Hypsilophodontidae

| Hypsilophodontidae Temporal range: Early Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

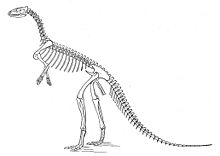

| Hypsilophodon skeleton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Neornithischia |

| Clade: | †Clypeodonta |

| Family: | †Hypsilophodontidae Dollo, 1882[1] |

| Subgroups[2] | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Hypsilophodontidae (or Hypsilophodontia) is a traditionally used family of ornithopod dinosaurs, generally considered invalid today. It historically included many small bodied bipedal neornithischian taxa from around the world, and spanning from the Middle Jurassic until the Late Cretaceous. This inclusive status was supported by some phylogenetic analyses from the 1990s and mid 2000s,[3][4] although there have also been many finding that the family is an unnatural grouping which should only include the type genus, Hypsilophodon, with the other genera being within clades like Thescelosauridae and Elasmaria.[5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15] A 2014 analysis by Norman recovered a grouping of Hypsilophodon, Rhabdodontidae and Tenontosaurus, which he referred to as Hypsilophodontia.[2] That clade is formally defined in the PhyloCode as "the smallest clade within Ornithopoda containing Hypsilophodon foxii and Tenontosaurus tilletti provided it does not include Iguanodon bernissartensis".[16] All other analyses from around the same time have instead found these latter taxa to be within Iguanodontia.[12][17] The family Hypsilophodontidae is formally defined in the PhyloCode by Daniel Madzia and colleagues in 2021 as "the largest clade containing Hypsilophodon foxii, but not Iguanodon bernissartensis and Rhabdodon priscus".[16]

Linnaean usage

[edit]

Hypsilophodontidae was named originally in 1882 by Louis Dollo, as a family to include Hypsilophodon and other small ornithopods with a single row of teeth, four pedal digits, and a rhomboid sternum. For several decades after its naming the family only included Hypsilophodon.[4] In 1911 Karl von Zittel published a textbook on vertebrate classifications, in which he included multiple genera in "Hypsilophodontidae" (sic for Hypsilophodontidae[18]), including Hypsilophodon, Nanosaurus, Laosaurus and Dryosaurus. Zittel considered the family to unite all taxa that lacked premaxilla teeth, had a single row of maxilla teeth, neck vertebrae which have flat articulations or a flat front and round back, fused sacral vertebrae, a femur shorter than the tibia, 5 fingered manus' and 4 toed peds.[19] Thescelosaurus was named in 1913 by Charles Gilmore, and its skeleton was described in detail by the same author in 1915. Gilmore had originally classified Thescelosaurus within Camptosauridae, but in the 1915 description he determined that it shared far more features with Hypsilophodontidae. He reclassified Laosaurus, Nanosaurus and Dryosaurus in the family Laosauridae, leaving only Thescelosaurus and Hypsilophodon in Hypsilophodontidae. The characteristics of the family were also re-analysed, and Gilmore showed that the premaxilla actually had teeth, a characteristic of the family; the 3rd manus digit had 4 phalanges; the femur was either shorter or longer than the tibia; and dorsal ribs had only a single articulation point.[18]

The first expansive analysis on the relationships of Hypsilophodontidae was that of Swinton in 1936, during a redescription of Hypsilophodon from new specimens. The possible hypsilophodonts Geranosaurus and Stenopelix were removed from the clade (then the subfamily Hypsilophodontinae), and considered to be intermediate basal ornithopods, as there were no features linking them to Hypsilophodon. Thescelosaurus was considered within the family, because of the large number of shared features, as well as Dysalotosaurus, from the Kimmeridgian of Tanzania. Laosaurus and Dryosaurus were not considered hypsilophodonts because of their lack of distinguishable features, as Swinton concluded that they were probably in the family Laosauridae, intermediate between Hypsilophodontidae and Iguanodontidae, and were probably synonyms of each other as well.[20] Charles M. Sternberg (1940) considered there to be multiple genera within the family, all sharing fully enamelled teeth, divided into two subfamilies, Hypsilophodontinae and Thescelosaurinae. Within Hypsilophodontinae–grouped by a longer scapula, thinner forelimb and femora shorter than tibiae–Sternberg included Hypsilophodon, Dysalotosaurus, and Parksosaurus (renaming of Thescelosaurus warreni). Only Thescelosaurus was included in Thescelosaurinae, as it had a tibia shorter than the femur.[21]

Peter M. Galton in 1972 re-studied the relationships of taxa within Ornithischia. Thescelosaurus was removed from Hypsilophodontidae because of its short limbs, meaning it was probably not cursorial, unlike all other hypsilophodonts. The presence of premaxilla teeth, once used to diagnose the group, was found to be present in unrelated taxa like Heterodontosaurus, Protoceratops and Silvisaurus. Galton made Hypsilophodontidae paraphyletic, as he considered Thescelosaurus to be a hypsilophodont, but excluded it from the family Hypsilophodontidae. The phylogenetic hypothesis of Galton is shown below. Taxa considered hypsilophodontids are enclosed by green.[22]

Cladistic usage

[edit]Question of monophyly

[edit]In 1992 David Weishampel and Ronald Heinrich reviewed the systematics and phylogenetics of Hypsilophodontidae. Hypsilophodontidae was supported as a monophyletic clade that encompassed "thescelosaurids", Hypsilophodon and Yandusaurus. The family was diagnosed by the absence of ridges that end as denticles in teeth (reversed in Hypsilophodon); presence of a single central ridge on dentary teeth; ossified sternal plates on torso ribs; and a straight and unexpanded shape of the prepubis. Their resulting cladogram is reproduced below:[4]

The following cladogram of hypsilophodont relationships depicts the paraphyletic hypotheses; the "natural Hypsilophodontidae" hypothesis has been falling out of favor since the mid-late 1990s. It is after Brown et al. (2013), the most recent analysis of hypsilophodonts.[17] Ornithischia, Ornithopoda, and Iguanodontia were not designated in their result, and so are left out here. Additional ornithopods beyond Tenontosaurus are omitted. Dinosaurs traditionally described as hypsilophodonts are found from Agilisaurus or Hexinlusaurus to Hypsilophodon or Gasparinisaura.

unnamed

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Norman's Hypsilophodontia

[edit]A more recent alternate phylogeny, by Norman in 2014, resolved a monophyletic Hypsilophodontia (the family Hypsilophodontidae was not used because of its history). Hypsilophodon grouped with Rhabdodontidae and Tenontosaurus.[2]

Other research

[edit]In one analysis in her 2022 review of iguanodontian phylogenetic relationships, Karen E. Poole recovered a large Hypsilophodontidae as the sister taxon of Iguanodontia, which consisted of several "traditional" hypsilophodontids, as well as Thescelosauridae. The Bayesian topology of her phylogenetic analyses is shown in the cladogram below:[23]

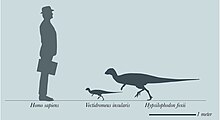

In 2023, Longrich et al. described Vectidromeus as a new genus of hypsilophodontid. Although they did not perform a phylogenetic analysis, they suggested that, since other taxa previously assigned to Hypsilophodontidae had subsequently been moved to other groups, Vectidromeus and Hypsilophodon remained as the only members of the clade.[24]

References

[edit]- ^ Dollo, L. (1882). "Première note sur les dinosauriens de Bernissart". Bulletin du Musée d'Histoire Naturelle de Belgique. 1: 161–180.

- ^ a b c Norman, D.B. (2014). "On the history, osteology, and systematic position of the Wealden (Hastings group) dinosaur Hypselospinus fittoni (Iguanodontia: Styracosterna)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 173: 92–189. doi:10.1111/zoj.12193.

- ^ Sues, Hans-Dieter; Norman, David B. (1990). "Hypsilophodontidae, Tenontosaurus, Dryosauridae". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 498–509. ISBN 978-0-520-06727-1.

- ^ a b c Weishampel, David B.; Heinrich, Ronald E. (1992). "Systematics of Hypsilophodontidae and Basal Iguanodontia (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda)" (PDF). Historical Biology. 6 (3): 159–184. doi:10.1080/10292389209380426.

- ^ Scheetz, Rodney D. (1998). "Phylogeny of basal ornithopod dinosaurs and the dissolution of the Hypsilophodontidae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 18 (3, Suppl): 1–94. doi:10.1080/02724634.1998.10011116.

- ^ Winkler, Dale A.; Murry, Phillip A.; Jacobs, Louis L. (1998). "The new ornithopod dinosaur from Proctor Lake, Texas, and the deconstruction of the family Hypsilophodontidae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 18 (3, Suppl): 87A. doi:10.1080/02724634.1998.10011116.

- ^ Buchholz, Peter W. (2002). "Phylogeny and biogeography of basal Ornithischia". The Mesozoic in Wyoming, Tate 2002. Casper, Wyoming: The Geological Museum, Casper College. pp. 18–34.

- ^ Weishampel, David B.; Jianu, Coralia-Maria; Csiki, Z.; Norman, David B. (2003). "Osteology and phylogeny of Zalmoxes (n.g.), an unusual euornithopod dinosaur from the latest Cretaceous of Romania". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 1 (2): 1–56. doi:10.1017/S1477201903001032. S2CID 86339025.

- ^ Norman, David B.; Sues, Hans-Dieter; Witmer, Larry M.; Coria, Rodolfo A. (2004). "Basal Ornithopoda". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 393–412. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- ^ Varricchio, David J.; Martin, Anthony J.; Katsura, Yoshihiro (2007). "First trace and body fossil evidence of a burrowing, denning dinosaur". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 274 (1616): 1361–1368. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.0443. PMC 2176205. PMID 17374596.

- ^ Boyd, Clint A.; Brown, Caleb M.; Scheetz, Rodney D.; Clarke, Julia A. (2009). "Taxonomic revision of the basal neornithischian taxa Thescelosaurus and Bugenasaura". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (3): 758–770. doi:10.1671/039.029.0328. S2CID 84273584.

- ^ a b Boyd, Clint A. (2015). "The systematic relationships and biogeographic history of ornithischian dinosaurs". PeerJ. 3 (e1523): e1523. doi:10.7717/peerj.1523. PMC 4690359. PMID 26713260.

- ^ Gasulla, José Miguel; Escaso, Fernando; Narváez, Iván; Ortega, Francisco; Sanz, José Luis (2015). "A New Sail-Backed Styracosternan (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the Early Cretaceous of Morella, Spain". PLOS ONE. 10 (12): e0144167. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1044167G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0144167. PMC 4691198. PMID 26673161.

- ^ Butler, Richard J.; Smith, Roger M.H.; Norman, David B. (2007). "A primitive ornithischian dinosaur from the Late Triassic of South Africa, and the early evolution and diversification of Ornithischia". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 274 (1621): 2041–6. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0367. PMC 2275175. PMID 17567562.

- ^ Butler, Richard J.; Upchurch, Paul; Norman, David B. (2008). "The phylogeny of the ornithischian dinosaurs". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 6 (1): 1–40. doi:10.1017/S1477201907002271. S2CID 86728076.

- ^ a b Madzia, D.; Arbour, V.M.; Boyd, C.A.; Farke, A.A.; Cruzado-Caballero, P.; Evans, D.C. (2021). "The phylogenetic nomenclature of ornithischian dinosaurs". PeerJ. 9: e12362. doi:10.7717/peerj.12362. PMC 8667728. PMID 34966571.

- ^ a b Brown, C. M.; Evans, D. C.; Ryan, M. J.; Russell, A. P. (2013). "New data on the diversity and abundance of small-bodied ornithopods (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) from the Belly River Group (Campanian) of Alberta". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 33 (3): 495–520. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.746229. S2CID 129160518.

- ^ a b Gilmore, C.W. (1915). "Osteology of Thescelosaurus, an orthopodous dinosaur from the Lance Formation of Wyoming". Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 49 (2127): 591–616. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.49-2127.591.

- ^ Zittel, K.A. von (1911). Grundzüge der Paläontologie (Paläzoologie) II. Abtielung Vertebrata (in German) (2 ed.). Berlin and München: Druck und verlad von R. Oldenbourg. p. 289.

- ^ Swinton, W.E. (1936). "Notes on the Osteology of Hypsilophodon, and on the Family Hypsilophodontidae". Journal of Zoology. 106 (2): 555–578. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1936.tb08518.x.

- ^ Sternberg, C.M. (1940). "Thescelosaurus edmontonensis, n. sp., and classification of the Hypsilophodontidae". Journal of Paleontology. 14 (5): 481–494. JSTOR 1298552.

- ^ Galton, P.M. (1972). "Classification and Evolution of Ornithopod Dinosaurs". Nature. 239 (5373): 464–466. Bibcode:1972Natur.239..464G. doi:10.1038/239464a0. S2CID 4196759.

- ^ Poole KE (2022). "Phylogeny of iguanodontian dinosaurs and the evolution of quadrupedality". Palaeontologia Electronica. 25 (3). 25.3.a30. doi:10.26879/702.

- ^ Longrich, Nicholas R.; Martill, David M.; Munt, Martin; Green, Mick; Penn, Mark; Smith, Shaun (2023-09-13). "Vectidromeus insularis, a new hypsilophodontid dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous Wessex Formation of the Isle of Wight, England". Cretaceous Research. 154: 105707. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2023.105707. S2CID 261933503.