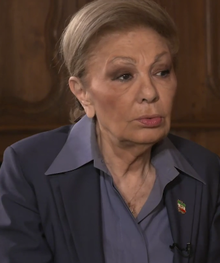

Farah Pahlavi

| Farah Pahlavi فرح پهلوی | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 1973 | |

| Consort of the Shah of Iran | |

| As queen | 21 December 1959 – 26 October 1967 |

| As empress (shahbanu) | 26 October 1967[1] – 11 February 1979 |

| Coronation | 26 October 1967 |

| Born | Farah Diba 14 October 1938 Tehran, Imperial State of Iran[2] |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | |

| House | Pahlavi (by marriage) |

| Father | Sohrab Diba |

| Mother | Farideh Ghotbi |

| Signature |  Persian signature Latin signature |

Farah Pahlavi (Persian: فرح پهلوی; née Diba [دیبا]; born 14 October 1938) is the former Queen and last Empress (شهبانو, Shahbânu) of Iran and is the widow of the last Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

She was born into a prosperous Iranian family whose fortunes were diminished after her father's early death. While studying architecture in Paris, she was introduced to Mohammad Reza at the Iranian embassy, and they were married in December 1959. The Shah's first two marriages had not produced a son—necessary for royal succession—resulting in great rejoicing at the birth of Crown Prince Reza in October of the following year. As a philanthropist, she progressed Iranian civil society through many charities, and founded Iran's first American-style university, enabling more women to become students in the country. She also facilitated the buying-back of Iranian antiquities from museums abroad.

By 1978, growing anti-imperial unrest fueled by communism, socialism, and Islamism throughout Iran was showing clear signs of impending revolution, prompting Farah and the Shah to leave the country in January 1979 under the threat of a death sentence. For that reason, most countries were reluctant to harbour them, with Anwar Sadat's Egypt being an exception. Facing execution should he return, and in ill health, Mohammad Reza died in exile in July 1980. In widowhood, Farah has continued her charity work, dividing her time between Washington and Paris.

Childhood

[edit]

Farah Diba was born on 14 October 1938 in Tehran to an upper-class family.[3][4][5] She was the only child of Captain Sohrab Diba (1899–1948) and his wife, Farideh Ghotbi (1920–2000). In her memoir, Farah writes that her father's family were natives of Iranian Azerbaijan while her mother's family were of Gilak origin, from Lahijan on the Iranian coast of the Caspian Sea.[6]

In the late 19th century her grandfather had been a diplomat serving as the Persian Ambassador to the Romanov Court in St. Petersburg, Russia. Her own father was an officer in the Imperial Iranian Armed Forces and a graduate of the French Military Academy at St. Cyr.

Farah wrote in her memoir that she had a close bond with her father, and his unexpected death in 1948 deeply affected her.[6] The young family was in a difficult financial state. In their reduced circumstances, they were forced to move from their large family villa in northern Tehran into a shared apartment with one of Farideh Ghotbi's brothers.

Education and engagement

[edit]The young Farah Diba began her education at Tehran's Italian School, then moved to the French Jeanne d’Arc School until the age of sixteen and later to the Lycée Razi.[7] She was an athlete in her youth, becoming captain of her school's basketball team. Upon finishing her studies at the Lycée Razi, she pursued an interest in architecture at the École Spéciale d'Architecture in Paris,[8] where she was a student of Albert Besson.

Many Iranian students who were studying abroad at this time were dependent on State sponsorship. Therefore, when the Shah, as head of state, made official visits to foreign countries, he frequently met with a selection of local Iranian students. It was during such a meeting in 1959 at the Iranian Embassy in Paris that Farah Diba was first presented to Mohammed Reza Pahlavi.

After returning to Tehran in the summer of 1959, Mohammad Reza and Farah Diba began their courtship. The couple announced their engagement on 23 November 1959.

Marriage and family

[edit]

Farah Diba married Shah Mohammed Reza on 20 December 1959, aged 21. The young Queen of Iran (as she was styled at the time) was the object of much curiosity and her wedding received worldwide press attention. Her gown was designed by Yves Saint Laurent, then a designer at the house of Dior, and she wore the newly commissioned Noor-ol-Ain Diamond tiara.[9]

After the pomp and celebrations associated with the imperial wedding, the success of this union became contingent upon the queen's ability to produce a male heir. Although he had been married twice before, the Shah's previous marriages had given him only a daughter who, under agnatic primogeniture, could not inherit the throne. The pressure for Farah was acute. The shah himself was deeply anxious to have a male heir as were the members of his government.[10] Furthermore, it was known that the dissolution of the Mohammad Reza's previous marriage to Queen Soraya had been due to her infertility.[11]

The couple had four children:

- Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi of Iran (born 31 October 1960). He and his wife Yasmine have three daughters.

- Princess Noor Pahlavi (born 3 April 1992)

- Princess Iman Pahlavi (born 12 September 1993)

- Princess Farah Pahlavi (born 17 January 2004)

- Princess Farahnaz Pahlavi of Iran (born 12 March 1963)

- Prince Ali Reza Pahlavi of Iran (28 April 1966 – 4 January 2011). He and his companion Raha Didevar had one daughter.[12]

- Iryana Leila Pahlavi (born 26 July 2011)

- Princess Leila Pahlavi of Iran (27 March 1970 – 10 June 2001)

As queen and empress

[edit]The exact role the new queen would play, in public or government affairs, was uncertain with her main role being simply to give the Shah a male heir.[13] Within the Imperial Household, her public function was secondary to the far more pressing matter of assuring the succession. However, after the birth of the Crown Prince, the Queen was free to devote more of her time to other activities and official pursuits.

Like many other royal consorts, Farah initially limited herself to a ceremonial role. In 1961 during a visit to France, the Francophile Farah befriended the French culture minister André Malraux, leading her to arrange the exchange of cultural artifacts between French and Iranian art galleries and museums, a lively trade that continued until the Islamic revolution of 1979.[14] She spent much of her time attending the openings of various education and health-care institutions without venturing too deeply into controversial issues. However, as time progressed, this position changed. The Queen became much more actively involved in government affairs where it concerned issues and causes that interested her. She used her proximity and influence with her husband Mohammad Reza, to secure funding and focus attention on causes, particularly in the areas of women's rights and cultural development.[13] Farah's concerns were the "realms of education, health, culture and social matters" with politics being excluded from her purview.[13]

One of Farah's main initiatives was founding Pahlavi University (now Shiraz University), which was meant to improve the education of Iranian women, and was the first American-style university in Iran; before then, Iranian universities had always been modeled on the French style.[13] The Empress wrote in 1978 that her duties were:

I could not write in detail of all the organizations over which I preside and in which I take a very active part, in the realms of education, health, culture and social matters. It would need a further book. A simple list would perhaps give some idea: the Organization for Family Well Being-nurseries for the children of working mothers, teaching women and girls to read, professional training, family planning; the Organization for Blood Transfusion; the Organization for the Fight Against Cancer; the Organization for Help to the Needy, the Health Organization ... the Children's Centre; the Centre for the Intellectual Development of Children ... the Imperial Institute of Philosophy; the Foundation for Iranian Culture; the Festival of Shiraz, the Tehran Cinema Festival; the Iranian Folklore Organization; the Asiatic Institute; the Civilisations Discussion Centre; the Pahlavi University; the Academy of Sciences.[13]

Farah worked long hours at her charitable activities, from about 9 am to 9 pm every weekday.[13] Eventually, the Queen came to preside over a staff of 40 who handled various requests for assistance on a range of issues. She became one of the most highly visible figures in the Imperial Government and the patron of 24 educational, health and cultural organizations.[13] Her humanitarian role earned her immense popularity for a time, particularly in the early 1970s.[15] During this period, she travelled a great deal within Iran, visiting some of the more remote parts of the country and meeting with the local citizens.

Farah's significance was exemplified by her part in the 1967 Coronation Ceremonies, where she was crowned as the first shahbanu (empress) of modern Iran. It was again confirmed when the Shah named her as the official regent should he die or be incapacitated before the Crown Prince's 21st birthday. The naming of a woman as regent was highly unusual for a Middle Eastern or Muslim monarchy.[15] The great wealth generated by Iran's oil encouraged a sense of Iranian nationalism at the Imperial Court. The Empress recalled of her days as a university student in 1950s France about being asked where she was from:

When I told them Iran ... the Europeans would recoil in horror as if Iranians were barbarians and loathsome. But after Iran became wealthy under the Shah in the 1970s, Iranians were courted everywhere. Yes, Your Majesty. Of course, Your Majesty. If you please, Your Majesty. Fawning all over us. Greedy sycophants. Then they loved Iranians.[16]

Contributions to art and culture

[edit]

From the beginning of her royal life, Farah took an active interest in promoting culture and the arts in Iran. Through her patronage, numerous organizations were created and fostered to further her ambition of bringing historical and contemporary Iranian Art to prominence both inside Iran and in the Western world.

In addition to her own efforts, Farah sought to achieve this goal with the assistance of various foundations and advisers. Her ministry encouraged many forms of artistic expression, including traditional Iranian arts (such as weaving, singing, and poetry recital) as well as Western theatre. Her most recognized endeavour supporting the performing arts was her patronage of the Shiraz Arts Festival. This occasionally controversial event was held annually from 1967 until 1977 and featured live performances by both Iranian and Western artists.[17]

The majority of her time, however, went into the creation of museums and the building of their collections.

As a former architecture student, Farah's appreciation of it is demonstrated in the Royal Palace of Niavaran, designed by Mohsen Foroughi, and completed in 1968: it mixes traditional Iranian architecture with 1960's contemporary design. Nearby is the personal library of the Empress, consisting of 22,000 books, comprising principally works on Western and Eastern art, philosophy and religion; the interior was designed by Aziz Farmanfarmayan.

Ancient art

[edit]Historically a culturally rich country, the Iran of the 1960s had little to show for it. Many of the great artistic treasures produced during its 2,500-year history had found their way into the hands of foreign museums and private collections. It became one of Farah's principal goals to procure for Iran an appropriate collection of its own historic artifacts. To that end, she secured from her husband's government permission and funds to "buy back" a wide selection of Iranian artifacts from foreign and domestic collections. This was achieved with the help of the brothers Houshang and Mehdi Mahboubian, the most prominent Iranian antiquities dealers of the era, who advised the Empress from 1972 to 1978.[18] With these artifacts she founded several national museums (many of which still survive to this day) and began an Iranian version of the National Trust.[19]

Museums and cultural centres created under her guidance include the Negarestan Cultural Center, the Reza Abbasi Museum, the Khorramabad Museum with its valuable collection of Lorestān bronzes, the National Carpet Gallery and the Glassware and Ceramic Museum of Iran.[20]

Contemporary art

[edit]

Aside from building a collection of historic Iranian artifacts, Farah also expressed interest in acquiring contemporary Western and Iranian art. To this end, she put her significant patronage behind the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art.

Using funds allocated from the government, the Shahbanu took advantage of a somewhat depressed art market of the 1970s to purchase several important works of Western art. Under her guidance,[citation needed] the museum acquired nearly 150 works by such artists as Pablo Picasso, Claude Monet, George Grosz, Andy Warhol, Jackson Pollock, and Roy Lichtenstein. The collection of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art is considered to be one of the most significant outside Europe and the United States. The vast collection has been tastefully showcased in a large coffee table book published by Assouline titled Iran Modern[21] According to Parviz Tanavoli, a modern Iranian sculptor and a former Cultural Adviser to the Empress, that the impressive collection was amassed for "tens, not hundreds, of millions of dollars".[19] As of 2008[update], the value of these holdings are conservatively estimated to be near US$2.8 billion.[22]

The collection created a conundrum for the anti-western Islamic Republic which took power after the fall of the Pahlavi Dynasty in 1979. Although politically the fundamentalist government rejected Western influence in Iran, the Western art collection amassed by Farah was retained, most likely due to its enormous value. It was, nevertheless, not publicly displayed and spent nearly two decades in storage in the vaults of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art. This caused much speculation as to the fate of the artwork which was only put to rest after a large portion of the collection was briefly seen again in an exhibition that took place in Tehran during September 2005.[22]

Islamic Revolution

[edit]

By early 1978, dissatisfaction with Iran's imperial government was pronounced. By the end of the year, citizens were holding demonstrations against the monarchy.[23] Pahlavi wrote in her memoirs that "there was an increasingly palpable sense of unease". Under these circumstances most of the Shahbanu's official activities were cancelled due to concerns for her safety.[10]

Riots and unrest grew more frequent and culminated in January 1979. The government enacted martial law in most major Iranian cities and the country was on the verge of an open revolution. Mohammad Reza and Farah departed Iran via aircraft on 16 January 1979.

After leaving Iran

[edit]

For more than a year, the couple searched for permanent asylum. Many governments were unwilling to allow them within their borders because the revolutionary government in Iran had ordered the Shah and Shahbanu's arrest and death and it was not known how much it would pressure foreign powers.

Egyptian president Anwar Sadat, who had maintained close relations with Mohammad Reza for years (and whose wife Jehan Sadat was friends with Farah), allowed them to stay in Egypt. They also spent time in Morocco, where they were guests of King Hassan II, and in the Bahamas. When their Bahamian visas were not renewed, they went to Mexico and rented a villa in Cuernavaca near Mexico City during the summer of 1979.

Shah's illness

[edit]After leaving Egypt, Mohammad Reza's health further declined from non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. In October 1979, the couple was allowed into the United States for medical treatment, inflaming already tense relations between the US government and the revolutionaries in Tehran. The tensions ultimately led to the attack and takeover of the American embassy in Tehran in what became known as the Iran hostage crisis. The Shah and Shahbanu were not permitted to remain in the United States, and shortly after the Shah's surgical treatment on 22 October 1979, the couple departed for Contadora Island in Panama. Both Mohammad Reza and Farah viewed the Carter administration with some antipathy in response to a lack of support.

Speculation arose that the Panamanian government was seeking to arrest Mohammad Reza in preparation for extradition to Iran.[24] The Shah and Shahbanu again made an appeal to President Anwar Sadat to return to Egypt (Empress Farah writes that this plea was made through a conversation between herself and Jehan Sadat). Their request was granted and they returned to Egypt in March 1980, where they remained until the Shah's death four months later on 27 July 1980.

Life in exile

[edit]

After the Shah's death, Farah spent two years in Egypt, where President Anwar Sadat allowed her and the children to stay in the Koubbeh Palace. She was the regent in pretence from 27 July to 31 October 1980.[25] A few months after President Sadat's assassination in October 1981, Farah and her family left Egypt. President Ronald Reagan informed her that she was welcome in the United States.[26]

Farah first settled in Williamstown, Massachusetts and later bought a home in Greenwich, Connecticut. After the death of her daughter Princess Leila in 2001, she purchased a smaller home in Potomac, Maryland, near Washington, D.C. to be closer to her son and grandchildren. Farah divides her time between Washington, D.C. and Paris and makes an annual July visit to Mohammad Reza Shah's mausoleum at Cairo's al-Rifa'i Mosque.

Farah attended the funeral of former U.S. president Ronald Reagan in Washington, D.C. She supports charities, including the International Fund Raising for Alzheimer Disease gala in Paris.[27]

Farah continues to appear at certain international royal events such as the 2004 wedding of Crown Prince Frederik of Denmark, the 2010 wedding of Prince Nikolaos of Greece and Denmark, the 2011 wedding of Albert II, Prince of Monaco, the 2016 wedding of Prince Leka of Albania, the 2023 funeral of Constantine II of Greece, and the 2023 wedding of Crown Prince Hussein of Jordan.

Memoir

[edit]In 2003, Farah wrote a book about her marriage to Mohammad Reza entitled An Enduring Love: My Life with the Shah. The publication of the former Empress's memoirs attracted international interest. It was a best-seller in Europe, with excerpts appearing in news magazines and the author appearing on talk shows and in other media outlets. However, opinion about the book, which Publishers Weekly called "a candid, straightforward account" and The Washington Post called "engrossing", was mixed.[citation needed]

Elaine Sciolino, The New York Times's Paris bureau chief, gave the book a less than flattering review, describing it as "well translated" but "full of anger and bitterness".[28] But National Review's Reza Bayegan, an Iranian writer, praised the memoir as "abound[ing] with affection and sympathy for her countrymen."[29]

Documentaries and theatre play

[edit]In 2009 the Persian-Swedish director Nahid Persson Sarvestani released a feature length documentary about Farah Pahlavi's life, entitled The Queen and I. The film was screened in various International film festivals such as IDFA and Sundance.[30] In 2012 the Dutch director Kees Roorda made a theatre play inspired by the life of Farah Pahlavi in exile. In the play Liz Snoijink acted as Farah Diba.[31]

Honours

[edit]| Styles of Empress Farah of Iran | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | Her Imperial Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Imperial Majesty |

|

|

National

[edit] Member 1st Class of the Order of the Pleiades[32]

Member 1st Class of the Order of the Pleiades[32]

Foreign

[edit] Austria: Grand Star of the Decoration of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria[33]

Austria: Grand Star of the Decoration of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria[33] Czechoslovakia: Grand Cross of the Order of the White Lion[34]

Czechoslovakia: Grand Cross of the Order of the White Lion[34] Denmark: Order of the Elephant[35]

Denmark: Order of the Elephant[35] Italy: Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic[36]

Italy: Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic[36] Norway: Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Olav

Norway: Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Olav Spain: Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic[37]

Spain: Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic[37] Thailand: Dame of the Most Illustrious Order of the Royal House of Chakri[38]

Thailand: Dame of the Most Illustrious Order of the Royal House of Chakri[38]

Awards

[edit] Austria: Look! Women of the Year Hope Award[39]

Austria: Look! Women of the Year Hope Award[39] France: Foreign Associate Academician of the Académie des Beaux-Arts[40]

France: Foreign Associate Academician of the Académie des Beaux-Arts[40] Germany: Steiger Award[41]

Germany: Steiger Award[41] Germany: Südwestfalen Charlie Award[42]

Germany: Südwestfalen Charlie Award[42] United States: National Museum of Women in the Arts Award for International Cultural Patronage[43]

United States: National Museum of Women in the Arts Award for International Cultural Patronage[43]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Queen Farah Pahlavi". farahpahlavi.org. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ Afkhami, Gholam Reza (12 January 2009). The Life and Times of the Shah. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520942165.

- ^ Afkhami, Gholam Reza (12 January 2009). The life and times of the Shah (1 ed.). University of California Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-520-25328-5.

- ^ Shakibi, Zhand (2007). Revolutions and the Collapse of Monarchy: Human Agency and the Making of Revolution in France, Russia, and Iran. I.B. Tauris. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-84511-292-9.

- ^ Taheri, Amir. The Unknown Life of the Shah. Hutchinson, 1991. ISBN 0-09-174860-7; p. 160

- ^ a b Pahlavi, Farah. 'An Enduring Love: My life with The Shah. A Memoir' 2004

- ^ "Empress Farah Pahlavi Official Site - سایت رسمی شهبانو فرح پهلوی". farahpahlavi.org. Archived from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ^ Meng, J. I. (29 July 2013). Translation, History and Arts: New Horizons in Asian Interdisciplinary Humanities Research. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 9781443851176.

- ^ Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (17 March 2015). World Clothing and Fashion: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Social Influence. Routledge. ISBN 9781317451679.

- ^ a b Pahlavi, Farah. 'An Enduring Love: My Life with The Shah. A Memoir', 2004.

- ^ "Queen of Iran Accepts Divorce As Sacrifice", The New York Times, 15 March 1958, p. 4.

- ^ "Announcement of Birth". Reza Pahlavi. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zonis, Marvin Majestic Failure The Fall of the Shah, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991 page 138.

- ^ Milani, Abbas The Shah, London: Macmillan, 2011 page 279

- ^ a b "The World: Farah: The Working Empress". Time. 4 November 1974. Archived from the original on 3 July 2009.

- ^ Zonis, Marvin Majestic Failure The Fall of the Shah, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991 page 221.

- ^ Gluck, Robert (2007). "The Shiraz Arts Festival: Western Avant-Garde Arts in 1970s Iran". Leonardo. 40: 20–28. doi:10.1162/leon.2007.40.1.20. S2CID 57561105.

- ^ Norman, Geraldine (13 December 1992). "Mysterious gifts from the East". The Independent. London.

- ^ a b de Bellaigue, Christopher (7 October 2005). "Lifting the veil". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Pahlavi, Farah. "An Enduring Love: My Life with The Shah. A Memoir" 2004

- ^ Raikhel-Bolot, Viola; Darling, Miranda (2018). Iran Modern. New York, USA: Assouline. p. 200.

- ^ a b "Iran: We Will Put American Art Treasures on Display". ABC News. 7 March 2008.

- ^ "1978: Iran's PM steps down amid riots". BBC News. 5 November 1978.

- ^ "The Shah's Flight". Time. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011.

- ^ "Former Iranian Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi will proclaim himself the new shah of Iran", United Press International, 17 October 1980,

His Imperial Highness Reza Pahlavi, Crown Prince of Iran, will reach his constitutional majority on the 9th of Aban, 1359 (31 October 1980). On this date, and in conformity with the Iranian Constitution, the regency of Her Imperial Majesty Farah Pahlavi, Shahbanou of Iran, will come to an end and His Imperial Highness, who on this occasion will send a message to the people of Iran, will succeed his father, His Imperial Majesty Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi, deceased in Cairo on Mordad 5, 1359 (27 July 1980).

- ^ Pahlavi, Farah. "An Enduring Love: My life with Shah. A Memoir" 2004

- ^ "Enduring Friendship: Alain Delon and Shahbanou Farah Pahlavi at annual Alzheimer Gala in Paris". Payvand. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ Sciolino, Elaine (2 May 2004). "The Last Empress". The New York Times.

- ^ Bayegan, Reza (13 May 2004). "The Shah & She". National Review.

- ^ "The Queen and I". sundance.org.

- ^ "Farah Diba, World's Prettiest Woman: Premiere in Haarlem". iranian.com. 2012. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ "The Shah of Iran Marries Farah Diba". Getty Images. 1 December 1959. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "Reply to a parliamentary question" (PDF) (in German). p. 193. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ "Kolana Řádu Bílého lva aneb hlavy států v řetězech". Vyznamenani.net. 25 June 2010. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ "Modtagere af danske dekorationer". Kongehuset (in Danish). Retrieved 20 April 2024.

- ^ "FARAH PAHLAVI S.M.I. decorato di Gran Cordone" (in Italian). Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ "III. Otras disposicionel" (PDF). Boletín Oficial del Estado (in Spanish). 13 November 1969. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ Royal Thai Government Gazette (28 December 1960). "แจ้งความสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี เรื่อง พระราชทานเครื่องราชอิสริยาภรณ์" (thajsky) Dostupné online

- ^ [1] Archived 26 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Farah Pahlavi Official Site". Farahpahlavi.org. Archived from the original on 11 July 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ "Farah Pahlavi Official Site". Farahpahlavi.org. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ "Farah Pahlavi Official Site". Farahpahlavi.org. Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ "Farah Pahlavi Official Site". Farahpahlavi.org. 25 April 2014. Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]External links

[edit]- 20th-century Iranian women

- 21st-century Iranian women

- 1938 births

- Living people

- Wives of Pahlavi Shahs

- People of the Iranian revolution

- Recipients of the Grand Star of the Decoration for Services to the Republic of Austria

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the White Lion

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic

- Dames Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic

- Iranian Azerbaijanis

- Muslim reformers

- Queens consort of Persia

- Royalty from Tehran

- 20th-century Iranian artists

- Iranian architects

- Iranian women architects

- Iranian women artists

- Iranian emigrants to France

- Iranian emigrants to the United States

- Exiles of the Iranian revolution in the United States

- Exiles of the Iranian revolution in Egypt

- Exiles of the Iranian revolution in Morocco

- Exiles of the Iranian revolution in the Bahamas

- Exiles of the Iranian revolution in Mexico

- Exiles of the Iranian revolution in Panama

- People from Potomac, Maryland

- École Spéciale d'Architecture alumni

- Iranian memoirists

- Exiled royalty

- Iranian women's rights activists

- Iranian monarchists