Farthest South

Farthest South (sometimes stated as Furthest South), describes the most southerly latitude achieved by man before the conquest of the South Pole rendered the term obsolete. In the years before reaching the Pole was a realistic ambition, the achievement of a farthest south record was a matter of considerable pride, particularly on the later British Antarctic expeditions.[1] After Captain Cook crossed the Antarctic Circle in 1773 the record remained in British hands except for a very brief time at the turn of the century (19th to 20th century).[2]

During the Age of Discovery in the 15th and 16th centuries, the main geographical features of the earth's surface were discovered and broadly mapped. Thereafter, explorers were increasingly drawn to the less accessible parts of the earth. A factor which drove adventurers such as Sir Francis Drake was a belief that a great continent lay in the hidden south, a Terra Australis Incognita, or "unknown southern land", envisaged as a fertile El Dorado.[3] Belief in this land, if not in its benign character, persisted into the 18th century and beyond, despite the lack of any hard evidence of its existence. The difficulties and dangers of travelling in the stormy seas south of 50° latitude meant that nothing was discovered of it, apart from a few isolated islands, until the dawn of the modern era when steam started to replace sail. Even then the hostile environment ensured that record southerly latitudes, once established, usually endured for many years.[4] From Ferdinand Magellan's discovery of the Magellan Strait in 1520 there are just eight Farthest South records verified with certainty, until Amundsen closed the matter with his 1911 polar conquest.

Early voyagers

Ferdinand Magellan

Ferdinand Magellan left Seville on 10 August 1519 with a squadron of five ships, in quest of a western route to the Spice Islands[5] (otherwise East Indies). His success depended on his finding a strait or passage through the American land masses. The South American coast was sighted on 6 December, and Magellan moved cautiously southward, following the coast and reaching latitude 49° on 31 March 1520. Little if anything was known of the coast south of this point, and Magellan decided to wait out the southern winter here, establishing the settlement of Puerto San Julian[5]

During the winter Magellan had to suppress a mutiny by two of his captains.[5] In September the journey continued down the uncharted coast, reaching 52°S on 21 October. Here Magellan found a deep inlet which, on investigation, proved to be the strait, later to be known by his name, that he was seeking.[5] As the squadron sailed through it towards the Pacific Ocean they passed through the strait's most southerly point, latitude 54°S, thus establishing the first recorded Farthest South early in November 1520.

However, the principal land south and east of the Magellan Strait is Tierra del Fuego, which was certainly inhabited when Magellan made his passage, making it then the world's most southerly human settlement.[6] It is possible that this local population might from time to time have ventured further southward in boats, perhaps into the waters south of Cape Horn, thereby unconsciously establishing farthest south latitudes well beyond Magellan's mark. None of this, however, is verifiable.

Francisco de Hoces

The first possible sighting of an ocean passage to the Pacific south of Tierra del Fuego is sometimes attributed to Francisco de Hoces of the Loaisa Expedition. In January 1526 his ship San Lesmes was blown south from the Atlantic entrance of the Magellan Strait to a claimed latitude of about 56°S. Hoces reportedly saw a headland, and water beyond it which he did not explore, returning to the Magellan Strait to pass through westward. It is possible, but by no means certain, that in his impromptu journey south he observed Cape Horn and Drake's Passage, more than 50 years before Drake.[7] His claims as to latitude are generally accepted in the Spanish-speaking world.

Sir Francis Drake

During Sir Francis Drake's circumnavigation voyage, 1577–80, with a fleet of five ships under his flagship Pelican (later renamed Golden Hind), he suffered an experience similar to that of Hoces. In September 1578, having passed smoothly through the Magellan Strait into the Pacific, a sudden storm blew his ships far to the south. By this chance he discovered the probability of a strait of water – Drake's Passage – between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. His exact most southerly latitude is not recorded, but it was probably well south of the southernmost extremity of land, Cape Horn, at 56°S. [8]

Garcia de Nodal expedition

The first navigation of Drake's Passage was achieved by the brothers Bartolome and Gonzalo Garcia de Nodal, with the Garcia de Nodal expedition in 1619. In February 1619 the expedition discovered a small group of islands about 60 miles (100 km) SW of Cape Horn, at latitude 56°30’S. They named these the Diego Ramirez Islands after their pilot, Diego Ramirez, the islands remaining the most southerly confirmed land on earth, until Captain Cook's discovery of the South Sandwich Islands in 1775. [9] It is not certain whether the de Nordal expedition then explored south of the Diego Ramirez Islands or whether it passed the southernmost point reached by Drake in 1578.

Early Antarctic explorers

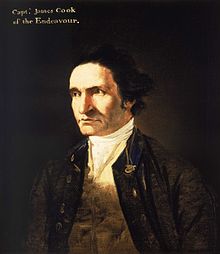

Captain James Cook

Captain Cook's second great voyage, 1772–1775, was primarily a search for the elusive Terra Australis Incognita that was still believed to lie somewhere in the unexplored latitudes below 40°S. [10] His expedition in HMS Resolution and HMS Adventure, which left England in September 1772, would also undertake important scientific work. The two ships sailed from Table Bay, South Africa, on 22 November,[11] heading directly southward. Ice was encountered on 10 December, which became a solid barrier of pack that required great seamanship to circumvent. Breaking through, Cook continued south in open water, and on 17 January 1773 reached the Antarctic Circle at 66°20’S,[12] the first ships to do so. Further progress was barred by ice, and the ships turned north-eastwards, making for New Zealand which they reached on 26 March.[12]

During the ensuing months the expedition explored the southern Pacific Ocean before Cook took Resolution south again – Adventure had retired back to South Africa after a fracas with the New Zealand native population. [13] This time Cook was able to penetrate deep beyond the Antarctic Circle, and on 30 January 1774 had reached 71°10’S, his Farthest South,[14] the state of the ice rendering further southward travel impossible. This southern record would hold for 49 years.

James Weddell

James Weddell was an Anglo-Scottish merchant seaman who undertook several voyages to southern waters, his chief interest being in whaling and sealing rather than scientific or geographical discovery. However, for his third voyage in 1822–24 he had instructions from his employers to "investigate beyond the track of former navigators"[15] and equipped his vessel accordingly. He travelled down the 40°W meridian, deep into the sea that now bears his name, and on 20 February 1823, his ship Jane (160 tons) reached a new Farthest South of 74°15’S, three degrees beyond Cook's former record.[15] Had Weddell continued for another two days' sailing he would have reached the ice shelf eventually discovered in 1912 by Wilhelm Filchner.[15]

James Clark Ross

James Clark Ross's 1839–43 expedition in HMS Erebus and HMS Terror was a full-scale Royal Naval enterprise whose principal function was to test current theories on magnetism and to try and locate the south magnetic pole.[16] Sailing due south from Tasmania in November 1840, the Antarctic Circle was crossed on 1 January 1841. On 11 January land was sighted, a long coastline stretching to the south. Ross called this Victoria Land and followed the coast southwards, passing Weddell's Farthest South on 23 January,[17] and continuing until stopped by the impassable bulk of the Great Ice Barrier. During 300 miles (500 km) of exploration along the edge of this barrier, Ross achieved a latitude of 78°S. [18]. In the following season, returning to the Barrier after wintering in Tasmania, Ross found an inlet which enabled him, on 23 January 1842, to extend his Farthest South to 78°10’S.[19] This record would remain unchallenged for 58 years.

Explorers of the Heroic Age

Carsten Borchgrevink

The Norwegian-born Carsten Egeberg Borchgrevink was a lecturer and explorer who, during 1898–1900, led a British-financed expedition[20] to the Ross Sea area, achieving in 1899 the first over-wintering on the Antarctic mainland by any expedition, at Cape Adare. During the following Antarctic summer of 1899–1900 Borchgrevink's party sailed southward to Ross's Great Ice Barrier and landed at the inlet where Ross had set his mark in 1842. A small party of three (Borchgrevink, Lt. Colbeck and a Finn called Savio) then undertook the first sledging journey on the barrier surface, and on 16 February 1900 took Farthest South to 78°50’. [21]

Robert Falcon Scott

The Discovery Expedition of 1901–04 was Captain Scott's first Antarctic command. Among the many features of the expedition was a long southern journey over the Barrier surface, undertaken by Scott, Edward Wilson and Ernest Shackleton, the object of which was, according to Wilson, to “reach the Pole if possible, or find some new land”. [22] The party set out on 1 November 1902 and by 11th had passed Borchgrevink's record.[23] The march continued, under increasing difficulties through lack of travelling experience and adverse weather, until 30 December, when Wilson and Scott took a short ski trip beyond their southern camp, to set a new Farthest South at (according to their measurements) 82°17’S.[24] This may not be exact; modern maps, correlated with Shackleton's photograph and Wilson's drawing, put their final camp at 82°6’S, and the point reached by Scott and Wilson at 82°11’S.[25] Whatever the precise latitude, they had extended Borchgrevink's mark by approximately 240 miles (400 km).

Ernest Shackleton

In command of his own Nimrod Expedition in 1907–09, Ernest Shackleton and three companions made a determined march for the South Pole. On 26 November 1908 Scott's furthest point was passed.[26] Thereafter the party continued southward, discovering and ascending the Beardmore Glacier to the polar plateau,[27] and then marching on to their Farthest South at 88°23’S, a mere 97 geographical miles (114 statute miles, 190 km) from the Pole. Shortages of food and supplies required them to turn north from this point, on 9 January 1909. [28]

The increase of more than six degrees south from Scott's previous record was easily the greatest extension of Farthest South since Captain Cook's 1773 mark. The record was to stand for a shorter time than any previous mark bar Borchgrevink's[29].

90 degrees south

Roald Amundsen's South Polar party set out from its base camp on the Ross Ice Shelf on 20 October 1911. It ascended the Transantarctic Mountains via the Axel Heiberg Glacier, passed Shackleton's Farthest South on 7 December 1911 and proceeded to the South Pole, attaining 90°S on 15 December. [30] He had reached the ultimate Farthest South. 33 days later Captain Scott's five-man team reached the same point. Of the six expeditions that held the Furthest South record prior to Amundsen's conquest of the Pole, five were British and the sixth, led by a Norwegian, was nominally British. However, the final triumph indisputably belonged to the Norwegians.

See also

Notes and references

- ^ See Wilson, p. 214, Riffenbaugh, p. 24, and Scott’ diary entry for 9 January 1912 (SLE Vol I p. 536) for typical expressions of triumph as a new Farthest South record was attained

- ^ The Norwegian Carsten Borchgrevink held the record between January 1900 and 11 November 1902. He was, however, commanding what was technically a British expedition.

- ^ Huntford, p. 20

- ^ Cook's record lasted 49 years, Weddell's 19 years and Ross's 48 years before things speeded up in the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

- ^ a b c d Magellan on-line biography

- ^ Magellan on-line biography See also The Fuegians and Patagonian People, http://www.andaman.org/BOOK/chapter54/text-Fuego/text-Fuego/htm#sites

- ^ George Weber: Europe discovers Tierra del Fuego, on-line on http://www.andaman.org/BOOK/chapter54/text-Fuego/text-Fuego.htm#sites

- ^ Synopsis of Drake's circumnavigation, on-line on http://www.mcn.org/2/oseeler/voy.htm

- ^ On-line, http://www.mundoandino.com/Chile/Diego-Ramirez-Islands

- ^ Coleman, p. 53–54

- ^ Coleman, p. 56

- ^ a b Coleman, p. 59

- ^ Coleman, p. 61

- ^ Preston, p. 11

- ^ a b c Weddell on-line biography

- ^ Coleman, p. 326

- ^ Coleman, p. 329

- ^ Coleman, p. 330

- ^ Coleman, p. 335

- ^ The expedition was financed by British publishing magnate Sir George Newnes. Despite the shortage of British participants Newnes insisted it be styled the “British Antarctic Expedition” – Preston, p. 4

- ^ Preston, pp. 13–15

- ^ Wilson diary, 12 June 1902, p. 151

- ^ Wilson diary, p. 214

- ^ Wilson diary, p. 230. Borchgrevink's mark was first passed by a depot-laying support team, led by Michael Barne.

- ^ Crane, pp. 214–15

- ^ Riffenburgh, p. 204

- ^ Riffenburgh, p. 227

- ^ Riffenburgh, pp. 231–33

- ^ It stood for 2 years 333 days. Borchgrevink's record had lasted 2 years 316 days

- ^ Amundsen, pp 120–30

Sources

- Amundsen, Roald: The South Pole C Hurst & Co (Publishers) Ltd 1976, ISBN 0 903983 47 8

- Coleman, E. C.: The Royal Navy in Polar Exploration from Frobisher to Ross Tempus Publishing 2006, ISBN 0 7524 3660 0

- Crane, David: Scott of the Antarctic Harper Collins 2005 ISBN 0 00 715068 7

- Preston, Diana: A First Rate Tragedy Constable Paperback 1999, ISBN 0 09 4795304

- Riffenburgh, Beau: Nimrod Bloomsbury Publishing Paperback 2005, ISBN 0 7475 7253 4

- Scott's Last Expedition, Vol I Smith, Elder & Co. 1913

- Wilson, Edward: Diary of the Discovery Expedition to the Antarctic, 1901–04 Blandford Press 1966, ISBN 0 7137 0431 4

- Magellan on-line biography Retrieved 10 March 2008

- Europe discovers Tierra Del Fuego, and The Fuegian and Patagonian People Retrieved 10 March 2008

- Weddell on-line biography Retrieved 10 March 2008