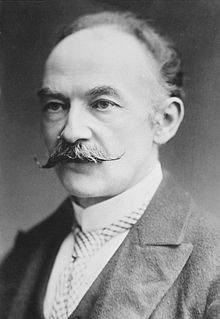

Thomas Hardy

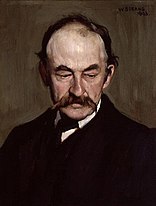

Thomas Hardy | |

|---|---|

Hardy, c. 1910–1915 | |

| Born | 2 June 1840 Stinsford, Dorset, England |

| Died | 11 January 1928 (aged 87) Dorchester, Dorset, England |

| Resting place |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Alma mater | King's College London |

| Literary movement | |

| Notable works | |

| Spouse | |

| Signature | |

| |

Thomas Hardy (2 June 1840 – 11 January 1928) was an English novelist and poet. A Victorian realist in the tradition of George Eliot, he was influenced both in his novels and in his poetry by Romanticism, including the poetry of William Wordsworth.[1] He was highly critical of much in Victorian society, especially on the declining status of rural people in Britain such as those from his native South West England.

While Hardy wrote poetry throughout his life and regarded himself primarily as a poet, his first collection was not published until 1898. Initially, he gained fame as the author of novels such as Far from the Madding Crowd (1874), The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886), Tess of the d'Urbervilles (1891) and Jude the Obscure (1895). During his lifetime, Hardy's poetry was acclaimed by younger poets (particularly the Georgians) who viewed him as a mentor. After his death his poems were lauded by Ezra Pound, W. H. Auden and Philip Larkin.[2]

Many of his novels concern tragic characters struggling against their passions and social circumstances, and they are often set in the semi-fictional region of Wessex; initially based on the medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom, Hardy's Wessex eventually came to include the counties of Dorset, Wiltshire, Somerset, Devon, Hampshire and much of Berkshire, in south-west and south central England. Two of his novels, Tess of the d'Urbervilles and Far from the Madding Crowd, were listed in the top 50 on the BBC's survey The Big Read.[3]

Life and career

[edit]Early life

[edit]

Thomas Hardy was born on 2 June 1840 in Higher Bockhampton (then Upper Bockhampton), a hamlet in the parish of Stinsford to the east of Dorchester in Dorset, England, where his father Thomas (1811–1892) worked as a stonemason and local builder. His parents had married at Melbury Osmond on 22 December 1839.[5] His mother, Jemima (née Hand; 1813–1904),[6] was well read, and she educated Thomas until he went to his first school at Bockhampton at the age of eight. For several years he attended Mr. Last's Academy for Young Gentlemen in Dorchester, where he learned Latin and demonstrated academic potential.[7]

Because Hardy's family lacked the means for a university education, his formal education ended at the age of sixteen, when he became apprenticed to James Hicks, a local architect.[8] He worked on the design of the new church at nearby Athelhampton, situated just opposite Athelhampton House where he painted a watercolour of the Tudor gatehouse while visiting his father, who was repairing the masonry of the dovecote.

He moved to London in 1862 where he enrolled as a student at King's College London. He won prizes from the Royal Institute of British Architects and the Architectural Association. He joined Arthur Blomfield's practice as assistant architect in April 1862 and worked with Blomfield on Christ Church, East Sheen Richmond, London where the tower collapsed in 1863, and All Saints' parish church in Windsor, Berkshire, in 1862–64. A reredos, possibly designed by Hardy, was discovered behind panelling at All Saints' in August 2016.[9][10] In the mid-1860s, Hardy was in charge of the excavation of part of the graveyard of St Pancras Old Church before its destruction when the Midland Railway was extended to a new terminus at St Pancras.[11]

Hardy never felt at home in London, because he was acutely conscious of class divisions and his own feelings of social inferiority. During this time he became interested in social reform and the works of John Stuart Mill. He was introduced by his Dorset friend Horace Moule to the works of Charles Fourier and Auguste Comte. Mill's essay On Liberty was one of Hardy's cures for despair, and in 1924 he declared that "my pages show harmony of view with" Mill.[12] He was also attracted to Matthew Arnold's and Leslie Stephen's ideal of the urbane liberal freethinker.[13]

After five years, concerned about his health, he returned to Dorset, settling in Weymouth, and decided to dedicate himself to writing.

Personal

[edit]

In 1870, while on an architectural mission to restore the parish church of St Juliot in Cornwall,[14] Hardy met and fell in love with Emma Gifford, whom he married on 17 September 1874, at St Peter's Church, Paddington, London.[15][16][17][18] The couple rented St David's Villa, Southborough (now Surbiton) for a year. In 1885 Thomas and his wife moved into Max Gate in Dorchester, a house designed by Hardy and built by his brother. Although they became estranged, Emma's death in 1912 had a traumatic effect on him and Hardy made a trip to Cornwall after her death to revisit places linked with their courtship; his Poems 1912–13 reflect upon her death. In 1914, Hardy married his secretary Florence Emily Dugdale, who was 39 years his junior. He remained preoccupied with his first wife's death and tried to overcome his remorse by writing poetry.

In his later years, he kept a Wire Fox Terrier named Wessex, who was notoriously ill-tempered. Wessex's grave stone can be found on the Max Gate grounds.[19][20]

In 1910, Hardy had been appointed a Member of the Order of Merit and was also for the first time nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature. He was nominated again for the prize 11 years later and received a total of 25 nominations until 1927.[21][22] He was at least once, in 1923, one of the final candidates for the prize, but was not awarded.[23]

Hardy and the theatre

[edit]Hardy's interest in the theatre dated from the 1860s. He corresponded with various would-be adapters over the years, including Robert Louis Stevenson in 1886 and Jack Grein and Charles Jarvis in the same decade.[24] Neither adaptation came to fruition, but Hardy showed he was potentially enthusiastic about such a project. One play that was performed, however, caused him a certain amount of pain. His experience of the controversy and lukewarm critical reception that had surrounded his and Comyns Carr's adaptation of Far from the Madding Crowd in 1882 left him wary of the damage that adaptations could do to his literary reputation. So, in 1908, he so readily and enthusiastically became involved with a local amateur group, at the time known as the Dorchester Dramatic and Debating Society, but that would become the Hardy Players. His reservations about adaptations of his novels meant he was initially at some pains to disguise his involvement in the play.[25] However, the international success[26] of the play, The Trumpet Major, led to a long and successful collaboration between Hardy and the Players over the remaining years of his life. Indeed, his play The Famous Tragedy of the Queen of Cornwall at Tintagel in Lyonnesse (1923) was written to be performed by the Hardy Players.[27]

Later years

[edit]

From the 1880s, Hardy became increasingly involved in campaigns to save ancient buildings from destruction, or destructive modernisation, and he became an early member of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. His correspondence refers to his unsuccessful efforts to prevent major alterations to the parish church at Puddletown, close to his home at Max Gate. He became a frequent visitor at Athelhampton House, which he knew from his teenage years, and in his letters he encouraged the owner, Alfred Cart de Lafontaine, to conduct the restoration of that building in a sensitive way.

In 1914, Hardy was one of 53 leading British authors—including H. G. Wells, Rudyard Kipling and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle—who signed their names to the "Authors' Declaration", justifying Britain's involvement in the First World War. This manifesto declared that the German invasion of Belgium had been a brutal crime, and that Britain "could not without dishonour have refused to take part in the present war."[28] Hardy was horrified by the destruction caused by the war, pondering that "I do not think a world in which such fiendishness is possible to be worth the saving" and "better to let western 'civilization' perish, and let the black and yellow races have a chance."[29] He wrote to John Galsworthy that "the exchange of international thought is the only possible salvation for the world."[29]

Shortly after helping to excavate the Fordington mosaic, Hardy became ill with pleurisy in December 1927 and died at Max Gate just after 9 pm on 11 January 1928, having dictated his final poem to his wife on his deathbed; the cause of death was cited, on his death certificate, as "cardiac syncope", with "old age" given as a contributory factor. His funeral was on 16 January at Westminster Abbey, and it proved a controversial occasion because Hardy had wished for his body to be interred at Stinsford in the same grave as his first wife, Emma. His family and friends concurred; however, his executor, Sir Sydney Carlyle Cockerell, insisted that he be placed in the abbey's famous Poets' Corner. A compromise was reached whereby his heart was buried at Stinsford with Emma, and his ashes in Poets' Corner.[30] Hardy's estate at death was valued at £95,418 (equivalent to £7,300,000 in 2023).[31]

Shortly after Hardy's death, the executors of his estate burnt his letters and notebooks, but twelve notebooks survived, one of them containing notes and extracts of newspaper stories from the 1820s, and research into these has provided insight into how Hardy used them in his works. The opening chapter of The Mayor of Casterbridge, for example, written in 1886, was based on press reports of wife-selling.[32] In the year of his death Mrs Hardy published The Early Life of Thomas Hardy, 1841–1891, compiled largely from contemporary notes, letters, diaries and biographical memoranda, as well as from oral information in conversations extending over many years.

Hardy's work was admired by many younger writers, including D. H. Lawrence,[33] John Cowper Powys and Virginia Woolf.[34] In his autobiography Good-Bye to All That (1929), Robert Graves recalls meeting Hardy in Dorset in the early 1920s and how Hardy received him and his new wife warmly, and was encouraging about his work.

Hardy's birthplace in Bockhampton and his house Max Gate, both in Dorchester, are owned by the National Trust.

Novels

[edit]

Hardy's first novel, The Poor Man and the Lady, finished by 1867, failed to find a publisher. He then showed it to his mentor and friend, the Victorian poet and novelist George Meredith, who felt that The Poor Man and the Lady would be too politically controversial and might damage Hardy's ability to publish in the future. So Hardy followed his advice and he did not try further to publish it. He subsequently destroyed the manuscript, but used some of the ideas in his later work.[35] In his recollections in Life and Work, Hardy described the book as "socialistic, not to say revolutionary; yet not argumentatively so."[36]

After he abandoned his first novel, Hardy wrote two new ones that he hoped would have more commercial appeal, Desperate Remedies (1871) and Under the Greenwood Tree (1872), both of which were published anonymously; it was while working on the latter that he met Emma Gifford, who would become his wife.[35] In 1873 A Pair of Blue Eyes, a novel drawing on Hardy's courtship of Emma, was published under his own name. A plot device popularised by Charles Dickens, the term "cliffhanger" is considered to have originated with the serialised version of A Pair of Blue Eyes (published in Tinsley's Magazine between September 1872 and July 1873) in which Henry Knight, one of the protagonists, is left literally hanging off a cliff.[37][38] Elements of Hardy's fiction reflect the influence of the commercially successful sensation fiction of the 1860s, particularly the legal complications in novels such as Desperate Remedies (1871), Far from the Madding Crowd (1874) and Two on a Tower (1882).[39]

In Far from the Madding Crowd, Hardy first introduced the idea of calling the region in the west of England, where his novels are set, Wessex. Wessex had been the name of an early Saxon kingdom, in approximately the same part of England. Far from the Madding Crowd was successful enough for Hardy to give up architectural work and pursue a literary career. Over the next 25 years, Hardy produced 10 more novels.

Subsequently, Hardy moved from London to Yeovil, and then to Sturminster Newton, where he wrote The Hand of Ethelberta (1876) and The Return of the Native (1878).[40] In 1880, Hardy published his only historical novel, The Trumpet-Major. The next year, in 1881, A Laodicean was published. A further move to Wimborne saw Hardy write Two on a Tower, published in 1882, a romance story set in the world of astronomy. Then in 1885, they moved for the last time, to Max Gate, a house outside Dorchester designed by Hardy and built by his brother. There he wrote The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886), The Woodlanders (1887) and Tess of the d'Urbervilles (1891), the last of which attracted criticism for its sympathetic portrayal of a "fallen woman", and initially it was refused publication. Its subtitle, A Pure Woman: Faithfully Presented, was intended to raise the eyebrows of the Victorian middle classes.

Jude the Obscure, published in 1895, was the last novel written by Hardy. It was met with an even stronger negative response from the Victorian public because of its controversial treatment of sex, religion and marriage. Its apparent attack on the institution of marriage caused strain on Hardy's already difficult marriage because Emma Hardy was concerned that Jude the Obscure would be read as autobiographical. Some booksellers sold the novel in brown paper bags, and Walsham How, the Bishop of Wakefield, is reputed to have burnt his copy.[32] In his postscript of 1912, Hardy humorously referred to this incident as part of the career of the book: "After these [hostile] verdicts from the press its next misfortune was to be burnt by a bishop – probably in his despair at not being able to burn me".[41] Despite this, Hardy had become a celebrity by the 1900s, but some argue that he gave up writing novels because of the criticism of both Tess of the d'Urbervilles and Jude the Obscure.[42] However, in a March 1928 piece in the Bookman that posthumously printed interviews with Hardy, he is quoted as saying that, in addition to the negative publicity, he chose to stop writing novels because "I never cared very much about writing novels" and "I had written quite enough novels."[43]

The Well-Beloved, first serialised in 1892 and written before Jude the Obscure, was the last of Hardy's fourteen novels to be published, in 1897.

Literary themes

[edit]Considered a Victorian realist, Hardy examines the social constraints on the lives of those living in Victorian England, and criticises those beliefs, especially those relating to marriage, education and religion, that limited people's lives and caused unhappiness. Such unhappiness, and the suffering it brings, is seen by poet Philip Larkin as central in Hardy's works:

What is the intensely maturing experience of which Hardy's modern man is most sensible? In my view it is suffering, or sadness, and extended consideration of the centrality of suffering in Hardy's work should be the first duty of the true critic for which the work is still waiting [...] Any approach to his work, as to any writer's work, must seek first of all to determine what element is peculiarly his, which imaginative note he strikes most plangently, and to deny that in this case it is the sometimes gentle, sometimes ironic, sometimes bitter but always passive apprehension of suffering is, I think, wrong-headed.[44]

In Two on a Tower, for example, Hardy takes a stand against these rules of society with a story of love that crosses the boundaries of class. The reader is forced to reconsider the conventions set up by society for the relationships between men and women. Nineteenth-century society had conventions, which were enforced. In this novel Swithin St Cleeve's idealism pits him against such contemporary social constraints.

In a novel structured around contrasts, the main opposition is between Swithin St Cleeve and Lady Viviette Constantine, who are presented as binary figures in a series of ways: aristocratic and lower class, youthful and mature, single and married, fair and dark, religious and agnostic...she [Lady Viviette Constantine] is also deeply conventional, absurdly wishing to conceal their marriage until Swithin has achieved social status through his scientific work, which gives rise to uncontrolled ironies and tragic-comic misunderstandings.[45]

Fate or chance is another important theme. Hardy's characters often encounter crossroads on a journey, a junction that offers alternative physical destinations but which is also symbolic of a point of opportunity and transition, further suggesting that fate is at work. Far from the Madding Crowd is an example of a novel in which chance has a major role: "Had Bathsheba not sent the valentine, had Fanny not missed her wedding, for example, the story would have taken an entirely different path."[46] Indeed, Hardy's main characters often seem to be held in fate's overwhelming grip.

Poetry

[edit]

In 1898, Hardy published his first volume of poetry, Wessex Poems, a collection of poems written over 30 years. While some suggest that Hardy gave up writing novels following the harsh criticism of Jude the Obscure in 1896, the poet C. H. Sisson calls this "hypothesis" "superficial and absurd".[42][47] In the twentieth century Hardy published only poetry.

Thomas Hardy published Poems of the Past and the Present in 1901, which contains "The Darkling Thrush" (originally titled "The Century's End"), one of his best known poems about the turn of the century.[48]

Thomas Hardy wrote in a great variety of poetic forms, including lyrics, ballads, satire, dramatic monologues and dialogue, as well as a three-volume epic closet drama The Dynasts (1904–08),[49] and though in some ways a very traditional poet, because he was influenced by folksong and ballads,[50] he "was never conventional," and "persistently experiment[ed] with different, often invented, stanza forms and metres,"[51] and made use of "rough-hewn rhythms and colloquial diction".[52]

Hardy wrote a number of significant war poems that relate to both the Boer Wars and World War I, including "Drummer Hodge", "In Time of 'The Breaking of Nations'" and "The Man He Killed"; his work had a profound influence on other war poets such as Rupert Brooke and Siegfried Sassoon.[53] Hardy in these poems often used the viewpoint of ordinary soldiers and their colloquial speech.[53] A theme in the Wessex Poems is the long shadow that the Napoleonic Wars cast over the 19th century, as seen, for example, in "The Sergeant's Song" and "Leipzig".[54] The Napoleonic War is the subject of The Dynasts.

Some of Hardy's more famous poems are from Poems 1912–13, which later became part of Satires of Circumstance (1914), written following the death of his wife Emma in 1912. They had been estranged for 20 years, and these lyric poems express deeply felt "regret and remorse".[53] Poems like "After a Journey", "The Voice" and others from this collection "are by general consent regarded as the peak of his poetic achievement".[49] In a 2007 biography on Hardy, Claire Tomalin argues that Hardy became a truly great English poet after the death of his first wife Emma, beginning with these elegies, which she describes as among "the finest and strangest celebrations of the dead in English poetry."[55]

Many of Hardy's poems deal with themes of disappointment in love and life, and "the perversity of fate", presenting these themes with "a carefully controlled elegiac feeling".[56] Irony is an important element in a number of Hardy's poems, including "The Man He Killed" and "Are You Digging on My Grave".[54] A few of Hardy's poems, such as "The Blinded Bird", a melancholy polemic against the sport of vinkenzetting, reflect his firm stance against animal cruelty, exhibited in his antivivisectionist views and his membership in the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.[57]

Although his poems were initially not as well received as his novels had been, Hardy is now recognised as one of the great poets of the 20th century, and his verse had a profound influence on later writers, including Robert Frost, W. H. Auden, Dylan Thomas and Philip Larkin.[52] Larkin included 27 poems by Hardy compared with only nine by T. S. Eliot in his edition of The Oxford Book of Twentieth Century English Verse in 1973.[58] There were fewer poems by W. B. Yeats.[59] Poet-critic Donald Davie's Thomas Hardy and English Poetry considers Hardy's contribution to ongoing poetic tradition at length and in creative depth. Davie's friend Thom Gunn also wrote on Hardy and acknowledged his stature and example.

Religious beliefs

[edit]

Hardy's family was Anglican, but not especially devout. He was baptised at the age of five weeks and attended church, where his father and uncle contributed to music. He did not attend the local Church of England school, instead being sent to Mr Last's school, three miles away. As a young adult, he befriended Henry R. Bastow (a Plymouth Brethren man), who also worked as a pupil architect, and who was preparing for adult baptism in the Baptist Church. Hardy flirted with conversion, but decided against it.[60] Bastow went to Australia and maintained a long correspondence with Hardy, but eventually Hardy tired of these exchanges and the correspondence ceased. This concluded Hardy's links with the Baptists.

The irony and struggles of life, coupled with his naturally curious mind, led him to question the traditional Christian view of God:

The Christian God – the external personality – has been replaced by the intelligence of the First Cause...the replacement of the old concept of God as all-powerful by a new concept of universal consciousness. The 'tribal god, man-shaped, fiery-faced and tyrannous' is replaced by the 'unconscious will of the Universe' which progressively grows aware of itself and 'ultimately, it is to be hoped, sympathetic'.[61]

Scholars have debated Hardy's religious leanings for years, often unable to reach a consensus. Once, when asked in correspondence by a clergyman, Dr. A. B. Grosart, about the question of reconciling the horrors of human and animal life with "the absolute goodness and non-limitation of God",[62] Hardy replied,

Mr. Hardy regrets that he is unable to offer any hypothesis which would reconcile the existence of such evils as Dr. Grosart describes with the idea of omnipotent goodness. Perhaps Dr. Grosart might be helped to a provisional view of the universe by the recently published Life of Darwin and the works of Herbert Spencer and other agnostics.[63]

Hardy frequently conceived of, and wrote about, supernatural forces, particularly those that control the universe through indifference or caprice, a force he called The Immanent Will. He also showed in his writing some degree of fascination with ghosts and spirits.[63] Even so, he retained a strong emotional attachment to the Christian liturgy and church rituals, particularly as manifested in rural communities, that had been such a formative influence in his early years, and Biblical references can be found woven throughout many of Hardy's novels. Hardy's friends during his apprenticeship to John Hicks included Horace Moule (one of the eight sons of Henry Moule) and the poet William Barnes, both ministers of religion. Moule remained a close friend of Hardy's for the rest of his life, and introduced him to new scientific findings that cast doubt on literal interpretations of the Bible,[64] such as those of Gideon Mantell. Moule gave Hardy a copy of Mantell's book The Wonders of Geology (1848) in 1858, and Adelene Buckland has suggested that there are "compelling similarities" between the "cliffhanger" section from A Pair of Blue Eyes and Mantell's geological descriptions. It has also been suggested that the character of Henry Knight in A Pair of Blue Eyes was based on Horace Moule.[65]

Throughout his life, Hardy sought a rationale for believing in an afterlife or a timeless existence, turning first to spiritualists, such as Henri Bergson, and then to Albert Einstein and J. M. E. McTaggart, considering their philosophy on time and space in relation to immortality.[66]

Locations in novels

[edit]Sites associated with Hardy's own life and which inspired the settings of his novels continue to attract literary tourists and casual visitors. For locations in Hardy's novels see: Thomas Hardy's Wessex, and the Thomas Hardy's Wessex[67] research site, which includes maps.[68]

Influence

[edit]Hardy corresponded with and visited Lady Catherine Milnes Gaskell at Wenlock Abbey and many of Lady Catherine's books are inspired by Hardy, who was very fond of her.[69]

D. H. Lawrence's Study of Thomas Hardy (1914, first published 1936) indicates the importance of Hardy for him, even though this work is a platform for Lawrence's own developing philosophy rather than a more standard literary study. The influence of Hardy's treatment of character, and Lawrence's own response to the central metaphysic behind many of Hardy's novels, helped significantly in the development of The Rainbow (1915) and Women in Love (1920).[70]

Wood and Stone (1915), the first novel by John Cowper Powys, who was a contemporary of Lawrence, was "Dedicated with devoted admiration to the greatest poet and novelist of our age Thomas Hardy".[71] Powys's later novel Maiden Castle (1936) is set in Dorchester, which was Hardy's Casterbridge, and was intended by Powys to be a "rival" to Hardy's The Mayor of Casterbridge.[72] Maiden Castle is the last of Powys's so-called Wessex novels, Wolf Solent (1929), A Glastonbury Romance (1932) and Weymouth Sands (1934), which are set in Somerset and Dorset.[73]

Hardy was clearly the starting point for the character of the novelist Edward Driffield in W. Somerset Maugham's novel Cakes and Ale (1930).[74] Thomas Hardy's works also feature prominently in the American playwright Christopher Durang's The Marriage of Bette and Boo (1985), in which a graduate thesis analysing Tess of the d'Urbervilles is interspersed with analysis of Matt's family's neuroses.[75]

Musical settings

[edit]A number of notable English composers, including Gerald Finzi,[76][77] Benjamin Britten,[78] Ralph Vaughan Williams[79] and Gustav Holst[80] set poems by Hardy to music. Others include Holst's daughter Imogen Holst, John Ireland,[81] Muriel Herbert, Ivor Gurney and Robin Milford.[82] Orchestral tone poems which evoke the landscape of Hardy's novels include Ireland's Mai-Dun (1921) and Holst's Egdon Heath: A Homage to Thomas Hardy (1927).

Hardy has been a significant influence on Nigel Blackwell, frontman of the post-punk British rock band Half Man Half Biscuit, who has often incorporated phrases (some obscure) by or about Hardy into his song lyrics.[83][84]

Works

[edit]Prose

[edit]

In 1912, Hardy divided his novels and collected short stories into three classes:[85]

Novels of character and environment

[edit]- The Poor Man and the Lady (1867, unpublished and lost)

- Under the Greenwood Tree: A Rural Painting of the Dutch School (1872)

- Far from the Madding Crowd (1874)

- The Return of the Native (1878)

- The Mayor of Casterbridge: The Life and Death of a Man of Character (1886)

- The Woodlanders (1887)

- Wessex Tales (1888, a collection of short stories)

- Tess of the d'Urbervilles: A Pure Woman Faithfully Presented (1891)

- Life's Little Ironies (1894, a collection of short stories)

- Jude the Obscure (1895)

Romances and fantasies

[edit]- A Pair of Blue Eyes: A Novel (1873)

- The Trumpet-Major (1880)

- Two on a Tower: A Romance (1882)

- A Group of Noble Dames (1891, a collection of short stories)

- The Well-Beloved: A Sketch of a Temperament (1897) (first published as a serial from 1892)

Novels of ingenuity

[edit]- Desperate Remedies: A Novel (1871)

- The Hand of Ethelberta: A Comedy in Chapters (1876)

- A Laodicean: A Story of To-day (1881)

Other

[edit]Hardy also produced minor tales; one story, The Spectre of the Real (1894) was written in collaboration with Florence Henniker.[86] An additional short-story collection, beyond the ones mentioned above, is A Changed Man and Other Tales (1913). His works have been collected as the 24-volume Wessex Edition (1912–13) and the 37-volume Mellstock Edition (1919–20). His largely self-written biography appears under his second wife's name in two volumes from 1928 to 1930, as The Early Life of Thomas Hardy, 1840–91 and The Later Years of Thomas Hardy, 1892–1928, now published in a critical one-volume edition as The Life and Work of Thomas Hardy, edited by Michael Millgate (1984).

Short stories

[edit](with date of first publication)

- "How I Built Myself a House" (1865)

- "Destiny and a Blue Cloak" (1874)

- "The Thieves Who Couldn't Stop Sneezing" (1877)

- "The Duchess of Hamptonshire" (1878) (collected in A Group of Noble Dames)

- "The Distracted Preacher" (1879) (collected in Wessex Tales)

- "Fellow-Townsmen" (1880) (collected in Wessex Tales)

- "The Honourable Laura" (1881) (collected in A Group of Noble Dames)

- "What the Shepherd Saw" (1881) (collected in A Changed Man and Other Stories)

- "A Tradition of Eighteen Hundred and Four" (1882) (collected in Life's Little Ironies)

- "The Three Strangers" (1883) (collected in Wessex Tales)

- "The Romantic Adventures of a Milkmaid" (1883) (collected in A Changed Man and Other Stories)

- "Interlopers at the Knap" (1884) (collected in Wessex Tales)

- "A Mere Interlude" (1885) (collected in A Changed Man and Other Stories)

- "A Tryst at an Ancient Earthwork" (1885) (collected in A Changed Man and Other Stories)

- "Alicia's Diary" (1887) (collected in A Changed Man and Other Stories)

- "The Waiting Supper" (1887–88) (collected in A Changed Man and Other Stories)

- "The Withered Arm" (1888) (collected in Wessex Tales)

- "A Tragedy of Two Ambitions" (1888) (collected in Life's Little Ironies)

- "The First Countess of Wessex" (1889) (collected in A Group of Noble Dames)

- "Anna, Lady Baxby" (1890) (collected in A Group of Noble Dames)

- "The Lady Icenway" (1890) (collected in A Group of Noble Dames)

- "Lady Mottisfont" (1890) (collected in A Group of Noble Dames)

- "The Lady Penelope" (1890) (collected in A Group of Noble Dames)

- "The Marchioness of Stonehenge" (1890) (collected in A Group of Noble Dames)

- "Squire Petrick's Lady" (1890) (collected in A Group of Noble Dames)

- "Barbara of the House of Grebe" (1890) (collected in A Group of Noble Dames)

- "The Melancholy Hussar of The German Legion" (1890) (collected in Life's Little Ironies)

- "Absent-Mindedness in a Parish Choir" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies)

- "The Winters and the Palmleys" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies)

- "For Conscience' Sake" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies)

- "Incident in the Life of Mr. George Crookhill" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies)

- "The Doctor's Legend" (1891)

- "Andrey Satchel and the Parson and Clerk" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies)

- "The History of the Hardcomes" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies)

- "Netty Sargent's Copyhold" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies)

- "On the Western Circuit" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies)

- "A Few Crusted Characters: Introduction" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies)

- "The Superstitious Man's Story" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies)

- "Tony Kytes, the Arch-Deceiver" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies)

- "To Please His Wife" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies)

- "The Son's Veto" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies)

- "Old Andrey's Experience as a Musician" (1891) (collected in Life's Little Ironies)

- "Our Exploits At West Poley" (1892–93)

- "Master John Horseleigh, Knight" (1893) (collected in A Changed Man and Other Stories)

- "The Fiddler of the Reels" (1893) (collected in Life's Little Ironies)

- "An Imaginative Woman" (1894) (collected in Wessex Tales, 1896 edition)

- "The Spectre of the Real" (1894)

- "A Committee-Man of 'The Terror'" (1896) (collected in A Changed Man and Other Stories)

- "The Duke's Reappearance" (1896) (collected in A Changed Man and Other Stories)

- "The Grave by the Handpost" (1897) (collected in A Changed Man and Other Stories)

- "A Changed Man" (1900) (collected in A Changed Man and Other Stories)

- "Enter a Dragoon" (1900) (collected in A Changed Man and Other Stories)

- "Blue Jimmy: The Horse Stealer" (1911)

- "Old Mrs. Chundle" (1929)

- "The Unconquerable"(1992)

Poetry collections

[edit]- Wessex Poems and Other Verses (1898)

- Poems of the Past and the Present (1901)

- Time's Laughingstocks and Other Verses (1909)

- Satires of Circumstance (1914)

- Moments of Vision (1917)

- Collected Poems (1919)

- Late Lyrics and Earlier with Many Other Verses (1922)

- Human Shows, Far Phantasies, Songs and Trifles (1925)

- Winter Words in Various Moods and Metres (1928)

- The Complete Poems (Macmillan, 1976)

- Selected Poems (Edited by Harry Thomas, Penguin, 1993)

- Hardy: Poems (Everyman's Library Pocket Poets, 1995)

- Thomas Hardy: Selected Poetry and Nonfictional Prose (St. Martin's Press, 1996)

- Selected Poems (Edited by Robert Mezey, Penguin, 1998)

- Thomas Hardy: The Complete Poems (Edited by James Gibson, Palgrave, 2001)

Online poems: Poems by Thomas Hardy[87] at Poetry Foundation and Poems by Thomas Hardy at poemhunter.com[88]

Drama

[edit]- The Dynasts: An Epic-Drama of the War with Napoleon (verse drama)

- The Dynasts, Part 1 (1904)

- The Dynasts, Part 2 (1906)

- The Dynasts, Part 3 (1908)

- The Famous Tragedy of the Queen of Cornwall at Tintagel in Lyonnesse (1923) (one-act play)

References

[edit]- ^ Taylor, Dennis (Winter 1986), "Hardy and Wordsworth", Victorian Poetry, 24 (4).

- ^ Watts, Cedric (2007). Thomas Hardy: 'Tess of the d'Urbervilles'. Humanities-Ebooks. pp. 13, 14.

- ^ "BBC – The Big Read" Archived 31 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. BBC. April 2003, Retrieved 16 December 2016

- ^ Brown, Matt (28 December 2022). "The Hardy Tree Of St Pancras Has Fallen". Londonist. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ Copy of marriage certificate in Melbury Osmond parish church.

- ^ "Thomas Hardy: The Time-Torn Man". The Guardian. 13 October 2006. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Tomalin, Claire (2007), Thomas Hardy: the Time-torn Man, Penguin, pp. 30, 36.

- ^ Walsh, Lauren (2005), "Introduction", The Return of the Native, by Thomas Hardy (print), Classics, New York: Barnes & Noble.

- ^ Flood, Alison (16 August 2016). "Thomas Hardy altarpiece discovered in Windsor church". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ^ "Legendary author Thomas Hardy's lost contribution to Windsor church uncovered". Royal Borough Observer. 15 August 2016. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ^ Burley, Peter (2012). "When steam railroaded history". Cornerstone. 33 (1): 9.

- ^ Wilson, Keith (2009). A Companion to Thomas Hardy. John Wiley & Sons. p. 55.

- ^ Widdowson, Peter (2004). Thomas Hardy and Contemporary Literary Studies. Springer. p. 132.

- ^ Gibson, James (ed.) (1975) Chosen Poems of Thomas Hardy, London: Macmillan Education; p.9.

- ^ Michael Millgate, ‘Hardy, Thomas (1840–1928)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2006 accessed 7 Feb 2016

- ^ "FreeBMD Home Page". freebmd.org.uk. Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ Hardy, Emma (1961) Some Recollections by Emma Hardy; with some relevant poems by Thomas Hardy; ed. by Evelyn Hardy & R. Gittings. London: Oxford University Press

- ^ "Thomas Hardy – the Time-Torn Man" (a reading of Claire Tomalin's book of the same name), BBC Radio 4, 23 October 2006

- ^ “At home with the wizard” Archived 17 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian, Retrieved 10 July 2019

- ^ "Wiltshire Days Out – Thomas Hardy at Stourhead". BBC. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ "No. 28393". The London Gazette. 8 July 1910. p. 4857.

- ^ "Nomination Database". April 2020. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ Asaid, Alan (11 December 2012). "Yeats och Nobelpriset" (in Swedish). kulturdelen.com.

- ^ Wilson, Keith (1995). Thomas Hardy on Stage. The Macmillan Press. p. 29. ISBN 9780333598856.

- ^ Wilson, Keith (1995). Thomas Hardy on Stage. The Macmillan Press. p. 60. ISBN 9780333598856

- ^ Evans, Harold (1908). "A Souvenir of the Performances of the Play adapted from Mr. Thos. Hardy's Novel 'The Trumpet Major'". The Dorchester Debating and Dramatic Society.

- ^ Dean, Andrew R (February 1993). "The Sources of The Famous Tragedy of the Queen of Cornwall". Thomas Hardy Journal, the. 9 (1): 76–89. JSTOR 45274094.

- ^ "1914 Authors' Manifesto Defending Britain's Involvement in WWI, Signed by H.G. Wells and Arthur Conan Doyle". Slate. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ a b Sherman, George William (1976). The Pessimism of Thomas Hardy. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 447.

- ^ Bradford, Charles Angell (1933). Heart Burial. London: Allen & Unwin. p. 246. ISBN 978-1-162-77181-6.

- ^ From Probate Index for 1928: "Hardy O. M. Thomas of Max Gate Dorchester Dorsetshire died 11 January 1928 Probate London 22 February to Lloyds Bank Limited Effects £90707 14s 3d Resworn £95418 3s 1d."

- ^ a b "Homeground: Dead man talking". BBC Online. 20 August 2003. Archived from the original on 31 August 2004. Retrieved 12 August 2006.

- ^ Steele, Bruce, ed. (1985) [1914], "Literary criticism and metaphysics", Study of Thomas Hardy and other essays, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-25252-0.

- ^ "The Novels of Thomas Hardy", The Common Reader, 2nd series.

- ^ a b J. B. Bullen (2013). Thomas Hardy: The World of his Novels. Frances Lincoln. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-78101-122-5.

- ^ Widdowson, Peter (2018). Thomas Hardy. Oxford University Press. p. 27.

- ^ Thomas Hardy (2013). Delphi Complete Works of Thomas Hardy (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. pp. 570–. ISBN 978-1-908909-17-6. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ Emily Nussbaum. "The curious staying power of the cliffhanger". The New Yorker. 10 July 2019.

- ^ Trish Ferguson, Thomas Hardy's Legal Fictions, Edinburgh University Press, 2013.

- ^ "Curiosities of Sturminster Newton – Dorset Life – The Dorset Magazine". dorsetlife.co.uk. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ Hardy, Thomas (1998). Jude the Obscure. Penguin Classics. p. 466. ISBN 0-14-043538-7. Archived from the original on 15 September 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Thomas Hardy", The Norton Anthology of English Literature, 7th edition, vol. 2. New York: W.W. Norton, 2000, p.1916.

- ^ "Talks with Thomas Hardy". Bookman Publishing Co. March 1928. Retrieved 14 December 2024.

- ^ Larkin, Philip 1983, "Wanted: Good Hardy Critic" in Required Writing, London: Faber and Faber.

- ^ Geoffrey Harvey, Thomas Hardy: The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy. New York: Routledge, 2003, p.108.

- ^ "Far from the Madding Crowd, Thomas Hardy – Introduction (Twentieth-Century Literary Criticism. Ed. Linda Pavlovski. Vol. 153. Gale Group, Inc.)". Enotes.com. Archived from the original on 15 January 2010. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ^ "Introduction" to the Penguin edition of Jude the Obscure (1978). Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1984, p.13.

- ^ Rumens, Carol (28 December 2009). "Poem of the week: The Darkling Thrush, by Thomas Hardy". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Thomas Hardy (British writer) – Encyclopædia Britannica". Britannica.com. 6 November 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ "Thomas Hardy", The Bloomsbury Guide to English Literature, ed. Marion Wynne Davies. New York: Prentice Hall, 1990, p.583.

- ^ The Bloomsbury Guide, p. 583.

- ^ a b "Thomas Hardy | Academy of American Poets". Poets.org. 11 January 1928. Archived from the original on 14 April 2014. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ a b c Axelrod, Jeremy. "Thomas Hardy". The Poetry Foundation. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ a b Katherine Kearney Maynard, Thomas Hardy's Tragic Poetry: The Lyrics and The Dynasts. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1991, pp. 8–12.

- ^ Tomalin, Claire. "Thomas Hardy." New York: Penguin, 2007.

- ^ The Norton Anthology of English Literature, 7th edition, vol. 2, p. 1916.

- ^ Herbert N. Schneidau (1991). Waking Giants: The Presence of the Past in Modernism. Oxford University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-19-506862-7. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

the blinded bird.

(Google Books) - ^ "Poetry.org". Poets.org. 11 January 1928. Archived from the original on 14 April 2014. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ "Thomas Hardy", The Norton Anthology of English Literature, 7th edition, vol.2, p. 1916.

- ^ Claire Tomalin. Thomas Hardy, The Time Torn Man (Penguin, 2007), pp. 46–47.

- ^ Wotton, G. (1985), Thomas Hardy: Towards A Materialist Criticism, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, p.36

- ^ Florence Emily Hardy, The Early Life of Thomas Hardy, 1840–1891, p. 269

- ^ a b Ellman, Richard, & O'Clair, Robert (eds.) 1988. "Thomas Hardy" in The Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry, Norton, New York.

- ^ "Pearson Literature: Biography: Thomas Hardy". Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- ^ "Adelene Buckland: Thomas Hardy, Provincial Geology and the Material Imagination". Archived from the original on 1 April 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Trish Ferguson. "Time's Renewal": Death and Immortality in Thomas Hardy's Emma poems, Literature and Modern Time: Technological Modernity, Glimpses of Eternity, Experiments with Time, Palgrave, 2020.

- ^ "Thomas Hardy's Wessex". St-andrews.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 28 February 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ "Thomas Hardy's Wessex: The Evolution of Wessex". St-andrews.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ Gamble, Cynthia, 2015 Wenlock Abbey 1857–1919: A Shropshire Country House and the Milnes Gaskell Family, Ellingham Press.

- ^ Terry R. Wright. "Hardy's Heirs: D. H. Lawrence and John Cowper Powys" in A Companion to Thomas Hardy. Chichester, Sussex: John Wiley, 2012.[1] Archived 11 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Terry R. Wright. "Hardy's Heirs: D. H. Lawrence and John Cowper Powys"

- ^ Morine Krissdottir, Descents of Memory: The Life of John Cowper Powys. (New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2007), p. 312.

- ^ Herbert Williams, John Cowper Powys. (Bridgend, Wales: Seren, 1997), p. 94.

- ^ "Cakes and Ale". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Christopher Durang. The Marriage of Bette and Boo. New York: Grove Press, 1987.[2] Archived 15 September 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Song cycle Earth and Air and Rain (1936)

- ^ "Biography " Gerald Finzi Official Site". Geraldfinzi.com. 27 September 1956. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ Song cycle Winter Words (1953)

- ^ Cantata Hodie (1954)

- ^ "Gustav Holst (Vocal Texts and Translations for Composer Gustav Holst)". LiederNet Archive. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ Three Songs to Poems by Thomas Hardy

- ^ The Past and I: 100 Years of Thomas Hardy, Delphian Records DCD34307 (2024)

- ^ Sampson, Kevin (21 July 2001). "Taking the biscuit". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ See for example the song title "Thy Damnation Slumbereth Not", which is a quotation from Thomas Hardy's novel Tess of the d'Urbervilles,Hardy, Thomas (1891). Tess of the d'Urbervilles. Chapter 12. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2015. which is itself an adaptation of the Second Epistle of Peter at 2:3: "Their damnation slumbereth not".

- ^ Gilmore, Dehn (2014). The Victorian Novel and the Space of Art: Fictional Form on Display. Cambridge University Press. p. 207.

- ^ Purdy, Richard (October 1944). "Thomas Hardy And Florence Henniker: The Writing Of "The Spectre of the Real". Colby Library Quarterly. 1 (8): 122–6. Archived from the original on 24 May 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ Axelrod, Jeremy. "Thomas Hardy". The Poetry Foundation. Archived from the original on 10 July 2010. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ “Thomas Hardy poems” Archived 22 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

Biographies and criticism

[edit]- Armstrong, Tim. "Player Piano: Poetry and Sonic Modernity" in Modernism/Modernity 14.1 (January 2007), 1–19.

- Beatty, Claudius J.P. Thomas Hardy: Conservation Architect. His Work for the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society 1995. ISBN 0-900341-44-0

- Blunden, Edmund. Thomas Hardy. New York: St. Martin's, 1942.

- Brady, Kristen. The Short Stories of Thomas Hardy. London: Macmillan, 1982.

- Boumelha, Penny. Thomas Hardy and Women. New Jersey: Barnes and Noble, 1982.

- Brennecke, Jr., Ernest. The Life of Thomas Hardy. New York: Greenberg, 1925.

- Cecil, Lord David. Hardy the Novelist. London: Constable, 1943.

- D'Agnillo, Renzo, "Music and Metaphor in Under the Greenwood Tree, in The Thomas Hardy Journal, 9, 2 (May 1993), pp.39–50.

- D'Agnillo, Renzo, "Between Belief and Non-Belief: Thomas Hardy’s 'The Shadow on the Stone'”, in Thomas Hardy, Francesco Marroni and Norman Page (eds), Pescara, Edizioni Tracce, 1995, pp. 197–222.

- Deacon, Lois and Terry Coleman. Providence and Mr. Hardy. London: Hutchinson, 1966.

- Draper, Jo. Thomas Hardy: A Life in Pictures. Wimborne, Dorset: The Dovecote Press.

- Ellman, Richard & O'Clair, Robert (eds.) 1988. "Thomas Hardy" in The Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry, Norton, New York.

- Gatrell, Simon. Hardy the Creator: A Textual Biography. Oxford: Clarendon, 1988.

- Gibson, James. Thomas Hardy: A Literary Life. London: Macmillan, 1996.

- Gibson, James. Thomas Hardy: Interviews and Recollections. London: Macmillan, 1999; New York: St Martin's Press, 1999.

- Gittings, Robert. Thomas Hardy's Later Years. Boston : Little, Brown, 1978.

- Gittings, Robert. Young Thomas Hardy. Boston : Little, Brown, 1975.

- Gittings, Robert and Jo Manton. The Second Mrs Hardy. London: Heinemann, 1979.

- Gossin, P. Thomas Hardy's Novel Universe: Astronomy, Cosmology, and Gender in the Post-Darwinian World. Aldershot, Ashgate, 2007 (The Nineteenth Century Series).

- Halliday, F. E. Thomas Hardy: His Life and Work. Bath: Adams & Dart, 1972.

- Hands, Timothy. Thomas Hardy : Distracted Preacher? : Hardy's religious biography and its influence on his novels. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1989.

- Hardy, Evelyn. Thomas Hardy: A Critical Biography. London: Hogarth Press, 1954.

- Hardy, Florence Emily. The Early Life of Thomas Hardy, 1840–1891. London: Macmillan, 1928.

- Hardy, Florence Emily. The Later Years of Thomas Hardy, 1892–1928 London: Macmillan, 1930.

- Harvey, Geoffrey. Thomas Hardy: The Complete Critical Guide to Thomas Hardy. New York: Routledge (Taylor & Francis Group), 2003.

- Hawkins, Desmond. Thomas Hardy. London: Arthur Barker, 1950. (The English Novelists series)

- Hedgcock, F. A., Thomas Hardy: penseur et artiste. Paris: Librairie Hachette, 1911.

- Holland, Clive. Thomas Hardy O.M.: The Man, His Works and the Land of Wessex. London: Herbert Jenkins, 1933.

- Jedrzejewski, Jan. Thomas Hardy and the Church. London: Macmillan, 1996.

- Johnson, Lionel Pigot. The Art of Thomas Hardy (London: E. Mathews, 1894).

- Kay-Robinson, Denys. The First Mrs Thomas Hardy. London: Macmillan, 1979.

- Langbaum, Robert. "Thomas Hardy in Our Time." New York: St. Martin's Press, 1995, London: Macmillan, 1997.

- Marroni, Francesco, "The Negation of Eros in 'Barbara of the House of Grebe' ", in "Thomas Hardy Journal", 10, 1 (February 1994) pp. 33–41

- Marroni, Francesco and Norman Page (eds.), Thomas Hardy. Pescara: Edizioni Tracce, 1995.

- Marroni, Francesco, La poesia di Thomas Hardy. Bari: Adriatica Editrice, 1997.

- Marroni, Francesco, "The Poetry of Ornithology in Keats, Leopardi, and Hardy: A Dialogic Analysis", in "Thomas Hardy Journal", 14, 2 (May 1998) pp. 35–44

- Millgate, Michael (ed.). The Life and Work of Thomas Hardy by Thomas Hardy. London: Macmillan, 1984.

- Millgate, Michael. Thomas Hardy: A Biography. New York: Random House, 1982.

- Millgate, Michael. Thomas Hardy: A Biography Revisited. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Morgan, Rosemarie, (ed) The Ashgate Research Companion to Thomas Hardy, (Ashgate Publishing), 2010.

- Morgan, Rosemarie, (ed) The Hardy Review,(Maney Publishing), 1999–.

- Morgan, Rosemarie, Student Companion to Thomas Hardy (Greenwood Press), 2006.

- Morgan, Rosemarie, Cancelled Words: Rediscovering Thomas Hardy (Routledge, Chapman & Hall),1992

- Morgan, Rosemarie, Women and Sexuality in the Novels of Thomas Hardy (Routledge & Kegan Paul), 1988; paperback: 1990.

- Musselwhite, David, Social Transformations in Hardy's Tragic Novels: Megamachines and Phantasms, Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

- Norman, Andrew. Behind the Mask, History Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0-7524-5630-0

- O'Sullivan, Timothy. Thomas Hardy: An Illustrated Biography. London: Macmillan, 1975.

- Orel, Harold. The Final Years of Thomas Hardy, 1912–1928. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1976.

- Orel, Harold. The Unknown Thomas Hardy. New York: St. Martin's, 1987.

- Page, Norman, ed. Thomas Hardy Annual. No. 1: 1982; No. 2: 1984; No. 3: 1985; No. 4: 1986; No. 5; 1987. London: Macmillan, 1982–1987.

- Phelps, Kenneth. The Wormwood Cup: Thomas Hardy in Cornwall. Padstow: Lodenek Press, 1975.

- Pinion, F. B. Thomas Hardy: His Life and Friends. London: Palgrave, 1992.

- Pite, Ralph. Thomas Hardy: The Guarded Life. London: Picador, 2006.

- Saxelby, F. Outwin. A Thomas Hardy dictionary : the characters and scenes of the novels and poems alphabetically arranged and described (London: G. Routledge, 1911).

- Seymour-Smith, Martin. Hardy. London: Bloomsbury, 1994.

- Stevens-Cox, J. Thomas Hardy: Materials for a Study of his Life, Times, and Works. St. Peter Port, Guernsey: Toucan Press, 1968.

- Stevens-Cox, J. Thomas Hardy: More Materials for a Study of his Life, Times, and Works. St. Peter Port, Guernsey: Toucan Press, 1971.

- Stewart, J. I. M. Thomas Hardy: A Critical Biography. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1971.

- Taylor, Richard H. The Neglected Hardy: Thomas Hardy's Lesser Novels. London: Macmillan; New York: St Martin's Press, 1982.

- Taylor, Richard H., ed. The Personal Notebooks of Thomas Hardy. London: Macmillan, 1979.

- Tomalin, Claire. Thomas Hardy. New York: Penguin Press, 2006.

- Turner, Paul. The Life of Thomas Hardy: A Critical Biography. Oxford: Blackwell, 1998.

- Weber, Carl J. Hardy of Wessex, His Life and Literary Career. New York: Columbia University Press, 1940.

- Wilson, Keith. Thomas Hardy on Stage. London: Macmillan, 1995.

- Wilson, Keith, ed. Thomas Hardy Reappraised: Essays in Honour of Michael Millgate. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006.

- Wilson, Keith, ed. A Companion to Thomas Hardy. Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

- Wotton, George. Thomas Hardy: Towards A Materialist Criticism. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 1985.

External links

[edit]- Digital collections

- Works by Thomas Hardy in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Thomas Hardy at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Thomas Hardy at the Internet Archive

- Works by Thomas Hardy at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Thomas Hardy at the Poetry Foundation

- A Hyper-Concordance to the Works of Thomas Hardy at the Victorian Literary Studies Archive, Nagoya University, Japan

- Physical collections

- Dorset Museum, Dorchester, Dorset, contains the largest Hardy collections in the world, donated directly to the Museum by the Hardy family and inscribed on the UNESCO Memory of the World register for the United Kingdom.

- Thomas Hardy Collection at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin

- Thomas Hardy Archived 27 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine at the British Library

- Letter from Hardy to Bertram Windle, transcribed by Birgit Plietzsch, from Collected Letters, vol. 2, pp. 131–133 Archived 26 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- Biographical information

- Geographic information

- Hardy's Cottage National Trust visitor information for Hardy's birthplace.

- Hardy Country A visitor guide for 'Hardy Country' in Dorset (sites of interest).

- Max Gate National Trust visitor information for Max Gate (the home Hardy designed, lived and died in).

- Other links

- The Thomas Hardy Association (TTHA)

- The Thomas Hardy Society

- The New Hardy Players Theatrical group specialising in the works of Thomas Hardy.

- Newspaper clippings about Thomas Hardy in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- The Dynasts on Great War Theatre

- Thomas Hardy

- 1840 births

- 1928 deaths

- 19th-century English short story writers

- 19th-century English novelists

- 19th-century English poets

- 20th-century English male writers

- Alumni of King's College London

- English anti-vivisectionists

- English male poets

- Burials at Westminster Abbey

- English male novelists

- English male short story writers

- English short story writers

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature

- Members of the Order of Merit

- Pantheists

- People from Dorchester, Dorset

- Victorian novelists

- Victorian poets

- Presidents of the Society of Authors

- Victorian short story writers

- English satirical poets