Government of Ireland Act 1920

| Name and origin | |

|---|---|

| Official name of legislation | Government of Ireland Act, 1920 |

| Location | Ireland into two autonomous regions Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland |

| Year | 1920 |

| Government introduced | Lloyd George (Liberal-Conservative coalition) |

| Parliamentary passage | |

| House of Commons passed? | Yes |

| House of Lords passed? | Yes |

| Royal Assent? | Yes |

| Defeated | |

| Which House | - |

| Which stage | - |

| Final vote | - |

| Date | - |

| Details of legislation | |

| Legislature type | 2 bicameral parliaments |

| Unicameral subdivision | none |

| Name(s) | upper: Senate; lower: House of Commons of Southern Ireland/Northern Ireland |

| Size(s) | Senate: NI 26; SI 61 Commons: NI 52; SI 128 |

| MPs in Westminster | 46 MPs |

| Executive head | Lord Lieutenant (later replaced by the Governor of Northern Ireland) |

| Executive body | Executive Committee of the Privy Council of Ireland, Privy Council of Northern Ireland |

| Prime Minister in text | none - but one evolved in Northern Ireland |

| Responsible executive | no - but de facto responsibility to House of Commons of Northern Ireland |

| Enactment | |

| Act implemented | Limited implementation in Southern Ireland, full in Northern Ireland |

| Succeeded by | Northern Ireland Act 1998 |

An Act to provide for the better government of Ireland, more usually the Government of Ireland Act 1920[1], sometimes called the Fourth Home Rule Act, was the Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which partitioned Ireland.

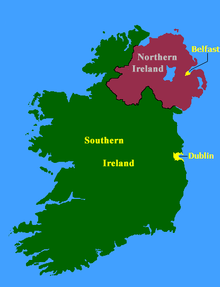

The Act provided for two separate sets of Home Rule institutions in Ireland: one covering a region that was to be named 'Northern Ireland' in the north-east of the island and the other covering the remainder of the island, which was termed Southern Ireland. The institutions of Northern Ireland functioned as intended until they were suspended by the UK government in 1972 following the outbreak of the Troubles. Southern Ireland never functioned as an operative political entity, and was superseded by the Irish Free State in 1922.

In historical terms, the Act was the legislative instrument that partitioned Ireland, though its provisions envisaged and attempted to provide for the eventual reunification of the island.

The Act was repealed in its entirety under the terms of the Northern Ireland Act 1998, after the Good Friday Agreement.

Background

The British Prime Minister was the author of the new Act.

Various attempts had been made to give Ireland limited regional self-government, known as Home Rule, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The First Home Rule Bill of 1886 was defeated in the House of Commons following intense Unionist and Orange Order opposition which caused a split in the Liberal Party, while the Second Home Rule Bill of 1893, having been passed by the Commons was vetoed by the House of Lords. The Third Home Rule Bill introduced in 1912 by the Irish Parliamentary Party could no longer be vetoed after the passing of the Parliament Act 1911 which removed the power of the Lords to veto bills. They could merely be delayed for two years.

Because of the continuing threat of civil war in Ireland, King George V called the Buckingham Palace Conference in July 1914 where Nationalist and Unionist leaders were invited to seek agreement, which failed. Controversy continued over the rival demands of Irish Nationalists, backed up by the Liberals (for all-Ireland home rule), and Irish Unionists, backed up by the Conservatives, for the exclusion of most or all of the province of Ulster. After an amending bill which allowed for Ulster to be temporarily excluded from the working of the Act, it passed onto the statute books and received Royal Assent immediately after the outbreak of World War I. The Act's implementation was suspended until after what was expected to be a short European war.

Long's committee

Two attempts were made by the Prime Minister H. H. Asquith during World War I to implement the Third Home Rule Act, first in May 1916 which failed on reaching agreement with Unionist Ulster, then again in 1917 with the calling of the Irish Convention chaired by John Redmond. It consisted of Nationalist and Unionist respresentatives who, by April 1918, only succeeded in agreeing a report with recommendations for an 'understanding' on the conflicting issues.

A delay ensued because of the ending of World War I, the Paris Peace Conference, 1919 and the Treaty of Versailles that was signed off in June. Starting in September 1919, with the Government, now led by David Lloyd George, committed under all circumstances to implementing Home Rule, the British cabinet's Committee for Ireland, under the chairmanship of former Ulster Unionist Party leader Walter Long, pushed for a radical new idea. Long proposed the creation of two Irish home rule entities, Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland, each with unicameral parliaments. The House of Lords amended the old Bill, accordingly, to create a new Bill with two bicameral parliaments, "consisting of His Majesty, the Senate of (Northern or Southern) Ireland, and the House of Commons of (Northern or Southern) Ireland."

The Bill's second reading debates in late March 1920 revealed that already a large number of Irish MPs present felt that the proposals were unworkable.[2][3]

After considerable delays in debating the financial aspects of the measure, the substantive third reading of the Bill was approved by a large majority on 11 November 1920. A considerable number of the Irish MPs present voted against the Bill, including Southern Unionists such as Maurice Dockrell, and Nationalists like Joe Devlin.[4] (The large majority of Irish MPs did not vote, having transferred their allegiance elsewhere).

Developments in Ireland

During the Great War Irish politics moved decisively in a different direction. Several events - including the Easter Rising of 1916, and the conscription crisis of 1918 - and the subsequent reaction of the British Government, had utterly altered the state of Irish Politics, and made Sinn Féin the dominant voice of Irish Nationalism. Sinn Féin, standing for 'an independent sovereign Ireland', had won seventy-three of the one hundred and five parliamentary seats on the island in the 1918 General Election and established its own unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) state, the Irish Republic with its own extra-legal parliament, Dáil Éireann.[5]

Also for a variety of reasons all the Ulster Unionist MPs at Westminster voted against the Act. They preferred that all or most of Ulster would remain fully within the United Kingdom, and only accepted the proposed northern Home Rule state as the second best option.

Thus, when the Act was passed on 23 December 1920 it was already out of touch with realities in Ireland. The long-standing demand for home rule had been replaced among Nationalists by a demand for complete independence. The Republic's army was waging the Irish War of Independence against British rule, which had reached a nadir in late 1920.

Two 'Home Rule' Irelands

The Act divided Ireland into two territories, Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland, each intended to be self-governing, except in areas specifically reserved to the Parliament of the United Kingdom: chief amongst these were matters relating to the Crown, to defence, foreign affairs, international trade, and currency.

"Southern Ireland" was to be all of Ireland except for "the parliamentary counties of Antrim, Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone, and the parliamentary boroughs of Belfast and Londonderry" which were to constitute "Northern Ireland". Northern Ireland as defined by the Act, amounting to six of the nine counties of Ulster, was seen as the maximum area within which Unionists could be expected to have a safe majority. This was in spite of the fact that counties Fermanagh and Tyrone had Catholic Nationalist majorities.

Structures of the governmental system

At the apex of the governmental system was to be the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, who would be the Monarch's representative in both of the Irish home rule regions. The system was based on colonial constitutional theories. Executive authority was to be vested in the crown, and in theory not answerable to either parliament. The Lord Lieutenant would appoint a cabinet that did not need parliamentary support. No provision existed for a prime minister.

Such structures matched the theory in the colonial constitutions in Canada and Australia, where in theory powers belonged to the governor-general and there was no theoretical responsibility to parliament. In reality, governments had long come to be chosen from parliament and to be answerable to it. Prime ministerial offices had come into de facto existence.[6] Such developments were also expected to happen in Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland, but technically were not required under the Act.

Potential for Irish unity

As well as sharing the same viceroy, a Council of Ireland was envisaged to co-ordinate matters of common concern to the two parliaments, with each parliament possessing the ability, in identical motions, to vote powers to the Council, which it was hoped would evolve into a single Irish parliament. Both parts of Ireland would continue to send a number of MPs to the Westminster Parliament. Elections for both lower houses took place in May 1921.

Aftermath

Northern Ireland

The Parliament of Northern Ireland came into being in June 1921. At its inauguration, in Belfast City Hall, King George V made a famous appeal for Anglo-Irish and north–south reconciliation. The speech, drafted by the government of David Lloyd George on recommendations from Jan Smuts[7] Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa, with the enthusiastic backing of the King, opened the door for formal contact between the British Government and the Republican administration of Eamon de Valera.

Though it was not originally desired by Unionists, the Act came to be revered by the Unionist community as the foundation of the union with Great Britain.[citation needed][dubious – discuss] Though it was superseded in large part, its repeal remained a matter of controversy until accomplished in the 1990s (under the provisions of the 1998 Belfast Agreement).[8]

All 128 MPs elected to the House of Commons of Southern Ireland in 1921 were returned unopposed, and 124 of them, representing Sinn Féin, declared themselves TDs (Irish for Dáil Deputies) and assembled as the Second Dáil of the Irish Republic.

With only the four Unionist MPs (all representing graduates of the Irish Universities) and 15 appointed senators turning up for the state opening of the Parliament of Southern Ireland at the Royal College of Science in Dublin (now Government Buildings) in June 1921, the new legislature was suspended. Southern Ireland was ruled, for the time being, directly from London as it had been before the Government of Ireland Act.

The Provisional Government of Southern Ireland was constituted on 14 January 1922 “at a meeting of members of the Parliament elected for constituencies in Southern Ireland”. That meeting was not convened as a meeting of the House of Commons of Southern Ireland nor as a meeting of the Dáil. Instead, it was convened by Arthur Griffith as “Chairman of the Irish Delegation of Plenipotentiaries” (who had signed the Anglo Irish Treaty) under the terms of the Treaty.[9] Notably it was not convened by Lord Fitzalan, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland who under the Government of Ireland Act was the office-holder with the entitlement to convene a meeting of the House of Commons of Southern Ireland.

Following elections, in June 1922, that created the Third Dáil, the Parliament of the United Kingdom and the Third Dáil enacted a new constitution for the Irish Free State which came into being on 6 December 1922.

Consequences

The Treaty provided for the ability of Northern Ireland's Parliament, by formal address, to opt out of the new Irish Free State, which was a foregone conclusion. An Irish Boundary Commission was set up to redraw the border between the new Irish Free State and Northern Ireland, but it remained unchanged in return for financial concessions, and the British and Irish governments agreed to suppress its report. The Council of Ireland never functioned as hoped, (as an embryonic all-Ireland parliament), as the new governments decided to find a better mechanism in January 1922.[10]

In the aftermath of the creation of the Irish Free State, the Irish Free State (Consequential Provisions) Act adjusted the Northern Ireland system of government slightly to cover the failure of Southern Ireland to function. The office of Lord Lieutenant was abolished and replaced by the Governor of Northern Ireland.

Repeal

The 1920 Act was repealed in its entirety under the terms of the Northern Ireland Act 1998, after the Belfast Agreement. In the republic, the Statute Law Revision Act 2007 repealed the Act 70 years after the republic's Constitution of Ireland replaced the Constitution of the Irish Free State in 1937.[11]

See also

- Second Dáil

- Parliament of Southern Ireland

- Parliament of Northern Ireland

- Unionists (Ireland)

- Irish Government Bill 1886 (First Irish Home Rule Bill)

- Irish Government Bill 1893 (Second Irish Home Rule Bill)

- Government of Ireland Act 1914 (Third Irish Home Rule Bill)

- Government of Ireland Act 1920 (Parliamentary and Dáil constituencies)

Further reading

- Robert Kee, The Green Flag: A History of Irish Nationalism (2000 edition, first published 1972), ISBN 0-14-029165-2.

References and footnotes

- ^ The formal citation is 10 & 11 Geo. 5 c. 67.

- ^ Hansard debate on the Bill, 29 Mar 1920

- ^ Hansard debate 31 Mar 1920

- ^ Hansard debate of 11 November 1920

- ^ Dáil Éireann, after a number of meetings, was declared illegal in September 1919 by the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. His declaration did not diminish Irish support for the new assembly and its republic.

- ^ A prime minister of Canada had come into existence within a decade of colonial rule in Canada, while in Australia a prime minister appeared in the system of government from the moment the Commonwealth of Australia came into being.

- ^ Jan Smuts was one of the best Boer commanders of the Second Boer War. His deep Commando raids into Cape Province caused considerable embarrassment and difficulties for the British Army. After the war he decided that his future and that of South Africa lay in reconciliation between Afrikaner and the British. In 1914 at the start of World War I the Boer "bitter enders" rose against the government in the Boer Revolt and allied themselves with their old supporter Germany. General Smuts played an important part in crushing the rebellion and defeating the Germans in Africa, before fighting on the Western Front. The South African establishment, of which Smuts was a part, in contrast to the British establishment in 1916, was lenient to the leaders of the revolt, who were fined and spent two years in prison. After this revolt and lenient treatment the "bitter enders" contented themselves with working within the system. It was his experience of the Boer–British rapprochement which he was able to bring to the attention of the British government as an alternative to confrontation.

- ^ Alvin Jackson, Home Rule - An Irish History, Oxford University Press, 2004, pp368-370.

- ^ This followed discussions between the Irish Treaty delegation and the British Government over who had authority to convene the “meeting”.

- ^ Text of the "Craig-Collins Pact, art 4., 23 Jan 1922

- ^ Irish Times 10 January 2007, p4.