Generation

A generation is all of the people born and living at about the same time, regarded collectively.[1] It also is "the average period, generally considered to be about 20–30 years, during which children are born and grow up, become adults, and begin to have children."[2] In kinship, generation is a structural term, designating the parent–child relationship. In biology, generation also means biogenesis, reproduction, and procreation.

Generation is also a synonym for birth/age cohort in demographics, marketing, and social science, where it means "people within a delineated population who experience the same significant events within a given period of time."[3] The term generation in this sense, also known as social generations, is widely used in popular culture and is a basis of sociological analysis. Serious analysis of generations began in the nineteenth century, emerging from an increasing awareness of the possibility of permanent social change and the idea of youthful rebellion against the established social order. Some analysts believe that a generation is one of the fundamental social categories in a society; others consider generation less important than class, gender, race, and education.

Etymology

[edit]The word generate comes from the Latin generāre, meaning "to beget".[4] The word generation as a group or cohort in social science signifies the entire body of individuals born and living at about the same time, most of whom are approximately the same age and have similar ideas, problems, and attitudes (e.g., Beat Generation and Lost Generation).[5]

Familial generation

[edit]

A familial generation is a group of living beings constituting a single step in the line of descent from an ancestor.[6] In developed nations the average familial generation length is in the high 20s and has even reached 30 years in some nations.[7] Factors such as greater industrialisation and demand for cheap labour, urbanisation, delayed first pregnancy and a greater uncertainty in both employment income and relationship stability have all contributed to the increase of the generation length from the late 18th century to the present. These changes can be attributed to social factors, such as GDP and state policy, globalization, automation, and related individual-level variables, particularly a woman's educational attainment.[8] Conversely, in less-developed nations, generation length has changed little and remains in the low 20s.[7][9]

An intergenerational rift in the nuclear family, between the parents and two or more of their children, is one of several possible dynamics of a dysfunctional family. Coalitions in families are subsystems within families with more rigid boundaries and are thought to be a sign of family dysfunction.[10]

Social generation

[edit]Social generations are cohorts of people born in the same date range and who share similar cultural experiences.[11] The idea of a social generation has a long history and can be found in ancient literature,[12] but did not gain currency in the sense that it is used today until the 19th century. Prior to that, the concept "generation" had generally referred to family relationships and not broader social groupings. In 1863, the French lexicographer Emile Littré had defined a generation as "all people coexisting in society at any given time."[13]: 19

Several trends promoted a new idea of generations, as the 19th century wore on, of a society divided into different categories of people based on age. These trends were all related to the processes of modernisation, industrialisation, or westernisation, which had been changing the face of Europe since the mid-18th century. One was a change in mentality about time and social change. The increasing prevalence of enlightenment ideas encouraged the idea that society and life were changeable, and that civilization could progress. This encouraged the equation of youth with social renewal and change. Political rhetoric in the 19th century often focused on the renewing power of youth influenced by movements such as Young Italy, Young Germany, Sturm und Drang, the German Youth Movement, and other romantic movements. By the end of the 19th century, European intellectuals were disposed toward thinking of the world in generational terms—in terms of youth rebellion and emancipation.[13]

One important contributing factor to the change in mentality was the change in the economic structure of society. Because of the rapid social and economic change, young men particularly were less beholden to their fathers and family authority than they had been. Greater social and economic mobility allowed them to flout their authority to a much greater extent than had traditionally been possible. Additionally, the skills and wisdom of fathers were often less valuable than they had been due to technological and social change.[13] During this time, the period between childhood and adulthood, usually spent at university or in military service, was also increased for many white-collar workers. This category of people was very influential in spreading the ideas of youthful renewal.[13]

Another important factor was the breakdown of traditional social and regional identifications. The spread of nationalism and many of the factors that created it (a national press, linguistic homogenisation, public education, suppression of local particularities) encouraged a broader sense of belonging beyond local affiliations. People thought of themselves increasingly as part of a society, and this encouraged identification with groups beyond the local.[13] Auguste Comte was the first philosopher to make a serious attempt to systematically study generations. In Cours de philosophie positive, Comte suggested that social change is determined by generational change and in particular conflict between successive generations.[14] As the members of a given generation age, their "instinct of social conservation" becomes stronger, which inevitably and necessarily brings them into conflict with the "normal attribute of youth"—innovation. Other important theorists of the 19th century were John Stuart Mill and Wilhelm Dilthey.

Generational theory

[edit]The sociologist Karl Mannheim was a seminal figure in the study of generations. He elaborated a theory of generations in his 1923 essay The Problem of Generations.[3] He suggested that there had been a division into two primary schools of study of generations until that time. Firstly, positivists such as Comte measured social change in designated life spans. Mannheim argued that this reduced history to "a chronological table". The other school, the "romantic-historical" was represented by Dilthey and Martin Heidegger. This school focused on the individual qualitative experience at the expense of social context. Mannheim emphasised that the rapidity of social change in youth was crucial to the formation of generations, and that not every generation would come to see itself as distinct. In periods of rapid social change a generation would be much more likely to develop a cohesive character. He also believed that a number of distinct sub-generations could exist.[3] According to Gilleard and Higgs, Mannheim identified three commonalities that a generation shares:[15]

- Shared temporal location: generational site or birth cohort

- Shared historical location: generation as actuality or exposure to a common era

- Shared sociocultural location: generational consciousness or entelechy

Mannheim elaborated on the meaning of a generation's "location" (Lagerung), understood in a historical, economic and sociocultural sense. In 1928 he wrote:[16]

The fact that people are born at the same time, or that their youth, adulthood, and old age coincide, does not in itself involve similarity of location; what does create a similar location is that they are in a position to experience the same events and data, etc., and especially that these experiences impinge upon a similarly 'stratified' consciousness. It is not difficult to see why mere chronological contemporaneity cannot of itself produce a common generation location. No one, for example, would assert that there was community of location between the young people of China and Germany about 1800. Only where contemporaries definitely are in a position to participate as an integrated group in certain common experiences can we rightly speak of community of location of a generation.[17]

From Mannheim's perspective, then, the chronological boundaries often attributed to different generations ("Generation X", "Millennials" etc.) seem to have little global validity since these boundaries are mostly based on shared Western, especially American, historical and sociocultural 'locations'.

Authors William Strauss and Neil Howe developed the Strauss–Howe generational theory outlining what they saw as a pattern of generations repeating throughout American history. This theory became quite influential with the public and reignited an interest in the sociology of generations. This led to the creation of an industry of consulting, publishing, and marketing in the field[18] (corporations spent approximately 70 million dollars on generational consulting in the U.S. in 2015).[19] The theory has alternatively been criticized by social scientists and journalists who argue it is non-falsifiable, deterministic, and unsupported by rigorous evidence.[20][21][22]

There are psychological and sociological dimensions in the sense of belonging and identity which may define a generation. The concept of a generation can be used to locate particular birth cohorts in specific historical and cultural circumstances, such as the "Baby boomers".[12] Historian Hans Jaeger shows that, during the concept's long history, two schools of thought coalesced regarding how generations form: the "pulse-rate hypothesis" and the "imprint hypothesis."[23] According to the pulse-rate hypothesis, a society's entire population can be divided into a series of non-overlapping cohorts, each of which develops a unique "peer personality" because of the time period in which each cohort came of age.[24] The movement of these cohorts from one life-stage to the next creates a repeating cycle that shapes the history of that society. A prominent example of pulse-rate generational theory is Strauss and Howe's theory. Social scientists tend to reject the pulse-rate hypothesis because, as Jaeger explains, "the concrete results of the theory of the universal pulse rate of history are, of course, very modest. With a few exceptions, the same goes for the partial pulse-rate theories. Since they generally gather data without any knowledge of statistical principles, the authors are often least likely to notice to what extent the jungle of names and numbers which they present lacks any convincing organization according to generations."[25]

Social scientists follow the "imprint hypothesis" of generations (i.e., that major historical events—such as the Vietnam War, the September 11 attacks, the COVID-19 pandemic, etc.—leave an "imprint" on the generation experiencing them at a young age), which can be traced to Karl Mannheim's theory. According to the imprint hypothesis, generations are only produced by specific historical events that cause young people to perceive the world differently than their elders. Thus, not everyone may be part of a generation; only those who share a unique social and biographical experience of an important historical moment will become part of a "generation as an actuality."[26] When following the imprint hypothesis, social scientists face a number of challenges. They cannot accept the labels and chronological boundaries of generations that come from the pulse-rate hypothesis (like Generation X or Millennial); instead, the chronological boundaries of generations must be determined inductively and who is part of the generation must be determined through historical, quantitative, and qualitative analysis.[27]

While all generations have similarities, there are differences among them as well. A 2007 Pew Research Center report called "Millennials: Confident. Connected. Open to Change" noted the challenge of studying generations:

Generational analysis has a long and distinguished place in social science, and we cast our lot with those scholars who believe it is not only possible, but often highly illuminating, to search for the unique and distinctive characteristics of any given age group of Americans. But we also know this is not an exact science. We are mindful that there are as many differences in attitudes, values, behaviors, and lifestyles within a generation as there are between generations. But we believe this reality does not diminish the value of generational analysis; it merely adds to its richness and complexity.[28]

Another element of generational theory is recognizing how youth experience their generation, and how that changes based on where they reside in the world. "Analyzing young people's experiences in place contributes to a deeper understanding of the processes of individualization, inequality, and of generation."[29] Being able to take a closer looks at youth cultures and subcultures in different times and places adds an extra element to understanding the everyday lives of youth. This allows a better understanding of youth and the role generation and place play in their development.[30] It is not where the birth cohort boundaries are drawn that is important, but how individuals and societies interpret the boundaries and how divisions may shape processes and outcomes. However, the practice of categorizing age cohorts is useful to researchers for the purpose of constructing boundaries in their work.[31]

Generational tension

[edit]Norman Ryder writing in American Sociological Review in 1965 shed light on the sociology of the discord between generations by suggesting that society "persists despite the mortality of its individual members, through processes of demographic metabolism and particularly the annual infusion of birth cohorts". He argued that generations may sometimes be a "threat to stability" but at the same time they represent "the opportunity for social transformation".[32] Ryder attempted to understand the dynamics at play between generations.

Amanda Grenier in a 2007 essay published in Journal of Social Issues offered another source of explanation for why generational tensions exist. Grenier asserted that generations develop their own linguistic models that contribute to misunderstanding between age cohorts, "Different ways of speaking exercised by older and younger people exist, and may be partially explained by social historical reference points, culturally determined experiences, and individual interpretations".[33]

Karl Mannheim in his 1952 book Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge asserted the belief that people are shaped through lived experiences as a result of social change. Howe and Strauss also have written on the similarities of people within a generation being attributed to social change. Based on the way these lived experiences shape a generation in regard to values, the result is that the new generation will challenge the older generation's values, resulting in tension. This challenge between generations and the tension that arises is a defining point for understanding generations and what separates them.[34]

List of social generations

[edit]Western world

[edit]The Western world includes parts of Western Europe, North America, and Australasia. Many variations may exist within these regions, both geographically and culturally, which means that the list is broadly indicative, but very general. The contemporary characterization of these cohorts used in media and advertising borrows, in part, from the Strauss–Howe generational theory[18][35] and generally follows the logic of the pulse-rate hypothesis.[36]

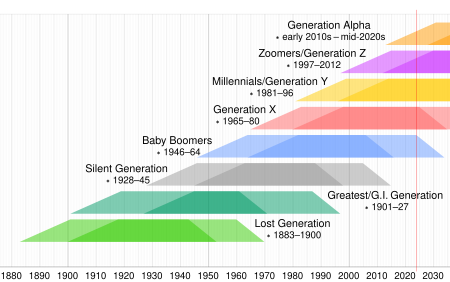

- The Lost Generation, also known as the "Generation of 1914" in Europe,[37] is a term originating from Gertrude Stein to describe those who fought in World War I. The Lost Generation is defined as the cohort born from 1883 to 1900 who came of age during World War I and the Roaring Twenties.[38]

- The Greatest Generation, also known in American usage as the "G.I. Generation",[39] includes the veterans who fought in World War II. They were born from 1901 to 1927;[40] older G.I.s (or the Interbellum Generation) came of age during the Roaring Twenties, while younger G.I.s came of age during the Great Depression and World War II. Journalist Tom Brokaw wrote about American members of this cohort in his book The Greatest Generation, which popularized the term.[41]

- The Silent Generation, also known as the "Lucky Few", is the cohort who came of age in the post–World War II era. They were born from 1928 to 1945.[42][43] In the U.S., this group includes most of those who may have fought in the Korean War and many of those who may have fought during the Vietnam War.

- Baby boomers (often shortened to Boomers) are the people born following World War II from 1946 to 1964. Increased birth rates were observed during the post–World War II baby boom, making them a relatively large demographic cohort.[44][45] In the U.S., many older boomers may have fought in the Vietnam War or participated in the counterculture of the 1960s, while younger boomers (or Generation Jones) came of age in the "malaise" years of the 1970s.[46]

- Generation X (or Gen X for short) is the cohort following the baby boomers. The generation is generally defined as people born between 1965 and 1980.[47] The term has also been used in different times and places for several different subcultures or countercultures since the 1950s. In the U.S., some called Xers the "baby bust" generation because of a drop in birth rates following the baby boom.[48]

- Millennials, also known as Generation Y[49] (or Gen Y for short), are the generation following Generation X, who grew up around the turn of the 3rd millennium.[50] This cohort is generally defined as the people born from 1981 to 1996. The Pew Research Center defines this generation as those born from 1981 to 1996 and reports that in 2019, millennials outnumbered baby boomers in the United States, amounting to an estimated 71.6 million boomers and 72.1 million millennials.[51][52][53][54][55]

- Generation Z (or Gen Z for short and colloquially as "Zoomers"), are the people succeeding the Millennials and are generally defined as being born from 1997 to the early 2010s. Pew Research Center describes Generation Z as spanning from 1997 to 2012.[56] The United States Library of Congress and Statistics Canada have cited Pew's definition of 1997–2012 for Generation Z.[51][52] In a 2022 report, the U.S. Census designates Generation Z as those born from 1997 to 2013.[54] Generation Zers experienced the onset and effects of the COVID-19 pandemic as children or young adults.[57]

- Generation Alpha (or Gen Alpha for short) is the generation succeeding Generation Z. Researchers and popular media typically use the early 2010s as the starting birth year and the mid-2020s as the ending birth year. Generation Alpha is the first to be born entirely in the 21st century.[58] As of 2015, there were some two-and-a-half million people born every week around the globe, and Gen Alpha is expected to reach nearly two billion in size by 2025.[59]

- Generation Beta (or Gen Beta for short) is the proposed generation succeeding Generation Alpha. Futurist Mark McCrindle, who coined the term, defines the cohort as those born from 2025 to 2039.[60][61] As the successor to Generation Alpha, the generation is named for beta, the second letter in the Greek alphabet.

Other areas

[edit]- In Armenia, people born after the country's independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 are known as the "Independence generation".[citation needed]

- In the Czech Republic and Slovakia, the generation of people born in Czechoslovakia during the baby boom which started in the early 1970s, during the period of "normalization" are called "Husák's children". The generation was named after the President and long-term Communist leader of Czechoslovakia, Gustáv Husák.[62] This was due to his political program to boost the growth of population.

- In the People's Republic of China, the "Post-80s" (Chinese: 八零后世代 or 八零后) (born-after-1980 generation) are those who were born in the 1980s in urban areas of mainland China. Growing up in modern China, the Post-80s has been characterised by its optimism for the future, newfound excitement for consumerism and entrepreneurship and acceptance of its historic role in transforming modern China into an economic power.[63] There is also the similarly named "Post-90s" (Chinese: 九零后), those born in the post-Tiananmen era of the 1990s.[64][65] A broader generational classification would be the "one-child generation" born between the introduction of the one-child policy in 1979 and its softening into a "two-child policy" in 2015. The lack of siblings has had profound psychological effects on this generation, such as egoism due to always being at the centre of parents' attention as well as the stress of having to be the sole provider once the parents retire.[citation needed]

- People born post-1980s in Hong Kong are for the most part different from the same generation in mainland China.[66] The term "Post-80s" (zh: 八十後) came into use in Hong Kong between 2009 and 2010, particularly during the opposition to the Guangzhou-Hong Kong Express Rail Link, during which a group of young activists came to the forefront of Hong Kong's political scene.[67] They are said to be "post-materialist" in outlook, and they are particularly vocal in issues such as urban development, culture and heritage, and political reform. Their campaigns include the fight for the preservation of Lee Tung Street, the Star Ferry Pier and the Queen's Pier, Choi Yuen Tsuen Village, real political reform (on 23 June), and a citizen-oriented Kowloon West Art district. Their discourse mainly develops around themes such as anti-colonialism, sustainable development, and democracy.

- In Romania, the term decreței (from the Romanian language word decret, meaning "decree"; diminutive decrețel) is used to refer to those Romanians born during the period immediately following Decree 770 signed in 1967, which restricted abortion and contraception, and was intended to create a new and large Romanian population.[citation needed]

- In Hungary, the re-criminalization of abortion and the childless-tax policies implemented by Anna Ratkó in the early-1950s resulted in a minor baby boom (roughly 1953–1956) known as the "Ratkó era" (hu:Ratkó-korszak) or the "Ratkó children."[68][69]

- In India, generations tend to follow a pattern similar to the broad Western model, although there are still major differences, especially in the older generations.[70] One interpretation sees India's independence in 1947 as India's major generational shift. People born in the 1930s and 1940s tended to be loyal to the new state and tended to adhere to "traditional" divisions of society. Indian "boomers", those born after independence and into the early 1960s, witnessed events like the Indian Emergency between 1975 and 1977 which made a number of them somewhat skeptical of the government.

- In Israel, where most Ashkenazi Jews born before the end of World War II were Holocaust survivors, children of survivors and people who survived as babies are sometimes referred to as the "second generation (of Holocaust survivors)" (Hebrew: דור שני לניצולי שואה, dor sheni lenitsolei shoah; or more often just דור שני לשואה, dor sheni lashoah, literally "second generation to the Holocaust"). This term is particularly common in the context of psychological, social, and political implications of the individual and national transgenerational trauma caused by the Holocaust. Some researchers have also found signs of trauma in third-generation Holocaust survivors.[71]

- In Northern Ireland, people born after the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, generally regarded as the end of the Troubles, are colloquially known as "Peace Babies".[citation needed]

- In Norway, the term "the dessert generation" has been applied to the baby boomers and every generation afterwards.[72]

- In Russia, characteristics of Russian generations are determined by fateful historical events that significantly change either the foundations of the life of the country as a whole or the rules of life in a certain period of time. Names and given descriptions of Russian generations: the Generation of Winners,[73] the generation of the Cold War, the generation of Perestroika, the first non-Soviet generation (the children of Perestroika, the Witnesses of Perestroika), the digital generation.[74]

- In Singapore, people born before 1949 are referred to as the "Pioneer Generation" for their contributions to Singapore during the nation's earliest years. Likewise, those born between 1950 and 1959 are referred to as the "Merdeka Generation" as their formative years were during the political turbulence of the 1950s to 1960s in Singapore.[75]

- In South Africa, people born after the 1994 general election, the first after apartheid was ended, are often referred to in media as the "born-free generation".[76] People born after the year 2000 are often referred to as "Ama2000",[77] a term popularized by music and a Coca-Cola advert.[78]

- In South Korea, generational cohorts are often defined around the democratization of the country, with various schemes suggested including names such as the "democratization generation", 386 generation[79][80] (named after Intel 386 computer in the 1990s to describe people in their late 30s and early 40s who were born in the 1960s, and attended university/college in the 1980s, also called the "June 3, 1987 generation"), that witnessed the June uprising, the "April 19 generation" (that struggled against the Syngman Rhee regime in 1960), the "June 3 generation" (that struggled against the normalization treaty with Japan in 1964), the "1969 generation" (that struggled against the constitutional revision allowing three presidential terms), and the shin-se-dae ("new") generation.[80][81][82] The term Shin-se-dae generation refers to the generation following Millennials in the Korean language. The Shin-se-dae generation are mostly free from ideological or political bias.[83]

- In Spain, although in general terms there is a certain assimilation to the generational structure of Strauss and Howe (and uncritically the majority of the media use it), there are substantial differentials, for historical reasons that (as established by the Generations theory) have marked the successive age cohorts in the Century XX. Firstly, neutrality during the First World War, which prevented it from suffering that social and cultural impact. Secondly, the Civil War and the subsequent dictatorship, which lasted four decades and, especially during its first decades, imposed strong political, social and cultural repression. And thirdly, neutrality during World War II. Thus, the sociologists Artemio Baigorri and Manuela Caballero insert, between the Silent Generation and the Baby Boom Generation (which they also call the Protest Generation), what they call the Franco Generation (1929–1943), whose childhood and early youth was marked by war, post-war scarcity and repression.[84]

- In Taiwan, the term Strawberry generation refers to Taiwanese people born after 1981 who "bruise easily" like strawberries—meaning they can not withstand social pressure or work hard like their parents' generation; the term refers to people who are insubordinate, spoiled, selfish, arrogant, and sluggish in work.[citation needed]

- In the Philippines, the Filipinos who are in Millennials is also known as Batang 90's.[citation needed]

Other terminology

[edit]The term generation is sometimes applied to a cultural movement, or more narrowly defined group than an entire demographic. Some examples include:

- The Stolen Generations, refers to children of Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islander descent, who were forcibly removed from their families by Australian federal and state government agencies and church missions, under Acts of their respective parliaments between approximately 1869 and 1969.[85]

- The Beat Generation, refers to a popular American cultural movement widely cited by social scholars as having laid the foundation of the pro-active American counterculture of the 1960s. It consisted of Americans born between the two world wars who came of age in the rise of the automobile era, and the surrounding accessibility they brought to the culturally diverse, yet geographically broad and separated nation.[86]

- Generation Jones is a term coined by Jonathan Pontell to describe the cohort of people born between 1954 and 1965. The term is used primarily in English-speaking countries.[87][88] Pontell defined Generation Jones as referring to the second half of the post–World War II baby boom.[89] The term also includes first-wave Generation X.

- MTV Generation, a term referring to the adolescents and young adults of the 1980s and early-mid 1990s who were heavily influenced by the television channel MTV. It is often used synonymously with Generation X.[90][91][92]

- In Europe, a variety of terms have emerged in different countries particularly hard hit following the financial crisis of 2007–2008 to designate young people with limited employment and career prospects.[93]

- The Generation of 500 is a term popularized by the Greek mass media and refers to educated Greek twixters of urban centers who generally fail to establish a career. Young adults are usually forced into underemployment in temporary and occasional jobs, unrelated to their educational background, and receive the minimum allowable base salary of €500. This generation evolved in circumstances leading to the Greek debt crisis and participated in the 2010–2011 Greek protests.[94]

- In Spain, they are referred to as the mileuristas (for €1,000, "the thousand-euro-ists").[95]

- In Portugal, they are called the Geração à Rasca (the "Scraping-By Generation"); a twist on the older term Geração Rasca ("the Lousy Generation") used by detractors to refer to student demonstrations in the 1990s against Education Ministers António Couto dos Santos and later Manuela Ferreira Leite.

- In France, they are called Génération précaire ("The Precarious Generation").

- In Italy the term "generation of 1,000 euros" is used.

- Xennials, Oregon Trail Generation, and Generation Catalano are terms used to describe individuals born during Generation X/Millennial cusp years. Xennials is a portmanteau blending the words Generation X and Millennials to describe a microgeneration of people born from the late 1970s to the early 1980s.[96][97][98][99][100]

- Zillennials, Zennials, Snapchat Generation, and MinionZ are terms used to describe individuals born during the Millennial/Generation Z cusp years. Zillennials is a portmanteau blending the words Millennials and Generation Z to describe a microgeneration of people born from the early 1990s to the early 2000s.[101]

Criticism

[edit]Philip N. Cohen, a sociology professor at the University of Maryland, criticized the use of "generation labels", stating that the labels are "imposed by survey researchers, journalists or marketing firms" and "drive people toward stereotyping and rash character judgment." Cohen's open letter to the Pew Research Center, which outlines his criticism of generational labels, received at least 150 signatures from other demographers and social scientists.[102]

Louis Menand, writer at The New Yorker, stated that "there is no empirical basis" for the contention "that differences within a generation are smaller than differences between generations." He argued that generational theories "seem to require" that people born at the tail end of one generation and people born at the beginning of another (e.g. a person born in 1965, the first year of Generation X, and a person born in 1964, the last of the Boomer era) "must have different values, tastes, and life experiences" or that people born in the first and last birth years of a generation (e.g. a person born in 1980, the last year of Generation X, and a person born in 1965, the first year of Generation X) "have more in common" than with people born a couple years before or after them.[19]

In 2023, after a review of their research and methods, and consulting with external experts, Pew Research Center announced a change in their use of generation labels to "avoid reinforcing harmful stereotypes or oversimplifying people’s complex lived experiences", and said that, going forward, they will only conduct generational analysis when historical data is available that allows them to "compare generations at similar stage of life" and "won’t always default to using the standard generational definitions and labels."[103]

See also

[edit]- Age set

- Cusper

- Generation time

- Generational accounting

- Generationism

- Intergenerational equity

- Intergenerationality

- Transgenerational design

References

[edit]- ^ "Definition of Generation". Oxford Advanced Learners' Dictionary.

- ^ "Generational Insights and the Speed of Change". American Marketing Association. 30 June 2022. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ a b c Pilcher, Jane (September 1994). "Mannheim's Sociology of Generations: An undervalued legacy" (PDF). British Journal of Sociology. 45 (3): 481–495. doi:10.2307/591659. JSTOR 591659. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ "Generate | Define Generate at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. 15 June 1995. Archived from the original on 11 October 2010. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ "Definition of generation | Dictionary.com". www.dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ "Generation". Miriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ a b Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Social Policy Division [1] Archived 2 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine SF2.3: Mean age of mothers at first childbirth. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ Bedasso, Biniam Egu (March 2008). "Investing in education as a means and as an end: exploring the microfoundations of the MDGs" (PDF). United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 June 2012. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ Mathews TJ, Hamilton BE. [2] Archived 25 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine Delayed childbearing: More women are having their first child later in life. NCHS data brief, no 21. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2009. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ^ Whiteman, S. D.; McHale, S. M.; Soli, A. (2011). "Theoretical Perspectives on Sibling Relationships". Journal of Family Theory & Review. 3 (2): 124–139. doi:10.1111/j.1756-2589.2011.00087.x. PMC 3127252. PMID 21731581.

- ^ Mannheim, k (1952). Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge. London: RKP.

- ^ a b Biggs, Simon (2007). "Thinking about generations: Conceptual positions and policy implications". Journal of Social Issues. 63 (4): 695–711. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00531.x.

- ^ a b c d e Wohl, Robert (1979). The generation of 1914. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 203–209. ISBN 9780674344662. Archived from the original on 18 June 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "Hans Jaeger. Generations in History: Reflections on a Controversy. Translation of "Generationen in der Geschichte: Überlegungen zu einer umstrittenen Konzeption," originally published in Geschichte und Gesellschaft 3 (1977), 429–452. p 275" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 November 2010. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ Gilleard, Chris; Higgs, Paul (2002). "The third age: Class, cohort or generation?". Ageing and Society. 22 (3): 369–382. doi:10.1017/s0144686x0200870x. S2CID 145549764.

- ^ Mannheim, Karl (1928). "Das Problem der Generationen". Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie. 7 (2–3): 180.

- ^ An English translation of his 1928 article came out as Karl Mannheim, "The Problem of Generations", in: Kecskemeti, Paul (ed.) Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge: Collected Works. Vol. 5. New York: Routledge. Quoted on pp. 297-298.

- ^ a b Hoover, Eric (11 October 2009). "The Millennial Muddle". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ a b Menand, Louis (11 October 2021). "It's Time to Stop Talking About "Generations"". The New Yorker. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Brooks, David (5 November 2000). "What's the Matter With Kids Today? Not a Thing". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 January 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ^ Lind, Michael (26 January 1997). "Generation Gaps". The New York Times Book Review. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ^ Giancola, Frank (1 December 2006). "The Generation Gap: More Myth Than Reality". Human Resource Planning. Archived from the original on 5 July 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ Jaeger, Hans (1985). "Generations in History: Reflections on a Controversial Concept" (PDF). History and Theory. 24 (3): 273–292. doi:10.2307/2505170. JSTOR 2505170. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Strauss, William; Howe, Neil (1991). Generations: The History of America's Future, 1584–2069. New York: Harper.

- ^ Jaeger, Hans (1885). "Generations in History: Reflections on a Controversial Concept" (PDF). History and Theory. 24 (3): 283. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Mannheim, Karl (1952). "The Problem of Generations". In Kecskemeti, Paul (ed.). Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge: Collected Works, Volume 5. New York: Routledge. pp. 276–322.

- ^ Hart-Brinson, Peter (2018). The Gay Marriage Generation: How the LGBTQ Movement Transformed American Culture. New York: NYU Press.

- ^ Taylor, Paul; Keeter, Scott, eds. (24 February 2010). "The Millennials. Confident, Connected. Open to Change". p. 5. Archived from the original on 27 February 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- ^ Dan Woodman, Johanna Wyn (2015). Youth and Generation. Sage. p. 164. ISBN 9781446259047.

- ^ Woodman, Dan; Wyn, Johanna (2015). Youth and Generation Rethinking Change and Inequity in the Lives of Young People. London: Sage Publications Ltd. p. 122. ISBN 9781446259047.

- ^ Grenier, Amanda (2007). "Crossing age and generational boundaries: Exploring intergenerational research encounters". Journal of Social Issues. 63 (4): 713–727. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00532.x.

- ^ Ryder, Norman (1965). "The cohort as a concept in the study of social change". American Sociological Review. 30 (6): 843–861. doi:10.2307/2090964. JSTOR 2090964. PMID 5846306.

- ^ Grenier, Amanda (2007). "Crossing age and generational boundaries: Exploring intergenerational research encounters". Journal of Social Issues. 63 (4): 718. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00532.x.

- ^ Mannheim, Karl. (1952) 'The problem of generations', in K. Mannheim, Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge, London: RKP

- ^ Chaney, Damien; Touzani, Mourad; Ben Slimane, Karim (2017). "Marketing to the (new) generations: summary and perspectives". Journal of Strategic Marketing. 25 (3): 179. doi:10.1080/0965254X.2017.1291173.

- ^ Jaeger, Hans (1985). "Generations in History: Reflections on a Controversial Concept". History and Theory. 24 (3): 273–292. doi:10.2307/2505170. JSTOR 2505170. S2CID 3680078.

- ^ Wohl, Robert (1979). The generation of 1914. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674344662. Archived from the original on 18 June 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ Howe, Neil; Strauss, William (1991). Generations: The History of Americas Future. 1584 to 2069. New York: William Morrow and Company. pp. 247–260. ISBN 0688119123.

- ^ Safire, William (28 November 2008). "Generation What?". The New York Times Magazine. Archived from the original on 6 January 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "The Generation Gap in American Politics" (PDF). Pew Research Center. March 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ Hunt, Tristram (6 June 2004). "One last time they gather, the Greatest Generation". The Observer. London. Archived from the original on 13 July 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2009.

- ^ "Generations and Age". Pew Research. 1 March 2018. Archived from the original on 28 May 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- ^ "Definitions - Pew Research Center". www.pewresearch.org. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- ^ See:

- Brandon, Emily. "The Youngest Baby Boomers Turn 50". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- "Baby Boomers". History.com. Archived from the original on 17 December 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- Fry, Richard. "This year, Millennials will overtake Baby Boomers". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on 10 November 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- Howe, Neil; Strauss, William (1991). Generations: The History of Americas Future, 1584 to 2069. New York: William Morrow. pp. 299–316. ISBN 9780688119126.

- Owram, Doug (1997). Born at the Right Time. Toronto: Univ Of Toronto Press. p. xiv. ISBN 9780802080868.

- Jones, Landon (1970). Great Expectations: America and the Baby Boom Generation. New York: Coward, McCann and Geoghegan.

- ^ "National Population Projections". census.gov. 31 July 1997. Archived from the original on 31 July 1997. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ Boylan, Jennifer Finney (23 June 2020). "Opinion | Mr. Jones and Me: Younger Baby Boomers Swing Left". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 December 2020. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ "Vol. 33, No. 1: Generations". WSJ. The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 29 June 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ Jackson Ii, Ronald L.; Hogg, Michael A. (29 June 2010). Encyclopedia of Identity. ISBN 9781412951531.

- ^ Horovitz, Bruce (4 May 2012). "After Gen X, Millennials, what should next generation be?". USA Today. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ Grazziotin-Soares, R.; Ardenghi, D. M. (2022). "Drawings to explore faculties' and students' perceptions from different generations cohorts about dental education: A pilot study". BDJ Open. 8 (1): 17. doi:10.1038/s41405-022-00109-5. PMC 9199317. PMID 35705540.

- ^ a b Burclaff, Natalie. "Research Guides: Doing Consumer Research: A Resource Guide: Generations". guides.loc.gov. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (27 April 2022). "A generational portrait of Canada's aging population from the 2021 Census". statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ "Millennials cheer New Zealand lawmaker's 'OK, Boomer' remark". Reuters. 6 November 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ a b "2019 Data Show Baby Boomers Nearly 9 Times Wealthier Than Millennials". Census.gov. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ^ Fry, Richard (28 April 2020). "Millennials overtake Baby Boomers as America's largest generation". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on 28 April 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ Dimock, Michael (17 January 2019). "Defining generations: Where Millennials end and Generation Z begins". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- ^ Fell, Ashley. "The substantial impact COVID-19 has had on Gen Z". McCrindle. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Farrel, Christopher A. (19 March 2024). "What Is Generation Alpha? Meaning, Characteristics, and Future". Investopedia. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Williams, Alex (19 September 2015). "Meet Alpha: The Next 'Next Generation'". Fashion. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ "Welcome Gen Beta". mccrindle.com.au. 19 December 2024. Retrieved 1 January 2025.

- ^ Cross, Greta (31 December 2024). "Welcome Gen Beta: A new generation of humanity starts in 2025". USA Today. Retrieved 1 January 2025.

- ^ "Baby boom and immigration prop up Czech population". Aktuálně.cz (in Czech). 20 September 2007. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Yan, Yunxiang (2006). "Little Emperors or Frail Pragmatists? China's '80ers Generation". Current History. 105 (692): 255–262. doi:10.1525/curh.2006.105.692.255.

- ^ "Post-90s Graduates Changing the Workplace".

- ^ "Brands Struggle To Connect With China's 'Post-90s' Generation". Jing Daily. 2 July 2012.

- ^ Lee, Coleen (15 January 2010). "Post 80s rebels with a cause". The Standard. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ Kwong wing-yuen (ed.), Zhan zai dan de yi bian, Xianggang bashihou, Hong Kong, UP Publications Limited, 2010, pp. 16–32.

- ^ Michelle Sawyer, Women’s Reproductive Rights under State Socialism In Hungary: The Ratkó Era, 1950-1956, Central European University, 2010

- ^ Erzsébet Földházi, Structure and Future of Hungary’s Population, in Monostori, J. - Őri, P. - Spéder, Zs. (eds.) Demographic Portrait of Hungary (HDRI, Budapest: 2015), 211–224

- ^ "Generational Differences Between India and the U.S". Blogs.harvardbusiness.org. 28 February 2009. Archived from the original on 25 December 2009. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ "New Israeli Study Finds Signs of Trauma in Grandchildren of Holocaust Survivors". Haaretz. 16 April 2012. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ "Dessertgenerasjon". 25 November 2022.

- ^ Tsvetkova G.A. Richly, beautifully, happily: the cultural strategies of everyday live "Generation Winners // Educational sciences – 2013 №6. ISSN 2072-2524 [3] Archived 18 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Miroshkina M.R. "Interpretations of the Generations Theory in the Context of Russian Education" // Yaroslavl Pedagogical Herald, 2017, №6 [4] Archived 18 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "$270 million in Medisave top-ups for eligible Pioneer Generation and Merdeka Generation seniors in July". The Straits Times. 13 June 2019. Archived from the original on 3 November 2019. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ Smith, David (8 May 2014). "South Africans vote in first election for 'born free' generation". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ Malefane, Sipho (31 December 2019). "# Ama2000 – Generation Z". Sipho's reflexions. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ "Summer Yama 2000 #RefreshWherevs". YouTube. Archived from the original on 21 April 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ "Fiasco of 386 Generation". The Korea Times. Archived from the original on 28 March 2010. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ a b "Shinsedae: Conservative Attitudes of a 'New Generation' in South Korea and the Impact on the Korean Presidential Election". Eastwestcenter.org. Archived from the original on 15 September 2010. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ "Social cohesion Ideological differences divide generations". The Korea Herald. 26 August 2009. Archived from the original on 5 February 2010.

- ^ Jip, Choi Jang (15 May 2019). "Democratization, Civil Society, and the Civil Social Movement in Korea". Korea Journal. 40 (3): 26–57. ISSN 1225-4576. Retrieved 23 August 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Sun Young, Park. "Shinsedae: Conservative Attitudes of a 'New Generation' in South Korea and the Impact on the Korean Presidential Election". East-West Centre. Hankook Ilbo. Archived from the original on 15 September 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ^ Caballero, Manuela; Baigorri, Artemio (2019). "Glocalising the theory of generations: The case of Spain". Time & Society. 28 (1): 333–357. doi:10.1177/0961463X18783374.

- ^ Track the History Timeline on the Australian Human Rights

- ^ "The Beat Generation". Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ Jensen, J.B. (2007). Future consumer tendencies and shopping behaviour: The development up until 2015-17. Research paper No. 1. Denmark: Marianne Levinsen & Jesper Bo Jensen. pp. 13–17. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013.Seigle, Greg (6 April 2000). "Some Call It 'Jones'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

- ^ "Press Release: Generation Jones is driving NZ Voter Volatility". Scoop Independent News (NZ). 13 September 2005. Archived from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

- ^ Wastell, David (15 October 2000). "Generation Jones comes of age in time for election". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 7 March 2007. Retrieved 12 June 2009.

- ^ "The MetLife Study of Gen X: The MTV Generation Moves into Mid-Life" (PDF). MetLife. April 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ Raphelson, Samantha (6 October 2014). "From GIs To Gen Z (Or Is It iGen?): How Generations Get Nicknames". NPR. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ "MTV: Rewinding 20 years of music revolution". CNN. 1 August 2001. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Itano, Nicole (14 May 2009). "In Greece, education isn't the answer". Global Post. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ^ "Γενιά των 600 € και "αγανακτισμένοι" της Μαδρίτης - βίοι παράλληλοι; - Πολιτική". DW.COM. 30 May 2011. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ Pérez-Lanzac, Carmen (12 March 2012). "1,000 euros a month? Dream on…". El Pais. Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ^ Miller, Ryan. "Are you a Xennial? How to tell if you're the microgeneration between Gen X and Millennial". Archived from the original on 1 August 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ Anna, Garvey (25 May 2016). "The Biggest Difference Between Millennials and My Generation". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 25 September 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ D'Souza, Joy (28 June 2017). "Xennials, The Microgeneration Between Gen X And Millennials". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ^ Shafrir, Doree (24 October 2011). "Generation Catalano". Slate. The Slate Group. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ "If You Don't Fit In With Gen X or Millennials You Might Be A Xennial"Ok Boomer"". HuffPost Canada. 28 June 2017. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ Hannah L. Ubl; Lisa X. Walden; Debra Arbit (24 April 2017). "Chapter 13: Making Adjustments for Ages and Life Stages". Managing Millennials For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 266. ISBN 978-1-119-31022-8.

- ^ Cohen, Philip N. (7 July 2021). "Opinion | Generation labels mean nothing. It's time to retire them". Washington Post. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ^ Parker, Kim (22 May 2023). "How Pew Research Center will report on generations moving forward". Pew Research Center.

Further reading

[edit]- Fry, Richard (16 January 2015). "This Year, Millennials Will Overtake Baby Boomers". Pew Center.

- Ialenti, Vincent (6 April 2016). "Generation". Society for Cultural Anthropology. Archived from the original on 13 December 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- Ulrike Jureit: "Generation, Generationality, Generational Research", version: 2, in: Docupedia Zeitgeschichte, 09. August 2017

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of generation at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of generation at Wiktionary Quotations related to Generation at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Generation at Wikiquote Media related to Generations at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Generations at Wikimedia Commons