Hydrothermal vent

| Marine habitats |

|---|

|

| Coastal habitats |

| Ocean surface |

| Open ocean |

| Sea floor |

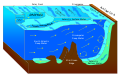

A hydrothermal vent is a fissure in a planet's surface from which geothermally heated water issues. Hydrothermal vents are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart, ocean basins, and hotspots. Hydrothermal vents exist because the earth is both geologically active and has large amounts of water on its surface and within its crust. Common land types include hot springs, fumaroles and geysers. The most famous hydrothermal vent system on land is probably within Yellowstone National Park in the United States. Under the sea, hydrothermal vents may form features called black smokers. Relative to the majority of the deep sea, the areas around submarine hydrothermal vents are biologically more productive, often hosting complex communities fueled by the chemicals dissolved in the vent fluids. Chemosynthetic archaea form the base of the food chain, supporting diverse organisms, including giant tube worms, clams, limpets and shrimp. Active hydrothermal vents are believed to exist on Jupiter's moon Europa, and ancient hydrothermal vents have been speculated to exist on Mars.[1]

Physical properties

Hydrothermal vents in the deep ocean typically form along the Mid-ocean ridges, such as the East Pacific Rise and the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. These are locations where two tectonic plates are diverging and new crust is being formed.

The water that issues from seafloor hydrothermal vents consists mostly of sea water drawn into the hydrothermal system close to the volcanic edifice through faults and porous sediments or volcanic strata, plus some magmatic water released by the upwelling magma. In terrestrial hydrothermal systems the majority of water circulated within the fumarole and geyser systems is meteoric water plus ground water that has percolated down into the thermal system from the surface, but it also commonly contains some portion of metamorphic water, magmatic water, and sedimentary formational brine that is released by the magma. The proportion of each varies from location to location.

In contrast to the approximately 2 °C ambient water temperature at these depths, water emerges from these vents at temperatures ranging from 60 °C up to as high as 464 °C.[2][3] Due to the high hydrostatic pressure at these depths, water may exist in either its liquid form or as a supercritical fluid at such temperatures. At a pressure of 218 atmospheres, the critical point of water is 375 °C. At a depth of 3,000 meters, the hydrostatic pressure of sea water is more than 300 atmospheres (as salt water is denser than fresh water). At this depth and pressure, seawater becomes supercritical at a temperature of 407 °C (see image). However the increase in salinity at this depth pushes the water closer to its critical point. Thus, water emerging from the hottest parts of some hydrothermal vents can be a supercritical fluid, possessing physical properties between those of a gas and those of a liquid.[2][3] Besides being superheated, the water is also extremely acidic, often having a pH value as low as 2.8 — approximately that of vinegar.

Sister Peak (Comfortless Cove Hydrothermal Field, 4°48′S 12°22′W / 4.800°S 12.367°W, elevation -2996 m), Shrimp Farm and Mephisto (Red Lion Hydrothermal Field, 4°48′S 12°23′W / 4.800°S 12.383°W, elevation -3047 m), are three hydrothermal vents of the black smoker category, located on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge near Ascension Island. They are presumed to have been active since an earthquake shook the region in 2002.[2][3] These vents have been observed to vent phase-separated, vapor-type fluids. In 2008, sustained exit temperatures of up to 407 °C were recorded at one of these vents, with a peak recorded temperature of up to 464 °C. These thermodynamic conditions exceed the critical point of seawater, and are the highest temperatures recorded to date from the seafloor. This is the first reported evidence for direct magmatic-hydrothermal interaction on a slow-spreading mid-ocean ridge.[2][3]

The initial stages of a vent chimney begin with the deposition of the mineral anhydrite. Sulfides of copper, iron and zinc then precipitate in the chimney gaps, making it less porous over the course of time. Vent growths on the order of 30 cm per day have been recorded.[4] An April 2007 exploration of the deep-sea vents off the coast of Fiji found those vents to be a significant source of dissolved iron.[5]

Black smokers and white smokers

Some hydrothermal vents form roughly cylindrical chimney structures. These form from minerals that are dissolved in the vent fluid. When the super-heated water contacts the near-freezing sea water, the minerals precipitate out to form particles which add to the height of the stacks. Some of these chimney structures can reach heights of 60 m.[6] An example of such a towering vent was "Godzilla", a structure in the Pacific Ocean near Oregon that rose to 40 m before it fell over.

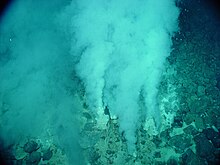

A black smoker or sea vent is a type of hydrothermal vent found on the seabed, typically in the abyssal and hadal zones. They appear as black chimney-like structures that emit a cloud of black material. The black smokers typically emit particles with high levels of sulfur-bearing minerals, or sulfides. Black smokers are formed in fields hundreds of meters wide when superheated water from below Earth's crust comes through the ocean floor. This water is rich in dissolved minerals from the crust, most notably sulfides. When it comes in contact with cold ocean water, many minerals precipitate, forming a black chimney-like structure around each vent. The metal sulfides that are deposited can become massive sulfide ore deposits in time.

Black smokers were first discovered in 1977 on the East Pacific Rise by scientists from Scripps Institution of Oceanography. They were observed using a deep submergence vehicle called Alvin belonging to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Now black smokers are known to exist in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, at an average depth of 2100 metres. The most northerly black smokers are a cluster of five named Loki's Castle,[7] discovered in 2008 by scientists from the University of Bergen at 73 degrees north, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between Greenland and Norway. These black smokers are of interest as they are in a more stable area of the Earth's crust, where tectonic forces are less and consequently fields of hydrothermal vents are less common.[8] The world's deepest black smokers are located in the Cayman Trough, 5,000 m (3.1 miles) below the ocean's surface.[9]

White smokers are vents that emit lighter-hued minerals, such as those containing barium, calcium, and silicon. These vents also tend to have lower temperature plumes. These alkaline hydrothermal vents also continuously generate acetyl thioesters, providing both the starting point for more complex organic molecules and the energy needed to produce them, Microscopic structures in such alkaline vents "show interconnected compartments that provide an ideal hatchery for the origin of life".[10]

Biological communities

Life has traditionally been seen as driven by energy from the sun, but deep sea organisms have no access to sunlight, so they must depend on nutrients found in the dusty chemical deposits and hydrothermal fluids in which they live. Previously, benthic oceanographers assumed that vent organisms were dependent on marine snow, as deep sea organisms are. This would leave them dependent on plant life and thus the sun. Some hydrothermal vent organisms do consume this "rain," but with only such a system, life forms would be very sparse. Compared to the surrounding sea floor, however, hydrothermal vent zones have a density of organisms 10,000 to 100,000 times greater.

Hydrothermal vent communities are able to sustain such vast amounts of life because vent organisms depend on chemosynthetic bacteria for food. The water that comes out of the hydrothermal vent is rich in dissolved minerals and supports a large population of chemo-autotrophic bacteria. These bacteria use sulfur compounds, particularly hydrogen sulfide, a chemical highly toxic to most known organisms, to produce organic material through the process of chemosynthesis.

The ecosystem so formed is reliant upon the continued existence of the hydrothermal vent field as the primary source of energy, which differs from most surface life on Earth which is based on solar energy. However, although it is often said that these communities exist independently of the sun, some of the organisms are actually dependent upon oxygen produced by photosynthetic organisms. Others are anaerobic as was the earliest life.

The chemosynthetic bacteria grow into a thick mat which attracts other organisms such as amphipods and copepods which graze upon the bacteria directly. Larger organisms such as snails, shrimp, crabs, tube worms, fish, and octopuses form a food chain of predator and prey relationships above the primary consumers. The main families of organisms found around seafloor vents are annelids, pogonophorans, gastropods, and crustaceans, with large bivalves, vestimentiferan worms, and "eyeless" shrimp making up the bulk of non-microbial organisms.

Tube worms form an important part of the community around a hydrothermal vent. The tube worms, like parasitic worms, absorb nutrients directly into their tissues. This is because tube worms have no mouth or even a digestive tract, so the bacteria live inside them. There are approximately 285 billion bacteria per ounce of tubeworm tissue. Tubeworms have red plumes which contain hemoglobin. Hemoglobin combines hydrogen sulfide and transfers it to the bacteria living inside the worm. In return the bacteria nourish the worm with carbon compounds. The two species that inhabit a hydrothermal vent are Tevnia jerichonana, and Riftia pachyptila. One community has been discovered dubbed 'Eel City', which consists predominantly of eels. Though eels are not uncommon, as mentioned earlier invertebrates typically dominate hydrothermal vents. Eel City is located near Nafanua volcanic cone, American Samoa.[11]

Other examples of the unique fauna who inhabit this ecosystem are scaly-foot gastropod Crysomallon squamiferum, a species of snail with a foot reinforced by scales made of iron and organic materials, and the Pompeii Worm Alvinella pompejana, which is capable of withstanding temperatures up to 80°C (176°F).

In 1993 there were already more than 100 gastropod species known to occur in hydrothermal vents.[12] Over 300 new species have been discovered at hydrothermal vents,[13] many of them "sister species" to others found in geographically separated vent areas. It has been proposed that before the North American plate overrode the mid-ocean ridge, there was a single biogeographic vent region found in the eastern Pacific.[14] The subsequent barrier to travel began the evolutionary divergence of species in different locations. The examples of convergent evolution seen between distinct hydrothermal vents is seen as major support for the theory of natural selection and of evolution as a whole.

Although life is very sparse at these depths, black smokers are the center of entire ecosystems. Sunlight is nonexistent, so many organisms — such as archaea and extremophiles — convert the heat, methane, and sulfur compounds provided by black smokers into energy through a process called chemosynthesis. More complex life forms like clams and tubeworms feed on these organisms. The organisms at the base of the food chain also deposit minerals into the base of the black smoker, therefore completing the life cycle.

A species of phototrophic bacterium has been found living near a black smoker off the coast of Mexico at a depth of 2,500 m (8,200 ft). No sunlight penetrates that far into the waters. Instead, the bacteria, part of the Chlorobiaceae family, use the faint glow from the black smoker for photosynthesis. This is the first organism discovered in nature to exclusively use a light other than sunlight for photosynthesis.[15]

New and unusual species are constantly being discovered in the neighborhood of black smokers. The Pompeii worm was found in the 1980s, and a scaly-foot gastropod in 2001 during an expedition to the Indian Ocean's Kairei hydrothermal vent field. The latter uses iron sulfides (pyrite and greigite) for the structure of its dermal sclerites (hardened body parts), instead of calcium carbonate. The extreme pressure of 2500 m of water (approximately 25 megapascals or 250 atmospheres) is thought to play a role in stabilizing iron sulfide for biological purposes. This armor plating probably serves as a defense against the venomous radula (teeth) of predatory snails in that community.

Biological theories

Although the discovery of hydrothermal vents is a relatively recent event in the history of science, the importance of this discovery has given rise to, and supported, new biological and bio-atmospheric theories.

The deep hot biosphere

At the beginning of his 1992 paper The Deep Hot Biosphere, Thomas Gold referred to ocean vents in support of his theory that the lower levels of the earth are rich in living biological material that finds its way to the surface.[16] Gold's theory however went beyond hydrothermal vents and proposed abiogenic petroleum origin (i.e. that petroleum is not just fossil based, but is manufactured deep in the earth), as further expanded in the book The Deep Hot Biosphere.[17] According to Gold: "Hydrocarbons are not biology reworked by geology (as the traditional view would hold) but rather geology reworked by biology." This hypothesis has been rejected by petroleum geologists, who hold that, even if this does occur, the amount of petrochemical produced in this manner is negligible; no naturally occurring abiotic petroleum has ever been found.[citation needed]

An article on abiogenic hydrocarbon production in the February 2008 issue of Science Magazine used data from experiments at Lost City (hydrothermal field) to report how the abiotic synthesis of hydrocarbons in nature may occur in the presence of ultramafic rocks, water, and moderate amounts of heat.[18]

Hydrothermal origin of life

Günter Wächtershäuser proposed the Iron-sulfur world theory and suggested that life might have originated at hydrothermal vents. Wächtershäuser proposed that an early form of metabolism predated genetics. By metabolism he meant a cycle of chemical reactions that produce energy in a form that can be harnessed by other processes.[19]

It has been proposed that amino-acid synthesis could have occurred deep in the Earth's crust and that these amino-acids were subsequently shot up along with hydrothermal fluids into cooler waters, where lower temperatures and the presence of clay minerals would have fostered the formation of peptides and protocells.[20] This is an attractive hypothesis because of the abundance of CH4 and NH3 present in hydrothermal vent regions, a condition that was not provided by the Earth's primitive atmosphere. A major limitation to this hypothesis is the lack of stability of organic molecules at high temperatures, but some have suggested that life would have originated outside of the zones of highest temperature. There are numerous species of extremophiles and other organisms currently living immediately around deep-sea vents, suggesting that this is indeed a possible scenario.

Exploration

In 1949, a deep water survey reported anomalously hot brines in the central portion of the Red Sea. Later work in the 1960s confirmed the presence of hot, 60°C (140°F), saline brines and associated metalliferous muds. The hot solutions were emanating from an active subseafloor rift. The highly saline character of the waters was not hospitable to living organisms.[21] The brines and associated muds are currently under investigation as a source of mineable precious and base metals.

The chemosynthetic ecosystem surrounding submarine hydrothermal vents were discovered along the Galapagos Rift, a spur of the East Pacific Rise, in 1977 by a group of marine geologists led by Jack Corliss of Oregon State University. In 1979, biologists returned to the rift and used ALVIN, an ONR research submersible from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, to see the hydrothermal vent communities with their own eyes. In that same year, Peter Lonsdale published the first scientific paper on hydrothermal vent life.[22]

In 2005, Neptune Resources NL, a mineral exploration company, applied for and was granted 35,000 km² of exploration rights over the Kermadec Arc in New Zealand's Exclusive Economic Zone to explore for seafloor massive sulfide deposits, a potential new source of lead-zinc-copper sulfides formed from modern hydrothermal vent fields. The discovery of a vent in the Pacific Ocean offshore of Costa Rica, named the Medusa hydrothermal vent field (after the serpent-haired Medusa of Greek mythology), was announced in April 2007.[23] The Ashadze hydrothermal field (13°N on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, elevation -4200 m) was the deepest known high-temperature hydrothermal field until 2010, when the Piccard site (18°33′N 81°43′W / 18.550°N 81.717°W, elevation -5000 m) was discovered by a group of scientists from NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. This site is located on the 110 km long, ultraslow spreading Mid-Cayman Rise.[24]

Exploitation

Hydrothermal vents, in some instances, have led to the formation of exploitable mineral resources via deposition of seafloor massive sulfide deposits. The Mount Isa orebody located in Queensland, Australia, is an excellent example.[25]

Recently, mineral exploration companies, driven by the elevated price activity in the base metals sector during the mid 2000s, have turned their attention to extraction of mineral resources from hydrothermal fields on the seafloor. Significant cost reductions are, in theory, possible.[26] Consider that in the case of the Mount Isa orebody, large amounts of capital are required to sink shafts and associated underground infrastructure, then laboriously drill and blast the ore, crush and process it, to win out the base metals, an activity which requires a large workforce.

The Marshall hydrothermal recovery system is a patented proposal to exploit hydrothermal vents for their energy and minerals. A hydrothermal field, consisting of chimneys and compacted chimney remains, can be reached from the surface via a dynamically positioned ship or platform, using conventional pipe, mined using modified soft rock mining technology (continuous miners), brought to the surface via the pipe, concentrated and dewatered then shipped directly to a smelter. While the concept sounds far-fetched, it uses already proven technology derived from the offshore oil and gas industries, and the soft-rock mining industries.

Two companies are currently engaged in the late stages of commencing to mine seafloor massive sulfides. Nautilus Minerals is in the advanced stages of commencing extraction from its Solwarra deposit, in the Bismarck Archipelago, and Neptune Minerals is at an earlier stage with its Rumble II West deposit, located on the Kermadec Arc, near the Kermadec Islands. Both companies are proposing using modified existing technology. Nautilus Minerals, in partnership with Placer Dome (now part of Barrick Gold), succeeded in 2006 in returning over 10 metric tons of mined SMS to the surface using modified drum cutters mounted on an ROV, a world first.[27] Neptune Minerals in 2007 succeeded in recovering SMS sediment samples using a modified oil industry suction pump mounted on an ROV, also a world first.[28]

Potential seafloor mining has environmental impacts including dust plumes from mining machinery affecting filter feeding organisms, collapsing or reopening vents, methane clathrate release, or even sub-oceanic land slides.[29] A large amount of work is currently being engaged in by both the above mentioned companies to ensure that potential environmental impacts of seafloor mining are well understood and control measures are implemented, before exploitation commences.[30]

Attempts have been made in the past to exploit minerals from the seafloor. The 1960s and 70s saw a great deal of activity (and expenditure) in the recovery of manganese nodules from the abyssal plains, with varying degrees of success. This does demonstrate however that recovery of minerals from the seafloor is possible, and has been possible for some time. Interestingly, mining of manganese nodules served as a cover story for the elaborate attempt by the CIA to raise the sunken Soviet submarine K-129, using the Glomar Explorer, a ship purpose built for the task by Howard Hughes. The operation was known as Project Jennifer, and the cover story of seafloor mining of manganese nodules may have served as the impetus to propel other companies to make the attempt.

Conservation

The conservation of Hydrothermal Vents has been the subject of sometimes heated discussion in the Oceanographic Community for the last 20 years.[31] It has been pointed out that it may be that those causing the most damage to these fairly rare habitats are scientists.[32][33] There have been attempts to forge agreements over the behaviour of scientists investigating vent sites but although there is an agreed code of practice there is as yet no formal international and legally binding agreement.[34]

Gallery

-

The pond of molten sulfur at Daikoku submarine volcano, Marianas Trench Marine National Monument, is about 15 feet long and 10 feet wide. The temperature of the molten sulfur was measured at 187°C (369°F).

-

A ledge on the side of a chimney in the Lost City vent field is topped with dendritic carbonate growths that form when mineral-rich vent fluids seep through the flange and come into contact with the cold seawater. Lost City vent field is located on Atlantis Massif, a prominent undersea massif, rising about 14,000 feet (4250 m) from the sea floor in the North Atlantic Ocean.

-

Zooarium chimney at Magic Mountain hydrothermal field, located on the Southern Explorer Ridge in the North Pacific Ocean, about 150 miles west of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada. The diffuse flow of Zooarium chimney provides an ideal habitat for vent biota.

-

A black smoker venting fluid at 312 degrees C at Magic Mountain hydrothermal field.

-

Sulfide chimney of the Magic Mountain hydrothermal field, British Columbia, Canada.

-

White smokers on the floor of Nikko caldera.

-

A zoomed-out view looking down on an advancing andesite lava flow (obscured by the plumes) at Northwest Rota volcano. The yellow parts of the plume contain molten droplets of sulfur; the white parts possibly other mineral particles (like alunite, an aluminum-bearing sulfate).

-

Giant smoky plume discovered pouring out of Brimstone Pit near the summit of Northwest Rota volcano.

-

An unplugged black smoker at a mid-ocean ridge hydrothermal vent in the Atlantic Ocean.

-

A black smoker known as The Brothers.

-

Siboglinidae Tube worms feeding at the base of a black smoker chimney.

See also

- Brine pool

- Cold seep

- Fumarole

- Geyser

- Hot springs

- Alvin submersible

- Lost City (hydrothermal field)

- Loki's Castle (hydrothermal field)

- Magic Mountain (hydrothermal field)

- Endeavour Hydrothermal Vents

- Origin of life

- Robert Ballard

References

- ^ Paine, Michael (15 May 2001) "Mars Explorers to Benefit from Australian Research" space.com

- ^ a b c d Haase, K. M.; et al. (13 November 2007). "Young volcanism and related hydrothermal activity at 5°S on the slow-spreading southern Mid-Atlantic Ridge". Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 8 (Q11002): 17. doi:10.1029/2006GC001509. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b c d Karsten M. Haase, Sven Petersen, Andrea Koschinsky, Richard Seifert, Colin W. Devey; et al. (2009). "Fluid compositions and mineralogy of precipitates from Mid Atlantic Ridge hydrothermal vents at 4°48'S". Publishing Network for Geoscientific & Environmental Data (PANGAEA). doi:10.1594/PANGAEA.727454. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); External link in|publisher= - ^ Tivey, Margaret K (1998-12-01). "How to Build a Black Smoker Chimney: The Formation of Mineral Deposits At Mid-Ocean Ridges". Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Retrieved 2006-07-07.

- ^ Chemical & Engineering News Vol. 86 No. 35, 1 Sept. 2008, "Tracking Ocean Iron", p. 62

- ^ Sid Perkins (2001). "New type of hydrothermal vent looms large". Science News. 160 (2). Society for Science: 21. doi:10.2307/4012715. JSTOR 4012715.

- ^ "Boiling Hot Water Found in Frigid Arctic Sea". livescience.com. 2008-07-24. Retrieved 2008-07-25.

- ^ "Scientists Break Record By Finding Northernmost Hydrothermal Vent Field". Science Daily. 2008-07-24. Retrieved 2008-07-25.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "World's deepest undersea vents discovered in Caribbean". BBC News. 2010-04-12. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ^ Lane, Nick (2010) "Life Ascending: the 10 great inventions of evolution" (Profile Books)

- ^ Astrobiology Magazine: Extremes of Eel City Retrieved 30 August 2007

- ^ Sysoev A. V. & Kantor Yu. I. (1995). "Two new species of Phymorhynchus (Gastropoda, Conoidea, Conidae) from the hydrothermal vents". Ruthenica 5: 17-26. abstract.

- ^ Botos, Sonia. "Life on a hydrothermal vent".

- ^ Van Dover, Cindy Lee. "Hot Topics: Biogeography of deep-sea hydrothermal vent faunas".

- ^ Beatty, JT; Overmann, J; Lince, MT; Manske, AK; Lang, AS; Blankenship, RE; Van Dover, CL; Martinson, TA; Plumley, FG (2005). "An obligately photosynthetic bacterial anaerobe from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent". PNAS. 102 (26): 9306–10. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503674102. PMC 1166624. PMID 15967984.

- ^ T. Gold: Proceedings of National Academy of Science http://www.pnas.org/cgi/reprint/89/13/6045

- ^ Thomas Gold, 1999, The Deep Hot Biosphere, Springer, ISBN 0387952535

- ^ Science Magazine, Abiogenic Hydrocarbon Production at Lost City Hydrothermal Field February 2008 http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/short/319/5863/604

- ^ G. Wächtershäuser: Proceedings of National Academy of Science http://www.pnas.org/cgi/reprint/87/1/200.pdf

- ^ Tunnicliffe, Verena (1991). "The Biology of Hydrothermal Vents: Ecology and Evolution". Oceanography and Marine Biology an Annual Review. 29: 319–408.

- ^ Degens, Egon T. (ed.), 1969, Hot Brines and Recent Heavy Metal Deposits in the Red Sea, 600 pp, Springer-Verlag

- ^ Lonsdale, P (1977). "Clustering of suspension-feeding macrobenthos near abyssal hydrothermal vents at oceanic spreading centers☆". Deep-Sea Res. 24 (9): 857–63. doi:10.1016/0146-6291(77)90478-7.

- ^ "New undersea vent suggests snake-headed mythology". April 18, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-18.

- ^ German, C. R.; Bowen, A.; et al. (August 10, 2010). "Diverse styles of submarine venting on the ultraslow spreading Mid-Cayman Rise" (PDF). PNAS. 107 (32): 14020–14025. doi:10.1073/pnas.1009205107. PMC 2922602. PMID 20660317. Retrieved December 31, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - ^ Perkins, WG (1984). "Mount Isa silica dolomite and copper orebodies; the result of a syntectonic hydrothermal alteration system". Economic Geology. 79 (4): 601. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.79.4.601.

- ^ http://www.theallineed.com/ecology/06030301.htm

- ^ Nautilus 2006 Press Release 03 http://www.nautilusminerals.com/s/Media-NewsReleases.asp?ReportID=138787&_Type=News-Releases&_Title=Nautilus-Outlines-High-Grade-Au-Cu-Seabed-Sulphide-Zone.

- ^ Kermadec Deposit http://www.neptuneminerals.com/Neptune-Minerals-Kermadec.html

- ^ Potential Deep Sea Mining in Papua New Guinea: a case study http://www.bren.ucsb.edu/research/documents/VentsThesis.pdf

- ^ RSC Article http://www.rsc.org/chemistryworld/issues/2007/january/treasuresdeep.asp

- ^ Devey, CW; Fisher, CR; Scott, S (2007). "Responsible Science at Hydrothermal Vents" (PDF). Oceanography. 20 (1): 162–72.

- ^ Johnson, Magnus (2005). "Oceans need protection from scientists too". Nature. 433 (7022): 105. doi:10.1038/433105a. PMID 15650716.

- ^ Johnson, Magnus (2005). "Deepsea vents should be world heritage sites". MPA News. 6: 10.

- ^ Tyler, Paul; German, Christopher; Tunnicliff, Verena (2005). "Biologists do not pose a threat to deep-sea vents". Nature. 434 (7029): 18. doi:10.1038/434018b. PMID 15744272.

Further reading

- Van Dover CL, Humphris SE, Fornari D, Cavanaugh CM, Collier R, Goffredi SK, Hashimoto J, Lilley MD, Reysenbach AL, Shank TM, Von Damm KL, Banta A, Gallant RM, Gotz D, Green D, Hall J, Harmer TL, Hurtado LA, Johnson P, McKiness ZP, Meredith C, Olson E, Pan IL, Turnipseed M, Won Y, Young CR 3rd, Vrijenhoek RC (2001). "Biogeography and ecological setting of Indian Ocean hydrothermal vents". Science. 294 (5543): 818–23. doi:10.1126/science.1064574. PMID 11557843.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Van Dover, Cindy Lee (2000). The Ecology of Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vents. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-04929-7.

- Beatty JT, Overmann J, Lince MT, Manske AK, Lang AS, Blankenship RE, Van Dover CL, Martinson TA, Plumley FG (2005). "An obligately photosynthetic bacterial anaerobe from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (26): 9306–10. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503674102. PMC 1166624. PMID 15967984.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Glyn Ford and Jonathan Simnett, Silver from the Sea, September/October 1982, Volume 33, Number 5, Saudi Aramco World Accessed 17 October 2005

- Ballard, Robert D., 2000, The Eternal Darkness, Princeton University Press.

- http://www.botos.com/marine/vents01.html#body_4

- Anaerobic respiration on tellurate and other metalloids in bacteria from hydrothermal vent fields in the eastern pacific ocean

- Andrea Koschinsky, Dieter Garbe-Schönberg, Sylvia Sander, Katja Schmidt, Hans-Hermann Gennerich and Harald Strauss (August 2008). "Hydrothermal venting at pressure-temperature conditions above the critical point of seawater, 5°S on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge". Geology. 36 (8): 615–618. doi:10.1130/G24726A.1. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Catherine Brahic (4 August 2008). "Found: The hottest water on Earth". New Scientist. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - Josh Hill (5 August 2008). "'Extreme Water' Found at Atlantic Ocean Abyss". The Daily Galaxy. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher=

External links

- Ocean Explorer (www.oceanexplorer.noaa.gov) - Public outreach site for explorations sponsored by the Office of Ocean Exploration.

- NOAA, Ocean Explorer Gallery, Submarine Ring of Fire 2006 Gallery, Submarine Ring of Fire 2004 Gallery - A rich collection of images, video, audio and podcast.

- NOAA, Ocean Explorer YouTube Channel

- Submarine Ring of Fire, Mariana Arc - Explore the volcanoes of the Mariana Arc, Submarine Ring of Fire.

- Hydrothermal Vent Systems Information from the Deep Ocean Exploration Institute, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

- Hydrothermal Vents Video From the Smithsonian Ocean Portal

- A new type of hydrothermal vent

- Vent geochemistry

- Everything you wanted to know about hydrothermal vents and the deep sea — Provided by New Scientist.

- a good overview of hydrothermal vent biology, published in 2006

- Images of Hydrothermal Vents in Indian Ocean- Released by National Science Foundation

- Neptune Minerals Ltd webpage - Exploring SMS deposits

- Nautilus Minerals Ltd webpage

- Ocean Explorer (www.oceanexplorer.noaa.gov) - Public outreach site for explorations sponsored by the Office of Ocean Exploration.

- NOAA, Ocean Explorer Gallery, Submarine Ring of Fire 2006 Gallery, Submarine Ring of Fire 2004 Gallery - A rich collection of images, video, audio and podcast.

- NOAA, Ocean Explorer YouTube Channel

- Submarine Ring of Fire, Mariana Arc - Explore the volcanoes of the Mariana Arc, Submarine Ring of Fire.

- Hydrothermal Vent Systems Information from the Deep Ocean Exploration Institute, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

- How to Build a Hydrothermal Vent Chimney

- Giant black smoker retrieved from abyss - a vent chimney retrieved by an Australian CSIRO Research Vessel north of Papua New Guinea in April–May 2000.

- Ancient Black Smoker - Parys Mountain, Anglesey