Glenn Miller Orchestra

Glenn Miller and His Orchestra | |

|---|---|

Glenn Miller and His Orchestra, on the set of Sun Valley Serenade, 1941 | |

| Background information | |

| Genres | Dance band, Swing |

| Years active | 1938–1942 |

| Labels | |

| Past members | see members section |

| Website | www |

Glenn Miller and His Orchestra was an American swing dance band that was formed by Glenn Miller in 1938. Arranged around a clarinet and tenor saxophone playing melody, and three other saxophones playing harmony, the band became the most popular and commercially successful dance orchestra of the swing era and one of the greatest singles charting acts of the 20th century. As of 2025, Ray Anthony is the last surviving member of the orchestra.

Miller began professionally recording in New York City as a sideman in the hot jazz era of the late 1920s. With the arrival of virtuoso trombonists Jack Teagarden and Tommy Dorsey, Miller focused more on developing his arrangement skills. Writing for contemporaries and future stars such as Artie Shaw, and Benny Goodman, Miller gained prowess as an arranger by working in a variety of settings. Later, Miller largely improved his arranging and writing skills by studying under music theorist Joseph Schillinger.[1]

In February 1937, Miller started an orchestra that briefly made records for Decca. With this group, Miller used an arrangement he wrote for British bandleader Ray Noble's American band in an attempt to form a clarinet-reed sound. This style developed over time, and eventually became known as the Glenn Miller sound. Frustrated with his agency over playing inconsistent bookings and lacking broad radio exposure, Miller gave the band notice in December 1937. Less than three months later, he was looking for members and forming a new band.[1]

Miller began a partnership with Eli Oberstein, which led directly to a contract with Victor subsidiary Bluebird Records. Gaining notoriety at such engagements as the Paradise Restaurant and Frank Dailey–owned Meadowbrook and their corresponding nationwide broadcasts, Miller struck enormous popularity playing the Glen Island Casino in the summer of 1939. From late 1939 to mid-1942, Miller was the number-one band in the country, with few true rivals.[2] Only Harry James' band began to equal Miller's in popularity as he wound down his career in the wake of the Second World War.[1] The AFM strike prevented Miller from making any new recordings in the last two months of his band's existence, and they formally disbanded at the end of September 1942.

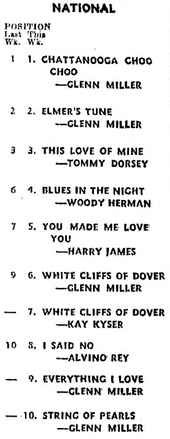

Miller's short-term chart successes have seldom been duplicated and his group's unprecedented dominance of early Your Hit Parade and Billboard singles charts resulted in 16 number-one singles and 69 Top Ten hits.

Musical success

[edit]Beginnings

[edit]By March 1938, Glenn was planning to form a new group. The newly reformed band featured several longtime associates of Miller. From his first orchestra, Miller invited back Hal McIntyre, and hired Paul Tanner, Wilbur Schwartz, Ray Eberle (who was the younger brother of Jimmy Dorsey's vocalist Bob Eberly), and his old friend Chummy MacGregor. Miller's perseverance, business expertise, combined with a penchant for showmanship and musical taste, provided the faith for financiers Mike Nidorf and Cy Shribman. Miller used the 'clarinet-lead' sound as the foundation for his new band, and this caught the attention of students at Northeastern campuses. They opened on April 16, 1938, at Raymor Ballroom in Boston. When the band reached New York, they were billed below Freddie Fisher and His Schnickelfritzers, a dance band comedy routine.[3] From Vincent Lopez's group came Marion Hutton, who added enthusiasm and energy in her performances. On September 7, 1938, the band made their first recordings, "My Reverie", "King Porter Stomp" and "By the Waters of Minnetonka", in two parts.[4] Keeping up radio dates, Miller was only booked for one more session the rest of the year.[5]

Glen Island Casino and Meadowbrook Ballroom appearances

[edit]In March 1939, the Glenn Miller Orchestra was given its big break, when they were chosen to play the summer season at the prestigious Glen Island Casino located on the north shore of Long Island Sound in New Rochelle, New York. Frank Dailey, manager of The Meadowbrook Ballroom in Cedar Grove, New Jersey, immediately booked the band for a four-week stay in March and April, before Glen Island. The band was well-received and within days Dailey picked up a three-week extension offer. During this time, Bluebird recording dates became more common, and Glenn added drummer Maurice Purtill and trumpeter Dale "Mickey" McMickle to stabilize personnel. Opening at Glen Island on May 17, 1939, the casino's radio broadcast antenna ensured the Miller band was heard around the country. By late August, the end of their summer season, they had nationwide attention.[6][7][8]

George T. Simon, music writer and one-time drummer for Miller, spoke of the Glen Island broadcasts:

Glen Island was the prestige place for people who listened to bands on radio. The band's first semi hit, "Little Brown Jug", came out just when it opened at Glen Island. That helped. And the clarinet lead in Glenn's arrangements was such a romantic sound! It caught the public fancy during this exposure. Miller began ending his broadcasts from Glen Island with his "Something Old, Something New" medleys. But the most important thing for Glenn's success was that he recorded "In the Mood" while he was at the casino. That made him the Michael Jackson of his day.[6]

Nationwide popularity

[edit]Capitalizing on newfound popularity, Miller decided to add a trombone and a trumpet, giving the band a fuller sound. On April 4, 1939, Miller and his orchestra recorded "Moonlight Serenade". Considered one of the top songs of the swing era, and Miller's best composition, it soon became the theme song to start and end all of his radio performances.

Miller's most popular track "In the Mood" was recorded August 1, 1939. Famous for its opening and bass riffs as well as its "dueling" saxophone solos between Tex Beneke and Al Klink, the song hit number one on the Billboard charts, staying for a total of 30 weeks.[9][10] Joe Garland compiled the song from riffs he'd heard in other songs, and is credited on the label. Elements of "In the Mood" can be found in earlier jazz recordings, such as Jimmy O'Bryant's "Clarinet Getaway", Wingy Manone's "Tar Paper Stomp", and Fletcher Henderson's "Hot and Anxious."[11] Garland put these pieces together and initially offered the song, in a six-minute form, to Artie Shaw. Despite playing it for radio broadcast, Shaw found no success with it in this form. Miller purchased the song in June 1939[12] and asked Eddie Durham to arrange it for his orchestra, and Miller made final tweaks in Victor studios. In a 2000 interview for npr, trombonist Paul Tanner remembered recording the song and playing it live:

He would say, "You fellas do this, and you fellas do that, and let's hear it once." And then, "We're gonna cut from this spot to this spot in the arrangement, and in here we're gonna put a trumpet solo. And in this spot and this spot we're gonna cut way down here and we're gonna have the two saxophones have a little battle in there," and decided to make cuts. And then at the end, Alice [Winkler, the interviewer], if you know the arrangement, at the end there are all those false endings that go on, and it kept getting softer and softer until Glenn would give the drummer a cue and he would hit the cowbell and then we would know that the next time we were to come on very loud. And the dancers just loved it. He tried it out on the dances at the Glen Island Casino, and they loved it. They couldn't figure out how we knew when to come in loud. But, you know, I told them, "Well, we have a sixth sense of that sort of thing." But actually, what happened is the drummer hit the cowbell, and we knew the next time was loud. And this was all Glenn's doing.[13]

On February 5, 1940, Miller recorded "Tuxedo Junction", which hit number one and reportedly sold 115,000 copies within the first week of release, and placed 7th overall for the National Hit Parade that year. Bob Eberly said that it "sold 90,000 copies in the first week, at a time when 25,000 was considered a great seller".[14] In April, the band chant track "Pennsylvania 6-5000", referencing the phone number for the Hotel Pennsylvania, which housed the Café Rouge, a common engagement and broadcasting spot for the band, was released and it too became an instant swing standard.

On January 1, 1941, following tensions regarding licensing fees, radio networks banned ASCAP songs from live performance. Miller had to work to reform his radio programs for BMI published tunes, temporarily switching his theme to "Slumber Song". In early 1941, Marion Hutton left the band to go on maternity leave. In the meantime, Miller needed an additional female vocalist, and he offered Dorothy Claire, then with Bobby Byrne's band, twice her salary. Claire went to work for Miller, despite her signature on a three-year contract with Byrne in November 1940, and Miller ignored Byrne's wishes for compensation. Byrne then launched a $25,000 lawsuit against the Miller orchestra's business dealings.[1] Miller met with Byrne in Columbus, Ohio sometime in early March and settled the dispute – Claire went back to working with Byrne's band. Miller soon hired The Modernaires from Paul Whiteman, who was disbanding his orchestra. Still in need of a female vocalist, the wife of Modernaire Hal Dickinson, Paula Kelly, who had sung previously with Al Donahue, stepped up to fill in the role. The signing of the Modernaires significantly benefitted the Miller organization. Hip and popular with young listeners, the Modernaires' vocal range added a new dimension to Miller's recordings.[15]

In late March, Miller and his orchestra began work on their first motion picture, Sun Valley Serenade. Previously, swing films such as Hollywood Hotel with Benny Goodman's orchestra had only featured bands for song performances; Miller reportedly insisted, perhaps even to the extent of contract clauses, that the plot of Sun Valley revolve around the band rather than only feature them.[15] Harry Warren and Mack Gordon were commissioned to write songs for the film. The Miller band filmed and recorded an extended song-and-dance number featuring the Nicholas Brothers for what was soon to be its biggest selling record, surprise hit "Chattanooga Choo Choo". Despite criticism of the plot,[16] Sun Valley Serenade was received with general positivity from critics, and Miller earned praise for his band's role in the film, with Barry Ulanov writing for Metronome:

Miller comes across as a convincing band leader, and, even more important, a convincing human being in this film. He’s on mostly for music, but most of the film is music and the dozen or so reels are a better showcase for the Glenn Miller band than they are for the Sonja Henie torso and limbs, with and without skates. Never has a movie made more of a popular band and never has a movie featuring such an organization presented its music so tastefully... Pictorially, Trigger Alpert and Maurice Purtill take the honors. Trigger hops around like mad and Maurice looks like the movies’ idea of a swing drummer, all right. They stay within the bounds of good taste, however ... the story is believable, and happily centers around the band, so that the whole thing is a triumph for Glenn Miller and the band.[1]

First gold record presentation

[edit]

In October, ASCAP and the radio networks agreed on a new rate, and the band could finally play "Chattanooga Choo Choo" and their other songs on radio. On February 10, 1942, the manager of record sales for RCA Victor and Bluebird records, W. Wallace Early presented the first gold record ever made to Glenn Miller for “Chattanooga Choo Choo.”[1][17]

Wallace Early: It's a pleasure to be here tonight. And speaking of RCA Victor, we're mighty proud of that "Chattanooga Choo Choo", and the man that made the record, Glenn Miller. You see it's been a long time – 15 years in fact – since any record has sold a million copies. And "Chattanooga Choo Choo" certainly put on steam and breezed right through that million mark by over 200,000 pressings. And we decided that Glenn should get a trophy. The best one we could think of is a gold record of "Chattanooga". And now Glenn, it's yours – with the best wishes of RCA Victor Bluebird Records.

Glenn Miller: Thank you, Wally, that’s really a wonderful present.

Radio announcer, Paul Douglas: I think everyone listening in on the radio should know Glenn, it’s actually a recording of "Chattanooga Choo Choo" but it’s in gold. Solid gold, and it’s really fine.

Glenn Miller: That’s right, Paul, and now for the boys in the band, thanks a million, two hundred thousand.

In early 1942, the band was upgraded from Bluebird to full-price Victor Records. Following very closely in the footsteps of its predecessor, the Miller band started work on their second film, Orchestra Wives in March. Once again, Gordon and Warren were recalled to compose the songs. The previous year, both had composed "At Last" but couldn't place it into Sun Valley Serenade vocally, although it appears in the film in three different instrumental versions. The song was arranged by Jerry Gray in a vocal version, and it was displayed prominently in Orchestra Wives. It became a standard when recorded by Glenn Miller orchestra alumnus Ray Anthony in 1951 in a version that reached no. 2 on the Billboard pop singles chart. Etta James released a popular version in 1961 that added to the iconic status of the song. Akin to "Chattanooga", "(I've Got a Gal In) Kalamazoo" was filmed as a song and dance number featuring the Nicholas Brothers and also sold a million pressings, with Billboard ranking it among the most popular records of the year.

AFM ban and disbandment

[edit]In mid–July, Miller and the band recorded thirteen sides, as James Petrillo, chief of the musicians' union, embarked on a 28-month recording ban. The strike prevented Miller from making additional records in his career, although Victor slowly released the last set of tracks, with "That Old Black Magic" hitting number one in May 1943, over eight months after his the orchestra disbanded.

Miller began incorporating more patriotic themes into his radio shows and recordings after the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor.[1]

At the top of his civilian musical career in 1942, Glenn Miller decided to join the troops he had been entertaining. As a 38-year-old, he was too old to be drafted. First, he tried to join the United States Navy, but officials told him they "could not use his services" at that time. Miller then wrote to Army Brigadier General Charles Young. He successfully persuaded the United States Army to accept him, so he could, "be placed in charge of a modernized Army band." He reported for duty on October 7, 1942. He soon transferred to the United States Army Air Forces where he formed what would become the Major Glenn Miller Army Air Forces Orchestra, the precursor of the US Air Force Airmen of Note.[1]

Glenn Miller and his Orchestra broadcast their final Chesterfield radio spot on CBS radio on September 24, 1942. During the program, Miller announced that from then on, the Chesterfield radio broadcast would be done by Harry James. Harry James played "Jukebox Saturday Night" with the band that night. They played their last concert on September 27, 1942, in Passaic, New Jersey.[1]

Radio success

[edit]Radio played a pivotal role in the success of Glenn Miller and His Orchestra. Featured heavily on the format during their existence, many of their earlier programs from such venues as the Paradise Restaurant, Glen Island and the Meadowbrook Ballroom used remote connections to the National Broadcasting Company, on both NBC–Red and NBC–Blue.[18]

The makers of Chesterfield Cigarettes hosted a half-hour radio show on CBS that featured King of Jazz Paul Whiteman. Whiteman decided to retire and recommended Glenn as a replacement. On December 27, 1939, Miller took over the program as Chesterfield Moonlight Serenade. During the first 13 weeks, The Andrews Sisters were featured as Chesterfield were worried over whether Miller could sustain his popularity. Their fear subsided, and the program, reformatted for 15 minutes, aired Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday nights at 10:15 pm. Miller and his band held the slot until their disbandment in 1942.[18]

In 1940, the band broadcast from the first time from the Café Rouge at the Hotel Pennsylvania, soon to become a regular booking and a host of long-term engagements. By then, the Miller band had several NBC sustaining broadcasts in addition to three CBS programs, reaching American homes 6–7 days a week. In August, Miller's orchestra had an hour-long program on NBC–Blue, Glenn Miller's Sunset Serenade featuring prizes Miller paid for out-of-pocket. A review in Billboard commented, "Unusual length of the program allows Miller to display all the top items in his library."[19]

Chart success

[edit]According to Paul Albone, of the 121 singles by Glenn Miller and His Orchestra that made the charts, 69 were Top Ten hits, and 16 reached number-one.[20][21] In just a 4-year career, Miller and His Orchestra's songs spent a cumulative total of 664 weeks, nearly thirteen years, on the charts, 79 of which were at the number-one position.[20][21] Miller also has the distinction of three posthumous albums reaching number-one on Billboard charts: Glenn Miller in 1945, its follow-up in 1947, and his original recordings repackaged for the release of The Glenn Miller Story in 1954.[21]

Past members

[edit]

Discography

[edit]Singles

[edit]Million-selling singles:[22]

- 1939: "Little Brown Jug"

- 1939: "Moonlight Serenade"

- 1939: "In the Mood"

- 1940: "Tuxedo Junction"

- 1940: "Pennsylvania 6-5000"

- 1941: "Chattanooga Choo Choo"

- 1941: "A String of Pearls"

- 1941: "Moonlight Cocktail"

- 1942: "American Patrol"

- 1942: "(I've Got a Gal In) Kalamazoo"

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i "A Portrait of Glenn Miller" (PDF). www.colorado.edu. Glenn Miller Archive. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-10-16. Retrieved 2018-10-16.

- ^ Gilliland, John (1994). Pop Chronicles the 40s: The Lively Story of Pop Music in the 40s (audiobook). ISBN 978-1-55935-147-8. OCLC 31611854. Tape 2, side A.

- ^ "Captain Swing - Glenn Miller - America in WWII magazine". www.americainwwii.com. Archived from the original on 2015-09-21. Retrieved 2015-08-07.

- ^ "A Bluebird Reverie – The First RCA Session". 1 April 2014. Archived from the original on 31 August 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ Settlemier, Tyrone. "The Online 78 rpm Discographical Project". www.78discography.com. Archived from the original on 2017-05-05. Retrieved 2015-03-06.

- ^ a b "POP/JAZZ; GLENN MILLER SOUND OF 1939 AT GLEN ISLAND CASINO". The New York Times. 27 April 1984. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ^ "Glenn Miller Orchestra – History". glennmillerorchestra.com. Archived from the original on 2015-02-22. Retrieved 2015-03-06.

- ^ http://ww Archived 2013-07-12 at the Wayback Machine w.glennmiller.com/index.php

- ^ "Army Band Hits High Note With Community". Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-07-28.

- ^ Tsort. "Song title 150 - In the Mood". tsort.info. Archived from the original on 2015-07-17. Retrieved 2015-07-28.

- ^ ""In the Mood"—Glenn Miller (1939)" (PDF). Library of Congress. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-10-16. Retrieved 2018-10-16.

- ^ Spragg, Dennis. "In the Mood" (PDF). www.colorado.edu. Glenn Miller Archive. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-06-19. Retrieved 2018-10-16.

- ^ "In the Mood". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 2018-07-11. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- ^ Simon, George T. Glenn Miller and His Orchestra. NY: Crowell, 1974.

- ^ a b Spragg, Dennis. "Sun Valley Serenade 75th Anniversary Commemoration" (PDF). Glenn Miller Archive. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-10-16. Retrieved 2018-10-16.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (6 September 1941). "Sonia Henie in 'Sun Valley Serenade,' a Sparkling and Melodious Outdoor Picture, at the Roxy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ Murrells, Joseph (1978). The Book of Golden Discs (2nd ed.). London: Barrie and Jenkins Ltd. p. 4. ISBN 0-214-20512-6.

- ^ a b "Radio Recordings" (PDF). colorado.edu. Glenn Miller Archive. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-09-05. Retrieved 2018-10-16.

- ^ Carter, Dick (January 3, 1942). "On the Air: Glenn Miller". Billboard. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ a b Whitburn, Joel. Pop Memories (1900-1940). Record Research.

- ^ a b c Whitburn, Joel (2015). Pop Hits Singles and Albums, 1940-1954. Record Research. ISBN 978-0-89820-198-7.

- ^ Popa, Christopher. "Record Sales". Big Band Library. Archived from the original on 2018-07-18. Retrieved 2018-10-16.

External links

[edit]- Website of past vocalist Eileen Burns Archived 2013-05-28 at the Wayback Machine

- YouTube Videos from 1983 GMO US and Japan Tour Archived 2016-04-29 at the Wayback Machine