Historical method

| Part of a series on |

| History |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Research |

|---|

|

| Philosophy portal |

Historical method is the collection of techniques and guidelines that historians use to research and write histories of the past. Secondary sources, primary sources and material evidence such as that derived from archaeology may all be drawn on, and the historian's skill lies in identifying these sources, evaluating their relative authority, and combining their testimony appropriately in order to construct an accurate and reliable picture of past events and environments.

In the philosophy of history, the question of the nature, and the possibility, of a sound historical method is raised within the sub-field of epistemology. The study of historical method and of different ways of writing history is known as historiography.

Though historians agree in very general and basic principles, in practice "specific canons of historical proof are neither widely observed nor generally agreed upon" among professional historians.[1] Some scholars of history have observed that there are no particular standards for historical fields such as religion, art, science, democracy, and social justice as these are by their nature 'essentially contested' fields, such that they require diverse tools particular to each field beforehand in order to interpret topics from those fields.[2]

Source criticism

[edit]Source criticism (or information evaluation) is the process of evaluating the qualities of an information source, such as its validity, reliability, and relevance to the subject under investigation.

Gilbert J. Garraghan and Jean Delanglez (1946) divide source criticism into six inquiries:[3]

- When was the source, written or unwritten, produced (date)?

- Where was it produced (localization)?

- By whom was it produced (authorship)?

- From what pre-existing material was it produced (analysis)?

- In what original form was it produced (integrity)?

- What is the evidential value of its contents (credibility)?

The first four are known as higher criticism; the fifth, lower criticism; and, together, external criticism. The sixth and final inquiry about a source is called internal criticism. Together, this inquiry is known as source criticism.[citation needed]

R. J. Shafer on external criticism: "It sometimes is said that its function is negative, merely saving us from using false evidence; whereas internal criticism has the positive function of telling us how to use authenticated evidence."[4]

Noting that few documents are accepted as completely reliable, Louis Gottschalk sets down the general rule, "for each particular of a document the process of establishing credibility should be separately undertaken regardless of the general credibility of the author". An author's trustworthiness in the main may establish a background probability for the consideration of each statement, but each piece of evidence extracted must be weighed individually.

Procedures for contradictory sources

[edit]Bernheim (1889) and Langlois & Seignobos (1898) proposed a seven-step procedure for source criticism in history:[5]

- If the sources all agree about an event, historians can consider the event proven.

- However, majority does not rule; even if most sources relate events in one way, that version will not prevail unless it passes the test of critical textual analysis.

- The source whose account can be confirmed by reference to outside authorities in some of its parts can be trusted in its entirety if it is impossible similarly to confirm the entire text.

- When two sources disagree on a particular point, the historian will prefer the source with most "authority"—that is the source created by the expert or by the eyewitness.

- Eyewitnesses are, in general, to be preferred especially in circumstances where the ordinary observer could have accurately reported what transpired and, more specifically, when they deal with facts known by most contemporaries.

- If two independently created sources agree on a matter, the reliability of each is measurably enhanced.

- When two sources disagree and there is no other means of evaluation, then historians take the source which seems to accord best with common sense.

Subsequent descriptions of historical method, outlined below, have attempted to overcome the credulity built into the first step formulated by the nineteenth century historiographers by stating principles not merely by which different reports can be harmonized but instead by which a statement found in a source may be considered to be unreliable or reliable as it stands on its own.

Core principles for determining reliability

[edit]The following core principles of source criticism were formulated by two Scandinavian historians, Olden-Jørgensen (1998) and Thurén Torsten (1997):[6]

- Human sources may be relics such as a fingerprint; or narratives such as a statement or a letter. Relics are more credible sources than narratives.

- Any given source may be forged or corrupted. Strong indications of the originality of the source increase its reliability.

- The closer a source is to the event which it purports to describe, the more one can trust it to give an accurate historical description of what actually happened.

- An eyewitness is more reliable than testimony at second hand, which is more reliable than hearsay at further remove, and so on.

- If a number of independent sources contain the same message, the credibility of the message is strongly increased.

- The tendency of a source is its motivation for providing some kind of bias. Tendencies should be minimized or supplemented with opposite motivations.

- If it can be demonstrated that the witness or source has no direct interest in creating bias then the credibility of the message is increased.

Criteria of authenticity

[edit]Historians sometimes have to deal with deciding what is genuine and what is not in a source. For such circumstances, there are external and internal "criteria of authenticity" that are applicable.[7][8] These are technical tools for evaluating sources and separating 'genuine' sources or content from forgeries or manipulation.[9]

External criteria involve issues relating to establishing authorship of a source or range of sources. It involves things like if an author wrote something themselves, if other sources attribute authorship to the source, agreement of independent manuscript copies on the content of a source.[10]

Internal criteria involve formalities, style, and language for an author; if a source varies from the environment it was produced, inconsistencies of time or chronology, textual transmission of a source, interpolations in a source, insertions or deletions in a source.[11]

Eyewitness evidence

[edit]R. J. Shafer (1974) offers this checklist for evaluating eyewitness testimony:[12]

- Is the real meaning of the statement different from its literal meaning? Are words used in senses not employed today? Is the statement meant to be ironic (i.e., mean other than it says)?

- How well could the author observe the thing he reports? Were his senses equal to the observation? Was his physical location suitable to sight, hearing, touch? Did he have the proper social ability to observe: did he understand the language, have other expertise required (e.g., law, military); was he not being intimidated by his wife or the secret police?

- How did the author report?, and what was his ability to do so?

- Regarding his ability to report, was he biased? Did he have proper time for reporting? Proper place for reporting? Adequate recording instruments?

- When did he report in relation to his observation? Soon? Much later? Fifty years is much later as most eyewitnesses are dead and those who remain may have forgotten relevant material.

- What was the author's intention in reporting? For whom did he report? Would that audience be likely to require or suggest distortion to the author?

- Are there additional clues to intended veracity? Was he indifferent on the subject reported, thus probably not intending distortion? Did he make statements damaging to himself, thus probably not seeking to distort? Did he give incidental or casual information, almost certainly not intended to mislead?

- Do his statements seem inherently improbable: e.g., contrary to human nature, or in conflict with what we know?

- Remember that some types of information are easier to observe and report on than others.

- Are there inner contradictions in the document?

Louis Gottschalk adds an additional consideration: "Even when the fact in question may not be well-known, certain kinds of statements are both incidental and probable to such a degree that error or falsehood seems unlikely. If an ancient inscription on a road tells us that a certain proconsul built that road while Augustus was princeps, it may be doubted without further corroboration that that proconsul really built the road, but would be harder to doubt that the road was built during the principate of Augustus. If an advertisement informs readers that 'A and B Coffee may be bought at any reliable grocer's at the unusual price of fifty cents a pound,' all the inferences of the advertisement may well be doubted without corroboration except that there is a brand of coffee on the market called 'A and B Coffee.'"[13]

Indirect witnesses

[edit]Garraghan (1946) says that most information comes from "indirect witnesses", people who were not present on the scene but heard of the events from someone else.[14] Gottschalk says that a historian may sometimes use hearsay evidence when no primary texts are available. He writes, "In cases where he uses secondary witnesses...he asks: (1) On whose primary testimony does the secondary witness base his statements? (2) Did the secondary witness accurately report the primary testimony as a whole? (3) If not, in what details did he accurately report the primary testimony? Satisfactory answers to the second and third questions may provide the historian with the whole or the gist of the primary testimony upon which the secondary witness may be his only means of knowledge. In such cases the secondary source is the historian's 'original' source, in the sense of being the 'origin' of his knowledge. Insofar as this 'original' source is an accurate report of primary testimony, he tests its credibility as he would that of the primary testimony itself." Gottschalk adds, "Thus hearsay evidence would not be discarded by the historian, as it would be by a law court merely because it is hearsay."[15]

Oral tradition

[edit]Gilbert Garraghan (1946) maintains that oral tradition may be accepted if it satisfies either two "broad conditions" or six "particular conditions", as follows:[16]

- Broad conditions stated.

- The tradition should be supported by an unbroken series of witnesses, reaching from the immediate and first reporter of the fact to the living mediate witness from whom we take it up, or to the one who was the first to commit it to writing.

- There should be several parallel and independent series of witnesses testifying to the fact in question.

- Particular conditions formulated.

- The tradition must report a public event of importance, such as would necessarily be known directly to a great number of persons.

- The tradition must have been generally believed, at least for a definite period of time.

- During that definite period it must have gone without protest, even from persons interested in denying it.

- The tradition must be one of relatively limited duration. [Elsewhere, Garraghan suggests a maximum limit of 150 years, at least in cultures that excel in oral remembrance.]

- The critical spirit must have been sufficiently developed while the tradition lasted, and the necessary means of critical investigation must have been at hand.

- Critical-minded persons who would surely have challenged the tradition – had they considered it false – must have made no such challenge.

Other methods of verifying oral tradition may exist, such as comparison with the evidence of archaeological remains.

More recent evidence concerning the potential reliability or unreliability of oral tradition has come out of fieldwork in West Africa and Eastern Europe.[17]

Anonymous sources

[edit]Historians do allow for the use of anonymous texts to establish historical facts.[18]

Synthesis: historical reasoning

[edit]Once individual pieces of information have been assessed in context, hypotheses can be formed and established by historical reasoning.

Argument to the best explanation

[edit]C. Behan McCullagh (1984) lays down seven conditions for a successful argument to the best explanation:[19]

- The statement, together with other statements already held to be true, must imply yet other statements describing present, observable data. (We will henceforth call the first statement 'the hypothesis', and the statements describing observable data, 'observation statements'.)

- The hypothesis must be of greater explanatory scope than any other incompatible hypothesis about the same subject; that is, it must imply a greater variety of observation statements.

- The hypothesis must be of greater explanatory power than any other incompatible hypothesis about the same subject; that is, it must make the observation statements it implies more probable than any other.

- The hypothesis must be more plausible than any other incompatible hypothesis about the same subject; that is, it must be implied to some degree by a greater variety of accepted truths than any other, and be implied more strongly than any other; and its probable negation must be implied by fewer beliefs, and implied less strongly than any other.

- The hypothesis must be less ad hoc than any other incompatible hypothesis about the same subject; that is, it must include fewer new suppositions about the past which are not already implied to some extent by existing beliefs.

- It must be disconfirmed by fewer accepted beliefs than any other incompatible hypothesis about the same subject; that is, when conjoined with accepted truths it must imply fewer observation statements and other statements which are believed to be false.

- It must exceed other incompatible hypotheses about the same subject by so much, in characteristics 2 to 6, that there is little chance of an incompatible hypothesis, after further investigation, soon exceeding it in these respects.

McCullagh sums up, "if the scope and strength of an explanation are very great, so that it explains a large number and variety of facts, many more than any competing explanation, then it is likely to be true".[20]

Statistical inference

[edit]McCullagh (1984) states this form of argument as follows:[21]

- There is probability (of the degree p1) that whatever is an A is a B.

- It is probable (to the degree p2) that this is an A.

- Therefore, (relative to these premises) it is probable (to the degree p1 × p2) that this is a B.

McCullagh gives this example:[22]

- In thousands of cases, the letters V.S.L.M. appearing at the end of a Latin inscription on a tombstone stand for Votum Solvit Libens Merito.

- From all appearances the letters V.S.L.M. are on this tombstone at the end of a Latin inscription.

- Therefore, these letters on this tombstone stand for Votum Solvit Libens Merito.

This is a syllogism in probabilistic form, making use of a generalization formed by induction from numerous examples (as the first premise).

Argument from analogy

[edit]The structure of the argument is as follows:[23]

- One thing (object, event, or state of affairs) has properties p1 . . . pn and pn + 1.

- Another thing has properties p1 . . . pn.

- So the latter has property pn + 1.

McCullagh says that an argument from analogy, if sound, is either a "covert statistical syllogism" or better expressed as an argument to the best explanation. It is a statistical syllogism when it is "established by a sufficient number and variety of instances of the generalization"; otherwise, the argument may be invalid because properties 1 through n are unrelated to property n + 1, unless property n + 1 is the best explanation of properties 1 through n. Analogy, therefore, is uncontroversial only when used to suggest hypotheses, not as a conclusive argument.

Development

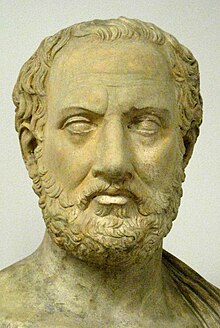

[edit]The development of historical methodology started in the ancient period. Herodotus, from the 5th century BC,[24] has been acclaimed as the "father of history". However, his contemporary Thucydides is credited with having first approached history with a well-developed historical method in the History of the Peloponnesian War. Thucydides, unlike Herodotus, regarded history as the product of the choices and actions of humans, and looked at cause and effect, rather than the result of divine intervention (though Herodotus was not wholly committed to this idea himself).[24] In his historical method, Thucydides emphasized chronology, a nominally neutral point of view, and that the human world was the result of human actions. Greek historians viewed history as cyclical, with events regularly recurring.[25]

There was sophisticated use of historical method in ancient and medieval China. The groundwork for professional historiography in East Asia was established by court historian Sima Qian (145–90 BC), author of the Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji) and posthumously known as the Father of Chinese historiography. Saint Augustine was influential in Christian and Western thought at the beginning of the medieval period. Through the Medieval and Renaissance periods, history was often studied through a sacred or religious perspective. Around 1800, German philosopher and historian Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel brought philosophy and a more secular approach in historical study.[26]

In the preface to his book, the Muqaddimah (1377), the Arab historian and early sociologist, Ibn Khaldun, warned of 7 mistakes he thought historians committed. In this criticism, he approached the past as strange and in need of interpretation. The originality of Ibn Khaldun was to claim that the cultural difference of another age must govern the evaluation of relevant historical material, to distinguish the principles according to which it might be possible to attempt the evaluation, and to feel the need for experience, in addition to rational principles, in order to assess a culture of the past. Ibn Khaldun criticized "idle superstition and uncritical acceptance of historical data". He introduced a scientific method to the study of history, and referred to it as his "new science".[27] His method laid the groundwork for the observation of the role of state, communication, propaganda and systematic bias in history,[28] and so is sometimes considered to be the "father of historiography"[29] [30] or the "father of the philosophy of history".[31]

In the West, historians developed modern methods of historiography in the 17th and 18th centuries, especially in France and Germany. In 1851, Herbert Spencer summarized these methods:"From the successive strata of our historical deposits, they [historians] diligently gather all the highly colored fragments, pounce upon everything that is curious and sparkling and chuckle like children over their glittering acquisitions; meanwhile the rich veins of wisdom that ramify amidst this worthless debris, lie utterly neglected. Cumbrous volumes of rubbish are greedily accumulated, while those masses of rich ore, that should have been dug out, and from which golden truths might have been smelted, are left untaught and unsought."[32]

By the "rich ore" Spencer meant scientific theory of history. Meanwhile, Henry Thomas Buckle expressed a dream of history becoming one day a science: "In regard to nature, events apparently the most irregular and capricious have been explained and have been shown to be in accordance with certain fixed and universal laws. This has been done because men of ability and, above all, men of patient, untiring thought have studied events with the view of discovering their regularity, and if human events were subject to a similar treatment, we have every right to expect similar results.[33] Contrary to Buckle's dream, the 19th-century historian with greatest influence on methods became Leopold von Ranke in Germany. He limited history to "what really happened" and by this directed the field further away from science. For Ranke, historical data should be collected carefully, examined objectively and put together with critical rigor. But these procedures "are merely the prerequisites and preliminaries of science. The heart of science is searching out order and regularity in the data being examined and in formulating generalizations or laws about them."[34]

As Historians like Ranke and many who followed him have pursued it, no, history is not a science. Thus if Historians tell us that, given the manner in which he practices his craft, it cannot be considered a science, we must take him at his word. If he is not doing science, then, whatever else he is doing, he is not doing science. The traditional Historian is thus no scientist and history, as conventionally practiced, is not a science.[35]

In the 20th century, academic historians focused less on epic nationalistic narratives, which often tended to glorify the nation or great men, to more objective and complex analyses of social and intellectual forces. A major trend of historical methodology in the 20th century was to treat history more as a social science rather than art, which traditionally had been the case. Leading advocates of history as a social science were a diverse collection of scholars which included Fernand Braudel and E. H. Carr. Many are noted for their multidisciplinary approach e.g. Braudel combined history with geography. Nevertheless, these multidisciplinary approaches failed to produce a theory of history. So far only one theory of history came from a professional historian.[36] Whatever other theories of history exist, they were written by experts from other fields (for example, Marxian theory of history). The field of digital history has begun to address ways of using computer technology, to pose new questions to historical data and generate digital scholarship.

In opposition to the claims of history as a social science, historians such as Hugh Trevor-Roper argued the key to historians' work was the power of the imagination, and hence contended that history should be understood as art. French historians associated with the Annales school introduced quantitative history, using raw data to track the lives of typical individuals, and were prominent in the establishment of cultural history (cf. histoire des mentalités). Intellectual historians such as Herbert Butterfield have argued for the significance of ideas in history. American historians, motivated by the civil rights era, focused on formerly overlooked ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic groups. A genre of social history to emerge post-WWII was Alltagsgeschichte (History of Everyday Life). Scholars such as Ian Kershaw examined what everyday life was like for ordinary people in 20th-century Germany, especially in Nazi Germany.

The Marxist theory of historical materialism theorises that society is fundamentally determined by the material conditions at any given time – in other words, the relationships which people have with each other in order to fulfill basic needs such as feeding, clothing and housing themselves and their families.[37] Overall, Marx and Engels claimed to have identified five successive stages of the development of these material conditions in Western Europe.[38] Marxist historiography was once orthodoxy in the Soviet Union, but since the communism's collapse there, its influence has significantly reduced.[39]

Marxist historians sought to validate Karl Marx's theories by analyzing history from a Marxist perspective. In response to the Marxist interpretation of history, historians such as François Furet have offered anti-Marxist interpretations of history. Feminist historians argued for the importance of studying the experience of women. Postmodernists have challenged the validity and need for the study of history on the basis all history is based on the personal interpretation of sources. Keith Windschuttle's 1994 book, The Killing of History defended the worth of history.

Today, most historians begin their research in archives, on either a physical or digital platform. They often propose an argument and use research to support it. John H. Arnold proposed that history is an argument, which creates the possibility of creating change.[40] Digital information companies, such as Google, have sparked controversy over the role of internet censorship in information access.[41]

See also

[edit]- Antiquarian

- Archaeology

- Archival research

- Auxiliary sciences of history

- Chinese whispers

- Historical criticism

- Historical significance

- Historiography

- List of history journals

- Philosophy of history

- Recorded history

- Scholarly method

- Scientific method

- Source criticism

- Unwitting testimony

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Fischer, David Hackett (1970). Historians' Fallacies: Toward a Logic of Historical Thought. New York: Harper Perennial. p. 62. ISBN 9780061315459.

Historians are likely to agree in principle, but not in practice. Specific canons of historical proof are neither widely observed nor generally agreed upon.

- ^ McCullagh, C. Behan (2000). "Bias in Historical Description, Interpretation, and Explanation". History and Theory. 39 (1): 47. doi:10.1111/0018-2656.00112. ISSN 0018-2656. JSTOR 2677997.

W. B. Gallie argued that some concepts in history are "essentially contested," namely "religion," "art," "science," "democracy," and "social justice." These are concepts for which "there is no one use of any of them which can be set up as its generally accepted and therefore correct or standard use. When historians write the history of these subjects, they must choose an interpretation of the subject to guide them. For instance, in deciding what Art is, historians can choose between "configurationist theories, theories of aesthetic contemplation and response .. ., theories of art as expression, theories emphasizing traditional artistic aims and standards, and communication theories.

- ^ Gilbert J. Garraghan and Jean Delanglez A Guide to Historical Method p. 168, 1946

- ^ A Guide to Historical Method, p. 118, 1974

- ^ Howell, Martha & Prevenier, Walter(2001). From Reliable Sources: An Introduction to Historical Methods. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8560-6.

- ^ Thurén, Torsten. (1997). Källkritik. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- ^ Gilbert J. Garraghan and Jean Delanglez A Guide to Historical Method p. 174, "Criteria of Authenticity" 1946

- ^ A Guide to Historical Method, p. 25-26, 1974

- ^ Howell, Martha & Prevenier, Walter(2001). From Reliable Sources: An Introduction to Historical Methods. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8560-6. p. 56-59

- ^ Gilbert J. Garraghan and Jean Delanglez A Guide to Historical Method p. 174-177, 1946

- ^ Gilbert J. Garraghan and Jean Delanglez A Guide to Historical Method p. 177-184, 1946

- ^ A Guide to Historical Method, pp. 157–158, 1974

- ^ Understanding History, p. 163

- ^ A Guide to Historical Method, p. 292, 1946

- ^ Understanding History, 165-66

- ^ A Guide to Historical Method, 261–262, 1946)

- ^ See J. Vansina, De la tradition orale. Essai de méthode historique, in translation as Oral Tradition as History, as well as A. B. Lord's study of Slavic bards in The Singer of Tales. Note also the Icelandic sagas, such as that by Snorri Sturlason in the 13th century, and K. E. Bailey, "Informed Controlled Oral Tradition and the Synoptic Gospels", Asia Journal of Theology [1991], 34–54. Compare Walter J. Ong, Orality and Literacy.

- ^ Gottschalk,A Guide to Historical Method, 169, 1950)

- ^ Justifying Historical Descriptions, p. 19, 1984

- ^ Justifying Historical Descriptions, p. 26, 1984

- ^ Justifying Historical Descriptions, 48, 1984

- ^ Justifying Historical Descriptions, p. 47, 1984

- ^ Justifying Historical Descriptions, p. v85, 1984

- ^ a b Lamberg-Karlovsky, C.C.; Jeremy A. Sabloff (1979). Ancient Civilizations: The Near East and Mesoamerica. Benjamin-Cummings Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 9780881338348.

- ^ Lamberg-Karlovsky, C.C.; Jeremy A. Sabloff (1979). Ancient Civilizations: The Near East and Mesoamerica. Benjamin-Cummings Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 9780881338348.

- ^ Graham, Gordon (1997). "Chapter 1". The Shape of the Past. University of Oxford.

- ^ Ibn Khaldun; Rosenthal, Franz; Dawood, N.J. (1967). The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History. Princeton University Press. p. x. ISBN 0691017549.

- ^ H. Mowlana (2001). "Information in the Arab World", Cooperation South Journal, vol1

- ^ Ahmed, Salahuddin (1999). A Dictionary of Muslim Names. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 1850653569.

- ^ Enan, Muhammed Abdullah (2007). Ibn Khaldun: His Life and Works. The Other Press. p. v. ISBN 9789839541533.

- ^ S.W. Akhtar (1997). "The Islamic Concept of Knowledge", Al-Tawhid: A Quarterly Journal of Islamic Thought & Culture 12 (3).

- ^ Cited in Robert Carneiro, The Muse of History and the Science of Culture, New York: Kluwer Publishers, 2000, p 160.

- ^ Cited in Muse of History, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Muse of History, p 147.

- ^ Muse of History, p 150.

- ^ Max Ostrovski, The Hyperbole of the World Order, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006.

- ^ See, in particular, Marx and Engels, The German Ideology Archived 22 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Marx makes no claim to have produced a master key to history. Historical materialism is not "an historico-philosophic theory of the marche generale imposed by fate upon every people, whatever the historic circumstances in which it finds itself" (Marx, Karl: Letter to editor of the Russian paper Otetchestvennye Zapiskym, 1877). His ideas, he explains, are based on a concrete study of the actual conditions that pertained in Europe.

- ^ Mikhail M. Krom, "From the Center to the Margin: the Fate of Marxism in Contemporary Russian Historiography", Storia della Storiografia (2012) Issue 62, pp. 121–130

- ^ Arnold, John H. (2000). History: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 019285352X.

- ^ King, Michelle T. (2016). "Working With/In the Archives". Research Methods for History (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

References

[edit]- Gilbert J. Garraghan, A Guide to Historical Method, Fordham University Press: New York (1946). ISBN 0-8371-7132-6

- Louis Gottschalk, Understanding History: A Primer of Historical Method, Alfred A. Knopf: New York (1950). ISBN 0-394-30215-X.

- Martha Howell and Walter Prevenier, From Reliable Sources: An Introduction to Historical Methods, Cornell University Press: Ithaca (2001). ISBN 0-8014-8560-6.

- C. Behan McCullagh, Justifying Historical Descriptions, Cambridge University Press: New York (1984). ISBN 0-521-31830-0.

- Presnell, J. L. (2019). The information-literate historian: a guide to research for history students (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- R. J. Shafer, A Guide to Historical Method, The Dorsey Press: Illinois (1974). ISBN 0-534-10825-3.

External links

[edit]- Introduction to Historical Method by Marc Comtois

- Philosophy of History Archived 2005-09-05 at the Wayback Machine by Paul Newall

- Federal Rules of Evidence in United States law