History of the Royal Marines

The history of the Royal Marines began on 28 October 1664 with the formation of the Duke of York and Albany's Maritime Regiment of Foot soon becoming known as the Admiral's Regiment. During the War of the Spanish Succession the most historic achievement of the Marines was the capture of the mole during the assault on Gibraltar (sailors of the Royal Navy captured the Rock itself) in 1704. On 5 April 1755, His Majesty's Marine Forces, fifty Companies in three Divisions, headquartered at Portsmouth, Chatham and Plymouth, were formed by Order of Council under Admiralty control.

The Royal Marine Artillery was formed as an establishment within the British Royal Marines in 1804 to man the artillery in bomb vessels. As their coats were the blue of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, this group was nicknamed the "Blue Marines" and the Infantry element, who wore the scarlet coats of the British infantry, became known as the "Red Marines". During the Napoleonic Wars the Royal Marines participated in every notable naval battle on board the Royal Navy's ships and also took part in multiple amphibious actions. Marines had a dual function aboard ships of the Royal Navy; routinely, they ensured the security of the ship's officers and supported their maintenance of discipline in the ship's crew, and in battle, they engaged the enemy's crews, whether firing from positions on their own ship, or fighting in boarding actions.

During the First World War, in addition to their usual stations aboard ship, Royal Marines were part of the Royal Naval Division which landed in Belgium in 1914 to help defend Antwerp and later took part in the amphibious landing at Gallipoli in 1915. The Royal Marines also took part in the Zeebrugge Raid in 1918. During the Second World War the Infantry Battalions of the Royal Marine Division were re-organised as Commandos, joining the British Army Commandos. The Division command structure became a Special Service Brigade command. The support troops became landing craft crew and saw extensive action on D-Day in June 1944.

The Falklands War provided the backdrop to the next action of the Royal Marines. Argentina invaded the islands in April 1982. A British task force was immediately dispatched to recapture them, and given that an amphibious assault would be necessary, the Royal Marines were heavily involved. The troops were landed at San Carlos Water at the western end of East Falkland, and proceeded to "yomp" across the entire island to the capital, Stanley, which fell on 14 June 1982.

Origin

[edit]The 'first official' unit of English naval infantry, originally called the Duke of York and Albany's Maritime Regiment of Foot and soon becoming known as the Admiral's Regiment, was formed on 28 October 1664, with an initial strength of 1,200 infantrymen recruited from the Trained Bands of London as part of the mobilisation for the Second Anglo-Dutch War. James (later King James VII & II), the Duke of York and Albany, Lord High Admiral and brother of King Charles II, was Captain-General of the Artillery Company, now the Honourable Artillery Company, the unit that trained the Trained Bands.[1]

It was the fifth European Marine unit formed, being preceded by the Spain's Infantería de Marina (1537), the Fanti da Mar of the Republic of Venice (1550), the Portuguese Marine Corps (1610) and France's Troupes de marine (1622). It consisted of six 200-man companies and was initially commanded by Colonel Sir William Killigrew with Sir Charles Lyttleton as lieutenant-colonel. Killigrew had commanded an English regiment in Dutch service, and many of the regiment's initial complement of officers had served there as well.[2]

The Holland Regiment (later The Buffs) was also raised to serve at sea and both of these "Naval" regiments were paid for by the Treasurer of the Navy by Order of Council of 11 July 1665.[3] John Churchill, later the 1st Duke of Marlborough, was a famous member of this regiment. A Company of Foot Guards served as Marines to augment the Marines of the Admiral's Regiment during the key sea battle the Battle of Solebay in 1672. The regiment was disbanded in 1689 shortly after James II was deposed in the Glorious Revolution.[3]

Two marine regiments of the army were raised in 1690. They were the Earl of Pembroke's and Torrington's, later Lord Berkeley's.[1] These two regiments participated in an opposed landing during the Williamite War in Ireland at Cork, Ireland on 21 September 1690 under the command of John Churchill, later Duke of Marlborough.[4]

In 1698, the Marine establishment was reformed: the two existing regiments were reformed into a single one under the command of Thomas Brudenell, while the foot regiments of William Seymour, Edward Dutton Colt, and Harry Mordaunt were converted into Marine regiments.[5] These regiments were disbanded in 1699.[6]

In 1702, six Regiments of Marines and six Sea Service Regiments of Foot were formed for the War of the Spanish Succession. When on land, the Marines were commanded by Brigadier-General Seymour, also Colonel of the 4th Foot. Their most significant achievement was the capture of the mole during the assault on Gibraltar (sailors of the Royal Navy captured the Rock itself) and the subsequent defence of the fortress alongside the Dutch Marines in 1704.[7] After the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, three of these were redesignated as line infantry, becoming the 30th, 31st and 32nd Foot.[8]

Eighteenth century

[edit]Six Marine Regiments (1st to 6th Marines, 44th to 49th Foot) were raised on 17–22 November 1739 for the War of Jenkins' Ear, with four more being raised later. One large Marine Regiment (Spotswood's Regiment, later Gooch's American Regiment) was formed of American colonists and served alongside British Marines at the Battle of Cartagena de Indias, Colombia and Guantánamo Bay, Cuba in the War of Jenkins' Ear (1741). Among its officers was Lawrence Washington, the half-brother of George Washington.[9] In 1747, the remaining regiments were transferred to the Admiralty and then disbanded in 1748. Many of the disbanded men were offered transportation to Nova Scotia and helped form the city of Halifax, Nova Scotia.[10]

On 5 April 1755, His Majesty's Marine Forces, fifty Companies in three Divisions, headquartered at Portsmouth, Chatham and Plymouth, were formed by Order of Council under Admiralty control.[1] Initially, all field officers were Royal Navy officers as the Royal Navy felt that the ranks of Marine field officers were largely honorary. This meant that the farthest a Marine officer could advance was to lieutenant colonel. It was not until 1771 that the first Marine was promoted to colonel. This situation persisted well into the 1800s. During the rest of the 18th century, they served in numerous landings all over the world, the most famous being the landing at Bellisle on the Brittany coast in 1761.[1] They also served in the American War of Independence. A company of Marines under the command of Major John Pitcairn broke the rebel resistance in the Battle of Bunker Hill and took possession of the enemy redoubt.[11] These Marines also often took to the ship's boats to repel attackers in small boats when RN ships were becalmed on close blockade. Captain James Cook took with him four marines on the day he was killed in Hawaii, 14 February 1779, Corporal James Thomas, Private Theophilus Hinks, Private Thomas Fatchett and Private John Allen.[12]

New South Wales

[edit]From May 1787, a detachment of four companies of marines, under Major Robert Ross, accompanied the First Fleet to protect a new colony at Botany Bay (New South Wales). Due to an administrative error the Fleet left Portsmouth without its main supply of ammunition, cartridge paper and tools to repair their flintlocks. The omission was noted early during the voyage and, in July 1787, a request was sent back to the British Home Office from Santa Cruz that the missing supplies be sent out in William Bligh's ship HMS Bounty. Ten thousand rounds of ammunition were also obtained when the Fleet called into Rio de Janeiro en route to Botany Bay.[13] However, despite the Home Office receiving the request, the full resupply was never sent and consequently, after 12 months, the marines ended up in difficult circumstances.[14]

The First Fleet detachment had a strength of 212 including 160 privates. This relatively small force was arranged on the advice of Joseph Banks who advised the British government that local Aborigines were few and retiring. On arrival in New South Wales in January 1788 the Governor of the new colony, naval Captain Arthur Phillip, found that the natives were vastly more numerous than expected and also that they soon started resisting the settlers. Within 12 months, natives killed 5 or 6 First Fleeters and wounded others. Finally, in October 1788, the marines were tasked to expand the initial settlement at Sydney Cove to commence farming more fertile land at Parramatta.[15]

One author has claimed that the Marines deliberately spread smallpox among Australia's indigenous population in order to reduce its military effectiveness,[14] but this is not corroborated by contemporaneous records of the settlement and most researchers attribute the indigenous smallpox outbreak to other causes.[14][16]

Nineteenth century

[edit]In 1802, largely at the instigation of Admiral John Jervis, 1st Earl of St Vincent, they were titled the Royal Marines by King George III.[17]

The Royal Marine Artillery (RMA) was formed as an establishment within the British Royal Marines in 1804 to man the artillery in bomb vessels. This had been done by the Royal Regiment of Artillery, but a lawsuit by a Royal Artillery officer resulted in a court decision that army officers were not subject to naval orders. As their coats were the blue of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, this group was nicknamed the "Blue Marines" and the infantry element, who wore the scarlet coats of the British infantry, became known as the "Red Marines", often given the derogatory nickname "Lobsters" by sailors.[18]

French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

[edit]At the start of the conflict, there were insufficient numbers of marines, so army personnel were used for 4 years to address this shortfall.[19] During the Napoleonic Wars the Royal Marines participated in every notable naval battle on board the Royal Navy's ships and also took part in multiple amphibious actions. Marines had a dual function aboard ships of the Royal Navy in this period; routinely, they ensured the security of the ship's officers and supported their maintenance of discipline in the ship's crew, and in battle, they engaged the enemy's crews, whether firing from positions on their own ship, or fighting in boarding actions.[20]

The number of marines on board Royal Naval ships depended on the size of the ship and was generally kept at a ratio of one marine per ship gun, plus officers. For example: a First Rate Ship of the Line contained 104 marines while a 28 gun Frigate had 29. Between 1807 and 1814, the total marine establishment number was 31,400 men. Manpower (recruitment and retention) problems saw regular infantry units from the British Army being used as shipboard replacements on numerous occasions. One result of the Royal Navy's dominance of the seas in Europe, and the blockading of the French Navy's ports, was that manpower constraints became less of an issue at the end of the Napoleonic Wars. From 1812, such maritime supremacy meant the Mediterranean and Channel Fleets were assigned additional marines for use 'in destroying signal communications and other petty harassing modes of warfare'.[21]

In the Caribbean theatre volunteers from freed French slaves on Marie-Galante were used to form the 1st Corps of Colonial Marines. These men bolstered the ranks, helping the British to hold the island until reinforcements arrived. This practice was repeated during the War of 1812, where escaped American slaves were formed into the 2nd Corps of Colonial Marines. These men were commanded by Royal Marines officers and fought alongside their regular Royal Marines counterparts at the Battle of Bladensburg in August 1814.[22] During the battle a detachment of Royal Marine Artillery commanded by Lieutenant John Lawrence deployed Congreve rockets resulting in the rout of the US militiamen.[23] The Royal Marines battalion and the 21st Regiment of Foot also took part in the Burning of Washington later that day.[24]

Also present on shore during the Chesapeake campaign was a composite battalion of Marines, formed from ships' Marine detachments, frequently led by Captain John Robyns. A smaller composite battalion of about 100 men (23 officers,[25] two of whom (John Wilson 1787–1850 and John Alexander Phillips 1790–1865) were Trafalgar veterans, and 80 other ranks) also took part in the Battle of New Orleans, under the command of Brevet Major Thomas Adair, in January 1815. The only British success at New Orleans was an attack on the west bank of the Mississippi River by a 700-man force, consisting of the 100 Royal Marines, 100 sailors under Captain Rowland Money, and 3 companies of the 85th Foot.[26]

Throughout the war Royal Marines units raided up and down the east coast of America including up the Penobscot River and in the Chesapeake Bay. They later helped capture Fort Bowyer in Mobile Bay in what was the last action of the war.[27]

Crimean War and beyond

[edit]

In 1855, the marine Infantry forces were renamed the Royal Marines Light Infantry (RMLI) and in 1862 the name was slightly altered to Royal Marine Light Infantry.[1] The Royal Navy only saw limited active service at sea after 1850 (until 1914) and became interested in developing the concept of landings by Naval Brigades. In these Naval Brigades, the function of the Royal Marines was to land first and act as skirmishers ahead of sailors trained as conventional infantry and artillery. This skirmishing was the traditional function of light infantry.[28]

During the Crimean War in 1854 and 1855, three Royal Marines earned the Victoria Cross, two in the Crimea and one in the Baltic.[29]

For most of their history, British Marines had been organised as fusiliers. In the rest of the 19th Century the Royal Marines served in many landings especially in the First and Second Opium Wars (1839–1842 and 1856–1860) against the Chinese. These were all successful except for the landing at the Mouth of the Peiho in 1859, where Admiral Sir James Hope ordered a landing across extensive mud flats.[30]

Early 20th century

[edit]The Royal Marines also played a prominent role in the Boxer Rebellion in China (1900), where a Royal Marine earned a further Corps Victoria Cross.[29]

Pursuing a career in the Marines had been considered social suicide through much of the 18th and 19th centuries since Marine officers had a lower standing than their counterparts in the Royal Navy. An effort was made in 1907 through the common entry or "Selborne scheme" to reduce the professional differences between RN and RM officers through a system of common entry that provided for an initial period of service where both groups performed the same roles and underwent the same training.[31]

For the first part of the 20th century, the Royal Marines' role was the traditional one of providing shipboard infantry for security, boarding parties and small-scale landings. The Marines' other traditional position on a Royal Navy ship was manning 'X' and 'Y' (the aftermost) gun turrets on a battleship or cruiser.[32]

First World War

[edit]During the First World War, in addition to their usual stations aboard ship, Royal Marines were part of the Royal Naval Division which landed in Belgium in 1914 to help defend Antwerp and later took part in the amphibious landing at Gallipoli in 1915. It also served on the Western Front. The division's first two commanders were Royal Marine Artillery Generals. Other Royal Marines acted as landing parties in the naval campaign against the Turkish fortifications in the Dardanelles before the Gallipoli landing. They were sent ashore to assess damage to Turkish fortifications after bombardment by British and French ships and, if necessary, to complete their destruction. The Royal Marines were the last to leave Gallipoli, replacing both British and French troops in a neatly planned and executed withdrawal from the beaches.[33]

The Royal Marines also took part in the Zeebrugge Raid in 1918. Five Royal Marines earned the Victoria Cross in the First World War, two at Zeebrugge, one at Gallipoli, one at Jutland and one on the Western Front.[29]

Between the World Wars

[edit]After the war Royal Marines took part in the allied intervention in Russia. In 1919, the 6th Battalion RMLI mutinied and was disbanded at Murmansk. The Royal Marine Artillery (RMA) and Royal Marine Light Infantry (RMLI) were amalgamated on 22 June 1923.[34] Post-war demobilisation had seen the Royal Marines reduced from 55,000 (1918) to 15,000 in 1922 and there was Treasury pressure for a further reduction to 6,000 or even the entire disbandment of the Corps. As a compromise an establishment of 9,500 was settled upon but this meant that two separate branches could no longer be maintained. The abandonment of the Marines' artillery role meant that the Corps would subsequently have to rely on Royal Artillery support when ashore, that the title of Royal Marines would apply to the entire Corps and that only a few specialists would now receive gunnery training. As a form of consolation the dark blue and red uniform of the Royal Marine Artillery now became the full dress of the entire Corps. Royal Marine officers and SNCOs however continue to wear the historic scarlet in mess dress to the present day. The ranks of Private, used by the RMLI, and Gunner, used by the RMA, were abolished and replaced by the rank of Marine.[35]

Second World War

[edit]During the Second World War, a small party of Royal Marines were first ashore at Namsos in April 1940, seizing the approaches to the Norwegian town preparatory to a landing by the British Army two days later. The Royal Marines formed the Royal Marines Division as an amphibiously trained division, parts of which served at Dakar and in the capture of Madagascar. After the assault on the French naval base at Antsirane in Madagascar was held up, fifty Sea Service Royal Marines from HMS Ramilles commanded by Captain Martin Price were landed on the quay of the base by the British destroyer HMS Anthony after it ran the gauntlet of French shore batteries defending Diego Suarez Bay. They then captured two of the batteries, which led to a quick surrender by the French.[36]

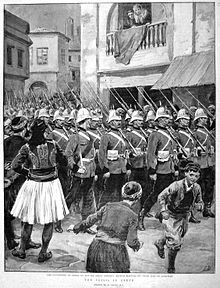

In addition the Royal Marines formed Mobile Naval Base Defence Organisations (MNBDOs) similar to the United States Marine Corps Defense Battalions. One of these took part in the defence of Crete. Royal Marines also served in Malaya and in Singapore, where due to losses they were joined with remnants of the 2nd Battalion, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders to form the "Plymouth Argylls".

The first Royal Marines commando unit was formed at Deal in Kent on 14 February 1942 and designated 'The Royal Marine Commando',[37] shortly afterwards it was renamed A Commando and took part in the Dieppe Raid. One month after Dieppe, most of the 11th Royal Marine Battalion was killed or captured in an ill staged amphibious landing at Tobruk in Operation Agreement, again the Marines were involved with the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, this time the 1st Battalion. In 1942 the Infantry Battalions of the Royal Marine Division were re-organised as Commandos, joining the British Army Commandos. The Division command structure became a Special Service Brigade command. The support troops became landing craft crew and saw extensive action on D-Day in June 1944.[38]

A total of four Special Service Brigades (later Commando brigade) were raised during the war, and Royal Marines were represented in all of them. A total of nine RM Commandos were raised during the war, numbered from 40 to 48. These were distributed as follows:[39]

- 1 Commando Brigade

- 2 Commando Brigade

- 3 Commando Brigade

- 4 Commando Brigade (entirely Royal Marine after March 1944)

1 Commando Brigade took part in first in the Tunisia Campaign and then assaults on Sicily and Normandy, campaigns in the Rhineland and crossing the Rhine. 2 Commando Brigade was involved in the Salerno landings, Anzio, Comacchio, and operations in the Argenta Gap. 3 Commando Brigade served in Sicily and Burma. 4 Commando Brigade served in the Battle of Normandy and in the Battle of the Scheldt on the island of Walcheren during the clearing of Antwerp.[40]

In January 1945, two further RM brigades were formed, 116th Brigade and 117th Brigade. Both were conventional infantry, rather than in the commando role. 116th Brigade saw some action in the Netherlands, but 117th Brigade was hardly used operationally.[41]

A number of Royal Marines served as pilots during the Second World War. It was a Royal Marines officer who led the attack by a formation of Blackburn Skuas that sank the Königsberg. Eighteen Royal Marines commanded Fleet Air Arm squadrons during the course of the war, and with the formation of the British Pacific Fleet were well-represented in the final drive on Japan. Captains and majors generally commanded squadrons, whilst in one case Lt. Colonel R.C. Hay on HMS Indefatigable was Air Group Co-ordinator from HMS Victorious of the entire British Pacific Fleet.[42]

Crews for the UK's landing craft were initially drawn from the Royal Navy, after 1 April 1943 this responsibility was transferred to the Royal Marines. RM officers did a preliminary 9 week course 6 at HMS Eastney and 3 weeks in craft at HMS Northney (Hayling Island). From there they were appointed to HMS Helder or HMS Effingham for 6 week courses in training with their crews.[43]

They also provided the crews for the UK's minor landing craft, and the Royal Marines Armoured Support Group manned Centaur IV tanks on D Day; one of these is still on display at Pegasus Bridge.[44]

Only one Marine (Corporal Thomas Peck Hunter of 43 Commando) was awarded the Victoria Cross in the Second World War for action at Lake Comacchio in Italy. Hunter was the most recent RM commando to be awarded the medal.[29]

The Royal Marines Boom Patrol Detachment under Blondie Haslar carried out Operation Frankton and provided the basis for the post-war continuation of the SBS.[45]

After 1945

[edit]

In 1946 the Army Commandos were disbanded, leaving the Royal Marines to continue the commando role (with supporting army elements).

Royal Marines were involved in the Korean War. 41 (Independent) Commando was reformed in 1950, and was originally envisaged as a raiding force for use against North Korea. It performed this role in partnership with the United States Navy until after the landing of United States Army X Corps at Wonsan. It then joined the US's 1st Marine Division at Koto-Ri. As Task Force Drysdale with Lt. Col. D.B. Drysdale RM in command, 41 Commando, a USMC company, a US Army company and part of the divisional train fought their way from Koto-Ri to Hagaru after the Chinese had blocked the road to the North. It then took part in the famous withdrawal from Chosin Reservoir. After that, a small amount of raiding followed, before the Marines were withdrawn from the conflict in 1951. It received the Presidential Citation after the USMC got the regulations modified to allow foreign units to receive the award.[46]

After playing a part in the long-running Malayan Emergency, the next action came in 1956, during the Suez Crisis. Headquarters 3 Commando Brigade, and Nos 40, 42 and 45 Commandos took part in the operation. It marked the first time that a helicopter assault was used operationally to land troops in an amphibious attack. British and French forces defeated the Egyptians, but after pressure from the United States, and French domestic pressure, they backed down.[47]

In September 1955 45 Commando was deployed to Cyprus to undertake anti-terrorist operations against the EOKA guerrillas during the independence war against the British. The EOKA were a small, but powerful organisation of Greek Cypriots, who had great local support from the Greek community. The unit, based in Malta at the time travelled to the Kyrenia mountain area of the island and in December 1955 launched Operation Foxhunter, an operation to destroy EOKA's main base.[48]

Further action in the Far East was seen during the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation. Nos 40 and 42 Commando went to Borneo at various times to help keep Indonesian forces from worsening situations in the neighbouring region, in what was an already heated part of the world, with conflicts in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. During the campaign there was a company-strength amphibious assault by Lima Company of 42 Commando at the town of Limbang to rescue hostages. The Limbang raid saw three of the 150 marines involved decorated, L company 42 commando are still referred to today as Limbang Company in memory of this archetypal commando raid.[49]

In January 1964, part of the Tanzanian Army mutinied. Within 24 hours elements of 41 Commando had left Bickleigh Camp, Plymouth, Devon, and were travelling by air to Nairobi, Kenya, continuing by road into Tanzania. At the same time, Commandos aboard HMS Bulwark sailed to East Africa and anchored off-shore from Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. The revolt was put down and the next six months were spent in touring Tanzanian military out-posts disarming military personnel.[50]

From 1969 onwards, Royal Marine units regularly deployed to Northern Ireland during The Troubles, during the course of which 13 were killed in action.[51] A further eleven died in the Deal barracks bombing of the Royal Marines School of Music in 1989.[52]

Between 1974 and 1984, the Royal Marines undertook three United Nations tours of duty in Cyprus. The first was in November 1974, when 41 Commando took over the Limassol District from the 2nd Battalion of the Guards Brigade, following the Turkish invasion, and became the first commando to wear the light blue berets of the UN when they began the Corps' first six-month tour with the UN forces in Cyprus (UNIFCYP).[53]

The Falklands War provided the backdrop to the next action of the Royal Marines. Argentina invaded the islands in April 1982. A British task force was immediately despatched to recapture them, and given that an amphibious assault would be necessary, the Royal Marines were heavily involved. 3 Commando Brigade was brought to full combat strength, with not only 40, 42 and 45 Commandos, but also the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the Parachute Regiment attached. The troops were landed at San Carlos Water at the western end of East Falkland, and proceeded to "yomp" across the entire island to the capital, Stanley, which fell on 14 June 1982 to 2nd Battalion The Parachute Regiment. A Royal Marines divisional headquarters was deployed, under Major-General Jeremy Moore, who was commander of British land forces during the war.[54]

The main element of 3 Commando Brigade was not deployed in the 1991 Gulf War. However, 24 men from K Company, 42 Commando Royal Marines were deployed as six-man teams aboard two Royal Navy destroyers and frigates. They were used as ship boarding parties and took part in numerous boardings of suspect shipping. There were also further elements deployed to provide protection of shipping whilst in ports throughout the Gulf. The main element of 3 Commando Brigade was deployed to northern Iraq in the aftermath to provide aid to the Iraqi Kurds as part of Operation Safe Haven.[55]

In 1992 recruiting into the RM Band Service was opened to females.[56]

From 2000 onwards, the Royal Marines began converting from their traditional light infantry role with the introduction of the Commando 21 concept, an emphasis on force protection leading to the introduction of the Viking, the first armoured vehicle to be operated by the Royal Marines for half a century.[57]

In November 2001, after the seizure of Bagram Air Base by the Special Boat Service, Charlie Company of 40 Commando became the first British regular forces into Afghanistan, using Bagram Air base to support British and US Special Forces Operations.[58]

2002 saw the deployment of 45 Commando Royal Marines to Afghanistan, where contact with enemy forces was expected to be heavy. However little action was seen, with no Al-Qaeda or Taliban forces being found or engaged.[59]

3 Commando Brigade deployed on Operation TELIC, the British involvement in the Iraq war, in early 2003 with the USMC's 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit under its command. The Brigade conducted an amphibious assault on the Al-Faw Peninsula in Iraq in support of US Navy SEALs. The 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit and 42 Commando securing the port of Umm Qasr and 40 Commando conducting a helicopter assault in order to secure the oil installations to assure continued operability of Iraq's export capability. The attack proceeded well, with light casualties. 3 Commando Brigade served as part of the US 1st Marine Division and received the US Presidential Unit Citation, in fact the 2nd time in 50 years the Royal Marines received this.[60]

In 2004, Iranian armed forces took Royal Navy personnel prisoner, including six Royal Marines, on the Shatt al-Arab (Arvand Rud in Persian) river, between Iran and Iraq.[61] They were released three days later following diplomatic discussions between the UK and Iran.

In November 2006, 3 Commando Brigade relieved 16 Air Assault Brigade of the British Army in Helmand Province, Afghanistan, as part of Operation Herrick.[62]

In 2007, Iranian armed forces also took prisoner Royal Navy personnel, including seven Royal Marines, when a boarding party from HMS Cornwall was seized in the waters between Iran and Iraq, in the Persian Gulf.[63]

In 2008, Lance-Corporal Matthew Croucher of 40 Commando was awarded the George Cross (GC) after throwing himself on a grenade to save the lives of the other marines in his patrol, in Afghanistan. Remarkably, he managed to keep his rucksack between himself and the grenade, and that, together with his body armour, meant he suffered only very minor injuries.[64]

In 2018, women became eligible to apply for all roles in the British forces, including the Royal Marines beyond the Band Service where they have served since 1992.[65]

In 2024, 3 Commando Brigade was rebranded as the United Kingdom Commando Force (UKCF).[66]

Shore bases

[edit]When first permanently established (1755), the Marines were formed into three Divisions based in the three principal Royal Navy Dockyards: Portsmouth, Chatham and Plymouth.[1]

18th century

[edit]The Royal Marines was the first complete British corps to be provided with its own barracks – one for each Division:[67]

- The Royal Marine Barracks, Portsmouth were established in 1768[68] but the premises did not prove altogether satisfactory, and in 1848 the Portsmouth Division was relocated to Forton Barracks in nearby Gosport.[69]

- The Royal Marine Barracks, Chatham was opened in 1779 and remained in use until 1950 (when Chatham ceased to operate as a naval base).[70]

- The Royal Marine Barracks, Plymouth were established in 1756 and, as Stonehouse Barracks still form the headquarters of 3 Commando Brigade.[71]

19th and 20th centuries

[edit]In 1805 a fourth division was established, based at Woolwich (site of another Royal Dockyard). The Royal Marine Barracks, Woolwich and Infirmary were built there (in Frances Street) between 1842 and 1848; both were progressive designs for their time. After the closure of the dockyard, the division was disbanded (1869). The buildings were handed over to the army and were renamed Cambridge Barracks: they were largely demolished in 1975 but the gatehouse remains.[72]

In 1861 the Royal Marine Depot, Deal was established alongside the important naval anchorage known as the Downs. It was initially served by Marines from the Chatham, Portsmouth and Woolwich Divisions. The Depot remained in service until 1991 although the Royal Marines School of Music remained on site until 1996.[73]

The Royal Marine Artillery was initially based at Chatham, but in 1824 was moved to its own dedicated barracks, Gunwharf Barracks, in Portsmouth. In 1858 the Royal Marine Artillery moved from there to Fort Cumberland (which continued to be used for gunnery training into the 20th century). The establishment of the Royal Marine Artillery as a separate unit in 1859 led to Eastney Barracks being built to accommodate them; the barracks were opened at Eastney in 1867.[74]

Following the amalgamation of the RM Artillery and Light Infantry in 1923, Forton Barracks was closed and Eastney became the Corps' main base in Portsmouth.[75] Eastney Barracks remained the Corps Headquarters until 1995, when it was sold and converted to private housing.[76]

See also

[edit]- 4th Special Service Brigade

- Corps of Colonial Marines

- History of the Royal Navy

- Royal Marines Band Service

- Royal Marines Museum

- Uniforms of the Royal Marines

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Royal Marines History and Traditional Facts" (PDF). Marine Society & Sea Cadet. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "Killigrew, Sir William II (1606–1695), of Pendennis Castle, Cornwall; later of Lincoln's Inn Fields, London and Kempton Park, Middlesex". History of Parliament. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ a b "The Buffs (East Kent Regiment)" (PDF). Kent Fallen. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ^ Lenihan, p. 184

- ^ Edye, p. 521–522

- ^ Edye, p. 577-578

- ^ Francis, p. 110

- ^ "32nd (Cornwall Light Infantry) Regiment of Foot". National Army Museum. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ Chartrand, pp. 18–19

- ^ Akins, p. 7

- ^ "Major John Pitcairn". Silverwhistle. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ "Muster for HMS Resolution during the third Pacific voyage, 1776–1780" (PDF). Captain Cook Society. 15 October 2012. p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ^ Moore, p. 41

- ^ a b c Warren Christopher (2013). "Smallpox at Sydney Cove – Who, When, Why". Journal of Australian Studies. 38: 68–86. doi:10.1080/14443058.2013.849750. S2CID 143644513.

- ^ Phillip, Arthur (1789). The Voyage of Governor Phillip To Botany Bay. Gutenberg.

- ^ Warren, Christopher, Could First Fleet smallpox infect Aborigines? – a note (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 6 November 2013, retrieved 7 March 2016,

several authors – including Josephine Flood, Alan Frost, Charles Wilson and Judy Campbell – maintain that First Fleet smallpox did not cause the outbreak

- ^ Tucker, Jedediah Stephens (1844). Admiral the Right Hon The Earl of St Vincent GCB &C. Memoirs. Vol. 2. Richard Bentley, New Burlington Street. p. 137. OCLC 6083815.

- ^ "The crest, colours, beret, nicknames and prayers of the Royal Marines". Royal Marines Museum. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ Pappalardo 2019, p. 127.

- ^ "Per Mare Per Terram – the Royal Marines 1793–1815". Napoleon Series. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ Brooks & Little, p. 86

- ^ "The Royal Marines in the War of 1812". Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ Heidler & Heidler, p. 24,56

- ^ Gleig, p. 95, 131

- ^ Nicolas, p. 232

- ^ "No. 16991". The London Gazette. 9 March 1815. pp. 440–450.

- ^ "The Battle of Fort Bowyer, Alabama". Explore Southern History. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ Chappell, pp. 14–15

- ^ a b c d "The Victoria Cross and the Royal Marines". Royal Marines Museum. Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ "Second Anglo-Chinese War ("Opium war") of 1856 – 1860 (part 2)". William Loney. Archived from the original on 3 May 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ "Class Warfare and the Selborne Scheme: The Royal Navy's battle over technology and social hierarchy". The Mariner's Mirror. 4 November 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ "Marines aboard ships" (PDF). Royal Marines Museum. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "The RMLI move to, and deployment at, Gallipoli". The Long, Long Trail. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ "No. 32846". The London Gazette. 20 July 1923. p. 4988.

- ^ "No. 32871". The London Gazette (Supplement). 16 October 1923. p. 6961.

- ^ Mountbatten, p. 107

- ^ Neillands, p. 238

- ^ "D-Day: Heroic battle in Port-en-Bessin". The Telegraph. 20 May 2009. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ Chappell, Mike (1996). Army Commandos 1940–1945. Elite Series. Vol. 64. London: Osprey Military Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-579-9.

- ^ "Operation Infatuate". Combined Operations. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ "Badge, formation, 117th Infantry Brigade, Royal Marines". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "Obituary:Colonel Ronnie Hay". The Telegraph. 24 December 2001. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ "Royal Marines World War II landing craft crews". Royal Marines History. 10 July 2021. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ Bingham, John (5 August 2008). "D-Day tanks found on seabed". The Telegraph. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ "Remembering the secret mission of Cockleshell Heroes". BBC. 31 March 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ "Britain's Sheet Anchor, Old Brothers in Arms: The 41 Independent Commando at Chosin". November 2001. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "1956: Allied Forces take control of Suez". BBC. 6 November 1956. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ French, p. 134

- ^ "The Assault on Limbang, Sarawak by 'L' Company Group, 42 Commando, Royal Marines". ARCRE. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ "The Tanganyika Army Mutiny 1964 and The BFPO Field Post Office". GB Stamp. 11 November 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ Britain's Small Wars, Northern Ireland Roll of Honour Archived 17 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 29 January 2007

- ^ "Remembering the Deal bombing". BBC. 22 September 1989. Retrieved 6 March 2007.

- ^ Henn, p. 237

- ^ "3 Commando Brigade". Naval History.net. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ Ballantyne, p. 134

- ^ "Royal Marines officers and other ranks" (PDF). Royal Navy. p. 2.

- ^ "Commando Units To Be Reshaped", Navy News, archived from the original on 11 June 2011

- ^ "Royal Marines leave Afghanistan for last time". Ministry of Defence. 9 April 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "Commandos head to Afghanistan". BBC. 18 March 2002. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ Marines, David Sharrock With the Royal (21 March 2003). "Marines spearhead the invasion with lightning attack". The Telegraph. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ "Iran releases British servicemen". BBC News. 24 June 2004. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- ^ "Handover in Helmand as 3 Cdo Brigade replace 16 Air Assault Brigade". Ministry of Defence. 9 October 2006. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "Seized sailors 'held in Tehran'". BBC. 26 March 2007. Retrieved 26 March 2007.

- ^ "No. 58774". The London Gazette (Supplement). 24 July 2008. pp. 11163–11164.

- ^ Lizzie Dearden Home Affairs Correspondent @lizziedearden (25 October 2018). "Women now allowed to apply for Royal Marines and all other frontline military roles, defence secretary announces". The Independent. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Strike from the sea – developing the UK Commando Force | Navy Lookout". www.navylookout.com. 14 June 2024. Retrieved 17 November 2024.

- ^ Douet, James, British Barracks 1600–1914, English Heritage, London 1998.

- ^ "Clarence Barracks". Sense of Place South East. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "Forton Barracks". Royal Navy Research archive. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "Royal Marines, closing of Chatham Group, Royal Marines and Royal Marine Barracks, Chatham" (PDF). Royal Marines. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "Area 2: The Royal Marine Barracks and Eastern King" (PDF). Plymouth City Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ "Cambridge Barracks Gatehouse". Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "Walmer and the Royal Marines". Walmer.web. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "Royal Marines Museum – Commandants of the Royal Marines Portsmouth Division". Memorials in Portsmouth. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ "Commandants". Memorials in Portsmouth. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "Inland Planning" (PDF). Portsmouth Society News. August 1995. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Akins, Thomas Beamish (1895). History of Halifax. Brookhouse Press. ISBN 978-1298600462.

- Ballantyne, Iain (2004). Strike From the Sea. Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1844150595.

- Brooks, Richard; Little, Matthew (2008). Tracing Your Royal Marine Ancestors: A Guide for Family Historians. Pen & Sword, Barnsley. ISBN 978-1844158690.

- Chappell, Mike (2004). Wellington's Peninsula Regiments (2): The Light Infantry. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-403-0.

- Chartrand, Rene (2002). Colonial American Troops, 1610–1774. Vol. 1. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1841763248.

- Edye, Lourenço (1893). The Historical Records of the Royal Marines. Vol. v. 1. London: Harrison & Sons.

- Francis, David (1975). The First Peninsular War: 1702–1713. Ernest Benn. ISBN 978-0510002053.

- French, David (2015). Fighting EOKA: The British Counter-Insurgency Campaign on Cyprus, 1955-1959. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198729341.

- Gleig, George Robert (1827). The campaigns of the British army at Washington and New Orleans in the years 1814-1815. John Murray, London.

- Heidler, David; Heidler, Jeanne (2004). Encyclopedia of the War of 1812. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1591143628.

- Henn, Francis (2004). Business of Some Heat: The United Nations Force in Cyprus 1972-74. Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1844150816.

- Lenihan, Padraig (2008). Consolidating Conquest, Ireland 1603–1727. Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0582772175.

- Moore, John (1989). The First Fleet Marines. University of Queensland Press. ISBN 978-0702220654.

- Mountbatten, Lord Louis (1943). Combined Operations: The Official Story of the Commandos. New York, The Macmillan Company.

- Neillands, Robin (2004). By Sea and Land: The Story of the Royal Marine Commandos. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Classics. ISBN 1-84415-043-7.

- Nicolas, Paul (1845). Historical record of the Royal marine forces. Thomas and Boone, London.

- Pappalardo, Bruno (2019). How to Survive in the Georgian Navy: A Sailor's Guide. London: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-47-283086-9.

Further reading

[edit]- A Brief Chronology of Marines History 1664-2003 (PDF). Royal Marines Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 24 September 2007.

- Blumberg, Herbert (1927). Britain's Sea Soldiers: A Record of the Royal Marines during the War 1914–1919. Devonport.

- Field, Cyril (1924). Britain's sea soldiers: a history of the Royal Marines and their predecessors and of their services in action, ashore and afloat, and upon sundry other occasions of moment. Vol. I. Liverpool: The Lyceum Press.

- Field, Cyril (1924). Britain's sea soldiers: a history of the Royal Marines and their predecessors and of their services in action, ashore and afloat, and upon sundry other occasions of moment. Vol. II. Liverpool: The Lyceum Press.

- Fraser, Edward; Carr-Laughton, L. G. (1930). The Royal Marine Artillery 1804-1923, Volume 1 [1804-1859]. London: The Royal United Services Institution. OCLC 4986867.

- Knight, H.R. (1905). Historical Records of the Buffs, East Kent Regiment, 3rd Foot, Formerly Designated the Holland Regiment. London, Medici Society.

- Neillands, Robin (1987). By Sea and Land. Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35683-6.

- Poyntz, William Henry (1892). Per Mare, Per Terram: Reminiscences of Thirty-two Years' Military, Naval, and Constabulary Service. Economic Print & Publishing Company.

- Thompson, Julian (2001). The Royal Marines, From Sea Soldiers to a Special Force. Pan Books. ISBN 978-0330377027.

- Whitefoord, Charles (1898). The Whitefoord Papers; Being the Correspondence and Other Manuscripts of Colonel Charles Whitefoord and Caleb Whitefoord, from 1739 to 1810. Clarendon press.