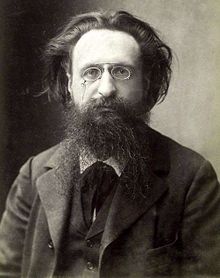

Jules Guesde

Jules Guesde | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Jules Bazile 11 November 1845 |

| Died | 28 July 1922 (aged 76) |

| Political party | French Workers' Party Socialist Party of France SFIO |

| Parent(s) | François Bazile Eléonore Guesde |

| Relatives | Lilian Constantini[1] (granddaughter) Dominique Schneidre[1] (great-granddaughter) |

Jules Bazile, known as Jules Guesde (French: [ʒyl ɡɛːd]; 11 November 1845 – 28 July 1922) was a French socialist journalist and politician.

Guesde was the inspiration for a famous quotation by Karl Marx. Shortly before Marx died in 1883, he wrote a letter to Guesde and Paul Lafargue, both of whom already claimed to represent "Marxist" principles. Marx accused them of "revolutionary phrase-mongering".[2] This exchange is the source of Marx's remark, reported by Friedrich Engels: "ce qu'il y a de certain c'est que moi, je ne suis pas marxiste" ("what is certain is that [if they are Marxists], [then] I myself am not a Marxist").

Biography

[edit]Early years

[edit]Jules Bazile was born in Paris, on the Île-St-Louis. He began his career as a clerk in the Interior Ministry. He wrote in republican newspapers under the Second Empire and chose "Jules Guesde" as a pen name after his mother's name, Eléonore Guesde. On the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War, he was editing Les Droits de l'Homme at Montpellier, and had to take refuge in Geneva in 1871 from a prosecution instituted on account of articles which had appeared in his paper in defence of the Paris Commune.[3] There he read the works of Karl Marx.

In 1876, he returned to France to become one of the chief French advocates of Marxism, being imprisoned for six months in 1878 for taking part in the first Parisian International Congress. He edited at different times Les Droits de l’Homme, Le Cri du peuple, and Le Socialiste, but his best-known organ was the weekly Égalité.[4]

Guesde, who was in prison at the time, was the author of a resolution moved by the delegates from Paris at the Socialist Workers' Congress (1879) and carried by a large majority.[5] It was:

Property is the one social question. Seeing that the present system of property is opposed to those equal rights that will condition the society of the future; that it is unjust and inhuman that some should produce everything and others nothing, and that it is precisely the latter who have all the wealth, all the enjoyment, and all the privilege; seeing that this state of affairs will not be put an end to by the good-will of those whose whole interest lies in its continuance; the Congress adopts as its end and aim the collective ownership of the soil, the subsoil, the instruments of labour, raw materials, and would render them for ever inalienable from that society to which they ought to return.[5]

Guesde had been in close association with Paul Lafargue, and through him with Karl Marx, whose daughter Lafargue had married. It was in conjunction with Marx and Lafargue that he drew up the programme accepted by the National Congress of the French Workers' Party at Le Havre in 1880, which laid stress on the formation of an international labour party working by revolutionary methods. The following year, at the Reims Congress, the orthodox Marxist programme of Guesde was opposed by the "possibilists", who rejected the intransigent attitude of Guesde for the reformist policy of Paul Brousse and Benoît Malon.[6]

Leader of the intransigents

[edit]

At the Congress of Saint-Étienne, the difference developed into division. Those who refused all compromise with a capitalist government followed Guesde, while the reformists formed several groups. Guesde took his full share in the consequent discussions between the Guesdists, the Blanquists, the Possibilists, and others. In 1893 he was returned to the Chamber of Deputies for Roubaix,[7] with a large majority over the Christian Socialist and Radical candidates. He brought forward various proposals in social legislation forming the programme of the Workers' Party, without reference to the divisions among the Socialists, and, on 20 November 1894, succeeded in raising a two days' discussion of the collectivist principle in the Chamber.[6]

In 1902 he was not re-elected, but resumed his seat in 1906. In 1903 there was a formal reconciliation at the Reims Congress of the sections of the party, which then took the name of the Socialist Party of France.[6] All socialist tendencies were then unified in 1905 in the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO), the French section of the Second International. Guesde, nevertheless, continued to oppose the reformist policy of Jean Jaurès, whom he denounced for supporting one "bourgeois" party against another. In 1900, he had already opposed him on the question of socialist participation in "bourgeois" government.[8] His defence of the principle of freedom of association led him, incongruously enough, to support the religious Congregations against Émile Combes's Separation of the Churches and the State.

During the revolt of the Languedoc winegrowers on 11 June 1907, Jaurès, who defended the vine growers cause in the Chamber of Deputies, filed a counter-bill with Jules Guesde. The two socialist deputies proposed nationalization of the wine estates.[9]

Later life

[edit]The outbreak of World War I, which was regarded as threatening France's existence, had the effect of changing the uncompromising attitude of Guesde. In August 1914, while the Reformist Jaurès was assassinated due to his opposition to the war, Guesde was included in the national unity government of René Viviani as a Minister without Portfolio in 1914, and continued to serve as Minister of State from 1915 until the end of 1916.[10] During this period, he adopted patriotic positions and sometimes even nationalist views. Guesde thought that the war would give birth to a social revolution in France and would thus be the starting point of an international revolution.[11]

After the armistice, in the Congress of Tours, he chose the "old house" SFIO following Léon Blum and Jean Longuet, against the majority which created the French Section of the Communist International, the future Communist Party, for which he was condemned by Vladimir Lenin.[11]

Death and legacy

[edit]Guesde died on 28 July 1922.

Besides his numerous political and socialist pamphlets, in 1901, he published two volumes of his speeches in the Chamber of Deputies entitled Quatre ans de lutte de classe 1893-1898 (Four years of class struggle).[6]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b Tami Williams, Germaine Dulac: A Cinema of Sensations, Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2014, p. 164 [1]

- ^ "Programme of the French Worker's Party". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2023-04-27.

- ^ Chisholm 1911, p. 672.

- ^ Chisholm 1911, pp. 672–673.

- ^ a b Lafargue 1897, pp. 445–458.

- ^ a b c d Chisholm 1911, p. 673.

- ^ Stone, Judith F. (August 1, 1985). The Search for Social Peace: Reform Legislation in France, 1890-1914. SUNY series in modern European social history. Albany (New York), USA: State University of New York Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-887-06023-6. Retrieved 2015-10-10.

In 1893, fifty socialists were elected to the Chamber. Among them were Jules Guesde for Roubaix, and the leading independents, Alexandre Millerand for the Parisian twelfth arrondissement and Jean Jaurès for Carmaux in the Midi.

- ^ (in French) See the November 26, 1900 discourse On Two Methods, and Jaurès' answer at the same meeting

- ^ Bon.

- ^ Yvert, Benoît, ed. (1990). Dictionnaire des ministres (1789–1989). Paris: Perrin. p. 483.

- ^ a b Willard, Claude (1991). Jules Guesde, l'apôtre et la loi, Les éditions ouvrières, coll. la part des hommes.

Sources

[edit]- Bon, Nicolas, "Midi 1907, l'histoire d'une révolte vigneronne", vin-terre-net.com (in French)

- Lafargue, Paul (September 1897), "Socialism in France 1874-1896", Nineteenth Century, translated by Aveling, retrieved 2018-01-28

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Guesde, Jules Basile". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 672–673.

Further reading

[edit]- Samuel Bernstein, "Jules Guesde, Pioneer of Marxism in France," Science and Society, vol. 4, no. 1 (Winter 1940), pp. 29–56. In JSTOR.

External links

[edit]- (in English) Guesde' texts at Marxist Internet Archives

- Archive of Jules Guesde Papers at the International Institute of Social History

- 1845 births

- 1922 deaths

- Politicians from Paris

- Writers from Paris

- Federation of the Socialist Workers of France politicians

- French Workers' Party politicians

- Socialist Party of France (1902) politicians

- French Section of the Workers' International politicians

- Government ministers of France

- Members of the 6th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic

- Members of the 9th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic

- Members of the 10th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic

- Members of the 11th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic

- Members of the 12th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic

- Members of Parliament for Nord

- French journalists

- Members of the International Workingmen's Association

- French male non-fiction writers