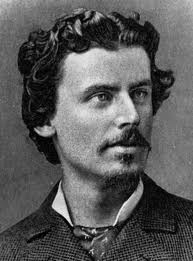

Jean-Marie Guyau

Jean-Marie Guyau | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 28 October 1854 |

| Died | 31 March 1888 (aged 33) |

| Nationality | French |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

Jean-Marie Guyau (28 October 1854 – 31 March 1888) was a French philosopher and poet.

Guyau was inspired by the philosophies of Epicurus, Epictetus, Plato, Immanuel Kant, Herbert Spencer, and Alfred Fouillée, and the poetry and literature of Pierre Corneille, Victor Hugo, and Alfred de Musset.

Life

[edit]Guyau was first exposed to Plato and Kant, as well as the history of religions and philosophy in his youth through his stepfather, the noted French philosopher Alfred Fouillée. With this background, he was able to attain his Bachelor of Arts at only 17 years of age, and at this time, translated the Handbook of Epictetus. At 19, he published his 1300-page "Mémoire" that, a year later in 1874, won a prize from the French Academy of Moral and Political Sciences and helped to earn him a philosophy lectureship at the Lycée Condorcet. However, this was short-lived, as he soon began to suffer from pulmonary disease. Following the first attacks of his disease, he went to southern France where he wrote philosophical works and poetry. He remained there until his death of s pulmonary disease at 33 years of age.[1]

His mother, Augustine Tuillerie (who married Fouillée after Guyau's birth), published Le Tour de France par deux enfants in 1877 under the pseudonym G. Bruno.

Guyau's wife published short novels for young people under the pseudonym of Pierre Ulric.

Philosophy

[edit]Guyau's works primarily analyze and respond to modern philosophy, especially moral philosophy. Largely seen as an Epicurean, he viewed English utilitarianism as a modern version of Epicureanism. Although an enthusiastic admirer of the works of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, he did not spare them a careful scrutiny of their approach to morality.

In his Esquisse d'une morale sans obligation ni sanction, probably his most important work on moral theory, he begins from Fouillée, maintaining that utilitarian and positivist schools, despite admitting the presence of an unknowable in moral theory, wrongly expel individual hypotheses directed towards this unknowable. He states that any valid theory of ethics must consider the moral sphere as consisting not merely of moral facts (the utilitarian approach) but also, and more importantly, of moral ideas. On the other hand, in contrast to Fouillée, he does not see this unknowable itself as able to contribute a "principle practically limiting and restricting conduct," i.e. of "mere justice" which, he states, comes too close to Kantian notions of duty; for this, in turn, would bring us back to a theory of moral obligation, which, as the title suggests, he wishes to free moral theory from. Much of his treatise is dedicated to arguing what moral theory can be based upon that relieves moral theorists from relying on e.g. duty, sanctions, and obligations. For example,

The only admissible "equivalents" or "substitutes" of duty, to use the same language as the author of "La Liberté et le Déterminisme" appear to us to be:

- The consciousness of our inward and superior power, to which we see duty practically reduced.

- The influence exercised by ideas over actions.

- The increasing fusion of the sensibilities, and the increasingly social character of our pleasures and sorrows.

- The love of risk in action, of which we will show the importance hitherto ignored.

- The love of metaphysical hypothesis, which is a sort of risk of thought.[2]

Guyau also took interest in aesthetic theory, particularly its role in society and social evolution. Primarily, Guyau's theories of aesthetics refute Immanuel Kant's idea that aesthetic judgment is disinterested, and accordingly, partitioned off from the faculties of mind responsible for moral judgement. In Les Problèmes de l'esthétique contemporaine, Guyau argues that beauty in fact activates all dimensions of the mind—the sensual, the intellectual, and the moral. Aesthetic sensations are fully integrated with life and morality. They are also the mark of man's self-actualization. Contrary to Herbert Spencer's theory that the development of the arts is an indicator of the decline of society at large, Guyau maintains that as society continues to evolve, life will become increasingly aesthetic. In L'Art au point de vue sociologique, Guyau argues the purpose of art is not to merely produce pleasure, but to create sympathy among members of a society. By extension, he contends that art has the power to reform societies as well as to form them anew.

Guyau authored La genèse de l’idée de temps (English translation The Origin of the Idea of Time), a book on the philosophy of time in 1890.[3] Guyau argued that time itself does not exist in the universe but is produced by events that occur, thus time to Guyau was a mental construction from events that take place. He asserted that time is a product of human imagination, memory and will.[4]

Influence

[edit]Although Guyau is now a relatively obscure philosopher, his approach to philosophy earned him much praise from those who knew of him and his philosophy. Because he rarely made his political ideology explicit, Guyau has been portrayed as a socialist, an anarchist, and as a libertarian liberal in the style of John Stuart Mill. However, Guyau clearly expressed republican sympathies in which he praised the French Revolution, saluted the Third Republic's promotion of civic and moral education, described voting as a "duty," and cautiously argued that democracy offered propitious conditions for creative development.[5]

He is the original source of the notion of anomie, which found much use in the philosophy of Guyau's contemporary Émile Durkheim, who first used it in his review of "Irréligion de l'avenir".[6] He is admired and well-quoted by the anarchist Peter Kropotkin, in Kropotkin's works on ethics, where Guyau is described as an anarchist.[7] Peter Kropotkin devotes an entire chapter to Guyau in his Ethics: Origin and Development, describing Guyau's moral teaching as "so carefully conceived, and expounded in so perfect a form, that it is a simple matter to convey its essence in a few words",[8] while the American philosopher Josiah Royce considered him "one of the most prominent of recent French philosophical critics."[9]

Bibliography

[edit]- Essai sur la morale littéraire. 1873.

- Mémoire sur la morale utilitaire depuis Epicure jusqu'à l'école anglaise. 1873

- Première année de lecture courante. 1875.

- Morale d'Epicure. 1878.

- Morale anglaise contemporaine. 1879.

- Vers d'un philosophe.

- Problèmes de l'esthétique contemporaine. 1884.

- Esquisse d'une morale sans obligation ni sanction. 1884.

- Irréligion de l'avenir. 1886, engl. The Non-religion of the future, New York 1962

- La genèse de l'idée de temps, 1890.

- L'Art au point de vue sociologique. 1889.

- Education et Heredite. Étude sociologique. Paris 1902.

References

[edit]- ^ https://academic.oup.com/edited-volume/57921/chapter/475498334>

- ^ Esquisse d'une morale sans obligation ni sanction, p. 4

- ^ Michon J.A. (1992) Introduction Representing Time. In: Macar F., Pouthas V., Friedman W.J. (eds) Time, Action and Cognition. NATO ASI Series (Series D: Behavioural and Social Sciences), vol 66. Springer, Dordrecht. ISBN 978-90-481-4166-1

- ^ Grondin, Simon. (2008). Psychology of Time. Emerald Group Publishing. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-08046-977-5

- ^ Behrent, Michael C. (2008). "The Mystical Body of Society: Religion and Association in Nineteenth-Century French Political Thought". Journal of the History of Ideas. 69 (2): 235–236. doi:10.1353/jhi.2008.0019. PMID 19127833. S2CID 30590355.

- ^ Orru, p. 499

- ^ Peter Kropotkin (1898). "Anarchist Morality". RevoltLib.

When the Australian, quoted by Guyau, wasted away beneath the idea that he has not yet revenged his kinsman's death; when he grows thin and pale, a prey to the consciousness of his cowardice, and does not return to life till he has done the deed of vengeance, he performs this action, a heroic one sometimes, to free himself of a feeling which possesses him, to regain that inward peace which is the highest of pleasures.

- ^ Ethics: Origin and Development, p. 322

- ^ Orru, p. 501

Further reading

[edit]- Ansell-Pearson, K. (2014). "Morality and the philosophy of life in Guyau and Bergson." Continental Philosophy Review 47(1): 59–85.*

- Michael C. Behrent, "Le débat Guyau-Durkheim sur la théorie sociologique de la religion," Archives de sciences sociales des religions 142 (avr.-juin 2008): 9–26.

- Hoeges, Dirk. Literatur und Evolution. Studien zur französischen Literaturkritik im 19. Jahrhundert. Taine – Brunetière – Hennequin – Guyau, Carl Winter Universitätsverlag, Heidelberg 1980. ISBN 3-533-02857-7

- Jordi Riba, La morale anomique de Jean-Marie Guyau, Paris [etc.] : L'Harmattan, 1999

- Marco Orru, The Ethics of Anomie: Jean Marie Guyau and Emile Durkheim, British Journal of Sociology, Vol. 34, No. 4 (Dec., 1983), pp. 499–518

- 1854 births

- 1888 deaths

- 19th-century French essayists

- 19th-century French male writers

- 19th-century French non-fiction writers

- 19th-century French philosophers

- 19th-century French poets

- 19th-century French translators

- 19th-century French memoirists

- French essayists

- French ethicists

- French male non-fiction writers

- French male poets

- French lecturers

- People from Laval, Mayenne

- French philosophers of art

- Philosophers of mind

- Philosophers of time

- French philosophy academics

- Philosophy writers