Hugh Denys

Hugh Denys (c. 1440 – 1511) of Osterley in Middlesex, was a courtier of Kings Henry VII and of the young Henry VIII. As Groom of the Stool to Henry VII, he was one of the King's closest courtiers, his role developing into one of administering the Privy Chamber, a department in control of the royal finances which during Denys's tenure of office also gained control over national fiscal policy. Denys was thus a vital player in facilitating the first Tudor king's controversial fiscal policies.

Early life

[edit]

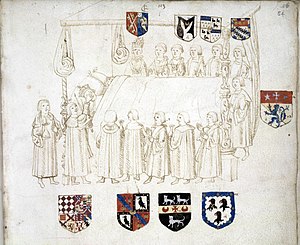

Denys was probably born at Olveston Court, Gloucestershire, c. 1440, the second son of Maurice Denys (d. 1466), Lord of the Manor of Alveston and Earthcott Green, Gloucestershire. His mother was Maurice's second wife, Alice Poyntz, daughter of Nicholas Poyntz of Iron Acton, Gloucestershire. The Denys family, formerly of Waterton, Bridgend in Coity Lordship, Glamorgan, had become established in Gloucestershire in 1380, on the marriage of Hugh's grandfather Sir Gilbert Denys (d. 1422) to Margaret Corbet, heiress of her brother William (d. 1377) to the Gloucestershire manors of Siston, Alveston, and Earthcott Green, together with the Hundred Court of Langley, as well as to Hope-juxta-Caus, Salop, and Lawrenny, Pembroke.[1] That Hugh was a second son is suggested by his use of a crescent as a mark of difference in his armorials.[2] The Heraldic Visitation of the Co. of Glos. of 1623, on the other hand, shows him as the third son.[3]

Marriage to Mary Ros

[edit]Denys married very advantageously to Mary Ros (or Roos), the daughter and only child of Richard Ros (1429–1492), younger son of Thomas de Ros, 8th Baron de Ros (1406–1430), of Hamlake Castle, Helmsley in North Yorkshire.[4] The latter had drowned in the River Seine while on campaign in France. Richard's mother was Eleanor Beauchamp (1407–1466), daughter of Richard de Beauchamp, 13th Earl of Warwick and Elizabeth Berkeley, daughter of Thomas, 5th Baron Berkeley. Mary's uncle Thomas de Ros, 9th Baron de Ros (1427–1464) of Hamlake married Philippa de Tiptoft, sister of John Tiptoft, 1st Earl of Worcester and Constable of England to King Edward IV. Thomas de Ros, Denys's uncle-in-law was an ardent Lancastrian and was attainted in 1461, and beheaded at Newcastle in 1464. Mary's aunt was Margaret de Ros who married firstly (c. 1452) William Lord Bottreux (d. 1462) of North Cadbury, Somerset. She married secondly in 1463 Sir Thomas Borough of Gainsborough, Lincolnshire. Because Margaret's mother Eleanor Beauchamp had married secondly Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset, Margaret's stepbrother became Henry Beaufort, 3rd Duke of Somerset, Captain of the King's Body Guard in about 1463. In 1464 he changed sides, again, back to the Lancastrians, and was beheaded at the Battle of Hexham in 1464. Margaret's second husband Sir Thomas Borough was on the victorious Yorkist side at Hexham so possibly witnessed the beheading of his wife's stepbrother.

Mary's cousin Eleanor Ros (1449–1487) married in 1469 Sir Robert Manners, Admiral of England who fought for Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth, from which marriage descended the Dukes of Rutland who inherited Belvoir Castle in Rutland from the De Ros family via Eleanor. Mary's cousin Edmund de Ros, heir of her beheaded uncle Thomas, was restored in his barony by Henry VII on his accession in 1485, and resided possibly quite close to the Denys's at Elsinges, Enfield, Middlesex.[5]

At Denys's death Mary had borne him no children, and Mary went on to marry her second husband Sir Giles Capel. One of Mary's books, a gift from Elizabeth of York and Lady Margaret Beaufort survives, the The Scale of Perfection by Walter Hilton, and she signed in it as "Mary Denys" and "Dame Capill".[6][7] Henry VII had given her a pension or annuity allocated from the manors of Cookham and Bray. In October 1535, Dame Mary Capel wrote to Thomas Cromwell, offering him £20 for a horse if he would secure her overdue payments from the annuity.[8]

Groom of the Stool to King Henry VII

[edit]

This office made its holder the King's closest courtier. The duties in the earliest days of this ancient post involved assisting the king in the performance in a decorous manner of his bodily function of excretion. Arrangements would have to be made for the custody of the stool itself (the word derives from Old English & Norse stul, signifying "chair", or piece of furniture for sitting on), provision of a suitable room for the use thereof, with curtains, hangings being provided. Washing equipment would also have been required: water, bowls, towel etc. Assistance would have been needed in undressing and re-dressing, bearing in mind the thick and valuable winter clothes worn by monarchs, replete with complex fastenings, which would need careful handling. Whether the function of the office involved intimate bodily cleaning must be questioned. The answer would seem to be affirmative. It is unlikely, as in the popular imagination, to have been a duty demanded by the king to boost his royal ego, rather a necessity to ensure the process was properly performed. Disposable paper tissue would only make its appearance several centuries later, cloth and water are likely to have been required. Clearly the office was one where the king would want to select a person in whose company he felt relaxed and comfortable. From this relationship grew the role of the Groom as a close adviser of the king. He had the king's ear, and this is likely to have given him power over the other courtiers, from their fear of his influence, and their desire to keep in his favour. By the reign of Henry VII, as exemplified in the person of Hugh Denys, the Groom of the Stool was a substantial man, from the gentry, married to an aristocratic wife, who died owning at least four manors (although possibly not all beneficially as will be discussed below). It is possible the role changed during Henry's reign, as Denys seems to have come into a lot of money late in life, as evidenced by the dates of purchase of his manors, and the funds may have come from perquisites or commissions retained from his various offices concerned with revenue collection, such as Gabler, Gauger and Ulnager. These latter are evidence as to how the role of Groom of the Stool changed into one of a financial function. Alternatively the manors may have been purchased in his name as investments beneficially owned by the royal privy purse.[citation needed]

The "Chamber System" of Royal Finance

[edit]The Tudor historian David Starkey describes this system, and Denys's role in it, as follows:

In 1493 Henry VII had broken with tradition and set up a new department of the Royal Household. Historically there were 2 of these, the Lord Steward's dept. which provided food and drink, and the Lord Chamberlain's which dealt with both ceremony and the King's personal service. To these Henry added a third: the secret or Privy Chamber. This took over responsibility for the King's body service. It was also used, as its name indicates, to enforce a much more rigorous separation between the King's public and private lives.

The establishment of the secret chamber greatly expanded the Groom's importance and his portfolio. Denys became the head officer of the new department. He controlled access to the King and assumed responsibility for the King's everyday necessities. Denys became the King's personal treasurer, running an account that later became known as the Privy Purse.

In the last few years of Henry's reign, avarice was made a policy and the result was a reign of terror. The means employed were through two financial instruments known as bonds and recognisances, which are agreements with penalty clauses for non-compliance. An individual was fined for offences real or imaginary, forced to pay part immediately, and to enter into bonds to pay the balance. He was therefore at the King's mercy. The arrangements were assessed and enforced by a sub-committee of the King's Council called the Council Learned in the Law, headed by Edmund Dudley, with Sir Richard Empson as a powerful member.

In the Autumn of 1508, Denys moved centre stage as the King recovered from a serious illness and decided on a wholesale extension of his policy of fiscal terrorism. Henry cast his net wider than just the elite, and created the post of Surveyor of the King's Prerogative, charged with the rigorous and universal enforcement of the King's rights as head of the feudal system. Local commissioners were appointed under Edward Belknap to enforce the policy on a county by county basis.

All the elements of an alternative system of taxation were in place - permanent, nation-wide and exempt from either parliamentary authority or scrutiny. The terms of Belknap's appointment are silent on what became of his profits, but it soon became clear they were to be paid over directly to Denys as a kind of private royal “slush fund.” Where they were paid is interesting: some at Greenwich Palace, but some at the private royal residences of Wanstead (of which Denys was the official keeper) and Hanworth. The last recording of such a paying-over of "fines assessed by the King's highness" was that paid by Belknap to Denys at Hanworth in February 1509, at which date the account book breaks off, incomplete[10]

It is clear that Denys re-invested these funds in real-estate as a bare trustee for the King, using a group of feoffees (persons to whom grants of freehold property are made), many of whom were close to the King. That is to say the King must have had absolute confidence in him that he would not misappropriate the funds, for as a bare trustee, no written agreement would have existed.

The existence of such a system, where the courtiers of the Privy Chamber started to control the national finances, was instrumental in the creation of the Tudor depotism.[11][12][13][14]

Hugh Denys a Citizen of London

[edit]Hugh Denys was a citizen of the City of London.[15] As a member of the Grocer's guild, he may possibly have been in commerce prior to his royal service.

Appointment as Verger of Windsor Castle

[edit]Hugh Denys held the post of Verger of Windsor Castle, as evidenced by the Letters & Papers of Henry VIII.[16] The sale documentation relating to Gray's Inn confirms this, referring to Denys as "Verger of Windsor Castle".[17] The duties of the office of Verger were to carry the "verge", or rod (from Latin virga, twig, rod) of office before a bishop, dean or other dignitary in ceremonies and processions[18] and most especially before the king at the annual Garter Ceremony.

Other Offices held by Hugh Denys

[edit]In the Pardon Roll of Henry VIII, of 16 March c. 1510, Hugh Denys is described as "Esquire of the Body, Gauger in Bristol, one of the Ushers at the Receipt of the Exchequer, Ulnager in Counties Oxford and Berks., Grocer and Garbler (sic) of London".[19] This implies that the by then elderly Denys, after his former royal master's death in 1509 had remained in royal service for Henry's son Henry VIII, but as a standard courtier, an Esquire of the Body. The reference to a Grocer implies membership of the Guild of Grocers in the City of London. It is therefore conceivable he may have had a career in commerce. The three offices of Gauger, Ulnager and Gabeler are all concerned with excise and duty collection, protection or measurement. An Ulnager inspected woolen cloth for quality, and assessed subsidy on it.[20] A Gabeler collected gabels, such as taxes, duty service charges or rent.[21] A Gauger measured or gauged bulk goods subject to duty, including alcoholic drink.[22] The connection to Bristol is possibly due to his roots at Olveston, Gloucestershire, only 9 miles (14 km) to the north. An Usher at the Receipt of the Exchequer was the official doorkeeper who allowed the Sheriffs from the various counties in, one by one, to the room in which was situated the chequered table around which sat the Lords of the Exchequer, to present their annual accounts for their county.[23] In these offices held by Denys is evidence of the evolution of the role of the Groom of the Stool from an officer dealing with palace finance to one dealing with taxation matters and national finance. It is likely these were substantive roles, not mere sinecures, in view of Denys's known day-to-day involvement with the royal finance in the "Chamber System".

Receives fines for the King's Silver

[edit]Fines for King's Silver (Common Pleas) were paid to Hugh Denys by order of the King and Council, 1505–1508. (Exchequer: Treasury of the receipt: Miscellaneous Books E 36/211)

Denys pays for a pair of virginals

[edit]Money is recorded having been paid by the Queen to Hugh Denys, reimbursing him for paying a deliveryman, or possibly their maker come in person, for a pair of clavichords, a form of early keyboard instrument capable of dynamics (i.e. playing loud and soft through striking the strings directly via a metal tangent), thought to be amongst the earliest imported into England.[24] The transaction is recorded in the Privy Purse expenses of Elizabeth of York, Queen of Henry VII, August 1502: "Item, the same day, Hugh Denys, for money by him delivered to a stranger (i.e. foreigner) that gave the Queen a payre of clavycordes. In crowns for his reward, iiii libres" (£4). The reward was four times greater than the estimated value of the gift, perhaps signifying the royal mark of approval and appreciation of the maker's generosity.[25] As Alison Weir wrote of Henry VIII "It was common for subjects to bring gifts to royalty in the expectation of a reward and such largesse or tipping was expected of a monarch".[26]

Coronation of the Queen, Katherine of Aragon, June 1509

[edit]Mary Denys was one of many to obtain a warrant for stuff for gowns, coats, etc., for particular persons, all courtiers and members of the Royal Household for the coronation of Henry VIII and Catherine. She is described as "Gentlewoman of the Queen's Chamber", appearing second in the list: Katerina Fortes, Mrs Denys, Mrs Butler, Mrs Weston, Mrs Jernyngham, Mrs Brewce, Mrs Stanhop, Mrs Odell. (A list of persons to receive a number of yards of scarlet and red cloth for the Coronation, among many hundred persons. Regarding the King's Chamber the Squires for the Body for the occasion are listed as: Hugh Denys, Richard Weston, John Porth (Keeper of the Books), Matthew Baker, Anthony Fetyplace, Thomas Apar, Sir John Carew. etc.[27]

Manors held by Hugh Denys, possibly on behalf of the Privy Purse

[edit]Towards the end of his life, and of the king's, when the Privy Chamber financial system was in operation, Hugh Denys purchased interests in several manors, in some possibly as a bare trustee for another beneficial owner. A bare trustee is someone who holds assets for the benefit of a third party purely on personal trust, no legal agreement or documentation existing. It is interesting to speculate who the beneficial owner might have been; one possibility is Henry VII himself. Denys does not seem to have been a rich man himself, being a second son he would have had no inheritance, and his wife was the daughter of a younger son too. Yet he purchased ostensibly in his own name for his own beneficial interest, some very substantial properties, via a large group of "feoffees" or trustees, especially those purchased from Lord Gray. One of the feoffees in the Shenley purchase was Edmund Dudley, who was the first president of the "Council Learned in the Law" set up by the king in the last years of his life, which David Starkey explains as a private slush fund for the king, reducing his need to consult Parliament in order to raise revenues.[28] The funds were generated by the imposition of "bonds" on those who were fined, often arbitrarily, for offences real or imaginary. Records exist which show these large sums were handed over regularly to Denys, the head of the Privy Chamber. Naturally the money needed investing somewhere, to generate income. A manor was then the closest equivalent to a stock exchange company. It was a going concern, with tenants, managers (i.e. stewards, bailiffs, etc.) and was fully staffed. The steward had only to redirect the stream of net profits to the new owner, as companies alter their dividend payments today to the bank accounts of new shareholders. Denys and his feoffees would receive the income directly into the Privy Purse, controlled by the head of the Privy Chamber, Denys himself, who, of course, was completely trusted by the king in handling his personal money. Thus, the king's revenue from extra-parliamentary fines was capitalised in real estate producing an income received directly by officers of the Privy Purse. It is significant that on Denys's death the properties held under this system of feoffees, in Denys's name, did not descend to Denys's heir, John Denys of Pucklechurch (as did apparently only Purleigh), but went to religious institutions with royal connections. This may have been the feoffees carrying out the secret wishes of the king, expressed to them verbally as his bare trustees. Such a system, based on trust alone, could clearly only function if staffed by the king's closest, most trusted aides. Hence the Groom of the Stool was the perfect candidate to control the operation, as a man of discretion, an intimate companion of the king, long in his confidence, probably without strong personal ambition,[29] therefore trustworthy.

Osterley Manor

[edit]Denys purchased the manor of Osterley, Middlesex some time after 1498, when it was recorded as belonging to Edward Cheeseman (d. 1510), the owner of Norwood manor.[30] It formerly belonged to John Somerset, physician to Henry VI and Chancellor of the Exchequer. On the death of John Somerset c. 1455, his estate in the manor, together with Wyke, covered nearly 500 acres (2.0 km2). He left his estate to feoffees for the support of the Chapel of All Angels at Brentford End which he founded.[31] Long after Denys's death, Syon Abbey leased Osterley to Robert Cheeseman in 1534.[32] It was later known as "The Chapel Lands" when granted in 1547 to the Duke of Somerset. "Osterley Farm", a part of the land, then comprised 202 acres (0.82 km2) with a farmhouse on the site of the present Osterley Park. By 1565, it was held by Sir Thomas Gresham, who consolidated it with other adjoining manors he owned. Hugh Denys's former manor became the site of the neo-classical Georgian mansion of Osterley Park, the parkland of which is still a pristine and undeveloped island within the suburbs of the Metropolis, being situated under the busy elevated section of the M4 Motorway approaching the Capital. The ancient Wyke Lane (now called Syon Lane) still exists, connecting Osterley with the former nunnery of Syon Abbey.

Wyke Manor

[edit]In 1444, Wyke manor belonged to John Somerset. It is likely that Denys acquired it at the same time as Osterley. After receiving Wyke from Denys's will, via Sheen Priory, Syon Abbey let it in 1537 on a 40-year lease.[33] In 1547, it was described as "Wyke Farm", comprising 104 acres (0.42 km2) of land and woods on each side of Wyke Lane (now Syon Lane).[34] By 1570, Wyke was held by Sir Thomas Gresham, together with Osterley.[35]

Purleigh Manor, Essex

[edit]Hugh Denys died seised of Purleigh Manor in Essex, 10 miles (16 km) E. of Chelmsford, which he bequeathed to his nephew, John Denys, of Pucklechurch, Gloucestershire. On the death in 1701 of Sir William Dennis (as the name later became), the last Dennis lord of the manor of Pucklechurch, it descended to his two daughters and co-heiresses, Mary, and her younger sister Elizabeth, who held it jointly until about 1736.[36] Elizabeth made an unfortunate marriage, as the second wife of a future notorious South-Sea Bubble bankrupt, Sir Alexander Cuming of Culter, in Aberdeen, 1st Baronet. His son by his first marriage was an extraordinary character, Sir Alexander Cuming, 2nd Baronet, whose mystical and powerful persona induced the Cherokee Indians to make him their Co-Emperor and to treat him as a living deity. He applied to King George III to formalise his title and give him funding, promising to win the Cherokees' loyalty against the French in the War of Independence, yet was rejected as an eccentric. He died in abject poverty, ejected from an almshouse in London. He still features prominently in Cherokee history.

Wallasea Island

[edit]This is situated directly south of Burnham-on-Crouch, Essex, 10 miles (16 km) south-east of Denys's manor of Purleigh.

Shenley Buckinghamshire

[edit]Purchase

These lands at Shenley (including seemingly Over-Shenley and Nether-Shenley) were quitclaimed on 10 May and 14 June 1506 by Edmund Grey and Florence (Lord de Gray of Gray's Inn) to Hugh Denys for £500, paid by Denys's feoffees. The record of this purchase is in the Feet of Fines (CP 25/1/22/129, no.103): Plea of Covenant re manor of Shenley & 20 messuages, 600 acres (2.4 km2) of land, 100 acres (0.40 km2) meadow, 600 acres (2.4 km2) pasture, 100 acres (0.40 km2) wood & 100s rent in Shenley and Eton and the advowson of the church of Shenley. Clearly this is a large transaction, coming just 2 or 3 months before Gray's further sale of Gray's Inn or Portpool Manor, Holborn, to Denys as well. It may, therefore, be a likely candidate as a capitalisation of royal "slush-fund" monies. It is useful to list the parties:

Querents: Sir Giles Daubeney (Chamberlain of the Lord King), Hugh Denys,esquire, Edmund Dudley,esquire, Thomas Wolverston, Thomas Pygot & Geogffrey Toppys

Deforciants: Edmund Lord Grey of Wilton and Florence his wife. They acknowledged the manor, tenements, and advowson "to be the right of Hugh as those which (his feoffees) have of their gift and have remised and quitclaimed them from themselves & the heirs of Florence to (the feoffees) and the heirs of Hugh forever. Warranty. (The feoffees) have given them (i.e. the Gray's) £500".

Disposal

A licence to alienate Verdons and Vaches and "lands in Shenley, Over-Shenley and Nether-Shenley" to the feoffees of Thomas Pygot (Robert Brudenell, Justice of the King's Bench, Ralph Verney, Thomas Pygot, senior, John Cheyne, Thomas Langston, Ralph Lane and Thomas Palmer) was granted to Denys and Thomas Wolverston by the king on 21 May 1509.[37]

Portpool Manor (Gray's Inn) Holborn

[edit]Hugh Denys, using the same system of enfeoffing others which had been common with the de Grays,[38] purchased Gray's Inn, formally known as Portpool Manor, from Edmund Grey, 9th Baron Grey de Wilton (d. 1511) on 12 August 1506. His 10 feoffees were as follows and included some of Henry VII's close financial officers and courtiers: Edward Dudley, Roger Lupton (Clerk, Provost of Eton College, Canon of Windsor, later Master in Chancery.), Godfrey Toppes, Edward Chamberlayn, William Stafford, John Ernley( who became Lord Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas in 1519), Thomas Pygot,(King's Serjeant in 1513), Richard Broke (a future judge of the Court of Common Pleas), William Tey, and Michael Fysher. The property consisted of 4 messuages, 4 gardens, the site of a windmill, 8 acres (32,000 m2) of land, 10 s. of rent and the advowson of Portpool Chantry.[39] Gray's Inn, now one of the Inns of Court, was then just starting to be tenanted by lawyers, as a centre of the legal profession. The list of feoffees clearly demonstrates that these persons were close to royal power; so, once again, it is possible that this transaction was an investment of Privy Purse funds.

Rushton, Eaton ("Ayton") and a moiety of the town of Tarporley, Cheshire

[edit]Denys's involvement with these manors is revealed by Returns to Writ of Certiorari (Nat.Archives Cheshire 7/10):

Hugh Denys, Edmund Dudley, Roger Lupton, John Ernley & Thomas Pygot

Versus:

Richard Grey, Earl of Kent, and Elizabeth, his wife.

Re: manors of Rushton, Ayton, and a moiety of the Town of Tarporley.

Pleas before the Justices of Chester returned into the Exchequer on a Writ of Certiorari. 1507-8

Corrodies held by Hugh Denys

[edit]A Corrody was an annual charge on its income, originally a voucher issued by a Priory to pay board and lodging of founders while visiting, later monetised and used by kings as transferable pensions. It therefore originally represented a life long living allowance of about 1 loaf and a gallon of ale per day.

Tywardreath Priory, Cornwall

[edit]Tywardreath Priory was situated 5 miles (8.0 km) E. of St Austell, only vestiges remain today. A receipt document is held by Cornwall Archives acknowledging receipt by Hugh Denys of 33s 4d from the Prior of Trewardaff being part payment of his corrody due on 25 March 1509.[40] On Denys's death the Corrody "in the King's gift by death of Hugh Denys" was granted by Henry VIII to another courtier, John Porth.[41] This Corrody had originally been monetised at 5 marks per annum, when granted by Henry VII in 1486 to his servant William Martyn, possibly Denys's predecessor.

Bury St. Edmunds Abbey

[edit]Hugh Denys also held a Corrody in Bury St. Edmunds Abbey, described as the "Monastery of St. Edmondsbury", as one was re-granted by Henry VIII on 4 January 1512, after Denys's death, to William Gower, Groom of the Chamber "vice Hugh Denys deceased". (i.e. in place of).[42]

Death and burial

[edit]Denys died on 9 October 1511 and was buried at Sheen Priory, next to his former royal master's Palace of Richmond, just 3 miles (4.8 km) SE and across the Thames from his manor of Osterley. His will was proved in the Court of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster. The graves and monuments at the priory were treated roughly after the Dissolution of the Monasteries, and certainly no trace of the grave remains.

Will of Hugh Denys

[edit]By his will, a long and complex document, Hugh Denys left the manors of Osterley, Wyke and Gray's Inn to Sheen Priory in trust for the augmentation of the Chapel of All Angels at Brentford End, founded by John Somerset, and for a hospital to be founded in connection with it.[43]

Text of Will of Hugh Denys

[edit]Extract: I will that all such persons as now have been feoffed to my use of and in my manors of Osterley, Wyke, Portepele(Portpool), called Greysynte(Gray's Inn), lands & tenements in the Co. of Middlesex, that they be of them seized to the use of me, my heirs and assigns unto such time as the Prior & Convent of the Charterhouse at Sheen in Co. Surrey have obtained of the King's grace sufficient licence for the amortisement (alienation?) of the aforesaid manors to have to their use and successors for ever.[44]

Delay of five years in effecting the bequest of Hugh Denys

[edit]The necessary royal licence to alienate (i.e. convey ownership in) the manors, listed in Denys's will for the bequest to Sheen, was not obtained by Denys's feoffees until 1516, five years after his death, after much legal wrangling between the Court and feoffees. It seems that one of the manors was found, seemingly Gray's Inn, during the legal process to grant a licence for alienation, technically to have escheated to the Crown previous apparently to Deny's ownership, by reason of "the death of Robert de Chiggewell without an heir". This effectively meant that Denys had never himself held good title, and his representatives were therefore legally incapable of dealing in the property concerned. The matter required regularisation, which was achieved. Denys had foreseen the delay experienced by his feoffees in receiving a licence to alienate, and had made in his will specific provisions for the disposition of the income generated pending the transfer to Sheen.

The Hospital or Chapel of All Angels

[edit]This Hospital stood beside Brentford Bridge, spanning the River Brent which flows from the north into the Thames east of Osterley. The exact site is not known. It had been founded by John Somerset, a previous owner of Osterley and Wyke manors, the King having laid the foundation stone.[45] Denys in his will entrusted his property to Sheen Priory to enlarge or perhaps refound it for seven poor men and to found a chantry for two secular priests. The foundation was to be called "The Chapel & Almshouses of Hugh Denys". The priests were to be resident and hold no other benefices, were to receive 9 marks a year and free fuel and were to pray for the souls of King Henry VII, John Somerset and Hugh Denys. The poor men, all resident, were to receive 7½d per week, free fuel and a gown worth 4 s.[46]

Double Alteration of Bequest of Hugh Denys

[edit]1530 Transfer of Bequest from Sheen Priory to Syon Abbey

[edit]

In 1530 for convenience of administration Sheen Priory transferred, under various covenants, the bequest of the manors of Osterley and Wyke received from Hugh Denys following his death in 1511, to Syon Abbey, a Bridgettine nunnery, its neighbour across the Thames one mile (1.6 km) due north. Gray's Inn was not similarly transferred, but remained held by Sheen. Purleigh although it had been left to John Denys, was subject to an annual charge payable to Sheen, as provided for in the will. It appears that Syon Abbey were attracted by the prospect of acquiring the two nearby manors, while distant Gray's Inn could serve no function in their plans. The charter effecting the transfer from Sheen to Syon is an elaborate illuminated manuscript "An Indenture, a book with indented covers is preserved in the Augmentation Office. It is a beautiful Illuminated MS on vellum with a neat drawing of St. Bridget in the initial letter". It recites Denys's will.[47] (Now in the British Library, Harleian MS 4640). The miniature on folio 1 shows the Virgin Mary kneeling before Christ's manger. A Transcript of the Indenture is printed in Aungier, History of Syon. (pp. 465–78) the abstract of which states:

- Indenture of Agreement between Roger Lupton[48] & others, executors to the will of Hugh Denys Esq. Agnes Jordan, Abbess of Syon Monastery & John Joborne Prior of the Carthusian Monastery of Sheen; relative to certain lands & tenements bequeathed by the same Hugh Denys to the last mentioned Priory, subject to certain payments for the purpose of augmenting the Chapel of All Angels near Syon.

1543 Establishment of the "Dennis Benefaction" at Magdalene College, Cambridge

[edit]On the Dissolution of Sheen Priory, the income from Purleigh provided by Denys's bequest required reassignment. The residuary legatee of his will was his nephew John Denys, third son of his elder brother Sir Walter Denys of Olveston Court. John's eldest brother was Sir William Denys of Dyrham Park who not only had inherited his father's lands, comprising the Corbet estates and those of the heiress Margaret Russell of Dyrham, second wife of Sir Gilbert Denys and matriarch of all the Denys's, Margaret Corbet not having produced a male heir, but he had also married very favorably Lady Ann Berkeley, daughter of Maurice, 3rd Baron Berkeley, de jure 2nd Marquis Berkeley, the leading family in Gloucestershire. It seems that Hugh wanted to help John, a mere younger son, to become established. John married Fortune Norton of nearby Bristol, and it seems they used their inheritance to purchase an estate in Pucklechurch, the manor between, and linking up, the established Denys manors of Siston and Dyrham. The Denys family had long held the farm of this manor from the Bishops of Bath and Wells. It was John's son Hugh Denys of Pucklechurch, perhaps named after his generous great uncle, who made application to Parliament to procure an Act which would effect a resettlement of the then defunct Sheen bequest onto Magdalene College, Cambridge, then being refounded(in 1542). The Act was obtained in 1543 under the abstract:

- An Act Concerning the Inheritance of Hugh Denys & £20 per annum to Magdalene College in Cambridge. 34 & 35 H VIII.[49]

The effect of the Act was to establish what became known as the "Dennis Benefaction". Of this endowment twenty nobles were to be used by the College and 20 marks were for the establishment of two fellowships, to be nominated by the King and called the "King's Fellows". These were the very first so-called bye fellowships. It was possibly the earliest benefaction received by the College, at the time one of the poorest of all the Cambridge colleges.[50] These were suppressed in 1861 and the Emoluments carried to the Scholarship Fund.[51] The "Dennis Benefaction" was thus founded, which is still extant today, within the consolidated "Scholarship Fund", a general fund for scholarships created by College Statute XX in 1956 by an Order in Council.[52] It is however a mere historical curiosity yielding only a peppercorn income due to over four centuries of inflation and poor investment decisions.

Part of the very lengthy text is as follows:[53]

- Hugh Denys (great nephew of HD (d. 1511)) most humbly beseecheth your most excellent Majesty your true faithful and obedient subject Hugh Denys son & heir of John Denys deceased nephew unto Hugh Denys also deceased some time one of the esquires of your Grace's Body. That whereas the said Hugh Denys deceased the 9th. day of the month of October in the year of our Lord God 1511, made and ordained and declared his last will in writing in default...all his manors lands and tenements with their...of his own issue to appurtenances and by the same his last will amongst "Dennis" in diverse other things & clauses therein contained willed tail upon that all and every such persons as then were seised (in)? to provide any manner of wise to his use of and in the manor of Purleigh masses with the appurtenances in the co. of Essex and of ever for the and reversion of the manor of Snorham Sayers souls of Southhouse Airesflete Marsh Lathenden...

Kinship to John Dennys the Angling poet

[edit]Hugh Denys of Pucklechurch chose Magdalene as the beneficiary of his reassigned inheritance from Hugh of Osterley, and it is quite likely that his son, the poet, John Dennys (d. 1609) was later himself a scholar at the College, and was either financed by it or accepted in gratitude of the bequest. John Dennys was clearly a highly educated man, who would find fame – 202 years after his death – as a poet, author of "The Secrets of Angling", a pastoral didactic poem, the first on angling in the English language. The work was published posthumously and anonymously as by "I.D. Esq", its true authorship being discovered in 1811 from an entry in the records of the Stationer's Company in London, dated 1613, in which his publisher had entered his name as John "Dennys", by which spelling he has become immortalized in the literary world. (The family name was generally spelled "Denys" until about 1600, as "Dennis" thereafter.) The poem is in imitation of Virgil's Georgics, and is replete with cryptic classical and biblical references designed to delight the educated Elizabethan reader. It is certain that John Dennys must have studied very deeply at a university somewhere and it is likely that it was at Magdalene, due to the family connection, that the author of "The Secrets of Angling" learned his art.

References

[edit]- ^ Visitation of Gloucestershire, p.51, Dennis

- ^ As shown in Sir Thomas Wriothesley's drawing of 1509, BL Add. MS 45131,f.54; John Gibbon in his Introductio ad Latinam Blasoniam, 1682, comments on the significance of marks of cadency distinguishing brothers: "At nota semper erit accrescens Luna secundi". (Moreover the waxing moon will always be the mark of the second).

- ^ The Visitation of the Co. of Glos. taken in the Year 1623 by Henry Chitty and John Phillipot as Deputies to William Camden, Clarenceux King of Arms. Ed. Sir J. Maclean, London, 1885. Denys ("Dennis") pedigree pp.49–53.

- ^ The Visitation of Gloucestershire, 1623. Dennis pedigree pp.49–53, in which Hugh Denys is described as "servant to K H 8, Harl.1041" the latter ms. containing the 1583 Visitation.

- ^ Collins's Peerage of England, vol.6

- ^ Barbara J. Harris, English Aristocratic Women, 1450–1550: Marriage and Family, Property and Careers (Oxford, 2002), p. 216.

- ^ Book inscribed by Mary, Dame Capel: YCBA

- ^ Joseph S. Block, "Political Corruption in Henrician England", Charles Carlton, State, Sovereigns & Society in Early Modern England (Stroud: Sutton, 1998), p. 50: James Gairdner, Letters and Papers, Henry VIII, 9 (London, 1886), p. 227 no. 671: The Statutes of the Realm, 3 (London, 1817), p. 15.

- ^ BL Add.MS 45131,f.54

- ^ This paragraph follows the text of Starkey, D. Henry: Virtuous Prince, London, 2008. Chapter 16, pp. 241–247.

- ^ Newton, Arthur Percival (July 1917). "The King's Chamber under the Early Tudors". The English Historical Review. 32 (127). Oxford University Press: 348.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ Dietz, Federick (September 1920). Bogart, Ernest; Fairlie, John; Lybyer, Albert (eds.). "English Government Finance 1485-1558". University of Illinois Studies in the Social Sciences. IX (3). Urbana: University of Illinois: 1.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ Richardson, Walter C. (1952). Tudor Chamber Administration 1485-1547 (First ed.). Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. 541.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ Starkey, David (2008). Henry: virtuous prince (First ed.). London: Harper Press. p. 400. ISBN 978-0007247714.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ Cokkburn, J.S. pp.204–212

- ^ Letters & Papers oh H VIII, vol.1,p.483

- ^ Ditchfield, P.H. Memorials of Old London. Vol.1, Holborn & the Inns of Court & Chancery.

- ^ Collins Dict. of the Eng.Lang. London, 1979

- ^ Letters & Papers, Foreign & Domestic, Henry VIII. Vol 1, 1509–1514. Pardon Roll, Part 4 (No.438, part 4)

- ^ LawyersandLaws.com, definitions

- ^ Gabeler: Dictionary of Old Occupations (www.familyresearcher.co.uk)

- ^ Gauger: Dictionary of Old Occupations.

- ^ Dialogue of the Exchequer (Dialogus Scaccario) gives a contemporary account of the workings of this process in the reign of Henry II. In Douglas, D. & Greenaway, G. (eds.) English Historical Documents 1142–1189. London, 1959. Vol 2, pp.490–572.

- ^ Musical Times 1/6/1893, p.331.

- ^ Brinsmead, Edgar. The History of the Pianoforte. 1876

- ^ Weir, Alison. Henry VIII King and Court. London, 2001. p.23.

- ^ Letters and Papers, Foreign & Domestic, Henry VIII, vol. 1 (London, 1920), 24/6/1509.

- ^ Starkey, David. Henry, Virtuous Prince. London, 2008. p.245. & chapter 16 in general.

- ^ Successful personal servants are generally characters willing to subsume their own ambitions to those of their masters'. Few memoirs of butlers to the rich and famous have ever been sold for money, perhaps the Burrell revelations about Princess Diana being a rare exception. In general the personality is one which receives satisfaction from not breaking trust.

- ^ VCH Middlesex, Vol 3, pp103–111; Cal. Close, 1485–1500, 334; Lysons, Environs of Lon.iii,320-1.

- ^ C 145/319,m.1; Cat, of Ancient Deeds,v,pp.507–8; Cal. Patent Rolls 1446–52, 29; Dictionary of National Biography vol.18, p.653.

- ^ SC 6/Hen VIII 6095; Middlesex digrees (Harl. Soc.65),47.

- ^ SC 6/Hen VIII 6090; Cal.Pat. 1555-7, 443–4.

- ^ Syon House MS. A.15,1.b.

- ^ C 66/1064

- ^ Essex Record Office D/DHn E21. 1709–1736 (1 bundle): Accounts for Purleigh Estate & rental & a/c's for the estate of Sir Alexander Cuming and Mrs Mary Dennis in Glos. & related correspondence.

- ^ L&P, F&D, H VIII, vol 1, (1920): Grants in May 1509.

- ^ Williams, E.1906.

- ^ Williams, E. Early Holborn, vol 1,pp.656–7; Williams, E. FRGS. Staple Inn: Customs House, Wool Court & Inn of Chancery: Its Mediaeval Surroundings & Associations. London, 1906.

- ^ "Receipt of payment of Corrody, Hugh Denys, esquire. Date: 26th. June, 1509" (Manuscript, 1 Piece: Cornwall Archives 146 ART/3/146)

- ^ Letters & Papers, For.& Dom. H VIII. Vol.1, (1920)

- ^ Letters & Papers For. & Dom. H VIII. Vol.1 (1920)

- ^ Victoria Co. History op.cit. fn 71: "Middlesex Record Office, Heston Incl.Award".

- ^ There is a partial recital of the will in Nat.Archives, E 211/291

- ^ Lysons, op.cit.

- ^ Cockburn J.S. (ed.) A History of the Co. of Middlesex, 1969. Vol.1, pp 204–212. Quotes: Syon House MS.A.15,5a (1608 Survey of Syon); Lysons, Environs of London. Vol.3, pp.91–92, 96; Aungier, Syon. pp.221–2,465–78.

- ^ Lysons, Daniel. The Environs of London, 1795. Vol.3, re Isleworth.

- ^ Roger Lupton was a cleric and fellow courtier of Denys's, Canon of Windsor (Denys was Verger) and Provost of Eton College, directly across the Thames from Windsor.

- ^ Parliament Office MSS III. Acts not on the Parliament Roll & not Printed in the Statutes at Large. 22 Jan. Parliament Roll, Chapter 42, Magdalene College, Cambridge.

- ^ Victoria County History, Cambridge. 1959, vol.3; Magdalene College, pp.450–6.

- ^ Shadwell, L. op.cit.

- ^ The Statutes of Magdalene College in the University of Cambridge. Cambridge, 1998. Appendix C, p.34.

- ^ From: Enactments in Parliament Specially Concerning the Universities of Oxford & Cambridge etc. Shadwell, Lionel L. (ed.) (4 vols.) Vol. 1 37 Ed III – 13 Ann, Oxford, 1912.