Fred Thompson

Fred Thompson | |

|---|---|

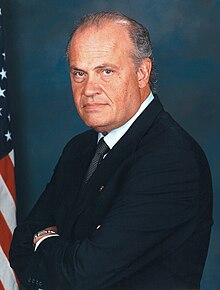

Official portrait of Thompson | |

| United States Senator from Tennessee | |

| In office December 2, 1994 – January 3, 2003 | |

| Preceded by | Harlan Mathews |

| Succeeded by | Lamar Alexander |

| Chair of the Senate Governmental Affairs Committee | |

| In office January 20, 2001 – June 6, 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Joe Lieberman |

| Succeeded by | Joe Lieberman |

| In office January 3, 1997 – January 3, 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Ted Stevens |

| Succeeded by | Joe Lieberman |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Freddie Dalton Thompson August 19, 1942 Sheffield, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died | November 1, 2015 (aged 73) Nashville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 5 |

| Education | University of Memphis (BA) Vanderbilt University (JD) |

| Signature |  |

Freddie Dalton Thompson[4] (August 19, 1942 – November 1, 2015) was an American politician, attorney, lobbyist, columnist, actor, and radio personality. A member of the Republican Party, he served as a United States senator from Tennessee from 1994 to 2003. He was an unsuccessful candidate in the Republican Party presidential primaries for the 2008 United States presidential election.

He chaired the International Security Advisory Board at the U.S. Department of State, was a member of the U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission, a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, as well as a visiting fellow with the American Enterprise Institute, specializing in national security and intelligence.[5]

Usually credited as Fred Dalton Thompson, he appeared in a number of movies and television shows including Matlock, The Hunt for Red October, Die Hard 2, In the Line of Fire, Days of Thunder, and Cape Fear, as well as in commercials. He frequently portrayed governmental authority figures and military men.[6] In the final months of his U.S. Senate term in 2002, Thompson joined the cast of the NBC television series Law & Order, starring as Manhattan District Attorney Arthur Branch.[7]

Early life

[edit]Thompson was born at Helen Keller Memorial Hospital in Sheffield, Alabama on August 19, 1942,[8] the son of Ruth Inez (née Bradley) and Fletcher Session Thompson (born Lauderdale County, Alabama, August 26, 1919, and died in Lawrenceburg, Tennessee, May 27, 1990), who was an automobile salesman. Fred Thompson had English and distant Dutch ancestry.[9][10] He attended public school in Lawrenceburg, graduating from Lawrence County High School in 1960[11] where he played high-school football.[12] Thereafter, he worked days in the local post office, and nights at the Murray bicycle assembly plant.[13]

Thompson grew up going to churches in the Churches of Christ.[14] He said that his values came from "sitting around the kitchen table" with his parents, and from the Church of Christ. While talking to reporters at an event in South Carolina, Thompson said, "I attend church when I'm in Tennessee. I'm [living] in McLean right now. I don't attend regularly when I'm up there."[15] Later in his adulthood, Thompson occasionally attended Vienna Presbyterian Church in Vienna, Virginia.[16] He did not speak much about religion during his 2008 presidential campaign. He said, "Me getting up and talking about what a wonderful person I am and that sort of thing, I'm not comfortable with that, and I don't think it does me any good."[15]

In September 1959, at the age of 17, Thompson married Sarah Elizabeth Lindsey.[17] Their son, Freddie Dalton "Tony" Thompson Jr.,[2] was born in April 1960.[18] Their son Daniel and daughter Elizabeth were born not long afterwards.[19]

Thompson attended Florence State College (now the University of North Alabama), becoming the first member of his family to attend college.[20] He later transferred to Memphis State University (now the University of Memphis), where he earned a double degree in philosophy and political science in 1964.[13] He then received a scholarship to study law at the Vanderbilt University Law School, graduating with a Juris Doctor degree in 1967.[20] While Thompson was attending law school, he and Sarah both worked to pay for his education and support their three children.[19] Thompson and his first wife divorced in 1985.[21]

Career as an attorney

[edit]Thompson was admitted to the state bar of Tennessee in 1967. At that time, he shortened his first name from Freddie to Fred.[22] He worked as an assistant U.S. attorney from 1969 to 1972,[23] successfully prosecuting bank robberies and other cases.[13] Thompson was the campaign manager for Republican U.S. Senator Howard Baker's re-election campaign in 1972, and was minority counsel to the Senate Watergate Committee in its investigation of the Watergate scandal (1973–1974).

In the 1980s, Thompson worked as an attorney, with law offices in Nashville and Washington, DC,[24] handling personal injury claims and defending people accused of white collar crimes.[25] He also accepted appointments as special counsel to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (1980–1981), special counsel to the Senate Intelligence Committee (1982), and member of the Appellate Court Nominating Commission for the State of Tennessee (1985–1987).[13][20]

His clients included a German mining group and Japan's Toyota Motors Corporation.[19] Thompson served on various corporate boards. He also did legal work and served on the board of directors for engineering firm Stone & Webster.[26]

Role in Watergate hearings

[edit]

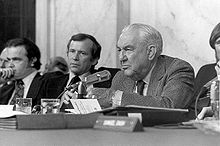

In 1973, Thompson was appointed minority counsel to assist the Republican senators on the Senate Watergate Committee, a special committee convened by the U.S. Senate to investigate the Watergate scandal.[27] Thompson was sometimes credited for supplying Republican Senator Howard Baker's famous question, "What did the President know, and when did he know it?"[28] This question is said to have helped frame the hearings in a way that eventually led to the downfall of President Richard Nixon.[29] The question remains popular and is often invoked by pundits commenting on political scandals.[30]

A Republican staff member, Donald Sanders, found out about the White House tapes and informed the committee on July 13, 1973. Thompson was informed of the existence of the tapes, and he, in turn, informed Nixon's attorney, J. Fred Buzhardt.[31] "Even though I had no authority to act for the committee, I decided to call Fred Buzhardt at home," Thompson later wrote,[32] "I wanted to be sure that the White House was fully aware of what was to be disclosed so that it could take appropriate action."

Three days after Sanders's discovery, at a public, televised committee hearing, Thompson asked former White House aide Alexander Butterfield the famous question, "Mr. Butterfield, were you aware of the installation of any listening devices in the Oval Office of the President?" thereby publicly revealing the existence of tape recordings of conversations within the White House.[19][27] National Public Radio later called that session and the discovery of the Watergate tapes "a turning point in the investigation."[33]

Thompson's appointment as minority counsel to the Senate Watergate committee reportedly upset Nixon, who believed Thompson was not skilled enough to interrogate unfriendly witnesses and would be outfoxed by the committee Democrats. According to historian Stanley Kutler, however, Thompson and Baker "carried water for the White House, but I have to give them credit—they were watching out for their interests, too ... They weren't going to mindlessly go down the tubes [for Nixon]."[28]

Journalist Scott Armstrong, a Democratic investigator for the Senate Watergate Committee, is critical of Thompson for having disclosed the committee's knowledge of the tapes to Buzhardt during an ongoing investigation, and says Thompson was "a mole for the White House" and that Thompson's actions gave the White House a chance to destroy the tapes. Thompson's 1975 book At That Point in Time, in turn, accused Armstrong of having been too close to The Washington Post's Bob Woodward and of leaking committee information to him. In response to renewed interest in this matter, in 2007 during his presidential campaign, Thompson said, "I'm glad all of this has finally caused someone to read my Watergate book, even though it's taken them over 30 years."[34]

Corruption case against Tennessee governor

[edit]In 1977, Thompson represented Marie Ragghianti, a former Tennessee Parole Board chair, who had been fired for refusing to release felons after they had bribed aides to Democratic Governor Ray Blanton to obtain clemency.[35] With Thompson's assistance, Ragghianti filed a wrongful termination suit against Blanton's office. During the trial, Thompson helped expose the cash-for-clemency scheme that eventually led to Blanton's removal from office.[19] In July 1978, a jury awarded Ragghianti $38,000 ($139,165.09 in 2016 dollars)[36] in back pay and ordered her reinstatement.[35]

Career as a lobbyist

[edit]

Thompson earned about $1 million in total from his lobbying efforts. Except for the year 1981, his lobbying never amounted to more than one-third of his income.[37] According to the Memphis Commercial Appeal:

Fred Thompson earned about half a million dollars from Washington lobbying from 1975 through 1993 ... Lobbyist disclosure records show Thompson had six lobbying clients: Westinghouse, two cable television companies, the Tennessee Savings and Loan League, the Teamsters Union's Central States Pension Fund, and a Baltimore-based business coalition that lobbied for federal grants.[37]

Thompson lobbied Congress on behalf of the Tennessee Savings and Loan League to pass the Garn–St. Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982, which deregulated the savings and loan industry.[19] A large congressional majority and President Ronald Reagan supported the act, but it was said to be a factor that led to the savings and loan crisis.[38] Thompson received $1,600 for communicating with some congressional staffers on this issue.[37]

When Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide was overthrown in 1991, Thompson made a telephone call to White House Chief of Staff John H. Sununu advocating restoration of Aristide's government, but said that was as a private citizen, not on a paid basis on Aristide's behalf.[39]

Billing records show that Thompson was paid for about 20 hours of work in 1991 and 1992 on behalf of the National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Association, a family planning group trying to ease a George H. W. Bush administration regulation on abortion counseling in federally funded clinics.[40][41]

After Thompson was elected to the Senate, two of his sons followed him into the lobbying business, but generally avoided clients where a possible conflict of interest might appear.[42] When he left the Senate, some of his political action committee's fees went to the lobbying firm of one of his sons.[43]

Initial acting career

[edit]Marie Ragghianti's case became the subject of a book, Marie which was written by Peter Maas and published in 1983. The film rights were purchased by director Roger Donaldson, who, after traveling to Nashville to speak with the people involved with the original case, asked Thompson if he wanted to play himself. The resulting film, Marie, was Thompson's first acting role and was released in 1985. Roger Donaldson then cast Thompson in the part of CIA director Marshall in the 1987 film No Way Out.[44] He played the head of FBI special-agent training in the 1988 comedy Feds; in the trailer, the FBI disclaimed any connection with the film. In 1990, he was cast as Ed Trudeau, the head of Dulles Airport, in the action sequel Die Hard 2, as Rear Admiral Painter in The Hunt for Red October, and as Big John, the President of NASCAR, in the movie Days of Thunder (patterned on 'Big' Bill France).

Thompson went on to be cast in many films including as Tom Broadbent in Cape Fear (1991) and White House Chief of Staff Harry Sargent in In the Line of Fire (1993). A 1994 New York Times profile wrote, "When Hollywood directors need someone who can personify governmental power, they often turn to him."[6] He also appeared in several television shows including Roseanne, Matlock and (eventually) a role on Law & Order.

United States Senate tenure

[edit]Election campaigns

[edit]

In 1994, Thompson was elected to finish the remaining two years of Al Gore's unexpired U.S. Senate term. During the 1994 campaign, Thompson's opponent was longtime Nashville Congressman Jim Cooper. Thompson campaigned in a red pickup truck, and Cooper charged Thompson "is a lobbyist and actor who talks about lower taxes, talks about change, while he drives a rented stage prop."[45] In a good year for Republican candidates,[46] Thompson defeated Cooper in a landslide, overcoming Cooper's early 20% lead in the polls to defeat him by an even greater margin.[47] On the same night Thompson was elected to fill Gore's unexpired term, political newcomer Bill Frist, a Nashville heart surgeon, defeated three-term incumbent Democrat Jim Sasser, the chairman of the Senate Budget Committee, for Tennessee's other Senate seat, which was up for a full six-year term. The twin victories by Thompson and Frist gave Republicans control of both of Tennessee's Senate seats for the first time since Sasser ousted incumbent Bill Brock in 1976.

In 1996, Thompson was reelected (for the term ending January 3, 2003) with 61% of the vote, defeating Democratic attorney Houston Gordon of Covington, Tennessee, even as Bill Clinton and running mate Al Gore narrowly carried the state by less than three percentage points on their way to re-election.[48] During this campaign, Mike Long served as Thompson's chief speechwriter.[49]

Committee assignments

[edit]

In 1996, Thompson was a member of the Committee on Governmental Affairs when the committee investigated the alleged Chinese attempts to influence American politics. Thompson says he was "largely stymied" during these investigations by witnesses declining to testify, claiming the right not to incriminate themselves or by simply leaving the country.[50] Thompson explained, "Our work was affected tremendously by the fact that Congress is a much more partisan institution than it used to be."[51]

Thompson became committee chairman in 1997, but was reduced to ranking minority member when the Democrats took control of the Senate in 2001.[52] Thompson served on the Finance Committee (dealing with health care, trade, Social Security, and taxation), the Intelligence Committee, and the National Security Working Group.[53]

Thompson's work included investigation of the "Umm Hajul controversy" which involved the death of Tennessean Lance Fielder during the Gulf War. During his term, he supported campaign finance reform, opposed proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and promoted government efficiency and accountability.[13] During the 1996 presidential debates, he also served as a Clinton stand-in to help prepare Bob Dole.[13]

On February 12, 1999, the Senate voted on the Clinton impeachment. The perjury charge was defeated with 45 votes for conviction, and 55, including Thompson, against. The obstruction of justice charge was defeated with 50, including Thompson, for conviction, and 50 against. Conviction on impeachment charges requires the affirmative votes of 67 senators.

Campaign co-chairman for John McCain's 2000 presidential campaign

[edit]In the 2000 Republican Party presidential primaries, Thompson backed former Tennessee Governor Lamar Alexander, who eventually succeeded Thompson in the Senate two years later. When Alexander dropped out, Thompson endorsed Senator John McCain's bid and became his national co-chairman.[54] After George W. Bush won the primaries, both McCain and Thompson were considered as potential running mates.[55][56]

Ratings

[edit]

Thompson's rating from the American Conservative Union was 86.1 (1995 to 2002), compared to 89.3 for Bill Frist, and 82.3 for John McCain.[57][58] Senator Susan Collins (R-Maine) characterized her colleague this way: "I believe that Fred is a fearless senator. By that I mean he was never afraid to cast a vote or take a stand, regardless of the political consequences."[59] Thompson was "on the short end of a couple of 99–1 votes", voting against those who wanted to federalize matters that he believed were properly left to state and local officials.[60]

With Thompson's decision to campaign for the 2008 Republican presidential nomination, his Senate record received some criticism from people who say he was "lazy" compared to other senators.[61] Critics say that few of his proposals became law, and point to a 1998 quote: "I don't like spending 14- and 16-hour days voting on 'sense of the Senate' resolutions on irrelevant matters. There are some important things we really need to get on with—and on a daily basis, it's very frustrating." Defenders say he spent more time in preparation than other senators. Paul Noe, a former staffer, told The New York Times, "On the lazy charge, I have to chuckle because I was there sometimes until 1 in the morning working with the man."[62]

Personal life during Senate tenure

[edit]

In the years after his divorce, Thompson was romantically linked to country singer Lorrie Morgan, Republican fundraiser Georgette Mosbacher, future Counselor to the President Kellyanne Conway, and columnist Margaret Carlson.[63]

In July 1996, Thompson began dating Jeri Kehn (born 1966) and the two married almost six years later on June 29, 2002.[64] When he was asked in an Associated Press survey of the candidates in December 2007, to name his favorite possession he replied, tongue-in-cheek, "trophy wife".[65] The couple had two children together, a daughter Hayden born in 2003, and a son Samuel born in 2006.[66][67][68][69]

On January 30, 2002, Thompson's daughter Elizabeth "Betsy" Thompson Panici died from a brain injury resulting from cardiac arrest after what was determined to be an accidental overdose of prescription drugs.[70]

Initial post-Senate life and career

[edit]Thompson was not a candidate for reelection in 2002. He had previously stated that he was unwilling to make serving in the Senate a long-term career. While he announced in the wake of the September 11, 2001 attacks his intention to seek reelection (declaring, "now is not the time for me to leave"), upon further reflection, he decided against running for reelection.[44] The decision seems to have been prompted in large part by the death of his daughter.[50][71]

The only lobbying work Thompson did after leaving the Senate in 2003 was for the London-based reinsurance company Equitas Ltd. He was paid $760,000 between 2004 and 2006 to help prevent passage of legislation that Equitas said unfairly singled them out for unfavorable treatment regarding asbestos claims.[26] Thompson's spokesman Mark Corrallo said that Thompson was proud to have been a lobbyist and believed in Equitas' cause.[72]

Return to acting

[edit]As Thompson prepared to depart the Senate, he resumed his acting career. In 2002, during the final months of his Senate term, Thompson joined the cast of the NBC television series Law & Order, playing conservative District Attorney Arthur Branch, a role that he would ultimately portray for the next five years. Thompson began filming during the August 2002 Senate recess.[13] He made occasional appearances in the same role on other TV shows, such as Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, Law & Order: Criminal Intent, and the pilot episode of Conviction.

During these years, Thompson also had roles in films including Racing Stripes (2005) and Looking for Comedy in the Muslim World (2005). He portrayed a fictional president of the United States in Last Best Chance (2005), as well as two historical presidents in TV movies: Ulysses S. Grant in Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (2007) and the voice of Andrew Jackson in Rachel and Andrew Jackson: A Love Story (2001).[73]

Thompson, in 2007, again paused his acting career in order to pursue political options, this time stepping back from acting in order to accommodate a potential campaign for the presidency. On May 30, 2007, he asked to be released from the Law & Order role, potentially in preparation for a presidential bid.[7] Due to concerns about the equal-time rule, reruns featuring the Branch character were not shown on NBC while Thompson was a potential or actual presidential candidate, but TNT episodes were unaffected.[74]

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma diagnosis

[edit]Thompson was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL), a form of cancer, in 2004. In 2007, Thompson stated, "I have had no illness from it, or even any symptoms. My life expectancy should not be affected. I am in remission, and it is very treatable with drugs if treatment is needed in the future—and with no debilitating side effects." Reportedly indolent, Thompson's NHL was the lowest of three grades of NHL,[75] and was the rare nodal marginal zone lymphoma. It accounts for only 1–3% of all cases.[76]

Political activities

[edit]

From 2002 to 2005, Thompson was head of the Federal City Council, a group of business, civic, education, and other leaders interested in economic development in Washington, DC.[77]

In March 2003, Thompson was featured in a commercial by the conservative nonprofit group Citizens United which advocated for the invasion of Iraq, "When people ask what has Saddam done to us, I ask, what had the 9/11 hijackers done to us--before 9/11."[78]

Thompson did voice-over work at the 2004 Republican National Convention.[79] While narrating a video for that convention, Thompson observed: "History throws you what it throws you, and you never know what's coming."[80]

After the retirement of Supreme Court Associate Justice Sandra Day O'Connor in 2005, President George W. Bush appointed Thompson to an informal position to help guide the nomination of John Roberts through the United States Senate confirmation process.[81] Roberts' nomination as associate justice was cancelled following the death of Chief Justice William Rehnquist; he was renominated and confirmed as Chief Justice instead.

Until July 2007, Thompson was Chair of the International Security Advisory Board, a bipartisan advisory panel that reports to the Secretary of State and focuses on emerging strategic threats.[82] In that capacity, he advised the State Department about all aspects of arms control, disarmament, international security, and related aspects of public diplomacy.[83]

Legal defense for Lewis Libby

[edit]In 2006, he served on the advisory board of the legal defense fund for I. Lewis "Scooter" Libby Jr., who was indicted and later convicted of lying to federal investigators during their investigation of the Plame affair.[84][85] Thompson, who had never met Libby before volunteering for the advisory board, said he was convinced that Libby was innocent.[44] The Scooter Libby Legal Defense Fund Trust set out to raise more than $5 million to help finance the legal defense of Vice President Dick Cheney's former chief of staff.[86] Thompson hosted a fundraiser for the Libby defense fund at his home in McLean, Virginia.[87] After Bush commuted Libby's sentence,[88] Thompson released a statement: "I am very happy for Scooter Libby. I know that this is a great relief to him, his wife and children. This will allow a good American, who has done a lot for his country, to resume his life."[89]

Work as a radio analyst

[edit]In 2006, he signed on with ABC News Radio to serve as senior analyst and vacation replacement for Paul Harvey.[90] He used that platform to spell out his positions on a number of political issues. A July 3, 2007, update to Thompson's ABC News Radio home page referred to him as a "former ABC News Radio contributor", indicating that Thompson had been released from his contract with the broadcaster.[91] He did not return after his campaign ended.

Work as a columnist

[edit]Thompson signed a deal with Salem Communications's Townhall.com to write for the organization's magazine, Townhall, from April 23, 2007, until August 21, 2007,[92] and again from June 8, 2008, until November 17, 2008.[93]

2008 presidential campaign

[edit]

Thompson ran for the Republican nomination in the 2008 United States presidential election cycle. He won 11 delegates in the Republican primaries before dropping out of the race in January 2008.

On March 11, 2007, Thompson appeared on Fox News Sunday to discuss the possibility of a 2008 candidacy for the presidency. Two weeks later Thompson asked to be released from his television contract, potentially in preparation for a presidential bid.[7] Thompson formed a presidential exploratory committee regarding his possible 2008 campaign for president on June 1, 2007,[94] but unlike most candidate exploratory groups, Thompson's organized as a 527 group.[95]

Thompson continued to be mentioned as a potential candidate, but did not officially declare his candidacy. On June 12, he told Jay Leno on The Tonight Show that while he did not crave the presidency itself, he would like to do things that he could only do by holding that office.[96] A New York Times article cited Thompson's aides as saying on July 18 that he planned to enter the race just after Labor Day, followed by a national announcement tour.[97]

On September 5, 2007, Thompson made his candidacy official, announcing on The Tonight Show that "I'm running for president of the United States" and running an ad during a Republican presidential candidates' debate on Fox News.[98] In both instances he pointed people to his campaign website to watch a 15-minute video detailing his platform. His campaign entrance was described as "lackluster"[99] and "awkward"[100] despite high expectations in anticipation of his joining the race.[101] Thompson was endorsed by the Virginia Society for Human Life and several other anti-abortion organizations.[102][103]

In nationwide polling toward the end of 2007, Thompson's support in the Republican primary election was sliding, with Thompson placing either third or fourth in polls.[104][105] On January 22, 2008, after attracting little support in the early primaries, he confirmed that he had withdrawn from the presidential race.[106] In a statement issued by his campaign he said:

Today I have withdrawn my candidacy for President of the United States. I hope that my country and my party have benefited from our having made this effort. Jeri and I will always be grateful for the encouragement and friendship of so many wonderful people.

Post-presidential campaign

[edit]Political activities

[edit]Thompson spoke at the 2008 Republican National Convention on September 2 in Minnesota, where he described in graphic detail presumptive Republican nominee John McCain's torture at the hands of the North Vietnamese during his imprisonment and gave an endorsement of McCain for president.[107]

Thompson campaigned in support of the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact.[108]

Acting career

[edit]Thompson signed an agreement to be represented as an actor by the William Morris Agency.[109] In 2009, he returned to acting with a guest appearance on the ABC television series Life on Mars,[110] and as William Jennings Bryan in the TV movie Alleged (2010), based on the Scopes Monkey Trial.[111] Thompson portrayed Frank Michael Thomas in the CBS series The Good Wife, based on himself. He also had roles in Disney's Secretariat (2010) and the horror film Sinister (2012). In 2014, he appeared in the film Persecuted, focusing on religious freedom, government surveillance, and censorship.[112]

Radio career

[edit]On March 2, 2009, he took over Westwood One's East Coast noon time slot, hosting the talk radio program The Fred Thompson Show, after Bill O'Reilly ended The Radio Factor.[113] It was co-hosted for a time by his wife, Jeri. Thompson's final show for Westwood One was aired on January 21, 2011. Douglas Urbanski took Thompson's place in the Westwood One syndication lineup.[114]

Work as an advertising spokesman

[edit]In May 2010, Thompson became an advertising spokesman for American Advisors Group, a reverse mortgage lender.[115][116]

Memoir

[edit]Thompson's memoir, Teaching the Pig to Dance: A Memoir of Growing up and Second Chances, was published in 2010.[117][118]

Death and funeral

[edit]On the morning of November 1, 2015, Thompson died at the age of 73; the cause of death was a recurrence of lymphoma.[119] His funeral was held on November 6, 2015, in Nashville with U.S. Senators John McCain and Lamar Alexander in attendance.[120] He was interred at Mimosa Cemetery in Lawrenceburg, Tennessee later that day.[121]

The Fred D. Thompson U.S. Courthouse and Federal Building was named in his honor pursuant to legislation signed into law in June 2017.[122]

Political positions

[edit]

Thompson said that federalism was his "lodestar", which provides "a basis for a proper analysis of most issues: 'Is this something government should be doing? If so, at what level of government?'"[60]

Thompson said that "Roe v. Wade was bad law and bad medical science"; he felt that judges should not be determining social policy.[123] However, he also said that the government should not criminally prosecute women who undergo early-term abortions.[124][125] He did not support a federal ban on gay marriage, but would have supported a constitutional amendment to keep a state's recognition of such marriages from resulting in all states having to recognize them.[126]

He said that citizens are entitled to keep and bear arms if they do not have criminal records.[127] The Gun Owners of America says that he voted pro-gun in 20 of 33 gun-related votes during his time in the Senate.[128]

Thompson said that U.S. borders should be secured before considering comprehensive immigration reform,[129] but he also supported a path to citizenship for illegal aliens saying, "You're going to have to, in some way, work out a deal where they can have some aspirations of citizenship, but not make it so easy that it's unfair to the people waiting in line and abiding by the law."[130] Thompson supported the U.S. 2003 invasion of Iraq[131] and was opposed to withdrawing troops,[132] but believed that "mistakes have been made" since the invasion.[133]

Thompson initially supported the McCain–Feingold campaign finance legislation, but he later said that certain parts should be repealed.[134] He was skeptical that human efforts cause global warming and pointed to parallel warming on Mars and other planets as an example.[135]

Filmography

[edit]Thompson's acting roles were credited as Fred Dalton Thompson, unless otherwise noted.

Film

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1985 | Marie | Himself | debut, credited as Fred Thompson |

| 1987 | No Way Out | CIA Director Marshall | |

| 1988 | Feds | Bill Bilecki | |

| 1989 | Fat Man and Little Boy | Major General Melrose Hayden Barry | |

| 1990 | The Hunt for Red October | Rear Admiral Joshua Painter | |

| Days of Thunder | Big John | ||

| Die Hard 2 | Ed Trudeau | ||

| 1991 | Flight of the Intruder | JAGC Captain at Court-Martial | Uncredited |

| Class Action | Dr. Getchell | ||

| Necessary Roughness | Carver Purcell | ||

| Cape Fear | Tom Broadbent | ||

| Curly Sue | Bernie Oxbar | ||

| 1992 | Aces: Iron Eagle III | Stockman | |

| Thunderheart | William Dawes | ||

| White Sands | Arms dealer | Uncredited | |

| 1993 | Born Yesterday | Sen. Hedges | |

| In the Line of Fire | White House Chief of Staff Harry Sargent | ||

| 1994 | Baby's Day Out | FBI Agent Dale Grissom | |

| 2002 | Download This | Himself | |

| 2005 | Racing Stripes | Sir Trenton | Voice |

| Looking for Comedy in the Muslim World | Himself | ||

| 2010 | The Genesis Code | Judge Hardin | |

| Secretariat | Arthur "Bull" Hancock | ||

| Ironmen | Governor Neeley | ||

| Alleged | William Jennings Bryan | credited as Sen. Fred Dalton Thompson | |

| 2012 | The Last Ride | O'Keefe | |

| Sinister | Sheriff | ||

| 2013 | Unlimited | Harold Finch | |

| 2014 | Persecuted | Fr. Charles Luther | |

| 23 Blast | Coach Powers | ||

| 2015 | A Larger Life | Robert Parker | |

| 90 Minutes in Heaven | Jay B. Perkins | ||

| 2016 | God's Not Dead 2 | Senior Pastor | posthumous release, credited as Fred Thompson |

Television

[edit]| Year | Series | Role | Episode count |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1988 | Wiseguy | Knox Pooley | 3 episodes |

| Unholy Matrimony | Frank Sweeny | TV movie | |

| 1989 | China Beach | Lt. Col. Reinhardt | 1 episode |

| Roseanne | Keith Faber | 1 episode | |

| Matlock | Gordon Lewis | 2 episodes | |

| In the Heat of the Night | Tommy | Season 2 - Episode 18 | |

| 1992 | Bed of Lies | Richard 'Racehorse' Haynes | TV movie |

| Stay the Night | Det. Malone | TV movie | |

| Day-O | Frank DeGeorgio | TV movie | |

| Keep the Change | Otis | TV movie | |

| 1993 | Matlock | Prosecutor McGonigal | 1 episode |

| Barbarians at the Gate | James D. Robinson III | TV movie | |

| 2000 | Sex and the City | Politician on TV | 1 episode |

| 2001 | Rachel and Andrew Jackson: A Love Story | President Andrew Jackson | Voice, TV movie |

| 2002–2007 | Law & Order | D.A. Arthur Branch | 116 episodes |

| 2003–2006 | Law & Order: Special Victims Unit | D.A. Arthur Branch | 11 episodes |

| 2004 | Evel Knievel | Jay Sarno | TV movie |

| 2005–2006 | Law & Order: Trial by Jury | D.A. Arthur Branch | 13 episodes |

| 2005 | Law & Order: Criminal Intent | D.A. Arthur Branch | 1 episode |

| 2006 | Conviction | D.A. Arthur Branch | 1 episode |

| 2007 | Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee | President Ulysses S. Grant | TV movie, credited as Fred Thompson |

| 2009 | Life on Mars | NYPD Chief Harry Woolf | 1 episode |

| 2011–2012 | The Good Wife | Frank Michael Thomas | 2 episodes |

| 2015 | Allegiance | FBI Director | 4 episodes |

Book authored

[edit]- At That Point in Time: The Inside Story of the Senate Watergate Committee. New York: Quadrangle. 1975. ISBN 978-0812905366.

- Teaching the Pig to Dance: A Memoir of Growing Up and Second Chances. New York: Crown Forum. 2010. ISBN 978-0307460288.

Electoral history

[edit]| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Fred Thompson (Incumbent) | 1,091,554 | 61.37% | +0.93% | |

| Democratic | Houston Gordon | 654,937 | 36.82% | ||

| Independent | John Jay Hooker | 14,401 | 0.81% | ||

| Majority | 436,617 | 24.55% | +2.72% | ||

| Republican hold | Swing | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Fred Thompson | 885,998 | 60.44% | ||

| Democratic | Jim Cooper | 565,930 | 38.61% | ||

| Majority | 320,068 | 21.83% | −16.07% | ||

| Republican gain from Democratic | Swing | ||||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Fred Thompson, actor and presidential candidate, dies at age 73". Grasswire.com. November 1, 2015. Archived from the original on January 7, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ^ a b Humphrey, Tom (September 7, 2007). "Fred, Freddie — he's still F.D. Thompson: New details emerge on personal life of newly announced candidate". Knoxville News Sentinel. Archived from the original on April 30, 2013. Retrieved September 8, 2007.

- ^ Mathews, Joe. "An in-law-made man", Los Angeles Times (September 6, 2007): "Thompson stopped using the name Freddie in his professional dealings and became Fred."

- ^ [1][2][3]

- ^

- American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Scholars & Fellows Archived December 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- Thompson, Fred. "Modern Political Archives: Fred Thompson Papers, 1993–2002". University of Tennessee. Archived from the original on September 8, 2006. Retrieved April 8, 2007.

- "U.S. Department of State". Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Bragg, Rick (November 12, 1994). "Grits and Glitter Campaign Helps Actor Who Played a Senator Become One". The New York Times. pp. Sec. 1, p. 10. Archived from the original on December 16, 2012. Retrieved April 8, 2007.

- ^ a b c Associated Press and Cameron, Carl. "Fred Thompson Quits 'Law & Order,' Moves Closer to 2008 White House Bid", Fox News (May 31, 2007).

- ^ Thompson, Fred (May 18, 2010). Teaching the Pig to Dance: A Memoir of Growing Up and Second Chances. Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-46030-1.

- ^ Fred Dalton Thompson Biography (1942-) via filmreference.com.

- ^ Reitwiesner, William Addams. "Ancestry of Fred Thompson". self-published, non-authoritative. Retrieved April 8, 2007.

- ^ TV or Oval Office? U of M Grad Thompson Faces Decision

- ^ "Fred Thompson: A big and joyous life (Opinion) - CNN.com". CNN. November 6, 2015. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lawrimore, Erin. "Biography/History" Archived October 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, University of Tennessee Special Collections Library (2005).

- ^ "Future president? Fred Thompson's church roots draw interest". The Christian Chronicle. April 1, 2007. Retrieved September 9, 2021.

- ^ a b Kim Chipman, "Thompson Says He's No Churchgoer, Won't Tout Religion on Stump", Bloomberg (September 11, 2007).

- ^ Brian Kaylor. "Reports Conflict About Fred Thompson's Church Membership, Attendance". Archived from the original on April 13, 2016. Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- ^ Mathews, Joe (September 6, 2007). "Thompson wed his ambition". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 8, 2007. Retrieved September 7, 2007.: "In the summer of 1959 ... Lindsey told Thompson she was pregnant. He responded, friends say, by asking her to marry him ... Freddie and Sarah exchanged vows in a Methodist church during the second week of his senior year. Seven months later, in April 1960, 17-year-old Thompson had a son."

- ^ "Fred Thompson chronology". The Tennessean. May 6, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Cottle, Michelle (December 1, 1996). "Another Beltway Bubba?". Washington Monthly. Archived from the original on May 12, 2007. Retrieved April 8, 2007.

- ^ a b c "About Fred"[usurped], via imwithfred.com (Official Site). Retrieved (July 13, 2007).

- ^ Kirkpatrick, David (July 2, 2007). "As Senator Rose, Lobbying Became Family Affair". The New York Times.

- ^ Malcolm, Andrew (September 6, 2007). "Shocking truth about Fred Thompson revealed!". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 6, 2007.

- ^ Fred Thompson Hometown Biography Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Lawrenceburg Tennessee

- ^ Fred Thompson for President in 2008

- ^ Vogel, Kenneth. "Rivals Take Aim At Thompson", CBS News (June 12, 2007). Retrieved 2007-07-08.

- ^ a b Dilanian, Ken. Past as lobbyist may play into future as candidate, USA Today (June 6, 2007).

- ^ a b "Thompson cooperated with White House during Watergate". Associated Press. March 8, 2007. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007.

- ^ a b Lowy, Joan (July 7, 2007). "Fred Thompson Aided Nixon on Watergate". The Washington Post. Associated Press. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ^ Cameron, Carl (March 8, 2007). "National TV Star, Former Republican Senator Fred Thompson Mulls '08 Presidential Bid". FoxNews. Archived from the original on June 18, 2007. Retrieved June 12, 2007.

- ^ "The Curious History of 'What Did the President Know, and when Did He Know It?' | Brennan Center for Justice". August 4, 2021.

- ^ Kranish, Michael (July 4, 2007). "Select Chronology for Donald G. Sanders". The Boston Globe.

- ^ Thompson, Fred D. (1975). At That Point in Time: The Inside Story of the Senate Watergate Committee. New York: Quadrangle/New York Times. ISBN 0-8129-0536-9. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved July 14, 2007.

- ^ "Thompson's Watergate Role Not as Advertised" by Peter Obervy. National Public Radio. Published November 5, 2007

- ^ Kranish, Michael (July 4, 2007). "Not all would put a heroic sheen on Thompson's Watergate role". The Boston Globe. pp. Sec. 1, p. 10. Archived from the original on July 15, 2007. Retrieved July 8, 2007. and "Fred Thompson Aided Nixon on Watergate". Forbes. July 4, 2007. pp. Sec. 1, p. 10. Archived from the original on July 15, 2007. Retrieved July 8, 2007.

- ^ a b Fred Rolater, Leonard Ray Blanton, Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2002. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ^ "$38,000 in 1978 → 2016 | Inflation Calculator".

- ^ a b c Locker, Richard. "Thompson tells why lobbyist pay rose with GOP-led Senate", Commercial Appeal (November 5, 1994).

- ^ Leibold, Arthur. "Some Hope for the Future After a Failed National Policy for Thrifts" in Barth, James et al. The Savings and Loan Crisis: Lessons from a Regulatory Failure, pages 58–59 (2004). Leibold cites Strunk and Case, Where Regulation Went Wrong: A Look at the Causes Behind Savings and Loan Failures in the 1980s, pages 14–16 (1988).

- ^ Vogel, Kenneth. "'Law & Order' And Lobbying", The Politico (April 2, 2007).

- ^ Becker, Jo (July 19, 2007). "Thompson lobbied for family planning". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- ^ The records show he spent much of that time in telephone conferences with the president of the group. He also spoke to administration officials on its behalf three times for a total of about three hours, but when or with whom in the administration Thompson spoke is unclear. When the work became controversial in 2007 in light of Thompson's anti-abortion stance and 2008 presidential campaign, a Thompson spokesperson said, "The [lobbying] firm consulted with Fred Thompson. It is not unusual for a lawyer to give counsel at the request of colleagues, even when they personally disagree with the issue." See Jo Becker, Records Show Ex-Senator's Work for Family Planning Unit, The New York Times, (July 19, 2007). Retrieved 2007-12-22.

- ^ David D. Kirkpatrick (July 2, 2007). "As Senator Rose, Lobbying Became Family Affair". The New York Times. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ^ Mullins, Brody. "Thompson PAC Benefits Son More Than Republicans," The Wall Street Journal (April 21, 2007).

- ^ a b c Hayes, Stephen F. (April 23, 2007). "From the Courthouse to the White House". Weekly Standard. Archived from the original on April 16, 2007. Retrieved May 2, 2007.

- ^ Powers, William. "The Politician's Pickup Lines" Archived November 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post (October 21, 1994). Some question exists about whether Thompson actually did the driving. According to Kevin Drum of the Washington Monthly, "Thompson didn't even deign to drive the thing himself." Drum, Kevin. "Fred Thompson's Red Pick-up Truck" Archived July 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Washington Monthly (2007-05-07). Retrieved 2007-06-18. Media reports in May and June 2007 said that Thompson still has the truck, which is "parked behind Thompson's mother's home outside Nashville." Chipman, Kim. "Thompson's Backers Check His `Fire in the Belly' for 2008 Race", Bloomberg (2007-06-28). According to Newsweek, "The paint is peeling and its U.S. Senate license plates expired back in 2002." Bailey, Holly. "The Sign of the Red Truck" Archived May 24, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Newsweek (2007-05-28). Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ^ Traub, James. "Party Like It's 1994", New York Times Magazine (March 12, 2006): "The Republicans shocked political professionals, including President Bill Clinton, by gaining 52 seats in the House, giving them a majority there for the first time in 40 years. (They picked up eight seats in the Senate to wrest control there, as well.)"

- ^ Heilemann, John. "The Shadow Candidates". New York Magazine. Retrieved June 18, 2007.

- ^ "United States of America Presidential Elections of 1996, Electoral College Vote by States", Psephos, Adam Carr's Election Archive.

- ^ [1] Archived July 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Fund, John (March 17, 2007). "Lights, Camera ... Candidacy?". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved April 8, 2007.

- ^ Thompson, Fred. "Additional Views of Chairman Fred Thompson, Investigation of Illegal or Improper Activities in Connection With 1996 Federal Election Campaigns, Final Report of the Committee on Governmental Affairs, Senate Report 105-167 – 105th Congress 2d Session" (March 10, 1998).

- ^ Senate Committee on Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs, History of Committee Chairmen Archived July 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved (July 13, 2007).

- ^ Sen. Thompson's Official Senate Web Site (via Archive.org).

- ^ Neal, Terry M. (August 18, 1999). "McCain Re-Emerges; Receives Thompson Endorsement". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Bush: 'The days of speculation are over'", USA Today (July 22, 2000).

- ^ Zuckerbrod, Nancy."Thompson eyed for vice presidential role" Archived October 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, via oakridger.com July 3, 2000. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ^ "How conservative is Fred Thompson?", Washington Times Editorial (June 23, 2007).

- ^ Profile at Project Vote Smart Archived July 6, 2007, at the Wayback Machine (including bio, positions, finances, interest group ratings, votes, and statements).

- ^ Theobald, Bill."In D.C., tenacious Thompson defied prediction: Reliable conservative had fierce independent streak", The Tennessean (July 8, 2007).

- ^ a b Thompson, Fred. "Federalism 'n' Me". Archived January 8, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. American Enterprise Institute (April 23, 2007). Retrieved 2007-05-13.

- ^ ""Thompson and the 'Laziness' Issue" Archived September 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine" Newsweek (September 29, 2007)

- ^ "G.O.P. Hopeful Took Own Path in the Senate" The New York Times (September 29, 2007)

- ^ Baxter, Sarah."Old Girlfriends Cast Their Vote for Thompson", Times Online (June 24, 2007).

- ^ Grove, Lloyd (July 2, 2002). "Reliable Sources". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved November 20, 2007.

- ^ Marc Santora (December 15, 2007). "A Little Thompson Humor". The New York Times. Retrieved December 24, 2007.

- ^ Brody, David (April 24, 2007). "Fred Thompson's Secret Weapon". CBNnews. Archived from the original on November 17, 2007. Retrieved November 20, 2007.

- ^ Michelle Cottle (October 22, 2007). "Jeri Rigged". The New Republic. Retrieved November 21, 2007.

- ^ Mackenzie Carpenter (August 12, 2007). "Married to ambition: Not your father's potential first spouse". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- ^ "Profile: Fred Thompson". BBC News. September 3, 2007.

- ^ Tapper, Jake."Thompson's Daughter's Death Informs Right-to-Die Stance", ABC News (October 22, 2007).

- ^ Halperin, Mark (May 24, 2007). "A New Role for Fred Thompson". Time. Archived from the original on May 26, 2007.

- ^ Birnbaum, Jeffrey. "Thompson Will Take On Outsider Role After Playing Access Man", The Washington Post, June 12, 2007

- ^ Keel, Beverly. "On screen, Thompson projects power, wisdom" Archived July 20, 2012, at archive.today, The Tennessean (May 8, 2007).

- ^ "TNT won't pull reruns starring Thompson", Seattle Times (September 1, 2007).

- ^ "Former Senator Fred Thompson in Remission for Lymphoma". Fox News. April 11, 2007. Archived from the original on April 15, 2007. Retrieved April 11, 2007.

- ^ Bloom, Mark (April 11, 2007). "Fred Thompson, GOP Potential Candidate, Had Rare NHL" Archived June 25, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. MedPage Today.

- ^ "Metro: In Brief". The Washington Post. November 26, 2002. p. B3; "Fred Thompson takes on federal council role". The Knoxville News-Sentinel. December 1, 2002. p. H3.

- ^ "Interview with Mike Boos of Citizens United". CNN. March 1, 2003.

- ^ Goldsmith, Brian. "Beware The 'Convention Candidates'", CBS News (April 20, 2007).

- ^ Thompson, Fred. "The Pitch", via YouTube. Retrieved (July 13, 2007).

- ^ Lee, Christopher (September 9, 2005). "Hill Veterans Light the Way for Nominee". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- ^ International Security Advisory Board, Former Members, State Department web site.

- ^ International Security Advisory Board, State Department web site.

- ^ Shane, Scott (February 9, 2007). "Media Censors for the Jury Let a Style Item Get Through". The New York Times.

- ^ Bohn, Kevin (February 9, 2007). "Libby trial provides a rare look inside the grand jury". CNN.

- ^ Loller, Travis. "Looking at Thompson's Lobbying Past" Archived June 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, ABC News (June 25, 2007).

- ^ Copeland, Libby and Montgomery, David. "Scooter Libby's Pals, Trusting In Providence", The Washington Post (July 3, 2007).

- ^ George W. Bush, "Statement by the President", The White House, July 2, 2007, accessed July 2, 2007.

- ^ "Political Leaders Express Outrage, Support for 'Scooter' Libby's Commuted Sentence". Fox News. July 3, 2007. Archived from the original on July 5, 2007. Retrieved July 5, 2007.

- ^ Miller, Korin. Names and Faces, The Washington Post (February 25, 2006).

- ^ The Fred Thompson Report, ABC Radio Networks.

- ^ "Fred Thompson 2007". Townhall.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ "Fred Thompson 2008". Townhall.com. Archived from the original on June 11, 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ "Fred Thompson to Speak in Richmond". WHSV TV. June 1, 2007. Retrieved June 3, 2007.

- ^ Horrigan, Marie (July 31, 2007). "Fred Thompson's Long 'Exploration' Raises Money—and Confusion". Congressional Quarterly. Archived from the original on August 14, 2007. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ "Thompson Tells Leno He Would Like to Be President". Fox News. June 7, 2007. Archived from the original on July 11, 2007. Retrieved June 28, 2007.

- ^ Nagourney, Adam. "Candidates Shift as G.O.P. Field Alters", NY Times (July 19, 2007).

- ^ Steve McGookin (September 5, 2007). "Thompson Finally Steps Onstage". Forbes. Archived from the original on September 18, 2008. Brief excerpts from the Tonight Show appearance are available from NBC Archived September 8, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. The full Tonight Show transcript is [2] Archived September 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Bill Schneider (October 16, 2007). "Poll: As Thompson's star fades, Clinton's on the rise". CNN. Retrieved October 17, 2007.

- ^ Jill Zuckman (October 10, 2007). "Thompson debuts as GOP candidates clash". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Robert D. Novak (May 7, 2007). "Let down by Fred Thompson". Washington Post. Retrieved October 17, 2007.

- ^ Nation's Oldest Right to Life Organization Supporting Thompson Standard News Wire.com, December 20. Retrieved: September 9, 2013.

- ^ Fred Thompson Receives the Endorsement of Virginia Society for Human Life Archived October 4, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Presidency Project UCSB.EDU, December 20, 2007. Retrieved: September 9, 2013.

- ^ "November 30, 2007 – Presidential Preferences". American Research Group. November 30, 2007. Retrieved December 2, 2007.

- ^ "Daily Presidential Tracking Polling History". Rasmussen Reports. December 2, 2007. Archived from the original on December 1, 2007. Retrieved December 2, 2007.

- ^ "CNN Political Ticker: Thompson drops out of GOP Presidential Race". CNN. January 22, 2008. Archived from the original on January 25, 2008. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- ^ https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/convention2008/fredthompson2008rnc.htm&ved=2ahUKEwiV37X_9f2IAxXH4MkDHRvuDqAQFnoECBUQAQ&usg=AOvVaw0iZuR5vV_HJBudZnt-Dzbo

- ^ "Fred Thompson to appear in Richmond on behalf of National Popular Vote initiative". The Washington Post. July 11, 2011. Archived from the original on October 16, 2020.

- ^ Van Gelder, Lawrence (March 26, 2008). "Fred Thompson Seeks Make-Believe Roles". The New York Times.

- ^ "Harry Woolf (Character)". IMDb.

- ^ Liz Shaw (August 29, 2009). "Brian Dennehy, Fred Thompson to star in film shooting at Crossroads Village". The Flint Journal.

- ^ Bond, Paul (March 7, 2014). "Fred Thompson Religious Thriller 'Persecuted' Gets Release Date". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ Nordyke, Kimberly (December 23, 2008). "Fred Thompson lands daily radio show". Reuters.

- ^ "Westwood says goodbye to talker Fred Thompson, welcomes Doug Urbanski". Radio-Info.com. January 4, 2011. Archived from the original on January 9, 2011.

- ^ "AAG Announces Fred Thompson as Reverse Mortgage Spokesman". reversemortgagedaily.com. May 24, 2010.

- ^ American Advisors Group (June 10, 2010). "American Advisors Group Announces Senator Fred Thompson as National Reverse Mortgage Spokesperson". prnewswire.com.

- ^ Thompson, Fred D., Teaching the Pig to Dance: A Memoir of Growing up and Second Chances, Crown Forum, 2010. ISBN 9780307460288. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- ^ US Congress "THOMPSON, Fred Dalton, (1942 - 2015)", Biographical Dictionary of the United States Congress, 1774- present. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- ^ "Fred Thompson, with larger-than-life persona, dies at 73". Tennessean.com. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ "Fred Thompson remembered as a natural actor, politician". USA Today.com. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- ^ "Fred Thompson: A Big and Joyous Life". CNN.com. November 6, 2015. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- ^ Joey Garrison, "Trump signs bill naming new Nashville federal courthouse after Thompson", The Knoxville News-Sentinel (June 7, 2017), p. 4.

- ^ "Transcript: Former Sen. Fred Thompson on 'FOX News Sunday'". Fox News. March 11, 2007. Archived from the original on May 29, 2007. Retrieved June 17, 2007.

- ^ "Exclusive! Former Tennessee Senator Fred Thompson on Possible White House Bid", Fox News Interview (June 5, 2007).

- ^ Bailey, Holly. "Away From the Cameras Archived June 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine," Newsweek (June 25, 2007).

- ^ "Thompson: Roe bad law and bad medicine". CNN. August 17, 2007. Archived from the original on August 20, 2007. Retrieved August 13, 2007.

"Nix That". The Corner. August 17, 2007. Archived from the original on September 14, 2007. Retrieved August 20, 2007. - ^ Thompson, Fred. "Armed with the Truth", ABC Radio, May 10, 2007. Accessed May 13, 2007.

- ^ Craig Fields. "Presidential Candidates And The Second Amendment". Gun Owners of America. Archived from the original on June 13, 2007. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- ^ Thompson, Fred. "Prepared Remarks for Speech to Lincoln Club Annual Dinner", ABC Radio, May 4, 2007. Accessed May 13, 2007.

- ^ YouTube. youtube.com.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: Roll Call Vote". senate.gov. January 27, 2015.

- ^ "Thompson: U.S. must rebuild military". Stiest. August 21, 2007. Retrieved October 23, 2023.

- ^ "Former Sen. Fred Thompson on 'FOX News Sunday'". Fox News. March 11, 2007. Archived from the original on May 29, 2007. Retrieved July 2, 2007.

- ^ Sean Hannity interview of Fred Thompson Archived July 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Fox News, June 6, 2007. Accessed June 9, 2007.

- ^ Thompson, Fred. "Plutonic Warming" Archived September 3, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, AEI, March 22, 2007. Accessed May 13, 2007.

External links

[edit]Official

- The Official Flickr Page for Fred Thompson (official photo site)

Documentaries, topic pages and databases

- Biography at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Financial information (federal office) at the Federal Election Commission

- Financial information (presidential campaign) at the Federal Election Commission

- OpenSecrets campaign contributions

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Archive of United States Senator Fred Dalton Thompson Congressional Website (From Internet Archive retrieved on January 3, 2007)

- Complete text and audio and video of Fred Thompson's GOP Presidential Candidacy Announcement AmericanRhetoric.com

- Complete text and audio and video of Fred Thompson's 2008 Republican National Convention Speech AmericanRhetoric.com

- Fred Dalton Thompson at IMDb

- "Fred Thompson". Find a Grave. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- Fred D. Thompson Papers Archived February 17, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, University of Tennessee Knoxville Libraries

News media

- Lawrenceburgs.com – Fred Thompson biography from hometown newspaper

- The Fred Files at NashvillePost.com: Lobbying disclosures, 1975–1994.

- Fred D. Thompson collection of news stories and commentary at The New York Times

- 1942 births

- 2015 deaths

- 20th-century American male actors

- American actor-politicians

- American Enterprise Institute

- American male film actors

- American male television actors

- American male voice actors

- American members of the Churches of Christ

- American prosecutors

- American talk radio hosts

- Deaths from cancer in Tennessee

- Deaths from lymphoma in the United States

- People from McLean, Virginia

- People from Sheffield, Alabama

- Politicians from Nashville, Tennessee

- Male actors from Tennessee

- Male actors from Alabama

- Republican Party United States senators from Tennessee

- Tennessee lawyers

- Tennessee Republicans

- United States Department of Justice lawyers

- Candidates in the 2008 United States presidential election

- United States Senate lawyers

- University of Memphis alumni

- University of North Alabama people

- Vanderbilt University Law School alumni

- Virginia Republicans

- Watergate scandal investigators

- Actors from Colbert County, Alabama

- 21st-century United States senators

- 20th-century United States senators