History of Kraków

Kraków is one of the largest and oldest cities in Poland, with the urban population of 804,237 (June, 2023).[1] Situated on the Vistula river (Polish: Wisła) in the Lesser Poland region, the city dates back to the 7th century.[2] It was the capital of Poland from 1038 to 1596, the capital of the Grand Duchy of Kraków from 1846 to 1918, and the capital of Kraków Voivodeship from the 14th century to 1999. It is now the capital of the Lesser Poland Voivodeship.

Historical affiliations

Vistulans, pre X century

Duchy of Bohemia, X century–c. 960

Duchy of Poland, c. 960–1025

Kingdom of Poland, 1025–1031

Duchy of Poland, 1031–1320

∟ Seniorate Province, 1138–1227

Duchy of Kraków, 1227–1320

Kingdom of Poland, 1320–1569

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, 1569–1795

Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, 1795–1804

Austrian Empire, 1804–1809

Duchy of Warsaw, 1809–1815

Free City of Cracow, 1815–1846

Austrian Empire, 1846–1867

Cisleithania, 1867–1918

Republic of Poland, 1918–1939

General Government, 1939–1945 (part of German-occupied Europe)

Provisional Government of National Unity, 1945–1947

Polish People's Republic, 1947–1989

Poland, 1989–present

Early history

[edit]

The earliest known settlement on the present site of Kraków was established on Wawel Hill, and dates back to the 4th century. Legend attributes the town's establishment to the mythical ruler Krakus, who built it above a cave occupied by a ravenous dragon, Smok Wawelski. Many knights unsuccessfully attempted to oust the dragon by force, but instead, Krakus fed it a poisoned lamb, which killed the dragon.[3] The city was free to flourish. Dragon bones, most likely that of mammoth,[4] are displayed at the entrance of the Wawel Cathedral.[5] Before the Polish state had been formed, Kraków was the capital of the tribe of Vistulans, subjugated for a short period by Great Moravia. After Great Moravia was destroyed by the Hungarians, Kraków became part of the kingdom of Bohemia. The first appearance of the city's name in historical records dates back to 966, when a Sephardi Jewish traveller, Abraham ben Jacob, described Kraków as a notable commercial centre under the rule of the then duke of Bohemia (Boleslaus I the Cruel). He also mentioned the baptism of Prince Mieszko I and his status as the first historical ruler of Poland.[2] Towards the end of his reign, Mieszko took Kraków from the Bohemians and incorporated it into the holdings of the Piast dynasty.

| Ethnic group | City proper | Kazimierz suburb |

Kleparz suburb |

Community |

| Poles | Circa 5,000 | Circa 1,500 | Circa 1,000 | 7,500 |

| Germans | Circa 3,500 | – | – | 3,500 |

| Jews | Circa 800 | – | – | 800 |

| Hungarians and/or Italians | Circa 200 | – | – | 200 |

| Others | Circa 500 | – | – | 500 |

| Subtotal (townsfolk) | 10,000 | 1,500 | 1,000 | 12,500 |

| Court, soldiery & clergy | Circa 2,500 | |||

| Grand total (population) | Circa 15,000 | |||

| Source: T. Ladenberger, Zaludnienie Polski na początku panowania Kazimierza Wielkiego, Lwów, 1930, p. 63 | ||||

By the end of the 10th century, the city was a leading center of trade.[7] Brick buildings were being constructed, including the Royal Wawel Castle with the Rotunda of Sts. Felix and Adauctus,[8] Romanesque churches, a cathedral, and a basilica. Sometime after 1042, Casimir I the Restorer made Kraków the seat of the Polish government. In 1079 on a hillock in nearby Skałka, the Bishop of Kraków, Saint Stanislaus of Szczepanów, was slain by the order of the Polish king Bolesław II the Generous. In 1138, the Testament of Bolesław III Wrymouth came into effect upon his death. It divided Poland into five provinces, with Kraków named as the Seniorate Province, meant to be ruled by the eldest male member of the royal family as the High Duke. Infighting among brothers, however, caused the seniorate system to soon collapse, and a century-long struggle between Bolesław's descendants followed. The fragmentation of Poland lasted until 1320.

Kraków was almost entirely destroyed during the first Mongol invasion of Poland in 1241, after the Polish attempt to repulse the invaders had been crushed in the Battle of Chmielnik. Kraków was rebuilt in 1257, in a form which was practically unaltered, and received self-government city rights from the king based on the Magdeburg Law, attracting mostly German-speaking burghers. In 1259, the city was again ravaged by the Mongols in the second Mongol invasion of Poland, 18 years after the first raid. A third attack, though unsuccessful, followed in 1287. The year 1311 saw the Rebellion of wójt Albert against Polish High Duke Władysław I. It involved the mostly German-speaking burghers of Kraków who, as a result, were massacred.[9] In the aftermath, Kraków's burgher class was gradually re-Polonized, and Polish burghers rose from a minority to a majority.[10]

Medieval Kraków was surrounded by a 1.9 mile (3 km) defensive wall complete with 46 towers and seven main entrances leading through them (see St. Florian's Gate and Kraków Barbican). The fortifications were erected over the course of two centuries.[11] The town defensive system appeared in Kraków after the city's location, i.e. in the second half of the 13th century (1257). This was when the construction of a uniform fortification line was commenced, but it seems the project could not be completed. Afterwards the walls, however, were extended and reinforced (a permit from Leszek Biały to encircle the city with high defensive walls was granted in 1285).[12]

In 1315 a large alliance of Poland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the duchies of Pomerania and Mecklenburg was formed in Kraków.[13]

Kraków rose to new prominence in 1364, when Casimir III of Poland founded the Cracow Academy, the second university in central Europe after the University of Prague. There had already been a cathedral school since 1150 functioning under the auspices of the city's bishop. The city continued to grow under the joint Lithuanian-Polish Jagiellon dynasty (1386–1572). As the capital of a powerful state, it became a flourishing center of science and the arts.

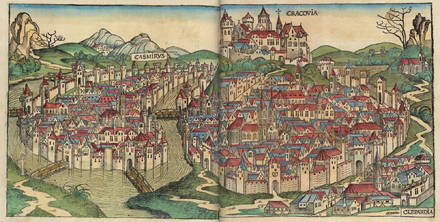

Kraków was a member of the Hanseatic League and many craftsmen settled there, established businesses and formed craftsmen's guilds. City Law, including guilds' depictions and descriptions, were recorded in the German language Balthasar Behem Codex. This codex is now featured at the Jagiellonian Library. By the end of the thirteenth century, Kraków had become a predominantly German city.[14] In 1475 delegates of the elector George the Rich of Bavaria came to Kraków to negotiate the marriage of Princess Jadwiga of Poland (Hedwig in German), the daughter of King Casimir IV Jagiellon to George the Rich. Jadwiga traveled for two months to Landshut in Bavaria, where an elaborate marriage celebration, the Landshut Wedding took place. Around 1502 Kraków was already featured in the works of Albrecht Dürer as well as in those of Hartmann Schedel (Nuremberg Chronicle) and Georg Braun (Civitates orbis terrarum).

During the 15th century extremist clergymen advocated violence towards the Jews, who in a gradual process lost their positions. In 1469 Jews were expelled from their old settlement to Spiglarska Street. In 1485 Jewish elders were forced into a renunciation of trade in Kraków, which led many Jews to leave for Kazimierz that did not fall under the restrictions due to its status as a royal town. Following the 1494 fire in Kraków, a wave of anti-Jewish attacks took place. In 1495, King John I Albert expelled the Jews from the city walls of Kraków; they moved to Kazimierz (now a district of Kraków).[15]

Renaissance

[edit]

The Renaissance, whose influence originated in Italy, arrived in Kraków in the late 15th century, along with numerous Italian artists including Francesco Fiorentino, Bartolommeo Berrecci, Santi Gucci, Mateo Gucci, Bernardo Morando, and Giovanni Baptista di Quadro. The period, which elevated the intellectual pursuits, produced many outstanding artists and scientists such as Nicolaus Copernicus who studied at the local Academy. In 1468 the Italian humanist Filip Callimachus came to Kraków, where he worked as the teacher of the children of Casimir IV Jagiellon. In 1488 the imperial Poet Laureate and humanist Conrad Celtes founded the Sodalitas Litterarum Vistulana ("Literary Society on the Vistula"), a learned society based on the Roman Academies. In 1489, sculptor Veit Stoss (Wit Stwosz) of Nuremberg finished his work on the high altar of St. Mary's Church. He later made a marble sarcophagus for his benefactor Casimir IV Jagiellon.[16] By 1500, Johann Haller had established a printing press in the city. Many works of the Renaissance movement were printed there during that time.

Art and architecture flourished under the watchful eye of King Sigismund I the Old, who ascended to the throne in 1507. He married Bona Sforza of a leading Milan family and using his new Italian connections began the major project (under Florentine architect Berrecci) of remaking the ancient residence of the Polish kings, the Wawel Castle, into a modern Renaissance palace.[17] In 1520, Hans Behem made the largest church bell, named the Sigismund Bell after King Sigismund I. At the same time Hans Dürer, younger brother of Albrecht Dürer, was Sigismund's court painter. Around 1511 Hans von Kulmbach painted a series of panels for the Church of the Pauline Fathers at Skałka and the Church of St. Mary.[18] Sigismund I also brought in Italian chefs who introduced Italian cuisine.[19]

In 1558, a permanent postal connection between Kraków and Venice, the capitals of the Kingdom of Poland and the Republic of Venice respectively, was established and Poczta Polska was founded.[20] In 1572, King Sigismund II died childless, and the throne passed briefly to Henry of Valois, then to Sigismund II's sister Anna Jagiellon and her husband Stephen Báthory, and then to Sigismund III of the Swedish House of Vasa. His reign changed Kraków dramatically, as he moved the government to Warsaw in 1596. A series of wars ensued between Sweden and Poland.[21]

The city was besieged and captured during the Swedish invasion in 1655. In December 1656, Kraków was occupied by the Transylvanian Prince George II Rákóczi, who was an ally of the Swedish king Charles X Gustav.[22]

After the partitions of Poland

[edit]

In the late 18th century, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was partitioned three times by its expansionist neighbors: Imperial Russia, the Austrian Empire, and the Kingdom of Prussia. After the first two partitions (1772 and 1793), Kraków was still part of the substantially reduced Polish nation. In 1794 Tadeusz Kościuszko initiated a revolt against the partitioning powers, the Kościuszko Uprising, in Kraków's market square. The Polish army, including many peasants, fought against the Russian and Prussian armies, but the larger forces ultimately put down the revolt. The Prussian army specifically took Kraków on 15 June 1794, and looted the Polish royal treasure kept at Wawel Castle. The stolen regalia, valued at 525,259 thalers, was secretly melted down in March 1809, while precious stones and pearls were appropriated in Berlin.[23] Poland was partitioned for the third time in 1795, and Kraków became part of the Austrian province of Galicia.

When Napoleon Bonaparte of the French Empire captured part of what had once been Poland, he established the Duchy of Warsaw (1807) as an independent but subordinate state. West Galicia, including Kraków, was taken from the Austrian Empire and added to the Duchy of Warsaw in 1809 by the Treaty of Schönbrunn, which ended the War of the Fifth Coalition. The Congress of Vienna (1815) restored the partition of Poland, but gave Kraków partial independence as the Free City of Cracow.

The city again became the focus of a struggle for national sovereignty in 1846, during the Kraków Uprising. The uprising failed to spread outside the city to other Polish lands, and was put down. This resulted in the annexation of the city state to the Austrian Empire as the Grand Duchy of Cracow,[24] once again part of the Galician lands of the empire.

In 1850 10% of the city was destroyed in the large fire.

After the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, Austria granted partial autonomy to Galicia,[25] making Polish a language of government and establishing a provincial Diet. As this form of Austrian rule was more benevolent than that exercised by Russia and Prussia, Kraków became a Polish national symbol and a center of culture and art, known frequently as the "Polish Athens" (Polskie Ateny) or "Polish Mecca" to which Poles would flock to revere the symbols and monuments of Kraków's (and Poland's) great past.[26] Several important commemorations took place in Kraków during the period from 1866 to 1914, including the 500th Anniversary of the Battle of Grunwald in 1910,[27] in which world-renowned pianist Ignacy Paderewski unveiled a monument. Famous painters, poets and writers of this period, living and working in the city include Jan Matejko, Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Jan Kasprowicz, Juliusz Kossak, Wojciech Kossak, Stanisław Wyspiański and Stanisław Przybyszewski. The latter two were leaders of Polish modernism.

The Fin de siècle Kraków, even under the partitions, was famously the center of Polish national revival and culture, but the city was also becoming a modern metropolis during this period. In 1901 the city installed running water and witnessed the introduction of its first electric streetcars. (Warsaw's first electric streetcars came in 1907.) The most significant political and economic development of the first decade of the 20th century in Kraków was the creation of Greater Kraków (Wielki Kraków), the incorporation of the surrounding suburban communities into a single administrative unit. The incorporation was overseen by Juliusz Leo, the city's energetic mayor from 1904 to his death in 1918 (see also: the Mayors of Kraków).

Thanks to migration from the countryside and the fruits of incorporation from 1910 to 1915, Kraków's population doubled in just fifteen years, from approx. 91,000 to 183,000 in 1915. Russian troops besieged Kraków during the first winter of the First World War, and thousands of residents left the city for Moravia and other safer locales, generally returning in the spring and summer of 1915. During the war Polish Legions led by Józef Piłsudski set out to fight for the liberation of Poland, in alliance with Austrian and German troops. With the fall of Austro-Hungarian Empire, Poles liberated the city and it was included with the newly reborn Polish state (1918). Between the two World Wars Kraków was also a major Jewish cultural and religious center (see: Synagogues of Kraków), with the Zionist movement relatively strong among the city's Jewish population.

World War II

[edit]

Poland was partitioned again at the onset of the Second World War. The Nazi German forces entered Kraków on September 6, 1939. The residents of the city were saved from German attack by the courageous Mayor Stanisław Klimecki who went to meet the invading Wehrmacht troops. He approached them with the call to stop shooting because the city was defenseless: "Feuer einstellen!" and offered himself as a hostage. He was killed by the Gestapo three years later in the Niepołomice Forest.[28] The German Einsatzgruppen I and zbV entered the city to commit atrocities against Poles.[29] On September 12, the Germans carried out a massacre of 10 Jews.[30] On November 4, Kraków became the capital of the General Government, a colonial authority under the leadership of Hans Frank.[31] The occupation took a heavy toll, particularly on the city's cultural heritage. On November 6, during the infamous Sonderaktion Krakau 184 professors and academics of the Jagiellonian University (including Rector Tadeusz Lehr-Spławiński among others) were arrested at the Collegium Novum during a meeting ordered by the Gestapo chief SS-Obersturmbannführer Bruno Müller. President of Kraków, Klimecki was apprehended at his home the same evening. After two weeks, they were sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp, and in March 1940 further to Dachau.[32][33] Those who survived were released only after international protest involving the Vatican.[34] On November 9–10, during the Intelligenzaktion, the Germans carried out further mass arrests of 120 Poles, including teachers, students and judges.[35] The Sicherheitspolizei took over the Montelupich Prison, which became one of the most infamous in German-occupied Poland. Many Poles arrested in Kraków, and various other places in the region, and even more distant cities such as Rzeszów and Przemyśl, were imprisoned there.[36] Over 1,700 Polish prisoners were eventually massacred at Fort 49 of the Kraków Fortress and its adjacent forest, and deportations of Polish prisoners to concentration camps, incl. Ravensbrück and Auschwitz, were also carried out.[37] The prison also contained a cell for kidnapped Polish children under the age of 10, with an average capacity of about 70 children, who were then sent to concentration camps and executed.[38] From September to December 1939, the occupiers also operated a Dulag transit camp for Polish prisoners of war.[39]

Many relics and monuments of national culture were looted and destroyed (yet again), including the bronze statue of Adam Mickiewicz stolen for scrap. The Jewish population was first ghettoized, and later murdered. Two major concentration camps near Kraków included Płaszów and the extermination camp of Auschwitz, to which many local Poles and Polish Jews were sent. Specific events surrounding the Jewish ghetto in Kraków and the nearby concentration camps were famously portrayed in the film Schindler's List, itself based on a book by Thomas Keneally entitled Schindler's Ark.[40][41] The Polish Red Cross was also aware of over 2,000 Polish Jews from Kraków, who escaped from the Germans to Soviet-occupied eastern Poland, and then were deported by the Soviets to the USSR.[42]

The Polish resistance movement was active in the city. Already in September 1939, the Organizacja Orła Białego resistance organization was founded.[43] Kraków became the seat of one of the six main commands of the Union of Armed Struggle in occupied Poland (alongside Warsaw, Poznań, Toruń, Białystok and Lwów).[44] A local branch of the Żegota underground Polish resistance organization was established to rescue Jews from the Holocaust.[45]

The Germans operated several forced labour camps in the city, and in 1942–1944, they also operated the Stalag 369 prisoner-of-war camp for Dutch, Belgian and French POWs. In 1944, during and following the Warsaw Uprising, the Germans deported many captured Poles frow Warsaw to Kraków.[46]

A common account popularized in the Soviet-controlled communist People's Republic of Poland, held that due to a rapid advance of the Soviet armies, Kraków allegedly escaped planned destruction during the German withdrawal.[47] There are several different versions of that account.[48][49][50] According to a version based on self-written Soviet statements,[51] Marshal Ivan Konev claimed to have been informed by the Polish patriots of the German plan,[49] and took an effort to preserve Kraków from destruction by ordering a lightning attack on the city while deliberately not cutting the Germans from the only withdrawal path, and by not aiding the attack with aviation and artillery.[52] The credibility of those accounts has been questioned by Polish historian Andrzej Chwalba who finds no physical evidence of the German master plan for demolition and no written proof showing that Konev ordered the attack with the intention of preserving the city. He portrays Konev's strategy as ordinary – only accidentally resulting in little damage to Kraków – exaggerated later into a myth of "Konev, savior of Kraków" by Soviet propaganda. The Red Army entry into the city was accompanied by a wave of rapes of women and girls resulting in official protests.[53][54]

Post-war period

[edit]After the war, the government of the People's Republic of Poland ordered the construction of the country's largest steel mill in the suburb of Nowa Huta. This was regarded by some as an attempt to diminish the influence of Kraków's intellectual and artistic heritage by industrialization of the city and by attracting to it the new working class. In the 1950s some Greeks, refugees of the Greek Civil War, settled in Nowa Huta.[55]

The city is regarded by many to be the cultural capital of Poland. In 1978, UNESCO placed Kraków on the list of World Heritage Sites. In the same year, on October 16, 1978, Kraków's archbishop, Karol Wojtyła, was elevated to the papacy as John Paul II, the first non-Italian pope in 455 years.

Kraków's population has quadrupled since the end of World War II. After the collapse of the Soviet Empire and the subsequent joining of the European Union, Offshoring of IT work from other nations has become important to the economy of Kraków and Poland in general in recent years. The city is the key center for this kind of business activity. There are about 20 large multinational companies in Kraków, including centers serving IBM, General Electric, Motorola, and Sabre Holdings, along with British and German-based firms.[56][57]

On May 29, 1990 following the end of communism in Poland, the director of the Personnel Office of the Office of the Council of Ministers handed over a nomination act temporarily appointing Tadeusz Piekarz as the Voivode of Kraków, which was formally confirmed a month later, on June 28, 1990. On the day of the announcement nomination at the Kraków City Hall, there was a symbolic handover of the keys to the city by the outgoing president and voivode Jerzy Rościszewski which included a protocol on the transfer of functions between the outgoing Voivode and the newly appointed Voivode of Kraków acting as the Mayor of Kraków. This act referred to the legal basis for the operation of the Kraków City Hall and the Voivodeship Office in Krakow.[58]

In recent history, Kraków has co-hosted various international sports competitions, including the 2016 European Men's Handball Championship, 2017 Men's European Volleyball Championship, 2021 Men's European Volleyball Championship, 2023 World Men's Handball Championship and 2023 European Games.[59]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Wyniki badań bieżących - Baza Demografia - Główny Urząd Statystyczny". demografia.stat.gov.pl. Retrieved 2024-02-25.

- ^ a b The Municipality Of Kraków Press Office, 1996–2007, in participation with ACK Cyfronet of the AGH University of Science and Technology, "Our City. History of Krakow, archaeological findings". Archived from the original on 2007-02-19. Retrieved 2007-09-11.

- ^ ""The Legend of Smok Wawelski" (the Dragon of Wawel) at www.kresy.co.uk". Archived from the original on 2009-06-17. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- ^ "The History of Wawel Castle and Cathedral" with works cited, at www.valsworld.org Archived 2011-07-28 at the Wayback Machine (PDF)

- ^ Wawel Royal Castle, homepage. Maria Dębicka, "The Dragon's Den". Archived from the original on 2007-04-22. Retrieved 2007-09-11.

- ^ Francis W. Carter (1994). Trade and urban development in Poland: an economic geography of Cracow. Cambridge University Press. p. 71. ISBN 0-521-41239-0. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Krystyna Van Dongen (née Wyskwarska) and Frank Van Dongen, "The royal castle". Archived from the original on 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2007-05-12.

- ^ Stanisław Rosik and Przemysław Urbańczyk, Poland – Ecclesiastical organization

- ^ Nora Berend (2017). The Expansion of Central Europe in the Middle Ages. Routledge.

- ^ Robert Bartlett (2003). The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization and Cultural Change 950 - 1350. Penguin UK.

- ^ Andrew Beattie, Landmark Publishing, Tim Pepper, Stare Miasto, the Old Town, Krakow Published by Hunter Publishing

- ^ Marek Żukow-Karczewski, "The Barbican", Kraków Magazyn Kulturalny (Special Edition), Kraków, 1991, p. 58-59.

- ^ "Wydarzenia z kalendarza historycznego: 27 czerwca 1315". chronologia.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ Zamoyski, Adam (2015). Poland. A History. William Collins. p. 26. ISBN 978-0007556212.

- ^ The Torah Ark in Renaissance Poland: A Jewish Revival of Classical Antiquity, Ilia M. Rodov, Brill, pages 2–6

- ^ Marek Strzala. "Important Dates in Krakow's History: Veit Stoss altarpiece for Krakow's Basilica of Virgin Mary". Retrieved 12 May 2007.

- ^ Michael J. Mikoś, Polish Renaissance Literature: An Anthology. Cultural Background. Ed. Michael J. Mikoś. Columbus, Ohio/Bloomington, Indiana: Slavica Publishers. 1995. ISBN 978-0-89357-257-0

- ^ Haldane Macfall, A History of Painting Published by Kessinger Publishing. Page 113.

- ^ Kenneth F. Lewalski, "Sigismund I of Poland: Renaissance King and Patron", Studies in the Renaissance, (1967) 14#1 pp. 49–72 online at JSTOR

- ^ "Dzień Łącznościowca". Muzeum Poczty i Telekomunikacji we Wrocławiu (in Polish). 18 October 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ^ "Poland – The Commonwealth | history – geography". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-03-16.

- ^ Milewski, Dariusz (8 June 2007). "Szwedzi w Krakowie". Internet Archive (in Polish). Mówią Wieki. Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ^ Monika Kuhnke. "Rabunek od czasów zaborów do II wojny światowej (The plunder during the Partitions and until World War II)". www.zabytki.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2020-11-22. Retrieved 2010-10-30.

- ^ The Encyclopedia Americana 1972- Volume 16 - Page 537 By the provisions of the Congress of Vienna (1815) it became the Republic of Krakow, a protectorate of Russia, Prussia, and Austria, but in 1846 it reverted to Austria as the Grand Duchy of Krakow."

- ^ Marek Strzala, "History of Krakow" "(see: Franz Joseph I granted Krakow the municipal government)". Retrieved 2007-05-12.

- ^ Bożena Szara (6 April 2001). "Między dwoma światami czyli powrót do przeszłości" [Between the two worlds, or a return to the past] (in Polish). Przegląd Polski. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved October 14, 2012. Search key: "polskie Ateny".

- ^ Hubert Zawadzki, Jerzy Lukowski, A Concise History of Poland, Cambridge University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-521-55917-0, Google Print, p.148

- ^ "Stanisław Klimecki (11.9.1939 arrest – 16.12.1942 execution)". Archiwum ofiar terroru nazistowskiego i komunistycznego w Krakowie. Muzeum Historyczne Miasta Krakowa. 1939–1956. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ Wardzyńska, Maria (2009). Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion (in Polish). Warszawa: IPN. pp. 58–59.

- ^ Wardzyńska, p. 124

- ^ Mordecai Paldiel, The Path of the Righteous: Gentile Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust, KTAV Publishing House, 1993, pg. 177. ISBN 0-88125-376-6

- ^ Mirosław Sikora (2008). "Zasady i praktyka przejęcia majątku polskiego przez III Rzeszę (Theory and practise of Poland's takeover by the Third Reich)" (PDF direct download: 1.64 MB). Bulletin PAMIĘĆ I SPRAWIEDLIWOŚĆ, No. 2 (13). Institute of National Remembrance, Poland. pp. 404 (66, and 84). Retrieved May 8, 2012.[permanent dead link] Note: Please save a copy to your own hard drive without opening it, and run a virus check through that copy first if you're concerned with security. Source is reliable.

- ^ Franciszek Wasyl (November 1, 2011). "Krakowski etap "Sonderaktion Krakau". Wspomnienie Zygmunta Starachowicza" (in Polish). WordPress.com. Archived from the original on June 20, 2010. Retrieved May 8, 2012.

- ^ "Więźniowie Sonderaktion Krakau" (PDF). Alma Mater No. 118. Jagiellonian University. Archived from the original (PDF 275 KB) on December 24, 2013. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ Wardzyńska, p. 256

- ^ Wardzyńska, p. 257–258

- ^ Wardzyńska, pp. 256, 261, 268–269

- ^ Kostkiewicz, Janina (2020). "Niemiecka polityka eksterminacji i germanizacji polskich dzieci w czasie II wojny światowej". In Kostkiewicz, Janina (ed.). Zbrodnia bez kary... Eksterminacja i cierpienie polskich dzieci pod okupacją niemiecką (1939–1945) (in Polish). Kraków: Uniwersytet Jagielloński, Biblioteka Jagiellońska. p. 55.

- ^ "German Dulag Camps". Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ^ Jews in Krakow Archived 2013-06-23 at the Wayback Machine (Encyclopaedia Judaica)

- ^ Holocaust in Krakow Archived 2013-06-23 at the Wayback Machine (Encyclopaedia Judaica)

- ^ Boćkowski, Daniel (1999). Czas nadziei. Obywatele Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej w ZSRR i opieka nad nimi placówek polskich w latach 1940–1943 (in Polish). Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Neriton, Instytut Historii Polskiej Akademii Nauk. p. 173. ISBN 83-86842-52-0.

- ^ Płuta-Czachowski, Kazimierz (1987). Organizacja Orła Białego (in Polish). Warszawa: PAX. pp. 76–77.

- ^ Grabowski, Waldemar (2011). "Armia Krajowa". Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej (in Polish). No. 8-9 (129-130). IPN. p. 116. ISSN 1641-9561.

- ^ Datner, Szymon (1968). Las sprawiedliwych (in Polish). Warszawa: Książka i Wiedza. p. 69.

- ^ "Transporty z obozu Dulag 121". Muzeum Dulag 121 (in Polish). Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ^ Anna M. Cienciala, "The German Occupation of Poland and the Holocaust in German-occupied Poland." Chapter: "The Polish Resistance Movement against the Germans." The Polish Review, v.48, 1, 2003, 49–72.[1]

- ^ Norman Salsitz, Stanley Kaish, Salsitz, Norman; Kaish, Stanley (2002-12-01). Three Homelands: Memories of a Jewish Life in Poland, Israel, and America. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0734-2. Retrieved 2007-11-22. According to authors the Jewish-Polish secretary of the German M&K Construction Company, Amalie Petranker (hiding from the Nazis as Felicja Milaszewska), came into the possession of a set of plans that showed where explosives had been planted with the intention of destroying the city. The plans were found as soon as the German managers had fled Kraków. Notably, Petranker continued to live in the apartment previously occupied by the managers of M&K Construction on Juljusza Lea Street until receiving the government notice to vacate.

- ^ a b "The Germans planned to blow up Krakow, which has many medieval buildings and museums, but they were foiled when the map of mines and explosives placed around the city, was delivered by a couple of Polish citizens to the Russians, who were closing in on the city."

Anna M. Cienciala, "The German Occupation of Poland and the Holocaust in German-occupied Poland." Chapter: "The Polish Resistance Movement against the Germans." The Polish Review, v.48, 1, 2003, 49–72. - ^ (in Polish) Leszek Mazan, Ocalenie Krakowa, Polityka – nr 3 (2487) z dnia 22-01-2005. According to this article, Konev was ordered to save Kraków by Stalin, who was pressured by Roosevelt, who was in turn pressured by Vatican (acting on the requests of Polish clergy).

- ^ Ivan Katyshkin, "Sluzhili my v shtabe armeiskom", Moskva, Voenizdat, 1979, LCCN 80-503360, p. 155

- ^ Makhmut Gareev, Marshal Konev Archived 2007-10-13 at the Wayback Machine, Krasnaia Zvezda, April 12, 2001

- ^ (in Polish) Alma Mater, Jagiellonian University monthly, No.64 (2004). Interview with professor Andrzej Chwalba, by Rita Pagacz-Moczarska. "OKUPOWANY KRAKÓW". Archived from the original on 2008-05-24. Retrieved 2007-09-11.

- ^ (in Polish) Andrzej Chwalba. Kraków w latach 1939–1945 Archived 2007-12-03 at the Wayback Machine (Cracow under German Occupation, 1939–1945). Dzieje Krakowa, volume 5. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2002.

- ^ Kubasiewicz, Izabela (2013). "Emigranci z Grecji w Polsce Ludowej. Wybrane aspekty z życia mniejszości". In Dworaczek, Kamil; Kamiński, Łukasz (eds.). Letnia Szkoła Historii Najnowszej 2012. Referaty (in Polish). Warszawa: IPN. p. 118.

- ^ Wide Angle: The Future of Outsourcing. (Section: Poland) Educational Broadcasting Corporation. Accessed 16 March 2011.

- ^ The Sabre Holings office at Krakow, Poland. Archived May 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Accessed 16 March 2011.

- ^ Pawel Gofron. Relacje wojewodów krakowskich z samorządem miasta Krakowa w latach 1990-1998 (in Polish). Uniwersytet Papieski Jana Pawła II w Krakowie. p. 44.

- ^ "Key facts & figures: European Games Kraków-Malopolska 2023". european-games.org. 19 June 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Laurențiu Rădvan [in Romanian] (January 2010), "Towns in the Kingdom of Poland: Wroclaw and Krakow", At Europe's Borders: Medieval Towns in the Romanian Principalities, Translated by Valentin Cîrdei, Leiden: Brill (published 2010), p. 47+, ISBN 9789004180109

External links

[edit]- Europeana. Items related to Kraków, various dates.