French invasion of Egypt and Syria

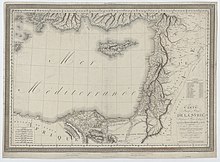

Egypt and Syria

| History of Egypt |

|---|

|

|

|

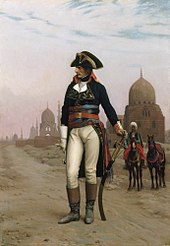

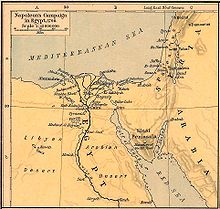

The French invasion of Egypt and Syria was a military campaign in and occupation of Ottoman territories in Egypt and Syria by French forces under the command of Napoleon during the French Revolutionary Wars. It was the primary purpose of the Mediterranean campaign of 1798, in which the French captured Malta while being followed by the British Royal Navy, whose pursuit was hampered by a lack of scouting frigates and reliable information.

The expedition was the result of a confluence of interests. The French Directory hoped to disrupt the trade routes of Great Britain and create a "double port" connecting the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. Napoleon proclaimed the invasion as being intended to defend French trade interests

and to establish scientific enterprise

in the region, and envisioned the campaign as the first step of a march to India, where he would join forces with Tipu Sultan, the ruler of French-allied Mysore who was at war with Britain, to attack British possessions in India.

Despite early victories in Egypt and an initially successful expedition into Syria, the destruction of a French Navy fleet by the British navy at the Battle of the Nile stranded French troops in Egypt, and the defeat of Napoleon and his Army of the Orient by Anglo-Ottoman forces at Acre forced the French to withdraw from Syria. Following his defeat in Syria, Napoleon repelled the Ottoman landing at Aboukir, but recognizing that the campaign was lost, and with the news of a Second Coalition reversing French conquests in Europe, Napoleon opportunistically abandoned his army, sailed to France, and overthrew the government. The French forces left in Egypt ultimately surrendered at Alexandria, concluding the defeat of Napoleon's expedition. These last French forces were repatriated, and the Treaty of Paris officially ended the hostilities between France and the Ottoman Empire.

On the scientific front, the expedition was a success that led to the publication of the Description de l'Égypte, and the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, creating the field of Egyptology. On the social and technological front, the expedition's legacy includes the re-introduction of the printing press to Egypt, the founding of the Institut d'Égypte, the rise of nationalism and liberalism in the Middle East, the emergence of modern European imperialism, and the popularization of Orientalist narratives of the Muslim world.

Background

[edit]The Peace of Campo Formio had ended the First War of the Coalition in France's favour. This left Great Britain as the only influential European country still at war with the French Republic.[5] After the defeats at St Vincent and Camperdown, which made an invasion of England impossible, the French government sought further methods to weaken Great Britain.[6]

The notion of annexing Egypt as a French colony had been under discussion since François Baron de Tott undertook a secret mission to the Levant in 1777 to determine its feasibility.. Baron de Tott's report was favourable, but no immediate action was taken. Nevertheless, Egypt became a topic of debate between Talleyrand and Napoleon, which continued in their correspondence during Napoleon's Italian campaign.[7]

The decision for Egypt

[edit]At the time Egypt had been under Ottoman sovereignty since the early 16th century. French merchants had been strongly represented there since the 15th century, and France maintained good relations with the Ottomans. However, Ismail Bey, the Mamluk Shaykh al-balad, who ruled Egypt on behalf of the Ottomans and was well-disposed towards the French, died in 1791 during an epidemic in Cairo. His rivals, Ibrahim Bey and Murad Bey, took power and took action against the French in the country. Exposed to more and more repression, the French merchants asked for intervention. France therefore had two formal reasons to intervene: Firstly, the Kingdom of France had been an ally of the Ottoman Sultan since 1536 and could claim to want to restore his authority. Secondly, since the French Revolution, France could argue that it also wanted to bring the Egyptians freedom from the yoke of feudal Mamluk rule. The decision of 1798 was a complex mixture of geostrategic, economic, political and personal interests, dressed up with the ideals of the French Revolution.[8] Napoleon regarded the capture of Egypt as the most important step to neutralise the massive economic advantages that Great Britain derived from trade with India and to force Great Britain to make concessions.[9] In August 1797, he wrote in a letter to the Directory:

Les temps ne sont pas éloignés, où nous sentirons que, pour détruire véritablement l'Angleterre, il faut nous emparer de l'Égypt.

The time is not far off when we will feel that to really destroy England we must take Egypt.

— Napoleon Bonaparte, [10]

The capture of Egypt would have given the French control of the eastern Mediterranean and the Red Sea, which would have led to considerable losses for the British economy. Furthermore, a successful invasion of Egypt could have been followed by a direct attack on British territory in India. After France and Spain allied with each other in 1796, the Royal Navy was forced to withdraw from the Mediterranean in 1798.[11][12] He further wished to strengthen French trade interests over those of Great Britain in the Middle East, hoping to join forces with France's ally Tipu Sultan, ruler of Mysore in India and an opponent of British control in that country.[13]

For reasons of secrecy, the president of the directorate wrote the order to Napoleon himself. It was stated that the expedition was to consist of 36,000 men from the old Italian army, officers and generals of his choice, various scientists and craftsmen. The Treasury was instructed to send Napoleon 1.5 million francs every decade. In addition, he was authorised to take 3 of the 8 million francs from the 'Bernese treasury', which France had had paid to it by the defeated Confederation for its military intervention to establish a Helvetic Republic[14] In March 1798, the Directory took the official decision to launch the expedition to Egypt and appointed Bonaparte commander-in-chief of the Armée d'Orient. Bonaparte was tasked with first occupying Malta and then moving on to the conquest of Egypt. Once the occupation of Egypt was complete, he was to establish communications with India and secure the Red Sea, which in turn would facilitate the expulsion of the British from the Orient and a future French expedition to India.[6]

Preparations

[edit]Preparations for the expedition were spread across Toulon, Marseille, Genoa, Corsica and Civitavecchia and were essentially organised by Napoleon's chief of staff Louis Berthier. Around 300 ships were requisitioned for the transport. The escort was provided by 13 ships of the line and the same number of frigates under François-Paul Brueys d'Aigalliers. By 11 May, the Orient army had grown to 30,800 infantrymen, 3,475 cavalrymen, 1,660 artillerymen, 60 field guns and 40 siege guns Including all civilians (artists and researchers), the total number was 38,000.[15] To prevent news of the impending attack on Egypt from spreading before the fleet arrived, all merchant ships that sighted the convoy during the crossing were to be seized and detained until the French had reached Alexandria[16].

Expedition

[edit]On 19 May, Napoleon gave the order on board the flagship L'Orient to set sail from Toulon with his invasion fleet. The fleet sailed along the coast of Provence towards Genoa and from there southwards to Corsica. Until 30 May, the fleet remained within sight of the east coast, crossed the Strait of Bonifacio and then followed the coast of Sardinia with the intention of joining up with the ships coming from Civitavecchia. On 3 June, Napoleon received news of the British presence in Sardinia, whereupon he sent a squadron to reconnoitre the situation. However, after the British were not encountered, Napoleon gave the order to stop waiting for the ships from Civitavecchia and had his fleet turn south-east, passing Mazara del Vallo and Pantelleria on 7 June. There Napoleon learned that he was being pursued by the British, whereupon he set course for Malta, which he reached on 9 June and joined up with the 56 ships from Civitavecchia. The French expeditionary force was thus complete and set course for Sicily. It rounded the southern tip of Sardinia as early as 5 June[17][18].

Capture of Malta

[edit]When Napoleon's fleet arrived off Malta, Napoleon demanded that the Knights of Malta allow his fleet to enter the port and take on water and supplies. Grand Master von Hompesch replied that only two foreign ships would be allowed to enter the port at a time. Under that restriction, re-victualling the French fleet would take weeks, and it would be vulnerable to the British fleet of Admiral Nelson. Napoleon therefore ordered the invasion of Malta. The French Revolution had significantly reduced the Knights' income and their ability to put up serious resistance. Half of the Knights were French, and most of these knights refused to fight.[19] Thus Malta was conquered without much resistance.[20][21]

Alexandria to Syria

[edit]Disembarkment at Alexandria

[edit]

Napoleon departed Malta for Egypt. After successfully eluding detection by the Royal Navy for thirteen days, the fleet was in sight of Alexandria where it landed on 1 July, although Napoleon's plan had been to land elsewhere.

On the day of the landing, Napoleon told his troops I promise to each soldier who returns from this expedition, enough to purchase six arpents of land.

(approximately 7.6 acres or 3.1 ha) and added:

The peoples we will be living alongside are Muslims; their first article of faith is There is no other god but God, and Mahomet is his prophet

. Do not contradict them; treat them as you treated the Jews, the Italians; respect their muftis and their imams, as you respected their rabbis and bishops. Have the same tolerance for the ceremonies prescribed by the Quran, for their mosques, as you had for the convents, for the synagogues, for the religion of Moses and that of Jesus Christ. The Roman legions used to protect all religions. You will here find different customs to those of Europe, you must get accustomed to them. The people among whom we are going treat women differently to us; but in every country whoever violates one is a monster. Pillaging only enriches a small number of men; it dishonours us, it destroys our resources; it makes enemies of the people who it is in our interest to have as our friends. The first city we will encounter was built by Alexander [the Great]. We shall find at every step great remains worthy of exciting French emulation.[22]

Despite the idealistic promises proclaimed by Napoleon, Egyptian intellectuals like 'Abd al-Rahman al-Jabarti (1753–1825 C.E/ 1166–1240 A.H) were heavily critical of Napoleon's objectives. As a major chronicler of the French invasion, Jabarti decried the French invasion of Egypt as the start of:>"fierce fights and important incidents; of the momentous mishaps and appalling afflictions, of the multiplication of malice and the acceleration of affairs; of successive sufferings and turning times; of the inversion of the innate and the elimination of the established; of horrors upon horrors and contradicting conditions; of the perversion of all precepts and the onset of annihilation; of the dominance of destruction and the occurrence of occasions"[23]

Menou had been the first to set out for Egypt, and was the first Frenchman to land. Bonaparte and Kléber landed together and joined Menou at night at the cove of Marabout (Citadel of Qaitbay), on which the first French tricolour to be hoisted in Egypt was raised. On the night of the 1st of July, Bonaparte who was informed that Alexandria intended to resist him, rushed to get a force ashore without waiting for the artillery or the cavalry to land, in which he marched on Alexandria at the head of 4,000 to 5,000 men.[24] At 2 am, 2 July, he set off marching in three columns, on the left, Menou attacked the "triangular fort", where he received seven wounds, while Kléber was in the centre, in which he received a bullet in the forehead but was only wounded, and Louis André Bon on the right attacked the city gates.[25] Alexandria was defended by Koraim Pasha and 500 men.[26] However, after a rather lively shooting in the city, the defenders gave up and fled.[27]

Victory on land, defeat at sea

[edit]Once all the troops were ashore by 3 July, Napoleon made arrangements to leave the delta and capture Cairo, the capital of Egypt. A flotilla, loaded with provisions, cannons, ammunition and equipment, was to sail along the coast to the mouth of the Rosetta, head for the Nile and follow the army upstream from Rahmaniyyah. In order to reach Cairo before the annual flooding of the Nile, Napoleon decided to march his troops the 72 kilometres to Rahmaniyyah through the desert. When the French set off for Cairo on 6 July, the soldiers were still wearing thick woollen uniforms and their knapsacks were packed full of equipment, with the exception of water bottles. Many suffered from dysentery or eye inflammation, others were so desperate that they committed suicide. The villages marked on the maps turned out to be mostly deserted and the wells had been filled in by hostile Bedouins.[27]

Battle of the Pyramids

[edit]

On 20 July, the French army had advanced as far as Umm Dinar, 29 km north of Cairo. Observers reported that an Egyptian force under Murad Bey had gathered on the west bank of the Nile at Imbāba. Other Egyptian troops under Ibrahim Bey were on the east bank of the Nile. After Napoleon had reached the battlefield, the 6,000-strong Mamluk cavalry attacked the French at around 3.30 pm. Formed into squares, the French were able to fend off the cavalry attacks and finally counter-attack and put the Mamluks to flight. Murad withdrew with the remnants of his troops to Upper Egypt and Ibrahim, in the direction of Belbeys, in order to retreat to Syria. The battle cost the French barely a hundred dead and wounded, while the Mamluks suffered around 1,500 dead and wounded[28]. In two proclamations to the Egyptians and the inhabitants of Cairo, Napoleon declared that the aim of the French invasion was to liberate the country from the slavery and exploitation of the Mamluk 'clan' (race) and their autocratic beys. The inhabitants, their families, their houses and property would be protected. Their way of life and religion would be respected, and dīwāne would be established for self-government, staffed by local dignitaries[29]

Dupuy's brigade pursued the routed enemy and at night entered Cairo, which had been abandoned by the beys Mourad and Ibrahim. On 4 Thermidor (22 July), the notables of Cairo came to Giza to meet Bonaparte and offered to hand over the city to him. Three days later, he moved his main headquarters there. Desaix was ordered to follow Mourad, who had set off for Upper Egypt. An observation corps was put in place at Elkanka to keep an eye on the movements of Ibrahim, who was heading towards Syria. Bonaparte personally led the pursuit of Ibrahim, beat him at Salahie and pushed him completely out of Egypt.

Battle of the Nile

[edit]On 1 August, the British Mediterranean fleet under Horatio Nelson discovered the French fleet under François-Paul Brueys d'Aigalliers anchored in the shallows of the Bay of Abukir near Alexandria. The French were initially unperturbed, as they assumed that the British would not begin their attack until the following morning. However, the British were determined to begin the attack that very night. The French had made a mistake and left a gap in their defence. The British ships were able to penetrate this gap and fire on the French ships from two sides. At around 10 pm, the French flagship L'Orient exploded. The battle continued into the night and only two of Brueys' ships of the line and two French frigates escaped destruction or capture by the British.[30]

News of the naval defeat reached Bonaparte en route back to Cairo from defeating Ibrahim but, far from being worried, Mullié states: This disastrous event did not disconcert [Bonaparte] at all – ever impenetrable, he did not allow any emotion to appear that he had not tested in his mind. Having calmly read the despatch which informed him that he and his army were now prisoners in Egypt, he said We no longer have a navy. Well! We'll have to stay here, or leave as great men just as the ancients did

. The army then showed itself happy at this short energetic response, but the native Egyptians considered the defeat at Aboukir as fortune turning in their favour and so from then on busied themselves to find means to throw off the hateful yoke the foreigners were trying to impose on them by force and to hunt them from their country. This project was soon put into execution.[31]

After the Battle of Pyramids, Napoleon instituted a French administration in Cairo and suppressed the subsequent rebellions violently. Although Napoleon tried to co-opt local Egyptian ulema, scholars like Al-Jabarti poured scorn on the ideas and cultural ways of the French.[32]Despite their cordial proclamations to the natives, with some French soldiers even converting to Islam, clerics like Abdullah al-Sharqawi condemned the French as: materialist, libertine philosophers ... they deny the Resurrection, and the afterlife, and ... [the] prophets[33]

Bonaparte's administration of Egypt

[edit]

After the naval defeat at Aboukir, Bonaparte's campaign remained land-bound. His army still succeeded in consolidating power in Egypt, although it faced repeated nationalist uprisings, and Napoleon began to behave as absolute ruler of all Egypt. He set up a pavilion and from within it presided over a fête du Nil—it was he who gave the signal to throw into the floats the statue of the river's fiancée, his name and Mohammed's were mingled in the same acclamations, on his orders gifts were distributed to the people, and he gave kaftans to his main officers.

In a largely unsuccessful effort to gain the support of the Egyptian population, Bonaparte issued proclamations that cast him as a liberator of the people from Ottoman and Mamluk oppression, praising the precepts of Islam and claiming friendship between France and the Ottoman Empire despite French intervention in the breakaway state. This position as a liberator initially gained him solid support in Egypt and later led to admiration for Napoleon from the Albanian Muhammad Ali of Egypt, who succeeded where Bonaparte had not in reforming Egypt and declaring its independence from the Ottomans. In a letter to a sheikh in August, Napoleon wrote, I hope... I shall be able to unite all the wise and educated men of all the countries and establish a uniform regime based on the principles of the Quran which alone are true and which alone can lead men to happiness.

[34]

Shortly after Bonaparte's return from facing Ibrahim came Mohammed's birthday, which was celebrated with great pomp. Bonaparte himself directed the military parades for the occasion, preparing for this festival in the sheik's house wearing oriental dress and a turban. It was on this occasion that the divan granted him the title Ali-Bonaparte after Bonaparte proclaimed himself a worthy son of the Prophet

and favourite of Allah

. Around the same time he took severe measures to protect pilgrim caravans from Egypt to Mecca, writing a letter himself to the governor of Mecca.

Even so, thanks to the taxes he imposed on them to support his army, the Egyptians remained unconvinced of the sincerity of all Bonaparte's attempts at conciliation and continued to attack him ceaselessly. Any means, even sudden attacks and assassination, were allowed to force the "infidels" out of Egypt. Military executions were unable to deter these attacks and they continued.

22 September was the anniversary of the founding of the First French Republic and Bonaparte organised the most magnificent celebration possible. On his orders, an immense circus was built in the largest square in Cairo, with 105 columns (each with a flag bearing the name of a département) round the edge and a colossal inscribed obelisk at the centre. On seven classical altars were inscribed the names of heroes killed in the French Revolutionary Wars. Two triumphal arches were built to commemorate the campaign: a wooden arc de triomphe in Azbakiyya Square, and a second arch which was inscribed with the words There is no god but God, and Muhammad is his prophet

and decorated by the Genoese artist Michel Rigo with scenes from the Battle of the Pyramids.[35] Here there was some awkwardness – the painting flattered the French but aggrieved the defeated Egyptians they were trying to win over as allies.

On the day of the festival, Bonaparte addressed his troops, enumerating their exploits since the 1793 siege of Toulon and telling them: >From the English, famous for arts and commerce, to the hideous and fierce Bedouin, you have caught the gaze of the world. Soldiers, your destiny is fair... This day, 40 million citizens celebrate the era of representative government, 40 million citizens think of you. The speech was followed by cries of "Vive la République!" and a cannon volley. Later, Bonaparte held a feast for two hundred people in a garden in Cairo and sent soldiers to plant a French flag on the top of a pyramid.[36]

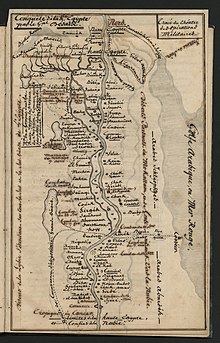

Pursuit of Mamluks

[edit]After his defeat at the Pyramids, Mourad Bey retreated to Upper Egypt. On 25 August 1798, General Desaix embarked at the head of his division on a flotilla and sailed up the Nile.[37] On 31 August, Desaix arrived at Beni Suef where he began to encounter supply problems, then he went up the Nile to Behneseh and progressed towards Minya. The Mamluks did not fight, and the flotilla returned on September 12 at the entrance of Bahr Yussef. Desaix learned that the Mamluks were in the plain of Faiyum by 24 September. The first contact between the two sides occurred on 3 October and a second minor fight took place, which began to deplete food and ammunition of the French forces. On 7 October, Mourad Bey's troops came out of Sédiman's entrenchments and attacked the French, who formed themselves into three squares, one large and two small at its angles.[38] The Mamluks as previous encounters attacked furiously but were repulsed.The Mamluks attempted to use their four cannons, but a vigorous attack led by Captain Jean Rapp managed to capture them.[39]

Bedouin Insurgency

[edit]Napoleon faced a Bedouin insurgency that formed in Bedouin camps in the barren deserts near the Nile and later in Arabia. Bedouin tribes, traditionally nomadic inhabitants of the arid landscapes, successfully disrupted French logistics and conducting successful raids against French forces and nearby French garrisons. As the French army advanced through the Egyptian and Syrian territories, it encountered resistance from Bedouin tribes that sought to defend their local encampments and resist foreign occupation. The vast and harsh desert terrain provided the Bedouin with a natural advantage, allowing them to launch hit-and-run attacks on French supply lines and communication routes. These raids not only disrupted the logistical operations of the French forces but also created a need for local garrisons and convoys for French logistical lines which siphoned manpower. The Bedouin tribes, having far superior knowledge of the desert and hit-and-run tactics, capitalized on their familiarity with the terrain to evade the more conventionally organized French military. Utilizing their mobility and mastery of desert navigation, the Bedouin struck swiftly and retreated into the vast expanses, making it challenging for the French to pursue and engage them in a conventional battle. The insurgency reached its peak in 1799, during which Bedouin tribes formed loose alliances to coordinate attacks on French outposts, supply caravans, and vulnerable positions. These coordinated efforts were instrumental in sowing discord among the French ranks and hindering their ability to consolidate control over the region. While the Bedouin insurgency was primarily characterized by hit-and-run tactics, there were instances where the tribes managed to score significant victories against the French. Successful ambushes and surprise attacks not only inflicted casualties on the occupiers but also undermined the morale of French forces along with undermining the security of French lines, contributing to the overall difficulty of maintaining control over the deserts. Despite the constant attacks by Bedouin tribes, the French ultimately maintained control in urban centers. However, the constant pressure from the Bedouin and the logistical strain caused by their raids contributed to the overall difficulties faced by the French Army.

Revolt of Cairo

[edit]

In 1798, Napoleon led the French army into Egypt, swiftly conquering Alexandria and Cairo. However, in October of that year, discontent against the French led to an uprising by the people of Cairo. While Bonaparte was in Old Cairo, the city's population began spreading weapons around to one another and fortifying strongpoints, especially at the Al-Azhar Mosque. A French commander, Dominique Dupuy, was killed by the revolting Cairenes, as well as Bonaparte's Aide-de-camp, Joseph Sulkowski. Excited by the sheikhs and imams, the local citizens swore by the Prophet to exterminate all and any Frenchman they met, and all Frenchmen they encountered – at home or in the streets – were mercilessly slaughtered. Crowds rallied at the city gates to keep out Bonaparte, who was repulsed and forced to take a detour to get in via the Boulaq gate.

The French army's situation was critical – the British were threatening French control of Egypt after their victory at the Battle of the Nile, Murad Bey and his army were still in the field in Upper Egypt, and the generals Menou and Dugua were only just able to maintain control of Lower Egypt. The Ottoman peasants had common cause with those rising against the French in Cairo – the whole region was in revolt.

The French responded by setting up cannons in the Citadel and firing them at areas containing rebel forces. During the night, French soldiers advanced around Cairo and destroyed any barricades and fortifications they came across. The rebels soon began to be pushed back by the strength of the French forces, gradually losing control of their areas of the city. Bonaparte personally hunted down rebels from street to street and forced them to seek refuge in the Al-Azhar Mosque. Bonaparte said that He [i.e God] is too late – you've begun, now I will finish!

. He then immediately ordered his cannon to open fire on the Mosque. The French broke down the gates and stormed into the building, massacring the inhabitants. At the end of the revolt 5,000 to 6,000 Cairenes were dead or wounded.[40]

Syria

[edit]Canal of the Pharaohs

[edit]With Egypt quiet again and under his control, Bonaparte used this time of rest to visit Suez and see with his own eyes the possibility of a canal (known as the Canal of the Pharaohs) said to have been cut in antiquity between the Red Sea and the Nile by order of the pharaohs. Before setting out on the expedition, he gave Cairo back its self-government as a token of its pardon – a new 'divan' made up of 60 members replaced the military commission. Then, accompanied by his colleagues from the Institut, Berthollet, Monge, Le Père, Dutertre, Costaz, Caffarelli, and followed by a 300-man escort, Bonaparte set out for the Red Sea and after three days' marching across the desert he and his caravan arrived at Suez. After giving orders to complete the fortifications at Suez, Bonaparte crossed the Red Sea and on 28 December moved into Sinai to look for the celebrated mountains of Moses 17 kilometres from Suez. On his return, surprised by the rising tide, he ran the risk of drowning. Arriving back at Suez, after much exploration the expedition fulfilled its aim, finding the remains of the ancient canal built by Senusret III and Necho II.

Ottoman offensives

[edit]

In the meantime the Ottomans in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) received news of the French fleet's destruction at Aboukir and believed this spelled the end for Bonaparte and his expedition, trapped in Egypt. Sultan Selim III decided to wage war against France, and sent two armies to Egypt. The first army, under the command of Jezzar Pasha, had set out with 12,000 soldiers; but was reinforced with troops from Damascus, Aleppo, Iraq (10,000 men), and Jerusalem (8,000 men). The second army, under the command of Mustafa Pasha, began on Rhodes with about eight thousand soldiers. He also knew he would get about 42,000 soldiers from Albania, Constantinople, Asia Minor, and Greece. The Ottomans planned two offensives against Cairo: from Syria, across the desert of El Salheya-Bilbeis-Al Khankah, and from Rhodes by sea landing in the Aboukir area or the port city of Damietta.

French response

[edit]At the end of 1798, the most pressing problem was the rapid build-up of Ottoman troops, which the Sultan had planned for a massive attack on Egypt. One was the Rhodes army, which was transported by sea with the help of the Royal Navy. The other, the Damascus Army, advanced on Egypt via Palestine and the Sinai. While these moves were being prepared, Ahmed Pasha al-Jazzar was to advance from Acre on the Egyptian border and attract Napoleon's attention. In this precarious situation, Napoleon decided to pre-empt the attack, capture Acre, defeat the Ottomans in Syria and then return to Egypt to confront them. He prepared around 14,000 soldiers who were organised in divisions under the command of Generals Reynier Kléber, Bon, Lannes, a cavalry division under General Murat, a brigade of infantry and cavalry under Brigade chief Bessières, a camel company, artillery under Dommartin, and engineers and sappers under Caffarelli. The heavy siege artillery pieces were sent by the flotilla under contre-amiral Perrée to Jaffa.On 10 February 1799, Napoleon left Cairo for Syria. His first target was El-Arish, which finally surrendered on 19 February after an unexpected siege. Gaza fell without resistance on 25 February, and by 3 March the French had reached the outskirts of Jaffa.[41]

Jaffa

[edit]This city was surrounded by high walls flanked by towers. Jezzar had entrusted its defence to elite troops, with the artillery manned by 1,200 Ottoman gunners. The city was one of the ways into Syria, its port could be used by his fleet and a large part of the expedition's success depended on its fall. This meant Bonaparte had to capture the city before advancing further, and so he laid siege to it. Following the successful assault on the 7th of March, the city surrendered. A French officer's subordinate successfully persuaded three thousand Turks in the citadel of Jaffa that they would be granted amnesty. However, Bonaparte ordered the execution of every man and of a further 1,400 prisoners. He later attempted to justify this action by claiming it was a military necessity, as he had no food for so many prisoners, could not spare them an escort, and had found paroled Turks from El Arish serving in the garrison. However, none of these explanations have survived scrutiny.[42][43]

Acre

[edit]The initial successes ended before the city of Acre. With the support of the British, who reached Acre on 15 March, the city's defences were strengthened. In addition, the Royal Navy managed to muster the French flotilla transporting the ammunition and cannons[44] Without his siege guns, Napoleon had to resort to more time-consuming methods of besieging the city. Meanwhile, the Damascus Army was on its way to lay siege to Acre. Upon establishing contact with the opposing forces, the French forces demonstrated clear superiority in the initial stages of engagement. On 8 April, a Junot officer emerged victorious in a cavalry skirmish near Nazareth, despite being outnumbered. This was followed by a significant victory on 11 April, where Kléber, leading 1,500 men, routed a substantial force of 6,000 Turks in a battle at Canaan. In another engagement, the dashing cavalry leader Joachim Murat successfully led his troops across the Jordan to the north of Lake Tiberia, engaging and defeating 5,000 Turks.[45]

Mount Tabor

[edit]

After sixty days' repeated attacks and two murderous and inconclusive assaults, the city remained uncaptured. Even so, it was still awaiting reinforcements by sea as well as a large army forming up in Asia on the sultan's orders to march against the French. To find out the latter's movements, Jezzar ordered a general sortie against Bonaparte's camp. This sortie was supported by its own artillery and a naval bombardment from the British. With his usual impetuosity, Bonaparte pushed Jezzar's columns back against their own walls and then went to help Kléber, who was retrenched in the ruins with 4,000 Frenchmen under his command against 20,000 Ottomans at Mount Tabor. Bonaparte conceived a trick which used all the advantages offered him by the enemy position, sending Murat and his cavalry across the River Jordan to defend the river crossing and Vial and Rampon to march on Nablus, while Bonaparte himself put his troops between the Ottomans and the magazines. These manoeuvres were successful, in what was known as the Battle of Mount Tabor. The enemy army, taken by surprise at many points at once, was routed and forced to retreat, leaving their camels, tents, provisions and 5,000 dead on the battlefield.[45]

Returning to besiege Acre, Bonaparte learned that Rear-Admiral Perrée had landed seven siege artillery pieces at Jaffa. Bonaparte then ordered two assaults, both vigorously repulsed. A fleet was sighted flying the Ottoman flag and Bonaparte realised he must capture the city before that fleet arrived with reinforcements. A fifth general attack was ordered, which took the outer works, planted the French tricolour on the rampart, pushed the Ottomans back into the city and forced the Ottoman fire to relent. Acre was thus taken or about to capitulate.

One of those fighting on the Ottoman side was the French émigré and engineer officer Phélippeaux, one of Bonaparte's classmates at the École Militaire. Phélippeaux ordered cannon to be placed in the most advantageous positions and new trenches dug as if by magic behind the ruins which Bonaparte's forces had captured. At the same time Sidney Smith, commander of the British fleet, and his ships' crews landed. These factors renewed the courage of the besieged and they pushed Bonaparte's force back, with stubborn fury on both sides. Faced with heavy losses in the battles around Acre, an outbreak of plague among his soldiers and the hardships caused by the heat, Napoleon after 63 days of campaigning finally had to retreat to Egypt.[46]

Retreat from Acre

[edit]The French force's situation was now critical – the enemy could harass its rear as it retreated, it was tired and hungry in the desert, and it was carrying a large number of plague-sufferers. To carry these sufferers in the middle of the army would spread the disease, so they had to be carried in the rear, where they were most at risk from the fury of the Ottomans, keen to avenge the massacres at Jaffa. There were two hospital depots, one in the large hospital on Mount Carmel and the other at Jaffa. On Bonaparte's orders, all those at Mount Carmel were evacuated to Jaffa and Tantura. The gun horses were abandoned before Acre and Bonaparte and all his officers handed their horses over to the transport officer Daure, with Bonaparte walking to set an example.

To conceal its withdrawal from the siege, the army set off at night. Arriving at Jaffa, Bonaparte ordered three evacuations of the plague sufferers to three different points – one by sea to Damietta, one by land to Gaza and another by land to Arish. During the retreat the army picked clean all the lands through which they passed, with livestock, crops and houses all being destroyed. Gaza was the only place to be spared, in return for remaining loyal to Bonaparte. To speed the retreat, Napoleon suggested the controversial step of euthanizing his own soldiers who were terminally ill with plague (between 15 and 50, sources vary) and not expected to recover through an opium overdose, to relieve their suffering, ease the retreat, prevent the spread of the disease and prevent the torture and executions the soldiers left behind would have received if captured by the enemy; his doctors refused to carry out such orders[47][48][49] but there is also evidence in the form of first-hand testimonies that claim the mass euthanasia did take place, and the matter remains one for debate.[50][51]

Back in Egypt

[edit]Upon his return to Cairo, Napoleon made plans for departure. In an effort to exert pressure on the Directory to recall him, he sent a dispatch to Paris on 29 June, acknowledging the loss of 5,344 men and requesting 6,000 reinforcements, despite being well aware that they would not be forthcoming. On 11 August, Napoleon received word of the crisis in Europe. France was facing a coalition of England, Austria, Russia, Turkey and Naples. An Anglo-Russian army had invaded Holland and an Austro-Russian army had gained control of Switzerland; a Turco-Russian fleet had captured Corfu; and another Austro-Russian army had advanced into northern Italy undoing all of Bonaparte's work in a matter of weeks. France was reported to be on the verge of economic collapse, and royalist sentiment was running high.[52]

Campaigns in Upper Egypt

[edit]The French were determined to exterminate the Mamluks or to expel them from Egypt. By that time, the Mamluks were driven out of Faiyum to Upper Egypt. General Desaix informed Bonaparte of his situation, and soon received a reinforcement of 1,000 cavalry and three light artillery pieces, commanded by General Davout. On 29 December 1798, the French army arrived at Girga, capital of Upper Egypt, and waited there for a flotilla to bring them ammunition. However, twenty days passed without hearing of the flotilla. In the meantime, Mourad Bey had contacted chieftains from Jeddah and Yanbu to cross the Red Sea and to exterminate a handful of infidels who have come to destroy the religion of Mohammed. He also sent emissaries to Nubia to bring reinforcements, and Hassan Bey Jeddaoui who also conjured to join against the enemies of the Quran.

Upon hearing these endeavours, General Davout mobilized his forces on 2–3 January 1799, where he met a multitude of armed men near the village of Sawaqui.[53] The insurgents were easily routed, and eight hundred of them remained on the battlefield. However, the locals kept gathering around Asyut to combat the French. On 8 January, Davout met another local forces at Tahta, where he killed a thousand men and put the rest to flight.[54] In the meantime, Mourad Bey's army was reinforced by a thousand sheriffs arriving from beyond the Red Sea, two hundred and fifty Mamluks led Hassan bey Jeddaoui and Osman bey Hassan, in addition to Nubians and North Africans led by Sheikh Al-Kilani, where they encamped near the village of Houé, all supported by the inhabitants of Upper Egypt and the Cataracts of the Nile.[54]

Battle of Samhud

[edit]The combined Muslim army marched on 21 January 1799 in the desert, until they reached Samhud near Qena. On 22 January, Desaix formed three squares, two infantry and one cavalry. The latter was placed in the centre of the other two, in order to be protected. The French were scarcely drawn up in line, as the enemy cavalry completely surrounded them, while a column of Arabs from Yanbu fired continuously on their left. Desaix instructed the riflemen of the 96th Infantry Regiment to attack them, while Rapp and Savary, at the head of a squadron of cavalry, would charge the enemy in flank.[55]

The Arabs were attacked so vividly which forced them to flee, leaving about thirty of their own in the square, both killed and wounded. Afterwards, the Arabs of Yanbu, having rallied, came back to attack, and wanted to capture the village of Samhud, but the riflemen of the 96th Infantry Regiment assaulted them viciously and directed against them such a sustained fire, in which they were obliged to withdraw, after having lost many people.[55]

However, the numerous Muslim forces were advancing, uttering frightful cries, and the Mamluks swooped down on the squares commanded by the generals, Friant and Belliard, but they were so strongly repulsed by artillery and musketry fire that they had to withdraw, leaving the battlefield strewn with their dead.[55] Mourad Bey and Osman bey Hassan, who commanded the Mamluk corps, could not stand against the charge of Davout's cavalry. They abandoned their positions, and dragged the whole army in their flight. The French pursued their enemies until the next day, and did not stop until after having pushed them beyond the Cataracts of the Nile.[55]

Battle of Aswan

[edit]Desaix continued to march south, as he reached Esneh on 9 February. Meanwhile, Osman bey Hassan had stationed his forces at the foot of a mountain near Aswan. On 12 February, General Davout discovered the enemy positions and immediately made his military arrangements. He formed his cavalry in two lines, and, in this order of battle, he swooped down on the Mamluks. Osman bey Hassan was dangerously wounded, as he saw his horse killed under him. The French cavalry rushed with such impetuosity on the Ottomans, and the fight turned into fury. However, the Mamluks were defeated and forced to abandon the battlefield.[56]

Massacre of Qena

[edit]By the end of February 1799, Sherif Hassan and 2,000 Infantry arrived from Mecca. When Desaix and his forces reached Asyut, his flotilla was left behind near Qena. On 3 March, Ottomans launched an attack on the flotilla which was called "L' Italie" led by Captain Morandi with 200 marines and 300 wounded and blind on board. Morandi tried to manoeuvre but the vessel was boarded by hundreds of invaders, in which he ordered that the vessel to be set on fire. He was later killed by rain of hostile bullets. However, all on board were eventually mutilated and killed.[57]

Battle of Abnud

[edit]On 8 March 1799, General Belliard led his forces to fight 3,000 Meccan Infantry and 350 Mamluks in the plain of Abnud, located on the right bank of the Nile to the south of Qena. The French with their square formation managed to advance on the Ottoman forces who later garrisoned themselves in the houses of Abnud. The fighting lasted for hours, afterward, the French managed to reach the courtyard of the village and set the houses on fire. The Ottomans were forced to escape and the remaining injured were all killed.[58]

Battle of Beni Adi

[edit]The Mamluks maintained with their strategy of inciting the locals against the French forces. On 1 May 1799, General Davout's forces killed at least 2,000 fellahin at Beni Adi near Asyut.[59] However, as they were pursuing Murad Bey into Upper Egypt, the French discovered the monuments at Dendera, Thebes, Edfu and Philae.

Capture of Kosseir

[edit]On 29 May 1799, General Belliard managed to capture Kosseir on the Red Sea, after he marched through the desert, to halt further incoming of Meccan troops or any possible invasion from the English.[60]

Abukir to withdrawal

[edit]Battle of Abukir

[edit]At Cairo the army found the rest and supplies it needed to recover, but its stay there could not be a long one. Bonaparte had been informed that Murad Bey had evaded the pursuit by Generals Desaix, Belliard, Donzelot and Davout and was descending on Lower Egypt. Bonaparte thus marched to attack him at Giza, also learning that 100 Ottoman ships were off Aboukir, threatening Alexandria.

Without losing time or returning to Cairo, Bonaparte ordered his generals to make all speed to meet the army commanded by the pasha of Rumelia, Saïd-Mustapha, which had joined up with the forces under Murad Bey and Ibrahim. Before leaving Giza, where he found them, Bonaparte wrote to Cairo's divan, stating: Eighty ships have dared to attack Alexandria but, beaten back by the artillery in that place, they have gone to anchor in Aboukir Bay, where they began disembarking [troops]. I leave them to do this, since my intention is to attack them, to kill all those who do not wish to surrender, and to leave others alive to be led in triumph to Cairo. This will be a handsome spectacle for the city.

The Ottoman troops, led by Mustafa Pasha, entrenched themselves in a heavily fortified position near the coast at Abukir. On 25 June 1799, Napoleon attacked the Ottoman forces, which consisted of around 18,000 soldiers, with around 10,000 French troops. The French infantry fought their way through three successive lines of Turkish entrenchments, greatly assisted by the stupidity of the Janissaries who repeatedly left their positions in search of French heads, but the coup de grdce was delivered by Murat at the head of his cavalry shortly after midday. The dashing Gascon found the knowledge of the ground acquired the previous July of the greatest assistance, and the Turks were swept back by the ferocity of his charge; after a fierce struggle, in which Murat personally engaged the enemy general and was wounded in the cheek, the Turkish headquarters was captured together with many senior enemy officers.[61]

Bonaparte leaves Egypt

[edit]The land battle at Abukir was Bonaparte's last action in Egypt, partly restoring his reputation after the French naval defeat at the same place a year earlier. During the prisoner exchange at Aboukir and notably via the Gazette de Francfort Sidney Smith had sent him, he was in communication with the British fleet, from which he had learned of events in France. As Bonaparte saw (and later mythologised) France was thrown back into retreat, its enemies had recaptured France's conquests, France was unhappy at its dictatorial government and was nostalgic for the glorious peace it had signed in the Treaty of Campo Formio – as Bonaparte saw it, this meant France needed him and would welcome him back. With the Egyptian campaign stagnating and political instability developing back home, a new phase in Bonaparte's career was beginning – he felt that he had nothing left to do in Egypt which was worthy of his ambition and that (as had been shown by the defeat at Acre) the forces he had left to him there were not sufficient for an expedition of any importance outside of Egypt. Bonaparte thus spontaneously decided to return to France.[62]

He only shared the secret of his return with a small number of friends whose discretion and loyalty were well-known. He left Cairo in August on the pretext of a voyage in the Nile Delta without arousing suspicion, accompanied by the scholars Monge and Berthollet, the painter Denon, and generals Berthier, Murat, Lannes and a handfull of other officers including Marmont, Andréossy and Bessières.[63] On 23 August, a proclamation informed the army that Bonaparte had transferred his powers as commander in chief to General Kléber. Kleber read to his troops the concise communiqué Napoleon had left: 'Only extraordinary circumstances have persuaded me, for the benefit of my country and its reputation and in obedience, to pass through the enemy lines and return to Europe.[64]

End of the campaign

[edit]

The troops Bonaparte left behind were supposed to be honourably evacuated under the terms of the Convention of El Arish Kléber had negotiated with Smith and the Ottoman commander Kör Yusuf in early 1800, but Britain refused to sign and Kör Yusuf sent an amphibious assault force of 30,000 Mamlukes against Kléber.

Kléber defeated the Mamlukes at the battle of Heliopolis in March 1800, and then suppressed an insurrection in Cairo. On 14 June (26 prairial), a Syrian student called Suleiman al-Halabi assassinated Kléber with a dagger in the heart, chest, left forearm and right thigh. Command of the French army passed to General Menou, who held command from 3 July until August 1801. Menou's letter was published in Le Moniteur on 6 September, with the conclusions of the committee charged with judging those responsible for the assassination: The committee, after carrying through the trial with all due solemnity and process, thought it necessary to follow Egyptian customs in its application of punishment; it condemned the assassin to be impaled after having his right hand burned; and three of the guilty sheikhs to be beheaded and their bodies burned.

The Anglo-Ottomans then commenced their land offensive, the French were defeated by the British in the Battle of Alexandria on March 21, surrendered at Fort Julien in April and then Cairo fell in June. Finally besieged in Alexandria from 17 August – 2 September, Menou eventually capitulated to the British. Under the terms of his capitulation, the British General John Hely-Hutchinson allowed the French army to be repatriated in British ships. Menou also signed over to Britain all Egyptian antiquities, such as the Rosetta Stone, which the French had collected. After initial talks in Al Arish on 30 January 1802, the Treaty of Paris on 25 June ended all hostilities between France and the Ottoman Empire, returning Egypt to the Ottomans.[65]

Scientific expedition

[edit]

An unusual aspect of the Egyptian expedition was the inclusion of an enormous contingent of scientists and scholars ("savants") assigned to the invading French force, 167 in total. This deployment of intellectual resources is considered as an indication of Napoleon's devotion to the principles of the Enlightenment, and by others as a masterstroke of propaganda obfuscating the true motives of the invasion: the increase of Bonaparte's power.

These scholars included engineers and artists, members of the Commission des Sciences et des Arts, the geologist Dolomieu, Henri-Joseph Redouté, the mathematician Gaspard Monge (a founding member of the École polytechnique), the chemist Claude Louis Berthollet, Vivant Denon, the mathematician Jean-Joseph Fourier (who did some of the empirical work upon which his analytical theory of heat

was founded in Egypt), the physicist Étienne Malus, the naturalist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, the botanist Alire Raffeneau-Delile, and the engineer Nicolas-Jacques Conté of the Conservatoire national des arts et métiers.

Their original aim was to help the army, notably by opening a Suez Canal, mapping out roads and building mills to supply food. They founded the Institut d'Égypte with the aim of propagating Enlightenment values in Egypt through interdisciplinary work, including improving its agricultural and architectural techniques. A scientific review was created under the title Décade égyptienne and in the course of the expedition the scholars also observed and drew the flora and fauna in Egypt and became interested in the country's resources. The Egyptian Institute saw the construction of laboratories, libraries, and a printing press. The group worked prodigiously, and some of their discoveries were not finally cataloged until the 1820s.[66] A young engineering officer, Pierre-François Bouchard, discovered the Rosetta Stone in July 1799. Many of the antiquities discovered by the French in Egypt, including the stone, were signed over to the British at the end of the campaign by Menou as part of his treaty with Hutchinson. The French scholars' research in Egypt gave rise to the 4-volume Mémoires sur l'Égypte (published from 1798 to 1801). A subsequent and more comprehensive text was Description de l'Égypte, published on Napoleon's orders between 1809 and 1821. Publications such as these of Napoleon's discoveries in Egypt gave rise to fascination with Ancient Egyptian culture and the birth of Egyptology in Europe.

The scientists also tested methods in hot air ballooning while in Egypt. Several months after the revolt of Cairo in 1798, inventor Nicolas-Jacques Conté and mathematician Gaspard Monge built a hot air balloon from paper, coloured with the tricolour red, white and blue of the French Republic. They launched the balloon above Azbakiyya Square above a crowd of spectators, but the balloon soon fell to earth, causing panic among the spectators.[67] The French had also planned to demonstrate hot air balloon flight during their celebrations of the anniversary of the founding of the French Republic in 1798, but the scientists had lost their equipment due to the Battle of the Nile.

Printing press

[edit]The printing press was first introduced to Egypt by Napoleon. He brought with his expedition a French, Arabic, and Greek printing press, which were far superior in speed, efficiency and quality to the nearest presses used in Istanbul. In the Middle East, Africa, India and even much of Eastern Europe and Russia, printing was a minor, specialised activity until the 18th century at least. From about 1720, the Mutaferrika Press in Istanbul produced substantial amounts of printing, some of which the Egyptian clerics were aware of at the time. Juan Cole reports that, Bonaparte was a master of what we would now call spin, and his genius for it is demonstrated by reports in Arabic sources that several of his more outlandish allegations were actually taken seriously in the Egyptian countryside.

[68]

Bonaparte's initial use of Arabic in his printed proclamations was rife with error. In addition to much of the awkwardly translated Arabic wording being unsound grammatically, often the proclamations were so poorly constructed that they were undecipherable.[69] The French Orientalist Jean Michel de Venture de Paradis, plausibly with the help of Maltese assistants, was responsible for translating the first of Napoleon's French proclamations into Arabic. The Maltese language is distantly related to the Egyptian dialect; and classical Arabic differs greatly in grammar, vocabulary, and idiom. Venture de Paradis, who had lived in Tunis, understood Arabic grammar and vocabulary, but did not know how to use them idiomatically.

The Sunni Muslim clerics of the Al-Azhar University in Cairo reacted incredulously to Napoleon's proclamations.[69]Abd al-Rahman al-Jabarti, a Cairene cleric and historian, received the proclamations with a combination of amusement, bewilderment, and outrage.[70][71] He berated the French's poor Arabic grammar and the infelicitous style of their proclamations. Over the course of Napoleon's invasion of Egypt, al-Jabarti wrote a wealth of material regarding the French and their occupation tactics. Among his observations, he rejected Napoleon's claim that the French were "muslims" (the wrong noun case was used in the Arabic proclamation, making it a lower case "m") and poorly understood the French concept of a republic and democracy – words which did not exist at the time in Arabic.[69]

Analysis

[edit]

In addition to its significance in the wider French Revolutionary Wars, the campaign had a powerful impact on the Ottoman Empire in general, and the Arab world in particular. The invasion demonstrated the military, technological, and organisational superiority of the Western European powers to the Middle East. This led to profound social changes in the region. The invasion introduced Western inventions, such as the printing press, and ideas, such as liberalism and incipient nationalism, to the Middle East, eventually leading to the establishment of Egyptian independence and modernization under Muhammad Ali Pasha in the first half of the 19th century and eventually the Nahda, or Arab Renaissance. To modernist historians, the French arrival marks the start of the modern Middle East.[72] Napoleon's destruction of the conventional Mamluk soldiers at the Battle of the Pyramids served as a reminder for modernising Arab monarchs to implement wide-ranging military reforms.[73]

While the Egyptian Islamic scholar and historian Al-Jabarti was critical of Napoleon and the French, he preferred them over the Ottomans. To Jabarti, Napoleon was compassionate towards Muslims and poor folk and he safeguarded the lives of innocents and civilians. This was at odds with the arrogance, cruelty and tyranny

of Ottoman rule, which he characterised as an un-Islamic system marked by corruption, backwardness and summary executions. Although they opposed the French Republic and the ideas of the French Revolution, both Jabarti and his disciple Hassan Al-Attar were astonished by French technological advancements and appreciated what they perceived as the fair nature of trials in the French judicial system.[74]

The campaign ultimately ended in failure, with 15,000 French troops killed in action and 15,000 by disease. Napoleon's reputation as a brilliant military commander remained intact and continued to increase, despite some of his failures during the campaign. This was due to his expert propaganda, such as his Courrier de l'Égypte, set up to propagandise the expeditionary force itself and support its morale. Such propaganda spread back to France, where news of defeats such as at sea in Aboukir Bay and on land in Syria were suppressed. Defeats could be blamed on the now-assassinated Kléber, leaving Napoleon free from blame and with a burnished reputation. This opened his way to power and he profited from his reputation by engineering his becoming First Consul in the coup d'état of 18 brumaire (November 1799).

Charges of imperialism

[edit]The French invasion of Egypt is widely regarded in contemporary academic circles to be the first act of modern European imperialism

and also criticised for its role in shaping the civilizing mission narrative of 19th century European colonial empires.[75]

According to Professor Edward W. Said, Napoleonic invasion led to the dominance of Orientalist narratives of the Muslim world:

"with Napoleon's occupation of Egypt, processes were set in motion between East and West that still dominate our contemporary cultural and political perspectives. And the Napoleonic expedition, with its great collective monument of erudition, the Description de l'Égypte, provided a scene or setting for Orientalism.. Napoleon's invasion of Egypt in 1798 and his foray into Syria have had by far the greater consequence for the modern history of Orientalism."[76]

Mamelukes in French service

[edit]Colonel Barthelemy Serra took the first steps towards creating a Mameluke Corps in France. On September 27, 1800, he wrote a letter from Cairo to the first consul, couched in an Oriental style. He regretted being very far away from Napoleon and offered his total devotion to the French nation and expressed the Mamelukes' wish to become the bodyguard to the first consul. They wished to serve him as living shields against those who would seek to harm him. The first consul became receptive of admitting a unit of carefully selected cavalrymen as his personal guard. He had an officer pay appropriate respects to the foreign troops and provided Napoleon himself with a full report to the number of refugees.[77]

French order of battle

[edit]Timeline and battles

[edit]

- 1798

- 19 May (30 Floréal year VI) – Departure from Toulon

- 11 June (23 Prairial year VI) – Capture of Malta

- 1 July (13 Messidor year VI) – Landing at Alexandria

- 13 July – Battle of Shubra Khit, French victory

- 21 July (3 Thermidor year VI) – Battle of the Pyramids, French land victory

- 1 and 2 August (14–15 Thermidor year VI) – Battle of the Nile, British naval victory over French squadron anchored in Aboukir Bay

- 10 August – Battle at Salheyeh, French victory

- 7 October – Battle of Sédiman, French victory

- 21 October (30 Vendémiaire) – Cairo Revolt

- 1799

- 11–19 February – Siege of El Arish, French victory

- 7 March – Siege of Jaffa, French victory

- 8 April – Battle at Nazareth, French victory, Junot with 500 defeats 3000 Ottoman soldiers

- 11 April – Battle of Cana, French victory, Napoleon wins a great battle against Ottomans

- 16 April (27 Germinal year VII) – Bonaparte relieves the troops under Kléber just as the latter are about to be overwhelmed at the foot of Mount Tabor

- 20 May (1 Prairial an VII) – Siege of Acre, French troops retire after eight assaults

- 1 August (14 Thermidor year VII) – Battle of Abukir, French victory

- 23 August (6 Fructidor year VII) – Bonaparte embarks on the frigate Muiron and abandons command to Kléber

- 1800

- 24 January (4 Pluviôse year VIII) – Kléber concludes the Convention of El Arish with the British admiral Sidney Smith

- February (Pluviôse-Ventôse year VIII) – French troops begin their withdrawal, but the British admiral Keith refuses to recognize the convention's terms

- 20 March (29 Ventôse year VIII) – Battle of Heliopolis, Kléber wins one last victory, against a force of 30,000 Ottomans

- 14 June (25 Prairial year VIII) – A Kurd named Suleiman al-Halabi assassinates Kléber in his garden in Cairo. General Menou, a convert to Islam, takes over command

- 3 September (16 Fructidor year VIII) – The British recapture Malta from the French

- 1801

- 8 March (17 Ventôse year IX) – British landing near Aboukir

- 21 March (30 Ventôse year IX) – Battle of Alexandria, French defeat, army under Menou digs in at Alexandria ready for the siege of Alexandria

- 31 March (10 Germinal year IX) – Ottoman army arrives at El-Arich

- 19 April (29 Germinal year IX) – British and Ottoman forces capture Fort Julien at Rosetta after a four-day bombardment, opening the Nile

- 27 June (8 Messidor year IX) – General Belliard surrenders in Cairo

- 31 August (13 Fructidor year IX) – Siege of Alexandria ends in Menou's surrender

See also

[edit]- Mediterranean campaign of 1798

- Anglo-Turkish War (1807–1809)

- Crusader invasions of Egypt – 1154–1169

References

[edit]- ^ Strathern 2008, p. 351.

- ^ Panzac 2005, p. 236.

- ^ a b Clodfelter 2017, p. 106.

- ^ Barthorp 1992, p. 6.

- ^ Chandler 1979, p. 78.

- ^ a b Mikaberidze 2020, pp. 131–133.

- ^ James 2003, p. 151.

- ^ Petry & Daly 1998, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Cole 2007, p. 13.

- ^ McLynn 1997, p. 167.

- ^ Maffeo 2000, p. 227.

- ^ Warner 1960, pp. 41, 224.

- ^ Watson 2003, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Fournier 1903, p. 120.

- ^ Chandler 1966, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Maffeo 2000, p. 256.

- ^ Maffeo 2000, p. 259.

- ^ Clowes 1899, pp. 353–355.

- ^ Cole 2007, pp. 8–10.

- ^ McLynn 1997, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2020, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Bonaparte 1808, pp. 58–59.

- ^ De Bellaigue 2017, p. 2.

- ^ Bainville 1997, p. 31.

- ^ Tulard 1999, p. 64.

- ^ Smith 1998, p. 140.

- ^ a b Thiers 1881, pp. 281–282.

- ^ Thiers 1881, pp. 290–291.

- ^ Hugo 1838, pp. 246–250.

- ^ Warner 1960, pp. 117–120.

- ^ Mullié 1851, p. 111.

- ^ De Bellaigue 2017, pp. 4–12.

- ^ De Bellaigue 2017, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Cherfils 1914, pp. 105, 125

- ^ Scurr 2021, p. 77.

- ^ Scurr 2021, p. 78.

- ^ Bernède 1998, p. 61.

- ^ Pigeard 2004.

- ^ Bernède 1998, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Chandler 1966, pp. 230–231.

- ^ Chandler 1966, pp. 235–236.

- ^ McLynn 1997, p. 189.

- ^ Chandler 1966, p. 236.

- ^ Clowes 1899, p. 402.

- ^ a b McLynn 1997, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Chandler 1966, pp. 238–240.

- ^ Rachlin 2013, p. 57.

- ^ Ludwig, Paul & Paul 1927, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Snodgrass 2017, p. 118.

- ^ Strathern 2008, p. 353.

- ^ Roberts 2015, p. 188.

- ^ McLynn 1997, pp. 197–198.

- ^ Société de militaires et de marins 1818a, p. 31.

- ^ a b Société de militaires et de marins 1818b, p. 443.

- ^ a b c d Société de militaires et de marins 1818b, p. 444.

- ^ Société de militaires et de marins 1818a, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Herold 1962, p. 255.

- ^ Herold 1962, p. 256.

- ^ Herold 1962, p. 259.

- ^ Herold 1962, p. 261.

- ^ Chandler 1966, pp. 242–243.

- ^ Fauvelet de Bourrienne 1836, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Rothenberg 1999, p. 54.

- ^ McLynn 1997, p. 198.

- ^ Fortescue 1906, pp. 854–855, 861–863.

- ^ McLynn 1997, pp. 180–183.

- ^ Scurr 2021, p. 80.

- ^ Cole 2007, p. 148.

- ^ a b c Cole 2007, p. 31.

- ^ 'Abd al-Rahman 1997, pp. 27–33, 33–41.

- ^ Cole 2007, p. 32.

- ^ Cleveland 2004, p. 65.

- ^ De Bellaigue 2017, p. 227.

- ^ Moreh 2004, pp. 183–184, 192, 195–198.

- ^ Bell 2015, p. 111.

- ^ W. Said 1979, pp. 42–43, 76.

- ^ Pawly 2012, p. 9.

References

[edit]- "Napoleon Was Here!". The National Library of Israel. Retrieved 22 November 2024.

- Bainville, Jacques (1997). Bonaparte en Égypte: poème (in French). Paris: Balland. ISBN 2-7158-1135-7.

- Barthorp, Michael (1992). Napoleon's Egyptian Campaigns 1798-1801. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9780850451269.

- Bernède, Allain (1998). Gérard-Jean Chaduc; Christophe Dickès; Laurent Leprévost (eds.). La campagne d'Égypte : 1798–1801 Mythes et réalités (in French). Paris: Musée de l'Armée. ISBN 978-2-901-41823-8.

- Burleigh, Nina (2007). Mirage. New York: Harper. ISBN 978-0-06-059767-2.

- Cherfils, Christian (1914). Bonaparte et l'Islam d'après les documents français & arabes. Pedone. OCLC 253080866.

- Cole, Juan (2007). Napoleon's Egypt: Invading the Middle East. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-6431-1.

- Cleveland, William L. (2004). A history of the modern Middle East. Michigan University Press. ISBN 0-8133-4048-9.

- Clodfelter, Michael (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015. Jefferson: McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. ISBN 9781476625850.

- Chandler, David (1966). The Campaigns of Napoleon. London: Macmillan. OCLC 4932949.

- De Bellaigue, Christopher (2017). The Islamic Enlightenment: The Struggle Between Faith and Reason – 1798 to Modern Times. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation. ISBN 978-0-87140-373-5.

- Clowes, William Laird (1899). The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900. Vol. IV. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company. OCLC 1040559851.

- Chandler, David (1979). Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars. London: Macmillan. OCLC 4932949.

- Fournier, August (1903). Napoleon the first: A biography. New York: Holt.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2020). The Napoleonic Wars A Global History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-995106-2.

- Forbes, Carl; Daly, Petry, M. W. (1998), Modern Egypt from 1517 to the End of the twentieth century, The Cambridge History of Egypt, vol. II, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-63313-3

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 'Abd al-Rahman, Al-Jabarti (1997). Ta'rikh, Muddat al-faransis bi misr. Princeton: Markus Wiener. ISBN 9781558760707.

- McLynn, Frank (1997). Napoleon:Biography. London: Cape. ISBN 0-224-04072-3.

- Fortescue, John William (1906). A History of the British Army. Vol. IV. London: Macmillan and Co. OCLC 1041559160.

- Moreh, Shmuel (2004). Napoleon in Egypt: Al-Jabarti's Chronicle of the French Occupation, 1798 – Expanded Edition. Princeton, New Jersey: Markus Wiener Publishers. ISBN 978-1-55876-337-1.

- Lovett, A. C.; Fletcher Macmunn, George (1911). The Armies of India. London: Black. OCLC 969696855.

- Scurr, Ruth (2021). Napoleon: A Life in Gardens and Shadows. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 9781784741006.

- Mullié, Charles (1851). Biographie des célébrités militaires des armées de terre et de mer de 1789 à 1850. Vol. 1. Paris: Poignavant. OCLC 1073690558.

- Rothenberg, Gunther E. (1999). The Napoleonic Wars. The Cassell history of warfare. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-35267-8.

- Bell, David (2015). "Epilogue: 1815–the Present". Napoleon: A Concise Biography. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-026271-6.

- Bonaparte, Napoleon (1808). Collection Générale et Complète de lettres... de Napoléon le Grand... Leipzig: Gräff. OCLC 1106670616.

- Herold, J. Christopher (1962). Bonaparte in Egypt. New York: Harper & Row.

- James, T. G. H (2003). Enlightening the British: Knowledge, Discovery and the Museum in the Eighteenth Century. British Museum Press. ISBN 0-7141-5010-X.

- Watson, William E. (2003). Tricolor and Crescent: France and the Islamic World. Greenwood. ISBN 0-275-97470-7.

- Mackesy, Piers (2013). British Victory in Egypt, 1801: The End of Napoleon's Conquest. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781134953578.

- Panzac, Daniel (2005). Barbary Corsairs. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004125940.

- Pawly, Ronald (2012). Napoleon's Mamelukes. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781780964195.

- W. Said, Edward (1979). "1: The Scope of Orientalism". Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-394-74067-X.

- Rachlin, Harvey (2013). "The Rosetta Stone". Lucy's Bones, Sacred Stones, & Einstein's Brain: The Remarkable Stories Behind the Great Objects and Artifacts of History, From Antiquity to the Modern Era. Garrett County Press. ISBN 978-1939430915.

- Ludwig, Emil; Paul, Eden; Paul, Cedar (1927). Napoleon. London: George Allen & Unwin. OCLC 949387935.

- Pigeard, Alain (2004). Dictionnaire des batailles de Napoléon : 1796–1815 (in French). Paris: Tallandier. ISBN 2-84734-073-4.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Greenhill Napoleonic Wars Data Book : Actions and Losses in Personnel, Colours, Standards and Artillery, 1792–1815. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.

- Société de militaires et de marins (1818a). Dictionnaire historique des batailles, siéges, et combats de terre et de mer, qui ont eu lieu pendant la Révolution Française (in French). Menard et Desenne.

- Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2017). "The Chronology: Summer 1798–1800". World Epidemics: A Cultural Chronology of Disease from Prehistory to the Era of Zika. McFarland. ISBN 978-1476671246.

- Société de militaires et de marins (1818b). Dictionnaire historique des batailles, siéges, et combats de terre et de mer: qui ont en lieu pendant la révolution Française, Volume 3 (in French). Menard et Desenne.

- Strathern, Paul (2008). "The Retreat from Acre". Napoleon in Egypt. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0553905885.

- Fauvelet de Bourrienne, Louis Antoine (1836). Memoirs of Napoleon Bonaparte. London: Bentley. OCLC 1068769035.

- Roberts, Andrew (2015). Napoleon: A Life. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0698176287.

- Tulard, Jean (1999). Dictionnaire Napoléon (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 2-213-60485-1.

External links

[edit] Media related to Expédition d’Égypte at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Expédition d’Égypte at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by French invasion of Switzerland |

French Revolution: Revolutionary campaigns French invasion of Egypt and Syria |

Succeeded by Irish Rebellion of 1798 |

- French invasion of Egypt and Syria

- Conflicts in 1798

- Conflicts in 1799

- Conflicts in 1800

- Conflicts in 1801

- Invasions by France

- Military history of Egypt

- Napoleonic Wars

- Wars involving Ottoman Egypt

- Wars involving the United Kingdom

- 18th century in France

- 19th century in France

- 18th century in Egypt

- 19th century in Egypt

- 1798 in Egypt

- 1799 in Egypt

- 1800 in Egypt

- 1801 in Egypt

- 1799 in Ottoman Syria

- French colonisation in Africa

- 18th century in the British Empire

- 19th century in the British Empire

- Invasions of Ottoman Egypt

- Invasions of Ottoman Syria

- Egypt–France relations