Frère Jacques

| "Frère Jacques" | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nursery rhyme | |

| Language | French |

| English title | "Brother John" |

| Songwriter(s) | Traditional |

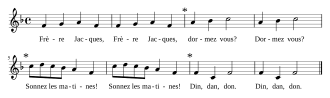

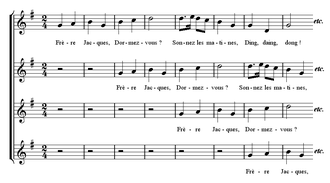

"Frère Jacques" (/ˌfrɛərə ˈʒɑːkə/, French: [fʁɛʁ(ə) ʒak]), also known in English as "Brother John", is a nursery rhyme of French origin. The rhyme is traditionally sung in a round.

The song is about a friar who has overslept and is urged to wake up and sound the bell for the matins, the midnight or very early morning prayers for which a monk would be expected to awake.

Lyrics

Frère Jacques, Frère Jacques,

Dormez-vous? Dormez-vous?

Sonnez les matines! Sonnez les matines!

Din, din, don. Din, din, don.[1]

English translation

Brother Jacques, Brother Jacques,

Are you sleeping? Are you sleeping?

Ring/Sound [the bells for] matins! Ring [the bells for] matins!

Ding, ding, dong. Ding, ding, dong.

Traditional English lyrics

Are you sleeping? Are you sleeping?

Brother John, Brother John,

Morning bells are ringing! Morning bells are ringing!

Ding, dang, dong. Ding, dang, dong.[2]

The song concerns a monk's duty to ring the morning bells (matines). Frère Jacques has apparently overslept; it is time to ring the morning bells, and someone wakes him up with this song.[3] The traditional English translation preserves the scansion, but alters the meaning such that Brother John is being awakened by the bells.

In English, the word friar is derived from the Old French word frere (Modern French frère; "brother" in English), as French was still widely used in official circles in England during the 13th century when the four great orders of Friars started. The French word frère in turn comes from the Latin word frater (which also means "brother").[4]

The French name Jacques would not ordinarily be translated to "John", which is "Jean" in French. The name Jacques, instead, corresponds to the English names James or Jacob, which derive from the Latin Iacobus and the Greek Ἰακώβος (Septuagintal Greek Ἰακώβ), referring to the Biblical Patriarch Jacob and the apostles known in English as James.

Theories of origin

A possible connection between "Frère Jacques" and the 17th century lithotomist Frère Jacques Beaulieu (also known as Frère Jacques Baulot[5][6]), as claimed by Irvine Loudon[7] and many others, was explored by J. P. Ganem and C. C. Carson[8] without finding any evidence for a connection.

Martine David and A. Marie Delrieu suggest that "Frère Jacques" might have been created to mock the Dominican friars, known in France as the Jacobin order, for their sloth and comfortable lifestyles.[9]

In a review of a book about Kozma Prutkov, Richard Gregg, professor of Russian at Vassar College, notes that the satirical collective pseudonym Prutkov claimed "Frère Jacques" was derived from a Russian seminary song about a "Father Theofil".[10]

Published record

First publication

AllMusic states[11] that the earliest version of the melody is on a French manuscript circa 1780 (manuscript 300 in the manuscript collection of the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris). The manuscript is titled "Recueil de Timbres de Vaudevilles", and the Bibliothèque Nationale estimates that it was written between 1775 and 1785. The "Frère Jacques" melody is labelled "Frère Blaise" in this manuscript.

Sheet music collector James Fuld (1916–2008) states that the tune was first published in 1811,[12] and that the words and music were published together in Paris in 1869.[13] An earlier publication in 1825 included the words together with a description of the melody in solfège, but not in musical notation.[14] The words and music appear together in Recreations de l'enfance: Recueil de Rondes avec Jeux et de Petites Chansons pour Faire Jouer, Danser et Chanter les Enfants avec un Accompagnement de Piano Très-Facile by Charles Lebouc, which was first published in 1860 by Rouart, Lerolle & Cie. in Paris. This book was very popular and was republished several times, so many editions exist.

French musicologist Sylvie Bouissou has found some evidence that composer Jean-Philippe Rameau had written the music. A manuscript at the French National Library contains "Frère Jacques" among 86 canons, with Rameau listed as author.[15]

In 1926, the tune was used in a patriotic anthem written by officers of the Chinese Whampoa Military Academy, "Revolution of the Citizens" (国民革命歌).[16]

Comparison with Fra Jacopino

"Frère Jacques" bears resemblance to the piece Toccate d'intavolatura, No. 14, Capriccio Fra Jacopino sopra L'Aria Di Ruggiero composed by Girolamo Frescobaldi,[17] which was first published around 1615[18]—"Fra Jacopino" is one potential Italian translation for "Frère Jacques".[19] Edward Kilenyi pointed out that "Fra Jacopino" shares the same "Frère Jacques"-like melody as "Chanson de Lambert", a French song dating from 1650, and a Hungarian folk tune.[20]

The "Frère Jacques" tune is one of the most basic repeating canons along with the melody of "Three Blind Mice". It is also simple enough to have spread easily from place to place. For example, Barbara Mittler in a conference abstract points out that the melody of "Frère Jacques" is so thoroughly assimilated into Chinese culture that it might be widely regarded as a Chinese folksong in China called "Two Tigers".[21]

Influence

Science

- In the fields of chemistry and cheminformatics, the circuit rank of a molecular graph (the number of rings in the smallest set of smallest rings) is sometimes referred to as the Frèrejacque number.[22][23][24]

Popular culture

- A version of the tune appears in the third movement of the Symphony No. 1 by Gustav Mahler. Mahler presents the melody in a minor key instead of a major key, thus giving the piece the character of a funeral march or dirge; however, the mode change to minor might not have been an invention by Mahler, as is often believed, but rather the way this round was sung in the 19th century and early 20th century in Austria.[25][26] Francesca Draughon and Raymond Knapp argue[27] that Mahler had changed the key to make "Frère Jacques" sound more "Jewish" (Mahler converted to Catholicism from Judaism). Draughon and Knapp claim that the tune was originally sung to mock non-Catholics, such as Protestants or Jews. Mahler himself called the tune by its German name, "Bruder Martin", and made some allusions to the piece being related to a parody in the programs he wrote for the performances.[28] Interpretations similar to this are quite prevalent in academia and in musical circles.[29]

- Leonard Bernstein made use of the song to illustrate counterpoint in his television program What Makes Music Symphonic?[30][31] (one of a series of 53 programs, the Young People's Concerts with the New York Philharmonic, combining music and lectures that were televised between 1959 and 1972).

- The Beatles' 1966 song ”Paperback Writer" features the title "Frère Jacques" sung by John Lennon and George Harrison under the main melody of the last verse.[32]

- The French performer known as Le Pétomane entertained live audiences in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with his own unique rendition, according to the BBC.[33]

- Henri Bernstein, a French playwright, wrote a comedic play entitled Frère Jacques (translated as Brother Jacques) with Pierre Veber in 1904.[34][35]

- Frère Jacques is a type of semi-soft cow's milk cheese with a mild hazelnut taste, produced by Benedictine monks from the Saint-Benoit-du-lac Abbey in Quebec, Canada.[36]

- Four French singers, brothers André and Georges Bellec, François Soubeyran and Paul Tourenne formed a comedic singing group in 1944 known as Les Frères Jacques, even though none of them were named "Jacques". The group name was a bit of a play on words since a common French expression, "faire le jacques", means to act like a clown. They had successful careers over the next few decades.[37]

- The demonstrators in Tiananmen Square chanted political slogans to the tune of "Frère Jacques".[38]

- There is a strong oral tradition among children in China, Vietnam and other places in Asia of passing on songs with their own lyrics, sung to the tune of "Frère Jacques".[39]

- Frère Jacques is the name of a chain of franchised French restaurants in the UK[40] and the name of a French restaurant in the Murray Hill section of New York City.[41] Les Frères Jacques is the name of a French restaurant in Dublin.[42]

- Ron Haselden, a British artist living in the French town of Brizard, in Brittany, has produced an interactive multimedia piece featuring "Frère Jacques" in collaboration with Peter Cusack.[43]

- The Chinese song "Dadao lie qiang" ("Cut down the great powers", or rather: "Let's beat together the great powers", also known as 'The "Revolution of the Citizens" Song') celebrates the cooperation in China in the 1920s of Mao Zedong's Chinese Communist Party and the Kuomintang against warlords and imperialist powers, and is sung to the tune of "Frère Jacques".[44]

- K-pop group Nmixx interpolates the rhyme into their 2023 song "Young, Dumb, Stupid".[45]

- The Beach Boys' song "Surf's Up" references the English version of "Frère Jacques', both lyrically and melodically, in the song's line, "Are you sleeping, brother John?"[46]

References

- ^ "Frère Jacques", partitions-domaine-public.fr

- ^ "Brother John", partitions-domaine-public.fr

- ^ Landes, David S. (1998). The Wealth and Poverty of Nations. New York: W. W. Norton. p. 48. ISBN 9780393040173.

- ^ "friar". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Jacques Baulot, beaufort39.free.fr (in French)

- ^ Bourdin, E. (1917). Un célèbre lithotomiste franc-comtois: Jacques Baulot dit Frère Jacques (1651–1720). Besançon.

- ^ Loudon, Irvine (2001). Western Medicine. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924813-3.

- ^ Ganem, J. P.; Carson, C. C. (April 1999). "Frère Jacques Beaulieu: from rogue lithotomist to nursery rhyme character". The Journal of Urology. 161 (4): 1067–1069. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(01)61591-x. PMID 10081839.

- ^ Refrains d'enfants, histoire de 60 chansons populaires, Martine David, A. Marie Delrieu, Herscher, 1988.

- ^ Gregg, Richard (June 1974). "Review of Koz'ma Prutkov: The Art of Parody by Barbara Heldt Monter". Slavic Review. 33 (2): 401–402. doi:10.2307/2495856. JSTOR 2495856. S2CID 165132644.

- ^ Robert Cummings. Frère Jacques (Are You Sleeping), traditional children's song (a.k.a. Bruder Jakob) at AllMusic

- ^ La Cle du Caveau a l'usage de tous les Chansonniers francais, Paris, 1811

- ^ Fuld, James J. (1995). The Book of World Famous Music Classical, Popular, and Folk. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-28445-X.

- ^ Paris, Aimé (1825). Expositions et pratique des procédés de la mnemotechniques, à l'usage des personnes qui veulent étudier la mnémotechnie en général. Paris. pp. 502–505.

- ^ "Frère Jacques" a été composé par Jean Philippe Rameau

- ^ 《两只老虎》改编的民国军歌 Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine [The military song of the Republic of China adapted from "Two Tigers"], qingdaonews.com, 31 March 2014 (in Chinese)

- ^ Frescobaldi: Harpsichord Works, composer: Jacques Arcadelt, Girolamo Frescobaldi; Performer: Louis Bagger. Audio CD (August 28, 2001)

- ^ Frescobaldi: Toccate & Partite, Libro Primo, Todd M. McComb

- ^ "Fra Jacopino" has additional historical importance. The half note and quarter note are reported at ""Half Note", Bartleby.com". Archived from the original on 2006-09-16. Retrieved 2017-12-31. to have first appeared in Frescobaldi's publication of "Fra Jacopino". [clarification needed]

- ^ Kilenyi, Edward (January 1919). "The Theory of Hungarian Music". The Musical Quarterly. 5 (1): 20–39. doi:10.1093/mq/v.1.20.

- ^ "From Mozart to Mao to Mozart – Western Music in Modern China", Barbara Mittler, Rethinking Cultural Revolution Culture, (workshop) Heidelberg, 22–24 February 2001

- ^ May, John W.; Steinbeck, Christoph (2014). "Efficient ring perception for the Chemistry Development Kit". Journal of Cheminformatics. 6 (3): 3. doi:10.1186/1758-2946-6-3. PMC 3922685. PMID 24479757.

- ^ Downs, G.M.; Gillet, V.J.; Holliday, J.D.; Lynch, M.F. (1989). "A review of Ring Perception Algorithms for Chemical Graphs". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 29 (3): 172–187. doi:10.1021/ci00063a007.

- ^ Frèrejacque, Marcel (1939). "No. 108-Condensation d'une molecule organique" [Condenstation of an organic molecule]. Bulletin de la Société Chimique de France. 5: 1008–1011.

- ^ Reinhold Schmid: 50 Kanons. Vienna, n.d. [ca. 1950] (Philharmonia pocket scores No. 86)

- ^ Ute Jung-Kaiser: "Die wahren Bilder und Chiffren 'tragischer Ironie' in Mahlers 'Erster' " In: Günther Weiß (ed.): Neue Mahleriana: essays in honour of Henry-Louis de LaGrange on his seventieth birthday. Lang, Berne etc. 1997, ISBN 3-906756-95-5. pp. 101–152

- ^ Mahler and the Crisis of Jewish Identity Archived 2002-03-14 at the Wayback Machine by Francesca Draughon and Raymond Knapp, Echo volume III, issue 2 (Fall 2001)

- ^ Symphony No. 1 in D major Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine, Composer: Gustav Mahler, Program note originally written for the following performance: National Symphony Orchestra: Leonard Slatkin, conductor; Dotian Levalier, harp; Mahler's First Symphony June 7–9, 2007, Richard Freed

- ^ "Mahler's Music", Dean Olsher, of NPR's Morning Edition, July 31, 1998, discusses jazz musician and composer Uri Caine's reinterpretations of Mahler.

- ^ What Makes Music Symphonic? (1958) at IMDb , Leonard Bernstein

- ^ Young People's Concerts, Leonard Bernstein, 1958

- ^ MacDonald, Ian (2005). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties (2nd rev. ed.). London: Pimlico. p. 196. ISBN 1-84413-828-3.

- ^ "You don’t see many of those these days", Joker – Trivia, Follow your Dream, BBC

- ^ Columbia Dictionary of Modern European Literature, edited by Jean-Albert Bédé, William Benbow Edgerton, Columbia University Press, 1980.[page needed]

- ^ Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature, Merriam-Webster, Encyclopædia Britannica, ISBN 0-87779-042-6, 1995.[page needed]

- ^ Saint Benedict-du-Lac Abbey, Quebec, Canada website.

- ^ Les Frères Jacques Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine, Biography, RFI Musique, March 2004

- ^ "Comrade Jiang Zemin does indeed seem a proper choice", Jasper Becker, London Review of Books, Vol. 23 No. 10, 24 May 2001

- ^ "Eating the mosquito: Transmission of a Chinese children's folksong", David Seubert, CHINOPERL Papers, vol. 16 1992. pp. 133–143. ISSN 0193-7774

- ^ "About Frères Jacques" Archived 2007-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, Frères Jacques Restaurant-Bar-Cafe, a UK franchised restaurant chain (depuis 1994)

- ^ Hello and Welcome to the Frère Jacques Website Archived 2008-02-17 at the Wayback Machine, Frère Jacques Restaurant, Murray Hill section of New York City

- ^ Les Frères Jacques, Dublin, Ireland Archived 2005-05-16 at the Wayback Machine restaurant review

- ^ Frère Jacques et autres pièces à Francis: Expositions. 1997. Saint-Fons Ron Haselden, Saint-Fons, Centre d'Arts Plastiques, 1997, ISBN 2-9509357-2-9

- ^ Une utilisation insolite de la musique de l'Autre, Pom pom pom pom: Musiques et caetera Neuchatel: Musee d'Ethnographie 1997 pp. 227–241.

- ^ Gladys Yeo (13 March 2023). "NMIXX share joyful music video for new song 'Young, Dumb, Stupid'". NME. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ "The Beach Boys: Surf's Up". www.songfacts.com.