Henry Moore

Henry Moore | |

|---|---|

Henry Moore, photographed by Lothar Wolleh c. 1970s (detail) | |

| Born | Henry Spencer Moore |

| Nationality | English |

| Education | Leeds |

| Known for | sculpture, drawing |

| Notable work | Reclining Figures, 1930s – 1980s |

| Movement | Bronze Sculpture, Modernism |

| Awards | OM CH FBA |

Henry Spencer Moore OM CH FBA (30 July 1898 – 31 August 1986) was an English sculptor and artist. He was best known for his abstract monumental bronze sculptures which are located around the world as public works of art.

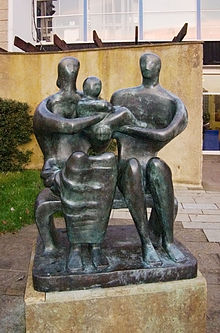

His forms are usually abstractions of the human figure, typically depicting mother-and-child or reclining figures. Moore's works are usually suggestive of the female body, apart from a phase in the 1950s when he sculpted family groups. His forms are generally pierced or contain hollow spaces. Many interpreters liken the undulating form of his reclining figures to the landscape and hills of his birthplace, Yorkshire.

Moore was born in Castleford, the son of a mining engineer. He became well-known through his larger-scale abstract cast bronze and carved marble sculptures, and was instrumental in introducing a particular form of modernism to the United Kingdom. His ability in later life to fulfil large-scale commissions made him exceptionally wealthy. Yet he lived frugally and most of the money he earned went towards endowing the Henry Moore Foundation, which continues to support education and promotion of the arts.[2]

Early life

Moore was born in Castleford, West Yorkshire, England, to Mary Baker and Raymond Spencer Moore. His mining engineer father was of Irish origin and became under-manager of the Wheldale colliery in Castleford. He was an autodidact with an interest in music and literature. Determined that his sons would not work in the mines, he saw formal education as the route to their advancement.[3] Henry was the seventh of eight children in a family that often struggled with poverty. He attended infant and elementary schools in Castleford, where he began modelling in clay and carving in wood. He decided to become a sculptor when he was eleven after hearing of Michelangelo's achievements.

The same year a teacher noticed his talent and interest in medieval sculpture and granted him a scholarship to Castleford Secondary School,[4] which several of his siblings had attended. His art teacher broadened his knowledge of art, and with her encouragement he determined to make art his career, first by sitting for examinations for a scholarship to the local art college.

Despite his early promise, Moore's parents were against him training as a sculptor, a vocation they considered manual labour with few career prospects. After a brief introduction as a student teacher, Moore became a teacher at the school he had attended. Upon turning eighteen, Moore was called to the army. He was the youngest man in the Prince of Wales's Own Civil Service Rifles regiment, and was injured in 1917 in a gas attack during the Battle of Cambrai.[5] After recovering in hospital, he saw out the remainder of the war as a physical training instructor. In stark contrast to many of his contemporaries, Moore's wartime experience was largely untroubled. He recalled later, "for me the war passed in a romantic haze of trying to be a hero."[6]

Beginnings as a sculptor

After the war Moore received an ex-serviceman's grant to continue his education, and in 1919 he became the first student of sculpture at the Leeds School of Art (now Leeds College of Art), which set up a sculpture studio especially for him. At the college, he met Barbara Hepworth—a fellow student who would also become a well-known British sculptor—and began a friendship that lasted for many years. Moore had access to many works owned by Sir Michael Sadler, the University Vice-Chancellor.[7] In 1921, Moore won a scholarship to study at the Royal College of Art in London, where his friend Hepworth had gone the year before. While in London, Moore extended his knowledge of primitive art and sculpture, studying the ethnographic collections at the Victoria and Albert Museum and the British Museum.

The early sculptures of both Moore and Hepworth follow the standard romantic Victorian style, and include natural forms, landscapes and figurative modelling of animals. Moore later became uncomfortable with classically derived ideals; his later familiarity with primitivism and the influence of sculptors such as Constantin Brancusi, Jacob Epstein and Frank Dobson led him to the method of direct carving, in which imperfections in the material and marks left by tools became part of the finished sculpture. Having adopted this technique, Moore was in conflict with academic tutors who lacked appreciation of such a modern approach. During one exercise set by Derwent Wood (the professor of sculpture at the Royal College), Moore was asked to reproduce a marble relief of Domenico Rosselli's The Virgin and Child[8] by first modelling the relief in plaster, then reproducing it in marble using the mechanical technique of "pointing". Instead, he carved the relief directly, even marking the surface to simulate the prick marks that would have been left by the pointing machine.

In 1924, Moore won a six-month travelling scholarship which he spent in Northern Italy studying the great works of Michelangelo, Giotto di Bondone, Giovanni Pisano and several other Old Masters. During this period he also visited Paris, took advantage of the timed-sketching classes at the Académie Colarossi, and viewed, in the Louvre, a plaster cast of a Toltec-Maya sculptural form, the Chac Mool. The reclining figure was to have a profound effect upon Moore's work, becoming the primary motif of his sculpture.[9]

Hampstead

On returning to London, Moore undertook a seven-year teaching post at the Royal College of Art. He was required to work two days a week, which allowed him time to spend on his own work. His first public commission, West Wind (1928–29), was one of the eight 'winds' reliefs high on the walls of London Underground's headquarters at 55 Broadway.[10] The other 'winds' were carved by contemporary sculptors including Eric Gill. In July 1929, Moore married Irina Radetsky, a painting student at the Royal College. Irina was born in Kiev in 1907 to Russian–Polish parents. Her father did not return from the Russian Revolution and her mother was evacuated to Paris where she married a British army officer. Irina was smuggled to Paris a year later and went to school there until she was 16, after which she was sent to live with her stepfather's relatives in Buckinghamshire.

Irina found security in her marriage to Moore and was soon posing for him. Shortly after they married, the couple moved to a studio in Hampstead on Parkhill Road, joining a small colony of avant-garde artists who were taking root there. Shortly afterward, Hepworth and her partner Ben Nicholson moved into a studio around the corner from Moore, while Naum Gabo, Roland Penrose and the art critic Herbert Read also lived in the area.[11] This led to a rapid cross-fertilization of ideas that Read would publicize, helping to raise Moore's public profile. The area was also a stopping-off point for many refugee architects and designers from continental Europe en route to America—many of whom would later commission works from Moore.

In 1932, Moore took up a post as the Head of the Department of Sculpture at the Chelsea School of Art.[12] Artistically, Moore, Hepworth and other members of the The Seven and Five Society would develop steadily more abstract work,[13] partly influenced by their frequent trips to Paris and their contact with leading progressive artists, notably Pablo Picasso, George Braque, Jean Arp and Alberto Giacometti. Moore flirted with Surrealism, joining Paul Nash's modern art movement, the "Unit One Group", in 1933. Moore and Nash were on the organizing committee of the London International Surrealist Exhibition, which took place in 1936. In 1937, Roland Penrose purchased an abstract 'Mother and Child' in stone from Moore that he displayed in the front garden of his house in Hampstead. The work proved controversial with other residents and the local press ran a campaign against the piece over the next two years. At this time Moore gradually transitioned from direct carving to casting in bronze, modelling preliminary maquettes in clay or plaster.

This inventive and productive period was brought to an end by the outbreak of the Second World War. The Chelsea School of Art evacuated to Northampton and Moore resigned his teaching post. During the war, Moore was commissioned as a war artist, notably producing powerful drawings of Londoners sleeping in the London Underground while sheltering from the blitz.[14] These drawings helped to boost Moore's international reputation, particularly in America. After their Hampstead home was hit by bomb shrapnel in 1940, he and Irina moved out of London to live in a farmhouse called Hoglands in the hamlet of Perry Green near Much Hadham, Hertfordshire. This was to become Moore's final home and workshop. Despite acquiring significant wealth later in life, Moore never felt the need to move to a larger home and, apart from the addition of a number of outbuildings and workshops, the house changed little.

Later years

After the war and following several earlier miscarriages, Irina gave birth to their daughter, Mary Moore, in March 1946.[15] The child was named after Moore's mother, who had died a few years earlier. Both the loss of his mother and the arrival of a baby focused Moore's mind on the family, which he expressed in his work by producing many "mother-and-child" compositions, although reclining figures also remained popular. In the same year, Moore made his first visit to America when a retrospective exhibition of his work opened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.[16] Kenneth Clark became an unlikely but influential champion of Moore's work,[17] and through his position as member of the Arts Council of Great Britain he secured exhibitions and commissions for the artist. In 1948, Moore won the International Sculpture Prize at the Venice Biennale[18] and was one of the featured artists of the Festival of Britain in 1951[19] and documenta 1 in 1955.

Toward the end of the war, Moore had been approached by educator Henry Morris, who was trying to reform education with his concept of the Village College. Morris had engaged Walter Gropius as the architect for his second village college at Impington near Cambridge, and he wanted Moore to design a major public sculpture for the site. The County Council, however, could not afford Gropius's full design, and scaled back the project when Gropius emigrated to America. Lacking funds, Morris had to cancel Moore's sculpture, which had not progressed beyond the maquette stage.[20] Moore was able to reuse the design in 1950 for a similar commission outside a secondary school for the new town of Stevenage. This time, the project was completed and Family Group became Moore's first large-scale public bronze.

In the 1950s, Moore began to receive increasingly significant commissions, including a reclining figure[21] for the UNESCO building in Paris in 1957. With many more public works of art, the scale of Moore's sculptures grew significantly and he started to employ a number of assistants to work with him at Much Hadham, including Anthony Caro[22] and Richard Wentworth.[23]

On the campus of the University of Chicago, 25 years to the minute[24] after the team of physicists led by Enrico Fermi achieved the first controlled, self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction, Moore's Nuclear Energy was unveiled on the site of what was once the university's football field bleachers, in the squash courts beneath which the experiments had taken place.[25] This 12-foot-tall piece in the middle of a large, open plaza is often thought to represent a mushroom cloud topped by a massive human skull, but Moore's interpretation was very different. He once told a friend that he hoped viewers would "go around it, looking out through the open spaces, and that they may have a feeling of being in a cathedral."[26] In Template:City-state, Moore also commemorated science with Man Enters the Cosmos (1980), which was commissioned to recognize the space exploration program.[27]

The last three decades of Moore's life continued in a similar vein; several major retrospectives took place around the world, notably a very prominent exhibition in the summer of 1972 on the grounds of the Forte di Belvedere overlooking Florence. By the end of the 1970s, there were some 40 exhibitions a year featuring his work. The number of commissions continued to increase; he completed Knife Edge – Two Piece in 1962 for College Green near the Houses of Parliament in London. According to Moore, "When I was offered the site near the House of Lords … I liked the place so much that I didn't bother to go and see an alternative site in Hyde Park — one lonely sculpture can be lost in a large park. The House of Lords site is quite different. It is next to a path where people walk and it has a few seats where they can sit and contemplate it."[28]

As his wealth grew, Moore began to worry about his legacy. With the help of his daughter Mary, he set up the Henry Moore Trust in 1972, with a view to protecting his estate from death duties. By 1977, he was paying close to a million pounds a year in income tax; to mitigate his tax burden, he established the Henry Moore Foundation as a registered charity with Irina and Mary as trustees. The Foundation was established to promote the public appreciation of art and to preserve Moore's sculptures. It now runs Moore's final home, Hoglands, as a gallery and museum of Moore's workshops.[29]

Moore turned down a knighthood in 1951 because he felt that the bestowal would lead to a perception of him as an establishment figure and that "such a title might tend to cut me off from fellow artists whose work has aims similar to mine".[30] He was awarded the Companion of Honour in 1955 and the Order of Merit in 1963. He was a trustee of both the National Gallery and Tate Gallery.[31] His proposal that a wing of the latter should be devoted to his sculptures aroused hostility among some artists. In 1975, he became the first President of the Turner Society,[32] which had been founded to campaign for a separate museum in which the whole Turner Bequest[33] might be reunited, an aim defeated by the National Gallery and Tate Gallery.

Henry Moore died on 31 August 1986, at the age of 88, in his home in Much Hadham, Hertfordshire where body is interred.

In December 2005, thieves entered the courtyard of the Henry Moore Foundation and stole a bronze statue. Closed-circuit-television footage showed that they used a crane to lower the statue onto a stolen flatbed lorry. The 1969–70 work, known as Reclining Figure LH608 is 3.6 metres long, 2 metres high by 2 metres wide, and weighs 2.1 tonnes. A substantial reward has been offered by the Foundation for information leading to its recovery. By May 2009, after a thorough investigation, British officials said they believe the work, once valued at £3 million (US$5.3 million), was probably sold for scrap metal, fetching about $3,900![34][35]

Style

The aftermath of World War II, The Holocaust, and the age of the atomic bomb instilled in the sculpture of the mid-1940s a sense that art should return to its pre-cultural and pre-rational origins. In the literature of the day, writers such as Jean-Paul Sartre advocated a similar reductive philosophy.[36] At an introductory speech in New York City for an exhibition of one of the finest modernist sculptors, Alberto Giacometti, Sartre spoke of "The beginning and the end of history".[37] Moore's sense of England emerging undefeated from siege led to his focus on pieces characterised by endurance and continuity.[36]

Moore's signature form is a reclining figure. Moore's exploration of this form, under the influence of the Toltec-Mayan figure he had seen at the Louvre, was to lead him to increasing abstraction as he turned his thoughts towards experimentation with the elements of design. Moore's earlier reclining figures deal principally with mass, while his later ones contrast the solid elements of the sculpture with the space, not only round them but generally through them as he pierced the forms with openings.

Earlier figures are pierced in a conventional manner, in which bent limbs separate from and rejoin the body. The later, more abstract figures are often penetrated by spaces directly through the body, by which means Moore explores and alternates concave and convex shapes. These more extreme piercings developed in parallel with Barbara Hepworth's sculptures.[38] Hepworth first pierced a torso after misreading a review of one of Henry Moore's early shows. The painted plaster Reclining Figure (1951) outside the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, is characteristic of Moore's later sculptures: an abstract female figure intercut with voids. There are several bronze versions of this sculpture. When Moore's niece asked why his sculptures had such simple titles, he replied, "All art should have a certain mystery and should make demands on the spectator. Giving a sculpture or a drawing too explicit a title takes away part of that mystery so that the spectator moves on to the next object, making no effort to ponder the meaning of what he has just seen. Everyone thinks that he or she looks but they don't really, you know."[39]

Moore's early work is focused on direct carving, in which the form of the sculpture evolves as the artist repeatedly whittles away at the block. In the 1930s, Moore's transition into modernism paralleled that of Barbara Hepworth; the two exchanged new ideas with each other and several other artists then living in Hampstead. Moore made many preparatory sketches and drawings for each sculpture. Most of these sketchbooks have survived and provide insight into Moore's development. He placed great importance on drawing; even when he had arthritis, he still was able to draw.[40]

After the Second World War, Moore's bronzes took on their larger scale, which was particularly suited for public art commissions. As a matter of practicality, he largely abandoned direct carving, and took on several assistants to help produce maquettes. By the end of the 1940s, he produced sculptures increasingly by modelling, working out the shape in clay or plaster before casting the final work in bronze using the lost wax technique.

At his home in Much Hadham, Moore built up a collection of natural objects; skulls, driftwood, pebbles, rocks and shells, which he would use to provide inspiration for organic forms. For his largest works, he often produced a half-scale, working model before scaling up for the final moulding and casting at a bronze foundry. Moore often refined the final full plaster shape and added surface marks before casting.[41]

Moore produced at least three significant examples of architectural sculpture during his career. In 1928, despite his own self-described "extreme reservations", he accepted his first public commission for West Wind for the London Underground Building at 55 Broadway in London, joining the company of Jacob Epstein and Eric Gill. In 1952, he completed a four-part concrete screen for the Time-Life Building in New Bond Street, London, and in 1955 Moore turned to his first and only work in carved brick, "Wall Relief no. 1" at the Bouwcentrum in Rotterdam. The brick relief was sculptured with 16,000 bricks by two Dutch bricklayers.

Legacy

Most sculptors who emerged during the height of Moore's fame, and in the aftermath of his death, found themselves cast in his shadow. By the late 1930s, Moore was a worldwide celebrity; he was the voice of British sculpture, and of British modernism in general. The next generation was constantly compared against him, and reacted by challenging his legacy, his "establishment" and his position. At the 1952 Venice Biennale, eight new British sculptors produced their Geometry of Fear works as a direct contrast to the ideals behind Moore's idea of Endurance, Continuity.[42]

Herbert Read coined the phrase for these "Young British Sculptors" when he wrote of the Biennale, "Here are images of flight, of ragged claws 'scuttling across the floors of silent seas', of excoriated flesh, frustrated sex, the geometry of fear."[43] The works alluded to rib and cage forms, insect shapes, and to aggression and predation. Read drew a direct connection and continuity between these new sculptors—all were under 40—and Moore, but in fact they were driven by a need to find a new beginning in art. Some had no formal artistic education, and, coming from a generation decimated by the war, only sought to be rid of the past.[44]

Yet Moore had a direct influence on several generations of sculptors of both British and international reputation. Among the artists who have acknowledged Moore's importance to their work are Sir Anthony Caro,[45] Phillip King[46] and Isaac Witkin,[47] all three having been assistants to Moore. Other artists whose work was influenced by him include Lynn Chadwick, Eduardo Paolozzi, Bernard Meadows, Reg Butler, William Turnbull, Robert Adams, Kenneth Armitage, and Geoffrey Clarke.[48]

Today, the Henry Moore Foundation manages the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds which supports exhibitions and research activities in international sculpture. By the Foundation's own admission, popular interest in Moore's work has declined since his death, yet the institutions he endowed continue to play an essential role in promoting contemporary art in the United Kingdom.[49]

Gallery

-

Three Way Piece No. 2 (The Archer), (1964-1965), Toronto City Hall Plaza

-

Three Piece Reclining figure No.1, (1961), Yorkshire Sculpture Park

-

Oval with Points, (1968-1970), Henry Moore Foundation

-

Hill Arches, (1972-1973), Bronze, National Gallery of Australia

-

Large Divided Oval: Butterfly (1985-1986), Kongreßhalle, Berlin

-

Draped Seated Figure at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Citations

- ^ Deaths England and Wales 1984-2006

- ^ "Chronology". Henry Moore Institute, Leeds. Retrieved on 22 September 2008.

- ^ Grohmann, 16.

- ^ Grohmann, 15.

- ^ Moore, Henry; Beckett, Jane; Russell, Fiona. "Henry Moore". Ashgate, 2003. ISBN 0-7546-0836-0

- ^ Wilkinson, Alan G. "Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations". University of California Press, 2002. 41. ISBN 0-5202-3161-9

- ^ "Henry Moore". Museum of Modern Art, 2007. Retrieved on 16 August 2008.

- ^ Allemand-Cosneau, Claude; Fath, Manfred, Mitchinson, David. "Henry Moore". Nantes: Mus'ee des Beaux Arts, 1996. 63. ISBN 3-7913-1662-1

- ^ "Henry Moore: Biography 1916-1925". Henry Moore Foundation. Retrieved on 24 September 2008.

- ^ Cork, Richard. "Art Beyond the Gallery in Early 20th Century England: In Early 20th Century England". Yale University Press, 1985. 249. ISBN 0-3000-3236-6

- ^ Read, Herbert. Henry Moore sculptor. Modernism 101. Retrieved on 22 September 2008.

- ^ Grohmann, 30.

- ^ "Seven and Five Society". Tate Britain. Retrieved on 04 September 2008.

- ^ "Insight at end of the Tunnel" Tate Modern. Retrieved on 16 August 2008.

- ^ Kuskov, Sergei. "Henry Moore". Praeger, 1973. 83. ISBN 0-8758-7054-6

- ^ Beckett et al., 96.

- ^ Beckett et al., 6.

- ^ "Henry Moore". Visual Arts Department, British Council. Retrieved on 05 September 2008.

- ^ Wilkinson, 275.

- ^ "Lot 9, Sale 1994: Family Group". Christie's, 06 May 2008. Retrieved on 04 September 2008.

- ^ "Moore, Henry". UNESCO. Retrieved on 16 August 2008.

- ^ Anthony Caro. Tate exhibition catalogue, 2005. Retrieved on 20 September 2008.

- ^ Wentworth. tate.org.uk. Retrieved on 20 September 2008.

- ^ 3:36 p.m., December 2, 1967. In: McNally, Rand. "Illinois; Guide & Gazetteer". Illinois Sesquicentennial Commission. University of Virginia, 1969. 199.

- ^ Beckett et al., 221.

- ^ Sachs, Robert G. "Henry Moore, sculptor". In "The Nuclear Chain Reaction-Forty Years Later". University of Chicago. Retrieved on 11 November 2007.

- ^ Enscripted on the plaque at the base of the sculpture.

- ^ Chamot, Mary; Farr, Dennis; Butlin, Martin. "Henry Moore". "The Modern British Paintings, drawings and Sculpture", Volume II. London: Oldbourne Press, 1964. 481. Retrieved on 05 September 2008.

- ^ Kennedy, Maev. "A hush falls over Henry Moore country". The Guardian, 22 April 1999. Retrieved on 24 September 2008.

- ^ "The Bronze Age". Tate Magazine, Issue 6, 2008. Retrieved on 23 August 2008.

- ^ Chamot, Mary; Farr, Dennis; Butlin, Martin . "Henry Moore OM, CH ". From The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, London 1964, II. Reproduced at Tate.org. Retrieved on 21 August 2008.

- ^ "J.M.W. Turner". Turner Society. Retrieved on 16 August 2008.

- ^ "Turner Collection". Tate Gallery. Retrieved on 09 August 2008.

- ^ Bowcott, Owen (19 December 2005). "Lorry used to steal £3m Moore sculpture found on housing estate". The Guardian. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "£3m Henry Moore sculpture stolen". BBC News Online. 17 December 2005. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ^ a b Causey, 34.

- ^ Morris, Frances. "Paris Post War: Art and Existentialism 1945-55". Tate Gallery, 1993. ISBN 1-8543-7124-X

- ^ "The Hole of Life". Tate Magazine, Issue 5, Autumn 2005. Retrieved on 06 September 2008.

- ^ Day, Elizabeth. "The Moore legacy". The Observer, 27 July 2008. Retrieved on 04 September 2008.

- ^ McCave, Lesley. "LA Graphic". ARTINFO, 31 July 2007. Retrieved on 16 August 2008.

- ^ "Large Arch". Bartholomew County Public Library. Retrieved on 22 September 2008.

- ^ Causey, 71.

- ^ Turner, Chris. "Henry Moore", Tate Magazine, issue 6, July/August 2003. Retrieved on 12 September 2008.

- ^ Causey, 72.

- ^ Caro biography. anthonycaro.org. Retrieved on 04 September 2008.

- ^ "Phillip King". sculpture.org.uk. Retrieved on 06 September 2008.

- ^ Isaac Witkin". The Times, 10 May 2006. Retrieved on 29 August 2008.

- ^ "The Bronze Age". Tate Magazine, Issue 6, 2008. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- ^ "Unfinished Business: Mark Wilsher on view from 26th July". Henry Moore Foundation, 2008. Retrieved on 22 September 2008.

References

- Beckett, Jane; Russell, Fiona. Henry Moore: Space, Sculpture, Politics. Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate, 2003. ISBN 0-7546-0836-0

- Causey, Andrew. Sculpture Since 1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-1928-4205-6

- Grohmann, Will. The Art of Henry Moore. New York: H.N. Abrams, 1960.

Further reading

- Hedgecoe, John. A Monumental Vision: The Sculpture of Henry Moore. Collins & Brown. ISBN 1-55670-683-9

- Henry Moore: At Dulwich Picture Gallery. Scala Publishers, 2004. ISBN 1-85759-352-9

- Kosinski, Dorothy (ed). Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century. New Haven and London: Dallas Museum of Art/Yale University Press, 2001

- O'Reilly, Sally; Oliver, Clare. Henry Moore. Scholastic Library, 2003 ISBN 0-531-16643-0

- Seldis, Henry J. Henry Moore in America. Praeger Publishers and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

- Sylvester, David. Henry Moore. Arts Council of Great Britain, London, 1968

External links

- Henry Moore Foundation—Moore Biography and chronology

- "The Enigma of Henry Moore" by Brian McAvera. Sculpture Magazine, July/August 2001: Vol. 20, No. 6.

- 3D model of Recumbent Figure (1938) from Tate

- The UNESCO Works of Art Collection

- 1898 births

- 1986 deaths

- Alumni of the Royal College of Art

- British Army personnel of World War I

- Burials at St Paul's Cathedral

- English artists

- English people of Irish descent

- English sculptors

- Erasmus Prize winners

- London Regiment soldiers

- Members of the Order of Merit

- Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour

- Modern sculptors

- People from Castleford

- People from Much Hadham

- Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class)

- War artists