Invasion literature

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2016) |

Invasion literature (also the invasion novel or the future war genre[1]) is a literary genre that was popular in the period between 1871 and the First World War (1914–1918). The invasion novel was first recognised as a literary genre in the UK, with the novella The Battle of Dorking: Reminiscences of a Volunteer (1871), an account of a German invasion of England, which, in the Western world, aroused the national imaginations and anxieties about hypothetical invasions by foreign powers; by 1914 the genre of invasion literature comprised over 400 novels and stories.[2]

The genre was influential in Britain in shaping politics, national policies, and popular perceptions in the years leading up to the First World War, and remains a part of popular culture to this day. Several of the books were written by or ghostwritten for military officers and experts of the day who believed that the nation would be saved if the particular tactic that they favoured was or would be adopted.[3]

Pre-"Dorking"

[edit]Nearly a century before the invasion literature genre became a true popular phenomenon after the publication of The Battle of Dorking in 1871, a mini-boom of invasion stories appeared soon after the French developed the hot-air balloon. Poems and plays that centred on armies of balloons invading England could be found in France, and even America. However, it was not until the Prussians used advanced technologies such as breech-loading artillery and railroads to defeat the French in the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 that the fear of invasion by a technologically superior enemy became more realistic.

In Europe

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2024) |

One of those stories is a history of the sudden and terrible invasion of England by the French, in the month of May, 1852, According to I.F. Clarke: Many feared that military weakness at home would invite attack from abroad; and for the rest of the century not a decade passed without an alarm of some kind about the dangers pressing upon the nation. After the coup d’état by Louis Napoleon, for instance, there were general fears that the French might attempt an invasion. In order to demonstrate the defenceless condition of the country an anonymous author wrote A History of the sudden and terrible invasion of England by the French … in May 1852 ( London, 1851). This was the first complete imaginary war of the future to be written in English, and it anticipated Chesney’s technique of giving a detailed account of the weaknesses that led to the disaster.

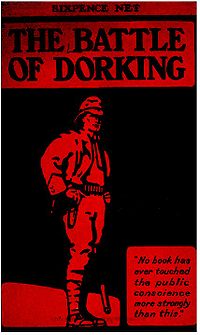

The novella, The Battle of Dorking: Reminiscences of a Volunteer (1871), by George Tomkyns Chesney was first published in Blackwood's Magazine, a respected political journal of the Victorian era.[4] The Battle of Dorking describes the invasion of England by an unnamed enemy (who speak German), in which the narrator and a thousand citizens defend the town of Dorking, with neither supplies, matériel, or news of outside world. The narrative of the story then moves forward fifty years in time, and England remains devastated.

The author, like many of his countrymen at the time, was alarmed by Prussia's successful invasion of France in 1870, defeating Europe's largest army in only two months.[2] The Battle of Dorking was initially meant to shock readers into becoming more aware of the possible dangers of a foreign threat, but unwittingly created a new literary genre appealing to popular anxieties. The story was an immediate success, with one reviewer saying "We do not know that we ever saw anything better in any magazine... it describes exactly what we all feel."[2] It was so popular that the magazine was re-printed six times, a new pamphlet version was created, dozens of spoofs were created, and it was for sale throughout the British Empire.[2] One running joke in England at the time was an injury, such as a bruise or scrape, being attributed to a wound received at the battle of Dorking.

Between the publication of The Battle of Dorking in 1871 and the start of the First World War in 1914 there were hundreds of authors writing invasion literature, often topping the best seller lists in Germany, France, England and the United States.[2] During the period it is estimated over 400 invasion works were published. Probably the best known work was H. G. Wells's The War of the Worlds (1897), bearing plot similarities to The Battle of Dorking but with a science fiction theme. In 1907, Wells wrote The War in the Air, a cautionary tale depicting purely human invasions: a German invasion of the US triggers off a worldwide chain of attacks and counter-attacks, leading to the destruction of all major cities and centers, the collapse of world economy, disintegration of all the fighting nations and the sinking of the world into new Middle Ages.

Dracula (1897) also tapped into English fears of foreign forces arriving unopposed on its shores, although between 1870 and 1903 the majority of these works assumed that the enemy would be France, rather than Germany. This changed with the publication of Erskine Childers's 1903 novel The Riddle of the Sands. Often called the first modern spy novel, two men on a sailing holiday thwart a German invasion of England when they discover a secret fleet of invasion barges assembling on the German coast. Of these hundreds of authors, few are in print now. Saki is one of the exceptions, although his 1913 novel When William Came (subtitled "A Story of London Under the Hohenzollerns") is more jingoistic than literary. Another is John Buchan, whose novel The Thirty-Nine Steps, published in 1915 but written just prior to the outbreak of World War I, is a thriller dealing with German agents in Britain preparing for an invasion.

William Le Queux was the most prolific author of the genre; his first novel was The Great War in England in 1897 (1894) and he went on to publish from one to twelve novels a year until his death in 1927. His work was regularly serialised in newspapers, particularly the Daily Mail, and attracted many readers. It is believed Ian Fleming's James Bond character was inspired by Le Queux's agent "Duckworth Drew".[5] In some ways The Great War can be considered an antithesis to The Battle of Dorking – with the one ending for Britain in sombre and irrevocable defeat and decline, while in the other the invasion of London is pushed back in the last moment (with the help of Germany, portrayed as a staunch ally against France and Russia), with enormous territorial aggrandizement (Britain gets Algeria and Russian Central Asia; "Britannia" becomes "Empress of the World").

Le Queux's most popular invasion novel was The Invasion of 1910 (1906) which was translated into twenty-seven languages selling more than a million copies world-wide. Le Queux and his publisher changed the ending depending on the language, so in the German print edition the fatherland wins, while in the English edition the Germans lose. Le Queux was said to be Queen Alexandra's favorite author.

P. G. Wodehouse parodied the genre in The Swoop!, in which England is simultaneously invaded by nine different armies, including Switzerland and Germany. English elites appear to be more interested in a cricket tournament, and the country is eventually saved by a boy scout named Clarence.

In France, Émile Driant writing as Capitaine Danrit, wrote of future wars opposing France to Great Britain (La Guerre Fatale) or to Germany (La Guerre de Demain).

In Asia

[edit]Invasion literature had its impact also in Japan, at the time undergoing a fast process of modernization. Shunrō Oshikawa, a pioneer of Japanese science fiction and adventure stories (genres unknown in Japan until a few years earlier), published around the start of the 20th century the best-seller Kaitō Bōken Kidan: Kaitei Gunkan ("Undersea Battleship"): the story of an armoured, ram-armed submarine involved in a future history of war between Japan and Russia. The novel reflected the imperialist ambitions of Japan at the time, and foreshadowed the Russo-Japanese War that followed a few years later, in 1904. The story would notably be the main source of inspiration for the 1963 science-fiction movie Atragon, by Ishiro Honda. When the actual war with Russia broke out, Oshikawa covered it as a journalist while also continuing to publish further volumes of fiction depicting Japanese imperial exploits set in the Pacific and Indian Ocean – which also proved an enormous success with the Japanese public. In a later career as a magazine editor, he also encouraged the writing of more fiction in the same vein by other Japanese authors.

Colonial Hong Kong's earliest work of invasion literature is believed to have been the 1897 The Back Door. Published in serial form in a local English-language newspaper, it described a fictional French and Russian naval landing at Hong Kong Island's Deep Water Bay; the story was intended to criticise the lack of British funding for the defence of Hong Kong, and it is speculated that members of the Imperial Japanese Army may have read the book in preparation for the 1941 Battle of Hong Kong.[6]

In the United States

[edit]

One of the earliest invasion stories to appear in print in the US was "The Stricken Nation" by Henry Grattan Donnelly published in 1890 in New York. It tells of a successful invasion of the US by the UK.[7] The move of U.S. public opinion towards participation in World War I was reflected in Uncle Sam's Boys at The Invasion of the United States by H. Irving Hancock. This four-book series, published by the Henry Altemus Company in 1916, depicts a German invasion of the US in 1920 and 1921. The plot seems to transfer the main story line of Le Queux's The Great War (with which the writer may have been familiar) to a US theatre: the Germans launch a surprise attack, capture Boston despite heroic resistance by "Uncle Sam's boys", overrun all of New England and New York and reach as far as Pittsburgh – but at last are gloriously crushed by fresh US forces.

In Australia

[edit]Australia's contribution to invasion literature was set against the background of pre-Federation colonial fears of the "Yellow Peril" and the foundations of the White Australia policy. From the late 1880s through to the beginning of World War I, this fear was expressed in Australia through cartoons, poems, plays and novels. Three of the most well known of these novels were White or Yellow? A Story of the Race War of AD 1908 (1888) by journalist William Lane, The Yellow Wave (1895) by Kenneth Mackay and The Australian Crisis (1909) by Charles H. Kirmess (possibly a pseudonym for another Australian author Frank Fox). Each of these novels contained two major common themes which were a reflection of the fears and concerns within a contemporary Australian context; the Australian continent was at risk of major invasion from a strong Asian power (ie. China or Japan, sometimes with the assistance of the Russian Empire) and that the United Kingdom was apathetic towards the protection of its faraway colonies, and would not come to Australia's aid when needed.[8]

After World War I

[edit]The "First Red Scare" following World War I produced Edgar Rice Burroughs's The Moon Men (1925), a depiction of Earth (and specifically, the United States) under the rule of cruel invaders from the Moon. This book is known to have been originally written as Under the Red Flag, an explicit anti-Communist novel, and when rejected by the publishers in that form it was successfully "recycled" by Burroughs as science fiction.

Ivan Petrushevich's The Flying Submarine (1922) depicts an invasion of the United Kingdom by Soviet forces after most of Europe and Asia fall to communism. The story features the British fleet being destroyed by a swarm of insect-like single pilot submarines, which can emerge from the water to attack their foes.

Robert A. Heinlein's Sixth Column (1941) told the story of the invasion and conquest of the United States by the technologically advanced PanAsians, and the subsequent guerrilla struggle to overthrow them with even more advanced technology.

The Cold War

[edit]In the 1950s, US fears of Communist invasion were notable in the novel The Puppet Masters (1951), by Robert A. Heinlein, the movie Invasion, USA (1952), directed by Alfred E. Green, and the US Defence Department propaganda film Red Nightmare (1957), directed by George Waggner. An explicit invasion-and-occupation scenario is presented in Point Ultimate (1955), by Jerry Sohl, about life in the Soviet-occupied US of 1999.

In the 1960s, the invasion literature enemy changed from the political threat of Communist infiltration and indoctrination from and conquest by the Soviets, to the 19th-century Yellow Peril of "Red China" (the People's Republic of China) who threaten the economy, the political stability, and the physical integrity of the US, and thus of the Western world. In Goldfinger (1964) Communist China provides the villain with a dirty atomic bomb to irradiate and render useless the gold bullion that is the basis of the US economy. In You Only Live Twice (1967), the PRC disrupts the geopolitical balance between the US and the Soviets, by the kidnapping of their respective spacecraft in outer space, to provoke a nuclear war, which would allow Chinese global supremacy. In Battle Beneath the Earth (1967), the PRC attempt to invade the US proper by way of a tunnel beneath the Pacific Ocean.

In 1971, when the US began acknowledging that the Vietnam War (1955–1975) was a loss, two books depicting the Soviet occupation of the continental US were published; the cautionary tale Vandenberg (1971), by Oliver Lange, wherein most of the US accepts the Soviet overlord without much protest, and the only armed resistance is by guerrillas in New Mexico; and The First Team (1971), by John Ball, which depicts a hopeless situation resolved by a band of patriots, which concludes with the country's liberation. The film Red Dawn (1984) depicts a Soviet/Cuban invasion of the United States and a band of high school students who resist them. The television miniseries Amerika (1987), directed by Donald Wrye, depicts life in the US a decade after the Soviet conquest.

The Tomorrow series (1993–1999) by John Marsden, details the perspective of adolescent guerrillas fighting against the invasion of Australia, by an unnamed country (implied to be Indonesia).

Political impact

[edit]Stories of a planned German invasion rose to increasing political prominence from 1906. Taking their inspiration from the stories of Le Queux and Childers, hundreds of ordinary citizens began to suspect foreigners of espionage. This trend was accentuated by Le Queux, who collected 'sightings' brought to his attention by readers and raised them through his association with the Daily Mail. Subsequent research has since shown that no significant German espionage network existed in Britain at this time. Claims about the scale of German invasion preparations grew increasingly ambitious. The number of German spies was put at between 60,000 and 300,000 (in spite of the total German community in Britain being no more than 44,000 people). It was alleged that thousands of rifles were being stockpiled by German spies in order to arm saboteurs at the outbreak of war.

Calls for government action grew ever more intense, and in 1909 it was given as the reason for the secret foundation of the Secret Service Bureau, the forerunner of MI5 and MI6. Historians today debate whether this was in fact the real reason, but in any case the concerns raised in invasion literature came to define the early duties of the Bureau's Home Section. Vernon Kell, the section head, remained obsessed with the location of these saboteurs, focusing his operational plans both before and during the war on defeating the saboteurs imagined by Le Queux.

Invasion literature was not without detractors; policy experts in the years preceding the First World War said invasion literature risked inciting war between England and Germany and France. Critics such as Prime Minister Henry Campbell-Bannerman denounced Le Queux's The Invasion of 1910 as "calculated to inflame public opinion abroad and alarm the more ignorant public at home."[2] Journalist Charles Lowe wrote in 1910: "Among all the causes contributing to the continuance of a state of bad blood between England and Germany perhaps the most potent is the baneful industry of those unscrupulous writers who are forever asserting that the Germans are only awaiting a fitting opportunity to attack us in our island home and burst us up."[2]

Notable invasion literature

[edit]

Pre-World War I

[edit]- The Battle of Dorking (1871) by George Tomkyns Chesney

- A Catástrofe (ca. 1878) by José Maria Eça de Queiroz

- La Guerre de demain (1888) by Émile Driant

- The Battle of Mordialloo (1888) by Samuel Mullen

- White or Yellow? A Story of the Race War of AD 1908 (1888) by William Lane

- The Stricken Nation (1890) by Henry Grattan Donnelly

- Hartmann the Anarchist (1893) by Edward Douglas Fawcett

- The Angel of the Revolution (1893) by George Griffith

- Olga Romanoff (1894) by George Griffith

- The Captain of the Mary Rose (1894) by William Laird Clowes

- The Great War in England in 1897 (1894) by William Le Queux

- The Yellow Wave (1895) by Kenneth Mackay

- The Final War (1896) by Louis Tracy

- Briton or Boer? A Tale of the Fight for Africa (1897) by George Griffith

- The Back Door (1897) by Anonymous

- The Yellow Danger (1898) by M. P. Shiel

- The War of the Worlds (1898) by H. G. Wells

- The Riddle of the Sands (1903) by Erskine Childers

- The Invasion of 1910 (1906) by William Le Queux

- The Australian Crisis (1907) by C. H. Kirmess

- The War in the Air (1908) by H. G. Wells

- Spies of the Kaiser (1909) by William Le Queux

- The Swoop! or How Clarence Saved England: A Tale of the Great Invasion (1909), by P. G. Wodehouse

- White Australia or, The Empty North (1909) by Randolph Bedford

- The Unparalleled Invasion (1910) by Jack London

- Private Selby (1912) by Edgar Wallace

- When William Came (1913) by Saki

- The World Set Free (1914) by H. G. Wells

- All For His Country (1915) by John Ulrich Giesy

- The Fall of a Nation (1916) by Thomas Dixon Jr.

- Conquest of the United States (1916) by H. Irving Hancock

- Before Armageddon: An Anthology of Victorian and Edwardian Imaginative Fiction Published Before 1914 edited by Michael Moorcock (1975)

- England Invaded (1977), a collection of six popular invasion literature stories, edited by Michael Moorcock, published in 1977

Post-World War I

[edit]- The Terror of the Air by William Le Queux (1920)

- The Flying Submarine by Ivan Petrushevich (1922)

- The Absolute at Large (1922) by Karel Čapek

- The Moon Men by Edgar Rice Burroughs (1925)

- The Tunnel Thru the Air; Or, Looking Back from 1940 by William Delbert Gann (1927)

- Armageddon 2419 A.D. by Philip Francis Nowlan (1928)

- The Airlords of Han by Philip Francis Nowlan (1929)

- The Red Napoleon by Floyd Gibbons (1929)

- War with the Newts (1936) by Karel Čapek

- Fools' Harvest (1939) by Erle Cox

- The Death Guard by Philip George Chadwick (1939)

- Sixth Column by Robert A. Heinlein (1941)

- The Puppet Masters by Robert A. Heinlein (1951)

- The Mouse That Roared (1955) Leonard Wibberley

- Not This August by C.M. Kornbluth (1955)

- Point Ultimate by Jerry Sohl (1955)

- A Piece of Resistance (1970) by Clive Egleton

- The First Team (1971) by John Ball

- Vandenberg (1971) by Oliver Lange

- Rule Britannia (novel) (1972) by Daphne du Maurier

- Operaatio Finlandia by Arto Paasilinna (1972)

- The Texas-Israeli War: 1999 (1974) by Jake Saunders (writer) and Howard Waldrop

- The Third World War: August 1985 (1978) and The Third World War: The Untold Story (1982) by General Sir John Hackett

- The Survivalist series (1981–1993) by Jerry Ahern

- Red Storm Rising (1986) by Tom Clancy

- Red Army (novel) (1989) by Ralph Peters

- The War in 2020 (1991) Ralph Peters

- Cauldron (Bond novel) (1993) by Larry Bond

- Tomorrow series (1993–1999) by John Marsden

- Debt of Honor (1994) Tom Clancy

- The Ashes series (1983–2003) by William W. Johnstone

- Protect and Defend (1999) by Eric L. Harry

- Invasion (Harry novel) by Eric L. Harry (2000)

- The Bear and the Dragon (2000) Tom Clancy

See also

[edit]- Alien invasion

- Alternate history

- Yellow Peril

- Lebor Gabála Érenn

- The Airship Destroyer

- The Aerial Anarchists

- Australia Calls (1913 film)

- The Battle Cry of Peace

- The Fall of a Nation

- Womanhood, the Glory of the Nation

- Victory and Peace

- Men Must Fight

- Face to Face with Communism

- Invasion, U.S.A. (1952 film)

- Rocket Attack U.S.A.

- Red Nightmare (1962)

- The War Game

- Battle Beneath the Earth

- Future War 198X

- Red Dawn (1984)

- Invasion U.S.A. (1985 film)

- Saikano

- Aetheric Mechanics

- Tomorrow, When the War Began (film)

- Red Dawn (2012 film)

- Steel Rain

- The Unthinkable (2018 film)

- World War III in popular culture

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Stableford, Brian (2022). "Future War". In Clute, John; Langford, David; Sleight, Graham (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (4th ed.). Retrieved 2023-08-26.

- ^ a b c d e f g Reiss 2005.

- ^ Echevarria, Antonio J. (2007). Imagining Future War: The West's Technological Revolution and Visions of Wars to Come 1880–1914. Prager Institute. ISBN 9780313051104.

- ^ Kirkwood, Patrick M. (Fall 2012). "The Impact of Fiction on Public Debate in Late Victorian Britain: The Battle of Dorking and the 'Lost Career' of Sir George Tomkyns Chesney". The Graduate History Review. 4 (1): 1–16.

- ^ Calavita, Marco (28 July 2012). "A Nod to the Xenophobic, Lying Inventor of Spy Fiction". Wired.

- ^ Bickley, Gillian (2001). Hong Kong Invaded! A 97 Nightmare. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 962-209-526-7.

- ^ Clarke, I. F., ed. (1995). Tales of the Next Great War. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 081562672X.

- ^ Curran, James; Ward, Stuart, eds. (2013). Australia and the Wider World: Selected Essays of Neville Meaney. Sydney University Press. ISBN 9781743320259.

References

[edit]- Affeldt, Stefanie (2011). "'White' Nation – 'White' Angst. The Literary Invasion of Australia". In Wigger, Iris; Ritter, Sabine (eds.). Racism and Modernity. Berlin: Lit. pp. 222–235. ISBN 9783643901491.

- Christopher, Andrew (1985). Secret Service: the making of the British intelligence community. ISBN 0-434-02110-5.

- Clarke, I. F. (1992) [1966]. Voices Prophesying War: Future Wars, 1763–3749. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-212302-5.

- Reiss, Tom (November 28, 2005). "Imagining the Worst: How a literary genre anticipated the modern world". The New Yorker. pp. 106–114.

Further reading

[edit]- Stableford, Brian (May 1994). Pringle, David (ed.). "Yesterday's Bestsellers 19: "The Battle of Dorking" and Its Aftermath". Interzone. No. 83. pp. 52–56. ISSN 0264-3596.

External links

[edit]- Clarke, I.F., 1997. "Future War Fiction". An award-winning essay.

- Clarke, I.F., 1997. "Before and After The Battle of Dorking".

- George Tomkyns Chesney (1871). The Battle of Dorking. London, G. Richards ltd., 1914, introduction by G. H. Powell. From Internet Archive.

- Patrick M. Kirkwood, "The Impact of Fiction on Public Debate in Late Victorian Britain: The Battle of Dorking and the 'Lost Career' of Sir George Tomkyns Chesney", The Graduate History Review 4, No. 1 (Fall, 2012), 1-16.