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00047406. JSTOR 614232.

- ^ Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi: an outline of his thought and a study of his image in the eyes of posterity, McGill-Queen's University Press, 1971, p.xiv Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 38, No. 1 (1975), pp. 177-179

- ^ Sirhindi, Ahmad (1984). Mabda'a wa-ma'ad. Karachi: Ahmad Brothers. p. 78.

- ^ Ahmad, Nur (1972). Maktubat-i Imam Rabbani 3 vols. Ed (in Arabic). Karachi: Education Press. pp. 147( letter 124).

- ^ Sardella, Ferdinando; Jacobsen, Knut A., eds. (2020). Handbook of Hinduism in Europe (2 Vols). Brill. p. 1507. ISBN 9789004432284. Retrieved 25 April 2024.

- ^ "Maktubat Imam-e-Rabbani" (in Arabic, English, Persian, Urdu, Turkish, and Malay). Translated by Muhammad Saeed Ahmed Naqshbandi. Karachi: Madina Publishing Company. Archived from the original on 10 August 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2024.

- ^ Shankar Nair (2020). Translating Wisdom Hindu-Muslim Intellectual Interactions in Early Modern South Asia. University of California Press. p. 92. ISBN 9780520345683. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Malik, Zubair & Parveen 2016, p. 159, A Social History of Islamic India; Yasin; p.145.

- ^ Gerhard Bowering; Mahan Mirza; Patricia Crone (2013). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought (Hardcover). Princeton University Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780691134840. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ Malik, Zubair & Parveen 2016, p. 162-163.

- ^ Malik, Zubair & Parveen 2016, p. 158-161.

- ^ a b Malik, Zubair & Parveen 2016, p. 159-161.

- ^ Zulkefli Aini; Che Zarrina Sa'ari (2014). "Usaha Dakwah Nur al-Din al-Raniri Menentang Kesesatan Kaum Wujudiyyah dalam Kitab Ma'a al-Hayah li Ahl al-Mamat". Afkar: Jurnal Akidah & Pemikiran Islam (in Malay). 15 (1): 20–21. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

doktrin yang dibawa oleh Ibn `Arabi dengan golongan muslim yang dikategorikan sebagai ortodoks.... tindakan Nur al-Din al- Raniri itu dari perspektif yang lebih luas atau apa yang diistilahkannya sebagai "from an international point of view".... tindakan Nur al-Din al-Raniri itu merupakan kesan dari reformasi politik dan agama yang dibawa oleh Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi yang telah merebak ke dunia Islam terutama di Aceh. .... Drewes melihat perkembangan di Shahr-I Nawi yang menjadi destinasi Hamzah Fansuri ... Lihat Drewes dan Brakel, The Poems of Hamzah Fansuri

- ^ Malik, Jamal, ed. (2007). Madrasas in South Asia Teaching Terror? (ebook). Taylor & Francis. p. 146. ISBN 9781134107636. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Sheykh Wali Allāh Dihlawi (1703–63)". West African ʿulamāʾ and Salafism in Mecca and Medina Jawāb Al-Ifrῑqῑ - The Response of the African. Brill. 10 March 2015. ISBN 9789004291942. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

Though many historians attribute the beginning of Islamic reformism in India to the teachings of Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi (Sirhind) in the seventeenth century, in fact it was the teaching of Shaykh Wali Allāh ...

- ^ Gamal al-Banna (2006). رِسَالَــة إِلَى الدَّعَوَاتِ الإِسْلامِيَّة من دعوة العمل الإسلامي (ebook) (in Arabic). كتب عربية. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

جمال البنا. وخلف الإمام المجاهد أحمد السرهندي في قيادة الدعوة الإسلامية الشيخ عبد الحق الدهلوي ( 1 ) الذي أحيا علم الحديث في شمال الهند ، وشرح مشكاة المصابيح " بالعربية والفارسية .. وكانت جهود العلماء قبله مُنصبة على فروع الفقه الحنفي ... ... العلماء قبله منصبة على فروع الفقه الحنفى والمنطق وعلم الكلام ثم ظهر الإمام ولى الله الدهلوى ( ١١١٤ – ١١٧٦ هـ ) مؤلف « حجة الله البالغة » ، أحد غرر المراجع الإسلامية ، والكتاب الموجز الإنصاف في بيان سبب الاختلاف .. ووضع ولى الله الدهلوى ...

- ^ زاهد يحيى زرقي (1990). بين السلفية والصوفية الاعتقاد الصحيح والسلوك السليم (in Arabic). the University of California. p. 141. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

... دور لا يقل عن دور ابن عبدالوهاب وقد كانت طريقته صوفية سلفية . واذا أردنا ان نذكر فضائل ائمة السلفية وجهاد ابن تيمية وابن قيم الجوزية ومحمد بن عبدالوهاب والشوكاني والصنعاني وغيرهم فيجب أن لا ننسى دور الامام أحمد السرهندى ( ١٠٣٤ هـ ) في مقاومته لفتنة الملك اكبر ولا ننسى دور الشيخ السنوسي في جهاده للايطاليين ودور الشيخ عبد القادر الجزائري في جهاده ...

- ^ K. Mishra 2019, p. 10, The strongest proponent of revivalism during the Mughal period was Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi, a Sufi of the Naqshbandi order, who had adopted the title of Mujaddid (renovator), and who may be regarded as the founder of a revivalist movement with close parallels to Wahhabism two centuries later. As.

- ^ Salah Shair (2022). الطائفية والتقسيم.. أخطار الصراع الطائفي بمصر والعالم العربي (طبعة منقحة ومزيدة) (in Arabic). وكالة الصحافة العربية. pp. 129–130. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

... وعلى ضوء من سيرتها، حركات ومحاولات كثيرة كدعوة الشوكانى فى بلاد اليمن، ودعوة السيد السنوسى فى بلاد أفريقيا، العربى والإسلامى. وربما تعود شهرة حركة الشيخ محمد بن عبد الوهاب كأول حركة تجديدية فى الخطاب الدينى الحديث، إلى أنها لاقت نجاحا شديدا ... ... محمد بن عبد الوهاب وقامت الحركة الوهابية بهدف بعث وإحياء الخطاب الديني وربما سبقتها بعض الحركات كدعوة شاه ولى الله الدهلوى في الهند اعتمادا على حركة الشيخ أحمد السرهندى من قبله وعبد القادر البغدادي في مصر ، والنابلسي في دمشق ، والشوكاني ...

- ^ Aḥmad ʻArafāt Qāḍī (1996). الفكر التربوي عند المتكلمين المسلمين ودوره في بناء الفرد والمجتمع (in Arabic). الهيئة المصرية العامة للكتاب،. p. 456. ISBN 9789770150177. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

... في الهند وإفريقيا والعالم العربي مشرقة ومغربه ، ولقد سبقت هذه الحركات هواجس فكرية ومواقف عملية كانت إرهاصا وتبشيرا بهذا الفكر الحديث أكثر منها بداية حقيقية له على يد الشيخ أحمد السرهندي في الهند ، وصدر الدين الشيرازي في فارس والشيخ أحمد ...... على تراث ابن تيمية و ابن حنبل ، مناديا بعودة جديدة صادقة إلى الكتاب والسنة ، فتلقف ذلك دعاة كثيرون في الهند و ... الحديث ، أكثر منها بداية حقيقية له على يد الشيخ أحمد السرهندي في الهند ، و صدر الدین الشيرازي في فارس ، و الشيخ أحمد ...

- ^ Muḥammad ʻAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʻAbd al-Raḥīm Mubārakfūrī; Saʻūd ʻAlī (1990). Tuḥfat al-aḥwadhī bi-sharḥ Jāmiʻ al-Tirmidhī Volume 11 (in Arabic). al-Maktabah al-Ashrafīyah. p. 333. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

... بلفظه قلت : قولها هذا ليس بصحيح . أما قول السرهندي هرجاکه مصنف لفظ بعض اهل کوفه ذکر کرده مراد امام ابي حنيفة باشد فباطل قطعاً ، ألا ترى أن الترمذي روى في باب ما جاء أنه يبدأ بمؤخر الرأس حديث الربيع بنت معوذ : أن النبي صلى الله عليه وسلم ...

- ^ Buehler, Arthur (1998). Sufi Heirs of the Prophet: the Indian Naqshbandiyya and the rise of the mediating sufi shaykh. Columbia, S.C USA: University of South Carolina Press. pp. 246–247 (Appendix 2). ISBN 1-57003-201-7.

- ^ Warjio; Heri Kusmanto; Siti Nur Aini (2019). Ibrahim, Azrin; Farhana Mhd Poad, Afifi; Atikah Mohd Khairuddin, Nur (eds.). "Kampung Babussalam: A Model of Spiritual Citizenship Development Based on Tareqah Naqsyabandiyah Tradition" (PDF). 14th ISDEV International Islamic Development Management Conference (IDMAC2019). Gelugor, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia: Centre for Islamic Development Management Studies (ISDEV); Universiti Sains Malaysia: 361, ...Ahmad Sirhindi called this practice a bid'ah because there was no argument that showed that the early generations of Muslims practiced it..18 Fuady Abdullah. Loc.cit. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Family Lineage of Ahmad Sirhindi". August 2009. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

Bibliography

[edit]- Abdul Haq Ansari (2001). Merajut Tradisi Syari'ah Sufisme: "Mengkaji Gagasan Mujaddid Syeikh Ahmad Sirhindi" [Weaving the Sharia Tradition of Sufism: "Examining the Ideas of Mujaddid Sheikh Ahmad Sirhindi"] (in Indonesian). Translated by Achmad Nashir Budiman. Jakarta, Indonesia: Raja Grafindo Persada. ISBN 979-421-236-9. Retrieved 31 August 2024.

- Annemarie Schimmel (2004). K. Waghmar, Burzine (ed.). The Empire of the Great Mughals: History, Art and Culture (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Reaktion Books. ISBN 1861891857. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- Dr. Burhan Ahmad Faruqi, Mujaddid’s Conception of Tawhid, 1940

- Shari'at and Ulama in Ahmad Sirhindi's Collected Letters by Arthur F. Buehler.

- Heehs, Peter (2002). Indian Religions: A Historical Reader of Spiritual Expression and Experience. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-3649-4.

- Malik, Adnan; Zubair, Muhammad; Parveen, Uzman (2016). "Effects of social reforms of shaykh Ahmad sirhindi (1564-1624) on muslim society in the sub continent". Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities. 55 (2). University of Karachi: 155–164. doi:10.46568/jssh.v55i2.70. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- Ahmad, Aziz (1964). Studies in Islamic Culture in the Indian Environment. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195644646.

- Friedmann, Yohannan (2000). Shaikh Aḥmad Sirhindī: An Outline of His Thought and a Study of His Image in the Eyes of Posterity. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195652398.

- Haar, J.G.J. ter.; Friedmann, Yohanan (1992). "Follower and Heir of the Prophet: Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi (1564-1624) as Mystic". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 114 (3). Leiden: Van Het Oosters Instituut: 460. doi:10.2307/605091. JSTOR 605091. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- Buehler, Arthur (2011). Revealed Grace: The Juristic Sufism of Aḥmad Sirhindi (1564-1624). Louisville, Kentucky: Fons Vitae. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- K. Mishra, Ravi (2019). "Islam in India and the Rise of Wahhabism". India International Centre Quarterly. 46 (2). India International Centre: 1–30. JSTOR 26856495. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- M. Sharif, M. (1966). A History of Muslim Philosophy Volume 2. Kempten, Germany: Pakistan Philosophical Congress; Allgauer Heimatverlag GmbH. pp. 873–883. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- Ahmad, Aziz (1961). "RELIGIOUS AND POLITICAL IDEAS OF SHAIKH AHMAD SIRHINDĪ". Rivista degli studi orientali. 36. Sapienza - Universita di Roma: 259–270. JSTOR 41879388. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- Sajida S. Alvi (1989). "Religion and State during the Reign of Mughal Emperor Jahǎngǐr (1605-27): Nonjuristical Perspectives". Studia Islamica. 69 (69). Brill: 95–119. doi:10.2307/1596069. ISSN 0585-5292. JSTOR 1596069. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- Babar Sultan Asadullah Ph.D; Taswar Hussain Ph.D; Uzma Akhlaq Assistant professor (2021). "Religious and Political Reforms and Reconstruction of Mujaddid Alf e Thani in Muslim of sub-continent". Al Aijaz Research Journal of Islamic Studies & Humanities. 5 (3). Al Khadim Foundation. ISSN 2707-1219. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

External links

[edit]- Iqbal Sabir (1990). Ahmad Nizami, Khaliq (ed.). "The Life and Times of Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi". The Life and Times of Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi. Centre of Advanced Study – Department of History – Aligargh Muslim University. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- Biography of Hadrat Imâm Rabbânî

- Biography of Imam Rabbani Ahmad al-Faruqi as-Sirhindi (from the Naqshbandi-Haqqani Sufi Order).

- Translations of Imam Rabbani's Letters in various languages

- 1564 births

- 1624 deaths

- 17th-century Indian Muslims

- 17th-century Indian philosophers

- Naqshbandi order

- Muslim critics of atheism

- People from Fatehgarh Sahib

- Sunni Sufis

- Islamic philosophers

- Hanafi fiqh scholars

- Hanafis

- Maturidis

- Mujaddid

- Hashemite people

- Indian Sufi saints

- 16th-century jurists

- 17th-century jurists

- Critics of Ibn Arabi

- Indian Sunni Muslim scholars of Islam