Gomoku

| |

| Genres | Board game Abstract strategy game |

|---|---|

| Players | 2 |

| Setup time | Minimal |

| Chance | None |

| Skills | Strategy, tactics |

Gomoku, also called Five in a Row, is an abstract strategy board game. It is traditionally played with Go pieces (black and white stones) on a 15×15 Go board[1][2] while in the past a 19×19 board was standard.[3][4] Because pieces are typically not moved or removed from the board, gomoku may also be played as a paper-and-pencil game. The game is known in several countries under different names.

Rules

[edit]Players alternate turns placing a stone of their color on an empty intersection. Black plays first. The winner is the first player to form an unbroken line of five stones of their color horizontally, vertically, or diagonally. In some rules, this line must be exactly five stones long; six or more stones in a row does not count as a win and is called an overline.[5][6] If the board is completely filled and no one has made a line of 5 stones, then the game ends in a draw.

Origin

[edit]Historical records indicate that the origins of gomoku can be traced back to the mid-1700s during the Edo period. It is said that the 10th generation of Kuwanaya Buemon, a merchant who frequented the Nijō family, was highly skilled in this game, which subsequently spread among the people. By the late Edo period, around 1850, books had been published on gomoku.[7] The earliest published book on gomoku that can be verified is the Gomoku Jōseki Collection (五石定磧集) in 1856.[8]

The name "gomoku" is from the Japanese language, in which it is referred to as gomokunarabe (五目並べ). Go means five, moku is a counter word for pieces and narabe means line-up. The game is popular in China, where it is called Wuziqi (五子棋).[9] Wu (五 wǔ) means five, zi (子 zǐ) means piece, and qi (棋 qí) refers to a board game category in Chinese. The game is also popular in Korea, where it is called omok (오목 [五目]) which has the same structure and origin as the Japanese name.

In the nineteenth century, the game was introduced to Britain where it was known as Go Bang, said to be a corruption of the Japanese word goban, which was itself adapted from the Chinese k'i pan (qí pán) "go-board."[10]

First-player advantage

[edit]Gomoku has a strong advantage for the first player when unrestricted.[11][12]

Championships in gomoku previously used the "Pro" opening rule, which mandated that the first player place the first stone in the center of the board. The second player's stone placement was unrestricted. The first player's second stone had to be placed at least three intersections away from the first player's first stone. This rule was used in the 1989 and 1991 world championships.[13] When the win–loss ratio of these two championships was calculated, the first player (black) won 67 percent of games.

This was deemed too unbalanced for tournament play, so tournament gomoku adopted the Swap2 opening protocol in 2009. In Swap2, the first player places three stones, two black and one white, on the board. The second player then selects one of three options: play as black, play as white and place another white stone, or place two more stones, one white and one black, and let the first player choose the color.[14][15]

The win ratio of the first player has been calculated to be around 52 percent using the Swap2 opening protocol, greatly balancing the game and largely solving the first-player advantage.[11][12][16]

Variants

[edit]Freestyle gomoku

[edit]Freestyle gomoku has no restrictions on either player and allows a player to win by creating a line of five or more stones, with each player alternating turns placing one stone at a time.

Swap after 1st move

[edit]The rule of "swap after 1st move" is a variant of the freestyle gomoku rule, and is mostly played in China. The game can be played on a 19×19 or 15×15 board. As per the rule, once the first player places a black stone on the board, the second player has the right to swap colors. The rest of the game proceeds as freestyle gomoku. This rule is set to balance the advantage of black in a simple way.[17]

Black (the player who makes the first move) has long been known to have an advantage, even before L. Victor Allis proved that black can force a win (see below). Renju attempts to mitigate this imbalance with extra rules that aim to reduce black's first player advantage.

It is played on a 15×15 board, with the rules of three and three, four and four, and overlines applied to Black only.[6]

- The rule of three and three bans a move that simultaneously forms two open rows of three stones (rows not blocked by an opponent's stone at either end).

- The rule of four and four bans a move that simultaneously forms two rows of four stones (open or not).

- Overlines prevent a player from winning if they form a line of 6 or more stones.[6][18]

Renju also makes use of various tournament opening rules, such as Soosõrv-8, the current international standard.[19]

Caro

[edit]In Caro, (also called gomoku+, popular among Vietnamese), the winner must have an overline or an unbroken row of five stones that is not blocked at either end (overlines are immune to this rule). This makes the game more balanced and provides more power for White to defend.[20]

Omok

[edit]Omok is similar to Freestyle gomoku; however, it is played on a 19×19 board and includes the rule of three and three.[21][22]

Ninuki-renju

[edit]Also called Wu, Ninuki Renju is a variant which adds capturing to the game; A pair of stones of the same color may be captured by the opponent by means of custodial capture (sandwiching a line of two stones lengthwise). The winner is the player either to make a perfect five in a row, or to capture five pairs of the opponent's stones. It uses a 15x15 board and the rules of three and three and overlines. It also allows the game to continue after a player has formed a row of five stones if their opponent can capture a pair across the line.[23]

Pente is related to Ninuki-Renju, and has the same custodial capture method, but is most often played on a 19x19 board and does not use the rules of three and three, four and four, or overlines.[24]

Tournament Opening Rules

[edit]Tournament rules are used in professional play to balance the game and mitigate the first player advantage. The tournament rule used for the gomoku world championships since 2009 is the Swap2 opening rule. For all of the following professional rules, an overline (six or more stones in a row) does not count as a win.[16]

Pro

[edit]The first player's first stone must be placed in the center of the board. The second player's first stone may be placed anywhere on the board. The first player's second stone must be placed at least three intersections away from the first stone (two empty intersections in between the two stones).[15]

Long Pro

[edit]The first player's first stone must be placed in the center of the board. The second player's first stone may be placed anywhere on the board. The first player's second stone must be placed at least four intersections away from the first stone (three empty intersections in between the two stones).[15][25]

Swap

[edit]The tentative first player places three stones (two black, and one white) anywhere on the board. The tentative second player then chooses which color to play as. Play proceeds from there as normal with white playing their second stone.[15]

Swap2

[edit]The tentative first player places three stones on the board, two black and one white. The tentative second player then has three options:

- They can choose to play as white and place a second white stone

- They can swap their color and choose to play as black

- Or they can place two more stones, one black and one white, and pass the choice of which color to play back to the tentative first player.

Because the tentative first player doesn't know where the tentative second player will place the additional stones if they take option 3, the swap2 opening protocol limits excessive studying of a line by only one of the players.[14][15]

Theoretical generalizations

[edit]m,n,k-games are a generalization of gomoku to a board with m×n intersections, and k in a row needed to win. Connect Four is (7,6,4) with piece placement restricted to the lowest unoccupied place in a column.

Connect(m,n,k,p,q) games are another generalization of gomoku to a board with m×n intersections, k in a row needed to win, p stones for each player to place, and q stones for the first player to place for the first move only. In particular, Connect(m,n,6,2,1) is called Connect6.

Example game

[edit]

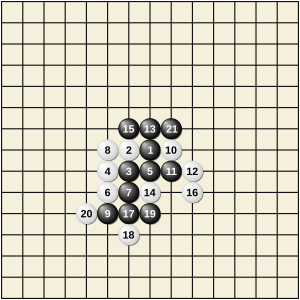

This game on the 15×15 board is adapted from the paper "Go-Moku and Threat-Space Search".[26]

The opening moves show clearly black's advantage. An open row of three (one that is not blocked by an opponent's stone at either end) has to be blocked immediately, or countered with a threat elsewhere on the board. If not blocked or countered, the open row of three will be extended to an open row of four, which threatens to win in two ways.

White has to block open rows of three at moves 10, 14, 16 and 20, but black only has to do so at move 9. Move 20 is a blunder for white (it should have been played next to black 19). Black can now force a win against any defense by white, starting with move 21.

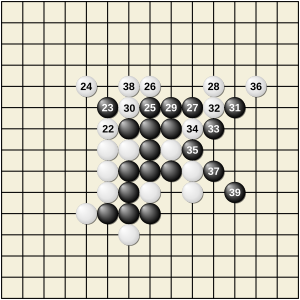

There are two forcing sequences for black, depending on whether white 22 is played next to black 15 or black 21. The diagram on the right shows the first sequence. All the moves for white are forced. Such long forcing sequences are typical in gomoku, and expert players can read out forcing sequences of 20 to 40 moves rapidly and accurately.

The diagram on the right shows the second forcing sequence. This diagram shows why white 20 was a blunder; if it had been next to black 19 (at the position of move 32 in this diagram) then black 31 would not be a threat and so the forcing sequence would fail.

World championships

[edit]World Gomoku Championships have occurred 2 times in 1989, 1991.[13] Since 2009 tournament play has resumed, with the opening rule changed to swap2.[16]

List of the tournaments occurred and title holders follows.

| Title year | Hosting city, country | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Opening rule |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | Pro | ||||

| 1991 | Pro | ||||

| 2009 | Swap2 | ||||

| 2011 | Swap2 | ||||

| 2013 | Swap2 | ||||

| 2015 | Swap2 | ||||

| 2017 | Swap2 | ||||

| 2019 | Swap2 | ||||

| 2023 | Swap2 |

| Title year | Hosting city, country | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Opening rule | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Michał Żukowski Michał Zajk Łukasz Majksner Piotr Małowiejski |

Pavel Laube Igor Eged Štěpán Tesařík Marek Hanzl |

Lu Wei-Yuan Chen Ko-Han Chang Yi-Feng Sung Pei-Jung |

Swap2 | ||||||

| 2018 | Edvard Rizvanov Denis Osipov Ilya Muratov Maksim Karasev Mikhail Kozhin |

Zoltán László Gergő Tóth Márk Horváth Gábor Gyenes Attila Hegedűs |

Łukasz Majksner Michał Żukowski Michał Zajk Marek Gorzecki Paweł Tarasiński |

Swap2 | ||||||

| 2020 |

| |||||||||

Computers and gomoku

[edit]Researchers have been applying artificial intelligence techniques on playing gomoku for several decades. Joseph Weizenbaum published a short paper in Datamation in 1962 entitled "How to Make a Computer Appear Intelligent"[27] that described the strategy used in a gomoku program that could beat novice players. In 1994, L. Victor Allis raised the algorithm of proof-number search (pn-search) and dependency-based search (db-search), and proved that when starting from an empty 15×15 board, the first player has a winning strategy using these searching algorithms.[28] This applies to both free-style gomoku and standard gomoku without any opening rules. It seems very likely that black wins on larger boards too. In any size of a board, freestyle gomoku is an m,n,k-game, hence it is known that the first player can force a win or a draw. In 2001, Allis's winning strategy was also approved for renju, a variation of gomoku, when there was no limitation on the opening stage.[29]

However, neither the theoretical values of all legal positions, nor the opening rules such as Swap2 used by the professional gomoku players have been solved yet, so the topic of gomoku artificial intelligence is still a challenge for computer scientists, such as the problem on how to improve the gomoku algorithms to make them more strategic and competitive. Nowadays[when?], most of the state-of-the-art gomoku algorithms are based on the alpha-beta pruning framework.[citation needed]

Reisch proved that Generalized gomoku is PSPACE-complete.[30] He also observed that the reduction can be adapted to the rules of k-in-a-Row for fixed k. Although he did not specify exactly which values of k are allowed, the reduction would appear to generalize to any k ≥ 5.[31]

There exist several well-known tournaments for gomoku programs since 1989. The Computer Olympiad started with the gomoku game in 1989, but gomoku has not been in the list since 1993.[32] The Renju World Computer Championship was started in 1991, and held for 4 times until 2004.[33][34] The Gomocup tournament is played since 2000 and taking place every year, still active now[when?], with more than 30 participants from about 10 countries.[35] The Hungarian Computer Go-Moku Tournament was also played twice in 2005.[36][37] There were also two Computer vs. Human tournaments played in the Czech Republic, in 2006 and 2011.[38][39] Not until 2017 were the computer programs proved to be able to outperform the world human champion in public competitions. In the Gomoku World Championship 2017, there was a match between the world champion program Yixin and the world champion human player Rudolf Dupszki. Yixin won the match with a score of 2–0.[40][41]

In popular culture

[edit]Gomoku was featured in a 2018 Korean drama by Baek Seung-Hwa starring Park Se-wan. The film follows Baduk Lee (Park Se-wan), a former go prodigy who retired after a humiliating loss on time. Years later, Baduk Lee works part time at a go club, where she meets Ahn Kyung Kim, who introduces her to an Omok (Korean gomoku) tournament. Lee is initially uninterested and considers Omok a children's game, but after her roommate loses money on an impulse purchase, she enters the tournament for the prize money and loses badly, being humiliated once again. Afterwards, she begins training to redeem herself and becomes a serious omok player.[42]

In the video game Vintage Story omok boards and pieces (made of gold and lead) can occasionally be found in ruins or as part of luxury traders' inventory. The board and pieces are functional, allowing players to have actual omok matches. In-universe, omok is so far the only game surviving from the times before the Rot.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Gomoku - Japanese Board Game". Japan 101. Archived from the original on 2014-03-26. Retrieved 2013-06-25.

- ^ "Game Theory | GomokuWorld.com". gomokuworld.com. Archived from the original on 2021-07-22. Retrieved 2021-07-28.

- ^ Lasker, Edward (1960). Go and go-moku: the oriental board games (2nd rev. ed.). New York: Dover. ISBN 9780486206134.

- ^ "The rules and the history of Renju and other five-in-a-row games." Luffarschack, renju.se/rif/r1rulhis.htm. Accessed 28 July 2021.

- ^ "Game Theory | GomokuWorld.com". gomokuworld.com. Archived from the original on 2021-07-22. Retrieved 2021-07-22.

- ^ a b c "The Renju International Federation portal - RenjuNet". www.renju.net. Archived from the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2023-02-10.

- ^ "About the origin and rules of renju". Nihon Renju-sha (in Japanese). 2022-09-19. Archived from the original on 2023-04-03. Retrieved 2023-04-26.

- ^ "Origins of renju". www.success-simulation.com. 1999-10-01. Archived from the original on 2022-03-31. Retrieved 2023-04-26.

- ^ "The Renju International Federation portal - RenjuNet". www.renju.net. Retrieved 2023-04-30.

- '^ OED citations: 1886 GUILLEMARD Cruise 'Marchesa I. 267 Some of the games are purely Japanese..as go-ban. Note, This game is the one lately introduced into England under the misspelt name of Go Bang. 1888 Pall Mall Gazette 1. Nov. 3/1 These young persons...played go-bang and cat's cradle. The board below shows the three types of winning arrangements as they might appear on an 8x8 Petteia board. Obviously the cramped conditions would result in a draw most of the time, depending on the rules. Play would be easier on a larger Latrunculi board of 12x8 or even 10x11. .

- ^ a b "BoardGameGeek". boardgamegeek.com. Archived from the original on 2021-07-22. Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- ^ a b "Game database | GomokuWorld.com". gomokuworld.com. Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- ^ a b "The Renju International Federation portal - RenjuNet". Renju.net. Archived from the original on 2021-07-22. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- ^ a b "Gomoku - swap2 rule". renju.net. Retrieved 2016-11-09.

- ^ a b c d e "Opening rules | GomokuWorld.com". gomokuworld.com. Archived from the original on 2021-07-22. Retrieved 2021-07-07.

- ^ a b c "History | GomokuWorld.com". gomokuworld.com. Archived from the original on 2021-07-07. Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- ^ "Swap after 1st move rule". www.wuzi8.com (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2021-12-08. Retrieved 2023-04-28.

- ^ "The Renju International Federation portal - RenjuNet". Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-22.

- ^ "The Renju International Federation portal - RenjuNet". renju.net. Archived from the original on 2021-07-22. Retrieved 2021-07-22.

- ^ "Caro (aka Gomoku)". LearnPlayWin. Archived from the original on 2021-07-22. Retrieved 2021-07-22.

- ^ "Omok: A Korean Game of Five Stones". KPOP Jacket Lady. 2016-10-06. Archived from the original on 2021-07-22. Retrieved 2021-07-22.

- ^ Sungjin, Nam. "Omok." Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture, National Folk Museum of Korea, https://web.archive.org/web/20210722180119/https://folkency.nfm.go.kr/en/topic/detail/1587 . Accessed 22 July 2021.

- ^ "Rules of Pente, Keryo-Pente and Ninuki". Renju. Archived from the original on 2021-07-22. Retrieved 2021-07-22.

- ^ "Pente". www.mindsports.nl. Archived from the original on 2021-07-01. Retrieved 2021-07-22.

- ^ "Gomoku - pro rule". www.renju.net. Retrieved 2021-07-28.

- ^ Allis, L. V., Herik, H. J., & Huntjens, M. P. H. (1993). Go-moku and threat-space search. University of Limburg, Department of Computer Science.

- ^ How to Make a Computer Appear Intelligent, Datamation, February, 1962

- ^ L. Victor Allis (1994). Searching for Solutions in Games and Artificial Intelligence. Ph.D. thesis, University of Limburg, The Netherlands. pp. 121–154. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.99.5364. ISBN 90-900748-8-0.

- ^ J. Wágner and I. Virág (Mar 2001). "Solving Renju". ICGA Journal. 24 (1): 30–35. doi:10.3233/ICG-2001-24104. S2CID 207577292.

- ^ Stefan Reisch (1980). "Gobang ist PSPACE-vollständig (Gomoku is PSPACE-complete)". Acta Informatica. 13: 59–66. doi:10.1007/bf00288536. S2CID 21455572.

- ^ Demaine, Erik; Hearn, Robert (2001). "Playing Games with Algorithms: Algorithmic Combinatorial Game Theory". arXiv:cs/0106019v2.

- ^ "Go-Moku (ICGA Tournaments)". game-ai-forum.org. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ^ "Renju Computer World Championship". 5stone.net. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ^ "4-th World Championship among Computer programs". Nosovsky Japanese Games Home Page. Retrieved 2016-06-03.

- ^ "Gomocup - The Gomoku AI Tournament". Gomocup. Archived from the original on 2016-06-04. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ^ "Hungarian Computer Gomoku Tournament 2005 | GomokuWorld.com". gomokuworld.com. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ^ "2nd Hungarian Computer Go-Moku Open Tournament". sze.hu. Retrieved 2016-06-03.

- ^ "The 1st tournament AI vs. Human (November the 11th, 2006) | Gomocup". gomocup.org. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ^ "AI vs. Člověk 2011 | Česká federace piškvorek a renju". piskvorky.cz. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ^ "Rudolf Dupszki versus Yixin". AIEXP.

- ^ "Rudolf Dupszki vs. Yixin 2017". Facebook.

- ^ Seung-hwa, Baek, writer. Omok Girl. Performance by Park Se-wan, SK Telecom, 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Five-in-a-Row (Renju) For Beginners to Advanced Players ISBN 4-87187-301-3