Groningen

Groningen

Grunn(en) (Gronings) | |

|---|---|

City and municipality | |

Gasunie building Grote Markt Square Groningen City Theater Aa Church/Korenbeurs | |

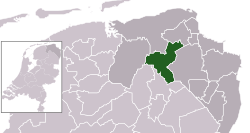

Location in Groningen | |

| Coordinates: 53°13′08″N 06°34′03″E / 53.21889°N 6.56750°E | |

| Country | |

| Province | Groningen |

| City Hall | Groningen City Hall |

| Government | |

| • Body | Municipal council |

| • Mayor | Koen Schuiling (VVD) |

| Area | |

• Municipality | 197.96 km2 (76.43 sq mi) |

| • Land | 185.60 km2 (71.66 sq mi) |

| • Water | 12.36 km2 (4.77 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 7 m (23 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 12 m (39 ft) |

| Population (January 1st 2023) | |

• Municipality | 238 147[1] |

| • Density | 1,257/km2 (3,260/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 216,655 |

| • Metro | 360,748 |

| Demonym(s) | Groninger, Stadjer |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postcode | 9700–9747 |

| Area code | 050 |

| Website | gemeente |

| |

| Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

Groningen (/ˈɡroʊnɪŋən/ GROH-ning-ən, UK also /ˈɡrɒnɪŋən/ GRON-ing-ən;[5][6] Dutch: [ˈɣroːnɪŋə(n)] ⓘ; Gronings: Grunn or Grunnen [ˈχrʏnn̩]) is the capital city and main municipality of Groningen province in the Netherlands. Dubbed the "capital of the north", Groningen is the largest place as well as the economic and cultural centre of the northern part of the country;[7][8] as of January 2023, it had 238,147 inhabitants, making it the sixth largest city/municipality in the Netherlands and the second largest outside the Randstad.

Groningen was established more than 980 years ago and gained city rights in 1245.[9] Due to its relatively isolated location from the then successive Dutch centres of power (Utrecht, The Hague, Brussels), Groningen was historically reliant on itself and nearby regions. As a Hanseatic city, it was part of the North German trade network, but later it mainly became a regional market centre. At the height of its power in the 15th century, Groningen could be considered an independent city-state and it remained autonomous until the late 18th century, when it was incorporated into the Napoleonic Batavian Republic.[10]

Today Groningen is a university city, home to some of the country's leading higher education institutes; University of Groningen (Rijksuniversiteit Groningen), which is the Netherlands's second oldest university, and Hanze University of Applied Sciences (Hanzehogeschool Groningen).[11] Students comprise an estimated 25% of its total population, making it the country's demographically youngest city.[12]

Etymology

[edit]The origin and meaning of 'Groningen' and its older variant, 'Groeningen', are uncertain. A folk origin story relates the idea that, in 453 BC, exiles from Troy who were guided by a mythical figure called Gruno (or Grunius, Gryns or Grunus), along with a group of Phrygians from Germany, founded a settlement in what is now Groningen, and built a castle on the bank of the Hunze, which they called 'Grunoburg', and which was later destroyed by the Vikings.[13][14]

One modern theory is that 'Groningen' meant 'among the people of Groni' ('Groningi' and 'Groninga' in the 11th century), derived from Gronesbeke, which was the old name for a small lake near the Hunze (on the northern border of Zuidlaarderveen).[15] As the name Grone (variant Groene) is an old Frisian personal name, the origin may very well be in a settlement originally founded by the family of Grone and their followers, which in Frisian would be called Groninga. Another theory is that the name was derived from the word groenighe, meaning 'green fields'.[14]

In Frisian, it is called Grins.[16] In Groningen province, it is called Groot Loug. Regionally, it is often simply referred to as Stad (the "city"),[17][18] and its inhabitants are referred to as Stadjers or Stadjeder.[19] The Dutch sometimes refer to it as "the Metropolis of the North",[20] or Martinistad (after the Martinitoren tower).[20]

History

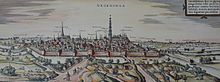

[edit]The city was founded at the northernmost point of the Hondsrug area.[21] While the oldest document referring to Groningen's existence dates from 1040, the area was occupied by Anglo-Saxons centuries prior.[22] The oldest archaeological evidence of a settlement in the region stems from around 3950–3650 BC,[23] and the first major settlement in Groningen trace back to the year 3 AD.[24]

In the 13th century Groningen was an important trade centre and its inhabitants built a city wall to underline its authority.[25] The city had a strong influence on its surrounding lands and the Gronings dialect became common.[26] The city's most influential period was at the end of the 15th century, when the nearby province of Friesland was administered from Groningen.[27] During these years the Martinitoren was built which is considered to be the city's most significant landmark.[28]

In 1536, Groningen accepted Emperor Charles V, the King of Spain and the Habsburg ruler of the other Netherlands as its ruler, thus ending the region's autonomy.[29] The city was captured in the Siege of Groningen (1594) by the Dutch and English forces led by Maurice of Nassau.[30] After the siege, the city and the province joined the Dutch Republic.[31]

During the 17th century, Groningen served as a crucial hub for the Dutch West India Company (WIC). This powerful trading company was responsible for maritime trade, colonization, and the transportation of goods and people.

The WIC transported over 300,000 slaves from the African coast to the Dutch colonies between 1621 and 1792. Warships like the Groeningen sailed from Groningen’s shipyards to Africa’s west coast, carrying enslaved Africans to plantations in Brazil, Suriname, and the Antilles.[32] These same ships returned to Europe laden with valuable commodities such as sugar, coffee, and tobacco.

The University of Groningen was founded in 1614 with initial course offerings in law, medicine, theology and philosophy.[33] During this period the city expanded rapidly and a new city wall was built.[34]

The Siege of Groningen (1672) led by the bishop of Münster, Bernhard von Galen during the Third Anglo-Dutch War failed and the city walls resisted;[35] an event that is celebrated annually with music and fireworks on 28 August as "Gronings Ontzet" or "Bommen Berend" ("Bombing Bernard").[36][37] In the early 19th century when the kingdom of Holland under king Jerôme Bonaparte was founded, Groningen was integrated into the French system of administration, and then annexed in 1811 into the French Empire under emperor Napoleon I (until 1813). During the French administration of the area, Groningen was called Groningue.[38]

During World War II, the main square and the Grote Markt were largely destroyed in the Battle of Groningen in April 1945.[34] However, the church Martinitoren, the Goudkantoor, and the city hall were undamaged.[39]

Geography

[edit]There is a town named after Groningen in Saramacca District, Suriname. a former Dutch colony. It was named after the hometown of Dutch governor-general of Suriname Jan Wichers, who established the town as a fort in 1790.

Canals

[edit]Numerous canals (grachten) surround the city, locally called diep. The major canals that travel from the city are the Van Starkenborghkanaal, Eemskanaal, and Winschoterdiep. Groningen’s canals, no longer used for commercial goods transport, were once vital hubs in trade and transport. The rivers crossing close to the Binnenstad have been used for trade for at least a thousand years. The Dutch West India Company and foreign investors established their Groningen headquarters in Reitemakersrijge. Additional warehouses were strategically built along the canals at Noorderhaven to store colonial produce.[32] These warehouses often held goods obtained from plantations in the Dutch colonies.

Climate

[edit]Groningen has an oceanic temperate climate, like all of the Netherlands, although slightly colder in winter than other major cities in the Netherlands due to its northeasterly position.[40] Weather is influenced by the North Sea to the north-west and its prevailing north-western winds and gales.[41]

Summers are somewhat warm and humid.[42] Temperatures of 30 °C (86 °F) or higher occur sporadically; the average daytime high is around 22 °C (72 °F). Very rainy periods are common, especially in spring and summer. Average annual precipitation is about 800 mm (31 in). Annual sunshine hours vary, but are usually below 1600 hours, giving much cloud cover similar to most of the Netherlands. Climate in this area has mild differences between highs and lows, and there is adequate rainfall year-round. The Köppen Climate Classification subtype for this climate is "Cfb". (Marine West Coast Climate/Oceanic climate).[43]

Winters are cool; on average above freezing, although frosts are common during spells of easterly winds.[44] Night-time temperatures of −10 °C (14 °F) or lower are not uncommon during cold winter periods. The lowest temperature ever recorded is −26.8 °C (−16.2 °F) on 16 February 1956. Snow often falls, but rarely stays long due to warmer daytime temperatures, although white snowy days happen every winter.[45]

| Climate data for Groningen (Groningen Airport Eelde), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1906–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.5 (58.1) |

18.9 (66.0) |

24.0 (75.2) |

28.8 (83.8) |

32.8 (91.0) |

33.8 (92.8) |

36.9 (98.4) |

36.3 (97.3) |

32.6 (90.7) |

27.4 (81.3) |

19.4 (66.9) |

15.4 (59.7) |

36.9 (98.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

6.0 (42.8) |

9.5 (49.1) |

14.2 (57.6) |

17.6 (63.7) |

20.4 (68.7) |

22.7 (72.9) |

22.6 (72.7) |

19.0 (66.2) |

14.2 (57.6) |

9.0 (48.2) |

5.9 (42.6) |

13.9 (57.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.8 (37.0) |

3.0 (37.4) |

5.5 (41.9) |

9.0 (48.2) |

12.5 (54.5) |

15.4 (59.7) |

17.5 (63.5) |

17.3 (63.1) |

14.1 (57.4) |

10.3 (50.5) |

6.3 (43.3) |

3.5 (38.3) |

9.8 (49.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 0.1 (32.2) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

1.4 (34.5) |

3.7 (38.7) |

7.0 (44.6) |

9.9 (49.8) |

12.2 (54.0) |

11.9 (53.4) |

9.6 (49.3) |

6.3 (43.3) |

3.2 (37.8) |

0.8 (33.4) |

5.5 (41.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −22.0 (−7.6) |

−22.9 (−9.2) |

−18.4 (−1.1) |

−8.1 (17.4) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

0.1 (32.2) |

2.5 (36.5) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

−13.6 (7.5) |

−22.0 (−7.6) |

−22.9 (−9.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 72.7 (2.86) |

54.7 (2.15) |

54.1 (2.13) |

41.3 (1.63) |

57.9 (2.28) |

65.0 (2.56) |

85.0 (3.35) |

77.8 (3.06) |

75.4 (2.97) |

71.4 (2.81) |

70.0 (2.76) |

79.4 (3.13) |

804.7 (31.68) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 13.3 | 10.6 | 10.3 | 8.5 | 9.5 | 10.3 | 11.7 | 11.5 | 11.1 | 12.1 | 13.2 | 14.0 | 136.1 |

| Average snowy days | 8 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 33 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 90 | 88 | 85 | 79 | 79 | 81 | 82 | 83 | 86 | 89 | 91 | 92 | 85 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 60.7 | 86.1 | 139.0 | 188.7 | 218.0 | 198.6 | 212.3 | 196.3 | 150.7 | 112.9 | 63.4 | 56.1 | 1,682.8 |

| Source: Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute[46][47] | |||||||||||||

Economy

[edit]Hotel and catering industries constitute a significant part of the economy in Groningen.[48] Focus on business services has increased over time and areas such as IT, life sciences, tourism, energy, and environment have developed.[49]

Until 2008 there were two major sugar refineries within the city. The Suiker Unie plant was constructed in the outskirts of Groningen, but became a part of the city due to expansion. The factory had 98 employees before it was closed in 2008 due to a reduction in demand.[50] As of 2017, CSM Vierverlaten in Hoogkerk remains the only beet sugar production plant in the city.[51] Other notable companies from Groningen include publishing company Noordhoff Uitgevers,[52] tobacco company Niemeyer,[53] health insurance company Menzis,[54] distillery Hooghoudt,[27] and natural gas companies GasUnie and GasTerra.[55]

Demographics

[edit]Immigration

[edit]| Country/territory | Population |

|---|---|

| 175,249 | |

| 6,427 | |

| 5,847 | |

| 3,959 | |

| 3,401 | |

| 2,321 | |

| 2,172 | |

| 1,774 | |

| 1,768 | |

| 1,401 | |

| 1,391 | |

| 1,266 | |

| 1,157 | |

| 1,050 | |

| Other | 11,992 |

As of 2020, Groningen had a total population of 232,874 people.

| 2020[57] | Numbers | % |

|---|---|---|

| Dutch natives | 175,249 | 75.2% |

| Western migration background | 29,365 | 12.6% |

| Non-Western migration background | 28,260 | 12.1% |

| Indonesia | 5,847 | 2.51% |

| Netherlands Antilles and Aruba | 3,959 | 1.7% |

| Suriname | 3,401 | 1.46% |

| Turkey | 1,774 | 0.76% |

| Morocco | 1,266 | 0.54% |

| Total | 232,874 | 100% |

This section needs expansion with: prose, examples, and citations. You can help by adding to it. (July 2018) |

Religion

[edit]The majority of people in Groningen, slightly more than 70%, are non-religious.[58] With 25.1%, the largest religion in Groningen is Christianity.

Religions in Groningen (2013)[59]

Population growth

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1400 | 5,000 | — |

| 1560 | 12,500 | +0.57% |

| 1600 | 16,600 | +0.71% |

| 1721 | 20,680 | +0.18% |

| 1770 | 23,296 | +0.24% |

| 1787 | 22,000 | −0.34% |

| 1795 | 23,770 | +0.97% |

| Source: Lourens & Lucassen 1997, pp. 30–31 | ||

The municipality of Groningen has grown rapidly. In 1968 it expanded by mergers with Hoogkerk and Noorddijk,[60] and in 2019 it merged with Haren and Ten Boer.[49] All historical data are for the original city limits, excluding Hoogkerk, Noorddijk, Haren and Ten Boer.

It has a land area of 168.93 km2 (65.22 sq mi), and a total area, including water, of 180.21 km2 (69.58 sq mi). Its population density is 1,367 residents per km2 (3,540 per square mile). On 1 January 2019, it was merged with the municipalities of Ten Boer and Haren. The Groningen-Assen metropolitan area has about half a million inhabitants.

Culture

[edit]Groningen is nationally known as the "Metropolis of the North".[61] The city is regarded as the main urban centre of the Northern part of the country, particularly in the fields of education, business,[62] music and other arts.[63] It is also known as "Martinistad", referring to the tower of the Martinitoren,[20] which is named after Groningen's patron saint Martin of Tours.[64] The large student population also contributes to the very diverse cultural scene for a city of its size.[20]

Since 2016 Groningen has been host of the International Cycling Film Festival, an annual film festival for bicycle related films. It takes place in the art house cinema of the old Roman Catholic Hospital.[65]

The first major international chess tournament after World War II was held in Groningen in 1946. The tournament, won by Mikhail Botvinnik of the USSR, was the first time the Soviet Union had sent a team to a foreign event. An international chess "Schaakfestival Groningen tournament" has been held in the city in most years since 1946.[66]

Museums

[edit]

Groningen is home to the Groninger Museum.[67] Its new building designed by Alessandro Mendini in 1994 echoes the Italian post-modern concepts and is notable for its futuristic and colourful style.[68][39] The city has a maritime museum, a university museum, a comics museum and a graphics museum.[69] Groningen is also the home of Noorderlicht, an international photographic platform that runs a photo gallery and organizes an international photo festival.[70] The Forum Groningen that opened in 2019 is a cultural center consisting of a museum, art cinema, library, bars, rooftop terrace and tourist information office.[71]

Theatre and music

[edit]

Groningen has a city theatre called the Stadsschouwburg, located on the Turfsingel,[72] a theatre and concert venue called Martini Plaza,[73] and a cultural venue on the Trompsingel, called the Oosterpoort.[74] Vera is located on the Oosterstraat,[75] the Grand Theatre on the Grote Markt,[76] and Simplon on the Boterdiep.[77] Several cafés feature live music, a few of which specialize in jazz music, including the Jazzcafe De Spieghel on the Peperstraat.[78] Groningen is the host city for Eurosonic Noorderslag, an annual music showcase event for bands from across Europe.[79]

Nightlife

[edit]Groningen's active nightlife depends largely on its student population, with the Grote Markt, Vismarkt, Poelestraat and Peperstraat crowded nightly, most bars not closing until five in the morning.[25] From 2005 to 2007, Groningen was named "best city centre" of the Netherlands.[80] Groningen has a red-light district, called Nieuwstad.[81]

Sports

[edit]

FC Groningen, founded in 1971, is the local football club, and as of 2000 they play in the Eredivisie, the highest football league of the Netherlands.[82] Winners of the KNVB Cup in the 2014–15 season,[83] their best Eredivisie result was in the 1990–91 season when they finished third.[84] Their current stadium which opened in January 2006 has 22,525 seats.[85][86] It is called the Hitachi Capital Mobility Stadion; it was known as the "Euroborg stadium" before 2016, and "Noordlease Stadion" from 2016 to 2018.[87]

American sports are fairly popular in Groningen; it has American football, baseball, and basketball clubs. Groningen's professional basketball club Donar play in the highest professional league, the Dutch Basketball League, and have won the national championship seven times.[88] The Groningen Giants are the American football team of the city who play in the premier league of the AFBN and are nicknamed as the "Kings of the North".[89]

The running event called 4 Miles of Groningen takes place in the city on the second Sunday of October every year with over 23,000 participants.[90] The 2002 Giro d'Italia began in Groningen, including the prologue and the start of the first stage.[91] The city hosted the start and finish of the fifth stage of the 2013 Energiewacht Tour.[92]

Education

[edit]

As of 2020, around 25% of the 230,000 inhabitants in Groningen are students. The city has the highest density of students and the lowest mean age in the Netherlands.[93]

There are also Middle Schools, such as H.N. Werkman College

The University of Groningen (in Dutch: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen), established in 1614 is the second oldest university in the Netherlands (after the University of Leiden).[94] The university educated the country's first female student, Aletta Jacobs,[95] the first Dutch national astronaut, Wubbo Ockels,[96] the first president of the European Central Bank, Wim Duisenberg,[52] and two Nobel laureates; Heike Kamerlingh Onnes (in Physics) and Ben Feringa (in Chemistry).[97][98] The university has about 31,000 students—22% of which are international.[99]

The Hanze University of Applied Sciences (in Dutch: Hanzehogeschool Groningen) was founded in 1986 and is more focused on the practical application of knowledge, offering bachelor and master courses in fields like Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Communication and Multimedia Design, and Renewable Energy.[100][101] With around 8.1% international students, Hanze hosts more than 28,000 students and is one of the largest universities of applied sciences by enrollment in the Netherlands.[102]

Politics

[edit]The Groningen municipal council has 45 members which, after the 2022 local elections, was made up as follows:[103]

| Party name | Seats |

|---|---|

| GroenLinks | 9 |

| PvdA | 6 |

| D66 | 5 |

| Party for the Animals | 4 |

| Stadspartij 100% voor Groningen | 4 |

| Socialist Party | 4 |

| VVD | 3 |

| Student en Stad | 3 |

| Christian Union | 2 |

| Christian Democratic Appeal | 2 |

| Party for the North | 2 |

| Party for Freedom | 1 |

From 2022, the ruling municipal coalition consisted of GroenLinks, PvdA, Party for the Animals, the Socialist Party and ChristenUnie.[105]

International relations

[edit]Groningen is twinned with the following cities:[106][107]

|

Groningen also has a trilateral partnership with the nearby northern German cities of Bremen and Oldenburg.[110]

Transport

[edit]Cycling and walking

[edit]

Groningen is known as the "World Cycling City"; around 57% of its residents use a bicycle for regular commute within the city.[111] In 2000, Groningen was chosen as the Fietsstad 2002, the top cycle-city in the Netherlands for 2002.[112] Similar to most Dutch cities, Groningen has developed to accommodate a large number of cyclists.[113] An extensive network of bike paths were planned to make it more convenient to cycle to various destinations instead of taking a car.[114]

The city has segregated cycle-paths, public transport, and a large pedestrianised zone in the city centre.[115] Groningen's city centre was remodeled into a "pedestrian priority zone" to promote walking and biking.[116] This was achieved by applying the principle of filtered permeability—the network configuration favours active transportation and selectively "filters out" traveling in a car by reducing the number of streets that run through the centre.[117] The streets that are discontinuous for cars connect to a network of pedestrian and bike paths which permeate the entire centre.[118] In addition, these paths go through public squares and open spaces, increasing aesthetic appeal and encouraging participation.[119] The logic of filtering a mode of transport is fully expressed in a comprehensive model for laying out neighbourhoods and districts—the fused grid.[120]

Public transport

[edit]Trains

[edit]

Groningen railway station (in Dutch: Hoofdstation) is the main railway station and has regular services to most of the major cities in the country.[39] The city's remaining two railway stations are Europapark and Noord.[121][122]

Groningen has six railway routes:[123]

- Groningen – Delfzijl

- Groningen – Roodeschool / Eemshaven

- Groningen – Leeuwarden

- Groningen – Veendam

- Groningen – Weener / Leer

- Groningen – Meppel / Zwolle

On those six routes, ten lines stop at:[123]

- Groningen – Groningen North – Sauwerd – Bedum – Stedum – Loppersum – Appingedam – Delfzijl West – Delfzijl

- Groningen – Groningen North – Sauwerd – Winsum – Baflo – Warffum – Usquert – Uithuizen – Uithuizermeeden – Roodeschool – (Low Service) Eemshaven

- Groningen – Zuidhorn – Grijpskerk – Buitenpost – De Westereen – Feanwâlden – Hurdegaryp – Leeuwarden Camminghaburen – Leewarden

- Groningen – Buitenpost – Leewarden

- Groningen – Groningen Europapark – Kropswolde – Martenshoek – Hoogezand-Sappemeer – Sappemeer oost – Zuidbroek – Veendam

- Groningen – Groningen Europapark – Kropswolde – Martenshoek – Hoogezand-Sappemeer – Sappemeer oost – Zuidbroek – Scheemda – Winschoten – (lower service) Bad Nieuweschans – Weener (Due to a broken bridge, trains do not go on to Leer. Take a bus from Groningen or Weener.)

- Groningen – Groningen Europapark – Haren – Assen – Beilen – Hoogeveen – Meppel – Zwolle

- Groningen – Assen – Zwolle – Amersfoort Centraal – Utrecht Centraal – Gouda – Rotterdam Alexander – Rotterdam Centraal

- Groningen – Assen – Zwolle – Lelystad Centrum – Almere Centrum – Amsterdam South – Schiphol – Leiden Centraal – Den Haag Centraal / The Hague Centraal

Buses

[edit]Direct bus routes from Groningen to Bremen, Hamburg, Berlin, and Munich are also available.

Motorways

[edit]The A28 motorway connects Groningen to Utrecht (via Assen, Zwolle and Amersfoort).[126] The A7 motorway connects it to Friesland and Zaandam (West), and Winschoten and Leer (East).[127]

Airport

[edit]

Groningen Airport Eelde is an international airport located near Eelde, in Drenthe, with scheduled services to Guernsey, Gran Canaria, Antalya, Crete, Mallorca & Bodrum.[128]

Notable people

[edit]

- Abel Janszoon Tasman (1603–1659), explorer, seafarer, merchant for the Dutch East India Company

- Albert Dominicus Trip van Zoudtlandt (1776–1835), lieutenant-general at the Battle of Waterloo

- Geert Adriaans Boomgaard (1788–1899), soldier, first validated supercentenarian

- Heike Kamerlingh Onnes (1853–1926), physicist, Nobel laureate

- Dirk Jan de Geer (1870–1960), statesman and Dutch Prime Minister (1926–29, 1939–40), advocated peace settlement between the Netherlands and Nazi Germany in 1940

- A. W. L. Tjarda van Starkenborgh Stachouwer (1888–1978), last colonial Governor-General of the Netherlands East Indies

- Michel Velleman (1895–1943), Jewish magician

- Jan Wolthuis (1903–1983), lawyer and collaborator, active in far-right politics after WWII

- Esmée van Eeghen (1918–1944), Dutch resistance member executed by the Nazis in Paddepoel, Noorddijk

- Pete Hoekstra (born 1953), United States ambassador to the Netherlands, former Republican member of Congress representing Michigan's 2nd congressional district

- Gerard Kemkers (born 1967), speed skating bronze medalist at 1988 Winter Olympics

- Anda Kerkhoven (1919–1945), Dutch resistance member executed by the Nazis near Glimmen

- Bauke Mollema (born 1986), cyclist

- Kim Feenstra (born 1985), model

- Ben Woldring (born 1985), internet entrepreneur

- Luciano Valente (born 2003), professional footballer

- Noisia, music producers

- Vicetone, DJ and music producer duo

See also

[edit]- Sint Geertruidsgasthuis, a hofje in Groningen

- Hunze

References

[edit]- ^ "CBS Statline kerncijfers". cbs.nl.

- ^ "Burgemeester" [Mayor] (in Dutch). Gemeente Groningen. Archived from the original on 22 December 2013. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ^ "Kerncijfers wijken en buurten 2020" [Key figures for neighbourhoods 2020]. StatLine (in Dutch). CBS. 24 July 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ "Postcodetool for 9712HW". Actueel Hoogtebestand Nederland (in Dutch). Het Waterschapshuis. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ^ "Groningen". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ "Groningen" Archived 1 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine (US) and "Groningen". Oxford Dictionaries UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. n.d. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ "Minicruises to Groningen". Holland Norway Lines. Archived from the original on 15 September 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ "Groningen: Small City, Full of Life". University of Groningen. 19 September 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ "Stadsrechten in Groningen en Drenthe". 24 July 2011. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ van de Broek, Jan (2007). Groningen, een stad apart : over het verleden van een eigenzinnige stad (1000-1600). Assen: Koninklijke Van Gorcum. p. 71.

- ^ administrator. "Study in Groningen, The Netherlands". Study In Holland. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ "Groningen: student city". Groningen.nl. Archived from the original on 9 August 2023. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ De Navorscher: Een middel tot gedachtenwisseling en letterkundig verkeer, tusschen allen die iets weten: iets te vragen hebben, of iets kunnen oplossen ... (in Dutch). J.C. Loman, Jr. 1855. pp. 44–45.

- ^ a b John Lothrop Motley (1867). History of the United Netherlands, from the Death of William the Silent to the Synod of Dort: With a Full View of the English-Dutch Struggle Against Spain, and of the Origin and Destruction of the Spanish Armada. John Murray. p. 270.

- ^ Nieuwe Groninger encyclopedie (in Dutch). REGIO-PRoject uitgevers. 1999. p. 317. ISBN 978-90-5028-132-4.

- ^ "Grins (II)”, in Wurdboek fan de Fryske taal (in Dutch), 2011

- ^ Onze taaltuin (in Dutch). Vol. 5–6. 1936. p. 187.

- ^ Helmer Molema (1887). Woordenboek der Groningsche volkstaal in de 19de eeuw (in Dutch). Mekel. p. 398.

- ^ Association for History and Computing. International Conference (1995). Structures and Contingencies in Computerized Historical Research: Proceedings of the IX International Conference of the Association for History & Computing, Nijmegen, 1994. Uitgeverij Verloren. p. 94. ISBN 90-6550-142-8.

- ^ a b c d Cliff Hague; Paul Jenkins (2005). Place Identity, Participation and Planning. Psychology Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-415-26242-2.

- ^ Rob Roggema (2 December 2012). Swarming Landscapes: The Art of Designing For Climate Adaptation. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 8. ISBN 978-94-007-4378-6.

- ^ Pieter C. van der Kruit (18 November 2014). Jacobus Cornelius Kapteyn: Born Investigator of the Heavens. Springer. p. 85. ISBN 978-3-319-10876-6.

- ^ Alistair Barclay; David Field; Jim Leary (30 April 2020). Houses of the Dead. Oxbow Books. p. 270. ISBN 978-1-78925-411-2.

- ^ A.A. Balkema (1982). Palaeohistoria. Vol. 32. A.A. Balkema. p. 111. ISBN 9789054101369.

- ^ a b Martin Dunford; Phil Lee (1 March 2007). The Rough Guide to the Netherlands. Rough Guides Limited. pp. 556–575. ISBN 978-1-84836-843-9.

- ^ Leiv E. Breivik; Ernst H. Jahr (1 June 2011). Language Change: Contributions to the Study of its Causes. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 267–270. ISBN 978-3-11-085306-3.

- ^ a b DK Eyewitness (7 May 2020). DK Eyewitness The Netherlands. Dorling Kindersley Limited. pp. 448–456. ISBN 978-0-241-46459-5.

- ^ E.O. van der Werff, Martini. Kerk en toren. Assen, 2003, p. 53; F. Westra, Martinitoren. Groningen, 2009, p. 29. According to an improbable myth, the tower would have been 127 m high

- ^ Clement Cruttwell (1808). The New Universal Gazetteer, or, Geographical Dictionary: Containing a Description of All the Empires, Kingdoms, States, Provinces, Cities, Towns, Forts, Seas, Harbours, Rivers, Lakes, Mountains, and Capes in the Known World ; with the Government, Customs, Manners, and Religion of the Inhabitants ... ; with Twenty-eight Whole Sheet Maps. Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orme. p. 331.

- ^ J. Willoughby Rosse; John Blair (1859). An Index of Dates: Comprehending the Principal Facts in the Chronology and History of the World, from the Earliest to the Present Time. Alphabetically Arranged. Being a Complete Index to the Enlarged Edition of Blair's Chronological Tables. Bell & Daldy. p. 871.

- ^ R. Prokhovnik (31 March 2004). Spinoza and Republicanism. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-230-00090-2.

- ^ a b "Groningen's links to the Dutch Slave Trade". The Northern Times. 25 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ "Groningen, University of". The Independent. 22 March 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ a b Major Jeffrey D. Noll U.S. Army (15 August 2014). Restraint In Urban Warfare: The Canadian Attack On Groningen, Netherlands, 13-16 April 1945. Lucknow Books. pp. 32–66. ISBN 978-1-78289-810-8.

- ^ Wouter Troost (2005). William III the Stadholder-king: A Political Biography. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-7546-5071-3.

- ^ Society of Archer-Antiquaries (1969). Journal of the Society of Archer-Antiquaries. Society of Archer-Antiquaries. p. 126.

- ^ Groningen tourism site Archived 2008-12-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Conrad Malte-Brun (1834). A System of Universal Geography: Or A Description of All the Parts of the World, on a New Plan, According to the Great Natural Divisions of the Globe. S. Walker. p. 1095.

- ^ a b c G.J. Ashworth (22 November 2017). The Construction of Built Heritage: A North European Perspective on Policies, Practices and Outcomes. Taylor & Francis. pp. 87–96. ISBN 978-1-351-74212-2.

- ^ "The weather and surroundings of Groningen". FutureLearn. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ J. Smith Homans (1859). A Cyclopedia of Commerce and Commercial Navigation, with Maps and Engravings: To which is Now Added a Chart of the Bay and Harbor of New York, with the Soundings of East River, North River, Harlem River, Newark Bay, and New York Bay. Harper & Brothers. pp. 970–990.

- ^ Popular encyclopedia (1879). The popular encyclopedia; or, 'Conversations Lexicon': [ed. by A. Whitelaw from the Encyclopedia Americana]. pp. 468–470.

- ^ "Groningen, Netherlands Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ William GUTHRIE (of Brechin.); James FERGUSON (F.R.S.); William Herschel (1794). A new geographical, historical, and commercial Grammar. Fourteenth edition, illustrated with a correct set of maps. pp. 449–451.

- ^ The Meteorological Magazine. Vol. 119. H.M. Stationery Office. 1990. p. 28.

- ^ "Klimaattabel Eelde, langjarige gemiddelden, tijdvak 1981–2010" (PDF). Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ "Eelde, gehomogeniseerde langjarige extremen, tijdvak 1906–2022". Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ "Number of overnight tourists up to 46 million in 2019". Statistics Netherlands. 9 March 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ a b OECD (31 March 2020). OECD Urban Studies The Circular Economy in Groningen, the Netherlands. OECD Publishing. pp. 14–24. ISBN 978-92-64-72442-6.

- ^ "Suiker Unie to Concentrate Sugar Production in Dinteloord and Hoogkerk". FoodIngredientsFirst.com. CNS Media. 17 January 2008. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "CSM beet plant a victim of EU sugar reform". ConfectioneryNews. 16 March 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ a b Joop W. Koopmans (5 November 2015). Historical Dictionary of the Netherlands. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 67–100. ISBN 978-1-4422-5593-7.

- ^ International Brands and Their Companies. Gale Research. 1991. p. 641. ISBN 978-0-8103-6946-7.

- ^ Sjors van Leeuwen (2007). Zorgmarketing in de praktijk (in Dutch). Uitgeverij Van Gorcum. p. 11. ISBN 978-90-232-4325-0.

- ^ Andrew C. Inkpen; Michael H. Moffett; Kannan Ramaswamy (14 June 2017). The Global Oil & Gas Industry: Stories From the Field. PennWell Corporation. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-1-59370-381-3.

- ^ "CBS StatLine – Bevolking; leeftijd, herkomstgroepering, geslacht en regio, 1 januari". Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ "CBS Statline". opendata.cbs.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- ^ "De religieuze kaart van Nederland, 2010-2015" (PDF). Statistics Netherlands. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ "Kerkelijkheid en kerkbezoek, 2010/2013". Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. 2 October 2014.

- ^ Historisch Genootschap te Groningen (1987). De Historie herzien: vijfde bundel "Historische avonden" (in Dutch). Uitgeverij Verloren. p. 73. ISBN 90-6550-309-9.

- ^ Mah, Kenny (30 September 2018). "Dutch haven: A day in Groningen". Malay Mail. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Erdener Kaynak; Muzaffer Uysal (12 November 2012). Global Tourist Behavior. Routledge. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-136-58641-5.

- ^ "Culture". GroningenLife!. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Hendrik Jan Willem Drijvers; Alasdair A. MacDonald (1995). Centres of Learning: Learning and Location in Pre-Modern Europe and the Near East. BRILL. p. 326. ISBN 90-04-10193-4.

- ^ "What, where, when: New tips for Groningen and Leeuwarden". The Northern Times. Persbureau Tammeling BV. 31 May 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ "Groningen (1946)". chessgames.com. 1 January 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Marietta de Vries (2010). Present. 010 Publishers. p. 278. ISBN 978-90-6450-708-3.

- ^ Fred Maidment (November 2000). International Business: 01/02. McGraw-Hill/Dushkin. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-07-243344-9.

- ^ The north and the Frisian Islands Rough Guides Snapshot Netherlands (includes Leeuwarden, Harlingen, Hindeloopen, Makkum, Sneek and Groningen). Rough Guides Limited. 25 April 2013. pp. 29–36. ISBN 978-1-4093-3543-6.

- ^ Athina Karatzogianni (17 June 2013). Violence and War in Culture and the Media: Five Disciplinary Lenses. Routledge. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-136-50021-3.

- ^ Rough Guides (1 March 2019). The Rough Guide to the Netherlands (Travel Guide eBook). Apa Publications (UK) Limited. p. 355. ISBN 978-1-78919-527-9.

- ^ Jeanette M. L. den Toonder; Bettina van Hoven (2012). Re-exploring Canadian Space. Barkhuis. p. 13. ISBN 978-94-91431-05-0.

- ^ Gazaleh-Weevers, Sheila; Shirley Agudo; Connie Moser (June 2007). Here's Holland. Eburon Uitgeverij B.V. p. 261. ISBN 978-90-5972-141-8.

- ^ Jason Toynbee; Byron Dueck (31 March 2011). Migrating Music. Routledge. p. 371. ISBN 978-1-136-90093-8.

- ^ Living Blues (42-44 ed.). Living Blues Publications. 1979. p. 16.

- ^ Karelse Van der Meer; Harm Tilman; De Zwarte Hond; Raimond Wouda (2005). Dutch Realist. NAi Publishers. p. 187. ISBN 978-90-5662-405-7.

- ^ Martin Dunford; Jack Holland; Phil Lee (2000). The Rough Guide to Holland. Rough Guides. p. 256. ISBN 978-1-85828-541-2.

- ^ Martin Dunford; Jack Holland; Phil Lee (1997). Holland. Rough Guides. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-85828-229-9.

- ^ "About Eurosonic Noorderslag". Eurosonic Noorderslag. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ "Winnaars 2005 – 2007 -- Verkiezing Beste Binnenstad" [Winners 2005 – 2007 -- Election Best City Centre] (in Dutch). debestebinnenstad.nl. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ^ Wind, Chris (13 February 2015). "Life behind red lights in Groningen". HanzeMag. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ "Standings". eredivisie.nl. Eredivisie. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ "FC Groningen pakt eerste KNVB-beker in clubhistorie ten koste van PEC – NU – Het laatste nieuws het eerst op NU.nl". nu.nl (in Dutch). 4 May 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ "Netherlands 1990/91". The Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ 10 million Euro orders for Olympic Stadium in Berlin and Euroborg Stadium in Groningen Archived 28 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine Imtech, 8 April 2004

- ^ "Club Info – FC Groningen". FC Groningen (in Dutch). 27 October 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ "Naam stadion FC Groningen gaat veranderen in Hitachi Stadion". NU. 28 June 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ "Landskampioenen, bekerwinnaars en competitiewinnaars" (in Dutch). J-dus.com. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Steven W. Coutinho (24 May 2018). Breaking Rank: How to lead change when yesterday's stories limit today's choices. Steven Coutinho. pp. 285–295. GGKEY:DZLXX5LE9CR.

- ^ "4 Mile of Groningen". Campus Groningen. 14 October 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ Jones, Jeff. "85th Giro d'Italia (GT)". cyclingnews.com. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ "Technical Guide Elite" (PDF). energiewachttour.nl. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ^ "Groningen: Student City". groningen.nl. Accord of Groningen. Archived from the original on 9 August 2023. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ Arthur Joseph van Essen (11 November 2013). E. Kruisinga: A Chapter in the History of Linguistics in the Netherlands. Springer. p. 37. ISBN 978-94-017-5618-1.

- ^ Jacobs, Aletta (1996). Feinberg, Harriet (ed.). Memories: My Life as an International Leader in Health, Suffrage, and Peace. Translated by Wright, Annie (English ed.). New York, New York: Feminist Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-558-61138-2.

- ^ European Space Agency (2014). Bulletin Agence Spatiale Européenne (157-160 ed.). ESA Publications Division. p. 84.

- ^ Arun Agarwal (2008). Nobel Prize Winners in Physics. APH Publishing. p. 80. ISBN 978-81-7648-743-6.

- ^ Asymmetric oxidation of phenols. Atropisomerism and optical activity. Archived from the original on 6 January 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ "Key figures". rug.nl. University of Groningen. 14 July 2004. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ "History – Hanze University of Applied Sciences, Groningen". Hanze University of Applied Sciences. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ "Programmes". hanze.nl. Hanze University of Applied Sciences. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ "Facts & Figures". hanze.nl. Hanze University of Applied Sciences. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ "Groningen municipal election 2022". www.verkiezingsuitslagen.nl (in Dutch). 16 March 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ GemeenteOplossingen. "Raadsleden, Gemeente Groningen". gemeenteraad.groningen.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ "Coalitieakkoord | Gemeente Groningen". gemeente.groningen.nl. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ "Groningen – Partner Cities". 2008 Gemeente Groningen, Kreupelstraat 1,9712 HW Groningen. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ^ "Kadernota Internationalisering 2013–2016" (PDF). gemeente.groningen.nl (in Dutch). Groningen. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ "Twin Towns – Graz Online – English Version". graz.at. Archived from the original on 8 November 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ^ "Kaliningrad – Partner Cities". 2000–2006 Kaliningrad City Hall. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ^ "International relations and development cooperation - Senatskanzlei UNESCO-Welterbe Rathaus Bremen". www.rathaus.bremen.de. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Pooley, Colin G (21 August 2013). Promoting Walking and Cycling: New Perspectives on Sustainable Travel. Policy Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-4473-1010-5.

- ^ R Tolley (29 August 2003). Sustainable Transport. Elsevier. p. 522. ISBN 978-1-85573-861-4.

- ^ Melissa Bruntlett; Chris Bruntlett (28 August 2018). Building the Cycling City: The Dutch Blueprint for Urban Vitality. Island Press. pp. 43–55. ISBN 978-1-61091-879-4.

- ^ Annette Becker; Stefanie Lampe; Lessano Negussie; Peter Cachola Schmal (23 April 2018). Ride a Bike!: Reclaim the City. Birkhäuser. p. 12. ISBN 978-3-0356-1525-8.

- ^ The Environmental Assessment of Traffic Management Schemes: A Literature Review. Transport Research Laboratory. 1995. p. 49.

- ^ Timothy Beatley (26 September 2012). Green Urbanism: Learning From European Cities. Island Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-61091-013-2.

- ^ Paul Appleby (12 October 2012). Integrated Sustainable Design of Buildings. Routledge. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-136-53985-5.

- ^ Fiona Spotswood (26 February 2016). Beyond Behaviour Change: Key Issues, Interdisciplinary Approaches and Future Directions. Policy Press. pp. 102–104. ISBN 978-1-4473-1756-2.

- ^ Commission of the European Communities (1994). City and Environment. The Commission. p. 58. ISBN 978-92-826-5902-1.

- ^ Melia, S. (2012). Filtered and unfiltered permeability: The European and Anglo-Saxon approaches. Project, 4.

- ^ Halte Groningen Europapark Archived 7 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine (in Dutch), Stationsweb. Retrieved on 25 May 2015.

- ^ Station Groningen Noord Archived 21 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine (in Dutch), Stationweb. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ a b "Spoorkaart 2020: hier te downloaden" (in Dutch). Nieus. 23 January 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Rob van Der Bijl; Niels Van Oort; Bert Bukman (29 June 2018). Light Rail Transit Systems: 61 Lessons in Sustainable Urban Development. Elsevier Science. pp. 166–186. ISBN 978-0-12-814785-6.

- ^ a b c d e "OV in cijfersInteractieve lijnennetkaart" (in Dutch). OV-bureau Groningen Drenthe. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ DK Eyewitness (6 July 2017). DK Eyewitness The Netherlands. Dorling Kindersley Limited. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-241-45190-8.

- ^ Vincent A. Dodd; Patrick M. Grace (1 June 1989). Agricultural Engineering: Proceedings of the 11th International Congress, Dublin, 4-8 September 1989. CRC Press. pp. 176–181. ISBN 978-90-6191-980-3.

- ^ "Destinations". Groningen Airport Eelde. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Lourens, Piet; Lucassen, Jan (1997). Inwonertallen van Nederlandse steden ca. 1300–1800. Amsterdam: NEHA. ISBN 9057420082.

External links

[edit]- Official website (in Dutch)