Gay liberation

| Gay liberation | |

|---|---|

| Part of LGBT movements and the sexual revolution | |

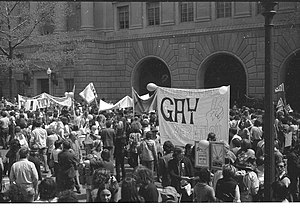

Gay liberation demonstration in 1970 | |

| Date | 1969 – c. 1980 |

| Location | United States, Canada, Europe, Australia and other areas |

| Caused by | Sexual revolution, Homophobia |

| Goals | Increasing legal rights for LGBT people Increasing acceptance of LGBT people Countering internalized homophobia |

| Methods | Civil resistance Coming out Consciousness raising Direct action |

| Resulted in | Success in many of the goals Legalized same-sex marriage and other LGBT rights in some jurisdictions Continuing widespread homophobia |

| Part of a series on |

| LGBTQ topics |

|---|

|

|

The gay liberation movement was a social and political movement of the late 1960s through the mid-1980s[a] in the Western world, that urged lesbians and gay men to engage in radical direct action, and to counter societal shame with gay pride.[5] In the feminist spirit of the personal being political, the most basic form of activism was an emphasis on coming out to family, friends, and colleagues, and living life as an openly lesbian or gay person.[5]

The Stonewall Inn in the gay village of Greenwich Village, Manhattan, New York City, was the site of the June 1969 Stonewall riots, and became the cradle of the modern LGBT rights movement, and the subsequent gay liberation movement.[6][7][8] Early in the seventies, annual political marches through major cities, (usually held in June, originally to commemorate the yearly anniversary of the events at Stonewall) were still known as "Gay Liberation" marches. Not until later in the seventies (in urban gay centers) and well into the eighties (in smaller communities) did the marches begin to be called "gay pride parades".[5] The movement involved the lesbian and gay communities in North America, South America, Western Europe, Australia and New Zealand.

Gay liberation is also known for its links to the counterculture of the time (e.g. groups like the Radical Faeries) and for some gay liberationists' intent to transform or abolish fundamental institutions of society such as gender and the nuclear family,[5] regardless of whether they had anything to do with the actual principles of gay rights.[9] For some offsets of movement, the politics were radical, anti-racist, and anti-capitalist.[10] In order to achieve such goals, consciousness raising and direct action were employed. While HIV/AIDS activism and awareness (in groups such as ACT UP) radicalized a new wave of lesbians and gay men in the 1980s, and radical groups have continued to exist ever since, by the early 1990s the radicalism of gay liberation was eclipsed in the mainstream by newly-out, pro-assimilationist gay men and women who stressed civil rights and mainstream politics.[11]

The term gay liberation sometimes refers to the broader movement to end social and legal oppression against LGBT people.[12][13] Sometimes the term gay liberation movement is even used synonymously or interchangeably with the gay rights movement.[14] The Christopher Street Liberation Day Committee was formed in New York City to commemorate the first anniversary of the June 1969 Stonewall riots, the beginning of the international tradition of a late-June event to celebrate gay pride.[15] The annual gay pride festivals in Berlin, Cologne, and other German cities are known as Christopher Street Days or "CSD"s.

Origins and history of movement

[edit]Although the Stonewall riots of 1969 in New York City are popularly remembered as the spark that produced a new movement, the origins predate these iconic events.[16] Resistance to police bar-raids was nothing new: as early as 1725, customers fought off a police raid at a London homosexual molly house.[17]

Organized movements, particularly in Western Europe, have been active since the 19th century, producing publications, forming social groups and campaigning for social and legal reform. In the early 1890s, the trial of Oscar Wilde was widely reported in Germany and spurred discussion of homosexuality, leading to the homosexual emancipation movement in Germany, the first modern gay rights movement.[18][19]

The movements of the period immediately preceding gay liberation, from the end of World War II to the late 1960s, are known collectively as the homophile movement.[20] The homophile movement has been described as "politically conservative", although its calls for social acceptance of same-sex love were seen as radical fringe views by the dominant culture of the time.

Name

[edit]While the movement always included all LGBT people, in those days the unifying term was "gay", and later, "lesbian and gay", much as in the late eighties and early nineties, "queer" was reclaimed as a one-word alternative to the ever-lengthening string of initials, especially when used by radical political groups.[11] Specifically, the word 'gay' was preferred to previous designations, such as homosexual or homophile, that were still in use by mainstream news outlets, when they would carry news about gay people at all. The New York Times refused to use the word 'gay' until 1987, up to that time insisting on 'homosexual'.[21]

1960s

[edit]The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (June 2018) |

Early 1960s New York City, under the Wagner mayoral administration, was beset with harassment against the gay community, particularly by the New York City Police Department. Homosexuals were among the targets of a drive to rid the city of undesirables. Consequently, only the Mafia had the power and financial resources to run gay bars and clubs. By 1965, influenced by Frank Kameny's addresses in the early 1960s, Dick Leitsch, the president of the New York Mattachine Society, advocated direct action, and the group staged the first public homosexual demonstrations and picket lines in the 1960s.[22] Kameny, founder of Mattachine Washington in 1961, had advocated militant action reminiscent of the black civil rights campaign, while also arguing for the morality of homosexuality.

The New York State Liquor Authority (SLA) did not allow homosexuals to be served in licensed bars in the state under penalty of revocation of the bar's license to operate. This denial of public accommodation had been confirmed by a court decision in the early 1940s. A legal study on the city's alcoholic beverage law commissioned by Mattachine New York concluded there was no law per se prohibiting homosexuals gathering in bars; however, laws did prohibit disorderly conduct — which the SLA had been interpreting as homosexual behavior — in bars. Leitsch informed the press that three members of Mattachine New York would turn up at a restaurant on the Lower East Side, announce their homosexuality and, upon the refusal of service, make a complaint to the SLA. This came to be known as the "Sip-In" and only succeeded at the third attempt[clarification needed] at Julius in Greenwich Village. The "Sip-In", though, did gain extensive media attention and the resultant legal action against the SLA eventually prevented the agency from revoking licenses on the basis of homosexual solicitation in 1967.

At the beginning of gay rights protest, news on Cuban prison work camps for homosexuals inspired the Mattachine Society to organize protests at the United Nations and the White House, in 1965.[23][24]

In the years before 1969, the organization also was effective in getting New York City to change its policy of police entrapment of gay men, and to rescind its hiring practices designed to screen out gay people.[25] However, the significance of the new John Lindsay administration and the use of the media by Mattachine New York should not be underestimated in ending police entrapment. Lindsay would later gain a reputation for placing much focus on quelling social troubles in the city and his mayorship coinciding with the end of entrapment should be seen as significant. By late 1967, a New York group called the Homophile Youth Movement in Neighborhoods (HYMN), essentially a one-man operation on the part of Craig Rodwell, was already espousing the slogans "Gay Power" and "Gay is Good" in its publication HYMNAL.

The 1960s was a time of social upheaval in the West, and the sexual revolution and counterculture influenced changes in the homosexual subculture, which in the U.S. included bookshops, publicly sold newspapers and magazines, and a community center. It was during this time that Los Angeles saw its first big gay movement. In 1967, the night of New Years, several plainclothes police officers infiltrated the Black Cat Tavern.[26] After arresting several patrons for kissing to celebrate the occasion,[27] the officers began beating several patrons[28] and ultimately arrested 16 more bar attendees including three bartenders.[28] This created a riot in the immediate area, ultimately bringing about a more civil demonstration of over 200 attendees several days later protesting the raids.[29] The protest was met by squadrons of armed policemen.[26] It was from this event that the publication The Advocate and organization Metropolitan Community Church (led by Pastor Troy Perry) were born.[30]

Few areas in the U.S. saw a more diverse mix of subcultures than Greenwich Village, which was host to the gay street youth. A group of young, effeminate runaways, shunned by their families, society, and the gay community, they reflected the countercultural movement more than any other homosexual group. Refusing to hide their homosexuality, they were brutalized, rebellious tearaways who took drugs, fought, shoplifted and hustled older gay men in order to survive. Their age, behavior, feminine attire and conduct left them isolated from the rest of the gay scene, but living close to the streets, they made the perfect warriors for the imminent Stonewall Riots. These emerging social possibilities, combined with the new social movements such as Black Power, women's liberation, and the student insurrection of May 1968 in France, heralded a new era of radicalism. After the Stonewall riots in New York City in late June 1969, many within the emerging gay liberation movement in the U.S. saw themselves as connected with the New Left rather than the established homophile groups of the time. The words "gay liberation" echoed "women's liberation"; the Gay Liberation Front consciously took its name from the National Liberation Fronts of Vietnam and Algeria; and the slogan "Gay Power", as a defiant answer to the rights-oriented homophile movement, was inspired by Black Power, which was a response to the civil rights movement.[31]

Vanguard 1965–1967

[edit]Vanguard was a gay rights youth organization active from 1965 into 1967 in San Francisco. It was founded by Adrian Ravarour and Billy Garrison, and Vanguard magazine was founded by Jean-Paul Marat and Keith St.Clare. Ravarour had been asked by Joel Williams to help the Tenderloin LGBT youth who suffered discrimination.[32] Seeing their conditions, Ravarour, a priest, led Vanguard for ten months and taught gay rights, then led Vanguard members in early demonstrations for equal rights. After he resigned in May 1966, J. P. Marat joined Vanguard and led it in six months of protests. Glide Church began to sponsor it in June 1966 assisting Vanguard to apply to become a non-profit and apply for the EOC grant. The organization dissolved due to internal clashes in late 1966 and early 1967. Former members reorganized as The Gay and Lesbian Center and Glide re-directed the EOC funds intended for Vanguard to form a service agency and new non-profit The Hospitality House.[33]

1969

[edit]On March 28, 1969, in San Francisco, Leo Laurence (the editor of Vector, magazine of the United States' largest homophile organization, the Society for Individual Rights) called for "the Homosexual Revolution of 1969", exhorting gay men and lesbians to join the Black Panthers and other left-wing groups and to "come out" en masse. Laurence was expelled from the organization in May for characterizing members as "timid" and "middle-class, uptight, bitchy old queens".

Laurence then co-founded a militant group the Committee for Homosexual Freedom with Gale Whittington, Mother Boats, Morris Kight and others. Whittington had been fired from States Steamship Company for being openly gay, after a photo of him by Mother Boats appeared in the Berkley Barb, next to the headline "HOMOS, DON'T HIDE IT!", the revolutionary article by Leo Laurence. The same month Carl Wittman, a member of CHF began writing Refugees from Amerika: A Gay Manifesto, which would later be described as "the bible of Gay Liberation". It was first published in the San Francisco Free Press and distributed nationwide, all the way to New York City, as was the Berkeley Barb with Laurence's stories on CHF's gay guerrilla militant initiatives and Mother Boats' photographs.

CHF was soon renamed the Gay Liberation Front (GLF); the Gay Liberation Front was a loose network of organizations throughout the US and abroad that determined their own political goals and modes of organization.[34] One GLF statement of purpose explained their revolutionary ambitions:[35]

We are a revolutionary group of men and women formed with the realization that complete sexual liberation for all people cannot come about unless existing social institutions are abolished. We reject society's attempt to impose sexual roles and definitions of our nature.

Gay Liberation Front activist Martha Shelley wrote, "We are women and men who, from the time of our earliest memories, have been in revolt against the sex-role structure and nuclear family structure."[36]

In December 1969 the Gay Liberation Front made a cash donation to the Black Panthers, some of whose leaders had expressed homophobic sentiments.[citation needed] Prominent GLF members were also strong supporters of Fidel Castro's regime. These actions cost GLF, a numerically small group, popular support in New York City, and some of its members left to form the Gay Activists' Alliance.[25] The GLF virtually disappeared from the New York City political scene after the first Stonewall commemoration parade in 1970.[citation needed]

Mark Segal, a member of GLF from 1969 to 1971, continued[when?] to push gay rights in various venues. As a pioneer of the local gay press movement, he was one of the founders and former president of both the National Gay Press Association and the National Gay Newspaper Guild.[citation needed] He also is the founder and publisher of the award-winning Philadelphia Gay News which recently[when?] celebrated its 30th anniversary.[citation needed] In 1973 Segal disrupted the CBS evening news with Walter Cronkite, an event covered in newspapers across the country and viewed by 60% of American households, many seeing or hearing about homosexuality for the first time.[citation needed] Before the networks agreed to put a stop to censorship and bias in the news division, Segal went on to disrupt The Tonight Show starring Johnny Carson, and Barbara Walters on the Today show. The trade newspaper Variety claimed that Segal had cost the industry $750,000 in production, tape delays, and lost advertising revenue. Aside from publishing, Segal has also reported on gay life from far reaching places as Lebanon, Cuba, and East Berlin during the fall of the Berlin Wall. He and Bob Ross, former publisher of San Francisco's Bay Area Reporter represented the gay press and lectured in Moscow and St. Petersburg at Russia's first openly gay conference, referred to as Russia's Stonewall.[citation needed] He recently coordinated a network of local gay publications nationally to celebrate October as gay history month,[citation needed] with a combined print run reaching over a half million people.[citation needed] His determination to gain acceptance and respect for the gay press can be summed up by his 15-year battle to gain membership in the Pennsylvania Newspaper Association one of the nation's oldest and most respected organizations for daily and weekly newspapers. The battle ended after The Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia Daily News and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette joined forces and called for PGN's membership. In 2005, he produced Philadelphia's official July 4 concert for a crowd estimated at 500,000 people. The show featured Sir Elton John, Patti LaBelle, Bryan Adams, and Rufus Wainwright. On a recent anniversary of PGN, an editorial in The Philadelphia Inquirer stated: "Segal and PGN continue to step up admirably to the challenge set for newspapers by H.L. Mencken: to afflict the comfortable and to comfort the afflicted."[citation needed]

1970s

[edit]

By the summer of 1970, groups in at least eight American cities were sufficiently organized to schedule simultaneous events commemorating the Stonewall riots for the last Sunday in June. The events varied from a highly political march of three to five thousand in New York and thousands more at parades in Los Angeles, San Francisco and Chicago. While groups using the Gay Liberation Front name appeared around the U.S., in New York that organization was replaced totally by the Gay Activist Alliance. Groups with a "Gay Lib" approach began to spring up around the world, such as Campaign Against Moral Persecution (CAMP, Inc.), and Gay Liberation Front groups in Australia, Canada, the US and the UK. The lesbian group Lavender Menace was also formed in the U.S. in response to both the male domination of other Gay Liberation groups and the anti-lesbian sentiment in the Women's Movement. Lesbianism was advocated as a feminist choice for women, and the first currents of lesbian separatism began to emerge.[citation needed]

In August of the same year, Huey Newton, the leader of the Black Panthers, publicly expressed his support for gay liberation in his letter titled "A Letter from Huey to the Revolutionary Brothers and Sisters About the Women's Liberation and Gay Liberation Movements" [37] stating that:[37]

Whatever your personal opinions and your insecurities about homosexuality and the various liberation movements among homosexuals and women (and I speak of the homosexuals and women as oppressed groups), we should try to unite with them in a revolutionary fashion.

...

Some people say that [homosexuality] is the decadence of capitalism. I don't know if that is the case; I rather doubt it. But whatever the case is, we know that homosexuality is a fact that exists, and we must understand it in its purest form: that is, a person should have the freedom to use his body in whatever way he wants.

This statement by Newton was revolutionary. There has been another black civil rights organization that saw gay and lesbians as another oppressed group in the United States during this decade.[38] Newton recognized the same challenges that both oppressed groups face. He writes in his letter:

We haven't said much about the homo- sexual at all but we must relate to the homosexual movement because it's a real thing. I know through reading, and through my life experience, my observations, that homosexuals are not given freedom and liberty by anyone in the society. Maybe they might be the most oppressed people in the society.[38]

Furthermore, Newton called for the removal of derogatory terms in the Black Panther's vocabulary.[38] This helped advance the Gay Liberation Movement and legitimized it even further.

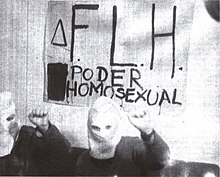

Although a short-lived group, the Comite Pederastique de la Sorbonne, had meetings during the student uprising of May 1968, the real public debut of the modern gay liberation movement in France occurred on 10 March 1971, when a group of lesbians from the Front homosexuel d'action révolutionnaire (FHAR) disrupted a live radio broadcast entitled: "Homosexuality, This Painful Problem".[39] The expert guests, including Ira C. Kleinberg, Herman Kleinstein, a Catholic priest, and a dwarf, were suddenly interrupted by a group of lesbians from the audience, yelling, "It's not true, we're not suffering! Down with the heterocops!" The protesters stormed the stage, one young woman taking hold of the priest's head and pounding it repeatedly against the table. The control room quickly cut off the microphones and switched to recorded music.[39] Later on the 15th of May the first specifically Gay Power march takes place in Europe in Örebro, Sweden, led by a group known as Gay Power Club.[40]

In 1971, Dennis Altman published Homosexual: Oppression and Liberation, considered an important intellectual contribution to the ideas that shaped gay liberation movements in the English-speaking world. Among his ideas were "the polymorphous whole"[41]: 58–95 and his posing of the notion of "the end of the homosexual",[41]: 216–228 in which the potential for both heterosexual and homosexual behaviour becomes a widespread cultural and psychological phenomenon.[42]: 116 Similarly, Allen Young's 1972 manifesto "Out of the Closet, into the Streets" envisions gay liberation as the recognition of humanity's innate bisexuality and androgyny within relationships that are free, expressive, and equal. Young portrays lesbians and gay men as the vanguard of sexual and human liberation.[42]: 118 Sociologist Steven Seidman interprets these intellectual productions as precursors to queer theory.[42]

See also

[edit]- Decriminalization of homosexuality

- Gay Lib v. University of Missouri

- Gay Community News (Boston)

- List of fictional gay characters

- Radical Faeries

Explanatory notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Rapp, Linda (2003). "Symbols" (PDF). glbtq.com. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- ^ "1969, The Year of Gay Liberation". The New York Public Library. June 2009. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- ^ Hoffman, 2007.

- ^ Phoenix (29 June 2012). "Gay Rights Are Not Queer Liberation". autostraddle.com. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d Hoffman, 2007, pp.xi-xiii.

- ^ Julia Goicichea (August 16, 2017). "Why New York City Is a Major Destination for LGBT Travelers". The Culture Trip. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ Eli Rosenberg (June 24, 2016). "Stonewall Inn Named National Monument, a First for the Gay Rights Movement". The New York Times. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ "Workforce Diversity The Stonewall Inn, National Historic Landmark National Register Number: 99000562". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ Bernadicou, August (2 October 2023). "Come Out!". The LGBTQ History Project.

- ^ "Gay Liberation Front: Manifesto. London". 1978 [1971].

- ^ a b Hoffman, 2007, pp. 79–81.

- ^ "the definition of gay liberation". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2016-07-03.

- ^ "gay liberation Definition in the Cambridge English Dictionary". dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved 2016-07-03.

- ^ "gay rights movement | political and social movement". Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ Stryker, Susan. "Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day: 1970". PlanetOut. Archived from the original on 31 March 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Armstrong, Elizabeth A.; Crage, Suzanna M. (2006). "Movements and Memory: The Making of the Stonewall Myth". American Sociological Review. 71 (5): 724–751. doi:10.1177/000312240607100502. JSTOR 25472425. S2CID 144545934.

- ^ Norton, Rictor (1992). Mother Clap's Molly House: The Gay Subculture in England, 1700–1830. GMP. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-85449-188-9.

- ^ Whisnant, Clayton J. (2016). Queer Identities and Politics in Germany: A History, 1880–1945. Columbia University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-939594-10-5.

- ^ Dickinson, Edward Ross (2014). Sex, Freedom, and Power in Imperial Germany, 1880–1914. Cambridge University Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-107-04071-7.

- ^ "The Persistence of Transnational Organizing: The Case of the Homophile Movement". Archived from the original on 2019-09-27. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ^ Hoffman, 2007, p. 78.

- ^ Thomas Mallon Archived 2009-08-18 at the Wayback Machine "They Were Always in My Attic," American Heritage, February/March 2007.

- ^ "Fidel Castro's Horrific Record on Gay Rights". The Daily Beast. 27 November 2016.

- ^ Marc Stein (2012). Rethinking the Gay and Lesbian Movement. Routledge. ISBN 9780415874106.

- ^ a b Carter, David, 2004. Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution.

- ^ a b "Speaking Out". johnrechy.com.

- ^ "Timeline of Homosexual History, 1961 to 1979". tangentgroup.org. Archived from the original on 2014-05-11.

- ^ a b "The Tangent Group: Press Release regarding the 1966 raid on the Black Cat bar". tangentgroup.org. Archived from the original on 2015-04-27.

- ^ L.A., 1/1/67: the Black Cat riots. | The Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide (March, 2006)

- ^ Letters from Camp Rehoboth – September 14, 2007 – PAST Out Archived May 18, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bernadicou, August. "Martha Shelley". August Nation. The LGBTQ History Project. Archived from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ Bernadicou, August. "Adrian Ravarour". August Nation. The LGBTQ History Project. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- ^ "Home". Vanguard 1965. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ "come out!" (PDF). OutHistory. June 1970.

- ^ "Gay Liberation Front". glbtq, an encyclopedia of gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender and queer culture. glbtq.com. Archived from the original on 22 February 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

GLF's statement of purpose clearly stated its revolutionary goals: 'We are a revolutionary group of men and women formed with the realization that complete sexual liberation for all people cannot come about unless existing social institutions are abolished. We reject society's attempt to impose sexual roles and definitions of our nature.'

- ^ Shelley, Martha, 1970. Gay is Good.

- ^ a b Newton, Huey. "Huey P. Newton on gay, women's liberation". Workers World. workers.org. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

Whatever your personal opinions and your insecurities about homosexuality and the various liberation movements among homosexuals and women (and I speak of the homosexuals and women as oppressed groups), we should try to unite with them in a revolutionary fashion. ... I know through reading, and through my life experience and observations that homosexuals are not given freedom and liberty by anyone in the society. They might be the most oppressed people in the society. And what made them homosexual? Perhaps it's a phenomenon that I don't understand entirely. Some people say that it is the decadence of capitalism. I don't know if that is the case; I rather doubt it. But whatever the case is, we know that homosexuality is a fact that exists, and we must understand it in its purest form: that is, a person should have the freedom to use his body in whatever way he wants. That is not endorsing things in homosexuality that we wouldn't view as revolutionary. But there is nothing to say that a homosexual cannot also be a revolutionary.

- ^ a b c Porter, Ronald K. (2012). "CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR: A Rainbow in Black: The Gay Politics of the Black Panther Party". Counterpoints. 367. Peter Lang AG: 364–375. JSTOR 42981419. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ a b Sibalis, Michael. 2005. Gay Liberation Comes to France: The Front Homosexuel d'Action Révolutionnaire (FHAR), Published in 'French History and Civilization. Papers from the George Rudé Seminar. Volume 1.' PDF link

- ^ Voss, Jon. "Idag 50 år sedan den homosexuella revolutionen – Sverige var först i Europa med Prideprotester" [Today marks 50 years since the gay revolution - Sweden was first in Europe with Pride protests]. QX.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- ^ a b Altman, Dennis (1972). Homosexual: Oppression and Liberation. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. ISBN 9780207124594.

- ^ a b c Seidman, Steven (1997). "Identity and politics in a "postmodern" gay culture". Difference Troubles: Queering Social Theory and Sexual Politics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59043-3.

General and cited sources

[edit]- Hoffman, Amy (2007). An Army of Ex-Lovers: My Life at the Gay Community News. University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 978-1558496217.