Fort Gregg-Adams

| Fort Gregg-Adams | |

|---|---|

| Petersburg and Tri-cities Area | |

Shoulder sleeve insignia and emblems of units or agencies stationed at Fort Gregg-Adams | |

| Coordinates | 37°14′06″N 77°19′58″W / 37.23500°N 77.33278°W |

| Type | U.S. Army post |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | U.S. Army |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1917 |

| In use | 1917–1924 1941–present |

| Garrison information | |

| Garrison | Combined Arms Support Command (CASCOM)/Sustainment Center of Excellence (SCoE) U.S. Army Quartermaster School U.S. Army Ordnance School U.S. Army Transportation School Army Sustainment University (ALU) Defense Commissary Agency (DeCA) |

Fort Gregg-Adams, in Prince George County, Virginia, United States, is a United States Army post and headquarters of the United States Army Combined Arms Support Command (CASCOM)/ Sustainment Center of Excellence (SCoE), the U.S. Army Quartermaster School, the U.S. Army Ordnance School, the U.S. Army Transportation School, the Army Sustainment University (ALU), Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA), and the U.S. Defense Commissary Agency (DeCA).

Fort Gregg-Adams also hosts two Army museums, the U.S. Army Quartermaster Museum and the U.S. Army Women's Museum. The equipment and other materiel associated with the Army's Ordnance Museum was moved to Fort Gregg-Adams in 2009–2010 for use by the United States Army Ordnance Training and Heritage Center.

The installation was initially named Camp Lee (changed to Fort Lee in 1950) after Confederate States General Robert E. Lee.[1] It was one of the U.S. Army installations named for Confederate soldiers that the U.S. Naming Commission had recommended be renamed. On August 8, 2022, the commission proposed the name be changed to Fort Gregg-Adams, after Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg and Lieutenant Colonel Charity Adams Earley.[2] On October 6, 2022, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin accepted the recommendation and directed the name change occur no later than January 1, 2024.[3] On January 5, 2023, William A. LaPlante, US under-secretary of defense for acquisition and sustainment, directed the full implementation of the recommendations.[4] On April 27, 2023, the post was redesignated Fort Gregg-Adams.[5] It is the first U.S. military base to be named for African Americans.

Fort Gregg-Adams is a census-designated place (CDP) with a population of 9,874 as of the 2020 census – nearly triple the size of the 2010 census count.[6]

History

[edit]World War I

[edit]

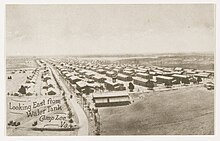

Just 18 days after a state of war with Germany was declared, the first Camp Lee was established as a state mobilization camp and later became a division training camp.[1]

Camp Lee was the mobilization center for the 80th Division, the Blue Ridge Division. Because of significant common heritage in the past (Colonial Wars, Revolutionary War, and Civil War), residents of Pennsylvania, Virginia and West Virginia became the structure of the 80th Division. The 80th Division was organized in August 1917 at Camp Lee, Virginia. The units were made up mostly of men from the above three states.[7]

Before long, Camp Lee became one of the largest "cities" in Virginia. More than 60,000 Doughboys trained here prior to their departure for the Western Front and fighting in France and Germany. Included among the many facilities here was a large camp hospital situated on 58 acres of land. One of the more trying times for the hospital staff was when the worldwide influenza epidemic reached Camp Lee in the fall of 1918. An estimated 10,000 Soldiers were stricken by flu. Nearly 700 of them died during a couple of weeks.[8]

In June 1917, building began and within sixty days some 14,000 men were on the installation. The post was home to the 155th Depot Brigade. The role of depot brigades was to receive recruits and draftees, then organize them and provide them with uniforms, equipment and initial military training. Depot brigades also received soldiers returning home at the end of the war and carried out their mustering out and discharges. When construction work ended, there were accommodations for 60,335 men.

In 1920 Camp Lee was still active, as the US 1920 Census showed many soldiers still stationed there. After World War I, Camp Lee was taken over by the Commonwealth of Virginia and designated a game preserve. Later, portions of the land were incorporated into the Petersburg National Battlefield and the Federal Correctional Institution, Petersburg. In 1921, the camp was formally closed, and its buildings were torn down, all save one – the so-called “White House.” During the war, this two-story wood-framed structure served as 80th Division Headquarters and as temporary residence for its Commander, Major General Adelbert Cronkhite. Years later, it became known as the “Davis House” in honor of the family that lived there in the 1930s and 40s.[8]

World War II

[edit]In October 1940, the War Department ordered the construction of another Camp Lee on the site of the earlier installation. Built as rapidly as the first, construction was still ongoing when the Quartermaster Replacement Training Center (QMRTC) started operation in February 1941. Their number grew to 25,000 in 1942, and peaked at 35,000 in 1944.

While the QMRTC was getting underway, the Quartermaster School was transferred to Camp Lee. In October 1941 (two months before Pearl Harbor), the Quartermaster School moved from Philadelphia to Camp Lee to begin training Officers and Non-Commissioned officers in the art of military supply and service A full program of courses was conducted, including Officer Candidate School. By the end of 1941, Camp Lee was the center of both basic and advanced training of Quartermaster personnel and held this position throughout the war.

Over the course of the war, Camp Lee's population continued to mushroom until it became, in effect, the third largest “city” in Virginia, after Norfolk and Richmond. More than 50,000 officers attended Quartermaster Officer Candidate School. Over 300,000 Quartermaster Soldiers trained here during the war. There was a Regional Hospital with scores of pavilions and literally miles of interlocking corridors capable of housing over 2,000 patients at a time. Here too was located the Army Services Forces Training Center, the Quartermaster (Research & Development) Board, a Women's Army Corps training center, and for a while, a prisoner of war camp and the Medical Replacement Training Center. Camp Lee enjoyed a reputation as one of the most effective and best-run military installations in the country.[8]

Camp Lee was also the home of a Medical Replacement Training Center (MRTC), but as the Quartermaster training increased, it was decided to relocate the MRTC to Camp Pickett. Later, the QMRTC was re-designated as an Army Services Forces Training Center, but it retained its basic mission of training Quartermaster personnel.

Post–World War II era

[edit]1945–1950

[edit]In 1946, the War Department announced that Camp Lee would be retained as the center for quartermaster training in the Army. The Quartermaster School continued operation, and in 1947, the Adjutant General's School moved here and remained until 1951.

The Women's Army Corps likewise established its premier training center here from 1948 to 1954. Also in 1948, the first permanent brick and mortar structure—the Post Theater (Powhatan Beaty Theater)—was constructed.[8]

1950 – 1965: Cold War Era growth

[edit]During the Korean War (1950 -1953), tens of thousands of Soldiers arrived at Fort Lee to receive logistics training before heading overseas. Official recognition of its permanent status was obtained in 1950 and the post was redesignated Fort Lee.

After the Korean War, progress was made on an ambitious permanent building program.

Air Force SAGE site

[edit]In 1956, the Fort Lee Air Force Station on post was selected for a Semi Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) system direction center (DC) site, designated DC-04. The four-story block house was built to house two parallel AN/FSQ-7 Computers that could receive inputs from sensors on the East Coast and provide actionable information on incoming Soviet air threats. [1]

- On 1 December 1956 the 4625th Air Defense Wing (SAGE) was activated.

- On 8 January 1957 the 4625th was redesignated as the newly activated Washington Air Defense Sector at Fort Lee.

- The WaADS was initially assigned to the 85th Air Division but on 1 September 1958 it was transferred to the 26th Air Division.

- In February 1959 the new Semi Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) Direction Center (DC-04) became operational and oversaw Washington Air Defense Sector operations.37°15′09″N 077°19′21″W / 37.25250°N 77.32250°W The day-to-day operations of the command were to train and maintain tactical units flying jet interceptor aircraft (F-101 Voodoo; F-102 Delta Dagger; F-106 Delta Dart) or interceptor missiles (CIM-10 Bomarc) in a state of readiness with training missions and series of exercises with Strategic Air Command and other units simulating interceptions of incoming Soviet aircraft.

First permanent structures built

[edit]The 1950s and 1960s witnessed almost nonstop modernization efforts as, one-by-one, Fort Lee's temporary wooden barracks, training facilities and housing units began giving way to permanent brick and cinderblock structures. New multi-storied barracks were built in the mid-50s, along with whole communities of Capehart housing for permanent party. In May 1961, the new three-story Quartermaster School, Mifflin Hall, was dedicated. Kenner Army Hospital opened in 1962, replacing the remnants of the old WWII-era facility, and the privately funded Quartermaster Museum opened its doors in 1963. Some years have seen far more change than others, but the overall process of modernization has continued ever since.[8]

Locus for Quartermaster Training

[edit]The Quartermaster Training Center, created to supervise the training of Quartermaster personnel and troop units, brought an intensification of training activity within the Quartermaster Corps. As a result, the courses formerly taught at other locations were incorporated in the curriculum of the Quartermaster School.

Profound changes were evident at Fort Lee during 1962. The post became a Class 1 military installation under Second United States Army. The Quartermaster School became a part of the Continental Army Command service school system and was also selected to serve as the home of the Quartermaster Corps. The Second United States Army was inactivated at Fort Lee in 1966 until its reactivation at Fort Gillem, Georgia in 1983.

1965 – 1990 Vietnam and Post-Vietnam: Consolidation of Logistics under TRADOC

[edit]

The rapid logistics buildup in Vietnam after 1965 signaled an urgent need for many more Quartermaster Soldiers. Fort Lee responded by going into overdrive. For a time, the school maintained three shifts, and round-the-clock training. A Quartermaster Officer Candidate School opened in 1966 for the first time since World War II. A mock Vietnamese “village” was created on post to familiarize trainees with guerrilla tactics and the conditions in which they could expect to fight in the jungles of Southeast Asia. Part of the sixties-era Quartermaster training program also saw the first widespread local use of automated data processing equipment.[8]

In July 1973, Fort Lee came under the control of U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command.[9] Additionally, the U.S. Army Logistics Center was established in 1973 to serve as an “integrating center” for the Quartermaster, Transportation, Ordnance, and Missile and Munitions Centers and Schools – the traditional Combat Service Support branches.

Again in 1990, there was a post reorganization and restructuring and the U.S. Army Logistics Center was re-designated the U.S. Army Combined Arms Support Command (CASCOM), and the CASCOM Commander became the Fort Lee Installation Commander as well.

2000s – 2020: 9/11, BRAC, and Sustainment Center of Excellence

[edit]In May 2001, the U.S. Army Women's Museum (AWM) relocated to Fort Lee. It offered more than 13,000 sq. feet of gallery space and thousands of artifacts used to tell the long, proud history of women in the Army. Additionally, the installation hosted a growing number of tenant activities such as the Army Logistics Management Center (ALMC), Readiness Group Lee, Materiel Systems Analysis Activity, the General Leonard T. Gerow U.S. Army Reserve Center, the Defense Commissary Agency (DECA), USAR 80th Division, and several other Department of Army and Department of Defense activities.[8]

Base Realignment and Closure 2005

[edit]

In 2005, the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) law was passed by Congress. One of BRAC's requirements was the relocation of the United States Army Ordnance Corps headquarters, the United States Army Ordnance Munitions and Electronic Maintenance School (OMMS) from Aberdeen Proving Ground, the United States Army Ordnance Munitions and Electronic Maintenance School (OMEMS) from Redstone Arsenal, Alabama, and the Ordnance Museum to Fort Gregg-Adams by September 2011.[10] The transfer of artifacts from Aberdeen to Fort Gregg-Adams began in August 2009, with the former museum now designated the U.S. Army Ordnance Training and Heritage Center at Fort Gregg-Adams.[10] Also, the headquarters of the U.S. Army Transportation Center and School from Fort Eustis was brought to the installation.

One of the principal parts of BRAC was the Sustainment Center of Excellence (SCoE) headquarters building project. In the summer of 2007, there was a ground-breaking ceremony on Sergeant Seay Field, the site of the new facility. The SCoE headquarters took 18 months to build and was formally dedicated in January 2009. It now houses the Combined Arms Support Command and command groups for the Quartermaster, Ordnance, and Transportation Corps. During a ceremony on July 30, 2010, the old CASCOM headquarters was officially retired, and the new building was proudly rededicated as “Mifflin Hall.” To help make way for the structure, the First Logistical Command Memorial – which had been located on that site since 1974 – was carefully unmoored and moved to a more prominent spot facing the main post entrance.[8]

In addition, a new U.S. Army Logistics University was built and opened in July 2009 to centralize basic and advanced NCO, warrant officer, commissioned officer and government civilian leadership training for all Army sustainment branches. The 400,000-square-foot building now offers more than 200 courses and trains upward of 2,300 military and civilian students daily. Its International Studies program is attended by military personnel from more than 30 allied countries.[11]

Fort Gregg-Adams is the country's first army post to host a 'full-size' statue commemorating the service of women in the Army. The statue was unveiled in 2013.[12]

The installation emerged as the center of logistics and sustainment for the U.S. Army. With the completion of the BRAC construction projects, the installation acquired 6.5 million square feet of new facilities and about 70,000 troops now train here each year. In 2017, the post marked its Centennial with a year-long celebration themed "A Century of Support to the Nation."

2020s: Operation Allies Refuge and name change from Fort Lee to Fort Gregg-Adams

[edit]In July 2021, the post was tasked to support Operation Allies Refuge, with a goal of helping Afghan evacuees transition to a new life in the United States at the conclusion of the war in Afghanistan. Post leaders assembled a group called “Task Force Eagle,” which spent the next four months supporting OAR. The Department of Defense, through U.S. Northern Command, and in support of the Department of State and Department of Homeland Security, provided transportation, temporary housing, medical screening and general support for Afghan evacuees at military facilities across the country.[8]

The mission was to support vulnerable Afghans and their families while they finished processing with immigration services, applied for work authorizations and underwent medical care prior to resettlement in the U.S. Fort Gregg-Adams (then Fort Lee) was the first of eight installations selected to provide temporary lodging and other living needs for the Afghan evacuees. The post was initially identified by the U.S. Army as an east coast location that could quickly be used to provide temporary housing for Afghans and their families to finish administrative checks and undergo the necessary medical exams to qualify for a Special Immigrant Visa. Over 3,000 of them were temporarily housed on post by the end of November 2021 when the mission was concluded.

Renamed to Fort Gregg-Adams

[edit]

On 27 April 2023 during a redesignation ceremony[13] the name of Fort Lee was changed to Fort Gregg-Adams which is named after two African American officers Lt. Gen. Arthur J. Gregg and Lt. Col. Charity Adams.[5][2] The name change was recommended by the Commission on the Naming of Items of the Department of Defense[14] as part of the renaming of military assets which were associated with the Confederate States of America.[15][16] The naming of Fort Gregg-Adams is notable as it is the first time since 1900 where a fort has been named after a service member who is still alive.[2] It is also the first named for African Americans.[17]

Other infrastructure on the base had been renamed including the street signs along the former Lee Avenue, now Gregg Avenue, and the signage for the Gregg-Adams Officers' Club on base, into which notably Lt. Gen. Arthur Gregg had been denied entrance back in 1950 as a young Second Lieutenant, at a time when discrimination and segregation were still being practiced against African American Uniformed Personnel, even against an executive order to the contrary, signed by President Harry S. Truman two years prior.[18][19][20]

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 8.4 square miles (21.6 km2), all of it land.

Demographics

[edit]Fort Gregg-Adams, Virginia | |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| State | Virginia |

| Counties | Prince George |

| Elevation | 98 ft (30 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 9,874 |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| GNIS feature ID | 1492869[21] |

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 12,435 | — | |

| 1980 | 9,784 | −21.3% | |

| 1990 | 6,895 | −29.5% | |

| 2000 | 7,269 | 5.4% | |

| 2010 | 3,393 | −53.3% | |

| 2020 | 9,874 | 191.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[22] | |||

As of the census[23] of 2000, there were 7,269 people, 1,401 households, and 1,223 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 870.2 people per square mile (336.1/km2). There were 1,445 housing units at an average density of 173.0/sq mi (66.8/km2). The racial makeup of the CDP was 47.1% African American, 39.5% White, 0.7% Native American, 2.3% Asian, 0.4% Pacific Islander, 6.7% from other races, and 3.4% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 11.4% of the population.

There were 1,401 households, out of which 72.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 70.0% were married couples living together, 14.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 12.7% were non-families. 11.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 0.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.27 and the average family size was 3.53.

In the CDP the population was spread out, with 27.9% under the age of 18, 34.0% from 18 to 24, 35.8% from 25 to 44, 2.1% from 45 to 64, and 0.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 22 years. For every 100 females there were 132.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 143.3 males.

The median income for a household in the CDP was $36,325, and the median income for a family was $40,197. Males had a median income of $27,511 versus $19,459 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $12,448. About 6.3% of families and 7.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 8.8% of those under age 18 and none of those age 65 or over.

Current units

[edit]- Kenner Army Health Clinic

- 54th Quartermaster Battalion

- 111th Quartermaster Battalion

- 94th Training Division

- 345th Training Squadron (USAF)

- 262 Quartermaster Battalion

- 266 Quartermaster Battalion

Climate

[edit]The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Fort Gregg-Adams has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[24]

Education

[edit]All areas in Prince George County,[25] including on-post housing at Fort Gregg-Adams, are within Prince George County Public Schools. The Department of Defense Education Activity (DoDEA) does not operate any schools on post at Fort Gregg-Adams.[26] The comprehensive high school of the county is Prince George High School.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Naming of U.S. Army Posts". U.S. Army Center of Military History. 7 September 2023.

- ^ a b c Neuman, Scott (27 April 2023). "An Army fort named after Robert E. Lee now honors 2 pioneering Black officers". National Public Radio.

Lt. Gen. Arthur Gregg, the first African American to achieve such a high rank, retired in 1981 after serving as the Army's deputy chief of staff, logistics. He becomes the only living soldier in modern history to have an installation named in his honor. Lt. Col. Charity Adams joined the newly created Women's Army Auxiliary Corps in 1942 and was the highest-ranking Black woman of World War II.

- ^ Lloyd Austin (6 October 2022). "Memorandum for Senior Pentagon Leadership, Defense Agency and DoD Field Activity Directors: Subject: Implementation of the Naming Commission's Recommendations" (PDF). Secretary of Defense. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ Pat Ryder. (5 January 2023) Transcript: Pentagon Press Secretary Air Force Brig. Gen. Pat Ryder Holds an On-Camera Press Briefing. U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ a b Baker, Stephen (23 March 2023). "Fort Lee to be redesignated as Fort Gregg-Adams". US Army. Fort Lee Public Affairs. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

Fort Lee will become Fort Gregg-Adams during a redesignation ceremony April 27, honoring two Black officers who excelled in the field of sustainment and made significant marks in U.S. Army history.

- ^ "Census Quick Facts for Fort Gregg-Adams, VA". Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ Stultz, Russell (2004). Anthony, Lee S. (ed.). History of the Eightieth Division A.E.F. in World War I: The Blue Ridge Division. Published by The Descendants of the 80th Division Veterans. ISBN 0-9759341-7-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Fort Gregg-Adams History". Fort Gregg-Adams Command History Webpage. Command History Office, US Army. 11 September 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Fort Lee statue honors female warriors". Tri-Cities News. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 8 November 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Ordnance tanks, artillery arrive at Fort Lee". Fort Lee Public Affairs Office. 5 August 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ^ Command History Office (11 September 2023). "Army Sustainment University History". Army Sustainment University Command History Webpage.

- ^ Bell, T. Anthony (13 November 2013). "'Lt. FAWMA' -- Army Women's Museum unveils one-of-kind statue of female Soldier". www.army.mil. US Army. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Brown, Stacy (25 April 2023). "Army Removing Confederate Name of Virginia Fort to Honor Black Heroes". The Atlanta Voice. Atlanta, Georgia. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

A redesignation ceremony is planned for Thursday, April 27, honoring the two Black officers whom officials said excelled in the field of sustainment and made significant marks in U.S. Army history.

- ^ Horton, Alex; Demirjian, Karoun (24 May 2022). "Bases named for Confederates should honor women, minorities instead, panel says". Washington Post. Washington, District of Columbia. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

The panel established by Congress to identify new names for nine Army installations honoring Confederate military officers presented its recommendations Tuesday, bringing the Defense Department one step closer to stripping the rebel monikers from some of its most prominent bases.

- ^ Garamone, Jim (5 January 2023). "DOD Begins Implementing Naming Commission Recommendations". U.S. Department of Defense. Department of Defense News. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

Retired Navy Adm. Michelle Howard chaired the congressionally mandated Naming Commission. The commission's mission was to provide removal and renaming recommendations for all DOD items "that commemorate the Confederate States of America or any person who served voluntarily with the Confederate States of America."

- ^ Watson, Eleanor (5 January 2023). "Military to proceed with changing the names of bases honoring Confederate generals". CBS News. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

Renaming ceremonies for the nine bases named after Confederate generals will take place over the course of the year, officials say, but work to take down Confederate iconography elsewhere has already begun.

- ^ Davidson, Joe (18 August 2023). "Perspective | Army base, once named for an enslaver, now honors slavery descendants". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

- ^ Bell, Terrance (21 April 2023). "Club renamed for Black Army officer previously denied entrance". US Army. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

During a short, informal ceremony April 19, retired Lt. Gen. Gregg helped to unveil the revamped marquee that now welcomes visitors to the Gregg-Adams Club

- ^ Neuman, Scott (27 April 2023). "An Army fort named after Robert E. Lee will now honor 2 pioneering Black officers". NPR. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Bell, Terrance (26 April 2023). "Garrison professionals are key part of momentous Gregg-Adams redesignation". DVIDS. Richmond, Virginia: US Department of Defense. Defense Visual Information Distribution Service. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Bell, Terrance (26 April 2023). "Garrison professionals are key part of momentous Gregg-Adams redesignation". DVIDS. Richmond, Virginia: US Department of Defense. Defense Visual Information Distribution Service. Retrieved 27 April 2023. The most visible "prominent" elements recently updated include the street signs along the former Lee Avenue – now Gregg Avenue – leading motorists to Gregg-Adams Club lawn expanse. They were changed a week ago. Other items addressed around the same time included water towers, signage at the recently redesignated Gregg-Adams Club, and the main installation sign along Route 36 – shrouded at the time of this article but set for unveiling once the post is officially redesignated.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Fort Gregg-Adams

- ^ "Decennial Census by Decade". US Census Bureau.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- ^ "Fort Lee, Virginia: Köppen Climate Classification". Weatherbase.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Prince George County, VA" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 21 December 2024. - Text list

- ^ "Fort Gregg-Adams Education". Militaryonesource. Retrieved 21 December 2024. - .mil website.

External links

[edit]- Fort Gregg-Adams (official site)

- U.S. Army Quartermaster Museum Archived 7 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine (official site)

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Fort Lee

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Army

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Army