Guilsborough

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2009) |

| Guilsborough | |

|---|---|

Village sign, showing witches on a sow | |

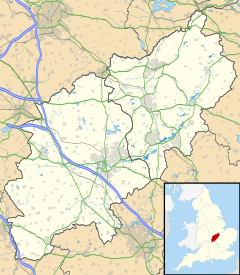

Location within Northamptonshire | |

| Population | 692 (2011) |

| OS grid reference | SP6773 |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Northampton |

| Postcode district | NN6 |

| Dialling code | 01604 |

| Police | Northamptonshire |

| Fire | Northamptonshire |

| Ambulance | East Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

Guilsborough is a village and civil parish in West Northamptonshire in England. At the time of the 2001 census, the parish's population was 882 people,[1] reducing to 692 at the 2011 Census.[2]

It is at the centre of an area of rural villages between the towns of Northampton, Daventry, Rugby and Market Harborough. There is a secondary school, primary school, fire station, pub, a new village shop including a Post Office (formerly the doctor's surgery) and a new doctor's surgery with pharmacy and a Hairdressers.

History

The villages name means 'Gyldi's fortification'. The hundred is named after Guilsborough, but the site of the meeting-place is unknown.[3]

Guilsborough is made up of two hamlets, now joined. Guilsborough (Guildesburgh) and Nortoft. The former referring to the Roman fort, or referencing the earlier Late Bronze Age/Iron Age Enclosure on the same site. Possibility of the name deriving from a later Anglo-Saxon base word 'gebeorgan' (enclosure to save/protect/preserve) given there was an Anglo Saxon settlement over the Late Bronze Age/Iron Age followed by Roman, and the Anglo-Saxon fortified enclosures. The Church Mount road housing stands where Guilsborough Hall once stood. The mound under the water tower in the grounds of the historic Guilsborough Park is part of a Late Bronze Age or Early Iron Age enclosure (RCHME 1981) being fifth century BC to first century BC with later Roman occupation. Subsequent excavation cites evidence of there being a strongly defended univallate fort of late first Millennium BC. Other remains of the enclosure (northern ramparts) still exist in paddocks to the north-east and east of the mound Potential Iron Age iron production site. Whilst most of the southern rampart was destroyed in 1947 and possibly during an earlier episode, some remnants may exist. The Roman fort was an outpost of the settlement at West Haddon and the Guilsborough encampment is believed to have been the work of Publius Ostorius Scapula, under the reign of Claudius. When the south rampart was removed in the 19th century, many skeletons were found.[4] The whole site is a Scheduled Ancient Monument (in process - Northamptonshire Sites and Monument Records). The Guilsborough Park landscape related to the former Guilsborough Hall. Various significant trees and tree groups remain (with TPO's) and other important landscape features include the brick water tower of the hall and the hall gates.

In the fields east of Guilsborough and both north and south of the West Haddon Road (just east of the 'PCS' access road) lie recorded prehistoric and Iron Age remains. A Saxon settlement also seems likely to have been located along the brook by the gated road (east west across Cold Ashby Road and obvious landforms can be seen immediately west of the old mill and stables.).

In the two fields below Nortoft (Danish/Norse: Toft is a place and/or house or farm or clearing; Nor- may mean to the north (of what?)) at the spring line below the Ironstone, on both sides of the road, lie the remains of a Saxon fishponds complex with associated village lying at the top of the fish ponds. The outlines of ponds are visible, along with house platforms and the remnants of a track (East West) are still visible. They would have been fed by water from the spring line. Spring based water course still flow on both sides of Nortoft. The ponds in the private gardens of Manor House, and the existing fish pond (since enlarged) may have had their origins as Saxon ponds. Local knowledge suggest that the village burnt down, but as yet there is not collaborative evidence. Nortoft Cottage, which has a very old cob cottage at its heart is thought to be the only remaining building of the original Nortoft, so might have its origins as part of the Saxon settlement.

A cell of Premonstratensian canons was founded at Kalendar or Kayland (on the border of Guilsborough and Cottesbrooke Parishes near Nortoft), probably soon after Sulby Abbey (c1155), and as it does not appear in the taxation of 1291, had probably ceased by then. The Kayland meadow held a cell of Premonstratension canons. Large foundation stones have been dug up and the cell appears to have been moated (English Heritage Pastscapes 341939) and possible fishponds.

Folklore

The Guilsborough Witches

On 22 July 1612, four women and one man were hanged at Abington Gallows in Northampton for the crime of witchcraft, also known as the Northamptonshire Witch Trials. Of those five, Agnes Brown and her daughter Ioane/Joan Vaughan (or Varnham) were from Guilsborough. They stood accused of bewitching a local noblewoman, Elizabeth Belcher (née Fisher) and her brother-in-law Master Avery and of killing, by sorcery, a child and numerous livestock.[5][6][7]

Although the hangings can be legitimately traced back to actual historic events, the story most commonly repeated is of less certain origins. The tale goes that there was an elderly witch called Mother Roades, who lived just outside the neighbouring village of Ravensthorpe. Before she could be arrested and tried for her crimes of sorcery, she died. Her final words told of her friends riding to see her, but that it did not matter because they would meet again in some other place before the month was out.

Her friends were thus apprehended riding on the back of a sow between Guilsborough and Ravensthorpe and were taken into custody and hanged, thus they were all reunited in death. The problem with this story is that, although Agnes Brown remains a constant upon the pig's back, her companions swap names depending on the version being read. Three witches were on the pig, but the potential riders, other than Agnes Brown (who appears as one of the riders in all versions), are: Kathryn Gardiner, Alice Abbott, Alice Harrys and Ioan/Joan Lucas. It would appear from records that all of these accused stood trial together, however the reporting only covers the hangings of one day in 1612, so the fates of the others are not known.[8]

Pell's Pool

Guilsborough used to have its own version of Black Annis who lived in Pell's Pool. This was a deep pool which stood off Cold Ashby Lane and was used by the local fire service as a water supply for many years. The pool has now dried up and a house stands there. Young boys and girls were told not to go walking by the pool at night otherwise a witch would drag them down into the water.

Landmarks

Saint Etheldreda's Church

A church at Guilsborough is mentioned in the Domesday Book (1086), but there is no evidence of an Anglo-Saxon church remaining. Guilsborough was probably 'Christianised' by the monks of Brixworth, an outpost of the monastery of Peterborough or, as it was then called, Medeshamsted. The church was possibly a minster of Brixworth, which is one of the oldest remaining Saxon churches in England. There are Anglo-Saxon remnants among the Norman architecture of Guilsborough church.

The oldest part of the current church is the tower which was built during the first half of the 13th century. The nave was completed around 1400 and the north and south porches added during the 18th century. The tower arch was closed about 1700 when a large gallery was erected in front of it to accommodate the boys from the grammar school. An extensive restoration was carried out between the years 1815 and 1820, including the oak roof, preserving the bosses carved in wood illustrating the Seven Ages of Man. The vicar gave the open seats of oak in the nave. Another extensive restoration of the Church took place in 1923 and 1924 when the Chancel was distempered, the roof repaired and the pillars and arches of the nave cleaned of plaster to show off the stone-work. The gallery at the west end was removed and a sub-arch under the chancel arch was taken down. Fairly recently, a number of projects have taken place: conversion of the north porch into a toilet and kitchen; provision of a sound, audio and loop system; and, in celebration of the Queen's Golden Jubilee, external floodlighting. Recently,[when?] the south porch entrance and footpath have been improved giving better access for disabled visitors.

There are rumours that it may have been founded by Saint Wilfred; however these probably belong to the realm of myth and legend. This church was originally dedicated to St Wilfred and it is unusual to see a renaming in favour of a female saint. However, Wilfred and Etheldreda's paths are said to have crossed when Wilfred supported the Anglian queen's decision not to grant her second husband conjugal rights. Despite having been married once before, it is said that St Etheldreda (also known as St Audrey, from where the word 'tawdry' originates) remained a virgin.[9]

Another unusual aspect to this saint is that she appears to have two saint's days. The most commonly cited day is 21 June, however, certainly around the 17th century, villagers in Guilsborough were celebrating her feast day on the first Sunday after 17 October.[10]

The Renton family

Ethel Renton and her daughter, Eleanor Friedberger (née Renton), were prolific local historians writing in the 1920s. To commemorate the millennium, their work was republished as: The Records of Guilsborough, Nortoft and Hollowell. This was originally published in 1929 by T. Beaty Hart Ltd, Bridewell Printing Works, Kettering. The Rentons were also heavily involved in the local Women's Institute and were responsible for the tapestry of the witches in the village hall. The Rentons lived at Guilsborough House.[11]

Schools

Guilsborough has a secondary school and primary school. The secondary school, Guilsborough Academy, is on the edge of the village and takes children from 11 to 18, including a sixth form. Guilsborough School is in the top 500 schools for GCSE and A levels. It takes children from surrounding villages and has about 1,500 pupils. The school had a total of 1311 pupils on roll during 2016–2017 of which 49.3% were girls and 50.7% were boys.[12] The school currently has technology college status.

See also

References

- ^ Office for National Statistics: Guilsborough CP: Parish headcounts. Retrieved 10 November 2009

- ^ "Civil Parish population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ^ "Key to English Place-names".

- ^ Ethel Renton, Eleanor Friedberger, The Records of Guilsborough, Nortoft and Hollowell, 1929, by T. Beaty Hart Ltd, Bridewell Printing Works, Kettering.

- ^ A Brief History of Witchcraft Relating to The Witches of Northamptonshire Reprinted by Taylor & Son 1867. Facsimile by General Coe Ltd, Wilbarston, Northants; April 1967

- ^ Witchcraft and Demonianism by C. L'Estrange Ewen 1970

- ^ Witchcraft in England 1558-1618 edited by Barbara Rosen 1991.

- ^ Witchcraft and Demonianism by C. L'Estrange Ewen 1970, pps. 211-1

- ^ The Oxford Book of Saints

- ^ Dissertation by T. R. Slater 1982, Northamptonshire Records Office

- ^ "Engagement announcement: Ivor Mathews Hedley, youngest son of Dr. & Mrs. Hedley, Cleveland Lodge, Middlesbrough, and Sylvia Ethel Renton, daughter of the late W. Gordon Renton, of Guilsborough House, Northampton & the late Mrs. Renton". The Times. 4 December 1923. p. 15. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ "Guilsborough Academy - GOV.UK".

External links

![]() Media related to Guilsborough at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Guilsborough at Wikimedia Commons