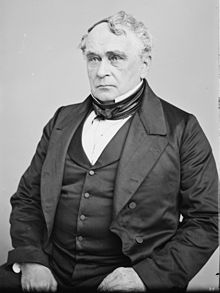

Francis Lieber

Francis Lieber | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Franz Lieber 18 March 1798 |

| Died | 2 October 1872 (aged 74) New York City, U.S. |

| Alma mater | University of Jena |

| Notable work | Lieber Code |

| Signature | |

Francis Lieber (18 March 1798 – 2 October 1872)[1][2] was a German-American jurist and political philosopher. He is best known for the Lieber Code, the first codification of the customary law and the laws of war for battlefield conduct, which served a later basis for the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 and for the later Geneva Conventions.[3][4][5] He was also a pioneer in the fields of law, political science, and sociology in the United States.[2][6]

Born in Berlin, Prussia, to a Jewish merchant family, Lieber served in the Prussian Army during the Wars of Liberation against Napoleon Bonaparte. He obtained a doctorate from the University of Jena in 1820. A republican, he volunteered to fight on the Greek side in the Greek War of Independence in 1821. After experiencing repression in Prussia for his political views, he emigrated to the United States in 1827. During his early years in America, he worked a number of jobs, including swimming and gymnastics instructor, editor of the first editions of the Encyclopaedia Americana, journalist, and translator.

Lieber wrote a plan of education for the newly founded Girard College and lectured at New York University before becoming a tenured professor of history and political economy at the University of South Carolina in 1835.[7] In 1857, he joined the faculty at Columbia University where he assumed the chair of history and political science in 1858.[7][8] He transferred to Columbia Law School in 1865 where he taught until his death in 1872.[2]

Lieber was commissioned by the U.S. Army to write the Instructions for the Government of the Armies of the United States in the Field (General Orders No. 100, 24 April 1863), the Lieber Code of military law that governed the battlefield conduct of the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865).[9][10] The Lieber Code was the first codification of the customary law and the laws of war governing the battlefield conduct of an army in the field, and later was a basis for the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 and for the Geneva Conventions.[3][11]

Life and career

[edit]Franz Lieber was born the tenth of twelve children to a wealthy Jewish merchant family in Berlin, then the capital of the Kingdom of Prussia.[12][13] The year of his birth (1798 or 1800) has been debated because he lied about his age in order to enlist.[14][2] Lieber joined the Colberg Regiment of the Prussian Army in 1815 during the Napoleonic Wars, and was wounded in Namur, Belgium during the Battle of Waterloo.[2] He was treated in a military hospital in Huy, which was then part of the Netherlands but which is today Belgium.[7][15] He rejoined his regiment after recovering from his wounds, but developed a typhoid fever and was subsequently treated at military hospitals in Aix-la-Chapelle and Cologne.[15]

After the war, he was a high school student at Graues Kloster in Berlin.[7] He became politically active during this time period, was arrested by Prussian authorities, and held for pretrial detention in Spandau prison from July to November 1819. Returning to Berlin after the Napoleonic wars (post 1815),[16] he passed the entrance exams for the University of Berlin. However, he was denied admission because of his membership in the Berliner Burschenschaft, which opposed the Prussian monarchy. Moving to Jena, Lieber entered the University of Jena in 1820 and within four months finished writing a dissertation in the field of mathematics.[17][7] As the Prussian authorities caught up with him, Lieber left Jena for Dresden to study topography with Major Decker (briefly). In Prussia, Lieber was imprisoned and repeatedly questioned for his republican views.[2]

European activities

[edit]

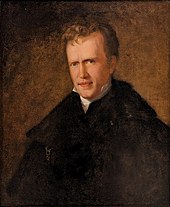

Lieber fought briefly on the Greek side in the Greek War of Independence.[2] He then spent one year, 1822–1823, in Rome tutoring the son of the Prussian ambassador, historian Barthold Georg Niebuhr.[2][7] While there, Lieber wrote about his experiences in Greece. The result was published in Leipzig in 1823 and also in Amsterdam under the title The German Anacharsis. Lieber returned to Germany on a royal pardon, but was soon imprisoned once again, this time at Köpenick. He was in pretrial detention at Köpenick from August 1824 to April 1825.[7]

At Köpenick, Lieber wrote a collection of poems entitled Wein- und Wonne-Lieder (Songs of Wine and Bliss), which on his release, with Niebuhr's help, were published in Berlin in 1824 under the pen name of "Franz Arnold". Lieber fled to England in 1825, and supported himself for a year in London by giving lessons and contributing to German periodicals. In London he met American writer and critic John Neal, who was studying gymnastics from Carl Voelker and intent on bringing the movement to the US.[18] Neal published articles in The Yankee[19] and the American Journal of Education about Lieber's work, and recommending him as "qualified, almost beyond example" as a teacher of gymnastics, and "the chief personage with professor Jahn himself".[20] Lieber also wrote a tract on the Lancasterian system of instruction, and met his future wife, Mathilda Oppenheimer.[21] He left England upon receiving an offer to manage a gymnasium and swimming program in Boston.

American educator and writer

[edit]Lieber moved to Boston in 1827. He came with recommendations from Jahn, as well as from General Pfuel who ran a swimming program in Berlin. Lieber was also acquainted with the outgoing gymnasium administrator, Charles Follen, both believing thoroughly in the importance of training the body along with the mind. Follen had established the pioneer gymnasium in 1826. Lieber's Boston swimming school of 1827, a new departure in the educational field in the United States, became such a feature that John Quincy Adams, then President of the United States, went to see it.[22][23][24] The gymnasium had a difficult time once the novelty had worn off and in the face of caricatures in the newspapers. It closed its doors after two years.[24]

In Boston, Lieber edited an Encyclopaedia Americana,[25] after conceiving of the idea of translating the Brockhaus encyclopedia into English. It was published in Philadelphia in 13 volumes, between the years 1829 and 1833.[26] At this time, he also made translations of a French work on the revolution of July 1830 and of Feuerbach's life of Kaspar Hauser. He was also a confidant to Alexis de Tocqueville on the customs of the American people. Lieber was a nationalist, supporter of free trade, racist and opponent of slavery.[2]

In 1832, he received a commission from the trustees of the newly founded Girard College to form a plan of education. This was published at Philadelphia in 1834.[26] He resided in Philadelphia from 1833 until 1835. He soon became a professor of history and political economics at South Carolina College (now the University of South Carolina), where he owned slaves until his departure in 1856.[27][28] During his 20 years at the College, he produced some of his most important works. Such writers and jurists as Mittermaier, Johann Kaspar Bluntschli, Édouard René de Laboulaye, Joseph Story and James Kent, recognized in him a kindred mind.[29] The spirit of Lieber's work is indicated in his favorite motto, Nullum jus sine officio, nullum officium sine jure ("No right without its duties, no duty without its rights").[30]

From 1856 until 1865, he was professor of history and political science at Columbia College (later Columbia University) in New York City. He chose his own title and became the first academic identified as a political scientist in the United States.[21] In 1860, he also became professor of political science at Columbia Law School, a post he held until his death. His inaugural address as professor at Columbia, on "Individualism and Socialism or Communism", was published by the college.[31]

In 1864, Lieber proposed a series of constitutional amendments.[32] These amendments proposed to abolish slavery (what would later become the 13th amendment) and guarantee equal rights regardless of race (what would later become the 14th amendment).[32] He also proposed an insurrection amendment, which was never implemented: "It shall be a high crime directly to incite to armed resistance to the authority of the United States, or to establish or to join Societies or Combinations, secret or public, the object of which is to offer armed resistance to the authority of the United States, or to prepare for the same by collecting arms, organizing men, or otherwise."[32]

Civil War activities

[edit]Lieber sided with the North during the American Civil War, even though he had been a prominent resident of South Carolina. Indeed, Lieber was even a slave owner himself, and his brothers-in-law, members of the powerful Oppenheimer (de) family dynasty, owned plantations and slaves in Puerto Rico.[27][28][33] However, in 1851, Lieber delivered an address in South Carolina warning the southern states against secession. One of his sons, geologist Oscar Montgomery Lieber (see below), joined the Confederate army and died at the Battle of Eltham's Landing. A second son, Hamilton, who had fought for the Union, lost an arm.[34]

During the conflict, Francis Lieber was one of the founders and served as the head of the Loyal Publication Society of New York, compiling news articles for dissemination among Union troops and Northern newspapers. More than one hundred pamphlets were issued by it under his supervision, of which ten were by himself. He also assisted the Union War Department and President Abraham Lincoln in drafting legal guidelines for the Union army, the most famous being General Orders Number 100, or the "Lieber Code" as it is commonly known. The Lieber Code would be adopted by other military organizations and go on to form the basis of the first Westernized laws of war. Lieber's legal legacy is detailed in the 2012 non-fiction account entitled, ironically, Lincoln's Code.[35]

An abridged version of the Lieber Code was published in 1899 in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies in 1899.[36]

Preserving Confederate documents

[edit]After the Civil War, Lieber was given the task of accumulating and preserving the records of the former government of the Confederate States of America. While working in this capacity, Lieber was one of the last known people to possess the infamous Dahlgren Affair papers. Shortly after obtaining them, Lieber was ordered to give them to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, who likely disposed of them, as they have not been seen since.

Diplomacy

[edit]From 1870 until his death in New York City, aged 72, Francis Lieber served as a diplomatic negotiator between the United States and Mexico.[37] He was chosen, with the united approval of the United States and Mexico, as final arbitrator in important cases pending between the two countries. This work was not completed at his death.[26] Lieber was a member of the French Institute and of many learned societies in the United States and elsewhere.[25]

Personal life

[edit]He was married to Mathilde Oppenheimer, the daughter of a Hamburg merchant-banker.[7] They met in London in 1826 where Lieber was her tutor.[7] They married in New York City in 1829.[7] They had four children, one of whom died in infancy.[7] His son Oscar Montgomery Lieber was a geologist. During the Civil War, he was killed in action serving as a private in the Confederate army.

A second son, Alfred Hamilton Lieber (7 June 1835, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 18 October 1876, Baden-Baden, Germany), entered the volunteer army at the beginning of the civil war as 1st lieutenant, 9th Illinois Regiment, and was badly wounded at Fort Donelson. Afterward, he was appointed a captain in the veteran reserve corps, and served during the draft riots in New York City in 1863. In 1866, he was made a captain and military storekeeper in the regular army, and was retired on account of disabilities contracted in the line of duty.

A third son, Guido Norman Lieber, was a United States Army lawyer and jurist. During the Civil War, he served in the Union army and later rose to the rank of Brigadier General[7] and also became Judge Advocate General of the United States Army--serving the longest-ever tenure as head of the Advocate General's Department (1884–1901).

Lieber expressed hostile sentiment to the French, Turks and Russians. He wrote in 1854, "I do not like the Turks, they are a coarse race, without a history" and "I nourish a very strong hatred for the Russians."[15]

Influence

[edit]In 2015, the United States Department of Defense published its Law of War Manual. Lieber is cited after Hugo Grotius and Emer de Vattel and before Hersch Lauterpacht as a subsidiary means and an authority in determining the rules of law of war.[38]

Works

[edit]- Notes on the Fallacies of American Protectionists (PDF) (4th ed.). New York: American Free Trade League. 1870.

- Encyclopaedia Americana (Editor, 1829–1851)

- The Stranger in America (2 vols., 1833–35)

- Letters to a Gentleman in Germany, written after a Trip from Philadelphia to Niagara (1834)

- Reminiscences of an intercourse with Mr. Niebuhr, the historian, during a residence with him in Rome, in the years 1822 and 1823. Philadelphia: Carey, Lea & Blanchard. 1835.

- A Manual of Political Ethics (2 vols. 8vo, Boston, 1838), adopted by Harvard College as a text book, and commended by Kent and Story

- Legal and Political Hermeneutics, or Principles of Interpretation and Construction in Law and Politics (1838)

- International Copyright. Wiley & Putnam. 1840.

- Laws of Property: Essays on Property and Labor (18mo, New York, 1842)

- Great events: described by distinguished historians, chroniclers, and other writers. New York: Harper. 1847.

- The West and Other Poems (1848)

- On Civil Liberty and Self-Government. Philadelphia, J.B. Lippincott & Co. 1874.(2 vols. 12mo, Philadelphia, 1853; new ed., 1874)

- "Guerrilla Parties Considered with Reference to the Laws and Usages of War". The Miscellaneous Writings of Francis Lieber. Vol. 2. London: Lippincott and Co. 1881 [1862]. pp. 275–92. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- "General Orders No. 100 : The Lieber Code: Instructions for the Government of Armies of the United States, in the Field". Yale Law School: Avalon Project. 1863. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- Amendments of the Constitution Submitted to the Consideration of the American People. New York: Loyal Publication Society. 1865. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- Reflections on the changes which may seem necessary in the present constitution of the state of New York. New York: The New York Union League Club. 1867.

- Memorial relative to the Verdicts of Jurors (1867)

- The Unanimity of Juries (1867)

- Fragments of Political Science on Nationalism and Internationalism. New York, Scribner. 1868.

Writings on penal legislation

[edit]- "Essays on Subjects of Penal Law and the Penitentiary System," published by the Philadelphia prison discipline society

- "Abuse of the Pardoning Power," republished by the legislature of New York

- "Remarks on Mrs. Fry's Views of Solitary Confinement," published in England

- Letter on the Penitentiary System. 1838. published by the legislature of South Carolina

Occasional papers

[edit]- "Letter on Anglican and Gallican Liberty"

- a paper on the vocal sounds of Laura Bridgman, the blind deaf mute, compared with the elements of phonetic language, published in the "Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge"

- "Individualism and Socialism or Communism" His inaugural address as professor in Columbia College. He regarded these as the two poles on which all human life turns.

- "The Ancient and the Modern Teacher of Politics" His introductory discourse to a course of lectures on the state in the college law school.

Numerous addresses on anniversary and other occasions.

Translations

[edit]- Ramshorn, Lewis (1841). Dictionary of Latin Synonymes. Little and Brown.

- Gustave de Beaumont; Alexis de Tocqueville (1848). Penitentiary System in the United States. With annotations. He also assisted in the gathering of the statistical data for the original book.[21]

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Francis Lieber | German-American, Political Scientist, Educator | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Vile, John R. (1998). "Francis Lieber and the Process of Constitutional Amendment". The Review of Politics. 60 (3): 525–543. doi:10.1017/S0034670500027455. ISSN 0034-6705. JSTOR 1407987.

- ^ a b Kinsella, Helen M. (2022). "Settler Empire and the United States: Francis Lieber on the Laws of War". American Political Science Review. 117 (2): 629–642. doi:10.1017/S0003055422000569. ISSN 0003-0554. S2CID 251432573.

- ^ Davis, George B. (1907). "Doctor Francis Lieber's Instructions for the Government of Armies in the Field". American Journal of International Law. 1 (1): 13–25. doi:10.2307/2186282. ISSN 0002-9300. JSTOR 2186282.

- ^ Nys, Ernest (1911). "Francis Lieber — His Life and His Work: Part II". American Journal of International Law. 5 (2): 355–393. doi:10.2307/2186723. ISSN 0002-9300. JSTOR 2186723.

- ^ Small, Albion W. (1916). "Fifty Years of Sociology in the United States (1865-1915)". American Journal of Sociology. 21 (6): 727–728. doi:10.1086/212570. ISSN 0002-9602. JSTOR 2763629.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "CV Franz/Francis Lieber (1798–1872) and Mathilde Lieber née Oppenheimer (1805–1890)", A Sea of Love, Brill, 2 July 2018, ISBN 978-90-04-34425-9, retrieved 24 December 2023

- ^ "1857". Department of History - Columbia University. 13 November 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

- ^ Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Instructions for the Government of the Armies of the United States in the Field (1 ed.). New York: D.Van Nostrand. 1863. Retrieved 23 August 2015 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Sheehan-Dean, Aaron. The American Civil War: Total or Just?. Teachinghistory.org, accessed 18 December 2011.

- ^ Society, American Jewish Historical (1901). Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society. American Jewish Historical Society.

- ^ "The Lieber Collection". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ Francis Lieber. Hermenutics and Practical Reason. John Catalano University Press of America. 2000

- ^ a b c Nys, Ernest (1911). "Francis Lieber —His Life and His Work: Part I". American Journal of International Law. 5 (1): 84–117. doi:10.2307/2186767. ISSN 0002-9300. JSTOR 2186767.

- ^ Harley, Lewis R (January 1898). "Sketch of Francis Lieber". Popular Science Monthly. 52: 407. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ Francis Lieber. Hermenutics and Practical Reason. John Catalano University Press of America. 2000. p. 2.

- ^ Sears, Donald A. (1978). John Neal. Boston, Massachusetts: Twayne Publishers. p. 106. ISBN 080-5-7723-08.

- ^ Barry, William D. (20 May 1979). "State's Father of Athletics a Multi-Faceted Figure". Maine Sunday Telegram. Portland, Maine. pp. 1D – 2D.

- ^ Leonard, Fred Eugene (1923). A Guide to the History of Physical Education. Philadelphia and New York: Lea & Febiger. p. 240.

- ^ a b c Farr, James (1999). "Lieber, Francis". American National Biography (online ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1400365.

- ^ Albert Berhardt Faust, The German Element in the United States (2 vols.), Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1909, v. 2, chap. 5, p. 216.

- ^ Feintuch, Burt; Watters, David H., eds. (2005). The Encyclopedia of New England. Yale University Press. p. 282.

- ^ a b Leonard, Fred Eugene (1923). A Guide to the History of Physical Education. Philadelphia and New York: Lea & Febiger. pp. 239–242.

- ^ a b Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- ^ a b c One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Ripley, George; Dana, Charles A., eds. (1879). . The American Cyclopædia.

- ^ a b "A Tale of Two Columbias: Francis Lieber, Columbia University and Slavery | Columbia University and Slavery". columbiaandslavery.columbia.edu. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ a b Keil, Hartmut (2008). "Francis Lieber's Attitudes on Race, Slavery, and Abolition". Journal of American Ethnic History. 28 (1): 13–33. doi:10.2307/27501879. ISSN 0278-5927. JSTOR 27501879. S2CID 254496072.

- ^ Betsy [Baker] Röben, Johann Caspar Bluntschli, Francis Lieber und das moderne Völkerrecht 1861–1881, Nomos Press, Baden-Baden 2003, with English summary: Johann Caspar Bluntschli, Francis Lieber and Modern International Law, 1861–1881, xii, 356 pp.

- ^ Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- ^ Lieber, Francis (1858). "Inaugural Address". Addresses of the Newly-Appointed Professors of Columbia College. New York: By the Authority of the Trustees. pp. 55-116. Retrieved 20 April 2018 – via Internet Archive.

Francis Lieber.

- ^ a b c Lepore, Jill (4 December 2023). "What Happened When the U.S. Failed to Prosecute an Insurrectionist Ex-President". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X.

- ^ Freidel, Frank (1947). Francis Lieber, Nineteenth-century Liberal. Louisiana State University Press.

- ^ Lepore, Jill (8 December 2023). "What Happened When the U.S. Failed to Prosecute an Insurrectionist Ex-President". The New Yorker. p. 15.

- ^ Witt, John Fabian (2012). Lincoln's Code: The Laws of War in American History. New York, NY: Free Press, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4165-7012-7.

- ^ United States. War Department. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series 2. Vol. 5. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1899, pp. 671-682.

- ^ Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1892). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- ^ Preston, Stephen E.; Taylor, Robert S. (2016). Department of Defense Law War Manual (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: Department of Defense. p. 35. Retrieved 19 April 2018 – via Defense Technical Information Center.

References

[edit]- Thayer, Martin Russell (1882). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (9th ed.).

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 590.

- Vincent, John Martin (1933). "Lieber, Francis". Dictionary of American Biography. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1892). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

Further reading

[edit]- Carnahan, Burrus (2007). Act of Justice: Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation and the Law of War. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky.

- Dilbeck, D. H. " 'Responsible to One Another and to God”: Why Francis Lieber Believed the Union War Must Remain a Just War" in New Perspectives on the Union War edited by Gary W. Gallagher and Elizabeth R. Varon (Fordham UP, 2019) pp. 143–159 online

- Ebeling, Richard M., "Francis Lieber's America and the Politics of Today," Future of Freedom Foundation, November 1, 2020

- Freidel, Francis (1947). Francis Lieber: Nineteenth-Century Liberal.

- Daniel Coit Gilman, ed. (1881). Miscellaneous Writings by Francis Lieber. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott.

- Vol. 1: Reminiscences, Addresses and Essays

- Vol. 2: Contributions to Political Science (contains a biography)

- Harley, Lewis R. (1899). Francis Lieber: His Life and Political Philosophy. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Mack, Charles R.; Lesesne, Henry H., eds. (2005). Francis Lieber and the Culture of the Mind. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-535-7.

- Thomas Sergeant Perry, ed. (1882). The Life and Letters of Francis Lieber. Boston: John R. Osgood and Co.

- Root, Elihu (July 1913). "Francis Lieber". American Journal of International Law. 7 (3): 453–469. doi:10.2307/2187428. JSTOR 2187428. S2CID 246010401.

- Witt, John Fabian (2012). Lincoln's Code: The Laws of War in American History. New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-1-4165-7012-7.

External links

[edit]- Works by Francis Lieber at Project Gutenberg

- Harley, Lewis R. (January 1898). . Popular Science Monthly. Vol. 52.

- Biography from Yale Dictionary of American Legal Biography

- Francis Lieber on the Sources of Civil Liberty by Steven Alan Samson

- Thayer, Martin Russell (1882). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. XIV (9th ed.).

- "The Laws of War: From the Lieber Code to the Brussels Conference," by Peter Holquist, Berlin Journal, Jan. 2019

- Works by or about Francis Lieber at the Internet Archive

- 1798 births

- 1872 deaths

- 19th-century American economists

- 19th-century American Jews

- 19th-century American male writers

- 19th-century American non-fiction writers

- American economists

- American gymnasts

- American male non-fiction writers

- American people of German-Jewish descent

- American political philosophers

- American political scientists

- Columbia University faculty

- German economists

- German gymnasts

- Jewish American economists

- Jewish American non-fiction writers

- American slave owners

- Jewish philosophers

- New York University faculty

- People from the Margraviate of Brandenburg

- People of the Battle of Waterloo

- People of New York (state) in the American Civil War

- Presidents of the University of South Carolina

- Prussian Army personnel of the Napoleonic Wars

- Prussian emigrants to the United States

- Southern Unionists in the American Civil War

- Sportspeople from Berlin

- University of Jena alumni

- University of South Carolina faculty