Hadrosauridae

| Hadrosaurids Temporal range: Late Cretaceous

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Parasaurolophus cyrtocristatus at Field Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Superorder: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Infraorder: | |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | Hadrosauridae Cope, 1869

|

| Subfamilies | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

Hadrosaurids or duck-billed dinosaurs are members of the family Hadrosauridae, and include ornithopods such as Edmontosaurus and Parasaurolophus. They were common herbivores in the Upper Cretaceous Period of what are now Asia, Europe and North America. They are descendants of the Upper Jurassic/Lower Cretaceous iguanodontian dinosaurs and had similar body layout. They were ornithischians.

Hadrosaurids are divided into two subfamilies. The lambeosaurines (Lambeosaurinae) have large cranial crests or tubes, and are less bulky. The hadrosaurines (Hadrosaurinae) lack the cranial crests or tubes and are larger.

Characteristics

The hadrosaurs are known as the duck-billed dinosaurs due to the similarity of their head to that of modern ducks. In some genera, most notably Anatotitan, the whole front of the skull was flat and broadened out to form a beak, ideal for clipping leaves and twigs from the forests of Asia, Europe and North America. However, the back of the mouth contained literally thousands of teeth suitable for grinding food before it was swallowed. This has been hypothesized to have been a crucial factor in the success of this group in the Cretaceous, compared to the sauropods which were still largely dependent on gastroliths for grinding their food.

Discoveries

Hadrosaurids were the first dinosaur family to be identified in North America, the first traces being found in 1855-1856 with the discovery of fossil teeth. Joseph Leidy examined the teeth, and erected the genera Trachodon and Thespesius (others included Troodon, Deinodon and Palaeoscincus). One species was named Trachodon mirabilis. Now it seems that the teeth genus Trachodon is a mixture of all sorts of cerapod dinosaurs, including ceratopsids. In 1858 the teeth were associated with Leidy's eponymous Hadrosaurus foulkii, named after the fossil hobbyist William Parker Foulke. More and more teeth were found, resulting in even more (now obsolete) genera.

A second duck-bill skeleton was unearthed, and was named Diclonius mirabilis in 1883 by Edward Drinker Cope, which he incorrectly used in favor of Trachodon mirabilis. But Trachodon, together with other poorly typed genera, was used more widely and, when Cope's famous "Diclonius mirabilis" skeleton was mounted at the American Museum of Natural History, it was labeled as "Trachodont dinosaur". The duck-billed dinosaur family was then named Trachodontidae.

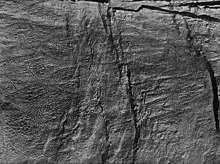

A very well-preserved complete hadrosaurid specimen (Edmontosaurus annectens) was recovered in 1908 by the fossil collector Charles Hazelius Sternberg and his three sons, in Converse County, Wyoming. Analyzed by Henry Osborn in 1912, it has come to be known as the "Trachodon mummy". This specimen's skin was almost completely preserved in the form of impressions.

Lawrence Lambe erected the genus Edmontosaurus ("lizard from Edmonton") in 1917 from a find in the lower Edmonton Formation (now Horseshoe Canyon Formation), Alberta. Hadrosaurid systematics were a mess until 1942, when Richard Swann Lull and Nelda Wright proposed the genus Anatosaurus. Cope's famous mount at the AMNH became Anatosaurus copei. In 1975, Anatosaurus was moved to Edmontosaurus, because the species were just too similar to the Edmontosaurus type species, E. regalis and because Edmontosaurus was older, it had precedence. The original sample was probably a young Edmontosaurus. One former Anatosaurus species was distinct enough from Edmontosaurus to be placed in a separate genus, named Anatotitan, so in 1990 the AMNH mount was re-labelled Anatotitan copei.

Paleontologists have found a hadrosaurid leg bone in Paleocene rocks, but it was probably reworked from a Cretaceous source.[1]

One of the most complete fossilized specimens was found in 1999 in Hell Creek Formation of North Dakota and now is nicknamed "Dakota". The hadrosaur fossil is so well preserved that scientists have been able to calculate its muscle mass and learn that it was more muscular than thought, probably giving it the ability to outrun predators such as Tyrannosaurus rex. Unlike the collections of bones found in museums, this mummified hadrosaur fossil comes complete with skin (not merely skin impressions), ligaments, tendons and possibly some internal organs. It is being analyzed in the world's largest CT scanner, operated by the Boeing Co.[2] The machine usually is used for detecting flaws in space shuttle engines and other large objects, but previously none as large as this. Researchers hope the technology will help them learn more about the fossilized insides of the creature. They also found a gap of about a centimeter between each vertebra, indicating there may have been a disk or other material between them, allowing more flexibility and meaning the animal was actually longer than what is shown in a museum.[3]

Systematics

Taxonomy

The family Hadrosauridae was first used by Edward Drinker Cope in 1869. Since its creation, a major division has been recognized in the group, between the (generally crested) subfamily Lambeosaurinae and (generally crestless) subfamily Hadrosaurinae. Phylogenetic analysis has increased the resolution of hadrosaurid relationships considerably (see Phylogeny below), leading to the widespread usage of tribes (a taxonomic unit below subfamily) to describe the finer relationships within each group of hadrosaurids. However, many hadrosaurid tribes commonly recognized in online sources have not yet been formally defined or seen wide use in the literature. Several were briefly mentioned but not named as such in the first edition of The Dinosauria, under informal names. In this 1990 reference, "gryposaurs" included Aralosaurus, Gryposaurus, Hadrosaurus, and Kritosaurus; "brachylophosaurs" included Brachylophosaurus and Maiasaura; "saurolophs" included Lophorhothon, Prosaurolophus, and Saurolophus; and "edmontosaurs" included Anatotitan, Edmontosaurus, and Shantungosaurus.[4]

Lambeosaurines have also been split into Parasaurolophini (Parasaurolophus) and Corythosaurini (Corythosaurus, Hypacrosaurus, and Lambeosaurus).[5] Corythosaurini and Parasaurolophini as terms entered the formal literature in Evans and Reisz's 2007 redescription of Lambeosaurus magnicristatus. Corythosaurini is defined as all taxa more closely related Corythosaurus casuarius than to Parasaurolophus walkeri, and Parasaurolophini as all those taxa closer to P. walkeri than to C. casuarius. In this study, Charonosaurus and Parasaurolophus are parasaurolophins, and Corythosaurus, Hypacrosaurus, Lambeosaurus, Nipponosaurus, and Olorotitan are corythosaurins.[6]

The following taxonomy includes dinosaurs currently referred to the Hadrosauridae and its subfamilies. Hadrosaurids that were accepted as valid but were not placed in a cladogram at the time of the 2004 review in The Dinosauria,[7] or, in the case of lambeosaurines, the 2007 redescription of Lambeosaurus magnicristatus,[6] are included at the highest level to which they were placed (either then, or in their description if they postdate the papers used here).

- Family Hadrosauridae

- Telmatosaurus

- Subfamily Hadrosaurinae

- Brachylophosaurus

- Edmontosaurus (including Anatotitan in Horner et al., 2004[7])

- Gryposaurus

- "Kritosaurus" australis

- Lophorhothon

- Maiasaura

- Naashoibitosaurus

- Prosaurolophus

- Saurolophus

- Wulagasaurus [8]

- Hadrosaurinae incertae sedis

- Subfamily Lambeosaurinae

- Hadrosaurids of uncertain placement (incertae sedis)

- Dubious hadrosaurids

Phylogeny

Hadrosauridae was first defined as a clade, by Forster in a 1997 abstract, as simply "Labeosaurinae plus Hadrosaurinae and their most recent common ancestor." In 1998, Paul Sereno defined the clade Hadrosauridae as the most inclusive possible group containing Saurolophus (a well-known hadrosaurine) and Parasaurolophus (a well-known lambeosaurine), later emending the definition to include Hadrosaurus, the type genus of the family, which ICZN rules state must be included, despite its status as a nomen dubium. According to some studies,[who?] Sereno's definition would place a few other well-known hadrosaurs (such as Telmatosaurus and Bactrosaurus) outside the family, which led Horner et al. (2004) to define the family to include Telmatosaurus by default.

The following cladogram is after the 2004 review by Jack Horner, David B. Weishampel, and Catherine Forster, in the second edition of The Dinosauria.[7]

| Hadrosauridae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hadrosaurinae per Gates and Sampson (2007)

Hadrosauridae has not been subjected to as many phylogenetic analyses as other dinosaur groups, so other workers may find quite different phylogenies. Gates and Sampson (2007) published the following alternate cladogram of Hadrosaurinae in their description of Gryposaurus monumentensis:[10]

| <font color="white">unnamed |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lambeosaurinae cladogram

The following cladogram is after the 2007 redescription of Lambeosaurus magnicristatus (Evans and Reisz, 2007):[6]

| Hadrosauridae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lifestyle

Diet

Coprolites (fossilized droppings) of some Late Cretaceous hadrosaurs show that the animals sometimes deliberately ate rotting wood. Wood itself is not nutritious, but decomposing wood would have contained fungi, decomposed wood material and detritus-eating invertebrates, all of which would have been nutritious.[11]

Cultural depictions of hadrosaurids

In the Star Trek: Voyager episode "Distant Origin," the crew meets a bipedal space faring matriarchal civilization called the Voth, descended from hadrosaurs who had left earth before the extinction of other dinosaurs.

References

- ^ Fassett, J, Zielinski, R.A., and Budahn, J.R. (2002). Dinosaurs that did not die; evidence for Paleocene dinosaurs in the Ojo Alamo Sandstone, San Juan Basin, New Mexico. In: Koeberl, C., and MacLeod, K. (eds.). Catastrophic events and mass extinctions: impacts and beyond. Special Paper - Geological Society of America 356:307-336.

- ^ (Reuters News) "Mummified dinosaur reveals surprises: scientists" 3 December 2007.

- ^ SCHMID, RANDOLPH (December 3, 5:52 PM EST). "'Mummified Dinosaur May Have Outrun T Rex". Associated Press. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Weishampel, David B. (1990). "Hadrosauridae". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.) (ed.). The Dinosauria (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 534–561. ISBN 0-520-06727-4.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Glut, Donald F. (1997). Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. p. 69. ISBN 0-89950-917-7.

- ^ a b c Evans, David C. (2007). "Anatomy and relationships of Lambeosaurus magnicristatus, a crested hadrosaurid dinosaur (Ornithischia) from the Dinosaur Park Formation, Alberta". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (2): 373–393. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[373:AAROLM]2.0.CO;2.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Horner, John R. (2004). "Hadrosauridae". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.) (ed.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 438–463. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ a b Godefroit, P., Hai, S., Yu, T., and Lauters, P. (2008). "New hadrosaurid dinosaurs from the uppermost Cretaceous of north−eastern China". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 53 (1): 47–74.

- ^ Gates, Terry A. (2007). "Velafrons coahuilensis, a new lambeosaurine hadrosaurid (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the Late Campanian Cerro del Pueblo Formation, Coahuila, Mexico". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (4): 917–930. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[917:VCANLH]2.0.CO;2.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Gates, Terry A. (2007). "A new species of Gryposaurus (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) from the late Campanian Kaiparowits Formation, southern Utah, USA". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 151 (2): 351–376. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00349.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Chin, K. (2007). "The Paleobiological Implications of Herbivorous Dinosaur Coprolites from the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation of Montana: Why Eat Wood?". Palaios. 22 (5): 554. doi:10.2110/palo.2006.p06-087r. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)