Fun Home

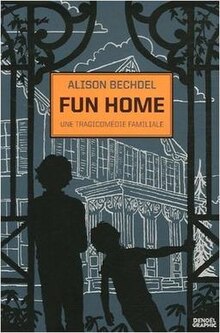

Cover of the hardback edition | |

| Author | Alison Bechdel |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Alison Bechdel |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Graphic novel, Memoir |

| Publisher | Houghton Mifflin (hardcover); Mariner Books (paperback) |

Publication date | June 8, 2006 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardcover, paperback) |

| Pages | 240 p. |

| ISBN | [[Special:BookSources/ISBN+0-618-47794-2+%28hardcover%29%3B%3Cbr%3EISBN+0-618-87171-3+%28paperback%29 |ISBN 0-618-47794-2 (hardcover); ISBN 0-618-87171-3 (paperback)]] Parameter error in {{ISBNT}}: invalid character |

| OCLC | 62127870 |

| 741.5/973 22 | |

| LC Class | PN6727.B3757 Z46 2006 |

Fun Home (subtitled A Family Tragicomic) is a graphic memoir by Alison Bechdel, author of the comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For. It chronicles the author's childhood and youth in rural Pennsylvania, USA, focusing on her complex relationship with her father. The book addresses themes of sexual orientation, gender roles, suicide, dysfunctional family life, and the role of literature in understanding oneself and one's family. Writing and illustrating Fun Home took seven years, in part because of Bechdel's laborious artistic process, which includes photographing herself in poses for each human figure.[1][2][3][4]

Fun Home has been both a popular and critical success, and spent two weeks on the New York Times Best Seller list.[5][6] In The New York Times Sunday Book Review, Sean Wilsey called it "a pioneering work, pushing two genres (comics and memoir) in multiple new directions."[7] Several publications named Fun Home as one of the best books of 2006; it was also included in several lists of the best books of the 2000s.[8] It was nominated for several awards, including the National Book Critics Circle Award and three Eisner Awards (one of which it won).[8][9] A French translation of Fun Home was serialized in the newspaper Libération; the book was an official selection of the Angoulême International Comics Festival and has been the subject of an academic conference in France.[10][11][12] Fun Home has been the subject of numerous academic publications in areas such as biography studies and cultural studies, as part of a larger turn towards serious academic investment in the study of comics/sequential art.[13]

Fun Home also generated controversy: a public library in Missouri removed Fun Home from its shelves for five months after local residents objected to its contents.[14][15]

Plot and thematic summary

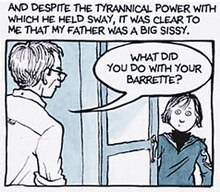

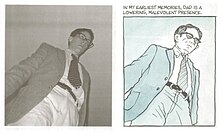

Bruce (left) and Alison Bechdel

The narrative of Fun Home is non-linear and recursive.[16] Incidents are told and re-told in the light of new information or themes.[17] Bechdel describes the structure of Fun Home as a labyrinth, "going over the same material, but starting from the outside and spiraling in to the center of the story."[18] In an essay on memoirs and truth in the academic journal PMLA, Nancy K. Miller explains that as Bechdel revisits scenes and themes "she re-creates memories in which the force of attachment generates the structure of the memoir itself."[19] Additionally, the memoir derives its structure from allusions to various works of literature, Greek myth and visual arts; the events of Bechdel's family life during her childhood and adolescence are presented through this allusive lens.[16] Miller notes that the narratives of the referenced literary texts "provide clues, both true and false, to the mysteries of family relations."[19]

The memoir centers on Alison Bechdel's family but gives particular attention to her relationship with her father, Bruce. Bruce Bechdel was a funeral director and high school English teacher in Beech Creek, where Alison and her siblings grew up. The book's title comes from the family nickname for the funeral home, the family business in which Bruce Bechdel grew up and later worked.[20] His two occupations are reflected in Fun Home's focus on death and literature.[21]

On one level, the memoir traces Bruce Bechdel's obsession with restoring the family's Victorian home.[21] His concentrated pursuit of this long-term aesthetic quest is connected to his emotional distance from his family, which he expressed in coldness and occasional bouts of abusive rage.[21][22] This emotional distance, in turn, is connected with his closeted homosexual tendencies.[23] Bruce Bechdel had homosexual relationships in the military and with his high school students; some of those students were also family friends and babysitters.[24] At the age of 44, two weeks after his wife requested a divorce, he stepped into the path of an oncoming Sunbeam Bread truck and was killed.[25] Although the evidence is equivocal, Alison Bechdel concludes that her father committed suicide.[21][26][27]

The story also deals with Alison Bechdel's own struggle with her sexual identity, culminating in the realization that she is a lesbian and her coming out to her parents.[21][28] The memoir frankly examines her sexual development, including transcripts from her childhood diary, anecdotes about masturbation, and tales of her first sexual experiences.[29] In addition to their common homosexuality, Alison and Bruce Bechdel share obsessive-compulsive tendencies and artistic leanings, albeit with opposing aesthetic senses: "I was Spartan to my father's Athenian. Modern to his Victorian. Butch to his nelly. Utilitarian to his aesthete."[30] This opposition was a source of tension in their relationship, as both tried to express their dissatisfaction with their given gender roles: "Not only were we inverts, we were inversions of each other. While I was trying to compensate for something unmanly in him, he was attempting to express something feminine through me. It was a war of cross-purposes, and so doomed to perpetual escalation."[31] However, shortly before Bruce Bechdel's death, he and his daughter have a conversation which is presented as a partial resolution to this conflict.[32]

At several points in the book, Bechdel questions whether her decision to come out as a lesbian was one of the triggers for her father's suicide.[19][33] This question is never answered definitively, but Bechdel closely examines the connection between her father's closeted sexuality and her own open lesbianism, revealing her debt to her father in both positive and negative lights.[19][21][27]

Allusions

The allusive references used in Fun Home are not merely structural or stylistic: Bechdel writes, "I employ these allusions ... not only as descriptive devices, but because my parents are most real to me in fictional terms. And perhaps my cool aesthetic distance itself does more to convey the Arctic climate of our family than any particular literary comparison."[34] Bechdel, as the narrator, considers her relationship to her father through the myth of Daedalus and Icarus.[35] As a child, she confused her family and their Gothic Revival home with the Addams Family seen in the cartoons of Charles Addams.[36] Bruce Bechdel's suicide is discussed with reference to Albert Camus' novel A Happy Death and essay The Myth of Sisyphus.[37] His careful construction of an aesthetic and intellectual world is compared to The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, and the narrator suggests that Bruce Bechdel modeled elements of his life after Fitzgerald's, as portrayed in the biography The Far Side of Paradise.[38] His wife Helen is compared with the protagonists of the Henry James novels Washington Square and The Portrait of a Lady.[39] Helen Bechdel was an amateur actress, and plays in which she acted are also used to illuminate aspects of her marriage. She met Bruce Bechdel when the two were appearing in a college production of The Taming of the Shrew, and Alison Bechdel intimates that this was "a harbinger of my parents' later marriage".[40] Helen Bechdel's role as Lady Bracknell in a local production of The Importance of Being Earnest is shown in some detail; Bruce Bechdel is compared with Oscar Wilde.[41] His homosexuality is also examined with allusion to Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time.[42] The father and daughter's artistic and obsessive-compulsive tendencies are discussed with reference to E. H. Shepard's illustrations for The Wind in the Willows.[43] Bruce and Alison Bechdel exchange hints about their sexualities by exchanging memoirs: the father gives the daughter Earthly Paradise, an autobiographical collection of the writings of Colette; shortly afterwards, in what Alison Bechdel describes as "an eloquent unconscious gesture", she leaves a library copy of Kate Millett's memoir Flying for him.[44] Finally, returning to the Daedalus myth, Alison Bechdel casts herself as Stephen Dedalus and her father as Leopold Bloom in James Joyce's Ulysses, with parallel references to the myth of Telemachus and Odysseus.[45]

In addition to the literary allusions which are explicitly acknowledged in the text, Bechdel incorporates visual allusions to television programs and other items of pop culture into her artwork, often as images on a television in the background of a panel.[23] These visual references include the film It's a Wonderful Life, Bert and Ernie of Sesame Street, the Smiley Face, Yogi Bear, Batman, the Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote, the resignation of Richard Nixon and The Flying Nun.[23][46]

Artwork

Fun Home is drawn in black line art with a gray-green ink wash.[2] Sean Wilsey wrote that Fun Home's panels "combine the detail and technical proficiency of R. Crumb with a seriousness, emotional complexity and innovation completely its own."[7] Writing in the Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide, Diane Ellen Hamer contrasted "Bechdel's habit of drawing her characters very simply and yet distinctly" with "the attention to detail that she devotes to the background, those TV shows and posters on the wall, not to mention the intricacies of the funeral home as a recurring backdrop."[23] Bechdel told an interviewer for The Comics Journal that the richness of each panel of Fun Home was very deliberate:

It's very important for me that people be able to read the images in the same kind of gradually unfolding way as they're reading the text. I don't like pictures that don't have information in them. I want pictures that you have to read, that you have to decode, that take time, that you can get lost in. Otherwise what's the point?[47]

Bechdel wrote and illustrated Fun Home over the course of seven years.[1] Her laborious artistic process made the task of illustration slow. She began each page by creating a framework in Adobe Illustrator, on which she placed the text and drew rough figures.[2][3] She used extensive photo reference and, for many panels, posed for each human figure herself, using a digital camera to record her poses.[2][3][4][27] Bechdel also used photo reference for background elements. For example, to illustrate a panel depicting fireworks seen from a Greenwich Village rooftop on July 4, 1976, she used Google Images to find a photograph of the New York skyline taken from that particular building in that period.[3][48][49] She also painstakingly copied by hand many family photographs, letters, local maps and excerpts from her own childhood journal, incorporating these images into her narrative.[48] After using the reference material to draw a tight framework for the page, Bechdel copied the line art illustration onto plate finish Bristol board for the final inked page, which she then scanned into her computer.[2][3] The gray-green ink wash for each page was drawn on a separate page of watercolor paper, and combined with the inked image using Photoshop.[2][3][27] Bechdel chose the greenish wash color for its flexibility, and because it had "a bleak, elegiac quality" which suited the subject matter.[50] Bechdel attributes this detailed creative process to her "barely controlled obsessive-compulsive disorder".[48][51]

Publication and reception

Fun Home was first printed in hardcover by Houghton Mifflin (Boston, New York) on June 8, 2006.[52] This edition appeared on the New York Times' Hardcover Nonfiction bestseller list for two weeks, covering the period from June 18 to July 1, 2006.[5][6] It continued to sell well, and by February 2007 there were 55,000 copies in print.[53] A trade paperback edition was published in the United Kingdom by Random House under the Jonathan Cape imprint on September 14, 2006; Houghton Mifflin published a paperback edition under the Mariner Books imprint on June 5, 2007.[54][55]

In the summer of 2006, a French translation of Fun Home was serialized in the Paris newspaper Libération (which had previously serialized Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi).[10] This translation, by Corinne Julve and Lili Sztajn, was subsequently published by Éditions Denoël on October 26, 2006.[56] In January 2007, Fun Home was an official selection of the Angoulême International Comics Festival.[11] In the same month, the Anglophone Studies department of the Université François Rabelais, Tours sponsored an academic conference on Bechdel's work, with presentations in Paris and Tours.[12] At this conference, papers were presented examining Fun Home from several perspectives: as containing "trajectories" filled with paradoxical tension; as a text interacting with images as a paratext; and as a search for meaning using drag as a metaphor.[57][58][59] These papers and others on Bechdel and her work were later published in the peer-reviewed journal GRAAT (Groupe de Recherches Anglo-Américaines de Tours, or Tours Anglo-American Research Group).[60][61]

An Italian translation was published by Rizzoli in January 2007.[62][63] A German translation was published by Kiepenheuer & Witsch in January 2008.[64] The book has also been translated into Hungarian, Korean, and Polish,[65] and a Chinese translation has been scheduled for publication.[66]

In October 2006, a resident of Marshall, Missouri attempted to have Fun Home and Craig Thompson's Blankets, both graphic novels, removed from the city's public library.[67] Supporters of the books' removal characterized them as "pornography" and expressed concern that they would be read by children.[14][68] Marshall Public Library Director Amy Crump defended the books as having been well-reviewed in "reputable, professional book review journals," and characterized the removal attempt as a step towards "the slippery slope of censorship".[67][68] On October 11, 2006, the library's board appointed a committee to create a materials selection policy, and removed Fun Home and Blankets from circulation until the new policy was approved.[69][70] The committee "decided not to assign a prejudicial label or segregate [the books] by a prejudicial system", and presented a materials selection policy to the board.[71][72] On March 14, 2007, the Marshall Public Library Board of Trustees voted to return both Fun Home and Blankets to the library's shelves.[15] Bechdel described the attempted banning as "a great honor", and described the incident as "part of the whole evolution of the graphic-novel form."[73]

In 2008, an instructor at the University of Utah placed Fun Home on the syllabus of a mid-level English course, "Critical Introduction to English Literary Forms".[74] One student objected to the assignment, and was given an alternate reading in accordance with the university's religious accommodation policy.[74] The student subsequently contacted a local organization called "No More Pornography", which started an online petition calling for the book to be removed from the syllabus.[75] Vincent Pecora, the chair of the university's English department, defended Fun Home and the instructor.[75] The university said that it had no plans to remove the book.[75]

Reviews and awards

Fun Home was positively reviewed in many publications. The Times of London described Fun Home as "a profound and important book;" Salon.com called it "a beautiful, assured piece of work;" and The New York Times ran two separate reviews and a feature on the memoir.[7][21][76][77][78] In one New York Times review, Sean Wilsey called Fun Home "a pioneering work, pushing two genres (comics and memoir) in multiple new directions" and "a comic book for lovers of words".[7] Jill Soloway, writing in the Los Angeles Times, praised the work overall but commented that Bechdel's reference-heavy prose is at times "a little opaque".[79] Similarly, a reviewer in The Tyee felt that "the narrator's insistence on linking her story to those of various Greek myths, American novels and classic plays" was "forced" and "heavy-handed".[49] By contrast, the Seattle Times' reviewer wrote positively of the book's use of literary reference, calling it "staggeringly literate".[80] The Village Voice said that Fun Home "shows how powerfully—and economically—the medium can portray autobiographical narrative. With two-part visual and verbal narration that isn't simply synchronous, comics presents a distinctive narrative idiom in which a wealth of information may be expressed in a highly condensed fashion."[16]

Several publications listed Fun Home as one of the best books of 2006, including The New York Times, Amazon.com, The Times of London, New York magazine and Publishers Weekly, which ranked it as the best comic book of 2006.[81][82][83][84][85][86] Salon.com named Fun Home the best nonfiction debut of 2006, admitting that they were fudging the definition of "debut" and saying, "Fun Home shimmers with regret, compassion, annoyance, frustration, pity and love—usually all at the same time and never without a pervasive, deeply literary irony about the near-impossible task of staying true to yourself, and to the people who made you who you are."[87] Entertainment Weekly called it the best nonfiction book of the year, and Time named Fun Home the best book of 2006, describing it as "the unlikeliest literary success of 2006" and "a masterpiece about two people who live in the same house but different worlds, and their mysterious debts to each other." [88][89]

Fun Home was a finalist for the 2006 National Book Critics Circle Award, in the memoir/autobiography category.[90][91] In 2007, Fun Home won the GLAAD Media Award for Outstanding Comic Book, the Stonewall Book Award for non-fiction, the Publishing Triangle-Judy Grahn Nonfiction Award, and the Lambda Literary Award in the "Lesbian Memoir and Biography" category.[92][93][94][95] Fun Home was nominated for the 2007 Eisner Awards in two categories, Best Reality-Based Work and Best Graphic Album, and Bechdel was nominated as Best Writer/Artist.[96] Fun Home won the Eisner for Best Reality-Based Work.[9] In 2008, Entertainment Weekly placed Fun Home at #68 in its list of "New Classics" (defined as "the 100 best books from 1983 to 2008").[97] The Guardian included Fun Home in its series "1000 novels everyone must read", noting its "beautifully rendered" details.[98]

In 2009, Fun Home was listed as one of the best books of the previous decade by The Times of London, Entertainment Weekly and Salon.com, and as one of the best comic books of the decade by The Onion's A.V. Club.[8][99]

References

- ^ a b Emmert, Lynn (April 2007). "Life Drawing". The Comics Journal (282). Seattle, Washington: Fantagraphics Books: 36. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Emmert, Lynn (April 2007). "Life Drawing". The Comics Journal (282). Seattle, Washington: Fantagraphics Books: 44–48. Print edition only.

- ^ a b c d e f Harrison, Margot (May 31, 2006). "Life Drawing". Seven Days. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ^ a b Bechdel, Alison (April 18, 2006). "OCD" (video). YouTube. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ a b "Hardcover Nonfiction" (free registration required). The New York Times. July 9, 2006. Retrieved December 18, 2006.

- ^ a b "Hardcover Nonfiction" (free registration required). The New York Times. July 16, 2006. Retrieved December 18, 2006.

- ^ a b c d Wilsey, Sean (June 18, 2006). "The Things They Buried" (free registration required). Sunday Book Review. The New York Times. Retrieved August 7, 2006.

{{cite news}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - ^ a b c Bechdel, Alison. "News and Reviews". dykestowatchoutfor.com. Retrieved December 14, 2009.

- ^ a b "The 2007 Eisner Awards: Winners List". San Diego Comic-Con website. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ^ a b Bechdel, Alison (July 26, 2006). "Tour de France". Blog. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ a b "Official 2007 Selection". Angoulême International Comics Festival. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ a b Cherbuliez, Juliette (January 25, 2007). "There's No Place like (Fun) Home". Transatlantica. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ e.g. Tolmie, Jane (2009). “Modernism, Memory and Desire: Queer Cultural Production in Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home.” Topia: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies. 22: 77-96;

Watson, Julia (2008). “Autographic Disclosures and Genealogies of Desire in Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home.” Biography. 31.1: 27-58. - ^ a b Twiddy, David (November 14, 2006). "As more graphic novels appear in libraries, so do challenges". Associated Press. International Herald Tribune. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- ^ a b Harper, Rachel (March 15, 2007). "Library board approves new policy/Material selection policy created, controversial books returned to shelves". The Marshall Democrat-News. Retrieved March 15, 2007.

- ^ a b c Chute, Hillary (July 11, 2006). "Gothic Revival". The Village Voice. Retrieved August 7, 2006.

- ^ Deppey, Dirk (January 17, 2007). "12 Days". The Comics Journal (Web Extras ed.). Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- ^ Bechdel, Alison (Interviewee), Seidel, Dena (Editor) (2008). Alison Bechdel's Graphic Narrative (Flash video) (Web video). New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Writers House. Event occurs at 04:57. Retrieved April 16, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Miller, Nancy K. (2007). "The Entangled Self: Genre Bondage in the Age of the Memoir" (subscription required for online access). PMLA. 122 (2): 543–544. doi:10.1632/pmla.2007.122.2.537. ISSN 0030-8129. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bechdel, Alison (2006). Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. New York: Houghton Mifflin. p. 36. ISBN 0-618-47794-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gustines, George Gene (June 26, 2006). "'Fun Home': A Bittersweet Tale of Father and Daughter" (free registration required). The New York Times. Retrieved August 7, 2006.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 11, 18, 21, 68–69, 71.

- ^ a b c d Hamer, Diane Ellen (2006). "My Father, My Self". Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide. 13 (3): 37. ISSN 1532-1118. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 58–59, 61, 71, 79, 94–95, 120.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 27–30, 59, 85.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 23, 27–29, 89, 116–117, 125, 232.

- ^ a b c d Bechdel, Alison. "Alison Bechdel: Comic Con 2007" (Flash Video) (Interview). Interviewed by Michelle Paradise. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

{{cite interview}}: Unknown parameter|program=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|subjectlink=ignored (|subject-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 58, 74–81,

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 76, 80–81, 140–143, 148–149, 153, 157–159, 162, 168–174, 180–181, 183–186, 207, 214–215, 224.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, p. 15.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, p. 98.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 57–59, 86, 117, 230–232.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, p. 67

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 3–4, 231–232.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 27–28, 47–49.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 61–66, 84–86.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 66–67, 70–71.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 154–155, 157–158, 163–168, 175, 180, 186.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 92–97, 102, 105, 108–109, 113, 119–120.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 130–131, 146–147, 150.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 205, 207–208, 217–220, 224, 229.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 201–216, 221–223, 226, 228–231.

- ^ Bechdel, Fun Home, pp. 10–11 (It's a Wonderful Life), 14 (Sesame Street), 15 (Smiley Face), 92 (Yogi Bear), 130 (Batman), 174–175 (Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote), 181 (Nixon), 131, 193 (The Flying Nun).

- ^ Emmert, p. 46. Print edition only.

- ^ a b c Swartz, Shauna (May 8, 2006). "Alison Bechdel's Life in the Fun Home". AfterEllen.com. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ^ a b Brooks, Carellin (August 23, 2006). "A Dyke to Watch Out For". The Tyee. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ^ Emmert, pp. 47–48. Print edition only.

- ^ Emmert, p. 45. Print edition only.

- ^ "Fun Home; ISBN 0618477942". Houghton Mifflin website. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- ^ "Comics Bestsellers: February 2007". Publishers Weekly. February 6, 2007. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- ^ "Book Details for Fun Home". Random House UK website. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- ^ "Fun Home; ISBN 0618871713". Houghton Mifflin website. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- ^ "Fun Home". Éditions Denoël website (in French). Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ Chabani, Karim (March 2007). "Double Trajectories: Crossing Lines in Fun Home" (PDF). GRAAT. on-line edition (1). Tours: Université François Rabelais. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ Muller, Agnés (March 2007). "Image as Paratext in Alison Bechdel's Fun Home" (PDF). GRAAT. on-line edition (1). Tours: Université François Rabelais. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ Tison, Hélène (March 2007). "Drag as metaphor and the quest for meaning in Alison Bechdel's Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic" (PDF). GRAAT. on-line edition (1). Tours: Université François Rabelais. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ Tison, Hélène, ed. (March 2007). "Reading Alison Bechdel". GRAAT. on-line edition (1). Tours: Université François Rabelais. Retrieved October 14, 2008.

{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Groupe de Recherches Anglo-Américaines de Tours". Université François Rabelais, Tours (in French). Retrieved August 21, 2007.

- ^ "Fun Home". Rizzoli (in Italian). RCS MediaGroup. Retrieved August 14, 2009.

- ^ "Libro Fun Home". Libraria Rizzoli (in Italian). RCS MediaGroup. Retrieved August 14, 2009.

- ^ "Fun Home" (in German). Kiepenheuer & Witsch. 2008. Retrieved April 16, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Abiekt.pl (October 9, 2008). "Fun Home. Tragikomiks rodzinny". abiekt.pl (in Polish). Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ Bechdel, Alison (August 14, 2008). "china, translated". dykestowatchoutfor.com. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- ^ a b Sims, Zach (October 3, 2006). "Library trustees to hold hearing on novels". The Marshall Democrat-News. Retrieved October 8, 2006.

- ^ a b Sims, Zach (October 5, 2006). "Library board hears complaints about books/Decision scheduled for Oct. 11 meeting". The Marshall Democrat-News. Retrieved October 8, 2006.

- ^ Brady, Matt (October 12, 2006). "Marshall Libaray Board Votes to Adopt Materials Selection Policy". Newsarama. Retrieved October 12, 2006.

- ^ Sims, Zach (October 12, 2006). "Library board votes to remove 2 books while policy for acquisitions developed". The Marshall Democrat-News. Retrieved October 12, 2006.

- ^ Harper, Rachel (January 25, 2007). "Library board ready to approve new materials selection policy". The Marshall Democrat-News. Retrieved January 26, 2007.

- ^ Harper, Rachel (February 8, 2007). "Library policy has first reading". The Marshall Democrat-News. Retrieved March 5, 2007.

- ^ Emmert, p. 39. Retrieved on August 6, 2007.

- ^ a b Vanderhooft, JoSelle (April 7, 2008). "Anti-Porn Group Challenges Gay Graphic Novel". QSaltLake. Retrieved April 16, 2008.

- ^ a b c Dallof, Sarah (March 27, 2008). "Students protesting book used in English class". KSL-TV. Retrieved April 16, 2008.

- ^ Wolk, Douglas (June 5, 2006). "Fun Home". Salon.com. Retrieved August 12, 2006.

- ^ Reynolds, Margaret (September 16, 2006). "Images of the fragile self". The Times. London. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ^ Bellafante, Ginia (August 3, 2006). "Twenty Years Later, the Walls Still Talk" (paid archive). The New York Times. Retrieved August 7, 2006.

- ^ Soloway, Jill (June 4, 2006). "Skeletons in the closet" (paid archive). Los Angeles Times. p. R. 12. Retrieved August 1, 2007.

- ^ Pachter, Richard (June 16, 2006). ""Fun Home": Sketches of a family circus". Seattle Times. Retrieved August 9, 2007.

- ^ "100 Notable Books of the Year" (free registration required). Sunday Book Review. The New York Times. December 3, 2006. Retrieved December 12, 2006.

- ^ "Best Books of 2006: Editors' Top 50". amazon.com. Retrieved December 18, 2006.

- ^ "Best of 2006 Top 10 Editors' Picks: Memoirs". amazon.com. Retrieved December 18, 2006.

- ^ Gatti, Tom (December 16, 2006). "The 10 best books of 2006: number 10 — Fun Home". The Times. London. Retrieved December 18, 2006.

- ^ Bonanos, Christopher (December 18, 2006 cover date). "The Year in Books". New York. Retrieved December 12, 2006.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "The First Annual PW Comics Week Critic's Poll". Publishers Weekly Online. Publishers Weekly. December 19, 2006. Retrieved December 19, 2006.

- ^ Miller, Laura (December 12, 2006). "Best debuts of 2006". salon.com. Retrieved December 12, 2006.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Reese, Jennifer (December 29, 2006). "Literature of the Year". Entertainment Weekly. No. 913–914. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- ^ Grossman, Lev (December 17, 2006). "10 Best Books". Time. Retrieved December 18, 2006.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Getlin, Josh (January 21, 2007). "Book Critics Circle nominees declared" (free abstract of paid archive). Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- ^ "NBCC Awards Finalists". National Book Critics Circle website. Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- ^ "18th Annual GLAAD Media Awards in San Francisco". Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- ^ "Holleran, Bechdel win 2007 Stonewall Book Awards" (PDF). Cognotes. American Library Association. January 22, 2007. p. 4. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- ^ "Alison Bechdel Among Triangle Award Winners". The Book Standard. May 8, 2007. p. 1. Retrieved May 9, 2007.

- ^ "Lambda Literary Awards Announce Winners". Lambda Literary Foundation. Retrieved June 5, 2007.

- ^ "The 2007 Eisner Awards: 2007 Master Nominations List". San Diego Comic-Con website. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ^ "The New Classics: Books". Entertainment Weekly. No. 999–1000. June 27, 2008 cover date. Retrieved June 22, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Taylor, Craig (January 20, 2009). "1000 novels everyone must read: The best graphic novels". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved January 20, 2009.

- ^ "The 100 Best Books of the Decade". The Times. London. November 14, 2009. Retrieved December 14, 2009. Listed as #42 of 100.

"Books: The 10 Best of the Decade". Entertainment Weekly. December 3, 2009. Retrieved December 14, 2009. Listed as #7 of 10.

Miller, Laura (December 9, 2009). "The best books of the decade". Salon.com. Retrieved December 14, 2009. Listed chronologically in a list of 10 non-fiction works.

Handlen, Zack (November 24, 2009). "The best comics of the '00s". The A.V. Club. The Onion. Retrieved December 14, 2009.{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Listed alphabetically in a list of 25.

External links

- Houghton Mifflin's Fun Home press release, with excerpts from the book and video of Bechdel's artistic process

- dykestowatchoutfor.com, author Alison Bechdel's blog and official website

- What the Little Old Ladies Feel: How I told my mother about my memoir. Slate article by Bechdel