Kraken

The kraken (/ˈkrɑːkən/)[6] is a legendary sea monster of enormous size, per its etymology something akin to a cephalopod, said to appear in the sea between Norway and Iceland. It is believed that the legend of the Kraken may have originated from sightings of giant squid, which may grow to 12–15 m (40–50 feet) in length.

The kraken, as a subject of sailors' superstitions and mythos, was first described in the modern era in a travelogue by Francesco Negri in 1700. This description was followed in 1734 by an account from Dano-Norwegian missionary and explorer Hans Egede, who described the kraken in detail and equated it with the hafgufa of medieval lore. However, the first description of the creature is usually credited to the Danish bishop Pontoppidan (1753). Pontoppidan was the first to describe the kraken as an octopus (polypus) of tremendous size,[b] and wrote that it had a reputation for pulling down ships. The French malacologist Denys-Montfort, of the 19th century, is also known for his pioneering inquiries into the existence of gigantic octopuses (Octupi).

The great man-killing octopus entered French fiction when novelist Victor Hugo (1866) introduced the pieuvre octopus of Guernsey lore, which he identified with the kraken of legend. This led to Jules Verne's depiction of the kraken, although Verne did not distinguish between squid and octopus.

Linnaeus may have indirectly written about the kraken. Linnaeus wrote about the Microcosmus genus (an animal with various other organisms or growths attached to it, comprising a colony). Subsequent authors have referred to Linnaeus's writing, and the writings of Bartholin's cetus called hafgufa, and Paullini's monstrum marinum as "krakens".[c] That said, the claim that Linnaeus used the word "kraken" in the margin of a later edition of Systema Naturae has not been confirmed.

Etymology

[edit]The English word "kraken" (in the sense of sea monster) derives from Norwegian kraken or krakjen, which are the definite forms of krake ("the krake").[6]

According to a Norwegian dictionary, the root meaning of krake is "malformed or overgrown, crooked tree".[7] It originates from Old Norse kraki, which is etymologically related to Old Norse krókr, lit. 'hook', cognate with "crook". This is backed up by the Swedish dictionary SAOB, published by the Swedish Academy, which gives essentially the exact same description for the word in Swedish and confirming the lead krak as a diminutive form of krok, Norwegian and Swedish for 'hook/crook' (krake thus roughly translate to "crookie").[8] With time, "krake" have come to mean any severed tree stem or trunk with crooked outgrowths, in turn giving name to objects and tools based on such, notably for the subject matter, primitive anchors and drags (grapnel anchors) made from severed spruce tops or branchy bush trunks outfitted with a stone sinker,[7][8] known as krake, but also krabbe in Norwegian or krabba in Swedish (lit. 'crab').[d] Old Norse kraki mostly corresponds to these uses in modern Icelandic, meaning, among other things, "twig" and "drag", but also "pole/stake used in pole blockages" and "boat hook".[12] Swedish SAOB gives the translations of Icelandic kraki as "thin rod with hook on it", "wooden drag with stone sinker" and "dry spruce trunk with the crooked, stripped branches still attached".[8]

Kraken is assumed to have been named figuratively after the meaning “crooked tree” or its derivate meaning “drag”, as trunks with crooked branches or outgrowths, and especially drags, wooden or not, readily conjure up the image of a cephalopod or similar.[13][14][8][7] This idea seems to first have been notably remarked by Icelandic philologist Finnur Jónsson in 1920.[15] A synonym for kraken has also been krabbe (see below), which further indicates a name-theme referencing drags.

Synonyms

[edit]Besides kraken, the monster went under a variety of names early on, the most common after kraken being horven ("the horv").[16] Icelandic philologist Finnur Jónsson explained this name in 1920 as an alternative form of harv (lit. 'harrow') and conjectured that this name was suggested by the inkfish's action of seeming to plow the sea.[15]

Some of the synonyms of krake given by Erik Pontoppidan were, in Danish:[e]

- horv (horven) – harrow[15][17][16]

- søe-horv (søe-horven) – sea-harrow[15][18]

- søe-krake (søe-kraken) – sea-krake[17]

- kraxe (kraxen) – alternate spelling of "krakse"[17][f]

- krabbe (krabben) – named after the drag (grapnel anchor) "crab" (see above)[18][7][8]

- anker-trold – anchor-troll[18][g]

Related words

[edit]Since the 19th century, the word krake have, beyond the monster, given name to the cephalopod order Octopoda in Swedish (krakar)[h] and German (Kraken), resulting in many species of octopuses partly named such, such as the common octopus (Octopus vulgaris), which is named jättekrake ("giant kraken") in Swedish and Gewöhnlicher Krake ("common kraken") in German.[citation needed] The family Octopodidae is also known as Echte Kraken ("true krakens") in German. In Icelandic, octopoda is instead named kolkrabbar ("coal crabs") after the crab nickname, the common octopus simply named kolkrabbi.[citation needed]

The Swedish diminutive form kräkel, a word for a branchy/spiny piece of wood,[28] have given name to a variety of sea dwelling plants in Swedish, most notably furcellaria lumbricalis, a species of red algae.[29][i] There is also the morphological derivation kräkla (dialectal Norwegian: krekle), meaning crooked piece of wood, which has given name to primitive forms of whisks and beaters (cooking), made from the tops of trees by keeping a row of twigs as the beating element, resembling the appearance of a cephalopod, but also crosiers and shepherd's crooks.[32]

Shetlandic krekin for "whale", a taboo word, is listed as etymologically related.[13][33]

General description and myth

[edit]In Norwegian sailor folklore, kraken ("the krake" or "the crookie"), also known as horven (among others), is a legendary sea monster said to appear in the sea between Norway and Iceland.[citation needed]

It is said that when fishermen row out a few miles (Scandinavian miles) from the coast on a hot summer's day in a calm, and according to normal calculations should find a depth of 80–100 fathoms (140–180 metres (460–590 ft) deep), it sometimes happens that the plummet bottoms at 20–30 fathoms (35–50 metres (115–164 ft) deep). But in this water stand the most abundant shoals of cod and lings. Then you can assume that the kraken lurks down there; as it is he who forms the artificial elevation of the bottom and by his secretions attracts fish there. But if those fishing notice that the kraken is rising, it is necessary to row away for all the boat can take. After a few minutes, the beast can then be seen lifting the upper part of its body above the surface of the water, which for a quarter of a mile (ca 1.5 mi.) in circumference appears as a collection of skerries, covered with swaying, seaweed-like growths. Finally, a few shining tentacles rise up in the air, increasingly thicker at the bottom, which can even appear as high as ship's masts. After a while, the kraken gives in to sinking again, bringing the ship down with it, and you then have to be careful not to run into the suction vortex that is formed.[16]

First descriptions

[edit]

The first description of the krake as "sciu-crak" was given by Italian writer Negri in Viaggio settentrionale (Padua, 1700), a travelogue about Scandinavia.[39][40] The book describes the sciu-crak as a massive "fish" which was many-horned or many-armed. The author also distinguished this from a sea-serpent.[41] One such serpent is that of Jörmungandr (also known as the Migard Serpent or World Serpent), an iconic beast in Norse mythology who acts as Thor's antagonist, and will ultimately defeat him via poison during Ragnarok. As it is stated in the ancient Prose Eddas, “The Midgard Serpent shall blow venom so that he shall sprinkle all the air and water; and he is very terrible…”[42]

The kraken was described as a many-headed and clawed creature by Egede (1741)[1729], who stated it was equivalent to the Icelanders' hafgufa,[43] but the latter is commonly treated as a fabulous whale.[44] Erik Pontoppidan (1753), who popularized the kraken to the world, noted that it was multiple-armed according to lore, and conjectured it to be a giant sea-crab, starfish or a polypus (octopus).[45] Still, the bishop is considered to have been instrumental in sparking interest for the kraken in the English-speaking world,[46] as well as becoming regarded as the authority on sea-serpents and krakens.[47]

Although it has been stated that the kraken (Norwegian: krake) was "described for the first time by that name" in the writings of Erik Pontoppidan, bishop of Bergen, in his Det første Forsøg paa Norges naturlige Historie "The First Attempt at [a] Natural History of Norway" (1752–53),[48] a German source qualified Pontoppidan to be the first source on kraken available to be read in the German language.[49] A description of the kraken had been anticipated by Hans Egede.[50]

Denys-Montfort (1801) published on two giants, the "colossal octopus" with the enduring image of it attacking a ship, and the "kraken octopod", deemed to be the largest organism in zoology. Denys-Montfort matched his "colossal" with Pliny's tale of the giant polypus that attacked ships-wrecked people, while making correspondence between his kraken and Pliny's monster called the arbor marina.[k] Finnur Jónsson (1920) also favored identifying the kraken as an inkfish (squid/octopus) on etymological grounds.[citation needed]

Egede

[edit]The krake (English: kraken) was described by Hans Egede in his Det gamle Grønlands nye perlustration (1729; Ger. t. 1730; tr. Description of Greenland, 1745),[51] drawing from the fables of his native region, the Nordlandene len of Norway, then under Danish rule.[53][54]

According to his Norwegian informants, the kraken's body measured many miles in length, and when it surfaced it seemed to cover the whole sea, further described as "having many heads and a number of claws". With its claws it captured its prey, which included ships, men, fish, and animals, carrying its victims back into the depths.[54] Egede conjectured that the krake was equatable to the monster that the Icelanders call hafgufa, but as he had not obtained anything related to him through an informant, he had difficulty describing the latter.[43][l]

According to the lore of Norwegian fishermen, they could mount upon the fish-attracting kraken as if it were a sand-bank (Fiske-Grund 'fishing shoal'), but if they ever had the misfortune to capture the kraken, getting it entangled on their hooks, the only way to avoid destruction was to pronounce its name to make it go back to its depths.[56][57] Egede also wrote that the krake fell under the general category of "sea spectre" (Danish: søe-trold og [søe]-spøgelse),[59] adding that "the Draw" (Danish: Drauen, definite form) was another being within that sea spectre classification.[23][57][m][citation needed]

Hafgufa

[edit]Egede also made the aforementioned identification of krake as being the same as the hafgufa of the Icelanders,[19][43] though he seemed to have obtained the information indirectly from the medieval Norwegian treatise, the Speculum Regale (or King's Mirror, c. 1250).[n][62][63][50][19]

Later, David Crantz in Historie von Grönland (History of Greenland, 1765) also reported kraken and the hafgufa to be synonymous.[64][65]

An English translator of the King's Mirror in 1917 opted to translate hafgufa as kraken.[66]

The hafgufa (described as the largest of the sea monsters, inhabiting the Greenland Sea) from the King's Mirror[67][68][o] continues to be identified with the kraken in some scholarly writings,[70][19] and if this equivalence were allowed, the kraken-hafgufa's range would extend, at least legendarily, to waters approaching Helluland (Baffin Island, Canada), as described in Örvar-Odds saga.[71][p]

The anonymously written Historia Norwegiæ also states that the hafgufa inhabited a deep fjord, accompanied by other sea beasts such as the ‘hafstramb’ , a gigantic creature with no head nor tail, the ‘hrosshvalr’, depicted as a hippocampus (half horse, half fish) in imagery, as well as recognizable monstrosities like the Charybdis and Scylla.[72]

Contrary opinion

[edit]The description of the hafgufa in the King's Mirror suggests a garbled eyewitness account of what was actually a whale, at least according to the Grönlands historiske Mindesmaerker.[73] Halldór Hermannsson also reads the work as describing the hafgufa as a type of whale.[44]

The King's Mirror does somewhat extensively reference maritime animal life, including: twenty-one whale species; six seal varieties; description of the walrus; ‘sea-hedges’; as well as the legendary likes of the merman, mermaid, and kraken. While the whales, specifically within the Icelandic oceans, are explained in fair amounts of detail — such: as those called ‘blubber-cutters’, the most numerous whales, growing to twenty ells in length, and noted as harmless to ships and men; the porpoise, which grows to a maximum of five ells; and the ‘caaing whale’, growing to lengths of seven ells — the tales of other, more dangerous and mythical ‘fish’ leave more room for ambiguity, and thus, interrogation.[74]

Finnur Jónsson (1920) having arrived at the opinion that the kraken probably represented an inkfish (squid/octopus), as discussed earlier, expressed his skepticism towards the persistently accepted notion that the kraken originated from the hafgufa.[15]

Pontoppidan

[edit]Erik Pontoppidan's Det første Forsøg paa Norges naturlige Historie (1752, actually volume 2, 1753)[75] made several claims regarding kraken, including the notion that the creature was sometimes mistaken for a group of small islands with fish swimming in-between,[76] Norwegian fishermen often took the risk of trying to fish over kraken, since the catch was so plentiful[77] (hence the saying "You must have fished on Kraken"[78]).

However, there was also the danger to seamen of being engulfed by the whirlpool when it submerged,[79][11] and this whirlpool was compared to Norway's famed Moskstraumen often known as "the Maelstrom".[80][81]

Pontoppidan also described the destructive potential of the giant beast: "it is said that if [the creature's arms] were to lay hold of the largest man-of-war, they would pull it down to the bottom".[82][79][11][83]

Kraken purportedly exclusively fed for several months, then spent the following few months emptying its excrement, and the thickened clouded water attracted fish.[84] Later Henry Lee commented that the supposed excreta may have been the discharge of ink by a cephalopod.[85]

Taxonomic identifications

[edit]Pontoppidan wrote of a possible specimen of the krake, "perhaps a young and careless one", which washed ashore and died in 1680 near Alstahaug Church on the island of Alsta, Norway.[83][81][21] He observed that it had long "arms", and guessed that it must have been crawling like a snail/slug with the use of these "arms", but got lodged in the landscape during the process.[86][87] 20th-century malacologist Paul Bartsch conjectured this to have been a giant squid,[88] as did literary scholar Finnur Jónsson.[89]

However, what Pontoppidan actually stated regarding what creatures he regarded as candidates for the kraken is quite complicated.[citation needed]

Pontoppidan did tentatively identify the kraken to be a sort of giant crab, stating that the alias krabben best describes its characteristics.[20][90][81][q]

However, further down in his writing, compares the creature to some creature(s) from Pliny, Book IX, Ch. 4: the sea-monster called arbor, with tree-branch like multiple arms,[r] complicated by the fact that Pontoppidan adds another of Pliny's creature called rota with eight arms, and conflates them into one organism.[99][100] Pontoppidan is suggesting this is an ancient example of kraken, as a modern commentator analyzes.[101]

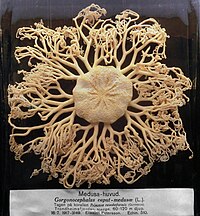

Pontoppidan then declared the kraken to be a type of polypus (=octopus)[104] or "starfish", particularly the kind Gessner called Stella Arborescens, later identifiable as one of the northerly ophiurids[105] or possibly more specifically as one of the Gorgonocephalids or even the genus Gorgonocephalus (though no longer regarded as family/genus under order Ophiurida, but under Phrynophiurida in current taxonomy).[109][112]

This ancient arbor (admixed rota and thus made eight-armed) seems like an octopus at first blush[113] but with additional data, the ophiurid starfish now appears bishop's preferential choice.[114]

The ophiurid starfish seems further fortified when he notes that "starfish" called "Medusa's heads" (caput medusæ; pl. capita medusæ) are considered to be "the young of the great sea-krake" by local lore. Pontoppidan ventured the 'young krakens' may rather be the eggs (ova) of the starfish.[115] Pontopiddan was satisfied that "Medusa's heads" was the same as the foregoing starfish (Stella arborensis of old),[116] but "Medusa's heads" were something found ashore aplenty across Norway according to von Bergen, who thought it absurd these could be young "Kraken" since that would mean the seas would be full of (the adults).[117][118] The "Medusa's heads" appear to be a Gorgonocephalid, with Gorgonocephalus spp. being tentatively suggested.[119][s][121][124]

In the end though, Pontoppidan again appears ambivalent, stating "Polype, or Star-fish [belongs to] the whole genus of Kors-Trold ['cross troll'], ... some that are much larger, .. even the very largest ... of the ocean", and concluding that "this Krake must be of the Polypus kind".[125] By "this Krake" here, he apparently meant in particular the giant polypus octopus of Carteia from Pliny, Book IX, Ch. 30 (though he only used the general nickname "ozaena" 'stinkard' for the octopus kind).[100][126][t]

Denys de Montfort

[edit]In 1802, the French malacologist Pierre Denys de Montfort recognized the existence of two "species" of giant octopuses in Histoire Naturelle Générale et Particulière des Mollusques, an encyclopedic description of mollusks.[2]

The "colossal giant" was supposedly the same as Pliny's "monstrous polypus",[127][128] which was a man-killer which ripped apart (Latin: distrahit) shipwrecked people and divers.[131][132] Montfort accompanied his publication with an engraving representing the giant octopus poised to destroy a three-masted ship.[2][133]

Whereas the "kraken octopus", was the most gigantic animal on the planet in the writer's estimation, dwarfing Pliny's "colossal octopus"/"monstrous polypus",[134][135] and identified here as the aforementioned Pliny's monster, called the arbor marinus.[136]

Montfort also listed additional wondrous fauna as identifiable with the kraken.[137] [138] There was Paullini's monstrum marinum glossed as a sea crab (German: Seekrabbe),[139] which a later biologist has suggested to be one of the Hyas spp.[140] It was also described as resembling Gessner's Cancer heracleoticus crab alleged to appear off the Finnish coast.[139][135] von Bergen's "bellua marina omnium vastissima" (meaning 'vastest-of-all sea-beast'), namely the trolwal ('ogre whale', 'troll whale') of Northern Europe, and the Teufelwal ('devil whale') of the Germans follow in the list.[141][138]

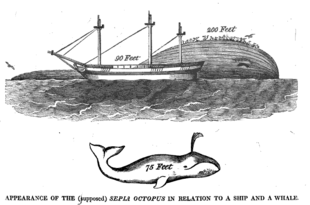

Angola octopus, pictured in St. Malo

[edit]It is in his chapter on the "colossal octopus" that Montfort provides the contemporary eyewitness example of a group of sailors who encounter the giant off the coast of Angola, who afterwards deposited a pictorial commemoration of the event as a votive offering at St. Thomas's chapel in Saint-Malo, France.[142] Based on that picture, Montfort drew a "colossal octopus" attacking a ship, and included the engraving in his book.[143][144] However, an English author recapitulating Montfort's account of it attaches an illustration of it, which was captioned: "The Kraken supposed a sepia or cuttlefish", while attributing Montfort.[145]

Hamilton's book was not alone in recontextualizing Montfort's ship-assaulting colossal octopus as a kraken; for instance, the piece on the "kraken" by American zoologist Packard.[146]

The Frenchman Montfort used the obsolete scientific name Sepia octopodia but called it a poulpe,[147] which means "octopus" to this day; meanwhile the English-speaking naturalists had developed the convention of calling the octopus "eight-armed cuttle-fish", as did Packard[4] and Hamilton,[5] even though modern-day speakers are probably unfamiliar with that name.

Warship Ville de Paris

[edit]

Having accepted as fact that a colossal octopus was capable of dragging a ship down, Montfort made a more daring hypothesis. He attempted to blame colossal octopuses for the loss of ten warships under British control in 1782, including six captured French men-of-war. The disaster began with the distress signal fired by the captured ship of the line Ville de Paris which was then swallowed up by parting waves, and the other ships coming to aid shared the same fate. He proposed, by process of elimination, that such an event could only be accounted for as the work of many octopuses.[148][149][150]

But it has been pointed out the sinkings have simply been explained by the presence of a storm,[133] and there appeared a surviving witness that stated they ran into a hurricane.[1] Montfort's involving octopuses as complicit has been characterized as "reckless falsity".[150]

It has also been noted that Montfort once quipped to a friend, DeFrance: "If my entangled ship is accepted, I will make my 'colossal poulpe' overthrow a whole fleet".[151][152][4]

Niagara

[edit]The ship Niagara on course from Lisbon to New York in 1813 logged a sighting of a marine animal spotted afloat at sea. It was claimed to be 60 m (200 feet) in length, covered in shells, and had many birds alighted upon it.[citation needed]

Samuel Latham Mitchill reported this, and referencing Montfort's kraken, reproduced an illustration of it as an octopus.[153]

Linnaeus's microcosmus

[edit]

The famous Swedish 18th-century naturalist Carl Linnaeus in his Systema Naturae (1735) described a fabulous genus Microcosmus a "body covered with various heterogeneous [other bits]" (Latin: Corpus variis heterogeneis tectum).[140][154][155][u]

Linnaeus cited four sources under Microcosmus, namely:[v][140][157] Thomas Bartholin's cetus (≈whale) type hafgufa;[159] Paullin's monstrum marinum aforementioned;[139] and Francesco Redi's giant tunicate (Ascidia[140]) in Italian and Latin.[160][161]

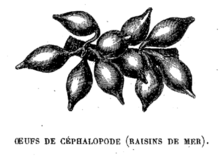

According to the Swedish zoologist Lovén, the common name kraken was added to the 6th edition of Systema Naturae (1748),[140] which was a Latin version augmented with Swedish names[162] (in blackletter), but such Swedish text is wanting on this particular entry, e.g. in the copy held by NCSU.[156] It is true that the 7th edition of 1748, which adds German vernacular names,[162] identifies the Microcosmus as "sea-grape" (German: Meertrauben), referring to a cluster of cephalopod eggs.[163][164][w][x]

Also, the Frenchman Louis Figuier in 1860 misstated that Linnaeus included in his classification a cephalopod called "Sepia microcosmus"[y] in his first edition of Systema Naturae (1735).[168] Figuier's mistake has been pointed out, and Linnaeus never represented the kraken as such a cephalopod.[169] Nevertheless, the error has been perpetuated by even modern-day writers.[171]

Linnaeus in English

[edit]Thomas Pennant, an Englishman, had written of Sepia octopodia as "eight-armed cuttlefish" (we call it octopus today), and documented reported cases in the Indian isles where specimen grow to 2 fathoms [3.7 m; 12 ft] wide, "and each arms 9 fathoms [16 m; 54 ft] long".[4][3] This was added as a species Sepia octopusa [sic.] by William Turton in his English version of Linnaeus's System of Nature, together with the account of the 9-fathom-long (16 m; 54 ft) armed octopuses.[4][172]

The trail stemming from Linnaeus, eventually leading to such pieces on the kraken written in English by the naturalist James Wilson for the Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine in 1818 sparked an awareness of the kraken among 19th-century English, hence Tennyson's poem, "The Kraken".[70]

Iconography

[edit]

As to the iconography, Denys-Montfort's engraving of the "colossal octopus" is often shown, though this differs from the kraken according to the French malacologist,[143] and commentators are found characterizing the ship attack representing the "kraken octopod".[4][174]

And after Denys-Monfort's illustration, various publishers produced similar illustrations depicting the kraken attacking a ship.[5][173]

Whereas the kraken was described by Egede as having "many Heads and a Number of Claws", the creature is also depicted to have spikes or horns, at least in illustrations of creatures which commentators have conjectured to be krakens. The "bearded whale" shown on an early map (pictured above) is conjectured to be a kraken perhaps (cf. §Olaus Magnus below). Also, there was an alleged two-headed and horned monster that beached ashore in Dingle, County Kerry, Ireland, thought to be a giant cephalopod, of which there was a picture/painting made by the discoverer.[175] He made a travelling show of his work on canvas, as introduced in a book on the kraken.[176]

Olaus Magnus

[edit]Olaus gives description of a whale with two elongated teeth ("like a boar's or elephant's tusk") to protect its huge eyes, which "sprouts horns", and although these are as hard as horn, they can be made supple also.[177][38] But the tusked form was named "swine-whale" (German: Schweinwal), and the horned form "bearded whale" (German: Bart-wal) by Swiss naturalist Gessner, who observed it possessed a "starry beard" around the upper and lower jaws.[178][35] At least one or two writers have suggested this might represent the kraken of Norwegian lore.[36][37]

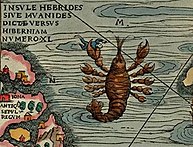

While Swedish writer Olaus Magnus did not use the term kraken, various sea-monsters were illustrated on his famous map, the Carta marina (1539). Modern writers have since tried to interpret various sea creatures illustrated as a portrayal of the kraken.[citation needed]

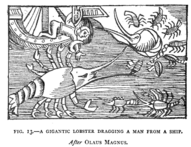

Ashton's Curious Creatures (1890) drew significantly from Olaus's work[184] and even quoted the Swede's description of the horned whale.[185] But he identified the kraken as a cephalopod and devoted much space on Pliny's and Olaus's descriptions of the giant "polypus",[186] noting that Olaus had represented the kraken-polypus as a crayfish or lobster in his illustrations,[187] and even reproducing the images from both Olaus's book[188][177][38][z] and his map.[189][190] In Olaus book, the giant lobster illustration is uncaptioned, but appears right above the words "De Polypis (on the octopus)", which is the chapter heading.[177] Hery Lee was also of the opinion that the multi-legged lobster was a misrepresentation of a reported cephalopod attack on a ship.[191]

The legend in Olaus's map fails to clarify on the lobster-like monster "M",[aa] depicted off the island of Iona.[ab][193] However, the associated writing called the Auslegung adds that this section of the map extends from Ireland to the "Insula Fortunata".[194] This "Fortunate Island" was a destination on St. Brendan's Voyage, one of whose adventures was the landing of the crew on an island-sized monstrous fish,[ac] as depicted in a 17th-century engraving (cf. figure right);[196] and this monstrous fish, according to Bartholin was the aforementioned hafgufa,[159] which has already been discussed above as one of the creatures of lore equated with kraken.[citation needed]

Giant squid

[edit]

The piece of squid recovered by the French ship Alecton in 1861, discussed by Henry Lee in his chapter on the "Kraken",[197] would later be identified as a giant squid, Architeuthis by A. E. Verrill.[198]

After a specimen of the giant squid, Architeuthis, was discovered by Rev. Moses Harvey and published in science by Professor A. E. Verrill, commentators have remarked on this cephalopod as possibly explaining the legendary kraken.[199][200][201]

A similar discovery was made in 1873 by Theophilus Piccot and his assistant while fishing for herring in Newfoundland’s Conception Bay. As they fished, they saw some large mass floating before them, and upon further investigation, they discovered that the creature had a beak the size of a “six gallon keg”, tentacles greater in height than the two men, and the ability to spew ink when threatened. Although this beast was able to escape the two men, Piccot did manage to hack two of the creature's tentacles off with a hatchet he had on board. After bringing the biological evidence to light, it was later concluded that squids of the giant variety do exist in our seas. Moreover, it was uncovered that these squid were not only larger than whales, but preyed upon them.[202]

Historian Otto Latva, who has studied the historical relationship between humans and giant squid, has pointed out that giant squid did not become widely associated with the myth of the kraken in Western culture until the late 19th century. In his book The Giant Squid in Transatlantic Culture, he suggests that the kraken may not even have originated from an animal sighting. Influenced by Enlightenment ideals and the Linnean classification system, however, natural historians and others interested in the study of nature began to look for an explanation for it among marine animals in the 18th century. Among other species, starfish, whales, crustaceans and shelled marine molluscs were suggested as models for the kraken. It was not until Pierre Denys de Montfort's research on molluscs in the early 19th century that the octopus became established in Western culture as an archetype for the kraken. As the kraken became understood as a giant octopus, it was also easy to start interpreting the large squid as the model for kraken stories. However, it was not until the late 19th century that such interpretations became widespread. As Latva points out, the giant squid is not the archetype of the mythical kraken, but was made into one just over 100 years ago in the late 19th century.[203][dubious – discuss]

Paleo-cephalopod

[edit]Paleontologist Mark McMenamin and his spouse Dianna Schulte McMenamin claimed that an ancient, giant cephalopod resembling the legendary kraken caused the deaths of ichthyosaurs during the Triassic Period.[204][205][206][207] However, this theory has been met with criticisms by multiple researchers.[208][209][210][211]

Literary influences

[edit]

The French novelist Victor Hugo's Les Travailleurs de la mer (1866, "Toilers of the Sea") discusses the man-eating octopus, the kraken of legend, called pieuvre by the locals of the Channel Islands (in the Guernsey dialect, etc.).[212][213][ad] Hugo's octopus later influenced Jules Verne's depiction of the kraken in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas,[215] though Verne also drew on the real-life encounter the French ship Alecton had with what was probably a giant squid.[216] It has been noted that Verne indiscriminately interchanged kraken with calmar (squid) and poulpe (octopus).[217]

In the English-speaking world, examples in fine literature are Alfred Tennyson's 1830 irregular sonnet The Kraken,[218] references in Herman Melville's 1851 novel Moby-Dick (Chapter 59 "Squid"),[219]

Modern use

[edit]Although fictional and the subject of myth, the legend of the Kraken continues to the present day, with numerous references in film, literature, television, and other popular culture topics.[220]

Examples include: John Wyndham's novel The Kraken Wakes (1953), the Kraken of Marvel Comics, the 1981 film Clash of the Titans and its 2010 remake of the same name, and the Seattle Kraken professional ice hockey team. Krakens also appear in video games such as Sea of Thieves, God of War II, Return of the Obra Dinn and Dredge.[citation needed] The kraken was also featured in two of the Pirates of the Caribbean movies, as the pet of the fearsome Davy Jones in the 2006 film, Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest and appears in the film's sequel, At World's End.[citation needed] In George R.R. Martin's fantasy novel series, A Song of Ice and Fire and its HBO series adaptations, Game of Thrones and House of the Dragon, the mythical kraken is the sigil of House Greyjoy of the Iron Islands. [citation needed]

The character of Cthulhu, created by H.P. Lovecraft in 1928, also serves as a modern depiction of the kraken, as this giant, squid-like humanoid creature embodies the horror originating with the idea of the mythological serpent, often denoting apocalypse, death, or sin, as well as the more contemporary concept of bodily horror.[221]

Two features on the surfaces of other celestial objects have been named after the Kraken. Kraken Mare, a major sea of liquid ethane and methane, is the largest known body of liquid on Saturn's moon Titan.[222] Kraken Catena is a crater chain and possible tectonic fault on Neptune's moon Triton.[223]

See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Caption: "The Kraken, supposed a sepia or cuttlefish from Denys Montford" [sic.]". Sepia was formerly the genus that octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish (cephalopods) were all assigned to. Thus "eight-armed cuttle-fish" became the standardized name for "octopus".[3][4]

- ^ He vacillated between polypus and "star fish" however.

- ^ Denys-Montfort's footnote identified his kraken with Paullini's monstrum marinum also, leading Samuel Latham Mitchill to comment that "Linnaeus considered the Kraken as a real existence", publishing it under Microcosmus.

- ^ Norwegian: Krabbe, Swedish: krabba (lit. 'crab') as a word for drag (grapnel anchor) is assumed to be figuratively derived from the animal of the same name, as both shares the nature of crawling on the sea bed. The word stems from Old Norse: krabbi, etymologically root cognate with Middle Low German: krabbe, Old English: crabba, 'to crawl'.[9][10][11]

- ^ Pontoppidan of course wrote in Danish, the standard literary language for Norwegians at the time, though words like krake were presumably taken down from the mouths of the native Norwegian populace.

- ^ With definite article suffixed forms such as Kraxen or Krabben[19] appearing in the English translation.[20]

- ^ Pontopoppidan's "Soe-draulen, Soe-trolden, Sea-mischief" has been frequently requoted,[21][22] but these terms can be deferred to Egede's explanation (discussed further, below) that employs søe-trold as a general classification, under which krake and the søe-drau fall.[23] The word drau as a variant of draug was recognized by Pontoppidan as meaning 'spøgelse ghost, spectre',[24] and the latter form draug is defined more specifically as a being associated with sea or water in modern Norwegian dictionaries.[25] The "Sea-mischief" appears in the English translation[26] but is absent in the original.[27]

- ^ Although "eight-armed cephalopods", Swedish: åttaarmade bläckfiskar, is a more common synonym.

- ^ Kräkel has also been used to describe Potamogeton Vaill (pondweed)[30] and Zostera Lin (marine eelgrass),[31] etc.

- ^ The two are changing forms of just one beast, which has both tusks and protrusible horns to protect its large eyes, according to Olaus's book.[38]

- ^ And other fabulous-seeming creatures, such as monstrum marinum, bellua marina omnium vastissima, etc.

- ^ Machan quoted Egede's text proper regarding some sort of "Bæst"[19] or "forfærdelige Hav-Dyr [terrible sea-animal]" witnessed in the Colonies (Greenland),[23] but ignored the footnote which tells much on the krake. Ruickbie quoted Egede's footnote, but decided to place it under his entry for "Hafgufa".[55]

- ^ Reference to the sea spectre ("phantom") was added in the English margin header: "A Norway Tale of Kraken, a pretended phantom",[60] but that reference is wanting in the Danish original. It was already noted that the original wording localizes the legend specifically to Nordlandene len, not Norway altogether.

- ^ Speculum Regale Islandicum after Thormodus Torfæus, as elocuted by Egede. The Speculum contains a detailed digression about whales and seals in the seas around Iceland and Greenland,[61] where one finds description of the hafgufa.

- ^ Bushnell speaks of Icelandic literature (in the 13th century) also, but strictly speaking, Örvar-Odds saga contains the mention of hafgufa and lyngbakr[69] only in the later recension, dated to the late 14th century.

- ^ Mouritsen & Styrbæk (2018) (book on inkfish) distinguishes the whale lyngbakr with the monster hafgufa.

- ^ Cf. kraken aka "the crab-fish" (Swedish: Krabbfisken) described by Swedish magnate Jacob Wallenberg in Min son på galejan ("My son on the galley", 1781):

Kraken, also called the crab-fish, which is not that huge, for heads and tails counted, he is reckoned not to overtake the length of our Öland off Kalmar [i.e., 85 mi or 137 kilometres] ... He stays at the sea floor, constantly surrounded by innumerable small fishes, who serve as his food and are fed by him in return: for his meal, (if I remember correctly what E. Pontoppidan writes,) lasts no longer than three months, and another three are then needed to digest it. His excrements nurture in the following an army of lesser fish, and for this reason, fishermen plumb after his resting place ... Gradually, Kraken ascends to the surface, and when he is at ten to twelve fathoms [18 to 22 m; 60 to 72 ft] below, the boats had better move out of his vicinity, as he will shortly thereafter burst up, like a floating island, gushing out currnts like at Trollhättan [Trollhätteströmmar], his dreadful nostrils and making an ever-expanding ring of whirlpool, reaching many miles around. Could one doubt that this is the Leviathan of Job?[91][92]

- ^ This is called arbor marinus by Denys-Montfort, and equated with his kraken octopus, as discussed below.

- ^ Actually there is even the species "Gorgon's head" Astrocladus euryale, whose old name was Asterias euryale,[120] which Blumenbach claimed was one of the species that Scandinavian naturalists considered kraken's children.[121] But A. euryale inhabits South African waters. Blumenbach also named Euryale verrucosum, old name of Astrocladus exiguus[122] which occur in the Pacific.

- ^ The ozaena nickname as literally 'stinkard' for the octopus on account of its reek is given in the side-by-sidy translation by Gerhardt. The polypus of Carteia tract, is thus given, but the Latin quoted by Pontoppidan "Namque et afflatu terribli canes agebat..." is blanked Gerhardt and only given in modern English, "were pitted against something uncanny, for by its awful breath it tormented the dogs, which it now scourged with the ends of its tentacles".. because it represents an interpolation by Pliny.

- ^ Lovén gave the text as tegmen ex heterogeneis compilatis,[140] but this reading occurs in the Latin-Swedish 6th edition of 1748.[156] Whereas the 2nd edition has "testa" instead of "tegmen".[157]

- ^ Lóven indicates that these sources appeared in print in the second edition of SN, but as a piece of marginalia, he notes these sources were also given in Linnaeus's 1733 lectures.[140] The lecture was preserved in the Notes taken by Mennander, held by the Royal Library, Stockholm.[158]

- ^ "Meer=Trauben" already appeared in the 1740 Latin-German edition.[155] The 9th edition of 1956, which is said to be the same as the 6th edition,[162] also leaves a blanc instead of adding the French vernacular name.[165]

- ^ An illustration of sea-grapes (French: raisins de mer) appears on Moquin-Tandon (1865), p. 309.

- ^ As noted previously, Sepia genus represents cuttlefish in modern taxonomy, Linnaeus's genus Sepia was essentially "cephalopods", and his Sepia octopodia was the common octopus.[166][167]

- ^ See the black and white woodcut reprodcution, Fig., right (Actually from Lee (1883), a different book; the same picture, without caption appears in the 1890 book.

- ^ However, elsewhere on the map, the giant lobster is called a lobster (Medieval Latin: gambarus > Latin: cammarus > Ancient Greek: κάμμαρος) in the legend; this is the one shown struggling with a one-horned beast.[192]

- ^ Iona is of course associated with the Irish saints, Columcille and St. Brendan.

- ^ This fish has a name: Jasconius.

- ^ Hugo also produced an ink and wash sketch of the octopus.[214]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Montgomery, Sy (2016). JThe Soul of an Octopus: A Surprising Exploration into the Wonder of Consciousness. Simon and Schuster. p. note 13. ISBN 9781501161148.

- ^ a b c Denys-Montfort (1801), p. 256, Pl. XXVI.

- ^ a b Pennant, Thomas (1777). "Sepia". British ZoologyIV: Crustacea. Mollusca. Testacea. Benjamin White. pp. 44–45.

- ^ a b c d e f g Packard, A. S. (March 1872). "Kraken". The Connecticut School Journal. 2 (3): 78–79. JSTOR 44648937.

- ^ a b c Hamilton (1839). Plate XXX, p. 326a.

- ^ a b "kraken". Oxford English Dictionary. Vol. V (1 ed.). Oxford University Press. 1933. p. 754.

Norw. kraken, krakjen, the -n, being the suffixed definite article

= A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles (1901), V: 754 - ^ a b c d "kraken". Bokmålsordboka | Nynorskordboka.

- ^ a b c d e "krake sbst.4". saob.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "krake sbst.1". saob.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ "krake sbst.2". saob.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ a b c [Anonymous] (1849). (Review) New Books: An Essay on the credibility of the Kraken. The Nautical Magazine 18(5): 272–276.

- ^ Cleasby & Vigfusson (1874), An Icelandic-English Dictionary, s.v. "https://books.google.com/books?id=ne9fAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA354&q=kraki+kraki" '[Dan. krage], a pole, stake'

- ^ a b "krake sbst.2". saob.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "krake sbst.3". saob.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Finnur Jónsson (1920), pp. 113–114.

- ^ a b c "Nordisk familjebok / 1800-talsutgåvan. 8. Kaffrer - Kristdala /". runeberg.org. 1884. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ a b c Pontoppidan (1753a), p. xvi(?)

- ^ a b c Pontoppidan (1753a), p. 340.

- ^ a b c d e Machan, Tim William (2020). "Ch. 5. Narrative, Memory, Meaning /§Kraken". Northern memories and the English Middle Ages. David Matthews, Anke Bernau, James Paz. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-1-5261-4537-6.

- ^ a b Pontoppidan (1755), p. 210.

- ^ a b Metropolitana (1845), p. 256.

- ^ W[ilson] (1818), p. 647.

- ^ a b c Egede (1741), p. 49.

- ^ Knudsen, Knud (1862). Er Norsk det samme som Dansk?. Christiania: Steenske Bogtrykkeri. p. 41).

- ^ "draug". Bokmålsordboka | Nynorskordboka.

- ^ Pontoppidan (1755), p. 214.

- ^ Pontoppidan (1753a), pp. 346–347: Danish: .. krake, hvilken nongle Søe-fokl ogsaa kalde Søe-Draulen, det er Søe-Trolden

- ^ "kräkel sbst.1". saob.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Kräkel". havet.nu. Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ^ "kräkel sbst.3". saob.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ^ "kräkel sbst.4". saob.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ^ "kräkla sbst.2". saob.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ^ Jakobsen, Jakob (1921), "krekin, krechin", Etymologisk ordbog over det norrøne sprog på Shetland, Prior, p. 431; Cited in Collingwood, W. G. (1910). Review, Antiquary 46: 157

- ^ Olaus Magnus (1887) [1539]. "Die ächte Karte des Olaus Magnus vom Jahre 1539 nach dem Exemplar de Münchener Staatsbibliothek". In Brenner, Oscar [in German] (ed.). Forhandlinger i Videnskabs-selskabet i Christiania. Trykt hos Brøgger & Christie. p. 7.

monstra duo marina maxima vnum dentibus truculentum, alterum cornibus et visu flammeo horrendum / Cuius oculi circumferentia XVI vel XX pedum mensuram continet

- ^ a b Gesner, Conrad (1670). Fisch-Buch. Gesnerus redivivus auctus & emendatus, oder: Allgemeines Thier-Buch 4. Frankfurt-am-Main: Wilhelm Serlin. pp. 124–125.

- ^ a b Nigg, under "Kraken".[179] Nigg references the beasts labeled "D" in Sebastian Münster's "Monstra Marina"[180] and confusingly states that Münster's key "D" "repeats Olaus's key", but by visual comparison it is unmistakable that the two beasts in question are the two beasts labeled "B" in Olaus's map (shown in the figure above/right).

- ^ a b Cf. Machan (2020): "Olaus Magnus's magnificent sixteenth-century Carta Marina is replete with imagery of krakens.. (See Figure 3.)"

- ^ a b c Olaus Magnus (1998). Foote, Peter (ed.). Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus: Romæ 1555 [Description of the Northern Peoples : Rome 1555]. Fisher, Peter;, Higgens, Humphrey (trr.). Hakluyt Society. p. 1092. ISBN 0-904180-43-3.

- ^ Eberhart, George M. (2002). "Kraken". Mysterious Creatures: A Guide to Cryptozoology. ABC-CLIO. p. 282ff. ISBN 1-57607-283-5.

- ^ Beck, Thor Jensen (1934), Northern Antiquities in French Learning and Literature (1755-1855): A Study in Preromantic Ideas, vol. 2, Columbia university, p. 199, ISBN 5-02-002481-3,

Before Pontoppidan, the same " Krake " had been taken very seriously by the Italian traveler, Francesco Negri

- ^ Negri, Francesco (1701) [1700], Viaggio settentrionale (in Italian), Forli, pp. 184–185,

Sciu-crak è chiamato un pesce di smisurata grandezza, di figura piana, rotonda, con molte corna o braccia alle sue estremità

- ^ Sturluson, Snorri (1916). The Prose Edda. The American-Scandinavian Foundation.

- ^ a b c Egede (1741). p. 48: "Det 3die Monstrum, kaldet Havgufa som det allerforunderligte, veed Autor ikke ret at beskrive" p. 49: " af dennem kaldes Kraken, og er uden Tvil den self jamm; som Islænderne kalde Havgufa"; Egede (1745). p. 86: "The third monster, named Hafgufa.. the Author does not well know ow to describe.. he never had any relation of it." p. 87: "Kracken.. no doubt the same that the Islanders call Hafgufa"

- ^ a b Halldór Hermannsson (1938), p. 11: Speculum regiae of the 13th century describes a monstrous whale which it calls hafgufa... The whale as an island was, of course, known from the Saga of St. Brandan, but there it was called Jaskonius".

- ^ Pontoppidan (1753a) (Danish); Pontoppidan (1755) (English); vid. infra.

- ^ Bushnell (2019), p. 56: "Nineteenth-century English interest in the Kraken stems from Linnaeus's discussion of the creature in the first edition of Systema Naturae (1735) and most famously from Natural History of Norway (1752-3) by the Bishop.. Pontoppidan (translated into English soon after)".

- ^ Oudemans (1892), p. 414.

- ^ Anderson, Rasmus B. (1896). "Kra'ken". Johnson's Universal Cyclopædia. Vol. 5 (new ed.). D. Appletons. p. 26.

- ^ Müller (1802), p. 594: "Der norwegische Bischoff Pontoppidan ist der erster, welcher uns einer umständliche und deutsche Nachricht von diesem Seethier gegeben hat".

- ^ a b Kongelige nordiske oldskrift-selskab, ed. (1845). Grönlands historiske Mindesmaerker. Vol. 3. Brünnich. p. 371, note 52).

- ^ Pilling, James Constantine (1885). Proof-sheets of a Bibliography of the Languages of the North American Indians. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of Ethnology: Miscellaneous publications 2. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 226–227.

- ^ Egede (1741), p. 49 (footnote).

- ^ The marginal header in the original is "Fabel om Kraken i Nordlandene"[52] which refers specifically to the len of Nordland under Danish rule; this is not just modern Norway's Nordland county, but includes the counties that lies farther north. Egede was born in Harstad, in Nordland (len) during his life. The town is now part of Troms Finnmark, Norway.

- ^ a b Egede (1741), pp. 48–49 (footnote); Egede (1745), pp. 86–87 (footnote) (English); Egede (1763), pp. 111–113(footnote) (German)

- ^ Ruickbie, Leo (2016). "Hafgufa". The Impossible Zoo: An encyclopedia of fabulous beasts and mythical monsters. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-1-4721-3645-9.

- ^ Nyrop, Kristoffer [in Danish] (1887), "Navnets mag: en folkepsykologisk studie", Opuscula Philologica: Mindre Afhandlinger, Copenhagen: Filologisk-historiske Samfund: 182

- ^ a b Egede (1745), p. 88 (footnote).

- ^ Kvam, Lorentz Normann [in Norwegian] (1936), "krekin, krechin", Trollene grynter i haugen (in Norwegian), Nasjonalforlaget, p. 131,

Den sier at med ekte troll forståes : a ) jutuler og riser, b ) gjengangere og spøkelser, - c ) nisser og dverger, d ) bergtroll

- ^ The Norwegian trold (troll) can signify not just a giant, but spøkelser as well.[58]

- ^ Egede (1745), p. 87 (footnote).

- ^ Guðbrandur Vigfússon, ed. (1878). Sturlunga Saga: Including the Islendinga Saga. Vol. 1. Clarenden Press. p. 139.

- ^ Egede (1741), p. 47.

- ^ Egede (1741), p. 85.

- ^ Crantz, David [in German] (1820). The History of Greenland: Including an Account of the Mission Carried on by the United Brethren in that Country. From the German of David Crantz. Vol. 1. p. 122.; Cf. Note X, pp. 323–338

- ^ W[ilson] (1818), p. 649.

- ^ "XXII. The Marvels of the Icelandic Seas: whales; the kraken", The King's Mirror: (Speculum Regalae - Konungs Skuggsjá), Library of Scandinavian literature 15, translated by Larson, Laurence Marcellus, Twayne Publishers, 1917, p. 125, ISBN 978-0-89067-008-8

- ^ Keyser, Rudolf; Munch, Peter Andreas; Unger, Carl Richard, eds. (1848), "Chapter 12", Speculum Regale. Konungs-Skuggsjá, Oslo: Carl C. Werner & Co., p. 32

- ^ Somerville, Angus A.; McDonald, R. Andrew, eds. (2020) [2019], "Wonders of the Iceland sea", The Viking Age: A Reader, translated by Somerville, Angus A. (3 ed.), University of Toronto Press, p. 308, ISBN 978-1-4875-7047-7

- ^ Halldór Hermannsson (1938); Halldór Hermannsson [in Icelandic] (1924), "Jón Guðmundsson and his natural history of Iceland", Islandica, 15: 36, endnote to p. 8

- ^ a b Bushnell (2019), p. 56.

- ^ Mouritsen, Ole G. [in Danish]; Styrbæk, Klavs (2018). Blæksprutterne kommer. Spis dem!. Gyldendal A/S. ISBN 978-87-02-25953-7.

- ^ Fisher, Peter (2006). Historia Norwegie. Museum Tusculanum Press University of Copenhagen. p. 57.

- ^ Kongelige nordiske oldskrift-selskab (1845), p. 372.

- ^ Larson, Laurence (1917). The King's Mirror (Speculum Regale Konungs Skuggsjá)). Twayne Publishers Inc., New York and The American-Scandinavian Foundation.

- ^ Pontoppidan (1753a); Pontoppidan (1753b) (German); Pontoppidan (1755) (English)

- ^ Hamilton (1839), pp. 329–330.

- ^ Metropolitana (1845), pp. 255–256.

- ^ Bringsværd, T.A. (1970). The Kraken: A slimy giant at the bottom of the sea. In: Phantoms and Fairies: From Norwegian Folklore. Johan Grundt Tanum Forlag, Oslo. pp. 67–71.

- ^ a b Hamilton (1839), pp. 328–329.

- ^ Pontoppidan (1753b), p. 343: "Male-Strømmen ved Moskøe"; tr. Pontoppidan (1755), p. 212: "the current of the river Male".

- ^ a b c "Kraken". Encyclopædia Perthensis; or Universal Dictionary of the Arts, Sciences, Literature, &c.. 12 (2nd ed.). John Brown, Edinburgh. 1816. pp. 541–542.

- ^ Pontoppidan (1753b), p. 342: Danish: Orlogs-skib; Pontoppidan (1755), p. 212: "largest man of war".

- ^ a b Sjögren, Bengt (1980). Berömda vidunder. Settern. ISBN 91-7586-023-6 (in Swedish)

- ^ Pontoppidan (1755), p. 212.

- ^ Lee (1884), p. 332.

- ^ Pontoppidan (1753a), pp. 344: "bruge paa Sneglenes Maade, med at strekke dem hid og did"; Pontoppidan (1755), p. 213: "use [long arms, or antennae] like the Snail, in turning about".

- ^ Müller (1802), p. 595: "... mit denen es sowohl sich bewegt".

- ^ Bartsch, Paul (1917). "Pirates of the Deep―Stories of the Squid and Octopu". Smithsonian Report for 1916. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. pp. 364–368.

- ^ Finnur Jónsson (1920), p. 114. Norwegian: "kjempebleksprut"; cf. da:Kæmpeblæksprutte.

- ^ Machan (2020): "In other words, Pontoppidan imagines the kraken as a kind of giant crab, although he, too, allows that the animal is largely unwitnessed and unknown.

- ^ Wallenberg, Jacob [in Swedish] (1836), "kapitele (ch. 17): Om en rar fisk", Min son på galejan, eller en ostindisk resa innehållande allehanda bläckhornskram, samlade på skeppet Finland, som afseglade ifrån Götheborg i Dec. 1769, och återkom dersammastädes i Junii 1771 (in Swedish), Stockholm: A. G. Hellsten, p. 163,

Det ar kraken, eller den så kallade krabbfisken,.. lär han ej vara längre än vårt Öland utanför Calmar..

. The last paragraph that the remnants of the Swedish Pomeranian army may be able to haul a specimen if one could be obtained is curtailed in the Stockholm: A. G. Hellsten, 1836 edition Kap. XVII, pp. 44–45 - ^ Cf. Wallenberg, Jacob [in Swedish] (1994), My Son on the Galley, Peter J. Graves (tr.), Chester Springs, PA: Dufour Editions, pp. 56–58, ISBN 1-870041-23-2,

It is the kraken, the so - called crabfish, which is said to visit these waters occasionally . It is not large since, even including the head and the tail, it is not reckoned to be any longer than our island of Öland off Kalmar..

- ^ a b c Stöhr, S.; O'Hara, T.; Thuy, B., eds. (2021). "Astrophyton linckii Müller & Troschel, 1842". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ a b Lyman (1865), p. 190.

- ^ Palomares ML, Pauly D, eds. (2022). "Gorgonocephalus caputmedusae" in SeaLifeBase. January 2022 version.

- ^ Stöhr, S.; O'Hara, T.; Thuy, B., eds. (2022). "Gorgonocephalus eucnemis (Müller & Troschel, 1842)". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ a b Bell, F. Jeffrey (November 1891), "XLIV. Some Notes on British Ophiurids", Annals and Magazine of Natural History, Sixth Series (47): 342–344

- ^ a b Palomares ML, Pauly D, eds. (2022). "Gorgonocephalus eucnemis" in SeaLifeBase. January 2022 version.

- ^ Pontoppidan (1753a), pp. 349–350; Pontoppidan (1755), p. 215–216

- ^ a b Heuvelmans (2015), p. 124.

- ^ Heuvelmans (2015), p. 124: "..it cannot pass through the Pillars of Hercules; he sees in it an obscure allusion" to the kraken.

- ^ Buckland, Francis Trevelyan (1876). Log-book of a Fisherman and Zoologist. Chapman & Hall. p. 209.

- ^ Gesner, Conrad (1575). Fischbuch, das ist ein kurtze ... Beschreybung aller Fischen. Zürich: Christoffel Froschower. p. cx and illustr. opposite.

- ^ Linnaeus's polypus is 'octopus' and glossed thus by Heuvelmans, but since Pontoppidan resorts to variant spellings such as polype, this could lead to confusion. Gessner's polypus was an octopus as well.[102][103]

- ^ Heuvelmans (2015), p. 124 actually only vaguely distinguishes it as "ophiurid" (order Ophiurida).

- ^ a b Lyman (1865), p. 14.

- ^ Hurley, Desmond Eugene (1957). Some Amphipoda, Isopoda and Tanaidacea from Cook Strait. Zoology Publications from Victoria University of Wellington, 21. Victoria University of Wellington. pp. 2, 40.

- ^ WoRMS database for A. linckii,[93] etc.

- ^ Stella Arborescens was later classed in the old-Astrophyton genus containing several species,[106][107] but it would now be obsolete to say Stella Arborescens belongs to the Astrophyton genus which now admits only a single New World species. One genus that would be applicable would be Gorgonocephalus because the 3 species A. linckii, A. eucnemis, A. lamarcki which occur in northern Europe according to Lyman,[106] all of which are given modern accepted assignments as Gorgonocephalus spp.[108]

- ^ Pontoppidan (1755), p. 216.

- ^ The London Magazine, or, Gentleman's Monthly Intelligencer, Vol. 24 (Appendix, 1755). pp. 622–624.

- ^ The original passage in the English translation reads:

the Kraken ... with his many large horns or branches, as it were springing up from its body, which is round ... Both these descriptions [arbor and kraken] confirm my former suppositions, namely, that this Sea-animal belongs to the Polype or Star-fish species ... It seems to be of that Polypus kind which is called by the Dutch Zee-sonne, by Rondeletius and Gessner Stella Arborescens.[110][111]

- ^ Heuvelmans (2015), p. 78.

- ^ Heuvelmans (2015), p. 124: "From the vague description given by the fishermen, it was just as legitimate to see in the kraken a giant ophiurid as a giant cephalopod".

- ^ Pontoppidan (1753a), p. 350; Pontoppidan (1755), p. 216

- ^ Pontoppidan noted that Medusa's head (Lat. pl. capita Medusæ) is identified as Stella Arborescens by the naturalist Griffith Hughes.

- ^ Bergen (1761), pp. 147–149.

- ^ a b Heuvelmans (2015), p. 126.

- ^ Heuvelmans refers to "Gorgon's head",[118] which conservatively speaking refers to family Gorgonocephalidae, but there is also the Gorgonocephalus genus, of which G. caputmedusae is the modern accepted name of Astrophyton linckii[93] which Lyman hesitantly guesses may be Linnaeus's "Medusa's head"[?],[94] and G. eucnemis was F. J. Bell's prime candidate for the proper name of "Shetland Argus", which he thought may be unreliably referred to by Linnaeus and Pontoppidan by the name of Asterias caput-medusæ.[97]

- ^ Stöhr, S.; O'Hara, T.; Thuy, B., eds. (2021). "Asterias euryale Retzius, 1783". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ a b Metropolitana (1845), p. 258: German physician Blumenbach summarized on what the "Northern Naturalist consider.. the young of the Kraken", and added Asterias euryale and "Euryale Verrucosum of Lamarack" to the list.

- ^ a b Stöhr, S.; O'Hara, T.; Thuy, B., eds. (2022). "Euryale verrucosum Lamarck, 1816". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ Palomares ML, Pauly D, eds. (2022). "Astrocladu exiguus" in SeaLifeBase. January 2022 version.

- ^ Euryale verrucosum Lamarck is matched to accepted name Astrocladus exiguus,[122] which occurs in the Pacific.[123]

- ^ Pontoppidan (1753a), pp. 351–352; Pontoppidan (1755), p. 217

- ^ Gerhardt, Mia I. (1966). "Knowledge in decline: Ancient and medieval information on "ink-fishes" and their habits". Vivarium. 4: 151, 152. doi:10.1163/156853466X00079. JSTOR 41963484.

- ^ Denys-Montfort (1801), pp. 256, 258–259.

- ^ Naturalis Historiae lib. ix. cap. 30 apud Lee (1875), pp. 99, 100–103 and Montfort, ibid.

- ^ Nigg (2014), p. 148.

- ^ Gerhardt (1966), p. 152.

- ^ Natural History, Book IX, Loeb edition. According to Pliny's source, Trebius Niger: "..for it struggles with him by coiling round him and it swallows him with sucker-cups and drags him asunder by its multiple suction, when it attacks men that have been shipwrecked or are diving".[129][130]

- ^ cf. Ashton (1890), pp. 264–265

- ^ a b Wilson, Andrew, FRSE (February 1887a). "Science and Crime, and other essay". The Humboldt Library of Science (88): 23.

- ^ Denys-Montfort (1801), p. 386.

- ^ a b Lee (1875), p. 100.

- ^ Denys-Montfort (1801), p. 386, note (1) Arbor marinus.

- ^ Denys-Montfort (1801), p. 386, note (1)

- ^ a b Mitchill (1813), p. 405.

- ^ a b c Paullinus, Christianus Franciscus (1678). "Obs . LI: De Singulari monstro marino". Miscellanea curiosa sive Ephemeridum medico -physicarum germanicarum Academiæ naturae curiosorum. Vol. Ann. VIII. Vratislaviae et Bregae. p. 79.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lovén, Sven (1887). On the Species of Echinoidea Described by Linnaeus in His Museum Ludovicae Ulricae. Stockholm: Kungliga Boktryckeriet P. A. Norstedt & Söner. pp. 20–21, note 2.

- ^ Heuvelmans (2015), p. 91.

- ^ Denys-Montfort (1801), p. 270–278: "nouveau testament attribué a Saint-Thomas" (p. 276)

- ^ a b Lee (1875), pp. 100–103.

- ^ Nigg (2014), p. 147: "The hand-colored woodcut is a reproduction of art in the Church of St. Malo in France".

- ^ Hamilton (1839), pp. 331–332 and Plate XXX, p. 326a

- ^ Packard: "Denys Montfort took the cue, and.. represented a "kraken octopod" in the act of scuttling a three-master.."[4]

- ^ Denys-Montfort (1801), p. 331.

- ^ Denys-Montfort (1801), pp. 358ff, 367–368

- ^ Metropolitana (1845), p. 258.

- ^ a b Lee (1875), pp. 103–105 and note

- ^ d' Orbigny, Alcide (1848). "Poulpe colossal / Sepia gigas". Histoire naturelle générale et particulière des Céphalopodes acétabulifères vivants et fossiles: Texte. Vol. 1. J. B. Baillière. p. 143.: "Si nous Poulpe Colossal est admis, à la seconde édition je lui ferai renverser une escadre".

- ^ Lee (1875), p. 103.

- ^ Mitchill (1813), pp. 396–397. Captioned Sepia octopus. Mitchill (1813), p. 401: Linnaeus's Sepia octopus is explained to be the eight-armed animal called poulpe commun by the French, and which was neither the cuttlefish which have scales, nor squid which have plated.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carolus (1735). Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ (1 ed.). Leyden: Theodorus Haak.

- ^ a b Linnaeus, Carolus (1740). Langen, Johann Joachim (tr.) (ed.). Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ [Natur=Systema, oder, Drey Reiche der Natur] (1 ed.). Halle: Gebauer. p. 68.

Corpus variis heterogeneis tectum. Microcosmus marinus. Der Leib ist mit verschiedenen fremden Theilchen bedeckt. Die meer=Traube

- ^ a b Linnaeus, Carolus (1748). Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ (6 ed.). Stockholm: Gottfr. Kiesewetter. p. 78. (in Latin) (in Swedish)

- ^ a b Linnaeus, Carolus (1740). Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ (2 ed.). Stockholm: Gottfr. Kiesewetter. p. 64.

- ^ Lovén (1887), p. 14, note 2.

- ^ a b Bartholin, Thomas (1657). "Historia XXIV. Cetorum genera". Thomae Bartholini historiarum anatomicarum rariorum centuria [III et ]IV (in Latin). typis Petri Hakii, acad. typogr. p. 283.

- ^ Redi, Francesco (1684). Osservazioni intorno agli animali viventi che si trovano negli animali viventi. Christoph Günther. pp. 61, 217–218. and Tab. 21

- ^ Redi, Francesco (1686). "Observationes Franisci Redi circa animalia viventia, quae reperiuntur in animalibus viventibus. Florentiae apud P. Batini 1684 in 4to". Acta eruditorum. Christoph Günther. p. 84.

- ^ a b c "Linné (Carl von)". Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. Smithsonian Institution. 1874. pp. 31–32.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carolus (1748). Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ (7 ed.). Leipzig: Gottfr. Kiesewetter. p. 75. (in Latin) (in German)

- ^ Heuvelmans, Bernard (2015) [2006]. Kraken & The Colossal Octopus. Routledge. pp. 117–118. ISBN 978-1-317-84701-4.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carolus (1756). Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ (9 ed.). Leyden: Theodorus Haak. p. 82. (in Latin) (in French)

- ^ Heuvelmans (2015), p. 147?.

- ^ Mitchill (1813), pp. 402–203: "[Mr. Montfort's].. gigantic Sepia.. [which he] calls Colossal". Also Mitchill, passim. gives Sepia octopus (recté octopodia).

- ^ Figuier, Louis [in French] (1866). La vie et les moeurs des animaux zoophytes et mollusques par Louis Figuier. Paris: L. Hachette et C.ie. p. 463.

- ^ Heuvelmans (2015), p. 118, note 2: "..incorrectly claimed, following Louis Figuier (1860) and later Alfred Moquin-Tandon (1865) that Linnaeus had classified the kraken as the cephalopod Sepia microcosmus. This is completely false.

- ^ Ellis, Richard (2006). Singing Whales and Flying Squid: The Discovery Of Marine Life. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 143. ISBN 1-4617-4896-8.

- ^ The notion that Linnaeus mentioned the kraken in 1735 has been taken to be fact by Bushnell (2019), p. 56, and Richard Ellis in 2006 also assumed the Sepia microcosmus was present in the first edition, concluding therefore it was removed by the time a later edition appeared.[170]

- ^ Linnaeus, Carolus (1806), "47. Sepia", A general system of nature, translated by Turton, William, London: Printed for Lackington, Allen, and Co, p. 118

- ^ a b Gibson, John (1887). "Chapter VI: The Legendary Kraken". Monsters of the Sea, Legendary and Authentic. London: T. Nelson. pp. 79–86 (plate, p. 83). Archived from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 19 January 2022 – via Biodiversity.

- ^ Moquin-Tandon (1865), p. 311 also remarks on the pictorial representation of the kraken to "the giant Cephalopods embracing a tall ship in his huge arms, aiming to swallow it", though the work cited is Sonnini de Manoncourt, Suites à Buffon.

- ^ More, A. G. (July 1875), "Notice of a gigantic Cephalopod (Dinoteuthis proboscideus) which was stranded at Dingle, in Kerry, two hundred years ago", Zoologist: A Monthly Journal of Natural History, Second series, 10: 4526–4532

- ^ Heuvelmans (2015), pp. 141–142.

- ^ a b c Olaus Magnus (1555). "Liber XXI. De Polypis: Cap. XXXIIII". Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus. Rome: Giovanni M. Viotto. p. 763.

- ^ Laist, David W. (2017). North Atlantic Right Whales: From Hunted Leviathan to Conservation Icon. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-4214-2098-1.

- ^ Nigg, Joseph (2014). "The Kraken". Sea Monsters: A Voyage around the World's Most Beguiling Map. David Matthews, Anke Bernau, James Paz. University of Chicago Press. pp. 145–146. ISBN 978-0-226-92518-9.

- ^ Münster, Sebastian (1572). "Monstra Marina & terrestria, quam in partibus aquilonis inueniuntur". Cosmographiae vniuersalis lib. 6. in quibus iuxta certioris fidei scriptores, sine omni cuiuscumque molestia, uel laesione, describuntur. Omnium habitabilis orbis partium situs propriaeque dotes. Regionum topographicae picturae. ... pp. 1004–1005.

- ^ Lee, Henry (1883). "The Great Sea Serpent". Sea Monsters Unmasked. The Fisheries Exhibition Literature 3. Chapman and Hall. p. 58.

- ^ Ashton (1890). Curious Creatures p. 244. Ashton continues the discussion on pp. 262–263 using the reproduction of Olaus's woodcut, the same―except for bearing no caption― as fig. right, from Lee's Sea Monsters Unmasked (1883).[181]

- ^ a b Plautius, Caspar (aka Honorius Philoponus) (1621), Nova Typis Transacta Navigatio: Novi Orbis Indiae Occidentalis, pp. 10a–11

- ^ "American-Scandinavian Biography for 1969 Scandinavian Studies 42 (3), . Brief notice of Ashton (1968) [1890], Detroit: Singing Tree Press.

- ^ Ashton (1890), pp. 221–222.

- ^ Ashton (1890), pp. 261–265.

- ^ Ashton (1890), p. 244.

- ^ Ashton (1890), p. 262.

- ^ Ashton (1890), p. 263.

- ^ See fig. above, detail of Carta marina.

- ^ Lee (1884), "Chapter: The Great Sea Serpent", p. 58: "From the crude image of a lobster having eight minor claws.. the transition is not great; and I believe that this also is a pictorial misrepresentation of a casualty by the attack of a calamary above described, .."

- ^ Olaus Magnus (1887) [1539], p. 427

- ^ Olaus Magnus (1887) [1539], p. 12: "G: Totius tabulae indicem partemque regnorum Anglie Scotie et Hollandie demonstrat" is the entire text. There is no description here of the lobster-like monster labeled "M" in the map, unlike other beasts which are described.

- ^ Olaus Magnus (1887) [1539], p. 12, note 5: "..Die geogr. Länge beginnt bald bei Irland, bald bei den Inseln "Fortunate"

- ^ Feest, Christian F. (1986), "Zemes Idolum Diabolicum: Surprise and success in Ethnographic Kunstkammer Research", Archiv für Völkerkunde, 40: 181; snippet via Google.

- ^ The "Insula Fortunate" is situated next to St. Brendan's in the engraving in Caspar Plautius's book (1621),[183] engraved by Wolfgang Kilian[195]

- ^ Lee (1884), pp. 364–366.

- ^ Verrill (1882), pp. 262–267.

- ^ Verrill (1882), pp. 213, 410.

- ^ Rogers, Julia Ellen (1920). "The Giant Squids: Genus Architeuthis, Steenstrup". The Shell Book: a popular guide to a knowledge of the families of living mollusks. The Nature Library 15. Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Company. pp. 456–458.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew, FRSE (1887b). "V. The Past and Present of the Cuttlefishes". Studies in Life and Sense. Chatto & Windus. pp. 108–109.

- ^ Williams, Wendy (2011). Kraken: The Curious, Exciting, and Slightly Disturbing Science of Squid. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 9781613120859.

- ^ Latva, Otto (11 May 2023). The Giant Squid in Transatlantic Culture: The Monsterization of Molluscs (1 ed.). London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003311775. ISBN 978-1-003-31177-5.

- ^ Perkins, Sid (2011). "Kraken versus ichthyosaur: let battle commence". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2011.586. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ McMenamin, Mark A. S.; McMenamin, Dianna Schulte (October 2011). "Triassic Kraken: The Berlin Ichthyosaur Death Assemblage Interpreted as a Giant Cephalopod Midden". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 43 (5): 310. Archived from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- ^ McMenamin, M. A. S.; McMenamin, Dianna Schulte (2013). "The Kraken's back: New evidence regarding possible cephalopod arrangement of ichthyosaur skeletons". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 43 (5): 87.

- ^ McMenamin, Mark A. S. (2023). "A Late Triassic Nuculanoid Clam (Bivalvia: Nuculanoidea) and Associated Mollusks: Implications for Luning Formation (Nevada, USA) Paleobathymetry". Geosciences. 13 (3): 80. Bibcode:2023Geosc..13...80M. doi:10.3390/geosciences13030080. ISSN 2076-3263.

- ^ "The Meniscus: The Kraken Sleepeth". 16 October 2011.

- ^ Simpson, Sarah (11 October 2011). "Smokin' Kraken?". Discovery News. Discovery Channel. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ "Mythical Kraken-Like Sea Monster Might be Real: Researcher". International Business Times. The International Business Times Inc. 12 October 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ^ Than, Ker (11 October 2011). "Kraken Sea Monster Account "Bizarre and Miraculous"". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 12 October 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ^ Cahill, James Leo (2019). Zoological Surrealism: The Nonhuman Cinema of Jean Painlevé. U of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-1-4529-5922-1.

- ^ Hugo, Victor (1866). Les travailleurs de la mer. Lacroix. p. 88.

- ^ Weiss, Allen S. (2002). "4 The Epic of the Cephalopod". Feast and Folly: Cuisine, Intoxication, and the Poetics of the Sublime. SUNY Press. pp. 73–75. ISBN 0-7914-5518-1.: repr. from Weiss (Winter 2002) in: Discourse 24 (1: Mortals to Death ), Wayne State University Press, pp. 150–159, JSTOR 41389633

- ^ Bhattacharjee, Shuhita (1657). "The Colonial Idol, the Animalistic, and the New Woman in the Imperial Gothic of Richard Marsh". In Heholt, Ruth; Edmundson, Melissa (eds.). Gothic Animals: Uncanny Otherness and the Animal With-Out. Springer Nature. p. 259. ISBN 978-3-030-34540-2.

- ^ Nigg (2014), p. 147.

- ^ Verne, Jules (1993). Miller, Walter James; Walter, Frederick Paul (tr.) (eds.). Jules Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea: The Definitive Unabridged Edition Based on the Original French Texts. Naval Institute Press. p. note 13. ISBN 1-55750-877-1.

- ^ "The Kraken (1830)". Victorianweb.org. 11 January 2005. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ Melville, Herman (2001) [1851]. Moby Dick; Or, The Whale. Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Stowell, Barbara A. (2009). "Under the Sea: The Kraken in Culture". cgdclass.com. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ Miller, T. S. (2011). "From Bodily Fear to Cosmic Horror (and Back Again): The Tentacle Monster from Primordial Chaos to Hello Cthulhu". Lovecraft Annual (5): 121–154. ISSN 1935-6102.

- ^ "Kraken Mare: The Largest Methane Sea Known To Humankind". WorldAtlas. 25 April 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ Stern, A. S.; McKinnon, W. B. (March 1999). Triton's Surface Age and Impactor Population Revisited (Evidence for an Internal Ocean) (PDF). 30th Annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Houston, TX. Bibcode:1999LPI....30.1766S. 1766.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ashton, John (1890). Curious Creatures in Zoology: With 130 Illus. Throughout the Text. London: John C. Nimmo.

- Bergen, Karl August von (1761). "Observatio XXVIII: Microcosmo, bellua marina omnium". Nova acta physico-medica Academiae Caesareae Leopoldino-Carolinae naturae curiosorum exhibentia ephemerides. Vol. 2. impensis Wolfgangi Schwarzkopfii. pp. 143–150.

- Bushnell, Kelly (2019). "Ch. 2 Tennyson's Kraken under the Microscope and in the Aquarium". In Abberley, Will (ed.). Underwater Worlds: Submerged Visions in Science and Culture. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 52–72. ISBN 978-1-5275-2553-5.

- Denys-Montfort, Pierre (1801). "La poulpe colossal – La poulpe kraken". Des mollusques. Histoire naturelle : générale et particulière 102 (in French). Vol. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie de F. Dufart. pp. 256–412.; alt text (Vol. 102) via Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Egede, Hans (1741) [1729]. "Kap. VI. Hvad Slags Diur, Fiske og Fugle den Grønlandske Søe giver af sig etc. / § Andre Søe-Diur". Det gamle Grønlands nye perlustration,. (in Danish). Copenhagen: Groth. pp. 48–49 (footnote). digital copy@National Library Norway. modern typeset reprint (1926) A.W. Brøggers boktrykkeris forlag.

- —— (1745). "Ch. 6. Of the Greenland Sea Animals, and Sea Fowl and Fishes / § Of other Sea Animals". A description of Greenland : Shewing the natural history, situation, boundaries and face of the country, the nature of the soil;. London: Printed for C. Hitch in Pater-noster Row; S. Austen in Newgate-Street; and J. Jackson near St. James's Gate. pp. 86–87. digital copy@National Library Norway

- —— (1763) [1730]. "Das 6te Capitel: von denen Thieren, Fischen, Vögeln, u.s.f. welche sich in denem Grönländischen Meeren finden". Herrn Hans Egede, Mißionärs und Bischofes in Grönland, Beschreibung und Natur-Geschichte von Grönland (in German). Berlin: Mylius. pp. 111–113 (footnote).

- Finnur Jónsson, ed. (1920). "12". Konungs skuggsjá: Speculum regale. Vol. 2. Reykjavík: I kommission i den Gyldendalske boghandel, Nordisk forlag.

- Halldór Hermannsson [in Icelandic] (1938), "Icelandic Physiologus", Islandica, 27: 4–17

- Hamilton, Robert, M.D., FRSE (1839), "The Kraken", in Jardine, William, Sir (ed.), Amphibious carnivora, including the Walrus and Seals, also of the Herbivorous Cetacea, &c., The Naturalist's Library 25 (Mammalia 11), Lizars, W. H. 1788–1859, engraver, Edinburgh: W. H. Lizars, pp. 327–336. Plate XXX (The Kraken): "The Kraken supposed a sepia or cuttle fish (from Denys Montfort)", p. 326a via Biodiversity.

- Lee, Henry (1875), The Octopus: Or, The "devil-fish" of Fiction and of Fact, London: Chapman and Hall

- —— (1884). "The Kraken". Sea Monsters Unmasked. The Fisheries Exhibition Literature 3. Chapman and Hall. pp. 325–327.

- Lyman, Theodore (1865). Illustrated Catalogue of the Museum of Comparative Zoölogy at Harvard College: Ophiuridæ and Astrophytidæ. Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College, No. 1. Museum of Comparative Zoology. Harvard University Press.

- McMenamin, M.A.S. (2016). Deep Bones. In: M.A.S. McMenamin Dynamic Paleontology: Using Quantification and Other Tools to Decipher the History of Life. Springer, Cham. pp. 131–158. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-22777-1_9 ISBN 978-3-319-22776-4.

- "Kraken", Encyclopædia Metropolitana; or, Universal Dictionary of Knowledge, London: B. Fellowes, 1875, pp. 255–258

- Mitchill, Samuel Latham (1813). "Natural History". The Medical Repository (And Review Of American Publications On Medicine, Surgery And The Auxiliary Of Science). new series. Vol. 1. New York: John Forbes. pp. 396–497.

- Moquin-Tandon, Alfred (1865). Le Monde de la mer (in French). Lackerbauer, P[ierre] (illustr.). Paris: L. Hachette.

- Müller, Wilhelm, Dr., Prof. (1802), "Kraken", Deutsche Encyclopädie oder Allgemeines Real-Wörterbuch aller Künste und Wissenschaften: Ko-Kraz, vol. 22, Frankfurt a. M.: Varrentrapp und Wenner, pp. 594–605

- Oudemans, A. C. (1892). The Great Sea-serpent: An Historical and Critical Treatise. Vol. 1. Lackerbauer, P[ierre] (illustr.). Leiden: E.J. Brill.

- Pontoppidan, Erich (1753a). "Kap. 8. §11. Kraken eller Horven det største dyr i Verden /§12Beskrivelse.". Det første Forsøg paa Norges naturlige Historie (in Danish). Vol. 2. Copenhagen: Berlingske Arvingers Bogtrykkerie. pp. xvi(?), 340–345. digital copy@National Library Norway

- —— (1753b). "Kap. 8. §11. Kraken oder Horven, das größte Thier in der Welt /12. Beschreibung dieses Thieres". Versuch einer natürlichen Geschichte Norwegens (in German). Vol. 2. Copenhagen: Franz Christian Mumme. pp. 394–400.

- —— (1755). "Ch. 8. Sect. 11. Kraken, or Korven [sic.], the largest creature in the world /Sect. 12. Description". The Natural History of Norway...: Translated from the Danish Original. Vol. 2. London: A. Linde. pp. 210–213.

- Verrill, A. E. (1882), "Report on the Cephalopods of the Northeastern Coast of America", Report of the Commissioner, vol. 7, United States Fish Commission, pp. 211–436

- W[ilson], [James] (March 1818). "Remarks on the histories of the kraken and great sea serpent". Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine. 2 (12). William Blackwood: 645-654.