Frank J. Sprague

Frank J. Sprague | |

|---|---|

Frank Julian Sprague (1857-1934) American inventor, Father of Electric Traction | |

| Born | July 25, 1857 |

| Died | October 25, 1934 (aged 77) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | United States Naval Academy |

| Known for | Electric motor |

| Awards | IEEE Edison Medal |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Electrical engineering |

Frank Julian Sprague (July 25, 1857 in Milford, Connecticut - October 25, 1934) was an American naval officer and inventor who contributed to the development of the electric motor, electric railways, and electric elevators. His contributions were especially important in promoting urban development by increasing the size cities could reasonably attain (through better transportation) and by allowing greater concentration of business in commercial sections (through use of electric elevators in skyscrapers). He became known as the "Father of Electric Traction".

Childhood, education

Sprague was born in Milford, Connecticut in 1857. He attended Drury High School in North Adams, Massachusetts and excelled in mathematics. In 1874, he won an appointment to the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. There, he graduated seventh in the Class of 1878.

U.S. Navy, inventor

He was commissioned as an ensign in the U.S. Navy. During his ensuing naval service, he first served on the USS Richmond, then the USS Minnesota. While his ship was in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1881, Sprague invented the inverted type of dynamo. After he was transferred to the USS Lancaster, flagship of the European Squadron, he installed the first electric call-bell system on a U.S. Navy ship. Sprague took leave to attend the Paris Electrical Exhibition in 1881 and the Crystal Palace Exhibition in Sydenham, England in 1882, where he was on the jury of awards for gas engines, dynamos and lamps.

Joining the emerging electrical industry

In 1883, Edward H. Johnson, a business associate of Thomas Edison, persuaded Sprague to resign his naval commission to work for Edison. One of Sprague's significant contributions to the Edison Laboratory at Menlo Park, New Jersey was the introduction of mathematical methods. Prior to his arrival, Edison conducted many costly trial-and-error experiments. Sprague's approach was to calculate using mathematics the optimum parameters and thus save much needless tinkering. He did important work for Edison, including correcting Edison's system of mains and feeders for central station distribution. In 1884, he decided his interests in the exploitation of electricity lay elsewhere, and he left Edison to found the Sprague Electric Railway & Motor Company.

By 1886, Sprague's company had introduced two important inventions: a constant-speed, non-sparking motor with fixed brushes, and a method to return power to the main supply systems of equipment driven by electric motors. His new motor was the first to maintain constant revolutions per minute under different loads. It was immediately popular, and was endorsed by Edison as the only practical electric motor available. His method of returning power to main supply systems was important in the development of the electric train and the electric elevator.

Richmond: inventing the trolley-pole

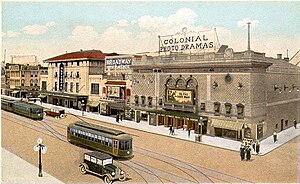

Sprague's inventions included a system on streetcars for collecting electricity from overhead wires. His spring-loaded trolley pole, invented in 1880,[1] used a wheel to travel along the wire. In late 1887 and early 1888, using his trolley system, Sprague installed the first successful large electric street railway system, the Richmond Union Passenger Railway in Richmond, Virginia. Long a transportation obstacle, the hills of Richmond included grades of over 10%, and were an excellent proving ground for acceptance of his new technology in other cities.

Within a year, electric power had replaced more costly horsecars in many cities. By 1889 110 electric railways incorporating Sprague's equipment had been begun or planned on several continents. In 1890, Edison, who manufactured most of Sprague's equipment, bought him out, and Sprague turned his attention to electric elevators.

Electric elevators

While electrifying the streetcars of Richmond, the increased passenger capacity and speed gave Sprague the notion that similar results could be achieved in vertical transportation: electric elevators. He saw that increasing the capacity of elevator shaft ways would not only save passengers' time, but would also increase the earnings of tall buildings, the heights of which were limited by the total floor space taken up in the shaft ways by slow-running hydraulic-powered elevators.

In 1892, Sprague founded the Sprague Electric Elevator Company, and with Charles R. Pratt developed the Sprague-Pratt Electric Elevator. The company developed floor control, automatic elevators, acceleration control of car safeties and a number of freight elevators. The Spague-Pratt elevator ran faster and with bigger loads than hydraulic or steam elevators, and 584 elevators had been installed worldwide. Sprague then sold his company to the Otis Elevator Company in 1895.

Multiple unit train controls

Sprague's experience with elevator control led him to devise a multiple unit system of electric railway operation, which accelerated the development of electric traction. In the multiple unit system, each car of the train carries electric traction motors. By means of relays energized by train-line wires, the engineer (or motorman) commands all of the traction motors in the train to behave in unison. For lighter trains there is no need for locomotives, so every car in the train can generate revenue; where locomotives are used, one person can control all of them.

Sprague's first multiple unit order was from the South Side Elevated Railroad (the first of several elevated railways in locally known as the "L") in Chicago, Illinois. The success there was quickly followed by substantial multiple-unit contracts in Brooklyn, New York and Boston, Massachusetts.

New York: Grand Central, elevators in skyscrapers

From 1896 to 1900 Sprague served on the Commission for Terminal Electrification of the New York Central Railroad, including the Grand Central Terminal in New York City, where he designed a system of automatic train control to ensure compliance with trackside signals. He founded the Sprague Safety Control & Signal Corporation to develop and build this system.

During World War I, Sprague served on the Naval Consulting Board. Then, in the 1920s, he devised a method for safely running two independent elevators, local and express, in a single shaft, to conserve floor space. He sold this system, along with systems for activating elevator car safety systems when acceleration or speed became too great, to the Westinghouse Company.

Heritage, awards

The effect of Sprague's developments in electric traction was to permit an expansion in the size of cities, while his development of the elevator permitted greater concentration in cities' commercial sections and increased the profitability of commercial buildings. Sprague's inventions over 100 years ago made possible modern light rail and rapid transit systems which still function on the same principles today.

Sprague was awarded the gold medal at the Paris Electrical Exhibition in 1889, the grand prize at the St. Louis Exhibition in 1904, the Elliott-Cresson Medal in 1904, the Edison Medal of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, now IEEE, in 1910 'For meritorious achievement in electrical science, engineering and arts as exemplified in his contributions thereto', the Franklin Medal in 1921 and the John Fritz Gold Medal (posthumously) in 1935.

"All through his life and up to his last day, Frank Sprague had a prodigious capacity for work," his son Robert wrote in 1935. "And once having made up his mind on a new invention or a new line of work, he was tireless and always striving for improvement. He had a brilliantly alert mind and was impatient of any half-way compromise. His interest in his work never ceased; only a few hours before the end, he asked to have a newly designed model of his latest invention brought to his bedside."

Frank and Harriet Sprague had two sons, Robert and Julian.

After Sprague died in 1934, his widow Harriet turned over a substantial amount of material from his collection to the New York Public Library, where it remains today accessible to the public via the rare books division. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia, and she was interred beside him after her death in 1969.

In 1959, Harriet Sprague had donated funds for the Sprague Building at the Shore Line Trolley Museum at East Haven, Connecticut, not far from Sprague's boyhood home in Milford. The museum is the oldest operating trolley museum in the United States, and has one of the largest collections of trolley artifacts in the United States.

In 1999, two of Frank and Harriet's grandsons, John L. Sprague and Peter Sprague, cut the ribbon and started an 1884 Sprague motor at a new exhibit at the Shore Line Trolley Museum. There, a new permanent exhibit, "Frank J. Sprague: Inventor, Scientist, Engineer", will be available to help tell the story of the part electricity played in the growth of cities as well as the role of the Father of Electric Traction.